1. Literature Review of the Impact Flooding Has on Agricultural Land

Globally, annual flooding affects a significant amount of land mass, which results in severe damage to agricultural plants and crop yield losses (Voesenek & Sasidharan, 2013). It has been estimated that between 10 – 12% of the land used for agriculture globally is affected by waterlogging resulting in severe problems with soil drainage (Shabala, 2011, Kaur et al., 2019). In the United States for example, flooding is considered a severe danger and has been ranked second after drought among abiotic stresses contributing to crop production losses from 2000 to 2011 (Bailey-Serres et al., 2012). It has also been estimated that about 16% of soils in the United States are affected by water flooding (Manik et al., 2019).

According to a report published recently by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), approximately USD

$21 billion was lost in agricultural production worldwide because of floods between the years 2008 to 2018.

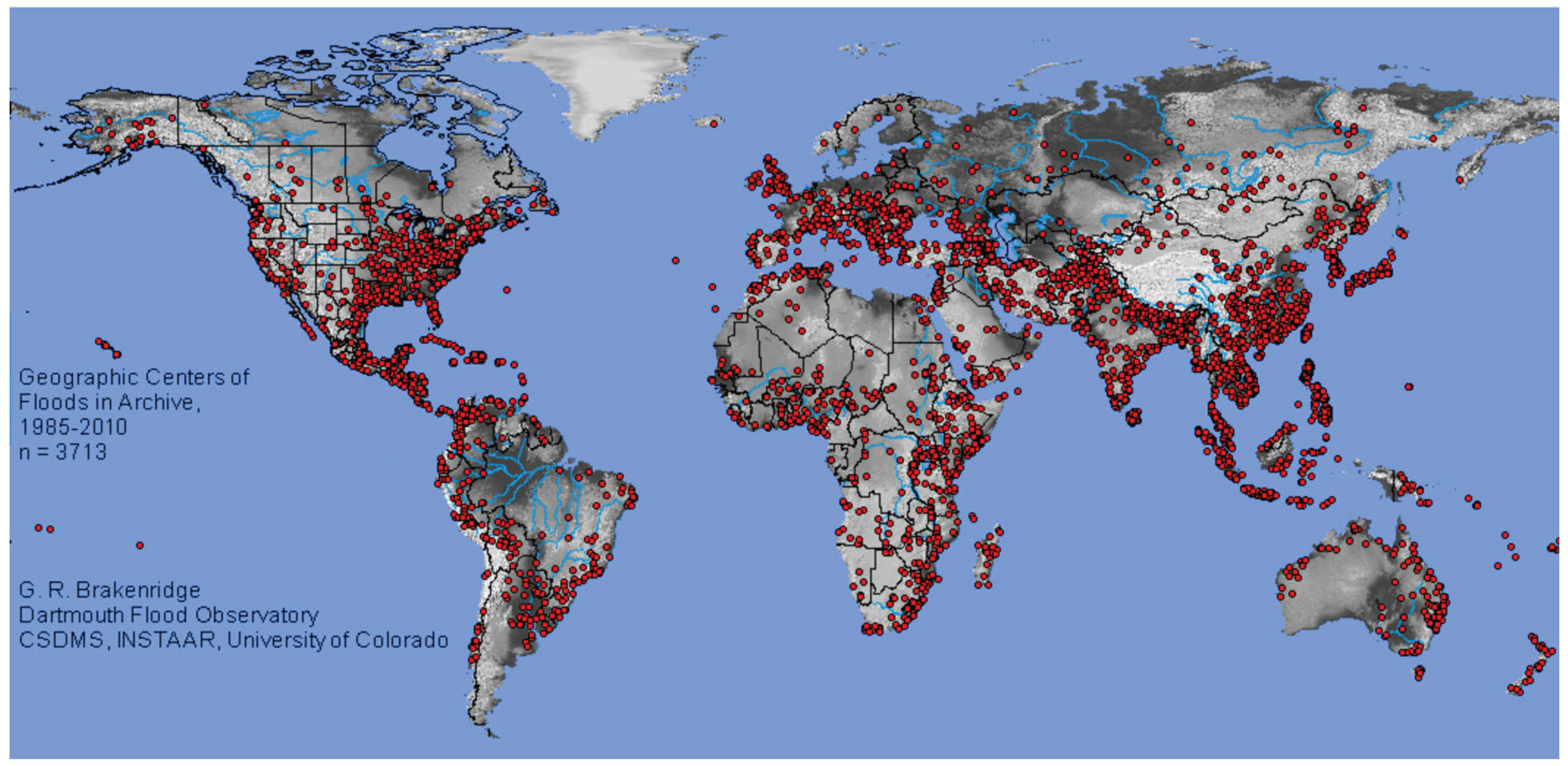

Figure 1 shows the locations of all recorded floods taken place from 1985 to 2010 on the planet (

http://floodobservatory.colorado.edu). In the United States, excessive flooding has been reported to have caused losses of well over

$1.5 billion dollars in terms of corn and soybean productivity losses in the Upper Midwestern states in 2011 (Bailey-Serres et al., 2012). Another example of flood damage includes the 1993 floods in the Midwestern region of the United States, where over 10 million acres of agricultural crops were damaged. It was estimated that about 50% of the total grain yield losses were due to crop damage as a result of flooding, losses which was valued at between

$6 and 8 billion (Rosenzweig et al., 2001; Rosenzweig et al., 2002). Off course that the time of flooding can have a significant impact on the amount of damage caused, but this needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. For example, a moderate flooding happening in July causing 35% reduction in yield loss would be less severe than a flooding that took place in April/May and prevented a crop from being planted and the land was left fallow. Off course a severe flooding accompanied by hail in the middle of the season could also cause total loss of a crop or loss of stored grain. For example, the 2019 flooding of Midwestern States including Iowa, Nebraska, Missouri, and North Dakota resulted in loss of tens of millions of dollars by multiple failures. In some farms, waterlogging prevented planting of crops past insurance deadline; in others planted acres were lost as the plant roots ran out of oxygen; and even stored corn from the previous season was lost. Increased precipitation and the potential for increased flooding frequency is expected to happen worldwide as a result of global climate change, with major consequences to be expected in floodplains and also in areas which are prone to flooding.

Soil structure can be adversely affected by flooding, and as a result it can adversely impact all properties and functions of soil, physical, chemical, and biological. Clay soils are the type of soils that are most likely to suffer from decreases in structure when flooding happens (Alaoui et al., 2018). Soil structure is controlled by aggregate formation and aggregate stability. Soil aggregation is interconnected with the soil structure because soil aggregation is formed by the binding of soil particles through soil organic matter (SOM) to form secondary units (Runpgam and Messiga, 2024). These two soil properties are very important determinants of soil health and overall agricultural productivity of soils. Resistance to slacking is a key indicator for how well soil structure and aggregation is. Slacking occurs when soil aggregates are not strong enough to withstand the internal pressures that takes place when there is rapid water uptake in a soil. Therefore, flooding impacts soil structure and aggregation by causing slacking in poorly structured soil. The repeated inundation and exposure to air associated with flooding are intensive disturbance factors for soil structure and aggregation. Aggregates are also the foundation for the soil porosity, which are channels in the soil where microbial and plant life thrive.

There are two types of soil porosity, structural and textural porosity. Structural porosity are the pores formed by aggregates and are responsible for water and nutrient movement. The quality and stability of the aggregate will dictate many processes that take place in the soil, which are directly connected to crop productivity. A soil with strong aggregate stability and good porosity will provide the best environment for crops to yield their maximum. Textural porosity is the porosity resulting from the spaces between particle of different sizes, and the smaller the particle size the smaller the pore sizes. Textural pores are also very active with interactions between microbial and plant life, however, in some cases the chemical and biological conditions change significantly. Depending on the amount of sand, silt, and clay in the soil, different porosity with different bulk density will develop naturally and will give a given soil a certain type of structure. For example, soils formed from Glacial till such as the Fargo soil is known for having dense and poorly drained subsurface horizons due to the distribution of sand, silt, and clay during glacier deposition. The textural porosity in this case dominates and little structural porosity is present in the subsurface of those soils. The balance between textural and structural porosity determines the types and ratios of pores that are present in a soil.

Pores which are connected from the surface to the lower layers are called drainage pores, while disconnected pores are called storage pores. Storage pores do not have a way for water to escape and could potentially become anaerobic when the soil is water saturated for prolonged time. Aggregate stability is closely related to structural porosity and the greater number of aggregates and the stronger they are, the better the structural porosity will be. When soil aggregates stability is lost due to the internal pressure caused by flooding, significant impact on water movement can happen and drainage pores can collapse into storage pores. Clay soils with their fine particles and high-water retention capacity create dense, sticky conditions when saturated that can reduce pore space and lead to a significant rearrangement of small particles when under significant pressure leading to changes in density, or compacting the soil (Kodikara et al., 2018). Sandy soils, with larger particles and better drainage, are less prone to compaction, while loamy soils fall in between but are less affected than clay soils. Soil compaction depending on severity can have significant influence on plant growth, soil microbial life, and nutrient cycling (Batey, 2009).

The breakdown of aggregates due to flooding can cause disruption of drainage pores increasing the time needed for water to drain through the soil profile. Depending on soil particle rearrangement as aggregate collapse, increases in bulk density can be observed. Denser soils offer higher resistivity for roots to grow and develop well. Root growth is responsible for water and nutrient acquisition, and the easier they can grow in a soil the more likely plants will be to produce their maximum.

Waterlogging can also have significant influences on soil biogeochemical processes as well. When flooding takes place, the soil will be depleted from oxygen which creates anaerobic conditions thereby affecting microbial metabolism and the as a result interfering with the biogeochemical cycling of nutrients (Rupngam and Messiga, 2024). Flooding events impact on soil properties varies and depends on many factors including intensity and duration of the flooding event, and soil type (texture, total porosity, structure, aggregation level). Adaptive soil management practices and flood mitigation strategies to enhance soil resilience and ecosystem sustainability in flood-prone regions are needed to help alleviate the negative effects of flooding in agricultural regions. Flooding can also cause nutrient losses on a predictable pattern:

- -

Nitrogen losses can happen due to denitrification and nitrate leaching, causing increases in greenhouse gas emission, and, in the amount of nitrate in flowing water. Increased nitrate in leaching water can potentially degrade ground water quality, and excessive nitrate leaching will also have a significant impact on aquatic ecosystems.

- -

Soluble phosphorus can be lost via runoff and by being dissolved in the flooding water and leaching away as the flooding water recedes or infiltrates the soil. Increased P in receding waters and runoff can potentially increasing algal bloom in freshwater systems.

- -

Other nutrients that are water soluble such as potassium and sulfur can also be lost from the system as the flooding water recedes, or in the case of sulfur be lost due to sulfur reduction in redox reactions in saturated soils.

- -

Flooding can also cause change in microbial mediated reactions that can have a significant impact on a soil’s productivity status.

Nutrient losses due to waterlogging and flooding can lead to reduced nutrient uptake by plants, which can also interfere with nutrient use efficiency and ultimately negatively impact surface and groundwater quality (Rupngam and Messiga, 2024). Therefore, it is important to understand how the duration of the flood and the volume of water present in the event can impact a soil and the effects on its productivity.

This report will provide a description on the potential impacts that flooding can have on the ability of soil to maintain its function. This report does not try to predict what will happen in each potential parcel of land but rather will describe the significance of flooding on the biological aspects of the soil ecosystem.

2. Flooding Frequency and Duration

Flooding frequency can be defined as the probability that a flood event of a given magnitude would take place in any given year. This characteristic is important when assessing flood risk and designing management plans to help with flood mitigation strategies. Flooding of agricultural land are occurring with greater frequency worldwide, which is a trend expected to continue due to climate change and the fact that the atmosphere can hold 7% more moisture for each 1oC increase in temperature (Li et al., 2024; WHO 2024). By analyzing historical flood records combined with hydrological modeling studies can offer a perceptive into the current and future variability and trends in flood occurrences. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that flood frequency should not be assumed to be stationary, which challenges the validity of using past flood patterns in the development water management designs to manage flooding (Myhre et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019).

Flood frequency of any given area can also be related to rainfall amount and catchment area characteristics. One method used to forecast flood frequency is the design storm method, which consists of estimating a hydrograph with a given peak discharge probability from a synthetic rainstorm with the same probability using a rainfall-runoff model (Pilgrim and Cordery, 1975). The rational formula is also used to forecast flood, this method transforms rainfall to flood frequency by estimating peak streamflow from critical rainfall intensities (Pilgrim and Cordery, 1975). The frequency of flooding can also be influenced by the volume of water present in the soil in the catchment area right before flooding starts (Slater and Villarini, 2016). The storage capacity of a catchment area that is already wet (for example had a large rainfall a couple days prior) is limited and tends to increase runoff events and potentially increase flood frequency. In contrast, in dry catchment areas (no rainfall for a significant amount of time e.g. 6 weeks+) infiltration is the dominant process and runoff events are mainly random and related to topography. The spatial distribution of rainfall water exceeding the storage capacity threshold of a soil plays a significant role in flood frequency (Zhu et al., 2018). Flooding will start when the volume of water being added is larger than the volume being drained per unit of time. Other research has shown that events which are high in volume and generate significant runoff, can be routing large volumes of water at once and impact flood frequency (Viglione and Blöschl, 2009).

Flooding duration is usually determined as the number of days that the soil remains submerged. The dry down time, the time the waterlogged soil takes to dry and reach field capacity in agricultural areas. The actual total amount of time flooding impact any agricultural soil is the addition of both duration of flooding and the dry down time. Soil texture and density plays an important role in how quick a soil will dry after a given flood duration as soils with a sandier texture will dry much faster than soils with a clay texture. Biogeochemical processes, such as organic matter turnover, nutrient cycling, like N and P, are altered in soil under inundation.

Agricultural lands are increasingly susceptible to increased frequency of flooding, especially in floodplains. These areas have been characterized as fertile and easy-to-cultivate soils, which makes farmers and farming comminutes vulnerable to floods. The biggest challenges farmers are faced with in flooded agricultural soil is the modification of soil properties, which can affect nutrient dynamics by changing soil properties and increasing nutrient loss (notably N and P) from soil to water sources. Nutrient loss poses economic risks for the farmer and also poses risks to water quality and eutrophication downstream.

3. Flooding Impacts on Soil Properties

3.1. How Flooding Can Impact Soil Structure and Aggregation

Soil structure is defined as the arrangement of soil particles into larger structures called aggregates which can be found in varying sizes and shapes. Soil structure is known to influence air, water, and nutrient flow, and is also involved in resistance to soil compaction and erosion and plays an important role in plant growth. Soil structure and aggregate stability are closely connected with soil health and agricultural productivity. Soil structure and aggregation can be determined by is its resistance to slaking. Slaking occurs when soil aggregates were poorly formed and are not strong enough to tolerate the stresses caused by rapid water uptake. The sporadic inundation of soils which causes saturation and drainage causing exposure to air are intensive disturbance factors for soil structure and aggregation. There are many different mechanisms which controls the stability of soil aggregates. In soils dominated by 2:1 clay mineral, the amount of organic matter present in the soil will play the main role as a binding agent; whereas in weathered soils where 1:1 clay mineral prevails, the amount of Fe and Al oxides will determine aggregate stability.

The size and duration of a flood event will control the amount of oxygen that is present in the soil and also will determine the extent of anaerobic conditions and ultimately will impact soil quality (Sîli et al., 2020). Lowered oxygen concentrations in the soil resulting from flooding events impacts organic matter dynamics and the redox reactions in the soil. The interation of organic matter and soil particles are the processes that controls the binding agents responsible for soil structure and aggregation. Prolonged inundation caused by flooding and waterlogging promote soil clay dispersion, will lead to reductions in soil pore space and ultimately leading to impaired soil structure. The disruption of soil aggregates and the impediment of soil aggregate formation because of flooding may lead to increased erosion and sediment transport of soil particles during flooding events. Increased soil particles leaving a field can contribute to sedimentation in water bodies and the degradation of aquatic ecosystems; it can also disrupt established drainage pores.

3.2. Impact of Flooding on Soil Water-Holding Capacity and Soil Porosity

Soil porosity is the amount of air space that is present between soil particles, or it is the fraction of the total soil volume that is occupied by space. Soil porosity controls the movement and also the availability of water and air within the soil environment. Research has shown that after two years of seasonal flooding, textural porosity increased at the expense of structural porosity and a percentage of drainage pores collapsed into storage pores (Kostopoulou et al., 2015). This means that the bulk density of the soil can increase leading to a reduction in the number of pores that are beneficial to productivity, increase the soil resistance to root growth, and decrease soil available water. In contrast, other studies reported that a reduction in total porosity is typical of flooding (Rahman et al., 2008). Flooding affects soil porosity differently with depth and in the topsoil, flooding reduces macroporosity, while for subsurface layers flooding decreases drainage pores (Aschonitis et al., 2012; Kostopoulou et al., 2015). For subsurface layers, the soil is supplied with organic compounds (roots exudates, dead plant matter, and microbial waste) that stabilize the structure and create macropores that are resistant to the slaking induced by flooding (Cameira et al., 2003). Flooding events depending on size and duration can also alter soil water holding capacity, manipulating soil water dynamics, and also impact nutrient cycling and nutrient availability. In addition, the saturated conditions during flooding will reduce air-filled pore space, which limits oxygen diffusion and as a result limits the amount of oxygen available for root growth. The diffusion of oxygen in water is more than 10,000 times slower than the diffusion of oxygen in air. For example, after long periods of flooding, e.g. 24 h, soil oxygen concentrations are reduced and anaerobic conditions begin to prevail when the oxygen concentration in the soil drops below 1% (Banach et al., 2009). Pore clogging and soil compaction further restrict water infiltration and drainage, exacerbating waterlogging and anaerobic conditions in flooded soils. In summary, changes in soil porosity and water-holding capacity affect nutrient availability, plant water uptake, and as result they will have a combined negative effect on soil fertility and crop productivity and yield.

3.3. Flooding Effects on Soil Texture

Every soil is composed of a mixture of particles with different sizes, such as sand, silt, and clay, and their arrangement determines the texture of each soil. Soil texture is a stable soil property that takes thousands of years to millennia to change, and this property has a strong influence on soil biophysical properties. When flooding takes place the deposition of sediments with running water as the area drains can induce changes in soil texture as particles of different sizes move along with the draining water. Low-lying areas are the most susceptible to sediment and accumulation of fine soil particles and organic matter. Furthermore, when flooding happens and soil erosion and sediment transport takes place, it can lead to the loss of highly fertile topsoil resulting in a redistribution of coarse particles which affects soil texture gradients and landform morphology. Flooding can also lead to changes in water drainage characteristics, soil fertility and biochemistry, and land use suitability, which requires careful management and likely rehabilitation measures to restore soil productivity when texture changes due to flooding. The impacts of flooding events on soil’s physical properties vary depending on factors such as the flooding duration, intensity, and upstream soil type which determines the amount and size of soil particles being transported.

3.4. Flooding Effects on Soil Organic Matter Turnover

In most soils, soil organic matter (SOM) is made up of compounds containing carbon found in soils which could part of living organisms (microbes, animals [large and small] and plants) or decay living organisms; SOM is intimately involved in regulating ecosystem functions and structure. SOM can be divided into three constituents: particulate organic matter (POM), dissolved organic matter (DOM), and mineral-associated organic matter. The physical properties and arrangements and concentrations of the different forms of SOM present in any given soil are the main factors controlling the soil SOM fate during flooding events. Research has shown that total precipitation and resulting flooding discharge and total discharge volume are the main factors controlling the concentrations of suspended mineral-associated, DOM, and POM loads. Soil food webs, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration is modulated mainly by DOM. A mixture of complex organic substances makes up DOM, including humic acids, fulvic acids, amino acids, carbohydrates, polysaccharides, and N-containing molecules such as proteins, DNA, RNA and others. Flooding events have a significant effect on DOM composition in soil and aquatic ecosystems. The concentration of DOM in water increases during flooding events in response to the leaching of originally fixed organic matter in soils. During flood events, the presence of rain and shallow groundwater can exacerbate the potential for DOM loss from agricultural soils due to increased dissolution of SOM (Clark et al., 2008). Dissolved organic matter is ever-present in flood and drainage waters and has been reported to be the main form of SOM and its constituents, including C, N, and P, in flooding water.

4. Changes in Soil Chemical Properties Due to Flooding

Flooding events can cause significant changes on soil chemical properties as a result of water loging and erosion. Examples of how flooding can change chemical properties include changes in nutrient dynamics and nutrient cycling, changes in pH levels as a result of addition of alkaline or acidic materials, influences on SOM content, nutrient availability such as N, P, S, K, and others, alterations in soil chemical composition, and, ultimately, soil fertility. Developing a good understanding about these changes in soil chemical properties is critical for developing and managing soil health, nutrient cycling, and agricultural productivity in flood-prone areas.

4.1. Soil pH and Acidity/Alkalinity

Flooding can alter soil pH levels by the addition of alkaline or acidic materials, which might influence nutrient cycling and availability due to its impacts on microbial activity. When oxygen is depleted because of flooding, the resulting anaerobic conditions promote the production and release of organic acids which can have a significant impact on soil pH. For example, a flooding experiment conducted in Florida, reported that flooding caused soil to exhibit compaction which reduced water content, leading to anaerobic conditions and increased soil pH (Li et al., 2007). Other studies reported that flooding and drying events also affect soil properties, such as pH, redox potential, and ionic strength (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2019).

4.2. Nutrient Dynamics: Availability, Losses and Redistribution

Flooding can result in nutrient losses or redistribution throughout the soil profile due to leaching, erosion, and sediment deposition. Many nutrients such as N, P, K, S, Fe, Mn, and others can become susceptible to leaching as a result of flooding events, leading to soil nutrient depletion and potentially causing pollution of water ecosystems. The driving factor of change in the dynamics and cycling of nutrients in flooded conditions is the absence of oxygen in the soil and, hence, anaerobic conditions. The loss of oxygen in the soil favors the rapid shift from aerobe to anaerobes (microbes capable of anaerobic respiration). This change in microbial community also causes a change in the compounds used as electron acceptors during metabolic activities, from oxygen to compounds such as nitrate, iron, sulfate, and manganese. Anaerobic respiration leads to chemical changes in these elements and can enhance or decrease their mobility in soils. Anaerobic conditions can also increase the release of elements that are known to be toxic to plants, such as arsenic, lead, cadmium and others (Akpoveta et al., 2014; Ponting et al., 2021). Nutrient in flooded soils can range from being more available to having their availability decreased by as much as two to four times lower than that in well-oxygenated soil (Furtak et al., 2023). For example, nutrients that are used in redox reactions such as Fe, Mn, and S can have availability increased to a point where they could cause plant toxicity, depending on initial concentrations and length of flooding (Unger et al., 2009). Other nutrients such as nitrate can be depleted, while other can increase solubility such as phosphorus and potassium. In floodplains, changes in nitrogen cycling in flooded soils happens as result of decreases in oxygen concentrations which results in denitrification (conversion of nitrate into nitrous oxide), the accumulation and volatilization of ammonia, and also nitrate leaching as flooding water recedes (Grinham et al., 2024). Organic matter decomposition can also decrease leading to accumulation of organic acids that can also be detrimental to plant growth. For example, reduced lignin decomposition in flooded soils can lead to accumulation of phenolic acids that can cause allelopathy to grass type crops such as corn, rice and wheat (Blum, 1996; Janovicek et al., 1997; Unger et al., 2009). Radicle of germinating corn seeds can have their growth inhibited by certain phenolic compounds which could lead to decreased yield. Phenolic compounds can also affect availability of nitrogen for plants after flooding (Unger et al., 2009).

The effect flooding has on chemical and biological processes impacts phosphorus availability in soil through complex mechanisms. The reductive reactions caused by anoxic conditions leads to dissolution of minerals which in turn releases phosphorus into the soil solution, as a result soluble phosphorus concentrations in flooded soils can potentially increase (Wang et al., 2022). Increased soluble phosphorus concentration in the soil solution increases its potential for losses when the flooding water recedes and also increases its availability in the soil during the first weeks of waterlogging (Maranguit et al., 2017). However, as the soil water content drop below saturation and oxidation reactions return to control soil chemical potential, phosphorus availability decreases to a new equilibrium. Significant risks for phosphorus losses are present when flooding happens because phosphorus can be lost as dissolved phosphorus as well as particulate-bound phosphorus as a result of erosion. Ding et al. (2024), investigated the effects of repeated flooding and subsequent drying cycles on calcareous soils, the authors reported that the content of colloidal phosphorus during the flooding event was always greater than that of the drying event for flooding and drying cycles. An incubation study tested the effects of soil moisture content on phosphorus solubility and availability, and the authors reported that the soil which was maintained under extended anoxic conditions had increased available phosphorus and, subsequently, the risk of phosphorus transport to aquatic ecosystems also increased (Rupngam et al., 2023). Other studies have reported that P released from anaerobic acidic soils was correlated with the reductive dissolution of Fe and Mn phosphates as a result of anaerobic conditions (Scalenghe et al., 2012). As mentioned before, flooding can have a significant impact on soil pH and cause reduction of metals that phosphorus binds to in the soil which increases phosphorus concentration in the soil solution.

Changes in soil chemical composition can also be observed because of flooding, which can also affect nutrient concentrations, soil mineralogy, and increase redox reactions in saturated soils (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2017). The redox reaction in soils leads to reductive dissolution of minerals such as Mn, Fe, and others, increasing the release of these metals in addition to other tracy metals including metalloid elements into the soil solution and can also impact soil fertility and contaminant transport (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2017). As mentioned before, sediment deposition resulting from flooding waters, can also redistribute nutrients across agricultural fields and other landscapes, which ultimately influences nutrient availability and plant growth in flood impacted areas. However, in some cases, nutrient availability might be decreased, for example phosphorus sorption onto sediments and organic matter may reduce phosphorus availability and affect nutrient cycling in aquatic ecosystems. The impact of flooding on soil chemical properties, therefore, can have a significant impact on soil fertility and crop productivity in agricultural areas.

5. Impact of Flooding on Soil Biological Properties

5.1. Flooding Impacts on Microbial Communities

Soil microbial communities are the most important players for soil processes, and their stability and resilience are central to the response of soil to environmental stresses (Das et al., 2025). Global climate change will most certainly increase the frequency and intensity of soil flooding and will become the future major environmental stressors of agroecosystems. One of the most important negative consequences of soil water logging is the depletion of oxygen and resulting anoxic conditions due to the accumulation of stagnant water on the soil (Baldwin and Mitchell, 2020; Das et al., 2025). Another concern that arises from flooding is the impact on soil carbon cycling and its availability to microbial life, which when limited will impact microbial metabolism. Under anoxic conditions, soil microbial communities’ diversity and composition can be profoundly altered (Wang et al, 2015, Nguyen et al., 2018). These changes can lead to the predominance of anaerobic communities over aerobic communities, however, both communities will still have some sort of a role in nutrient cycling. The prevalence of anaerobic communities over aerobic ones is evidenced by the changes in soil functions which affect the resilience of the ecosystem that is under stress (Baldwin and Mitchell, 2020). Under anaerobic conditions microorganisms will use alternative electron acceptors such as Fe, Mn, NO32-, SO42-, and CO2, for organic matter decomposition and energy production. The metabolic activity under anaerobic conditions leads to the production of fermentation by-products, such as methane, hydrogen sulfide, organic acids, which will have a significant effect on soil pH, redox potential, and nutrient cycling and availability. These changes can be transient and are likely to lead to a progressive shift from aerobic to anaerobic communities.

In summary, shift in microbial communities influence organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, contaminant mobility, and soil biogeochemical processes in general with implications for soil health and productivity.

5.2. Soil Enzymatic Activity in Water-Logged Soils

Because the majority of soil enzymes are of microbial origin, the fate of enzyme activities and microbial communities in soil environments are intertwined. In soils, enzymes are usually the products of free-living microorganisms, but can also have a plant origin. Any impact of flooding on soil microorganisms can have ripple effects on soil enzyme activity. Therefore, flooding will have a significant impact on soil enzyme activity and on the presence of a diverse microbial community, including mycorrhizal fungi and other fungi groups, and bacteria including Gram-negative and positive, and also archaea. In an incubation study where soils were exposed to flooding for a period of 60 days, it was reported that microorganism such as fungi were more sensitive than bacteria flooding conditions were introduced (Cao et al., 2020). As mentioned previously, flooding can have a significant effect on nutrient cycling and the energy necessary for metabolism reactions linked with enzyme activity. In flooded soil, enzyme activity can be significantly impacted by Cu content and its impact on the richness and diversity of bacterial and fungal communities (Cao et al., 2020). Several enzymes have been reported to have their activity decreased under conditions of high Cu concentration in flooded soils due to the suppression of cellular activities and inactivation of extracellular enzymes, examples of enzymes include urease, invertase, and cellulase (Kunito et al., 2001).

In a greenhouse experiment were lysimeters were used, Rupngam et al. (2023) compared soil moisture regimes, including waterlogging, on soil enzyme activity for various enzymes, in addition to P leaching, and plant development and growth. The results of the study showed that the activity of soil enzymes β-glucosidase and acid phosphomonoesterase decreased under waterlogging; and in contrast, the activity of N-acetyl-β-glycosaminidase increased. The results led the authors to conclude that since these enzymes control the hydrolysis of cellulose, phosphomonoesters, and chitin, soil moisture content impacts the direction and magnitude of nutrient release and availability, including carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. Another process of interest is mineralization, which breaks down organic into inorganic compounds which is also in many cases mediated by soil enzymes.

The activity of other soil enzymes including polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase, which are usually two extracellular enzymes present in most agricultural soils, can also be affected by flooding and its effects on metal solubility during flooding conditions. Research reported in the literature have shown soluble metal in soils can have interactive effects with phenolic compounds, and become an inhibitor for certain enzymes, and therefore, play a major role in microbial activity, organic matter and decomposition rates, and also nutrient cycling. Researchers have reported that soil microbial metabolic activity can be limited as a result of a gradient of flooding duration and intensity (Huang et al., 2023). Huang et al. (2023) also reported that the effects of flooding on microbial metabolic activity had a negative impact mainly on carbon and phosphorus cycling.

6. Potential Implication of Implementing the FM Diversion Project:

6.1. Impact on Soil Productivity

Although flooding can cause soil compaction, the type of compaction resulting from flooding is different than compaction caused by field implements or animal traffic. Tractors and other implements are extremely heavy, and all the weight is concentrated on the wheels of the machinery which impacts about 14% of an acre through direct travel. For all practical purposes travel with field equipment only takes place in unsaturated soils which are much more susceptible to compaction than flooded soils. In contrast, flooding adds a large amount of weight to a large area, and the impact on soil properties will vary dramatically compared with heavy machinery. For example, a 2-foot flooding would have a pressure of 125 lb/ft2 and the weight of the water on a whole acre would be 125 lb/ft2 x 43,560 ft2 = 5,500,000 lb, which is applied to the entire field at once. In contrast, a plot combine with a half-full grain tank can exert a pressure of 6,500 lb/ft2 when in travel, and with a total weight of approximately 90,000,000 lb (6,500 lb/ft2 x 6,800 ft2 [area of an acre impact by the wheel during travel] x 2 axels where the weight is) being travelled on 14% of an acre.

The compaction caused by traffic on unsaturated soil will cause severe compression of soil particles which will lead to significant increases in soil bulk density and decrease total porosity. Most impact of traffic is usually noticed below the soil surface and can vary from 6” to 12” and even deeper. In contrast, flooding induced soil compaction has a less dramatic impact, but nonetheless the effects can have significant impact on soil productivity. During flooding, the water displaces air from the soil causing saturation of most pores, because there is little air in the saturated soil traditional compaction (as caused by travel) is not possible. Instead, with prolonged flooding, soil aggregates can start to lose strength which can cause them to collapse. Aggregate collapse can lead to a reduction in drainage pores and an increase in storage porosity. This can significantly impact drainage and the amount of soil available water (the water which plants use). In addition, it can also impact soil microbiology and nutrient cycling by changing how water is being stored and moving in the soil profile. Lack of soil structure can also increase soil resistivity, influence root growth and proliferation, and become more susceptible to erosion. Soil erosion can be a significant source for lower productivity of a field. The topsoil is the soil layer most fertile as it is the most active with microbes and plant roots interacting and cycling organic matter. However, the topsoil is the soil layer most susceptible to water and wind erosion and having a good structure is one of the best ways to minimize the loss of soil due to erosion. When flooding disrupts the process of aggregate formation and also breaks down structure making the topsoil susceptible to erosion as the water recedes or as water rush into a field.

In isolation, compaction due to flooding is unlikely to be a severe issue and potential tillage operations and other best management practices could help alleviate this issue. However, depending on amount of water and duration of flooding, changes in other soil properties can aggravate the impact of flooding on soil productivity. Soil saturation causes anaerobic conditions to develop and with that a cascade of biochemical changes can take place. First, with flooding aerobic conditions switch to anaerobic and the main pathway for respiration switches from oxygen to compounds such as nitrate, iron, manganese, and sulfur. The change in microbial community causes a change in organic matter deposition and nutrient cycling. In terms of negative impacts, the following could take place under such conditions:

- -

Impact on Nitrogen: Depending on severity and flooding duration significant amounts of N can be lost from the system. Increased break down of organic matter, releases increased levels of ammonium to the soil solution, causing a reduction in potentially mineralizable nitrogen (nitrogen that would become available throughout the growing season); nitrate that is present in the soil can be denitrified and lost to the atmosphere; nitrate and ammonium that might be in solution will leach with the receding and draining water. The amount of nitrogen a corn crop can remove on an acre basis can be around 350 lb N ac-1 for a yield of 220 bu ac-1, and for this yield farmers will usually add 200 lb N ac-1 applied at some point in the spring. The difference in nitrogen taken up by corn (350 – 200 = 150 lb N ac-1) is supplied by the soil by means of residual nitrate from the previous season combined with ammonium mineralized from organic matter. The anaerobic conditions caused by flooding early on can reduce the amount of total nitrogen supplied by the soil. Which could cause a deficit in total nitrogen in the system and increase the amount of nitrogen the farmer would have to supplement. Increasing the final cost of production and reducing profits for the farmer.

- -

Impact on Phosphorus: Phosphorus can be impacted by flooding in two ways, inorganic phosphorus can be solubilized as metals are reduced during oxi/redox reactions and organic matter decomposition can also increase the amount of inorganic phosphorus in solution. The increase in inorganic phosphorus in solution can increase the amount of phosphorus that leave the system primarily as the flooding water recedes which can cause pollution. In terms of phosphorus availability, it is unclear how flooding can really impact soil phosphorus availability in this region. Depending on soil test levels, increased amounts of fertilizer phosphorus would have to be added to compensate for phosphorus lost during flooding.

- -

Impact on soluble nutrients: Nutrients such as potassium that are soluble have high risk of being lost by leaching because of flooding. Nutrients such as sulfur, iron and manganese can also be lost by leaching as well when in a reduced form. As with all nutrients, increased amount of fertilizer will likely be needed to be applied to replenish the nutrients being lost.

- -

Impact on organic matter decomposition: Organic matter decomposition changes under flooding conditions and the rate of breakdown and processes involved in the breakdown changes significantly. Carbon is converted into methane and lignin breakdown slows down and potentially stops. The change in microbial community can lead to the development of conditions that can hinder crop development, such as the accumulation of phenolic acids which is linked to decreased seeding growth. As a result, there is potential for further reduction in productivity.

Early in the spring as soil temperature starts to increase so does the activity of microorganisms, and, as a result increased nutrient cycling. Depending on when flooding takes place in the spring and the soil temperatures, an increased potential for nutrient loss could be observed.

6.2. Impact on Crop Yield

Delayed planting is often the easiest way to estimate potential yield loss because of flooding. In a study in southwestern MN researchers found that delaying planting by 4 weeks and longer caused corn yield reduction of 15 – 30% (Van Roekel and Coulter, 2011). Others have reported significant yield reductions for soybeans planted late in May and early June in an Iowa trial (De Bruin and Pedersen, 2008). Sugar beet yield In Wyoming was found to decrease by as much as 38% in a 46-day delayed planting with a 4% decrease in sugar content, a 42% decrease in recoverable sucrose, and increased loss to molasses by 21% (Lauer 1997). Limited information is available for the effects of delayed planting on wheat yield, but certainly delaying planting will also lead to significant decrease in wheat yields. In most studies that investigate delayed planting, however, delayed planting is not a result of flooding but rather planting is delayed on purpose so the researchers can understand the impacts of the delay on crop yield. As indicated above, there are several changes in soil physicochemical and biological properties that can take place after a field is flooded which will also impact productivity and profitability of the flooded field.

The main concerns from a profitability and productivity standpoint are nutrient availability, soil density, and organic matter turnover rate. As indicated previously, flooding depending on intensity and duration and time when it happens, can have a significant impact on how much nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, primarily, will be available for the crop. Nitrogen being the most critical for corn, wheat and sugar beets (along with potassium). Nitrogen fertilizer is applied with the expectation that the soil will also supply a significant amount nitrogen (~40%) to the growing crop through nitrogen mineralization during the growing season. If flooding reduces the amount of nitrogen that can be supplied to the crop by the soil, then the deficit in nitrogen will also lead to a reduction in yield. Depending on how deficient the crops are in nitrogen, a certain yield reduction will happen. Similarly for other nutrients such as phosphorus and sulfur. Phosphorus and sulfur are present in organic forms in the soil and mineralization will be key for availability during the growing season. As a result, flooding will significantly impact crop yield indirectly because nutrient mineralization is heavily dependent on soil enzymes and flooding can disrupt enzyme activity. There is no research that has been able to put an economic value on yield loss due to flooding impacting nutrient cycling, which makes it difficult to estimate potential financial losses. However, the potential for the loss in nutrient cycling is evident in the peer-reviewed literature.

Another issue that can happen depending on flooding timing, size, and duration, is changes in soil density due to particle rearrangement due to aggregate collapse and particle deposition (Ghazavi et al., 2010, Mungai et al., 2011). Denser soils will provide higher resistivity to root growth and development which exacerbates the issues of nutrient cycling as plants are limited to exploring a minimized area within the soil profile. In addition, water infiltration rates can decrease which could extend the actual dry down time, taking longer for field to dry than models predict (the 10 to 14 days dry down which are usually used [Bangsund et al., 2020]). One of the pitfalls of modeling, is that is assumes that no changes in soil structure and porosity will take place due to flooding because this information is not available. The information available suggests that it is possible for flooding to cause significant changes in soil physicochemical and biological properties that can negatively impact soil productivity and impact planting date.

7. Final Considerations

The effects that flooding might have on soil properties in agricultural areas affected by the FM Diversion project, will depend on each case, however, generalized assumptions can be made. Flooding soils that are not constantly flooded (maybe once in ten to fifteen years) will have a different impact than flooding areas that flood every year. Changing flooding duration and volume can also have a significant impact on agricultural soils.

It is possible that areas which were not constantly flooded but will have yearly floods after implementation of the project might have changes in soil properties which could lower the potential for productivity and profitability of the land. For example, decreases in the rate and timing of organic matter and nutrient cycling and availability could cause the land to only produce a fraction of what the production potential was before. Perhaps a corn potential of 180 bu acre-1 is now 160 bu acre-1, similar results could be observed for any other crop as the production potential of the soil likely will not be restricted to one crop only. Options that farmers might have to try and offset decreased nutrient supply by the soil would by the application of supplementary fertilizer, which would increase the cost of production and decrease profits.

Nonetheless, potential decreases in soil productivity might not only be linked to biochemical processes but might also be due to changes to physical properties. The amount of water stored in the soil and the ease with which roots penetrate the soil are also very important productivity factors. Together, all of these small effects when analyzed alone might not seem detrimental, but when combined they can have a serious negative impact on productivity.

However, such changes in soil properties might not happen after one or two flooding events, it could take time, potentially decades before significant changes can be noticed, measured, and economic loss starts. Changes can also happen quicker depending on flooding size, duration, volume, and soil properties. The contrasting case scenario is also possible, where productivity improves in cases where flooding no longer takes place. Therefore, it is not possible to say with certainty what will happen in each case and to draw strong conclusions to the true potential of flooding on soil production potential, but the potential for changes that can significantly impact crop production is a phenomenon well understood in the scientific community.

References

- Akpoveta, V.O.; Osakwe, S.A.; Ize-Iyamu, O.K.; Medjor, W.O.; Egharevba, F. Post flooding effect on soil quality in Nigeria: The Asaba, Onitsha experience. Open Journal of Soil Science 2014, 4, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, A.; Rogger, M.; Peth, S.; Blöschl, G. Does soil compaction increase floods? A review. Journal of hydrology 2018, 557, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschonitis, V.G.; Kostopoulou, S.K.; Antonopoulos, V.Z. Methodology to assess the effects of rice cultivation under flooded conditions on van Genuchten’s model parameters and pore size distribution. Transport in Porous Media 2012, 91, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D.S.; Mitchell, A.M. The effects of drying and re-flooding on the sediment and soil nutrient dynamics of lowland river–floodplain systems: a synthesis. Regulated Rivers: Research & Management: An International Journal Devoted to River Research and Management 2000, 16, 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Banach, A.M.; Banach, K.; Peters, R.C.J.H.; Jansen, R.H.M.; Visser, E.J.W.; Stępniewska, Z.; Roelofs, J.G.M.; Lamers, L.P.M. Effects of long-term flooding on biogeochemistry and vegetation development in floodplains; a mesocosm experiment to study interacting effects of land use and water quality. Biogeosciences 2009, 6, 1325–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsund, D.A.; Shaik, S.; Saxowsky, D.; Hodur, N.M.; Ndembe, E. 2020. Assessment of the Agricultural Risk of Temporary Water Storage for the FM Diversion Staging Area.

- Batey, T. Soil compaction and soil management–a review. Soil use and management 2009, 25, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, U. Allelopathic interactions involving phenolic acids. Journal of Nematology 1996, 28, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Cameira, M.R.; Fernando, R.M.; Pereira, L.S. Soil macropore dynamics affected by tillage and irrigation for a silty loam alluvial soil in southern Portugal. Soil and Tillage Research 2003, 70, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Pan, J.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xu, P.; Chen, M.; Guan, M. Water management affects arsenic uptake and translocation by regulating arsenic bioavailability, transporter expression and thiol metabolism in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 206, 111208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liang, Q.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, S. Remote-sensing disturbance detection index to identify spatio-temporal varying flood impact on crop production. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2019, 269, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.M.; Lane, S.N.; Chapman, P.J.; Adamson, J.K. Link between DOC in near surface peat and stream water in an upland catchment. Science of the Total Environment 2008, 404, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Lee, D.S.; Woo, Y.J.; Sultana, S.; Mahmud, A.; Yun, B.W. The Impact of Flooding on Soil Microbial Communities and Their Functions: A Review. Stresses 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, J.L.; Pedersen, P. Soybean seed yield response to planting date and seeding rate in the Upper Midwest. Agronomy Journal 2008, 100, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Du, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Changes in the pH of paddy soils after flooding and drainage: Modeling and validation. Geoderma 2019, 337, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Q. Restricted colloidal-bound phosphorus release controlled by alternating flooding and drying cycles in an alkaline calcareous soil. Environmental Pollution 2024, 343, 123204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, K.; Wolińska, A. The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture–A review. Catena 2023, 231, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazavi, R.; Vali, A.; Eslamian, S. Impact of flood spreading on infiltration rate and soil properties in an arid environment. Water resources management 2010, 24, 2781–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinham, A.; Costantini, T.; Deering, N.; Jackson, C.; Klein, C.; Lovelock, C.; Pandolfi, J.; Eyal, G.; Linde, M.; Dunbabin, M.; Duncan, B. Nitrogen loading resulting from major floods and sediment resuspension to a large coastal embayment. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 918, 170646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Wen, X.; Liu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Fu, C.; Zheng, B.; Gong, L.; Zhan, H.; Ni, Y. Flooding dominates soil microbial carbon and phosphorus limitations in Poyang Lake wetland, China. Catena 2023, 232, 107468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovicek, K.J.; Vyn, T.J.; Voroney, R.P.; Allen, O.B. Early corn seedling growth response to phenolic acids. Canadian journal of plant science 1997, 77, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, G.; Motavalli, P.P.; Nelson, K.A.; Orlowski, J.M.; Golden, B.R. Impacts and management strategies for crop production in waterlogged or flooded soils: A review. Agronomy Journal 2020, 112, 1475–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodikara, J.; Islam, T.; Sounthararajah, A. Review of soil compaction: History and recent developments. Transportation Geotechnics 2018, 17, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulou, S.; Kallitsari, C.; Aschonitis, V. Seasonal flooding and rice cultivation effects on the pore size distribution of a SiL soil. Agriculture and agricultural science procedia 2015, 4, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunito, T.; Saeki, K.; Goto, S.; Hayashi, H.; Oyaizu, H.; Matsumoto, S. Copper and zinc fractions affecting microorganisms in long-term sludge-amended soils. Bioresource Technology 2001, 79, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, J.G. Sugar beet performance and interactions with planting date, genotype, and harvest date. Agronomy journal 1997, 89, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; McCoy, C.W.; Syvertsen, J.P. Controlling factors of environmental flooding, soil pH and Diaprepes abbreviatus (L.) root weevil feeding in citrus: larval survival and larval growth. Applied Soil Ecology 2007, 35, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peachey, B.; Maeda, N. Global warming and anthropogenic emissions of water vapor. Langmuir 2024, 40, 7701–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manik, S.N.; Pengilley, G.; Dean, G.; Field, B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M. Soil and crop management practices to minimize the impact of waterlogging on crop productivity. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranguit, D.; Guillaume, T.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of flooding on phosphorus and iron mobilization in highly weathered soils under different land-use types: Short-term effects and mechanisms. Catena 2017, 158, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungai, N.W.; Njue, A.M.; Abaya, S.G.; Vuai, S.A.H.; Ibembe, J.D. Periodic flooding and land use effects on soil properties in Lake Victoria basin. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2011, 6, 4613–4623. [Google Scholar]

- Myhre, G.; Samset, B.H.; Schulz, M.; Balkanski, Y.; Bauer, S.; Berntsen, T.K.; Bian, H.; Bellouin, N.; Chin, M.; Diehl, T.; Easter, R.C. Radiative forcing of the direct aerosol effect from AeroCom Phase II simulations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2013, 13, 1853–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Osanai, Y.; Anderson, I.C.; Bange, M.P.; Tissue, D.T.; Singh, B.K. Flooding and prolonged drought have differential legacy impacts on soil nitrogen cycling, microbial communities and plant productivity. Plant and Soil 2018, 431, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, D.H.; Cordery, I. Rainfall temporal patterns for design floods. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1975, 101, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, J.; Kelly, T.J.; Verhoef, A.; Watts, M.J.; Sizmur, T. The impact of increased flooding occurrence on the mobility of potentially toxic elements in floodplain soil–A review. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 754, 142040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.H.; Okubo, A.; Sugiyama, S.; Mayland, H.F. Physical, chemical and microbiological properties of an Andisol as related to land use and tillage practice. Soil and Tillage Research 2008, 101, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupngam, T.; Messiga, A.J. Unraveling the interactions between flooding dynamics and agricultural productivity in a changing climate. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupngam, T.; Messiga, A.J.; Karam, A. Soil enzyme activities in heavily manured and waterlogged soil cultivated with ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). Canadian Journal of Soil Science 2023, 104, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupngam, T.; Messiga, A.J.; Karam, A. Solubility of soil phosphorus in extended waterlogged conditions: An incubation study. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.R.; Hill, P.W.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Crop residues exacerbate the negative effects of extreme flooding on soil quality. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2017, 53, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalenghe, R.; Edwards, A.C.; Barberis, E.; Ajmone-Marsan, F. Are agricultural soils under a continental temperate climate susceptible to episodic reducing conditions and increased leaching of phosphorus? Journal of environmental management 2012, 97, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sîli, N.; APOSTU, I.; Faur, F. Floods and their effects on agricultural productivity. Research Journal of Agricultural Science 2020, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, L.J.; Villarini, G. Recent trends in US flood risk. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 12–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, I.M.; Kennedy, A.C.; Muzika, R.M. Flooding effects on soil microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology 2009, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, I.M.; Motavalli, P.P.; Muzika, R.M. Changes in soil chemical properties with flooding: A field laboratory approach. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2009, 131, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Van Roekel, R.J.; Coulter, J.A. Agronomic responses of corn to planting date and plant density. Agronomy Journal 2011, 103, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglione, A.; Blöschl, G. On the role of storm duration in the mapping of rainfall to flood return periods. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2009, 13, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Z.; Ma, J.; Xu, H.; Jia, Z. Differential contributions of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers to nitrification in four paddy soils. The ISME journal 2015, 9, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Manandhar, B.; Nitivattananon, V.; Fang, X.; Huang, W. A review of the flood management: from flood control to flood resilience. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2024. World Health Organization. Floods. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/floods#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 13 Ma 2025).

- Zhu, Z.; Wright, D.B.; Yu, G. The impact of rainfall space-time structure in flood frequency analysis. Water Resources Research 2018, 54, 8983–8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).