1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Large language models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT have rapidly entered education as potential teaching assistants [

1]. Recent studies and meta-analyses confirm that ChatGPT-based interventions can significantly improve student learning outcomes. For example, a recent meta-analysis reported a significant overall effect (Hedges’ g ≈ 0.87) on learning performance in favor of ChatGPT-assisted learning [

2]. However, ensuring these AI tools promote genuine learning (rather than simply giving students answers) remains challenging [

3].

In mid-2025, OpenAI released GPT-5 [

4] – a state-of-the-art model with greatly improved reasoning and coding abilities [

5] – along with a new Study Mode designed for education [

6]. In Study Mode, ChatGPT provides step-by-step Socratic guidance instead of direct answers [

5,

6]. This design is intended to align the AI with sound pedagogy by encouraging active engagement, managing cognitive load, and prompting student reflection [

7]. As one expert noted, even in the AI era, the best learning still happens when students are excited about and actively engaging with the lesson material [

8,

9] – in other words, the goal of Study Mode is to leverage AI as a catalyst for such active learning rather than a shortcut to answers.

In a comparative study, Kroustalli and Xinogalos found that a CodeCombat-based course led to slightly better post-test performance (though not statistically significant) than traditional instruction, and students rated the game highly in perceived usefulness and ease of use [

10]. The immersive, level-based format of the game was credited with keeping students engaged. These insights set the stage for blending gamified learning with AI tutoring in our approach.

1.2. Research Gap and Motivation

While numerous quantitative studies have examined ChatGPT in higher education, there is a lack of in-depth qualitative research on how AI tutors might transform learning processes in elementary programming classrooms. In particular, we know relatively little about young students’ behaviors, problem-solving strategies, and self-regulatory skills when a game-based coding platform is combined with an LLM-based tutor.

Our study seeks to fill this gap by examining an intervention in a primary school programming course that integrated CodeCombat with ChatGPT’s Study Mode. We investigate three dimensions:

(1) Learning Achievement – the qualitative characteristics of students’ learning performance (e.g. level-completion strategies, debugging approaches, solution explanations) under the combined use of CodeCombat and ChatGPT;

(2) Learning Motivation – changes in students’ motivation and self-efficacy in programming resulting from the Study Mode experience;

(3) Self-Regulated Learning – developing students’ self-regulatory behaviors (such as goal setting, progress monitoring, and strategy adaptation) in this AI-supported, game-based learning context.

The goal is to characterize the learning patterns emerging from the synergy of a gamified platform and an AI tutor and identify this approach’s practical benefits and limitations for young learners.

1.3. Research Questions:

Based on the background and the identified research gap, this study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1 (Learning Achievement): How does combining CodeCombat with Study Mode affect students’ learning performance in Python programming education?

RQ2 (Learning Motivation): How does Study Mode affect students’ motivation and self-efficacy in Python programming education?

RQ3 (Self-Regulated Learning): How does Study Mode influence students’ goal setting, self-monitoring, and strategy adjustment during Python programming tasks?

2. Related Works

2.1. ChatGPT and Student Learning Achievement

Research has suggested that AI-based chatbots may enhance students’ learning outcomes [

11]. Comprehensive analyses report positive effects on academic performance and higher-order thinking skills [

12]. In particular, using ChatGPT as an intelligent tutor – providing hints, explanations, and interactive feedback–has yielded substantial gains in students’ higher-order thinking and problem-solving abilities [

13]. For example, in controlled comparisons where one group received guided tutoring from ChatGPT and another did not, the ChatGPT-tutored students demonstrated significantly better critical thinking and creativity in their solutions [

14].

However, researchers have cautioned that how students use the AI is crucial. If an AI chatbot provided complete answers or code, students could bypass the cognitive effort needed for learning. Jošt et al. [

15] observed that undergraduates who relied heavily on ChatGPT or GitHub Copilot to generate code and debug assignments ended up with lower course grades than their peers; by contrast, those who used these tools mainly for hints, explanations, or code review did not experience this negative effect. In other words, the unrestricted use of ChatGPT as an “answer vending machine” could undermine learning, whereas using it as a guide or on-demand mentor is far more beneficial [

15].

Early evaluations of ChatGPT in education highlighted this dual potential. On one hand, ChatGPT offered instant explanations, examples, and personalized feedback on demand [

16], which helped students overcome roadblocks in understanding concepts or debugging code. On the other hand, educators and experts warned of pitfalls: the risk of factual inaccuracies, plagiarism, and the erosion of students’ independent critical thinking skills if they became over-reliant on AI-generated answers [

3]. Kasneci et al. [

17] encapsulated these opportunities and challenges in their 2023 review: they noted that ChatGPT could function as a personalized tutor and provide rich, adaptive feedback to learners. However, they emphasized the importance of guided use policies to prevent academic dishonesty and ensure students practice problem-solving independently.

In summary, the literature has suggested that ChatGPT can significantly enhance learning achievement when used as a source of hints, feedback, and Socratic questioning rather than as a source of ready-made solutions [

15]. This principle underlies the design of ChatGPT’s Study Mode and guides our deployment of the AI in this study.

2.2. ChatGPT and Learning Motivation

ChatGPT’s impact on student motivation and engagement has attracted research attention. A recent systematic review found that ChatGPT-based learning had a positive influence on student engagement, with particularly notable improvements in students’ cognitive engagement (e.g., deep thinking, curiosity) when the AI was used in an interactive, tutoring capacity [

18,

19]. The conversational nature of tools like ChatGPT can make learning feel more personalized and immediate for students, which in turn sustains their interest.

For instance, Heung and Chiu [

18] reported a moderate overall effect of ChatGPT on learners’ motivation and attitudes, and they attributed this to ChatGPT’s ability to provide timely encouragement, tailored explanations, and a sense of “partnership” in problem-solving. Students often described the AI as an always-available study companion that kept them engaged by answering questions whenever they arose.

Moreover, AI-based chatbots have played multiple supportive roles – such as a tutor guiding a student through a solution, a programming assistant helping to debug code, or even a collaborative brainstorm partner for projects – all of which can increase a learner’s intrinsic interest and investment in the task [

1,

16].

In programming education, researchers have noted that immediate, trial-and-error feedback is key to sustaining motivation [

20]. ChatGPT, when used in Study Mode, provides this instant feedback loop: it answers students’ questions step-by-step and offers hints when they get stuck, which can reduce frustration and encourage perseverance. This aligns with prior findings from game-based learning, where instant feedback and achievable challenges boost learners’ engagement. In our context, the CodeCombat game has already contributed to gamified motivation [

10], and adding ChatGPT’s guidance is expected to further support students’ interest and confidence.

In summary, maintaining authentic motivation- instead of motivation merely to get straightforward answers – requires careful implementation. When the AI asked probing questions or suggested next steps (instead of just giving the solution), it sparked curiosity and a sense of challenge in the learner, which are known drivers of intrinsic motivation.

Our study will examine whether young students exhibit increased enthusiasm or self-efficacy with the introduction of ChatGPT’s guided tutoring, and we will also note any motivational drawbacks, for example, if some students feel less confident in their abilities or become anxious about using AI.

Overall, existing research points to a cautiously optimistic view: used as an interactive guide, ChatGPT can make learning more engaging and enjoyable for students [

18], but it should be implemented in ways that reinforce rather than replace students’ effort and sense of accomplishment.

2.3. ChatGPT and Self-Regulated Learning

A key question for educators is whether AI tutors like ChatGPT foster or hinder students’ self-regulated learning (SRL) skills. Self-regulation involves learners setting goals, monitoring their understanding, and reflecting on their progress – habits that develop best when students actively grapple with material. Emerging evidence is that a guided use of ChatGPT can actively promote SRL.

Lee et al. [

21] introduced a “Guidance-based ChatGPT-assisted Learning Aid (GCLA)” framework, which required students to attempt problems on their own before ChatGPT offered any help. Crucially, even when help was given, the AI provided only hints or probing questions (never the complete answer) to encourage reflection. In a randomized trial in an undergraduate course, this guided approach led to significantly higher SRL skills and higher-order problem-solving performance compared to a group with unrestricted ChatGPT use. Students using the guided ChatGPT aid were more proactive in checking their work and planning next steps, indicating that the AI’s scaffolding helped instill better study habits.

Similarly, Lee and Wu [

14] implemented a variant in which ChatGPT acted as a peer in a structured peer-assessment cycle, giving students feedback on their work and asking questions about their reasoning. They found that this approach (dubbed “PA-GPT”) not only improved content learning but also strengthened students’ critical thinking and self-evaluation skills – key components of SRL. These results aligned with the notion that AI tutors should act as facilitators of the metacognitive process, prompting learners to explain their thinking, identify errors, and consider improvements, rather than simply providing solutions.

When designed with SRL in mind, an AI tutor can function as a form of training wheels for self-regulation: it models reflective questions a student should ask themselves and gradually transfers responsibility to the learner. An illustrative example came from Ng et al. [

22], who developed a customized ChatGPT-based tutor (“SRLbot”) to support secondary school science students’ study habits. Over the teaching experiment, students who used the ChatGPT-powered SRLbot showed enhanced motivation to maintain consistent study schedules and reported lower anxiety than a control group using a simpler rule-based chatbot.

The generative AI tutor in Ng et al.’s study [

22] adapted its prompts to each student’s progress, providing personalized reminders, encouragement, and strategy tips, which helped students set goals and reflect on their learning strategies. The SRLbot’s ability to give tailored recommendations – for example, suggesting a review of prior material if a student was stuck, or offering an extra challenge if the student was excelling – was cited as a significant advantage by the participants.

Taken together, these studies suggest that when used scaffolded, ChatGPT can aid the development of SRL behaviors. By continually engaging students in dialogues about how and why they are doing something, the AI can prompt learners to be more planful, self-monitoring, and reflective [

21,

22]. Our study will contribute qualitative evidence on this aspect in a K-12 setting. We will observe, for instance, whether fifth and sixth graders begin to emulate the AI’s questioning (e.g., asking themselves “Did I debug all possibilities?” because the chatbot habitually asks them similar questions) or whether they show more initiative in using hints and checking their code. At the same time, we remain vigilant for signs of over-reliance, as striking the right balance is essential.

Overall, the prevailing research indicates that with careful design, AI tutors like ChatGPT’s Study Mode can catalyze better self-regulation, guiding students toward habits of mind that ultimately enable them to learn independently and effectively.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The study took place in a public elementary school computer lab with one class of 25 students in primary school grades 5–6 (ages 11–12). All were Python novices. The intervention spanned three weeks, with seven sessions per week, each lasting 40 minutes.

3.2. Teaching Materials

Instructions were given using the CodeCombat CS1 Python [

23] sequence and an in-class multiplayer arena. ChatGPT’s Study Mode (“Study and Learn” interface) was introduced as a guided help tool in class and is available to students at home. The teacher modeled hint-seeking and self-check practices aligned with Study Mode’s “no direct answers” design.

The CodeCombat CS1 Python course comprised 18 levels organized into four modules that progressed from basic commands to an integrated application.

Module 1 (levels 1–8, Basic Syntax) introduced sequencing, syntax, strings, comments, and simple arguments. Students issued precise movement and action commands, read short task goals, and received immediate visual feedback that linked code to on-screen outcomes.

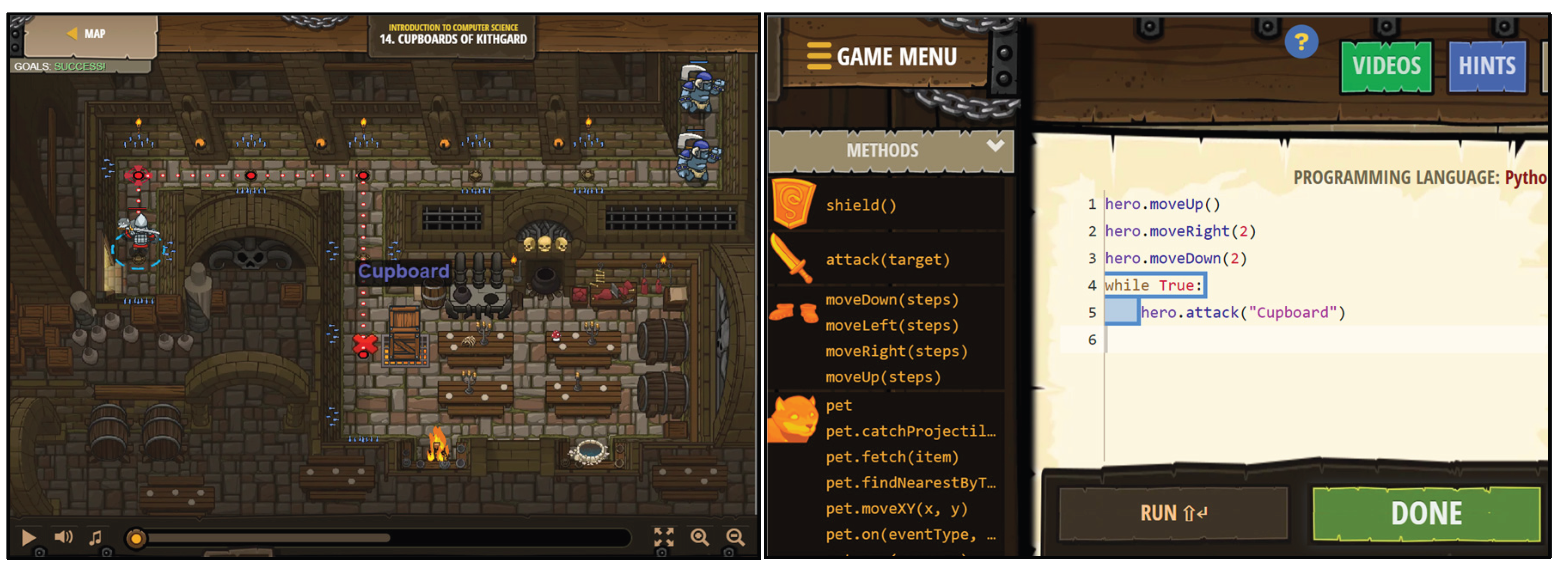

Module 2 (levels 9–14, Loops) focused on repetition. Learners refactored manual steps while True looping patterns were being used, monitored stop conditions, and practiced making minor edits, followed by quick tests to confirm control flow. To ground this instruction, we provided an example from Level 11 (Kithgard Librarian).

Figure 1 illustrates replacing repeated movement with a while True loop and adding a simple range check to decide whether to move, collect, or pause.

Module 3 (levels 15–17, Variables) added state tracking. Students created and read variables to coordinate decisions across actions, bringing together arguments, loops, and simple condition checks to solve longer sequences.

Module 4 (level 18, Capstone Challenge – Multiplayer Arena). The capstone was the Wakka Maul arena: each student chose Red or Blue and submitted Python code to control a hero. The platform ran Red–Blue matches automatically and updated a real-time leaderboard. This stage emphasized transfer and rapid iteration: students recomposed earlier patterns into a compact control skeleton (patrol, collect, engage), tuned parameters such as chase range and distance checks to avoid over-chasing, and compared patrol versus camp strategies. Although code was authored individually, peers on the same team sometimes aligned terminology and ideas, then validated changes by re-queuing matches. Study Mode was a guided reference; students requested hints to resolve disagreements and target next steps before testing again.

Within the teaching experiment, all students completed Modules 1–3 and participated in the capstone arena event; exposure to later enrichment beyond variables depended on individual pacing.

3.3. Data Collection

Data consisted of semi-structured interviews conducted after the three-week intervention. We interviewed 10 students (balanced by grade, gender, and observed progress) for 20–30 minutes each. Interviews focused on concrete episodes of Study Mode use (for example, getting unstuck or testing a code idea), perceived effects on motivation and confidence, and any changes in planning, monitoring, and help-seeking. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized (S1…S10). “S” denotes the student and the number uniquely identifies a different participant. The same code is used consistently across sections to refer to the same student.

3.4. Study Mode Tutoring

Study Mode [

6] was positioned as a guided tutor that provided hints, probing questions, and formative feedback rather than direct solutions. In the first session, the teacher demonstrated effective prompting by stating the task goal, describing current behavior, and specifying the blockage before requesting two to three next-step hints.

During class, students kept CodeCombat and Study Mode side by side, outlined a short plan before coding, and asked for debugging hints tied to an observed error or concept clarifications linked to the current level. After fixing the issue, they summarized what had changed and why, reinforcing reflection.

After class, students who encountered difficulties or had unanswered questions could use ChatGPT’s Study Mode to continue seeking guidance at home. This allowed them to revisit coding concepts, troubleshoot issues, or clarify instructions self-paced without waiting until the next scheduled lesson. This after-class accessibility reinforced continuity between sessions and encouraged learners to take greater ownership of their problem-solving process.

3.5. Data Analysis

We used an inductive thematic analysis informed by grounded theory [

24,

25]. Two researchers open-coded transcripts to identify events and statements relevant to the three research questions (learning performance, motivation/self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning). Codes were grouped into themes aligned with each RQ. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. We report themes with representative quotations that illustrate typical patterns and outliers.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: Learning Achievement

4.1.1. Instant Feedback and Formative Assessment

Students described a short try–feedback–revise loop when using Study Mode in ChatGPT during CodeCombat levels. Instead of receiving direct solutions, they received prompt-like hints that narrowed error sources (e.g., variable name mismatches, loop stop conditions). This reduced idle time and helped them keep momentum while sustaining active reasoning.

S7: “When I got stuck I typed to the chatbot and it replied super fast. It would say, ‘check that line’ or ask me what I tried. It did not just give me the answer, but I fixed stuff quicker.”

S3: “Sometimes it asked me, ‘what should stop your loop?’ and then I noticed I forgot to change the number. That felt like I found it, not like it told me.”

These exchanges show that rapid, hint-level feedback supported efficient debugging without replacing the student’s own problem-solving.

4.1.2. Programming Problem-Solving Support

Study Mode nudged students to outline intentions before coding, then respond with targeted prompts. Learners reported breaking tasks into smaller steps, testing partial solutions, and sometimes comparing two approaches before submission.

S3: “It kept asking, ‘what do you want your code to do?’ so I wrote my plan in steps. Then the tips matched my plan, and I could try another way too.”

S10: “I started to code a little, run it, and then add more. The ChatGPT said to catch errors early, and that made me less scared of big crashes.”

Students moved from unguided trial-and-error toward stepwise reasoning and selective exploration of alternatives.

4.1.3. Personalized Support for Struggling Students

Learners who progressed more slowly reported that Study Mode helped by suggesting simplified versions first, plus short checklists (e.g., re-initializing variables). This approach produced small wins that stabilized progress.

S5: “ChatGPT told me, ‘just make it pick up one gem first.’ I did that and felt okay. Then it said, ‘now add the if part.’ Doing it bit by bit was not so scary.”

S9: “Chatbot reminded me, ‘reset your counter’ and I was like, oh yeah, I always forget that. After that I made a little list so I would not mess up the same way.”

These reports indicate individualized scaffolds that matched students’ current state and supported incremental mastery.

4.1.4. Arena Tasks and Knowledge Transfer

Several students recombined code patterns from earlier levels into reusable “skeletons” (e.g., patrol, collect, engage) in the arena competition. They attributed modular organization to prior Study Mode nudges (e.g., defining helper functions, naming steps).

S1: “I reused the collect part from before and the guard part from another level. I made a function for each, then put them together. It felt like building with pieces I already knew.”

S8: “We asked ChatGPT for ideas to defend, and it said patrolling. We tried that, and it worked better when we put it with our coin code.”

These situations suggest transferring patterns and organizational habits from guided practice to an open-ended task.

4.2. RQ2: Learning Motivation

4.2.1. Enhancing Student Engagement

Gamified progression kept students interested, while ChatGPT’s Study Mode reduced waiting time and frustration. The combined effect was more time spent on tasks in class and voluntary practice at home.

S2: “If I were bored before, I would stop. But here the game is fun, and if I get stuck I ask the bot. I tried more times and did extra levels at home.”

S4: “There was always something to do. If I could not finish, I would ask ChatGPT to learn more after dinner, and then I would keep going.”

Students linked ongoing engagement to instant support and visible progress cues.

4.2.2. “Always-Available” Learning Tutor

Students valued being able to continue learning outside school hours. The ability to resolve issues the same day prevented week-long stalls and lowered anxiety.

S4: “I did not have to wait till the next class. I asked the chatbot on Wednesday night and fixed it, so I was not worrying till Friday.”

S1: “It is like having a teacher all the time. If I get an idea from ChatGPT at night, I can try it and get a hint right away.”

On-demand access supported continuity and self-paced practice, which students perceived as motivating.

4.2.3. Emotional Support

The chatbot’s calm tone and reassuring language helped students manage frustration during errors and the arena’s time pressure. Students described feeling safer to try again.

S9: “I felt it was hard in the tournament. The chatbot said, ‘take a breath, let us check step by step,’ and that made me calmer. I fixed my loop and felt proud.”

S8: “It said, ‘lots of people find this hard in Programming,’ so I did not feel dumb. Then I tried again and it worked.”

A supportive dialogue style appeared to reduce negative affect that can derail persistence.

4.2.4. Motivation and Self-Efficacy

As students succeeded with guided hints, many reported a stronger belief in their ability to code. Mastery experiences during more challenging levels and the arena were cited as turning points.

S6: “At first I thought I would never do the hard levels. After fixing many bugs with the bot, errors felt normal. When my arena code worked, I thought, okay, I can do this.”

S2: “Finishing the whole track made me feel like a real coder. The chatbot helped, but I still wrote it and felt proud.”

Students framed success as their own, with Study Mode acting as a coach rather than a substitute, which aligns with higher self-efficacy.

4.3. RQ3: Self-Regulated Learning

4.3.1. Strengthening SRL

Students reported clearer goals for each session and more consistent progress monitoring. Study Mode contributed in three concrete ways.

First, because it does not provide complete solutions, students learned that they needed to state a near-term goal and current context to get useful hints; otherwise the chatbot replied with clarifying probes (for example, “What are you trying to make your hero do?” or “What did you try?”).

Second, the hint format typically asked them to make a small change and report the result, which operationalized progress monitoring in short cycles.

Third, repeated clarifications about names, loop stops, and variable states effectively became a pre-flight checklist students internalized over time. The teacher’s modeling at the start of class made this visible, but the repeated turns with Study Mode sustained the habit.

S8: “Our teacher said to set a mini-goal. I wrote ‘finish the level and fix my loop.’ When I asked the chatbot, it said what I wanted my hero to do, so I typed my goal and the bug. That kept me on track.”

S4: “Before I asked, I checked my little list: did I name it right, did the loop stop, and did I reset stuff? ChatGPT always asked those things, so I started asking myself first.”

The interaction contract of Study Mode (no direct answers, ask-for-context, hint-then-test) reinforced goal articulation, self-checking, and monitoring—all core SRL behaviors—while teacher modeling jump-started the routine.

4.3.2. Personalized and Adaptive Learning Support

Adaptive hints nudged faster learners to try alternate strategies, while slower learners adopted “small test first” routines. Both groups described adjusting pace and strategy more deliberately.

S1: “When I finished quickly, it dared me to solve it a different way. I tried without if statements once, just to see, and learned more.”

S5: “I now do the easy part first, run it, and then add the hard part. If it breaks, I know where to look.”

These patterns indicate emerging control over strategy selection and task granularity.

4.3.3. Facilitation of Collaborative Learning

Ahead of the capstone, students entered the multiplayer arena (Wakka Maul), where each learner chose Red or Blue team and submitted code to control a hero. The system automatically matched Red vs. Blue programs, ran head-to-head battles, and updated a real-time leaderboard. Pairs on the same team sometimes co-designed strategies, using Study Mode to settle disagreements (e.g., patrol vs. camp), align terms (“patrol loop,” “chase range,” “priority target”), and then immediately test the advice by queueing new matches.

S6: “We were Blue team and argued about patrolling or just guarding gems. We asked the chatbot, and it said to try a patrol first and check the nearest gem. We changed it and went up on the board.”

S2: “I was Red and my friend too. Our hero chased too far and got hit. We asked how to stop chasing. It said to add a distance check. After we fixed it, I moved up three places.”

In this setting, the chatbot acted as a neutral mediator and shared reference, while the arena’s auto-matches and leaderboard provided rapid feedback. Together, they supported co-regulation: teams converged on clearer plans, common vocabulary, and quicker iteration.

4.3.4. Emergence of Self-Generated Question Scripts

By week three, several students had adopted structured prompts that included context, current behavior, and a hint request only. This improved the relevance of responses and reduced back-and-forth.

S1: “If I said, ‘I want X, my code does Y, stuck at Z, give three hints,’ I got better advice every time. I told my friends to ask like that.”

S3: “Saying what I tried made the tips match me. I use the same format now, so it is faster.”

Students solved problems and optimized their interaction with the tool, which is a meta-level SRL skill.

5. Conclusion

This study explored how combining CodeCombat with ChatGPT’s GPT-5 Study Mode—delivered through the “Study and Learn” interface—impacted the learning experience of grade 5–6 Python novices over three weeks. The findings show that the hint-first, context-requiring design of Study Mode played a central role in shaping students’ learning achievement, motivation, and self-regulated learning.

For RQ1 (Learning Achievement), Study Mode supported a rapid try–feedback–revise cycle in which hints targeted specific error types such as variable name mismatches, loop stop conditions, and missed variable resets. This guidance shifted students from unguided trial-and-error to stepwise planning with small tests. Struggling learners benefited from simplified minimum-viable goals and short checklists that stabilized progress, while faster learners were prompted to modularize patterns in basic syntax, loops, and variables. Several of these modularized code “skeletons” were successfully transferred to the multiplayer arena, where students recombined and tuned them for competitive play, demonstrating functional knowledge transfer.

For RQ2 (Learning Motivation), the gamified progression of CodeCombat combined with Study Mode’s instant, on-demand support reduced idle waiting and frustration, keeping students engaged during class and encouraging voluntary practice at home. The “always-available” nature of Study Mode allowed learners to solve problems outside class hours, preventing multi-day stalls and maintaining continuity. Its calm and supportive tone helped students manage frustration in error-heavy moments and during the arena’s time pressure. As they overcame challenges with guided hints, students credited success to their efforts, aligning with increased self-efficacy and sustained motivation.

For RQ3 (Self-Regulated Learning), the “Study and Learn” design required students to specify goals and provide context before receiving hints, reinforcing short-term goal setting and active progress monitoring. The repeated focus on naming, loop stops, and variable states evolved into internalized pre-flight checklists, while the hint–test–revise routine operationalized self-checking in short cycles. In the arena, Study Mode mediated team discussions, helped align coding vocabulary, and encouraged rapid strategy adjustments based on leaderboard feedback. By week three, several students had developed structured “question scripts” containing context, current behavior, and a request for hints only, showing early adoption of independent help-seeking and regulation strategies.

Overall, GPT-5’s Study Mode in “Study and Learn” format was a coach that maintained learner responsibility for solutions while enabling continuous progress through guided dialogue. It helped students debug and reason about code, fostered transferable programming patterns, kept them engaged, and supported the development of foundational self-regulation habits. When embedded in a game-based coding sequence and coupled with clear classroom modeling, this approach offers a practical pathway for using AI tutoring to strengthen cognitive and metacognitive skills in young programming learners.

6. Limitations

This work has limits. It was relatively short in duration and relied on a single class. Access to later paid content varied by pace, and we did not compute causal effects. The patterns we report are descriptive and should be validated with mixed-methods designs.

Future studies should extend the timeline, combine qualitative tracing with objective indicators of progress, and, with consent, link dialogue turns to code edits and arena results. Comparing stricter versus looser “no direct answers” settings, or contrasting Study Mode with alternative tutoring designs, would help isolate the mechanisms that matter most. It will also be valuable to examine differences by prior interest and home access, and to track teacher orchestration over a longer term.

References

- W. C. Choi, I. C. Choi, and C. I. Chang, ‘The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Education: The Applications, Advantages, Challenges and Researchers’ Perspective’, Preprints, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang and W. Fan, ‘The effect of ChatGPT on students’ learning performance, learning perception, and higher-order thinking: insights from a meta-analysis’, Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–21, 2025.

- C. I. Chang, W. C. Choi, and I. C. Choi, ‘Challenges and Limitations of Using Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) with ChatGPT in Programming Curriculum: A Systematic Literature Review’, in Proceedings of the 2024 7th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, 2024. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI, ‘Introducing GPT-5’. [Online]. Available: https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5/.

- W. C. Choi and C. I. Chang, ‘ChatGPT-5 in Education: New Capabilities and Opportunities for Teaching and Learning’, Preprints, Aug. 2025.

- OpenAI, ‘Introducing Study Mode’. [Online]. Available: https://openai.com/index/chatgpt-study-mode/.

- W. C. Choi and C. I. Chang, ‘What is Study Mode in GPT-5: Ways to Use AI-based Chatbot (ChatGPT) as Learning Tutors in Education’, Preprints, Aug. 2025.

- M. Tedesco, ‘ChatGPT will launch new study mode for students’. [Online]. Available: https://mynbc15.com/news/nation-world/chatgpt-launch-new-study-mode-students-artificial-intelligence-college-work-office-hours.

- J. Rowsell, ‘ChatGPT “study mode” feature aims to encourage critical thinking’. [Online]. Available: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/chatgpt-study-mode-feature-aims-encourage-critical-thinking.

- C. Kroustalli and S. Xinogalos, ‘Studying the effects of teaching programming to lower secondary school students with a serious game: a case study with Python and CodeCombat’, Educ. Inf. Technol., vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 6069–6095, 2021.

- Z. Liu, H. Zuo, and Y. Lu, ‘The Impact of ChatGPT on Students’ Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis’, J. Comput. Assist. Learn., vol. 41, no. 4, p. e70096, 2025.

- W. C. Choi, J. Peng, I. C. Choi, H. Lei, L. C. Lam, and C. I. Chang, ‘Improving Young Learners with Copilot: The Influence of Large Language Models (LLMs) on Cognitive Load and Self-Efficacy in K-12 Programming Education’, in Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE), Suzhou, China, 2025.

- Y.-L. E. Liu, T.-P. Lee, and Y.-M. Huang, ‘Enhancing student engagement and higher-order thinking in human-centred design projects: the impact of generative AI-enhanced collaborative whiteboards’, Interact. Learn. Environ., pp. 1–18, 2025.

- H.-Y. Lee and T.-T. Wu, ‘Enhancing Blended Learning Discussions with a Scaffolded Knowledge Integration–Based ChatGPT Mobile Instant Messaging System’, Comput. Educ., p. 105375, 2025.

- G. Jošt, V. Taneski, and S. Karakatič, ‘The impact of large language models on programming education and student learning outcomes’, Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 10, p. 4115, 2024.

- C. I. Chang, W. C. Choi, I. C. Choi, and H. Lei, ‘A Systematic Literature Review of the Practical Applications of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content (AIGC) Using OpenAI ChatGPT, Copilot, and Codex in Programming Education’, in Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Education and E-Learning, 2024.

- S. Küchemann et al., ‘On opportunities and challenges of large multimodal foundation models in education’, Npj Sci. Learn., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 11, 2025.

- Y. M. E. Heung and T. K. Chiu, ‘How ChatGPT impacts student engagement from a systematic review and meta-analysis study’, Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell., vol. 8, p. 100361, 2025.

- Q. Xia, W. Li, Y. Yang, X. Weng, and T. K. F. Chiu, ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) on students’ motivation and engagement’, Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell., vol. 9, p. 100455, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Hasanein and A. E. E. Sobaih, ‘Drivers and consequences of ChatGPT use in higher education: Key stakeholder perspectives’, Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ., vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 2599–2614, 2023.

- H.-Y. Lee, P.-H. Chen, W.-S. Wang, Y.-M. Huang, and T.-T. Wu, ‘Empowering ChatGPT with guidance mechanism in blended learning: Effect of self-regulated learning, higher-order thinking skills, and knowledge construction’, Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 16, 2024.

- D. T. K. Ng, C. W. Tan, and J. K. L. Leung, ‘Empowering student self-regulated learning and science education through ChatGPT: A pioneering pilot study’, Br. J. Educ. Technol., vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 1328–1353, 2024.

- CodeCombat, ‘Introduction to Codecombat CS1 — Lesson Plans’. [Online]. Available: https://codecombat.com/teachers/resources/cs1.

- K. Charmaz, Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. sage, 2006.

- J. Corbin and A. Strauss, Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).