Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

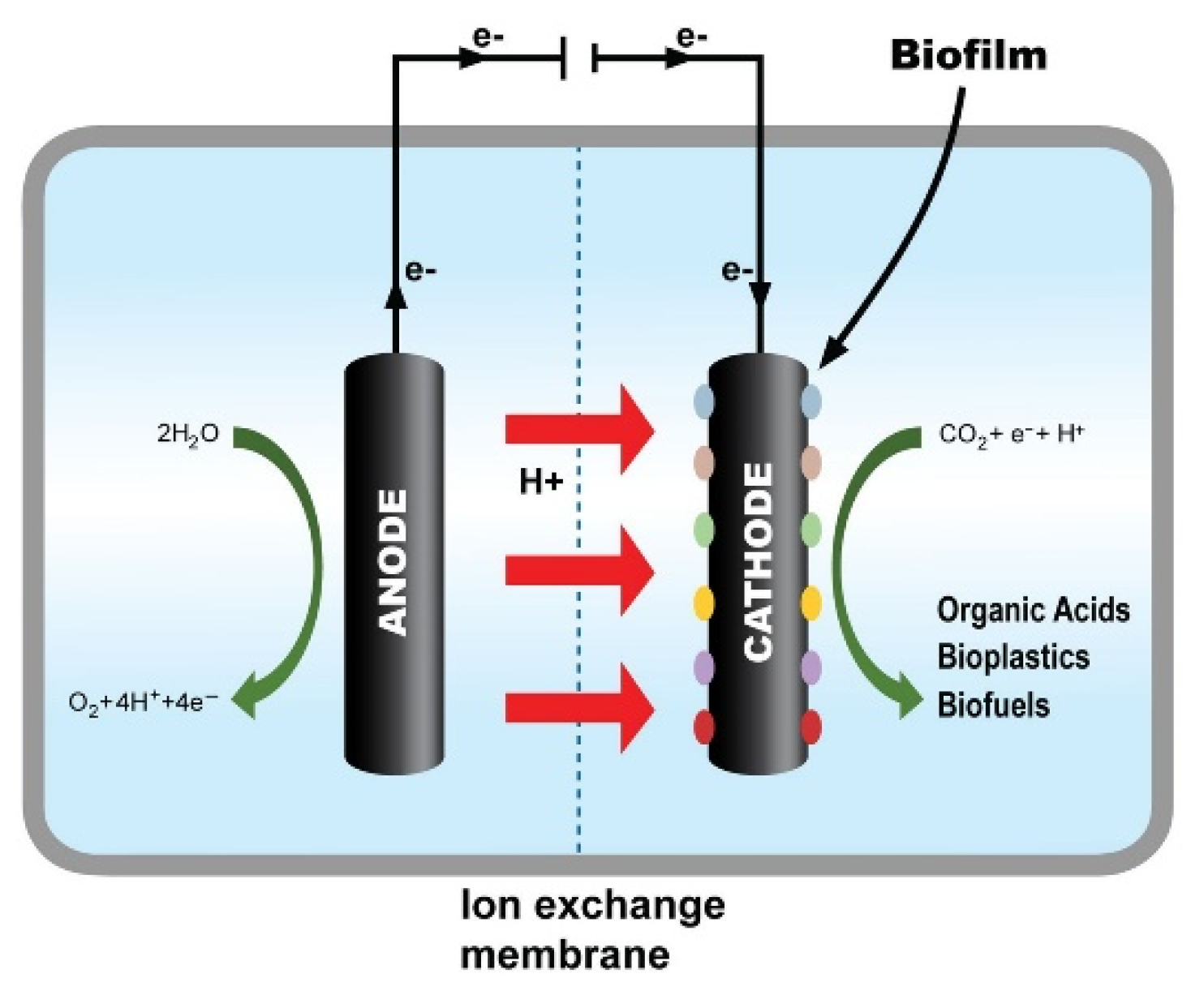

- Electrode–microbe electron transfer. Electrons originate at a cathode (driven by an external power source, preferably renewables). Electron transfer mechanisms include (a) direct extracellular electron transfer (EET) via conductive biofilms or redox proteins, and (b) indirect hydrogen-mediated transfer, wherein electrochemically produced H₂ is consumed by hydrogenotrophic acetogens. Distinguishing between these pathways remains a major experimental and conceptual theme across 2010–2025 studies [1,4].

- Electro-trophic metabolism. Many acetogens (e.g., Sporomusa, Acetobacterium, Clostridium) deploy the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway to fix CO₂ to acetyl-CoA and then excrete acetate or reduce further to ethanol/butanol under specified conditions. Advances in metabolic understanding and synthetic biology approaches to expand product scope have intensified after 2020 [5,6].

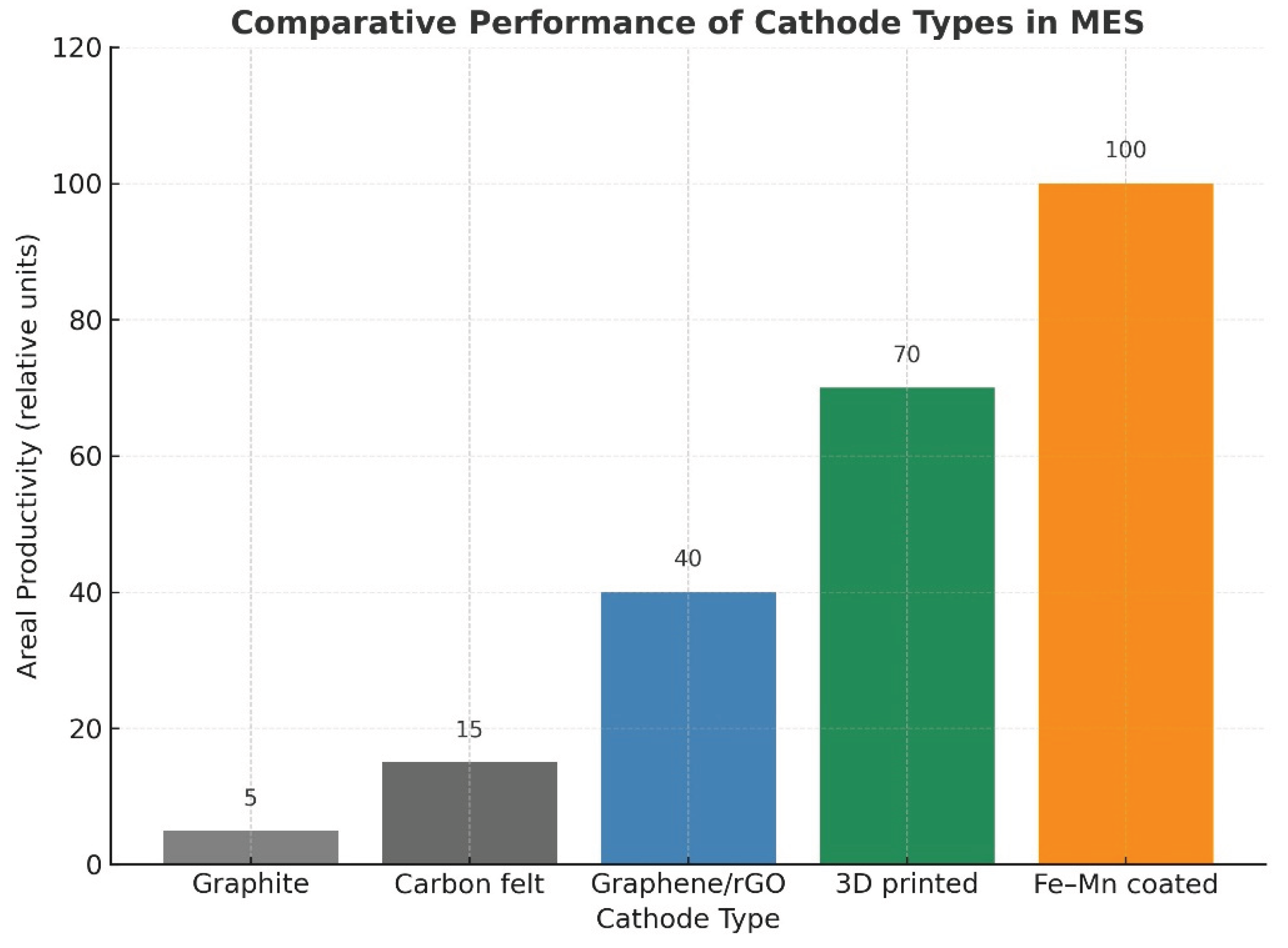

- System design. Reactor architecture, cathode material and geometry, operational potential, pH, mass transfer and anode chemistry jointly determine rates, titers and selectivity. From the initial graphite electrodes (2010) to engineered 3-D printed cathodes, materials and reactor choices have been central to MES progress [1,7].

2. Evolution of Electrode Materials for Microbial Electrosynthesis

2.1. Carbonaceous Materials and Graphene-Based Electrodes

2.1.1. Advantages and Disadvantages on Using Carbonaceous and Graphene-Based Electrodes in MES

- Carbonaceous electrodes (graphite, felt, RVC, paper): Low cost, scalable, chemically stable, and relatively easy to modify.

- Graphene-based electrodes: Outstanding conductivity, hierarchical porosity, tunable surface chemistry, and superior performance in terms of electron transfer and product selectivity.

- Circular-carbon electrodes: Sustainable, low-cost, derived from biomass or waste; high porosity and surface functionalization enable strong microbial adhesion and long-term durability.

- Plain carbon electrodes: Limited conductivity compared to advanced materials; poor catalytic activity toward hydrogen evolution, requiring high applied potentials.

- Graphene-based: High cost of synthesis, difficulties in large-scale and reproducible fabrication, and potential instability under prolonged operation.

- Circular carbons: High variability in structure and performance depending on feedstock and processing conditions; often lower conductivity than engineered graphene-based.

2.1.2. Gaps and Challenges on Using Carbonaceous and Graphene-Based Electrodes in MES

2.1.3. Future Perspectives on Using Carbonaceous and Graphene-Based Electrodes in MES

- Hybrid electrodes: Combining biochar/circular carbons with thin graphene or catalytic skins may achieve both cost-effectiveness and high performance.

- Scalable manufacturing: Techniques such as 3D printing and roll-to-roll coating can bridge lab innovation with industrial feasibility.

- Functionalized surfaces: Rational tuning of oxygen groups, nitrogen doping, or heteroatom functionalization could steer microbial adhesion and selectivity.

- Integration with techno-economics: Future studies should assess not only performance metrics (current density, coulombic efficiency) but also life-cycle impacts and cost per unit product.

| Electrode Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Gaps/Challenges | Future Perspectives |

| Carbonaceous (graphite, felt, paper, RVC) | - Low cost, abundant, scalable- Chemically stable- High surface roughness → good biofilm attachment- Easy to modify with catalysts | - Limited conductivity- Low intrinsic catalytic activity (HER)- Require high applied potentials | - Need improved catalytic function- Limited long-term durability data- Scaling issues for high productivity | - Surface functionalization (doping, coatings)- Integration with conductive polymers- Engineering 3D structured carbons |

| Graphene-based (rGO, aerogels, composites) | - Exceptional conductivity- Hierarchical porosity improves mass transfer- Tunable chemistry (functional groups)- Enhanced electron transfer & product selectivity | - High synthesis cost- Scale-up remains difficult- Potential instability during long-term runs | - Lack of standardized fabrication methods- Limited understanding of graphene–microbe interactions- Reproducibility concerns across labs | - Hybrid electrodes (graphene + biochar)- Roll-to-roll or scalable coating methods- Use in advanced 3D printed cathodes |

| Circular carbons (biochar, waste-derived) | - Sustainable & low-cost- Derived from biomass or waste (circular economy)- High porosity & wettability- Comparable biofilm colonization to graphene | - Variability in properties (feedstock dependent)- Often lower conductivity than graphene- Inconsistent performance across studies | - Lack of standardization in feedstock processing- Limited comparative benchmarks with engineered electrodes | - Standardized production methods- Hybridization with conductive nanomaterials- Scalable sustainable electrodes for industrial MES |

2.2. Composite Electrodes (Carbon + Polymers/Metals/Catalysts)

2.2.1. Advantages and Disadvantages on Using Composite Electrodes

- 3D printed carbon lattices (Ni/Mo-modified): Their engineered porosity and topology provide enhanced mass transfer and fine-tuned H₂ delivery to microbial biofilms. Studies show significantly increased volumetric productivities, particularly for acetate, due to the localized control of hydrogen flux near acetogens [Jourdin et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2024].

- Conductive polymer composites (poly-pyrrole, polyaniline, conductive PLA/ABS): These materials are low-cost, easily manufacturable, and mechanically flexible, enabling scalable electrode designs. Polymers also offer a tunable surface chemistry that supports microbial adhesion. Hybrid polymer-metal composites have reported stable long-term operation for acetate and methane production [19,21,25].

- Catalyst-assisted cathodes (Ni, Cu, Fe, Co, Mo, perovskites): The incorporation of catalytic coatings lowers HER (hydrogen evolution reaction) overpotentials and provides a controlled, microbe-friendly H₂ flux, avoiding damaging local alkalinization. This leads to higher coulombic efficiencies and improved selectivity toward acetate and other reduced compounds [14,19,20,21].

- 3D printed lattices require specialized manufacturing and may suffer from structural brittleness after prolonged use.

- Conductive polymers often face trade-offs between electrical conductivity and mechanical stability; their long-term bio-compatibility in harsh electrochemical environments is still under debate.

- Metal catalysts risk ion leaching, which can be toxic to microbial communities, and can increase system costs.

2.2.2. Gaps and Challenges on Using Composite Electrodes

2.2.3. Future Perspectives on Using Composite Electrodes

- Hybrid electrodes: Combining biochar or other circular carbons with thin catalytic coatings (Ni, Fe, Co) to balance performance and cost.

- Advanced manufacturing: Adoption of 3D printing, laser etching, and roll-to-roll coating for scalable, reproducible electrodes.

- Eco-friendly catalysts: Replacement of noble or heavy metals with earth-abundant, biodegradable alternatives (e.g., Fe- or Mn-based composites).

- Integrated techno-economic analysis: Studies should pair electrode innovations with LCA (life-cycle assessment) and cost modeling to assess true scalability.

| Composite Electrode Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Gaps/Challenges | Future Perspectives |

| 3D Printed Carbon Lattices (Ni/Mo, doped carbons) | - Tailored 3D geometry for high surface area & mass transfer- Enhanced localized H₂ delivery to biofilms- High productivities for acetate & other products | - Requires specialized equipment- Mechanical brittleness under long-term use- Fabrication costs still high | - Limited durability testing (>1000 h)- Lack of standard print protocols- Scale-up feasibility unproven | - Scale-up via industrial 3D printing- Hybridization with low-cost biochars- Integration into modular reactor stacks |

| Conductive Polymers (poly-pyrrole, polyaniline, PLA/ABS blends) | - Low-cost & lightweight- Flexible, scalable manufacturing- Tunable chemistry enhances microbial adhesion- Good long-term stability in some studies | - Moderate conductivity compared to metals- Mechanical degradation in harsh electrochemical environments- Potential bio-compatibility concerns | - Limited reproducibility between labs- Unknown long-term chemical resistance- Need more data on polymer–biofilm interactions | - Polymer-metal or polymer-carbon hybrids- Development of biodegradable conductive polymers- Use in flexible/portable MES reactors |

| Catalyst-Coated Cathodes (Ni, Fe, Cu, Co, Mo, perovskites) | - Lower HER overpotentials- Controlled H₂ flux prevents pH shocks- Increased coulombic efficiency and selectivity | - Risk of metal ion leaching (microbial toxicity)- Added costs (especially noble/perovskite catalysts)- Complex synthesis routes | - Few studies on biofilm community shifts under catalysts- Insufficient life-cycle & cost analyses- Variability in coating adhesion & durability | - Earth-abundant catalysts (Fe, Mn)- Thin catalytic coatings over low-cost supports- Techno-economic integration with renewable energy systems |

2.3. Bimetallic Oxide Cathodes

2.3.1. Advantages and Disadvantages on Using Bimetallic Oxide Cathodes

- Synergistic catalysis: Combining two or more metals enhances electron transfer kinetics and lowers overpotentials compared to monometallic oxides.

- Abundance and sustainability: Many BMOs (Fe, Mn, Ni-based) are earth-abundant, low-cost, and environmentally benign compared to noble metals.

- Enhanced biofilm performance: Oxide surfaces offer hydrophilicity, tunable porosity, and surface oxygen groups that promote microbial adhesion and stable electro-trophic growth.

- Selectivity: BMOs can regulate H₂ evolution to match microbial uptake rates, avoiding accumulation and energy losses.

- Conductivity issues: Many oxides have lower intrinsic conductivity compared to carbon or graphene, requiring support materials or dopants.

- Metal leaching: Prolonged use may release ions (e.g., Ni²⁺, Co²⁺), potentially toxic to microbial communities.

- Complex synthesis: Hydrothermal, sol-gel, or electrodeposition methods can be costly and difficult to scale.

- Variability: Performance is highly dependent on metal ratios, synthesis conditions, and electrode architecture.

2.3.2. Gaps and Challenges on Using Bimetallic Oxide Cathodes

2.3.3. Future Perspectives on Using Bimetallic Oxide Cathodes

- Low-cost synthesis: Emphasis on scalable, eco-friendly methods (e.g., electrodeposition on felts, waste-derived metal oxides).

- Hybrid electrodes: Combination of BMOs with graphene or biochar supports to overcome conductivity limitations.

- Mechanistic studies: In situ spectroscopy and omics approaches could resolve how BMOs interact with electro-trophic consortia.

- Circular economy approaches: Utilizing waste streams (steel slag, mine tailings) as oxide precursors to reduce costs.

| Electrode Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Gaps/Challenges | Future Perspectives |

| Biometallic Oxides (Fe–Mn, Ni–Co, Cu–Fe, perovskites) | - Synergistic catalytic activity- Earth-abundant, low-cost metals- Hydrophilic, biofilm-friendly surfaces- Tunable HER selectivity | - Low intrinsic conductivity- Risk of metal ion leaching (toxicity)- Complex & costly synthesis- Performance highly condition-dependent | - Limited long-term stability data- Lack of standardized testing- Poor understanding of electron transfer mechanisms- Few techno-economic studies | - Hybrid electrodes with carbon/graphene supports- Scalable electrodeposition or waste-derived oxides- Mechanistic in situ studies- Integration with circular economy feedstocks |

2.4. Cross-Cutting Insights on the Development of MES Electrodes as Resulting from 2010–2025 Literature

3. Evolution of Microbial Communities and Biofilm Engineering

3.1. Carbonaceous Materials & Graphene

3.2. Composite Electrodes

3.3. Bi-Metallic Oxides (BMOs)

3.4. Gaps and Challenges on Co-Shape Communities

3.5. Future Perspectives on Biofilm Engineering

4. Evolution of Reactor Configurations and Process Engineering

4.1. Carbonaceous & Graphene Cathodes: Surface Area, Gas Handling, and GDEs

4.2. Composite Electrodes: Engineering the H₂ Micro-Niche

4.3. Bimetallic Oxides: Low-Overpotential HER and Biofilm Compatibility

4.4. Scale-Up Lessons: Hydrodynamics, Compartmentalization, and Control

4.5. Gaps & Limitations on Reactor Configurations and Process Engineering

4.6. Future Perspectives on Reactor Configurations and Process Engineering

5. Performance Trends and Techno-Economic Signals

5.1. Performance Trends

5.2. Techno-Economic Signals

6. Conclusions

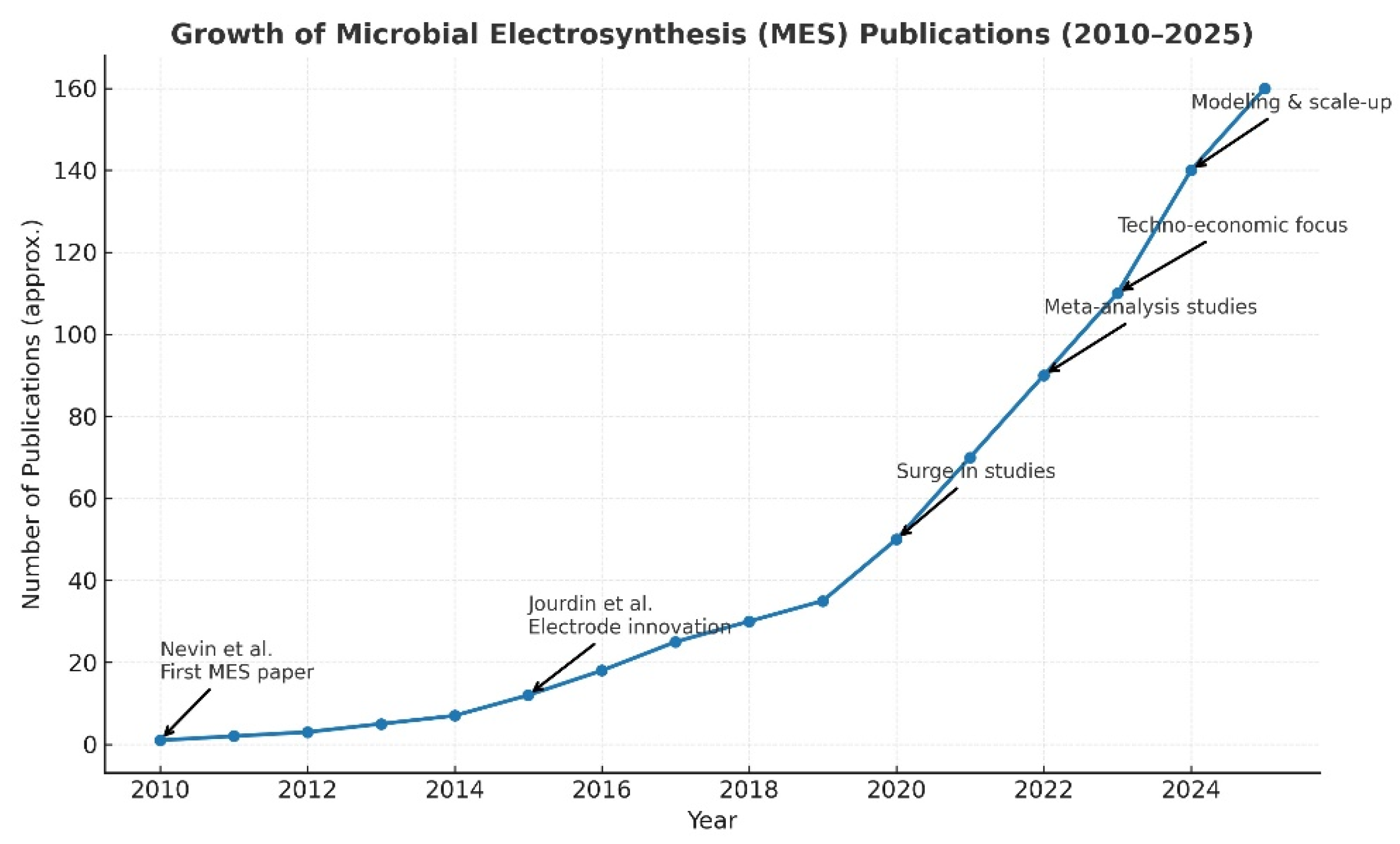

- Microbial electrosynthesis (MES) has progressed remarkably since its inception, moving from proof-of-concept studies in H-type reactors toward increasingly sophisticated systems that integrate novel electrode materials, microbial community engineering, and process optimization. The literature consistently highlights that electrode design and material innovation—ranging from carbonaceous substrates and graphene-based coatings to composite cathodes and biometallic oxides—are central drivers of improved performance, as they directly impact electron transfer efficiency, biofilm formation, and hydrogen evolution dynamics.

- Parallel to these advances, microbial community engineering has transitioned from reliance on mixed consortia to more controlled and, in some cases, genetically optimized strains, offering opportunities to fine-tune product selectivity and stability. Similarly, reactor configurations have evolved from simple two-chamber setups to plate, tubular, and zero-gap flow designs, significantly reducing ohmic losses and improving mass transfer.

- Despite these advances, several challenges remain. MES still faces critical barriers to scale-up, including insufficient long-term stability, hydrogen management inefficiencies, incomplete understanding of microbe–electrode interactions, and economic constraints tied to electricity demand and reactor capital costs. Current techno-economic assessments emphasize the need for higher current densities, improved Faradaic efficiencies, and durable low-cost materials to render MES competitive with conventional biotechnologies and power-to-X alternatives.

- Looking forward, the field is poised to benefit from integrative approaches—combining advanced material science, systems biology, and process engineering with data-driven modeling and techno-economic analysis. In particular, hybrid electrode architectures (graphene–oxide composites, catalytic coatings), biofilm engineering strategies, and intensified flow-through reactor designs hold promise for achieving the productivity thresholds required for industrial relevance. Furthermore, the alignment of MES research with renewable electricity integration and CO₂ circular economy initiatives underscores its potential role in decarbonization strategies.

- In conclusion, while MES is not yet a mature industrial technology, the trajectory of scientific progress between 2010 and 2025 signals a growing momentum toward practical application. Success will depend on bridging laboratory innovations with scalable, robust, and economically viable process configurations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K.P. Nevin, T.L. Woodward, A.E. Franks, Z.M. Summers, D.R. Lovley “Microbial Electrosynthesis: Feeding Microbes Electricity To Convert Carbon Dioxide and Water to Multicarbon Extracellular Organic Compounds”, ASM Journals, 2010, vol. 1, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- Jourdin, L.; Grieger, T.; Monetti, J.; Flexer, V.; Freguia, S.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Romano, M.; Wallace, G.G.; Keller, J. High Acetic Acid Production Rate Obtained by Microbial Electrosynthesis from Carbon Dioxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13566–13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Salehmin, M.N.I.; Balachandran, K.; Me, M.F.H.; Loh, K.S.; Abu Bakar, M.H.; Jong, B.C.; Lim, S.S. Role of microbial electrosynthesis system in CO2 capture and conversion: a recent advancement toward cathode development. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1192187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. Regulatory Mechanisms of Electron Supply Modes for Acetate Production in Microbial Electrosynthesis System. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 4406–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnisch, F.; Deutzmann, J.S.; Boto, S.T.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Microbial electrosynthesis: opportunities for microbial pure cultures. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Foo, J.L.; Chang, M.W. Microbial electrosynthesis meets synthetic biology: Bioproduction from waste feedstocks. Biotechnol. Notes 2025, 6, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, G.S.; Bazaka, K.; Ramakrishna, S.; Kumaravel, V. Microbial electrosynthesis: carbonaceous electrode materials for CO2 conversion. Mater. Horizons 2022, 10, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamun, A.; Ahmed, W.; Jafary, T.; Nayak, J.K.; Al-Nuaimi, A.; Sana, A. Recent advances in microbial electrosynthesis system: Metabolic investigation and process optimization. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; Dessì, P.; Pant, D.; Farràs, P.; Sloan, W.T.; Collins, G.; Ijaz, U.Z. A meta-analysis of acetogenic and methanogenic microbiomes in microbial electrosynthesis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.D.; Clark, D.S. Techno-Economic Assessment of Electromicrobial Production of n-Butanol from Air-Captured CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 7302–7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.; Moon, M.; Park, G.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.Y. Evaluation of economic feasibility for the microbial electrosynthesis-based β-farnesene production technology: Process modeling and techno-economic assessment. J. CO2 Util. 2025, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdin, L.; Freguia, S.; Flexer, V.; Keller, J. Bringing High-Rate, CO2-Based Microbial Electrosynthesis Closer to Practical Implementation through Improved Electrode Design and Operating Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Cobo, M.F.-A.; Zeng, D.; Zhang, Y. Leveraging 3D printing in microbial electrochemistry research: current progress and future opportunities. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Sun, D.; Hu, Z.; Li, P.; Xu, H.; Wu, H.; Qiu, B.; et al. Effect of different hydrogen evolution rates at cathode on bioelectrochemical reduction of CO2 to acetate. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 913, 169744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, L. Cathode catalyst-assisted microbial electrosynthesis of acetate from carbon dioxide: promising material selection. J. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liang, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, B.; Li, X.-Y.; Lin, L. Boosting Microbial CO2 Electroreduction by the Biocompatible and Electroactive Bimetallic Fe–Mn Oxide Cathode for Acetate Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 15659–15670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.H.; Rahman, A.; Chakrabarty, A.A.; Zakaria, B.S.; Khondoker, M.A.H.; Dhar, B.R. 3D printed cathodes for microbial electrolysis cell-assisted anaerobic digester: Evaluation of performance, resilience, and fluid dynamics. J. Power Sources 2024, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, N.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Chang, J.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, R.J. Flow-Electrode Microbial Electrosynthesis for Increasing Production Rates and Lowering Energy Consumption. Engineering 2023, 25, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, R.; Vidales, A.G.; Omanovic, S.; Tartakovsky, B. Mathematical model of a microbial electrosynthesis cell for the conversion of carbon dioxide into methane and acetate. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.W.; Ross, D.E.; Fichot, E.B.; Norman, R.S.; May, H.D. Long-term Operation of Microbial Electrosynthesis Systems Improves Acetate Production by Autotrophic Microbiomes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6023–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengsbach, J.-N.; Sabel-Becker, B.; Ulber, R.; Holtmann, D. Microbial electrosynthesis of methane and acetate—comparison of pure and mixed cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 4427–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.F.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Qin, H.Y. A short review of graphene in the microbial electrosynthesis of biochemicals from carbon dioxide. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22770–22782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, H. Enhanced microbial electrosynthesis performance with 3-D algal electrodes under high CO2 sparging: Superior biofilm stability and biocathode-plankton interactions. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 412, 131381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kracke, F.; Deutzmann, J.S.; Jayathilake, B.S.; Pang, S.H.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Baker, S.E.; Spormann, A.M. Efficient Hydrogen Delivery for Microbial Electrosynthesis via 3D-Printed Cathodes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 696473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanebu, E.; Omanovic, S.; Hrapovic, S.; Vidales, A.G.; Tartakovsky, B. Carbon dioxide conversion to acetate and methane in a microbial electrosynthesis cell employing an electrically-conductive polymer cathode modified by nickel-based coatings. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, L. Cathode catalyst-assisted microbial electrosynthesis of acetate from carbon dioxide: promising material selection. J. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; He, J.; Huang, H.; Song, T.-S.; Wu, X.; Xie, J.; Zhou, W. Perovskite-Based Multifunctional Cathode with Simultaneous Supplementation of Substrates and Electrons for Enhanced Microbial Electrosynthesis of Organics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 30449–30456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadi, P.; Fontmorin, J.-M.; Godain, A.; Yu, E.H.; Head, I.M. Parameters influencing the development of highly conductive and efficient biofilm during microbial electrosynthesis: the importance of applied potential and inorganic carbon source. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Peña, D.; Mateos, R.; Morán, A.; Escapa, A. Reduced graphene oxide improves the performance of a methanogenic biocathode. Fuel 2022, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Ding, S.; Song, B.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, J.-J. Cathode materials in microbial electrosynthesis systems for carbon dioxide reduction: recent progress and perspectives. Energy Mater. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Dong, Z.; Huang, Q.; Song, T.-S.; Xie, J. Fe3O4/granular activated carbon as an efficient three-dimensional electrode to enhance the microbial electrosynthesis of acetate from CO2. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 34095–34101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, R.; O’sHea, R.; Deng, C.; Xuan, X.; Xia, R.; Wall, D.M.; Murphy, J.D. Microbe-electrode interactions on biocathodes are facilitated through tip-enhanced electric fields during CO2-fed microbial electrosynthesis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, B.; Yu, N.; Yun, N.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Xie, C.; Rossi, R.; Logan, B.E. Substantially Improved Microbial Electrosynthesis of Methane Achieved by Improving Hydrogen Retention and Flow Distribution through Porous Electrodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 13719–13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddings, C.G.S.; Nevin, K.P.; Woodward, T. Simplifying microbial electrosynthesis reactor design. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Xue, X.; Cai, W.; Cui, K.; Patil, S.A.; Guo, K. Recent progress on microbial electrosynthesis reactor designs and strategies to enhance the reactor performance. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutzmann, J.S.; Callander, G.; Spormann, A.M. Improved reactor design enables productivity of microbial electrosynthesis on par with classical biotechnology. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 416, 131733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, S.; Krige, A.; Matsakas, L.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Advances in cathode designs and reactor configurations of microbial electrosynthesis systems to facilitate gas electro-fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckl, M.; Lange, T.; Izadi, P.; Bolat, S.; Teetz, N.; Harnisch, F.; Holtmann, D. Application of gas diffusion electrodes in bioeconomy: An update. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Martínez, D.A.; Martínez-Amador, S.Y.; la Garza, J.A.R.-D.; Laredo-Alcalá, E.I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P. Recent Advances in Scaling up Bioelectrochemical Systems: A Review. BioTech 2025, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.; Ilankoon, I.; Zhang, Y.; Chong, M.N. Scaling up of dual-chamber microbial electrochemical systems – An appraisal using systems design approach. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 912, 169186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanebu, E.; Jezernik, M.; Lawson, C.; Bruant, G.; Tartakovsky, B. Impact of cathodic pH and bioaugmentation on acetate and CH4 production in a microbial electrosynthesis cell. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 22962–22973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohbohm, N.; Angenent, L.T. A development study for liquid- and vapor-fed anode zero-gap bioelectrolysis cells. iScience 2025, 28, 112959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabau-Peinado, O.; Winkelhorst, M.; Stroek, R.; Angelino, R.d.K.; Straathof, A.J.; Masania, K.; Daran, J.M.; Jourdin, L. Microbial electrosynthesis from CO2 reaches productivity of syngas and chain elongation fermentations. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1503–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdin, L.; Sousa, J.; van Stralen, N.; Strik, D.P. Techno-economic assessment of microbial electrosynthesis from CO2 and/or organics: An interdisciplinary roadmap towards future research and application. Appl. Energy 2020, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Leininger, A.; May, H.D.; Ren, Z.J. H2 mediated mixed culture microbial electrosynthesis for high titer acetate production from CO2. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2023, 19, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, B.; Yu, N.; Akbari, A.; Shi, L.; Zhou, X.; Xie, C.; Saikaly, P.E.; Logan, B.E. Using a non-precious metal catalyst for long-term enhancement of methane production in a zero-gap microbial electrosynthesis cell. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).