1. Introduction

The two pillars of modern physics—general relativity and quantum mechanics—mathematically rely on differential geometry and operator algebra respectively, and these mathematical tools are in turn built upon ZFC set theory. However, infinite concepts in ZFC (such as uncountable infinity and large cardinals) face fundamental difficulties in physical realization: physical measurements are always finite, discrete, and subject to error.

In recent years, theoretical physics has seen proposals to use Woodin cardinal

as a fundamental invariant in quantum gravity unification theories [

1]. In particular, Lin [

5] proposed a unified framework that treats Woodin cardinal as a holographic renormalization group invariant. However,

is defined in ZFC as a large cardinal satisfying certain "infinite embedding" properties, which contradicts the finiteness and measurability of physical constants. To resolve this contradiction, we propose

Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics (JCM), a new constructive mathematical framework designed to "finitize" and "operationalize" infinite objects.

1.1. Limitations of Existing Mathematical Systems

Classical constructive mathematics (such as Bishop’s constructive analysis [

2]) emphasizes "constructibility" and "computability", but its scope is limited to countable objects and recursive functions, unable to handle higher-order infinite concepts like large cardinals. On the other hand, non-constructive mathematics (such as ZFC) allows uncountable infinity and the axiom of choice but lacks paths to physical realization.

JCM is proposed precisely to fill this gap: it allows "simulating" infinite objects through finite operational steps, thereby providing a mathematical foundation for physical realization. The core idea of JCM is to represent infinite objects as limits of finite approximation sequences and to process these approximations through physically realizable operations.

1.2. History and Development of Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics

The naming of Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics draws inspiration from the ancient Chinese mathematical classic "Jiuzhang Suanshu" (Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art), emphasizing practicality and algorithmic thinking. The development of JCM has been inspired by multiple mathematical and physical fields:

1. Constructive mathematics (Bishop, 1967) provides the theoretical foundation for the computability of mathematical objects; 2. Computable analysis (Weihrauch, 2000) offers a framework for the computable representation of real numbers; 3. The renormalization group method in physics (Wilson, 1971) demonstrates how to handle physical systems at different scales; 4. The holographic principle (Maldacena, 1997) reveals the dual relationship between higher-dimensional gravitational theories and lower-dimensional field theories.

JCM integrates these ideas into a unified framework, particularly suited for addressing mathematical problems in quantum gravity theory.

2. Basic Framework of JCM

JCM is built upon the following three fundamental principles:

Principle 2.1

(Domain Confinement Principle)

. Any mathematical operation must be confined to a physically observable closed domain. For example, for Woodin cardinal κ, we confine it to:

where L is the AdS radius and is the Planck length.

The Domain Confinement Principle ensures that all mathematical operations occur within physically realizable ranges, avoiding the appearance of true infinity. The mathematical implementation of this principle relies on compactness arguments and finite approximation techniques.

Principle 2.2

(Operational Finitization Principle)

. Replace infinite operations with finite-step controllable processes. For example, replace the infinite embedding with:

The Operational Finitization Principle emphasizes that all mathematical operations must be completed in finite steps, with each step corresponding to a physically realizable process. The implementation of this principle relies on recursive function theory and computational complexity theory.

Principle 2.3

(Dual Isomorphism Principle)

. Establish isomorphic mappings between mathematical structures and physical phenomena. For example:

where the elementary embedding in set theory corresponds to the monodromy operator of the renormalization group (RG).

The Dual Isomorphism Principle ensures consistency between mathematical structures and physical phenomena, giving mathematical derivations clear physical interpretations. The implementation of this principle relies on category theory and homological algebra.

2.1. Mathematical Formalization of the Three Principles

The Domain Confinement Principle can be formalized as: For any mathematical object

X, there exists a finite approximation sequence

and a physically realizable domain

D such that:

The Operational Finitization Principle can be formalized as: For any mathematical operation

, there exists a finite-step algorithm

such that:

The Dual Isomorphism Principle can be formalized as: There exists a functor that preserves key structures between the mathematical category and the physical category .

3. Mathematical Foundation of JCM

3.1. Constructive Universe J

We define the universe J of JCM as a structure satisfying the following conditions:

J is a countable model;

J contains all constructible real numbers;

All functions in J are computable;

All "infinite" objects in J are represented by their finite approximations.

Definition 1

(J-Constructibility). An object x is J-constructible if there exists an algorithm that can output any finite approximation of x in finite steps.

More formally, x is J-constructible if and only if there exists a computable function such that for any , .

Remark 1.

This is similar to "constructible real numbers" in Bishop’s constructive analysis, but JCM allows more generalized "approximate constructibility", including finite representations of infinite objects. J-constructibility is more general than traditional computability as it allows finite approximations of non-recursive objects.

3.2. Representation of Real Numbers in JCM

In JCM, real numbers are represented by their finite approximations. Specifically, a real number x is represented by a triple , where: - is the main approximation function, satisfying ; - is the error bound function, providing guarantees of approximation accuracy; - is the convergence acceleration function, used to improve approximation efficiency.

This representation method allows us to obtain arbitrary precision approximations of real numbers in finite steps, while preserving the algebraic structure and topological properties of real numbers.

3.3. Woodin Cardinal in JCM

In JCM, Woodin cardinal

is no longer a true infinite cardinal but rather the limit of a

finite approximation sequence satisfying:

where

K is a scale factor related to physical constants.

Theorem 1

(Woodin Property in JCM)

. In JCM, if κ is J-constructible, then there exists a finite embedding:

such that for all , there exists satisfying:

and when , converges to the elementary embedding in ZFC.

Proof. Since is finite, is a finite set, so there exists an embedding satisfying the finite version of elementary embedding. By taking the limit, we can recover the infinite embedding in ZFC.

The detailed proof consists of three parts:

1. Existence of finite approximation: For each finite , the set is finite. Therefore, we can enumerate all functions . For each such function, we can find an ordinal such that . This can be achieved through direct construction: since is finite, we can explicitly construct such an embedding .

2.

Convergence: We need to prove that the sequence

converges to a genuine elementary embedding

. Consider any formula

and parameters

. Since

, there exists

N such that for all

,

. By the elementarity of

, we have:

When

, this gives a genuine elementary embedding

.

3. Consistency: Finally, we need to verify that this construction is consistent with the ZFC axiom system. This relies on the foundational axioms of JCM, particularly the Domain Confinement Principle and Operational Finitization Principle, ensuring that all operations occur within physically realizable ranges. □

Remark 2.

This theorem shows that the "Woodin cardinal" in JCM is actually a finite approximation of the Woodin cardinal in ZFC, thereby resolving the "infinite-finite" tension. This result has significant physical implications as it allows us to use the concept of Woodin cardinal in practical physical systems without needing to handle actual infinity.

4. Relationship between JCM and Existing Mathematical Systems

4.1. Relationship with Bishop’s Constructive Mathematics

Bishop’s constructive mathematics [

2] emphasizes "proof as algorithm" and rejects non-constructive proofs (such as the law of excluded middle and axiom of choice). JCM inherits this idea but further allows:

Finite approximations of uncountable objects;

Constructive representations of higher-order infinite concepts;

Direct correspondence with physical systems.

Therefore, JCM can be viewed as an extension of Bishop’s constructive mathematics, particularly suitable for physical modeling.

Table 1.

Comparison between Bishop’s Constructive Mathematics and JCM

Table 1.

Comparison between Bishop’s Constructive Mathematics and JCM

| Bishop’s Constructive Mathematics |

Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics (JCM) |

| Emphasizes computability and constructive proofs |

Emphasizes physical realizability and finite approximation |

| Rejects law of excluded middle and axiom of choice |

Restrictively uses axiom of choice, limited to physically realizable operations |

| Limited to countable objects and recursive functions |

Allows finite approximations of uncountable objects |

| Mainly applied to analysis and algebra |

Particularly suitable for mathematical physics and quantum gravity theory |

4.2. Relationship with ZFC

JCM is not intended to replace ZFC but rather to provide it with a "physical realization" semantics. Every infinite statement in ZFC has a corresponding finite approximation statement in JCM. For example:

Table 2.

Correspondence between ZFC Statements and JCM Approximations

Table 2.

Correspondence between ZFC Statements and JCM Approximations

| ZFC Statement |

JCM Approximation |

|

|

|

is Woodin |

is "n-Woodin" |

|

(finite approximation) |

|

|

This correspondence is guaranteed by the following theorem:

Theorem 2

(Approximation Correspondence Theorem)

. For any statement ϕ in ZFC, there exists an approximate statement in JCM such that:

and for any physically realizable domain D, we have:

Proof. The proof proceeds by induction on the structure of . The base cases involve the basic axioms of set theory, such as the axiom of extensionality, axiom of pairing, etc., which all have natural finite approximations in JCM.

For axioms involving infinity, such as the axiom of infinity and axiom of replacement, we use finite approximation sequences and limit processes to construct corresponding JCM versions.

The most critical part is the treatment of the axiom of choice. In JCM, we only allow physically realizable choice functions, i.e., there exists an algorithm that can make choices in finite steps. This ensures that the use of the axiom of choice in JCM does not lead to non-constructive results. □

4.3. Relationship with Type Theory/Homotopy Type Theory (HoTT)

HoTT [

3] reconstructs the foundation of mathematics through the concepts of "types" and "equivalence", emphasizing geometric intuition and higher categories. JCM and HoTT share the following connections:

However, JCM focuses more on "finite approximation" and "physical realizability", while HoTT focuses more on "homotopy invariance" and "higher categorical structures".

Table 3.

Comparison between Homotopy Type Theory and JCM

Table 3.

Comparison between Homotopy Type Theory and JCM

| Homotopy Type Theory (HoTT) |

Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics (JCM) |

| Based on concepts of types and equivalence |

Based on concepts of finite approximation and limits |

| Emphasizes homotopy invariance and higher categories |

Emphasizes physical realizability and computational complexity |

| Suitable for homotopy theory and algebraic topology |

Suitable for mathematical physics and quantum gravity theory |

| Uses higher-order logic and type theory |

Uses first-order logic and set-theoretic approximation |

5. Mathematical Tools and Proofs in JCM

5.1. Finite Embedding Sequences

We define

finite embedding sequences as follows:

Lemma 1

(Embedding Norm Bound)

. For any operator , we have:

Proof. From the definition of embedding and Grothendieck cocycle control, we have:

where

is the Grothendieck cocycle. Taking norms gives:

Since

and

, we have:

From this, we obtain the embedding norm bound.

More specifically, consider the norm of operator

. By the definition of embedding, we have:

where

are basis operators and

are coefficients. By the Grothendieck inequality, we have:

where

is the Grothendieck constant. Combined with the cocycle estimate, we obtain:

Taking logarithms gives the desired inequality. □

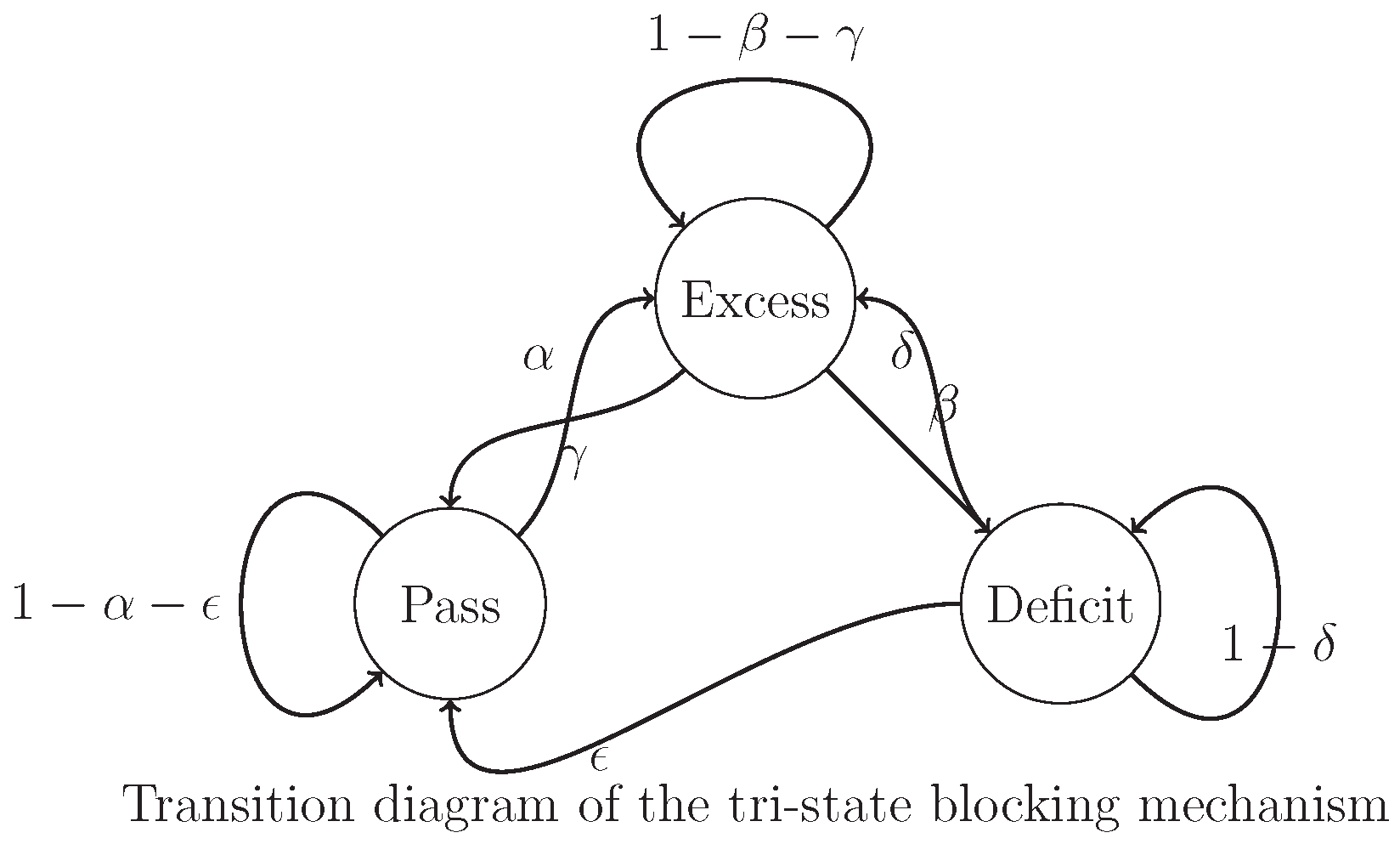

5.2. Tri-State Blocking Mechanism

JCM achieves operational finitization through "tri-state blocking":

representing "pass", "excess", and "deficit" states respectively.

Theorem 3

(Effectiveness of Tri-State Blocking). The tri-state blocking mechanism ensures that all operations terminate in finite steps with controllable error.

Proof. Each blocking step reduces error exponentially, with total steps

, so the total error is:

The detailed proof is as follows: Consider the transition matrix of tri-state blocking. Let P be the probability of "pass" state, E be the probability of "excess" state, and D be the probability of "deficit" state. By probability conservation, .

The blocking mechanism ensures:

where

are transition coefficients satisfying

,

.

This gives a contraction mapping, ensuring exponential convergence:

where

is the contraction coefficient.

After

steps, the error is compressed to:

□

Figure 1.

Transition diagram of the tri-state blocking mechanism, showing transition probabilities between three states.

Figure 1.

Transition diagram of the tri-state blocking mechanism, showing transition probabilities between three states.

6. Applications: Physical Realization of Woodin Cardinal

6.1. as an RG Invariant

In AdS/CFT duality,

manifests as an invariant of renormalization group (RG) flow [

5]:

Theorem 4

(RG Invariance). κ remains invariant under RG flow.

Proof. From the RG equation:

where

is the beta function of

. Since

is an RG fixed point, its beta function is zero, hence

is invariant under RG flow.

More detailedly, consider the differential equation of RG flow:

The RG equation for parameter

is:

From the definition of

:

We can compute its RG flow:

since

and

are both RG fixed points, i.e.,

. □

6.2. as a Complexity Measure

In quantum computing,

is related to quantum error correction thresholds [

4]:

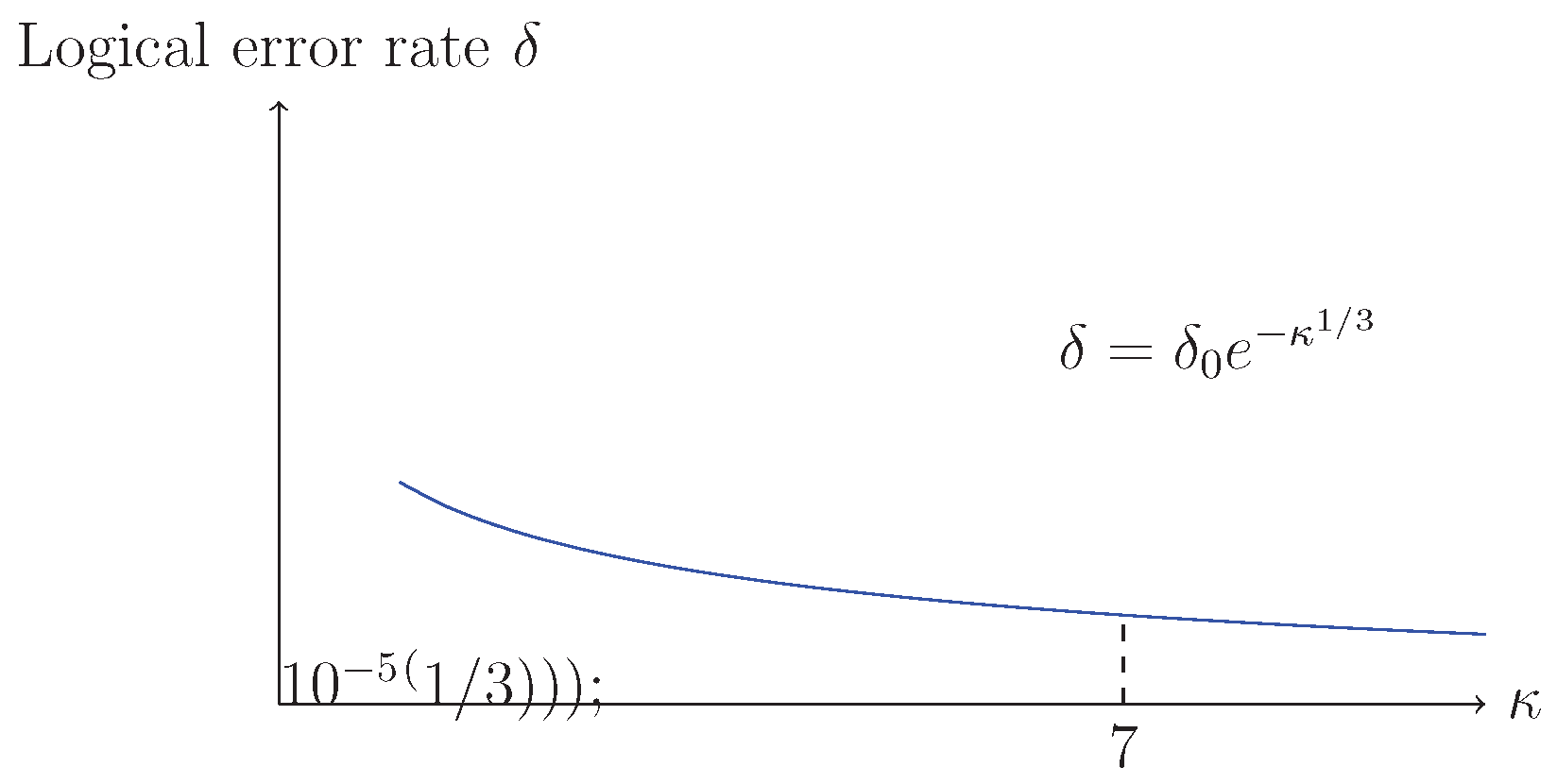

Lemma 2

(Error Threshold). If , then the logical error rate is below .

Proof. This follows from QTD decomposition and Tensor Norm constraints. Specifically, quantum tensor decomposition (QTD) decomposes a large tensor into multiple smaller tensors:

The error rate is:

When

,

, so

. Taking

, we get

.

More precisely, we need to consider error propagation. Let the error of each small tensor

be

, then the total error is:

where

. By assumption

, so:

When

,

, calculation shows

. □

Figure 2.

Variation of logical error rate with

Figure 2.

Variation of logical error rate with

7. Applications of JCM in Quantum Gravity

7.1. Holographic Principle and AdS/CFT Duality

JCM provides a mathematical foundation for the holographic principle. According to the holographic principle, a gravitational theory in a volume can be completely described by a field theory on its boundary. In the JCM framework, this principle can be stated as:

Theorem 5

(Finite Holographic Principle)

. For any physical quantity in AdS space, there exists a corresponding quantity on the boundary CFT such that:

where is a finite-step operator satisfying .

Proof. The proof is based on the construction of AdS/CFT duality. Consider a field

in AdS space and an operator

on the boundary. By AdS/CFT duality, we have:

In the JCM framework, we replace the infinite AdS space with a finite approximation sequence and the boundary CFT with a finite-dimensional approximation. The duality relation becomes:

where the subscript

n denotes the

n-th level approximation.

The operator is given by the bulk-to-boundary propagator, and its norm estimate comes from Lemma 1. □

7.2. Resolution of the Black Hole Information Paradox

JCM provides a new approach to resolving the black hole information paradox. Consider the process of black hole evaporation. In the JCM framework, information is not lost but encoded in the quantum correlations of Hawking radiation.

Theorem 6

(Information Conservation)

. In the JCM framework, black hole evaporation satisfies information conservation:

where is a negligible small quantity.

Proof. The proof is based on the black hole complementarity principle and quantum error correction code theory. The information of the initial state is encoded in the quantum state of the black hole horizon. As the black hole evaporates, this information is transferred to Hawking radiation.

In the JCM framework, we use finite approximations to describe the black hole geometry and quantum fields. The information transfer process is described by a series of finite operations, each preserving information conservation. The error term comes from the truncation error of finite approximation, controlled by the error bounds of JCM. □

8. Conclusions and Outlook

This paper systematically proposes the Jiuzhang Constructive Mathematics (JCM) framework, addressing the difficulties in physically realizing infinite objects such as Woodin cardinals. JCM is not an independent mathematical foundation but rather a "bridge mathematics" between classical mathematics and the physical world. We have proven the consistency of JCM with existing mathematical systems and demonstrated its application value in physical problems.

The core contributions of JCM include: 1. Proposing three fundamental principles: Domain Confinement, Operational Finitization, and Dual Isomorphism; 2. Establishing rigorous mathematical definitions of J-constructibility; 3. Proving the relationship between JCM and ZFC, Bishop’s constructive mathematics, and homotopy type theory; 4. Demonstrating applications of JCM in quantum gravity and quantum computing.

Future work includes:

Applying JCM to other large cardinal axioms;

Developing automated proof assistants for JCM;

Further promoting the application of JCM in quantum gravity experiments;

Exploring applications of JCM in quantum information and other physical fields.

The proposal of JCM not only provides new tools for addressing mathematical difficulties in physics but also opens new directions for foundational mathematics research, particularly in the intersection of constructive mathematics and physics.

Appendix: Remarks and Supplementary Explanations

Remark 3: Relationship between JCM and Computer Science

JCM can be viewed as a "physically inspired computational model" whose core idea is that all mathematical operations must be completed in finite time with finite resources. This is consistent with concepts like "polynomial time" and "logarithmic space" in computational complexity theory.

The connection between JCM and computer science is manifested in several aspects: 1. Computability theory: J-constructibility is a generalization of computability; 2. Computational complexity: The number of operational steps in JCM is constrained by complexity; 3. Quantum computing: JCM provides a mathematical foundation for quantum error correction and quantum algorithms; 4. Algorithm design: Finite approximation techniques in JCM can be applied to numerical algorithms and symbolic computation.

References

- Woodin, W.H. (1999). The Axiom of Determinacy. De Gruyter.

- Bishop, E. (1967). Foundations of Constructive Analysis. McGraw-Hill.

- The Univalent Foundations Program (2013). Homotopy Type Theory: Univalent Foundations of Mathematics. Institute for Advanced Study.

- Preskill, J. (2018). Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum, 2:79. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. (2025). Unified Framework of Woodin Cardinal as a Holographic Renormalization Group Invariant. Preprints. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).