Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work on Differential Equations and Fractional Calculus

3. Preliminaries on Fractional Calculus

4. Fractional Model for In-System Mechanics

4.1. Classical Coordinate Transformations

4.2. Fractional Extension of Length Contraction

4.3. Fractional Time Dilation

5. Discussion

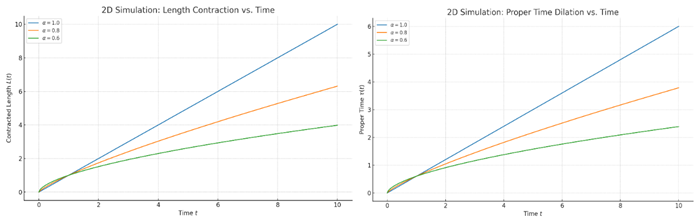

2D Simulations

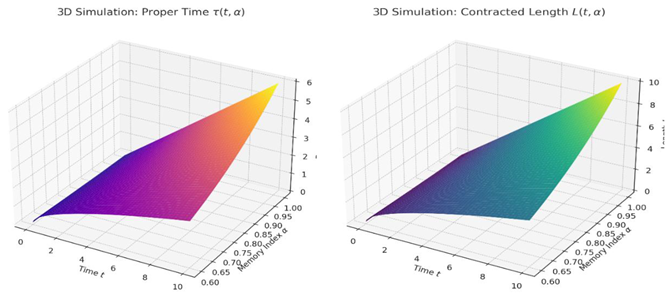

3D Simulations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- A. Einstein, “On the electrodynamics of moving bodies,” 1905.

- Xie, W., Huang, G., Fu, W., Du, S., Cui, B., Li, M., & Tan, Y. (2023). Rapid estimation of undifferenced multi-GNSS real-time satellite clock offset using partial observations. Remote Sensing, 15(7), 1776. [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. (2010). An introduction to mathematical models. Fractional calculus and waves in linear viscoelasticity. Imperial College Press, London.

- Bagley, R. L., & Torvik, P. J. (1983). A theoretical basis for the application of fractional calculus to viscoelasticity. Journal of rheology, 27(3), 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Riewe, F. (1997). Mechanics with fractional derivatives. Physical Review E, 55(3), 3581.

- Nasrolahpour, H. (2011). Fractional Modified Special Relativity. arXiv preprint arXiv:1104.0030.

- Demir, T., & Hajrulla, S. (2023). Discrete Fractional Operators and their applications. International Journal of Advanced Natural Sciences and Engineering Researches (IJANSER).

- Hajrulla, S., Uka, A., & Demir, T. (2023). Simulations and results for the heat transfer problem. European Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 6(1), 1-9.

- Demir, T., Hajrulla, S., Ozer, O., Karadeniz, S., & James, O. O. C. (2024). Caputo Fractional Operator on shallow water wave theory. International Journal of Advanced Natural Sciences and Engineering Researches, 8(7), 1-41.

- Demir, T., & Samei, M. E. Applications of q-Mittag Leffler function on q-fractional differential operators. In 6th International HYBRID Conference on Mathematical Advances and Applications (p. 191).

- DEMİR, T. (2022). Mittag-Leffler Function and Integration of the Mittag-Leffler Function.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). Existence and Uniqueness Analysis in q-Calculus-Based Dynamic Systems.

- Demir, T. (2024, December). Asymptotic Analysis of Fractional Derivatives and Applications.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). Numerical and theoretical Analysis of Existence and Uniqueness Analysis in q-Calculus-Based Dynamic Systems.

- Demir, T. (2025). A Novel Fractional Differential Model with ψ-Caputo Operator: Theory, Analysis, and Numerical Simulations.

- Demir, T. (2024, December). Delay Differential Equation Approach to Lotka-Volterra Predator-Prey Dynamics: Modelling Ecological Interactions with Time Delays.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). The Application of the Wronskian Determinant in Algebraic Structures and Its Role in Mathematical Analysis.

- Demir, T., Hajrulla, S., & Doğan, P. Using Special Functions on Grünwald-Letnikov and Riemann Liouville Fractional Derivative and Fractional Integral.

- Demir, T. (2022). Solutions of fractional-order differential equation on harmonic waves and linear wave equation. Solutions of fractional-order differential equation on harmonic waves and linear wave equation.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). Simulations of Fractional Variational Calculus and Its Interplay with Wronskian Determinants in Solving Advanced Differential Equations.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). Fractional Variational Calculus and Its Interplay with Wronskian Determinants in Solving Advanced Differential Equations.

- Demir, T. (2025). Hybrid Fractional-Order Models with Data-Driven Parameters for Complex Systems: Theory, Deep Learning Integration, and Multiscale Applications.

- Demir, T. Laplace Transforms of the Fractional Derivatives.

- Demir, T. (2025, January). The Application of the Wronskian Determinant in Algebraic Structures and Its Role in Mathematical Analysis.

- Demir, T., & Hajrulla, S. (2025). Eco-Epidemiological Dynamics Under State-Dependent Delays: A New Delay Differential Approach. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Demir, T., (2025, January). Fractional-order derivatives on generalized functions and their applications.

- Hajrulla, S., & Demir, T. Discrete Fractional Operators in Analyzing Digital Financial Inclusion in Banks by using Linear Fractional Differential Equation Model. In 7th International Conference On Mathematical Modelling, Applied Analysis And Computation (ICMMAAC-24).

- Demir, T. (2025). Generalized Fractional Symmetry Principles and Conservation Laws in Nonlinear Multiscale Systems: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications.

- Demir, T. (2023). Fractional Models on Surface Waves. Academie. edu.

- Hajrulla, S., & Demir, T. Numerical Results for Second-Level Banks Data Using Discrete Fractional Calculus. In 7th International Conference On Mathematical Modelling, Applied Analysis And Computation (ICMMAAC-24).

- Demir, T. (2025). Fractional-Order Modeling, Control, and Fault Diagnosis in Intelligent Mechatronic Systems: Theory, Algorithms, and Real-Time Applications.

- Demir, T. Application of fractional-order Differential Equations on Diffusion and Wave Equations.

- Demir, T. Fractional Noether-Type Theorems via ψ-Caputo Derivatives for Systems with Non-Conservative Forces.

- Demir, T. Data-Driven Fractional Modeling and Predictive Digital Twins for Cyber-Physical Mechatronic Systems: Theory, Machine Learning, and Experimental Validation.

- Demir, T. Unified Theory and Intelligent Simulation Platform for Coupled Multi-Physics, Multi-Scale, and Fractional-Order Systems: Foundations, Algorithms, and Digital Twin Applications.

- Demir, T., Cherif, M. H., Hajrulla, S., & Erikçi, G. Local Fractional Differential Operators on Heat Transfer Modelling.

- Demir, T. Fractional Stochastic Differential Equations and Deep Learning for Systemic Risk Forecasting in Complex Financial Networks.

- Demir, T. Spectral Theory and Well-Posedness for Nonlocal and Variable-Order Fractional Differential Operators on Irregular Domains.

- Demir, T. Fractional-Order Modeling and AI-Driven Forecasting of Soil Moisture Dynamics for Sustainable Agriculture and Climate Resilience.

- Demir, T. Fractional-Order Networked Control for Large-Scale Cyber-Physical Systems under Adversarial Attacks: Theory, Secure Algorithms, and Smart Grid Applications.

- Demir, T. Data-Driven Fractional Partial Differential Equations for Anomalous Transport and Pattern Formation in Living Systems: Theory, Machine Learning Algorithms, and Bioengineering Applications.

- Demir, T., Baleanu, D., Heydari, M. H., Jajarmi, A., & Akgül, A. Caputo fractional operator with Proportional-Integral-Derivative controller.

- Kilbas, A. A. (2006). Theory and applications of fractional differential equations. North-Holland Mathematics Studies, 204.

- Podlubny, I. (1998). Fractional differential equations: an introduction to fractional derivatives, fractional differential equations, to methods of their solution and some of their applications (Vol. 198). elsevier.

- Mainardi, F. (2010). An introduction to mathematical models. Fractional calculus and waves in linear viscoelasticity. Imperial College Press, London.

- Tarasov, V. E. (2011). Fractional dynamics: applications of fractional calculus to dynamics of particles, fields and media. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Laskin, N. (2000). Fractional quantum mechanics. Physical Review E, 62(3), 3135. [CrossRef]

- Machado, J. T. (2015). Fractional order junctions. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 20(1), 1-8.

- Garrappa, R., & Kaslik, E. (2020). On initial conditions for fractional delay differential equations. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 90, 105359. [CrossRef]

- Ortigueira, M. D. (2011). Fractional calculus for scientists and engineers (Vol. 84). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Bagley, R. L., & Torvik, P. J. (1983). A theoretical basis for the application of fractional calculus to viscoelasticity. Journal of rheology, 27(3), 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Nottale, L. (2011). Scale relativity and fractal space-time: a new approach to unifying relativity and quantum mechanics. World Scientific.

- Einstein, A. (1905). On the electrodynamics of moving bodies.

- Sikoka, Johannes (2025). An approximation for the advent of In-system mechanics in the theory of relativity. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).