Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

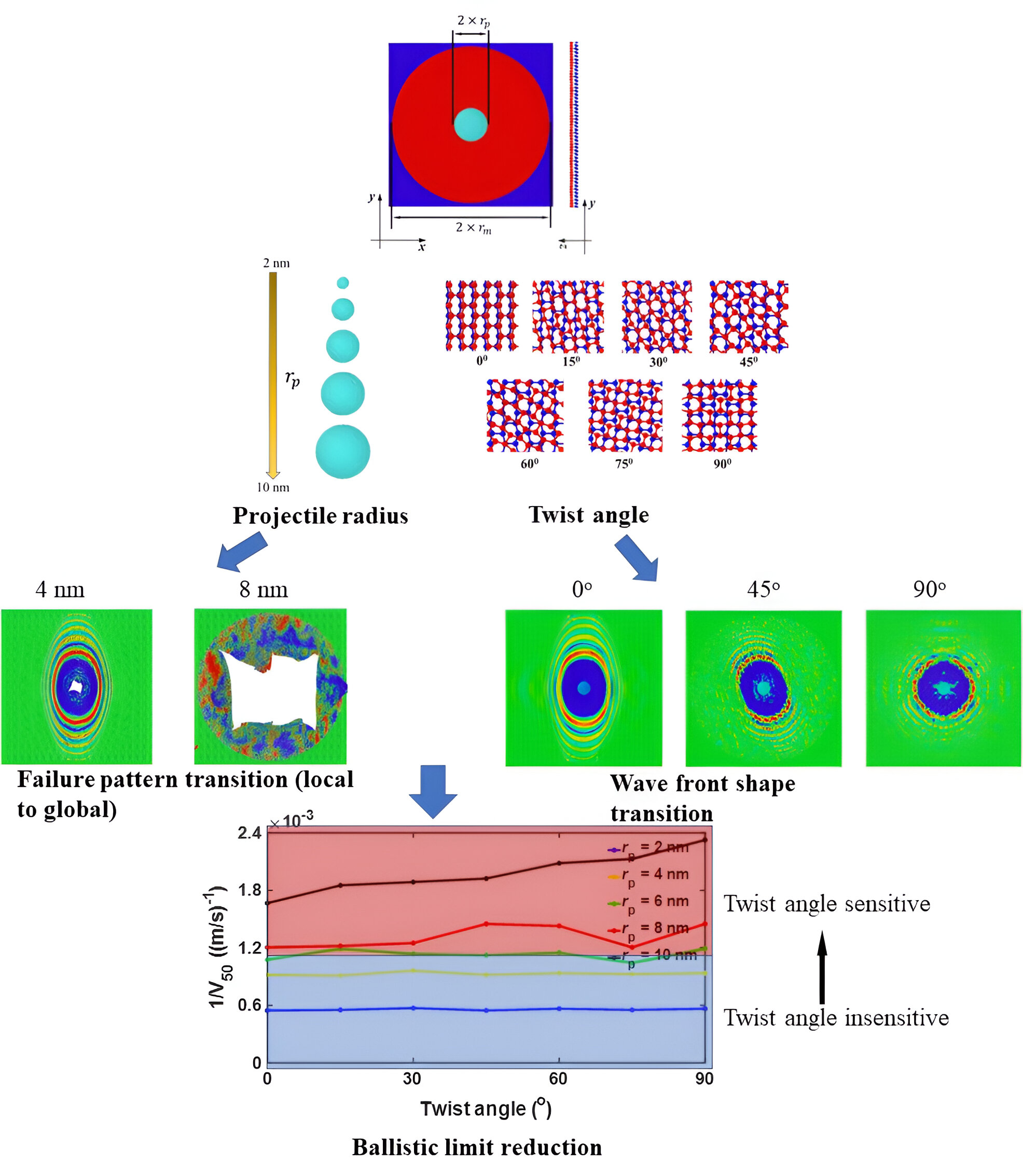

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

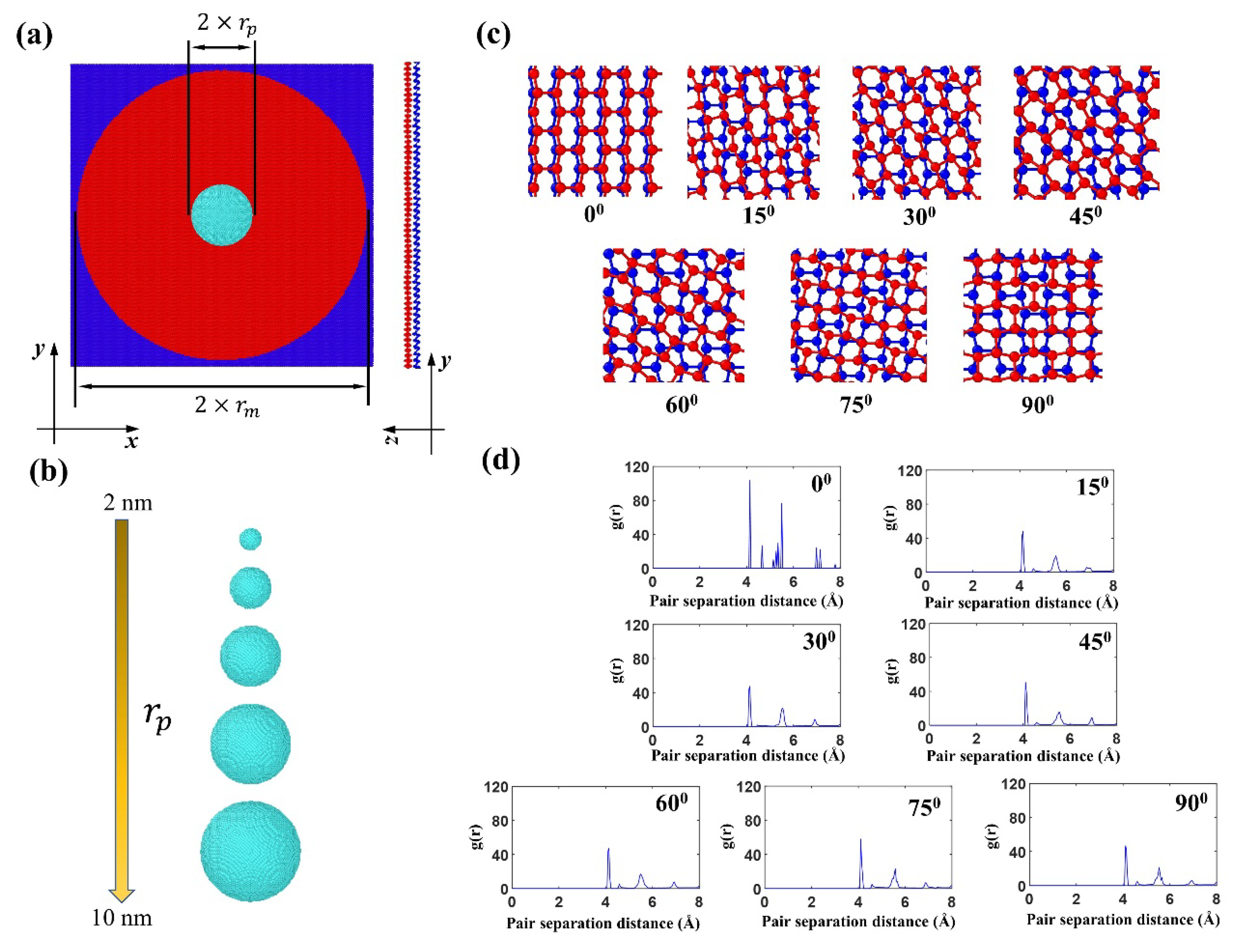

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

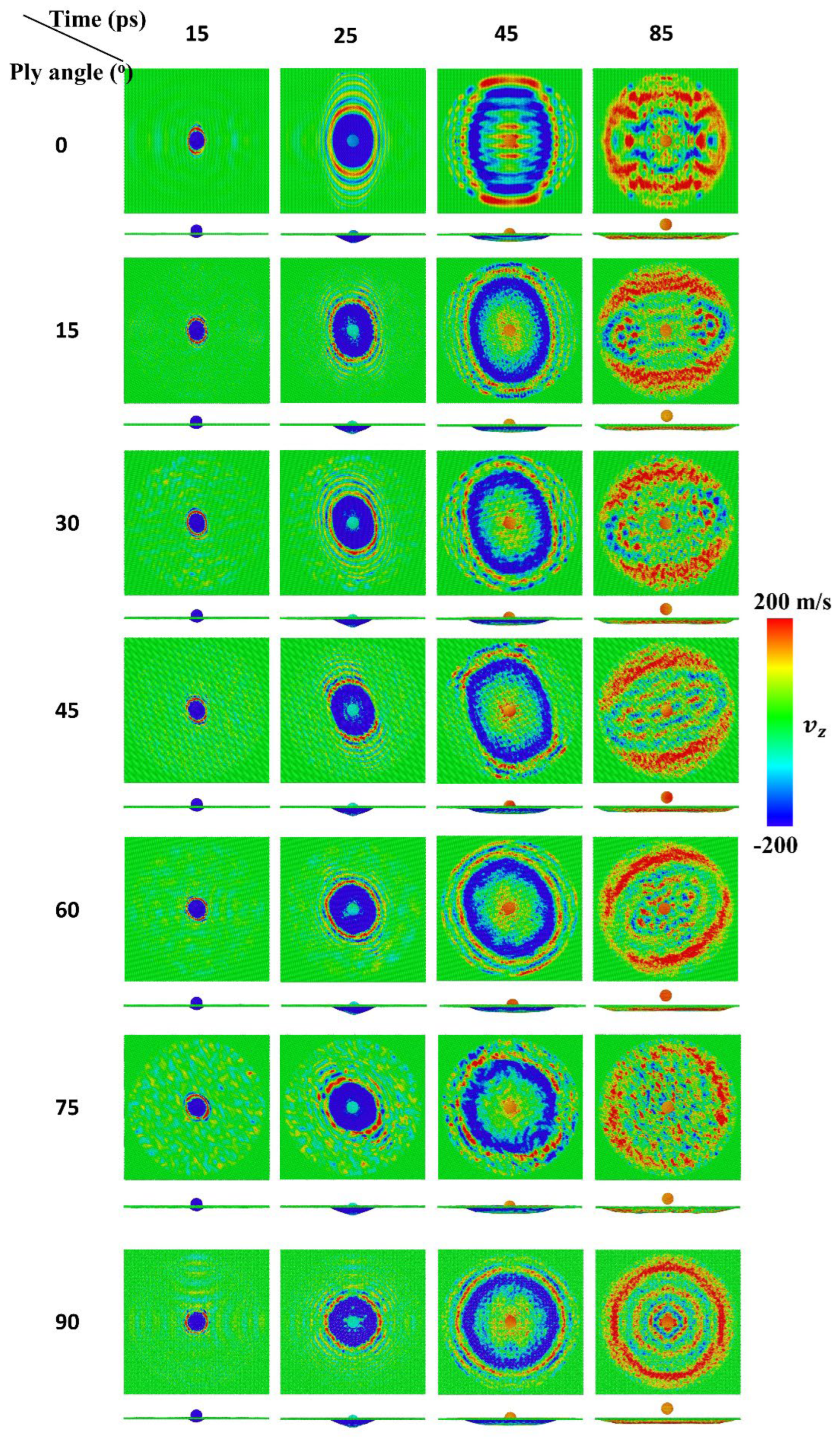

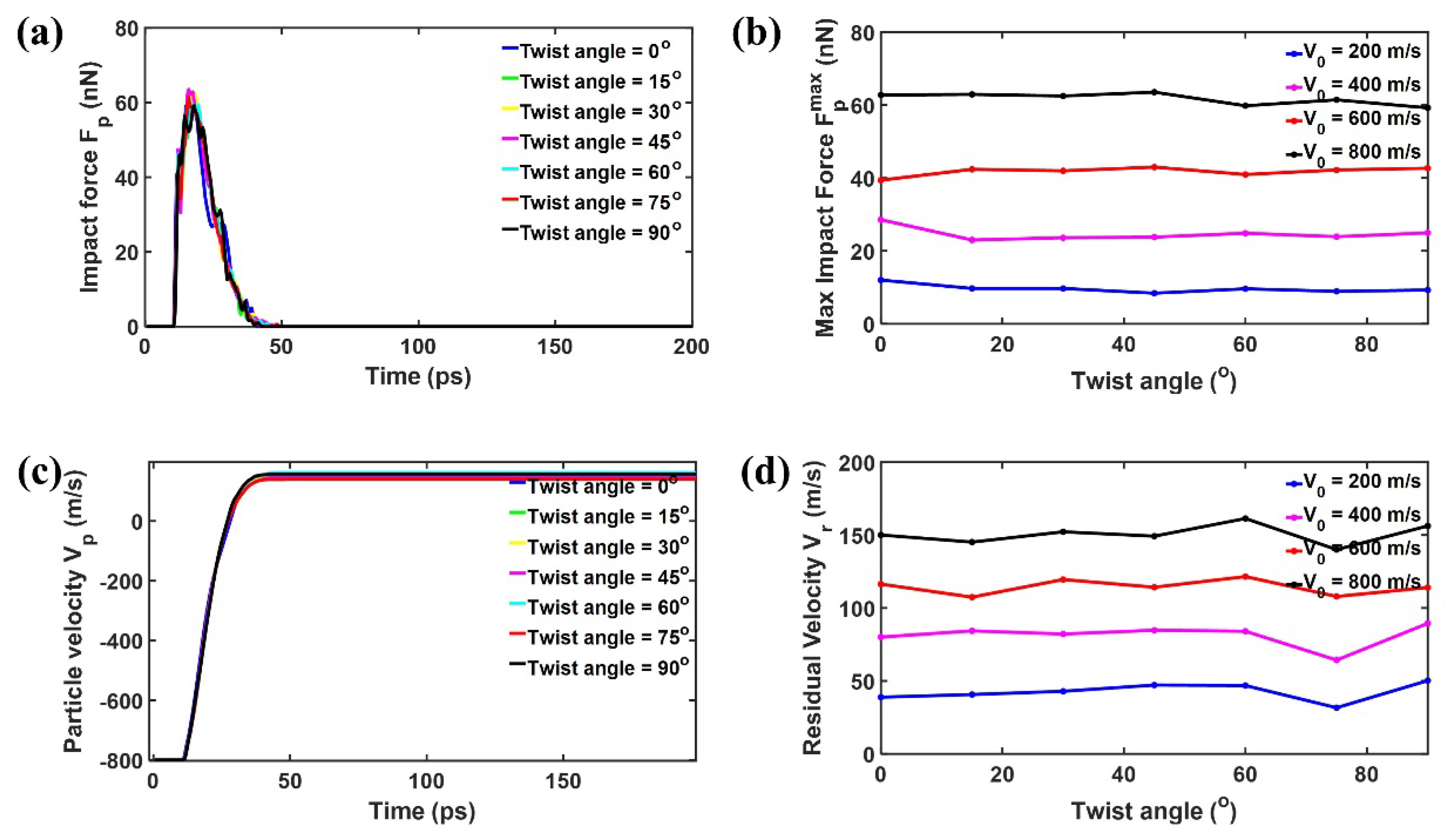

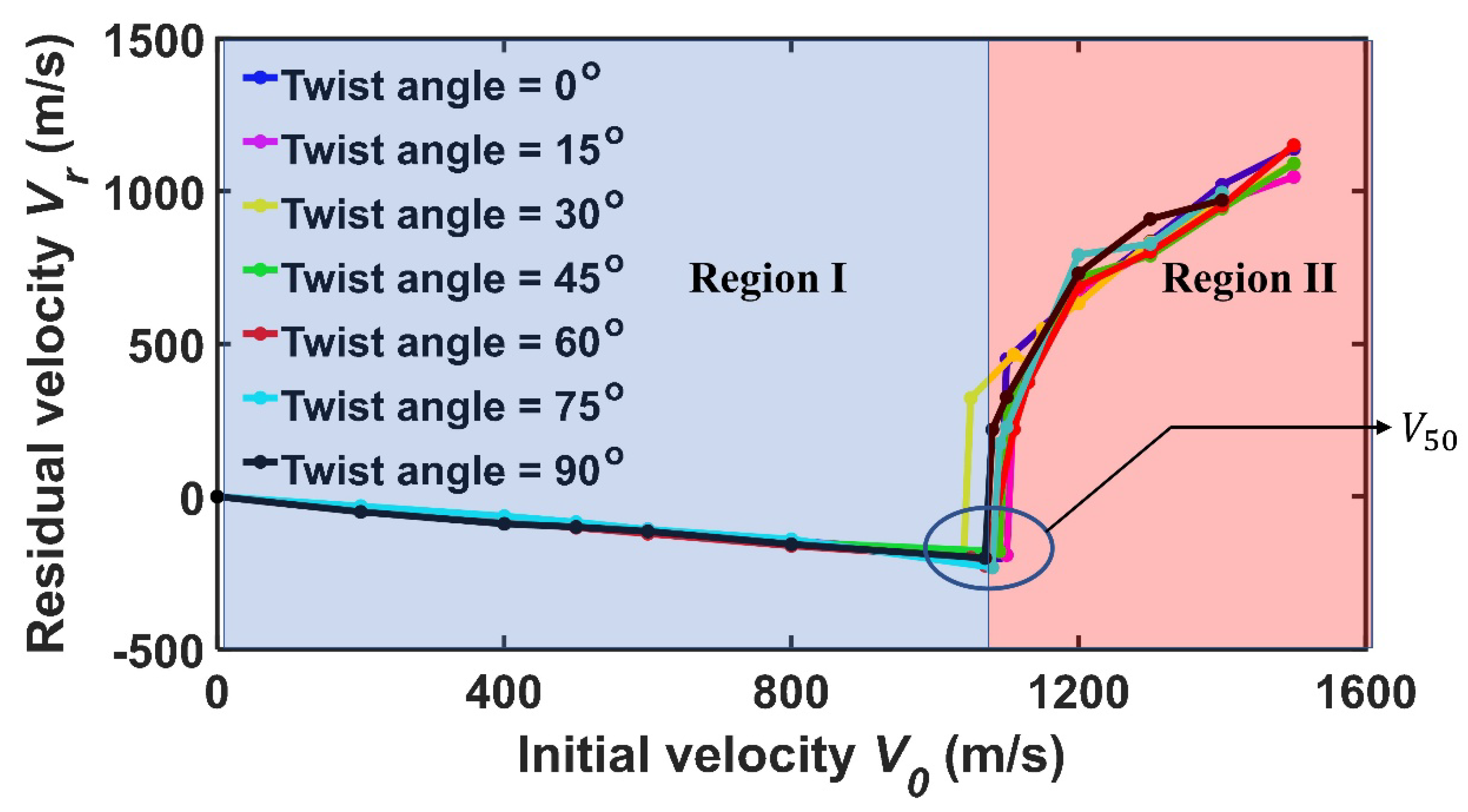

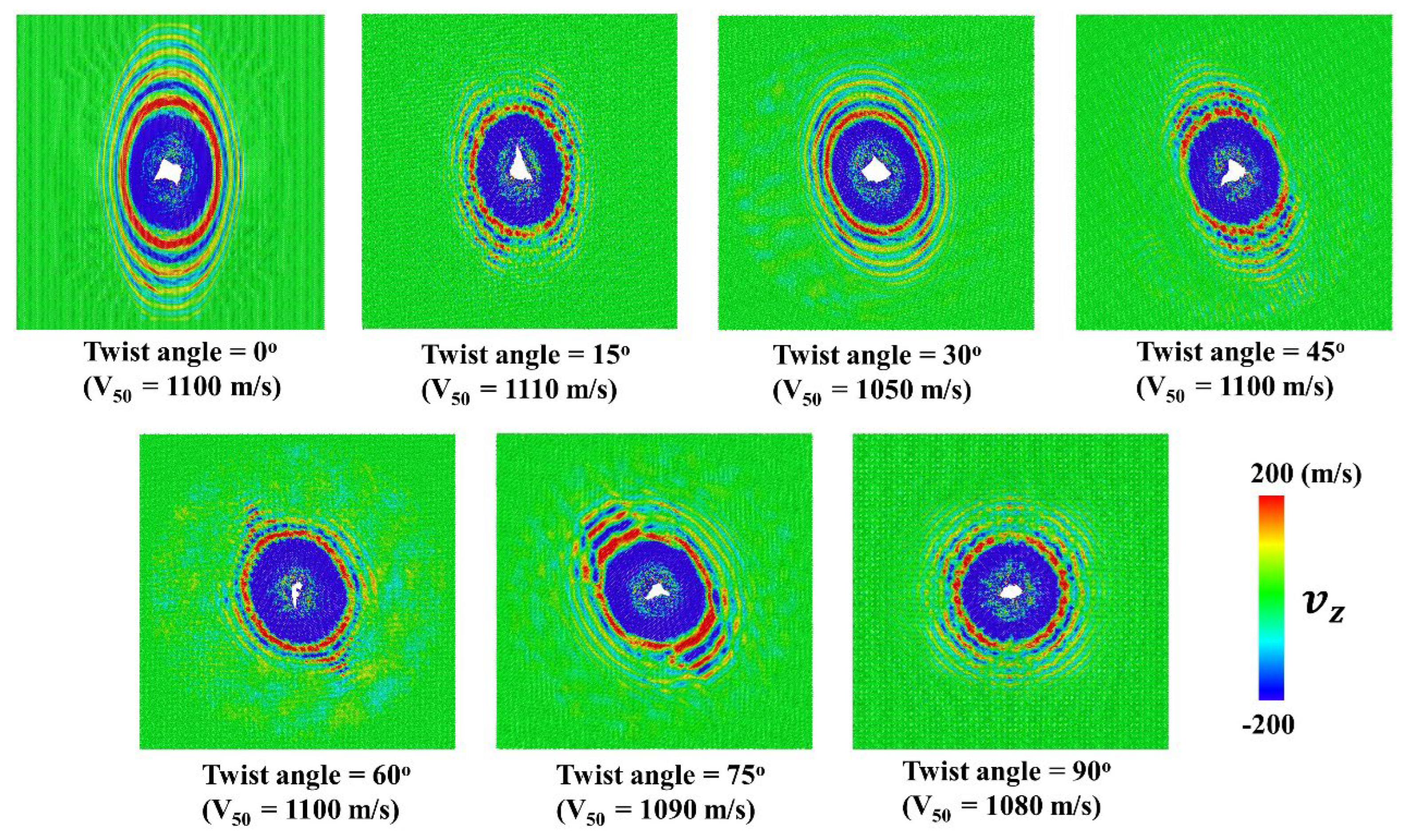

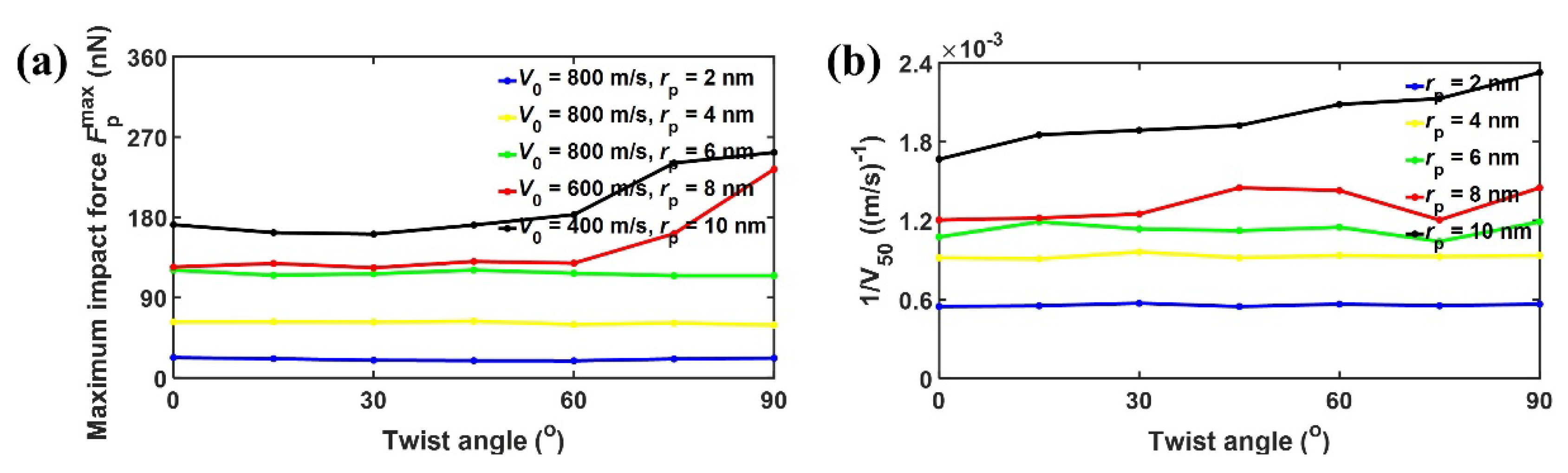

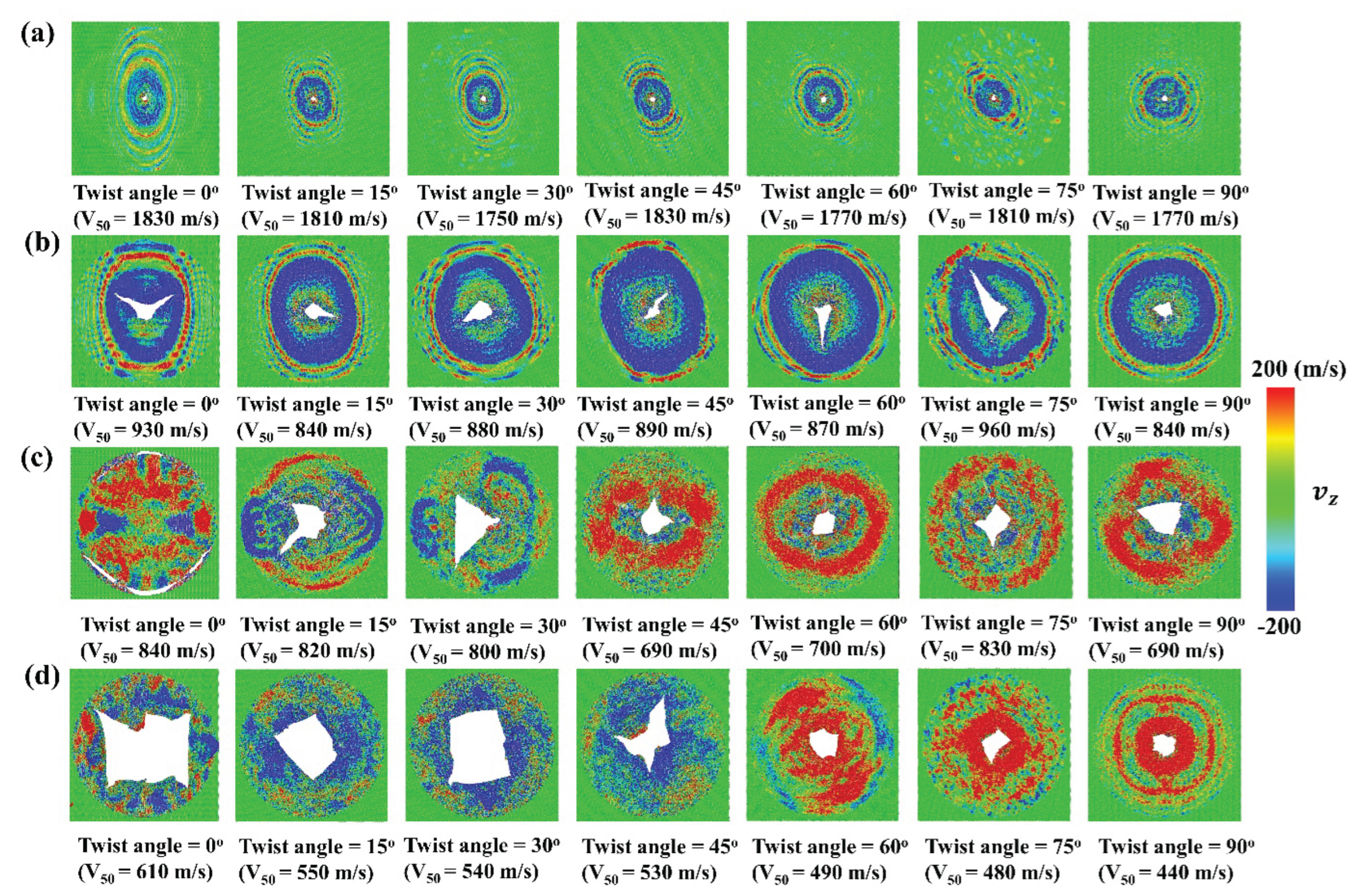

3.1. Effect of Twist Angle on the Impact Performance

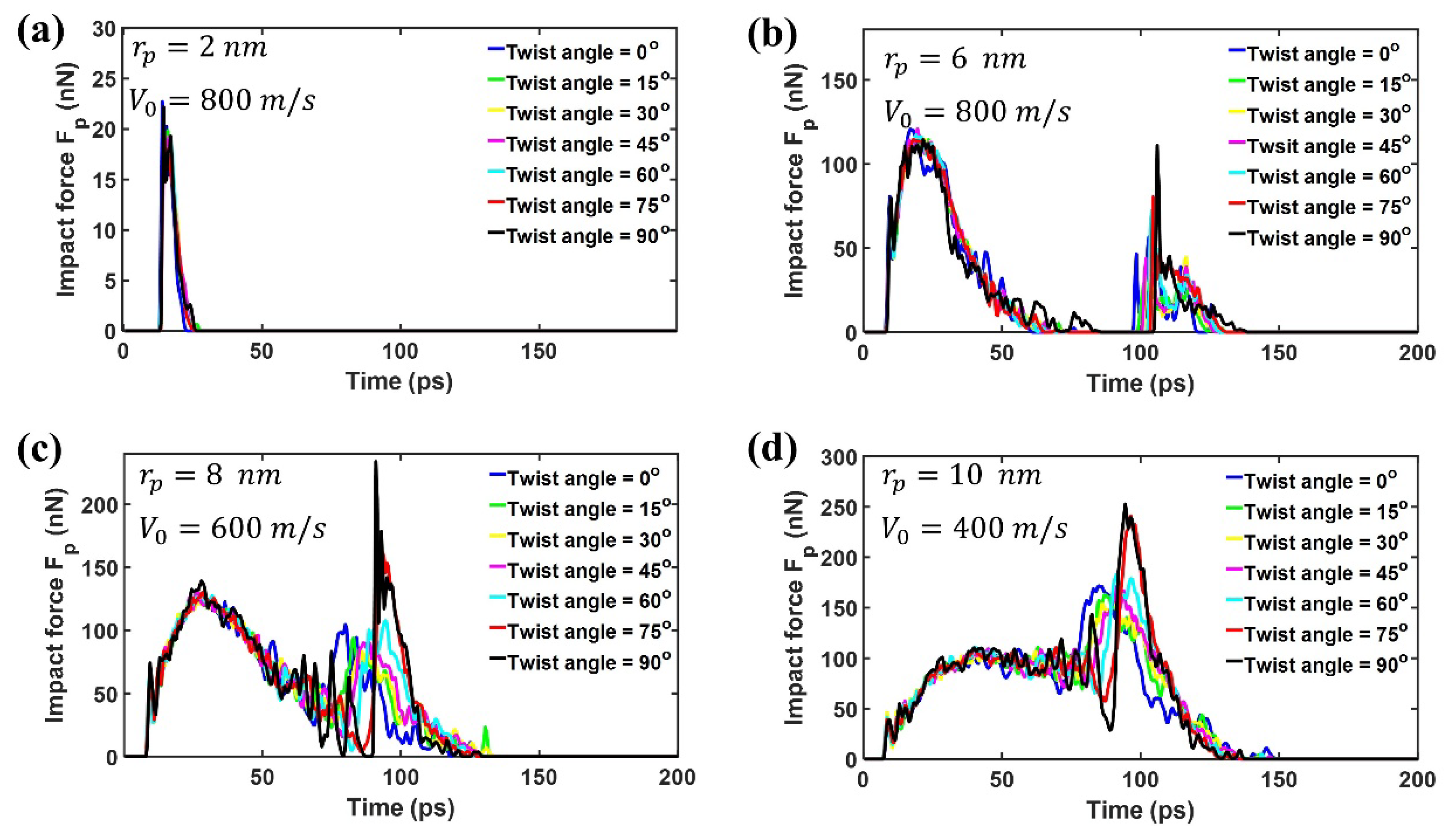

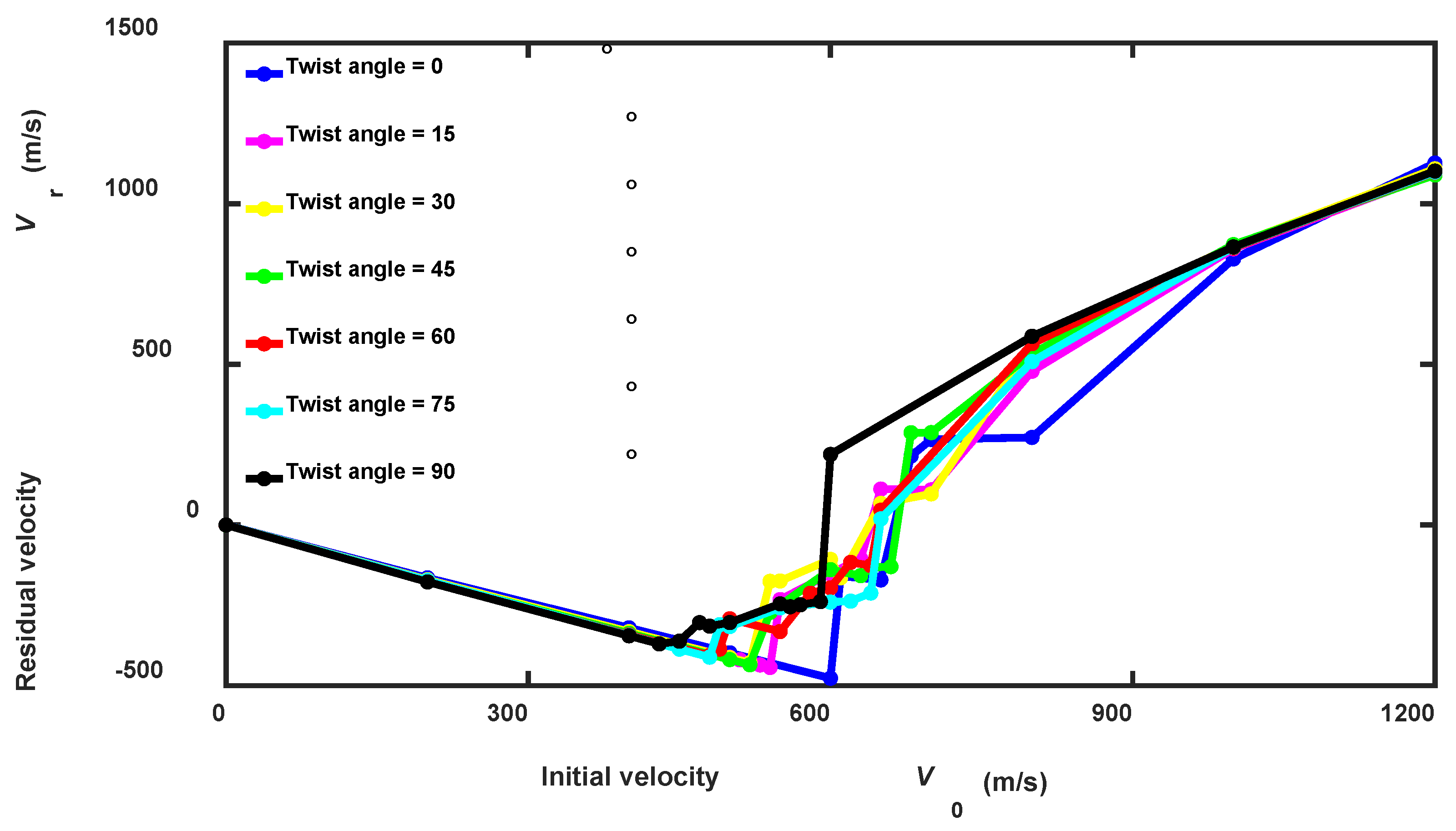

3.2. Effect of Projectile Radius on the Impact Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| CG | Coarse-grained |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

References

- Bidhendi, M.R.T.; Behdinan, K. Graphene oxide coated silicon carbide films under projectile impacts. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chiang, C.-C.; Meng, Z. Investigation of dynamic impact responses of layered polymer-graphene nanocomposite films using coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Carbon 2022, 203, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xue, S.; Jiang, J. Molecular dynamics study on the thermal conductivity and ballistic resistance of twisted graphene. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Guo, J.-G. Theoretical investigation on energy absorption of single-layer graphene under ballistic impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepelev, I.; Dmitriev, S.; Korznikova, E. Molecular dynamics simulation of high-speed loading of 2D boron nitride. Lett. Mater. 2021, 11, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Lee, J.-H. Intrinsic Dynamics and Toughening Mechanism of Multilayer Graphene upon Microbullet Impact. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 9185–9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Becton, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Zeng, X.; Pidaparti, R.; Wang, X. A coarse-grained model for mechanical behavior of phosphorene sheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Han, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Balogun, O.; Keten, S. Spalling-like failure by cylindrical projectiles deteriorates the ballistic performance of multi-layer graphene plates. Carbon 2018, 126, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, B. Twisted bilayer graphene/h-BN under impact of a nano-projectile. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Suksangpanya, N.A. Yaraghi, D. Kisailus, P. Zavattieri, Twisting cracks in Bouligand structures, Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 76 (2017) 38-57.

- Meng, Q.; Gao, Y.; Shi, X.; Feng, X.-Q. Three-dimensional crack bridging model of biological materials with twisted Bouligand structures. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Liu, R. Pidaparti, X. Wang, Abnormal linear elasticity in polycrystalline phosphorene, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 20(13) (2018) 8668-8675.

- Yang, Z.; Ma, F.; Xu, K. Grain boundaries guided vibration wave propagation in polycrystalline graphene. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24667–24673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Hong, J.; Zeng, X.; Pidaparti, R.; Wang, X. Fracture mechanisms in multilayer phosphorene assemblies: from brittle to ductile. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 13083–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Hong, J.; Pidaparti, R.; Wang, X. Abnormality in fracture strength of polycrystalline silicene. 2D Mater. 2016, 3, 035008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Hong, J.; Pidaparti, R.; Wang, X. Fracture patterns and the energy release rate of phosphorene. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 5728–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazyev, O.V.; Chen, Y.P. Polycrystalline graphene and other two-dimensional materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Artyukhov, V.I.; Yakobson, B.I.; Xu, Z. Pseudo Hall–Petch Strength Reduction in Polycrystalline Graphene. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 1829–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Liaghat, G.; Charandabi, S.C. High velocity impact on composite sandwich panels with nano-reinforced syntactic foam core. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dong, J.; Xiao, K.; Jiang, M.; Huang, C.; Wu, X. Impact behavior of advanced films under micro- and nano-scales: A review. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.M.; Chen, S.H.; Souna, A.J.; Stranick, S.J.; Soles, C.L.; Chan, E.P. The Projectile Perforation Resistance of Materials: Scaling the Impact Resistance of Thin Films to Macroscale Materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 32916–32925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Yin, Q.; Wu, X.; Huang, C. Mechanical behavior of single-layer graphdiyne via supersonic micro-projectile impact. Nano Mater. Sci. 2022, 4, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A.L.; Chan, E.P.; Lawrimore, W.B.; Newman, J.K. Supersonic Impact Response of Polymer Thin Films via Large-Scale Atomistic Simulations. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 5991–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Giuntoli, A.; Hansoge, N.; Lin, Z.; Keten, S. Scaling for the inverse thickness dependence of specific penetration energy in polymer thin film impact tests. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.L.; Giuntoli, A.; Fermen-Coker, M.; Keten, S. Tailoring flake size and chemistry to improve impact resistance of graphene oxide thin films. Carbon 2023, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, B.; Singh, S.P.; Mahajan, P. Influence of temperature and size of the projectile on perforation of graphene sheet under transverse impact using molecular dynamics. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Niu, F.; Ademiloye, A. Molecular dynamics simulation of perforation of graphene under impact by fullerene projectiles. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, X. Stress wave response in a two-dimensional membrane subjected to hypervelocity impact of a micro-flyer. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhu, X.; Ren, Y.; Chen, W. Ballistic performance of additive manufacturing metal lattice structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Huang, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, W. Ballistic impact responses and failure mechanism of composite double-arrow auxetic structure. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, H.; Li, X.; Hu, Q.; Yan, K.; Qi, S.; Yuan, M. Experimental and numerical study on ballistic response of stitched aramid woven fabrics under normal and oblique dynamic impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, K.P.; Tran, T.T.; Lee, T.; Choi, W.; Peterson, S.F.; Marmolejo-Tejada, J.M.; Bahng, J.; Lee, D.; Dat, V.K.; Kim, J.; et al. Giant Modulation of Interlayer Coupling in Twisted Bilayer ReS2. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2500411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; An, M.; Song, D.; Fan, A.; Chen, D.; Wang, H.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X. Phonon magic angle in two-dimensional puckered homostructures. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 12741–12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.H.; Goh, Y.M.; Yoo, H.; Engelke, R.; Xie, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Ye, A.; Deotare, P.B.; Tadmor, E.B.; et al. Torsional periodic lattice distortions and diffraction of twisted 2D materials. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøggild, P.; Booth, T.J. The delicate art of twisting 2D materials. Newton 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.F.; Liu, B.; Guo, Z.-X. Giant twist-angle dependence of thermal conductivity in bilayer graphene originating from strong interlayer coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, L241405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapfer, M.; Jessen, B.S.; Eisele, M.E.; Fu, M.; Danielsen, D.R.; Darlington, T.P.; Moore, S.L.; Finney, N.R.; Marchese, A.; Hsieh, V.; et al. Programming twist angle and strain profiles in 2D materials. Science 2023, 381, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.; Wang, X.; Grove-Rasmussen, K.; Wei, Z. Twist-angle two-dimensional superlattices and their application in (opto)electronics. J. Semicond. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviness, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Z. Improved Ballistic Impact Resistance of Nanofibrillar Cellulose Films With Discontinuous Fibrous Bouligand Architecture. J. Appl. Mech. 2023, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Marchi, B.C.; Meng, Z.; Keten, S. Impact resistance of nanocellulose films with bioinspired Bouligand microstructures. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Loya, P.E.; Lou, J.; Thomas, E.L. Dynamic mechanical behavior of multilayer graphene via supersonic projectile penetration. Science 2014, 346, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Singh, A.; Qin, X.; Keten, S. Reduced ballistic limit velocity of graphene membranes due to cone wave reflection. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2017, 15, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Qin, X.; Keten, S. Ballistic impact response of lipid membranes. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 4761–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Keten, S. Analysis of Cone Wave Reflection in Finite-Size Elastic Membranes and Extension of the Ballistic Impact Problem From Elastic to Viscoelastic Membranes. J. Appl. Mech. 2018, 85, 081004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürel, U.; Keten, S.; Giuntoli, A. Bidispersity Improves the Toughness and Impact Resistance of Star-Polymer Thin Films. ACS Macro Lett. 2024, 13, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.L.; Giuntoli, A.; Fermen-Coker, M.; Keten, S. Tailoring flake size and chemistry to improve impact resistance of graphene oxide thin films. Carbon 2023, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Lin, J.; Xiao, R.; Zhou, H. Unravelling physical origin of the Bauschinger effect in glassy polymers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Keten, S. Micro-ballistic response of thin film polymer grafted nanoparticle monolayers. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 7926–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.; Ostadhossein, A.; van Duin, A.C. Atomistic-scale simulations of the chemomechanical behavior of graphene under nanoprojectile impact. Carbon 2016, 99, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, B.Z. (.; Chowdhury, S.C.; Gillespie, J.W. Molecular simulations of stress wave propagation and perforation of graphene sheets under transverse impact. Carbon 2016, 102, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidhendi, M.R.T.; Behdinan, K. High-velocity transverse impact of monolayer graphene oxide by a molecular dynamics study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Guo, J.-G. Theoretical investigation on energy absorption of single-layer graphene under ballistic impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.C.T. van Duin, A. Strachan, S. Stewman, Q.S. Zhang, X. Xu, W.A. Goddard, ReaxFFSiO reactive force field for silicon and silicon oxide systems, Journal of Physical Chemistry A 107(19) (2003) 3803-3811.

- Brenner, D.W.; Shenderova, O.A.; Harrison, J.A.; Stuart, S.J.; Ni, B.; Sinnott, S.B. A second-generation reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential energy expression for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.J.; Tutein, A.B.; Harrison, J.A. A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 6472–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Bessa, M.A.; Xia, W.; Liu, W.K.; Keten, S. Predicting the Macroscopic Fracture Energy of Epoxy Resins from Atomistic Molecular Simulations. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 9474–9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Zhan, H.; Hu, D.; Gu, Y. Failure mechanism of monolayer graphene under hypervelocity impact of spherical projectile. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).