Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Data Source

Study Population

Study Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

Results

Patient Population

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

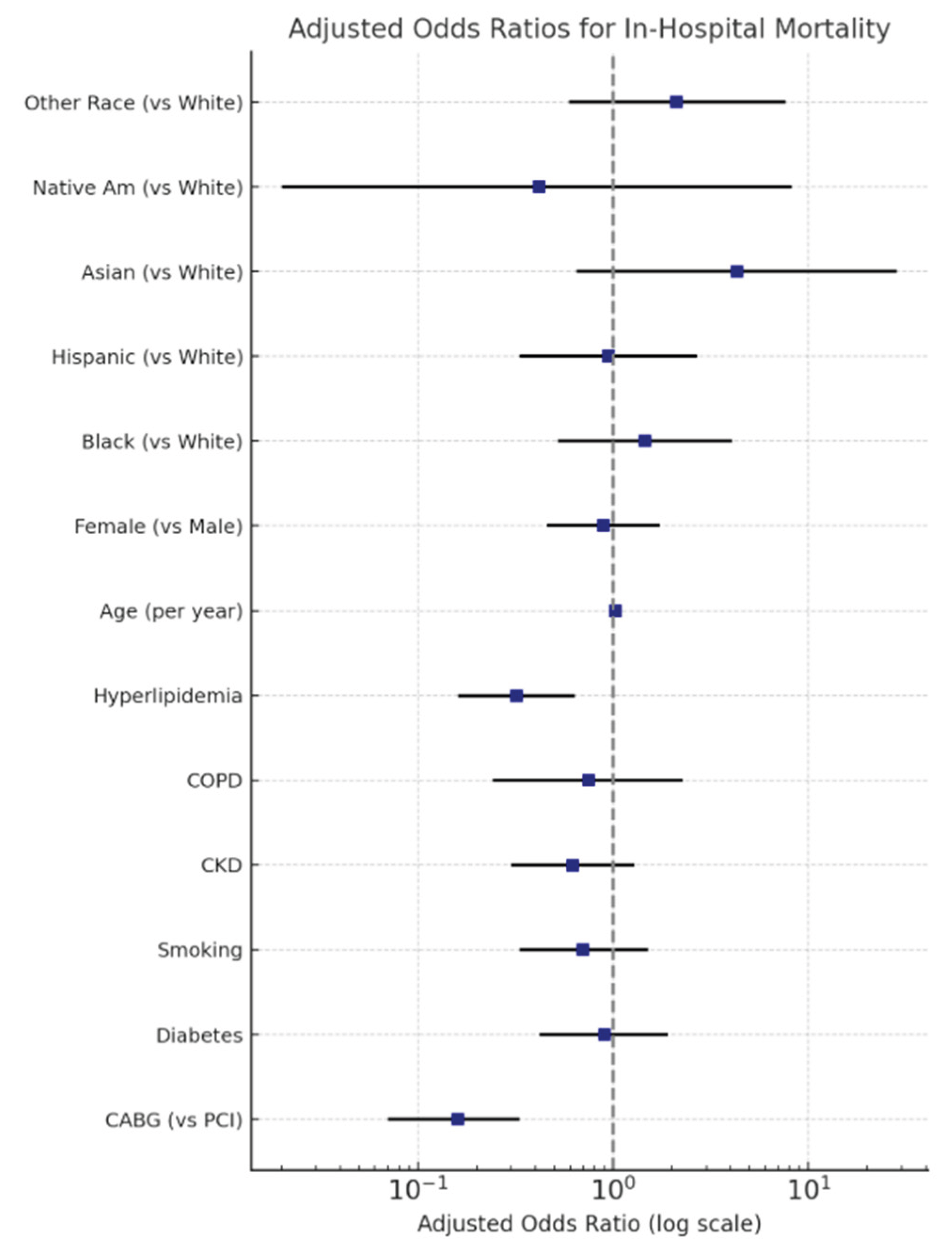

In-Hospital Mortality

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

References

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; Fang, J.C.; Fedson, S.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hayek, S.S.; Hernandez, A.F.; Khazanie, P.; Kittleson, M.M.; Lee, C.S.; Link, M.S.; Milano, C.A.; Nnacheta, L.C.; Sandhu, A.T.; Stevenson, L.W.; Vardeny, O.; Vest, A.R.; Yancy, C.W. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022, 79, e263–e421, Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1551. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsterdam, E.A.; Wenger, N.K.; Brindis, R.G.; Casey DEJr Ganiats, T.G.; Holmes DRJr Jaffe, A.S.; Jneid, H.; Kelly, R.F.; Kontos, M.C.; Levine, G.N.; Liebson, P.R.; Mukherjee, D.; Peterson, E.D.; Sabatine, M.S.; Smalling, R.W.; Zieman, S.J.; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014, 130, e344–426, Erratum in Circulation. 2014, 130, e433-e434. Dosage error in article text. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Gara, P.T.; Kushner, F.G.; Ascheim, D.D.; Casey DEJr Chung, M.K.; de Lemos, J.A.; Ettinger, S.M.; Fang, J.C.; Fesmire, F.M.; Franklin, B.A.; Granger, C.B.; Krumholz, H.M.; Linderbaum, J.A.; Morrow, D.A.; Newby, L.K.; Ornato, J.P.; Ou, N.; Radford, M.J.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Tommaso, C.L.; Tracy, C.M.; Woo, Y.J.; Zhao, D.X. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61, e78–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, D.D.; Bohula, E.A.; Morrow, D.A. Epidemiology and causes of cardiogenic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021, 27, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauridsen, M.D.; Rørth, R.; Lindholm, M.G.; Kjaergaard, J.; Schmidt, M.; Møller, J.E.; Hassager, C.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.; Køber, L.; Fosbøl, E.L. Trends in first-time hospitalization, management, and short-term mortality in acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock from 2005 to 2017: A nationwide cohort study. Am Heart J. 2020, 229, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, R.L.; Milano, C.A.; Smith, L.R.; White, W.D.; Rankin, J.S.; Glower, D.D. Prognosis and management of anterolateral myocardial infarction in patients with severe left main disease and cardiogenic shock. The left main shock syndrome. The left main shock syndrome. Circulation. 1993, 88(5 Pt 2), II65–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.H.; Smith, P.K. Coronary-Artery Bypass Grafting. N Engl J Med. 2016, 374, 1954–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, A.; Elzeneini, M.; Elgendy, I.Y.; et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting after acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023, 165, 672–683.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner, S.; Florian, A.; Ruel, M. Coronary artery bypass grafting in acute coronary syndromes: modern indications and approaches. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2024, 39, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Alviar, C.L.; Katz, S.D.; Hochman, J.S. Coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Am Heart J. 2020, 226, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulukutla, S.R.; Gleason, T.G.; Sharbaugh, M.; et al. Coronary Bypass Versus Percutaneous Revascularization in Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019, 108, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Akin, I.; Sandri, M.; et al. PCI Strategies in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 2419–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsky, M.D.; Morrow, D.A.; Proudfoot, A.G.; Hochman, J.S.; Thiele, H.; Rao, S.V. Cardiogenic Shock After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Review. JAMA. 2021, 326, 1840–1850, Erratum in JAMA. 2021, 326, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, T.D.; Tomey, M.I.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; et al. Invasive Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021, 143, e815–e829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Diepen, S.; Katz, J.N.; Albert, N.M.; et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017, 136, e232–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.; Stub, D.; Clark, D.J.; et al. Usefulness of transient and persistent no reflow to predict adverse clinical outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2012, 109, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Cassese, S.; Xhepa, E.; et al. Coronary no-reflow and adverse events in patients with acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention with current drug-eluting stents and third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024, 113, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davierwala, P.M.; Leontyev, S.; Verevkin, A.; et al. Temporal Trends in Predictors of Early and Late Mortality After Emergency Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2016, 134, 1224–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Gulack, B.C.; Loyaga-Rendon, R.Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: Data From The Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016, 101, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Kappetein, A.P.; Sabik, J.F.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes after PCI or CABG for Left Main Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 1820–1830, Erratum in N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1078. 10.1056/NEJMx200004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, N.R.; Mäkikallio, T.; Lindsay, M.M.; et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in the treatment of unprotected left main stenosis: updated 5-year outcomes from the randomised, non-inferiority NOBLE trial. Lancet. 2020, 395, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Bergmark, B.A.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in left main coronary artery disease: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2021, 398, 2247–2257, Erratum in Lancet. 2022, 399, 1606. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00701-2; Lancet. 2022, 400, 1304. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01944-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Webb, J.G.; et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 1999, 341, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; Assmann, S.F.; Sanborn, T.A.; Jacobs, A.K.; Webb, J.G.; Sleeper, L.A.; Wong, C.K.; Stewart, J.T.; Aylward, P.E.; Wong, S.C.; Hochman, J.S. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) trial. Circulation. 2005, 112, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omerovic, E.; Råmunddal, T.; Petursson, P.; Angerås, O.; Rawshani, A.; Jha, S.; Skoglund, K.; Mohammad, M.A.; Persson, J.; Alfredsson, J.; Hofmann, R.; Jernberg, T.; Fröbert, O.; Jeppsson, A.; Hansson, E.C.; Dellgren, G.; Erlinge, D.; Redfors, B. Percutaneous vs. surgical revascularization of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with multivessel disease: the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur Heart J. 2025, 46, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakaeen FG, Gaudino M, Whitman G, Doenst T, Ruel M, Taggart DP, Stulak JM, Benedetto U, Anyanwu A, Chikwe J, Bozkurt B, Puskas JD, Silvestry SC, Velazquez E, Slaughter MS, McCarthy PM, Soltesz EG, Moon MR; American Association for Thoracic Surgery Cardiac Clinical Practice Standards Committee; Invited Experts. 2021: The American Association for Thoracic Surgery Expert Consensus Document: Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021, 162, 829–850.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.; Park, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, C.W. Meta-Analysis Comparing the Risk of Myocardial Infarction Following Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Versus Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Multivessel or Left Main Coronary Artery Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019, 124, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Mejía, A.F.; Ortega-Armas, M.E.; Mejía-Rentería, H.; et al. Short-term clinical outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention of unprotected left main coronary disease in cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020, 95, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Ramasamy, A.; Brown, J.T.; et al. Treatment Strategies and Outcomes of Emergency Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2022, 177, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nasasra, A.; Hochadel, M.; Zahn, R.; et al. Outcomes After Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock (from the German ALKK PCI Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2023, 197, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, K.; Jain, V.; Hendrickson, M.J.; et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation With or Without Impella in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock. Am J Cardiol. 2022, 181, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.M.; Lipinski, J.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; et al. Simultaneous Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation and Percutaneous Left Ventricular Decompression Therapy with Impella Is Associated with Improved Outcomes in Refractory Cardiogenic Shock. ASAIO J. 2019, 65, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, F.; Schulte, C.; Pieri, M.; et al. Concomitant implantation of Impella® on top of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may improve survival of patients with cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Deswal, A.; et al. Contributory Risk and Management of Comorbidities of Hypertension, Obesity, Diabetes Mellitus, Hyperlipidemia, and Metabolic Syndrome in Chronic Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016, 134, e535–e578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwich, T.B.; Hernandez, A.F.; Dai, D.; Yancy, C.W.; Fonarow, G.C. Cholesterol levels and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008, 156, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Lupi, L.; et al. Prognostic significance of serum total cholesterol and triglyceride levels in patients hospitalized for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (from the EVEREST Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013, 111, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Shi, Z.; Pang, X. Association between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e044668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papolos, A.I.; Kenigsberg, B.B.; Berg, D.D.; et al. Management and Outcomes of Cardiogenic Shock in Cardiac ICUs With Versus Without Shock Teams. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.M. Bayesian Interpretation of the EXCEL Trial and Other Randomized Clinical Trials of Left Main Coronary Artery Revascularization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020, 180, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, N.R.; Mäkikallio, T.; Lindsay, M.M.; et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in the treatment of unprotected left main stenosis: updated 5-year outcomes from the randomised, non-inferiority NOBLE trial. Lancet. 2020, 395, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2016-2020 | Left Main STEMI & PCI | Left Main STEMI & CABG | P-value | Odds Ratio (C.I) |

| Total Population | 700 | 350 | ||

| Age | 0.47 | |||

| Mean±SD | 66.42±11.89 | 65.11±12.63 | ||

| Median(IQR) | 66(59-74.5) | 66(57-74) | ||

| LOS | <0.001 | |||

| Mean±SD | 7±9 | 14±10 | ||

| Median(IQR) | 4(1-9) | 10.5(7-21) | ||

| Total Charges $ | 0.006 | |||

| Mean | 284432 | 423202 | ||

| Median | 224667 | 307426 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62.86% | 68.57% | REF | |

| Female | 37.14% | 31.43% | 0.41 | 1.29(0.70-2.37) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 58.82% | 66.67% | REF | |

| Black | 11.03% | 11.11% | 0.81 | 1.12(0.42-3.01) |

| Hispanic | 14.71% | 9.52% | 0.27 | 1.75(0.64-4.76) |

| Asian/Pac Isl | 5.88% | 3.17% | 0.37 | 2.10(0.41-10.68) |

| Native American | 2.21% | 0.00% | NA | 1 |

| Others | 7.35% | 9.52% | 0.81 | 0.87(0.29-2.64) |

| Mortality | 55.00% | 15.71% | <0.001 | 6.56(3.19-13.46) |

| Diabetes | 40.71% | 35.71% | 0.48 | 1.24(0.68-2.23) |

| Smoking | 21.43% | 21.43% | 1 | 1.00(0.49-2.03) |

| CKD | 25.71% | 24.29% | 0.83 | 1.08(0.53-2.18) |

| COPD | 10.71% | 12.86% | 0.65 | 0.81(0.33-1.99) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 57.86% | 57.14% | 0.92 | 1.03(0.58-1.83) |

| Alcohol | 5.00% | 2.86% | 0.48 | 1.79(0.36-9.01) |

| ECMO | 9.29% | 5.71% | 0.38 | 1.69(0.52-5.46) |

| IABP | 37.86% | 71.43% | <0.001 | 0.24(0.13-0.45) |

| Impella | 42.14% | 11.43% | <0.001 | 5.65(2.55-12.51) |

| Peripheral Vascular Diseases | 5.00% | 5.71% | 0.83 | 0.87(0.24-3.17) |

| History of Cardiomyopathy | 0.00% | 1.43% | NA | 1 |

| History of Systolic Heart Failure | 40.71% | 38.57% | 0.77 | 1.09(0.61-1.97) |

| Cachexia | 1.43% | 0.00% | NA | 1 |

| Morbid Obesity | 4.29% | 8.57% | 0.22 | 0.48(0.15-1.55) |

| Obesity | 8.57% | 10.00% | 0.74 | 1.19(0.43-3.24) |

| Chronic Liver Disease | 27.14% | 21.43% | 0.36 | 1.37(0.70-2.68) |

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 24.29% | 31.43% | 0.29 | 0.70(0.36-1.35) |

| Valvular Heart Disease | 10.71% | 17.14% | 0.18 | 0.58(0.26-1.30) |

| History of Stroke | 0.71% | 0.00% | NA | 1 |

| Acute Lactic Acidosis | 42.14% | 37.14% | 0.48 | 1.23(0.69-2.20) |

| Cardiac Arrest | 12.86% | 7.14% | 0.19 | 1.92(0.73-5.07) |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 63.57% | 37.14% | 0.001 | 2.95(1.59-5.48) |

| Renal Replacement Therapy | 10.00% | 11.43% | 0.75 | 0.86(0.34-2.18) |

| Presence of Aortocoronary Bypass Graft | 3.57% | 1.43% | 0.4 | 2.56(0.29-22.66) |

| Right Ventricular Infarction | 2.14% | 1.43% | 0.72 | 1.51(0.15-15.03) |

| Outcome | PCI Group | CABG Group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 55.0% | 15.7% | <0.001 ★ |

| Length of stay (days) | 7 ± 9 (median 4 [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]) | 14 ± 10 (median 10.5 [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]) | <0.001 ★ |

| Total hospital charges | $284,432 (median $224,667) | $423,202 (median $307,426) | 0.006 ★ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).