1. Introduction

Infertility is a growing issue, affecting between 12.6% and 17.5% of couples of reproductive age worldwide [

1]. In around 15% of cases, the cause of infertility remains unknown even after a thorough investigation of both partners [

2]. In these cases, “infertility of unknown origin” or “unexplained infertility” (UI) is diagnosed. Currently, there is no standardized management algorithm for couples with UI in order to take targeted actions to improve their fertility outcomes.

Recent studies have investigated various biomarkers to uncover the underlying causes and mechanisms that could be the real underlying reason of infertility for patients, diagnosed with unexplained infertility [

3,

4]. Among them is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is a crucial mediator of endothelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, along with influencing vascular permeability [

5]. The existing data suggests that VEGF in woman’s body also serves in embryo implantation, and changes in its expression, such as VEGF polymorphisms, might contribute to both infertility and pregnancy-related complications [

6]. Therefore, comprehensive analysis of VEGF as a potential biomarker in unexplained infertility and related reproductive disorders for women could provide valuable insights into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of cases previously classified as idiopathic.

VEGF is also an angiogenic factor and a protein, essential for vascular function, tissue repair, and embryonic development. This protein has an influence for pathologies ranging from cancer to chronic inflammatory diseases like asthma [

5,

7,

8]. In the female reproductive system, VEGF plays a crucial role during pregnancy in vasculogenesis, the formation of the embryonic circulatory system, as well as angiogenesis – the development of blood vessels from existing vasculature. Signal transduction occurs when VEGF binds to tyrosine kinase receptors, triggering a cascade that leads to endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and the formation of new blood vessels [

7,

8,

9]. Physiological angiogenesis primarily occurs in wound healing and during the female reproductive cycle [

7]. In this context, the investigation of VEGF as a biomarker in reproductive health is essential, especially given the complex and multifactorial nature of female infertility. As VEGF is regulated by several factors – including atopy, which has also been implicated in infertility – it needs to be carefully considered in clinical assessments of reproductive well-being [

10].

Sensitization, which is a heightened immune response to environmental allergens, has been linked to unexplained infertility through its impact on the immune system and uterine environment. Increased levels of inflammatory markers, such as IgE and cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α, can disrupt endometrial receptivity, making implantation more difficult [

11]. Chronic low-grade inflammation, driven by allergens may further alter vascular factors like VEGF, which are crucial for healthy blood vessel formation in the uterus [

12]. Therefore, the aim of our study was to analyze VEGF’s potential as a biomarker for unexplained infertility for women, taking into consideration its multifaceted nature and challenging interpretation, and to evaluate the possible connections between VEGF concentrations, infertility and atopic sensitization in women. Additionally, in order to establish the range of “normal” serum VEGF concentrations for healthy individuals and to facilitate comparison with the data obtained in our study, we have performed a literature review of reported serum VEGF value ranges in scientific literature published between 1998 and 2024.

2. Materials and Methods

A prospective observational study was conducted. 70 patients, who referred to the Centre of Innovative Allergology in Vilnius, Lithuania were included in the study: 51 women with unexplained primary infertility and 19 fertile women. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in

Table 1.

Vilnius Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the implementation of this study (document number 2024/2-1558-1026). Individuals who agreed to participate in this study signed written informed consent forms.

The dataset consisted of the demographic data of the subjects, ALEX2 macroarray test results, concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in blood serum determined by the enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) method as well as gynecological and allergological-immunological anamnesis of the participants. Gynecological and allergological-immunological anamnesis included information about previously diagnosed pathologies, which could have an impact on female fertility, as well as the results of previously performed tests to diagnose gynecological and allergological-immunological pathologies. Venous blood for ALEX2 and ELISA tests was drawn via venipuncture into Vacutainer tubes without anticoagulant for serum collection. The blood was left to clot at room temperature, centrifuged, and the separated serum was frozen at -80°C.

Serum VEGF concentration was measured in duplicate using a commercial ELISA kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The assay had a sensitivity of less than 5 pg/mL of VEGF. Optical density at 450 nm was measured using a BioTek ELx800 plate reader. VEGF concentrations were determined by linear regression from a standard curve generated with the VEGF standards provided in the kit.

The sensitization of the subjects was analyzed using the ALEX² macroarray test (MacroArray Diagnostics GmbH, Austria), an ELISA-based immunoassay. The ALEX² test includes 295 antigens (117 extract allergens and 178 molecular components) bound to nanoparticles and arrayed on a solid surface. In the assay, particle-bound allergens interact with specific IgE antibodies in the patient's serum sample. After incubation, nonspecific IgE is removed by washing. An enzyme-labeled anti-human IgE detection antibody is then added, forming complexes with the particle-bound specific IgE. After a second wash, a substrate is introduced, producing an insoluble colored precipitate. The reaction is stopped with a blocking reagent, and the precipitate amount correlates with the specific IgE concentration. Image acquisition and analysis were performed using the ImageXplorer device, and results were processed with MADx’s RAPTOR SERVER Analysis Software. IgE levels were reported in kUA/L, with total IgE in kU/L. Sensitization was defined by an IgE level of 0.3 kUA/L or higher.

According to ALEX² macroarray test results and their clinical history, all patients were additionally allocated into three subgroups by „allergy status“: non-allergic (negative ALEX² macroarray test results), atopic (positive ALEX² macroarray test results without clinical history of allergy to respective allergens) and allergic (positive ALEX² macroarray test results and previous clinical history of allergy to respective allergens).

Scientific literature review of articles published between 1998 and 2024 reporting serum VEGF value ranges was performed in order to establish the range of “normal” serum VEGF concentrations for healthy individuals and to facilitate comparison with the data obtained in our study. The articles were only included in the review if they reported VEGF values in of the blood serum and if they featured a comparison of VEGF values between healthy and diseased individuals.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to evaluate the normality of the data. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test with a two-tailed hypothesis and the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to assess differences between patient groups. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test was employed to evaluate ordered differences among multiple groups. Categorical data variables were compared using the Fisher’s Exact test . Logistic regression combined with ROC curves was used to evaluate the classification performance of various models. The optimal cut-off value for serum VEGF concentration was determined using Youden’s J statistic. All analyses were conducted using the R program (version 4.3.3) with the Rcmdr package (version 2.9-2), and Python version 3.11.4 (Python Software Foundation), with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

The total of 70 women were included in the study: 51 women with primary unexplained infertility (UI) and 19 fertile women. 6 women with UI did not agree to disclose their personal data, therefore, only their serum VEGF concentrations and ALEX² macroarray test’s results were included in this study, while analysis of demographical data and other infertility related factors was only performed for 45 women with primary UI. The average age of the subjects was 33.58 (SD±5) years with a minimum of 18 and a maximum of 43 years old. The average age of fertile women was 32.89 (SD±6.71) and the average age of women with UI – 33.87 (SD±4.19). Of 64 women included in this study with known anamnesis, 35 had additional chronic, allergic or autoimmune diseases, of which 7 were fertile and 28 were infertile, while only 29 women did not have any comorbidities. Infertile women were diagnosed with autoimmune diseases statistically significantly more frequently in comparison with fertile women (10 vs 0 (p=0.026)).

6 subjects from the fertile group and 18 from the infertile group were diagnosed with allergic diseases. The most common allergic diseases in UI group were allergic rhinitis (9 (20.00%) and atopic dermatitis (9 (20.00%), in fertile women group – atopic dermatitis (5 (26.32%)). There was no statistically significant difference between the prevalence of allergic diseases in general between fertile and infertile women in the sample of our study (p=0.583) as well as between the prevalence of specific allergic diseases, such as allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, urticaria, bronchial asthma etc. Table A1

In order to determine the participants allergy status, ALEX² macroarray tests were performed for all participants. Allergy was confirmed if a correlation between hypersensitization and clinical symptoms for a specific allergen was confirmed. If no clinical history of allergy was determined for a subject, while ALEX² indicated a sensitization, atopy was diagnosed. The associations between allergy and atopy status, ALEX² results and serum VEGF concentrations were analyzed.

A total of 37 subjects were diagnosed with sensitization to at least one allergen component. Among these, 20 had confirmed allergies as determined by the ALEX² macroarray test and showed clinical manifestations. Meanwhile, 16 subjects were diagnosed with sensitization but either did not exhibit clinical symptoms or lacked sufficient clinical data for interpretation; these individuals were categorized into the atopic patient group. There were no statistically significant differences between the prevalence of allergy and atopy between fertile and infertile women, however, women with UI were diagnosed with confirmed allergy slightly more frequently in comparison with fertile women: 15 (33.33%) infertile vs 5 (26.32%) fertile (p=0.769).The median VEGF blood serum concentration of the whole sample group was 111.6 pg/ml (IQR=134.2). The median serum VEGF concentration for women, diagnosed with infertility of unknown origin, was higher in comparison with fertile women, 128.6 pg/ml vs 82.5 pg/ml, p=0.152. Serum VEGF levels in women with unexplained infertility ranged from 0.0 pg/ml to 501.7 pg/ml, while levels in fertile women ranged from 5.1 pg/ml to 443.9 pg/ml. Also, VEGF values of different allergy status subgroups were compared.

Table 2.

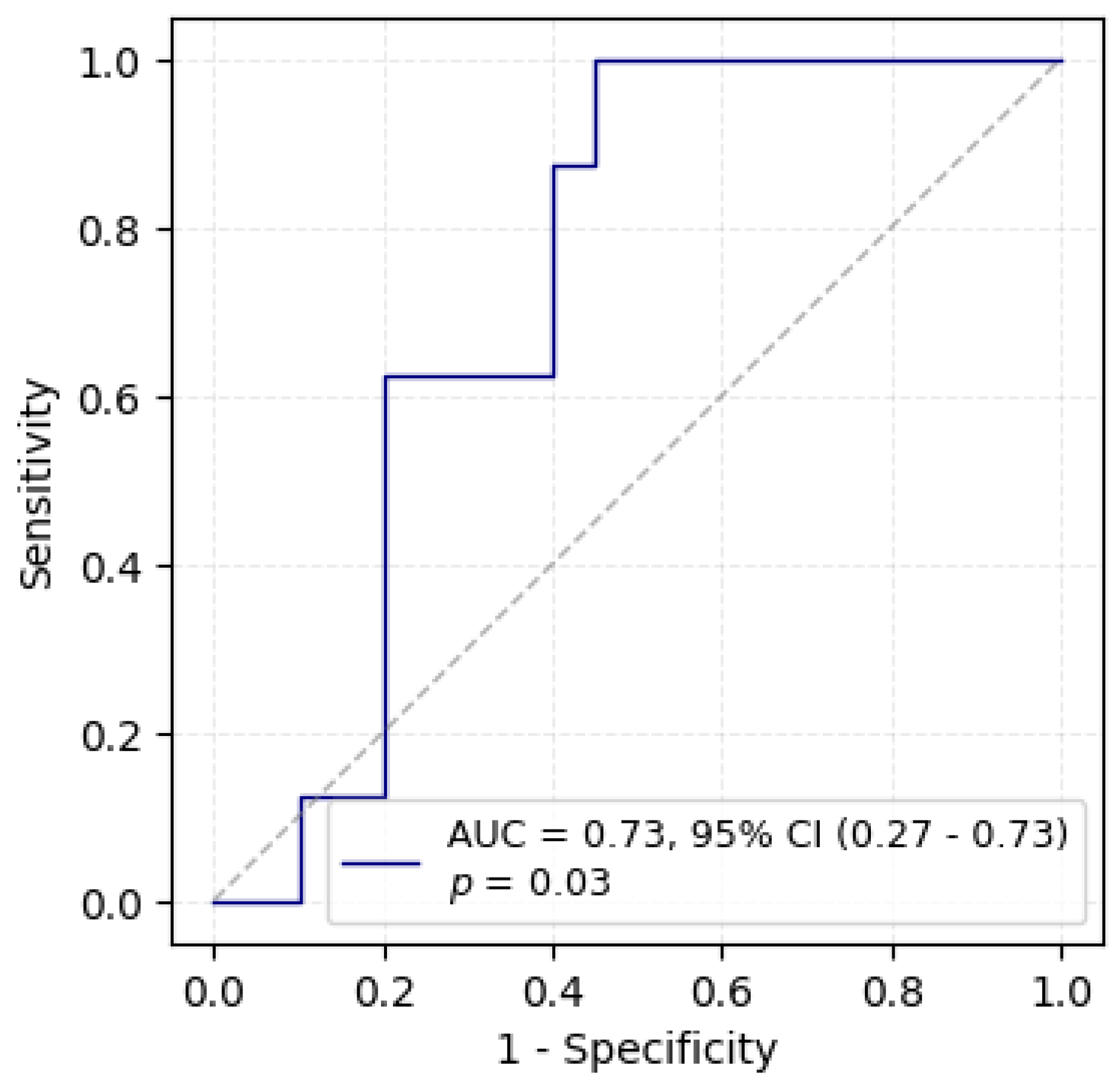

When the data was introduced into the logistic regression model, it was indicated that serum VEGF level exhibits a moderate ability to discriminate between fertile and infertile women with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.73. The optimal cut-off value, determined using Youden’s J statistic, was identified as 122.23 pg/mL, corresponding to a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 55%. These findings suggest that serum VEGF concentration may have utility as a classifier for fertility status, given its overall ability to distinguish between fertile and infertile women.

Figure 1.

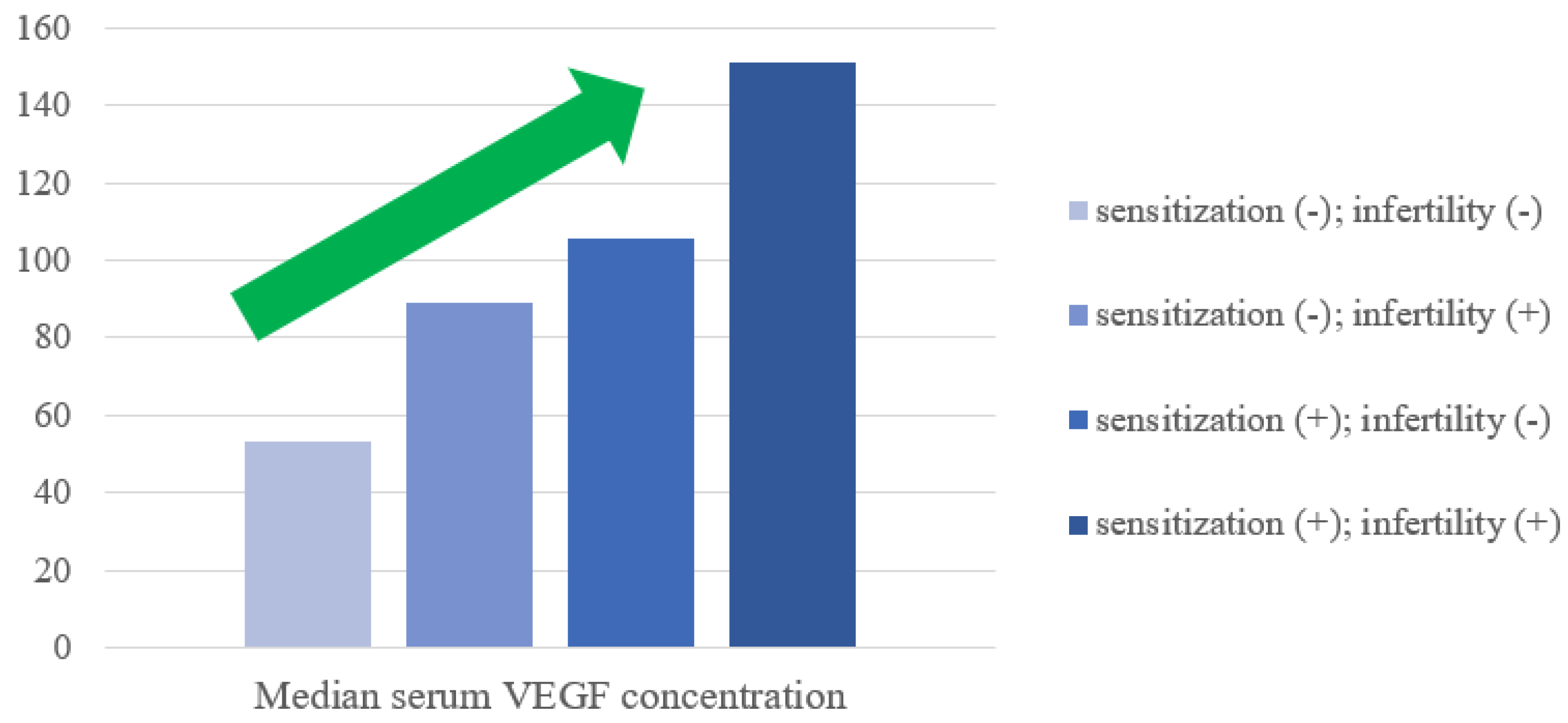

Median serum VEGF values were compared between sensitized women, according to ALEX² macroarray test and non-sensitized women considering whether sensitization may also determine higher levels of serum VEGF concentration. Firstly, it was observed that the median serum VEGF concentration of women, who were sensitized to at least one allergen, was statistically significantly higher in comparison with non-sensitized women (115.9 pg/ml vs 85.7 pg/ml, accordingly), p=0.028. Secondly, when fertile and infertile women were compared according to their sensitization status, it was determined that in both, fertile and infertile groups, serum VEGF concentrations were higher in the sensitized group in comparison with non-sensitized group.

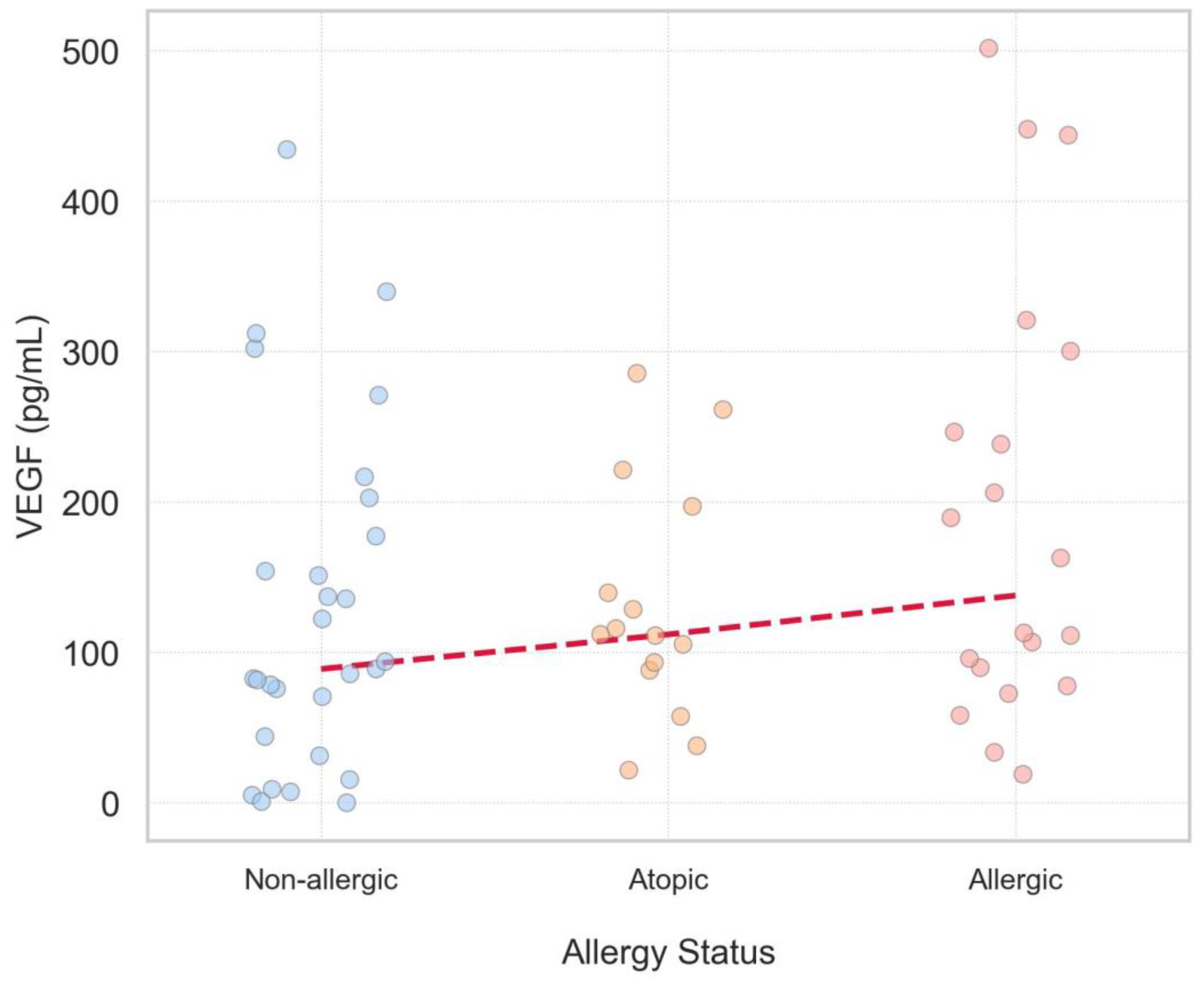

When VEGF values were further compared within 3 subgroups of women: non-allergic, atopic and allergic, serum VEGF levels of infertile women were observed to be higher in all 3 subgroups in comparison with corresponding results of the fertile group, however, the differences were too sophisticated to reach the statistical threshold. In addition, to determine if VEGF levels have the tendency to be higher with the severity of allergic status, a stepwise rise of VEGF levels was noted among the non-allergic, sensitized, and allergic subgroups. The increasing trend was statistically supported by the Jonckheere-Terpstra test (JT = 791.5, p = 0.045), suggesting a potential link between VEGF level and allergy status.

Figure 2.

Notably, as higher serum VEGF concentrations were observed for women who were sensitized and for infertile women, the combination of both these features (detected sensitization to at least one allergen component and a diagnosis of unexplained infertility) were established to increase serum VEGF values even more.

Figure 3

According to the ALEX

2 macroarray test, the most frequently detected sensitizations for all subjects were to pets’, tree pollen and fish and seafood allergen groups: 19 (27.1%) cases, 15 (21.4%) and 15 (21.4%) cases, accordingly. Sensitization to house dust mites (HDM) and grass pollen groups was also frequently detected for all subjects with 14 (20.0%) cases of sensitization for each of these allergen groups. However, the most common allergies (confirmed by a combination of ALEX

2 test results and clinical history) for all subjects were diagnosed to tree pollen (17 (26.56%)) and cat (16 (25.0%)) allergens.

Table 3. Moreover, women with UI were observed to be more frequently sensitized to Fel d 1 (13 (18.6%)) vs (3 (4.3%)) and Der p 23 (7 (10.0%) vs 1 (1.43%) in comparison with fertile women of our study.

An interesting observation was discovered when the serum VEGF values were compared between women of all subgroups, who were sensitized to specific allergen groups or components. Firstly, women who were sensitized to pets’ allergens group, were found to have statistically significantly higher serum VEGF concentrations 206.1 pg/mL in comparison with women who were not sensitized to pets’ allergens (93.9 pg/mL) (p=0.003). Secondly, women who were sensitized to weed pollen, were found to have statistically significantly higher serum VEGF concentrations (206.1 pg/mL) in comparison with women who were not sensitized to weed pollen (106.8 pg/mL) (p=0.043).

Women who were sensitized to the cat allergen component Fel d 1 had a significantly higher serum concentration of VEGF, with a median level of 200.0 pg/mL, compared to women who were not sensitized to this allergen. The median level for the non-sensitized group was 100.6 pg/mL, and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.019). Moreover, women, who were sensitized to other pet’s allergens, such as cat’s allergens Fel d 4 (238.4 vs 111.2 pg/mL), Fel d 7 (238.4 vs 111.2 pg/mL) and dog’s allergens Can f 1 (214.0 vs 109.0 pg/mL), Can f 5 (205.4 vs 109.0 pg/mL), Can f 6 (214.0 vs 111.2 pg/mL) also had higher median VEGF levels than non-sensitized ones. The highest serum VEGF concentrations of all (501.7 pg/mL and 447.1 pg/mL) were found for women who were both diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and both sensitized to multiple allergen components, of which both were sensitized to: tree pollen (Aln g 1, Bet v 1, Cor a 1.0103, Fag s 1), pets (Can f 1), weed pollen and fruits’ allergen groups.

Additionally, the relationship between serum VEGF concentration and autoimmune diseases in subjects’ clinical history was analyzed. The median of serum VEGF was found to be significantly lower in patients diagnosed with thyroid nodules (N=3, median VEGF: 15.4 pg/ml) in comparison with patients without thyroid nodules (N=61, median VEGF: 112.9 pg/ml) (p=0.045). Moreover, though VEGF values were determined to be higher for women with unexplained infertility and women with UI were diagnosed with autoimmune diseases statistically more frequently, according to our study data, no significant tendencies have been observed between levels of serum VEGF concentrations and any other specific chronic or autoimmune disease. Moreover, none of the specific autoimmune, allergic or chronic diseases were diagnosed statistically significantly more frequently for the UI patients in our study.

To establish the range of “normal” serum VEGF concentrations and to facilitate comparison with the data obtained in our study, we analyzed 25 papers published between 1998 and 2024. These papers reported serum VEGF value ranges across various diseases, including oncologic conditions, allergic diseases, as well as chronic, autoimmune, and inflammatory diseases.

Table 4.

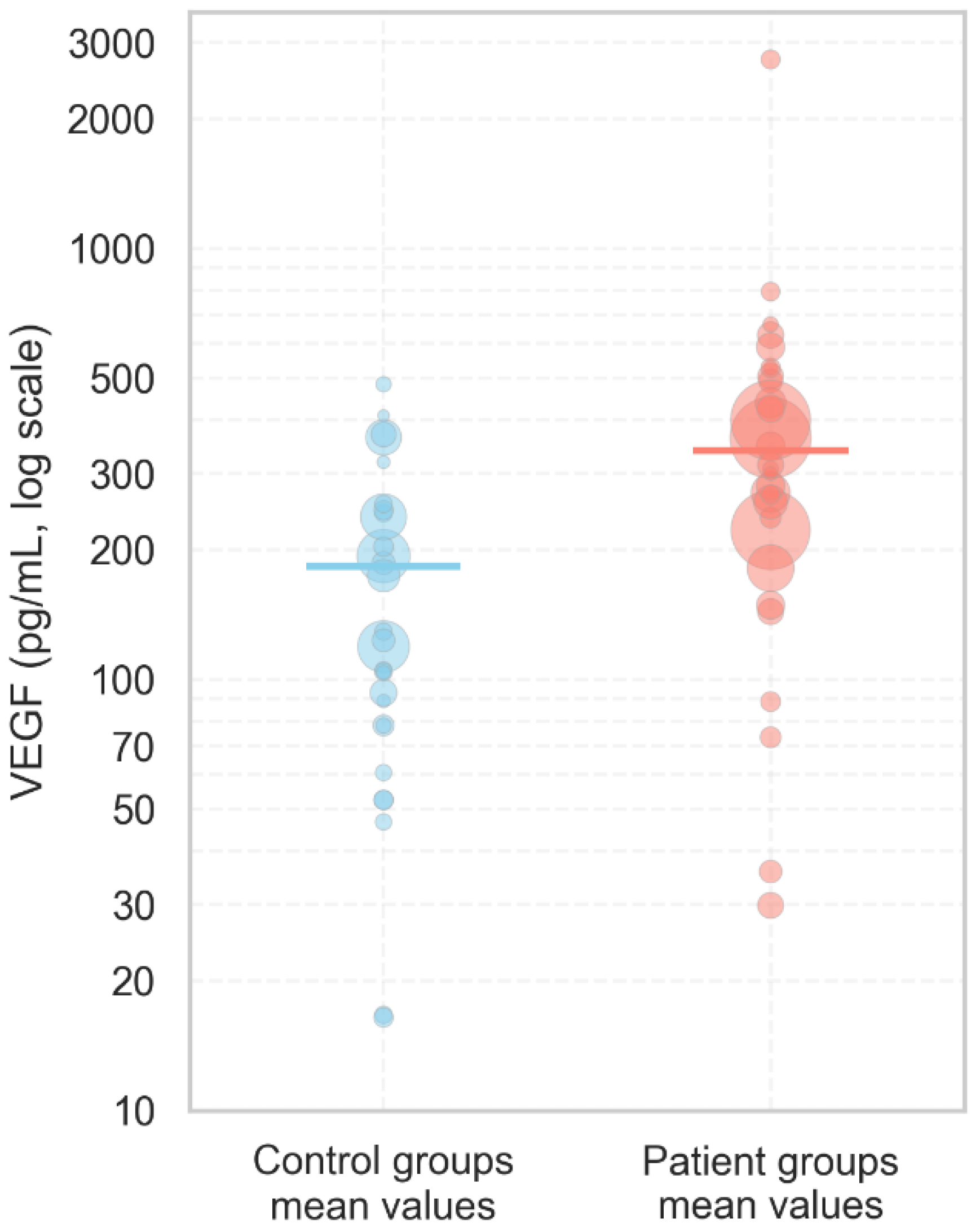

Based on our thorough scientific analysis of 25 distinct studies, analyzing VEGF concentrations in blood serum, we determined that average VEGF levels in diseased subjects ranged from 29.9 pg/ml to 793 pg/ml, while in healthy controls, the average range was from 16.4 pg/ml to 483.5 pg/ml. The weighted mean VEGF concentration was higher in the diseased patients’ group (338.83 pg/ml) than in the control group (182.68 pg/ml).

Figure 4.

The distribution of serum VEGF concentrations in patients and control groups according to our analyzed literature articles published between 1998 and 2024. Each dot represents the mean VEGF value reported in an individual study, with the size of the dot proportional to the study's sample size, reflecting the relative weight of each study. Solid horizontal lines indicate the weighted mean VEGF concentration for each group, calculated across all studies.

Figure 4.

The distribution of serum VEGF concentrations in patients and control groups according to our analyzed literature articles published between 1998 and 2024. Each dot represents the mean VEGF value reported in an individual study, with the size of the dot proportional to the study's sample size, reflecting the relative weight of each study. Solid horizontal lines indicate the weighted mean VEGF concentration for each group, calculated across all studies.

To assess whether the VEGF concentrations observed in fertile women (control group) in our study align with values reported for healthy individuals, we compared our measurements with control data available in the literature. The serum VEGF concentrations in the fertile group (median: 82.5 pg/mL; IQR: 71.7 pg/mL) appeared to be comparable to those reported for healthy controls in published studies (median of reported means: 123 pg/mL; IQR: 164.7 pg/mL). This suggests that the VEGF levels in our control group fall within a physiologically normal range and may be suitable for subsequent statistical analysis and comparison with the infertile patient group.

The most elevated levels of VEGF were measured for patients with oncologic pathologies – in these cases the values of serum VEGF were often double or triple than those seen in healthy controls. Additionally, in a meta-analysis published in 2007 by

Kut et al., this finding was also supported by determining that the concentration of VEGF in blood serum was higher in patients with various oncologic diseases [

13]. For example, in

Kut et al. meta-analysis, serum VEGF level ranges for patients with breast cancer were registered to be about twice as high as those in healthy controls (92–390 vs 17–287 pg/ml), serum VEGF levels of prostate cancer patients were found to be 2–3 times higher in comparison with healthy controls (129–323 pg/ml for prostate cancer patients vs 17–171 pg/ml for healthy controls) and serum VEGF levels were found to be approximately twice as high in colorectal cancer patients in comparison with healthy controls (66–563 pg/ml for colorectal cancer patients vs 173–391 pg/ml for healthy individuals) [

13].

In inflammatory diseases, such as bronchial asthma, VEGF levels were also detected to be similarly elevated. For example, in a study by

Gomulka et al. VEGF levels were determined to be significantly higher in patients with bronchial asthma in comparison with healthy controls (314.35 pg/ml vs 246.6 pg/ml, p = 0.0131) [

27].

4. Discussion

In our study, we observed that women diagnosed with unexplained infertility exhibited higher median VEGF levels than fertile controls. Additionally, autoimmune diseases were significantly more frequent in women with UI, though no clear associations were found between individual autoimmune diagnoses and serum VEGF levels. Nevertheless, the highest median serum VEGF concentrations were found for infertile women who were diagnosed with chronic diseases, with the highest serum VEGF level being 501.7 pg/mL.

Elevated serum VEGF levels were also significantly associated with allergic sensitization confirmed by ALEX

2 macroarray test, with the highest concentrations found in women who were both sensitized (confirmed by ALEX

2 test) and diagnosed with UI. A statistically significant upward trend in VEGF was observed with increasing allergy severity – rising from non-allergic to atopic, and highest in allergic subjects - pointing towards a possible association between allergy status and elevated level of VEGF. Similar findings were reported by

Tedeschi et al. in patients with chronic urticaria, where VEGF levels correlated with disease severity, supporting a link between VEGF and allergy status [

37]. Women sensitized to pet allergens—especially to

Fel d 1—had significantly elevated VEGF levels. This may indicate that long-lasting exposure to some environmental allergens, leading to continuous immune stimulation, may upregulate VEGF expression. This is supported by studies showing that allergen-stimulated mast cells produce VEGF through leukotriene B4 receptor–2 signaling [

38], and that environmental toxicants activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway (e.g., TCDD) enhance VEGF expression in bronchial epithelial cells [

39]. Chemical allergens have also been shown to stimulate lymphagiogenic VEGF production by human keratinocytes [

40].

Therefore, our results additionally support the hypothesis that elevated serum VEGF level in women with unexplained infertility, particularly those with allergic sensitization, may be a marker for a state of chronic low-grade inflammation or immune dysregulation that interferes with reproductive function. Very recent scientific findings highlight the complex interplay between VEGF, immune system components, and inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of reproductive disorders [

41]. While elevated VEGF may not be an immediate cause of infertility, it may as well be an indirect indicator of latent pathophysiologic processes that require further investigation.

One of the main challenges our study has encountered was interpreting VEGF levels and establishing the “normal” serum VEGF value range due to the lack of standardized serum VEGF reference ranges altogether. This currently poses a significant problem for researchers and physicians when evaluating serum VEGF concentration and its significance in different clinical situations. While some equipment manufacturers suggest a reference range of 62–707 pg/ml, there is no universally accepted norm, and VEGF levels are known to vary significantly with pathological conditions [

14,

42]. Moreover, the medical publications analyzing only female VEGF levels are scarce.

Our results are consistent with those of

Atalay et al., who reported significantly elevated VEGF in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage compared to healthy fertile women (210.3 ± 108.2 pg/mL vs 123.9 ± 18.8 pg/mL) [

43], supporting VEGF's potential role as a marker of subclinical inflammation or vascular dysregulation that results in reproductive failure.

Similarly, in the context of assisted reproduction technologies(ART), specific VEGF levels have been associated with both, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), which is one of the most common complications of ART, as well as implantation success itself. However, while elevated VEGF levels are not always necessarily pathogenic, as in cases of OHSS, elevation of this biomarker may be indicative of systemic inflammation or vascular reactivity [

44]. Our results support the thesis that increased levels of VEGF may reflect an inflammatory state influenced by associated conditions such as atopy or chronic illness, that may be significant for the impaired reproductive function.

In allergic diseases, VEGF contributes to Th2-type inflammation, promoting asthma-like phenotypes [

45], recurrent wheezing [

46], and nasal obstruction and inflammation in response to allergens [

47]. In chronic diseases, VEGF is upregulated in response to hypoxia via HIF-1α–driven signaling, leading to angiogenesis and increased vascular permeability [

48,

49]. ]. In oncologic conditions, serum VEGF levels also increase mainly due to hypoxia-induced signaling and tumor-driven angiogenesis. Rapid tumor growth causes hypoxia, which activates HIF-1 and upregulates VEGF to support vascularization and metastasis [

50]. Oxidative stress under hypoxic conditions stabilizes HIF-1α, further enhancing VEGF expression through the NF-κB signaling pathway, which also promotes inflammation, tumor progression and angiogenesis [

51,

52]. Cytokines such as TGF-β1, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-13 promote VEGF production, contributing to neovascularization and inflammationin conditions like allergic conjuctivitis and asthma [

40,

53]. Additionally, PI3K/Akt pathway is crucial in regulating VEGF expression. In vivo studies show that VEGF inhibition reduces TGF-β1 levels and fibrosis, indicating a feedback loop between VEGF and TGF-β1 via PI3K/Akt signaling [

54]. VEGF-C also contributes to lymphangiogenesis in skin sensitization [

40]. Elevated VEGF levels, which were observed for our subjects sensitized to pets, and particularly cats, further support the notion that persistent antigen exposure in chronic sensitization processes—such as unavoidable pet-related sensitization—may contribute to increased VEGF concentrations.

To sum up the above mentioned complex pathophysiological pathways in each of which VEGF plays a crucial role, the absence of clear norms makes it difficult to determine what constitutes "normal" VEGF level range, especially in conditions as varied as infertility, cancer, and allergic diseases, where VEGF expression may be affected by a complex of underlying factors [

14,

42].

From a reproductive perspective, based on it’s mode of action, VEGF is a key mediator of increased vascular permeability, negatively affecting oocyte maturation and follicular development in cases of OHSS [

55,

56,

57]. Additionally, elevated VEGF levels in follicular fluid has been correlated with lowered ovarian reserve and oocyte maturation rates.This is supported by a negative correlation between VEGF levels and the number of oocytes retrieved, as well as peak estradiol levels in the studies published by

Wu et al. These factors are crucial for successful fertilization and embryo development [

56,

58].

However, other studies (e.g.,

Monteleone et al.) suggest positive associations of higher VEGF levels with better perifollicular perfusion, which can lead to improved oocyte fertilization rates and and embryo quality [

59]. However, imbalanced VEGF levels may impair endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation—processes in which VEGF also play an important role—thereby contributing to implantation failure [

60].

Friedman et al. and

Asimakopoulos et al. reported that elevated VEGF levels in follicular fluid and blood serum, respectively, were associated with lower IVF success rates [

58,

61].

Overall, VEGF is a critical inflammatory biomarker involved in key reproductive processes, including oocyte maturation, endometrial receptivity, and endometrial remodeling and regeneration during each menstrual cycle [

62]. Both over- and underexpression can have negative reproductive consequences.

Nevertheless, given VEGF's involvement in chronic diseases, allergies, and cancer, elevated VEGF levels may not directly cause female infertility but rather reflect a complex interplay of coexisting pathologies that indirectly affect reproductive function. VEGF could also serve as a biomarker of underlying processes such as oxidative stress, which may be influenced by conditions like endometriosis or hypoxia linked to allergies and chronic disease [

27,

46,

47,

63,

64]. In this context, increased VEGF may not impair fertility directly but instead signal an underlying condition requiring further investigation.

Although serum VEGF ranges vary, our review found consistently higher VEGF levels in diseased individuals than in healthy controls. Similarly, women with unexplained infertility in our study showed higher median VEGF levels than fertile women, including differences between sensitized and non-sensitized subgroups. However, the small sample size limited statistical significance. These findings suggest that while VEGF may be involved in reproductive processes, its biomarker potential in unexplained infertility is limited due to the condition’s multifactorial nature.

Further research is needed to clarify VEGF’s role in female reproductive health, evaluate the impact of comorbidities, and assess potential gender-related differences. The absence of female-specific VEGF reference values presents a diagnostic challenge, highlighting the need for gender-dependent normative data.

5. Conclusions

Our study determined that women with UI, particularly those with allergic sensitization, had elevated serum VEGF levels in comparison with fertile women. Sensitization to pet allergens—especially cat allergen Fel d 1—was associated with the highest VEGF concentrations, and VEGF levels increased progressively with allergy status: non-allergic > atopic > allergic. Additionally, women with UI were more frequently diagnosed with autoimmune diseases. These findings suggest that VEGF may reflect broader immunological dysregulation relevant to fertility.

Literature analysis confirmed substantial variability in serum VEGF levels between healthy individuals and those with oncological or inflammatory diseases. Importantly, the VEGF values observed in our control group aligned with those reported for control groups in the literature, suggesting that our defined “normal” range may be appropriate for subsequent statistical analysis.

Further research is essential to determine whether elevated serum VEGF levels could directly contribute to specific infertility-related mechanisms or whether detected VEGF levels merely reflect an individual’s overall disease burden, with chronic conditions or allergic sensitization and their associated inflammatory environment being the primary contributors to reduced fertility. If VEGF is confirmed to be directly involved in infertility pathogenesis, it could serve as a valuable biomarker for identifying underlying causes of infertility that are currently categorized as unexplained. However, even if VEGF is not found to have a direct effect on female fertility or to reliably pinpoint a specific infertility-causing condition in future in-depth research, its elevated levels may still indicate a heightened inflammatory or immune-activated state that could adversely affect reproductive function, given the critical role of well-balanced VEGF levels for optimal fertility out-comes.

Given its association with both allergic sensitization and unexplained infertility, VEGF testing in women with UI—especially in the presence of atopy—can already serve as a useful tool for prompting broader clinical evaluation. It can help identifying coexisting chronic, autoimmune, or inflammatory conditions that are potentially contributing to reduced fertility. Even if not directly causal, elevated VEGF reflect a physiologically unfavorable environment for conception, thereby highlighting women who could benefit from targeted diagnostic work-up and potentially more personalized management strategies. Further in-depth research is essential to determine the potential direct role of VEGF in infertility.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Njagi P, Groot W, Arsenijevic J, Dyer S, Mburu G, Kiarie J. Financial costs of assisted reproductive technology for patients in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Open. 2023 Mar 1;2023(2):hoad007. [CrossRef]

- Carson SA, Kallen AN. Diagnosis and Management of Infertility. JAMA. 2021 Jul 6;326(1):65–76.

- Lu L, Lu Y, Zhang L. Regulatory T Cell and T Helper 17 Cell Imbalance in Patients with Unexplained Infertility. Int J Womens Health. 2024;16:1033–40. [CrossRef]

- Abdulslam Abdullah A, Ahmed M, Oladokun A, Ibrahim NA, Adam SN. Serum leptin level in Sudanese women with unexplained infertility and its relationship with some reproductive hormones. World J Biol Chem. 2022 Nov 27;13(5):83–94. [CrossRef]

- Apte RS, Chen DS, Ferrara N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell. 2019 Mar 7;176(6):1248–64. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Yi H, Li TC, Wang Y, Wang H, Chen X. Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in Human Embryo Implantation: Clinical Implications. Biomolecules. 2021 Feb 10;11(2):253. [CrossRef]

- Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004 Dec;56(4):549–80.

- Yang Y, Cao Y. The impact of VEGF on cancer metastasis and systemic disease. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2022 Nov 1;86:251–61. [CrossRef]

- 9. Duffy AM, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Harmey JH. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Role in Non-Endothelial Cells: Autocrine Signalling by VEGF. In: Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet] [Internet]. Landes Bioscience; 2013 [cited 2024 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6482/.

- Gomułka K, Mędrala W. Serum Levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Platelet Activating Factor and Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria—A Pilot Study in Adult Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Jan;23(17):9631.

- Piekarska K, Dratwa M, Radwan P, Radwan M, Bogunia-Kubik K, Nowak I. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization procedure treated with prednisone. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Sep 6 [cited 2024 Dec 7];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1250488/full. [CrossRef]

- Koch S, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006502.

- Kut C, Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Where is VEGF in the body? A meta-analysis of VEGF distribution in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007 Oct 8;97(7):978–85. [CrossRef]

- De Vita F, Orditura M, Lieto E, Infusino S, Morgillo F, Martinelli E, Castellano P, Romano C, Ciardiello F, Catalano G, Pignatelli C, Galizia G. Elevated perioperative serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels in patients with colon carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Jan 15;100(2):270–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Chen XT, Zhang H, Chen X. Expression analysis of cytokines IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17 and VEGF in breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2022 Dec 1;12:1019247.

- Balalis D, Tsakogiannis D, Kalogera E, Kokkali S, Tripodaki E, Ardavanis A, Manatakis D, Dimas D, Koufopoulos N, Fostira F, Korkolis D, Misitzis I, Vassos N, Spiliopoulou C, Vlachodimitropoulos D, Bletsa G, Arkadopoulos N. Serum Concentration of Selected Angiogenesis-Related Molecules Differs among Molecular Subtypes, Body Mass Index and Menopausal Status in Breast Cancer Patients. J Clin Med. 2022 Jul 14;11(14):4079. [CrossRef]

- Koukourakis MI, Limberis V, Tentes I, Kontomanolis E, Kortsaris A, Sivridis E, Giatromanolaki A. Serum VEGF levels and tissue activation of VEGFR2/KDR receptors in patients with breast and gynecologic cancer. Cytokine. 2011 Mar 1;53(3):370–5. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG J, YIN L, WU J, ZHANG Y, XU T, MA R, CAO H, TANG J. Detection of serum VEGF and MMP-9 levels by Luminex multiplexed assays in patients with breast infiltrative ductal carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2014 Jul;8(1):175–80. [CrossRef]

- Benoy I, Salgado R, Colpaert C, Weytjens R, Vermeulen PB, Dirix LY. Serum Interleukin 6, Plasma VEGF, Serum VEGF, and VEGF Platelet Load in Breast Cancer Patients. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2002 Jan 1;2(4):311–5. [CrossRef]

- Lu D peng, Zhou X yu, Yao L tian, Liu C gang, Ma W, Jin F, Wu Y fei. Serum soluble ST2 is associated with ER-positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014 Mar 18;14:198.

- Karayiannakis AJ, Syrigos KN, Zbar A, Baibas N, Polychronidis A, Simopoulos C, Karatzas G. Clinical significance of preoperative serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels in patients with colorectal cancer and the effect of tumor surgery. Surgery. 2002 May;131(5):548–55. [CrossRef]

- Broll R, Erdmann H, Duchrow M, Oevermann E, Schwandner O, Markert U, Bruch HP, Windhövel U. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) – a valuable serum tumour marker in patients with colorectal cancer? European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 2001 Feb 1;27(1):37–42.

- Kumar H, Heer K, Lee PW, Duthie GS, MacDonald AW, Greenman J, Kerin MJ, Monson JR. Preoperative serum vascular endothelial growth factor can predict stage in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998 May;4(5):1279–85.

- Crocker M, Ashley S, Giddings I, Petrik V, Hardcastle A, Aherne W, Pearson A, Anthony Bell B, Zacharoulis S, Papadopoulos MC. Serum angiogenic profile of patients with glioblastoma identifies distinct tumor subtypes and shows that TIMP-1 is a prognostic factor. Neuro-Oncology. 2011 Jan 1;13(1):99–108. [CrossRef]

- Chiorean R, Berindan - Neagoe I, Braicu C, Florian S, Daniel-Corneliu L, Crisan D, Cernea V. Quantitative expression of serum biomarkers involved in angiogenesis and inflammation, in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: Correlations with clinical data. Cancer biomarkers : section A of Disease markers. 2014 Jun 2;14:185–94.

- Reynés G, Vila V, Martín M, Parada A, Fleitas T, Reganon E, Martínez-Sales V. Circulating markers of angiogenesis, inflammation, and coagulation in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2011 Mar 1;102(1):35–41.

- Gomułka K, Liebhart J, Gładysz U, Mędrala W. VEGF serum concentration and irreversible bronchoconstriction in adult asthmatics. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019 Jun;28(6):759–63. [CrossRef]

- Makowska JS, Cieślak M, Jarzębska M, Lewandowska-Polak A, Kowalski ML. Angiopoietin-2 concentration in serum is associated with severe asthma phenotype. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016 Mar 1;12:8. [CrossRef]

- Mostmans Y, Maurer M, Richert B, Smith V, Melsens K, De Maertelaer V, Saidi I, Corazza F, Michel O. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: Evidence of systemic microcirculatory changes. Clin Transl Allergy. 2024 Jan 27;14(1):e12335. [CrossRef]

- Samochocki Z, Bogaczewicz J, Sysa-Jędrzejowska A, McCauliffe DP, Kontny E, Wozniacka A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and other cytokines in atopic dermatitis, and correlation with clinical features. International Journal of Dermatology. 2016;55(3):e141–6. [CrossRef]

- Pihan M, Keddie S, D’Sa S, Church AJ, Yong KL, Reilly MM, Lunn MP. Raised VEGF. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018 Aug 15;5(5):e486.

- Kierszniewska-Stepien D, Pietras T, Gorski P, Stepien H. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor level in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European Cytokine Network. 2006 Mar 1;17(1):75–9.

- Farid Hosseini R, Jabbari Azad F, Yousefzadeh H, Rafatpanah H, Hafizi S, Tehrani H, Khani M. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014 Aug 2;28:85.

- Kouchaki E, Shahreza BO, Faraji S, Nikoueinejad H, Sehat M. The Association between Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-related Factors with Severity of Multiple Sclerosis. Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2016 Jun 26;204–11.

- Ziora D, Jastrzębski D, Adamek M, Czuba Z, J. JK, Grzanka A, Kasperska-Zajac A. Circulating concentration of markers of angiogenic activity in patients with sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2015 Oct 5;15:113. [CrossRef]

- Öztop N, Özer PK, Demir S, Beyaz Ş, Tiryaki TO, Özkan G, Aydogan M, Bugra MZ, Çolakoglu B, Büyüköztürk S, Nalçacı M, Yavuz AS, Gelincik A. Impaired endothelial function irrespective of systemic inflammation or atherosclerosis in mastocytosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021 Jul;127(1):76–82. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi A, Asero R, Marzano AV, Lorini M, Fanoni D, Berti E, Cugno M. Plasma levels and skin-eosinophil-expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2009 Nov;64(11):1616–22. [CrossRef]

- Alkharsah, KR. VEGF Upregulation in Viral Infections and Its Possible Therapeutic Implications. IJMS. 2018 Jun 1;19(6):1642. [CrossRef]

- Tsai MJ, Wang TN, Lin YS, Kuo PL, Hsu YL, Huang MS. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists upregulate VEGF secretion from bronchial epithelial cells. J Mol Med. 2015 Nov;93(11):1257–69. [CrossRef]

- Bae O, Ahn S, Jin SH, Hong SH, Lee J, Kim ES, Jeong T, Chun Y, Lee AY, Noh M. Chemical allergens stimulate human epidermal keratinocytes to produce lymphangiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2015;283 2:147–55. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Kim MJ, Kumar A, Lee HW, Yang Y, Kim Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025 ;10(1):170. [CrossRef]

- Cusano NE, Rubin MR, Zhang C, Anderson L, Levy E, Costa AG, Irani D, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid Hormone 1–84 Alters Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Levels in Hypoparathyroidism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014 Oct 1;99(10):E2025–8. [CrossRef]

- Atalay, MA. Clinical significance of maternal serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level in idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;(Vol. 20-N. 14):2974–82.

- Nair PP, Shrivastava D. Evaluation of serum VEGF-A and interleukin 6 as predictors of angiogenesis during peri-implantation period assessed by Transvaginal Doppler Ultrasonography amongst women of prior reproductive failure: a cross-sectional analytical study. [Internet]. F1000Research; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 14]. Available from: https://f1000research. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Link H, Baluk P, Homer R, Chapoval S, Bhandari V, Kang MJ, Cohn L, Kim YK, McDonald D, Elias J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces remodeling and enhances TH2-mediated sensitization and inflammation in the lung. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:1095–103. [CrossRef]

- Chang WS, Do JH, Kim K, Kim YS, Lee SH, Yoon D, Kim EJ, Lee JK. The association of plasma cytokines including VEGF with recurrent wheezing in allergic patients. Asian Pacific journal of allergy and immunology [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 9]; Available from: https://consensus.app/papers/the-association-of-plasma-cytokines-including-vegf-with-chang-do/cdd53bbe4f275001834e4890b8705e91/.

- Yamashita T, Terada N, Hamano N, Kishi H, Kobayashi N, Kotani Y, Miura M, Konno A. Involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor in nasal obstruction in patients with nasal allergy. Allergology International. 2000;49(3):183–8. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, GL. Regulation of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis: a chaperone escorts VEGF to the dance. J Clin Invest. 2001 Jul 1;108(1):39–40.

- Ahluwalia A, Tarnawski AS. Critical role of hypoxia sensor--HIF-1α in VEGF gene activation. Implications for angiogenesis and tissue injury healing. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(1):90–7.

- Eisermann K, Fraizer G. The Androgen Receptor and VEGF: Mechanisms of Androgen-Regulated Angiogenesis in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2017 Apr 10;9(4):32. [CrossRef]

- Korbecki J, Simińska D, Gąssowska-Dobrowolska M, Listos J, Gutowska I, Chlubek D, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. Chronic and Cycling Hypoxia: Drivers of Cancer Chronic Inflammation through HIF-1 and NF-κB Activation: A Review of the Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 2;22(19):10701. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Liu Z, Li L, Jiang M, Tang Y, Zhou L, Li J, Chen Y. Sesamin inhibits hypoxia-stimulated angiogenesis via the NF-κB p65/HIF-1α/VEGFA signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer. Food Funct. 2022 Aug 30;13(17):8989–97. [CrossRef]

- Asano-Kato N, Fukagawa K, Okada N, Kawakita T, Takano Y, Doğru M, Tsubota K, Fujishima H. TGF-beta1, IL-1beta, and Th2 cytokines stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor production from conjunctival fibroblasts. Experimental eye research. 2005;80 4:555–60. [CrossRef]

- Lee KW, Park S, Kim SR, Min KH, Lee K, Choe Y, Hong SH, Lee YR, Kim JS, Hong S, Lee YC. Inhibition of VEGF blocks TGF-β1 production through a PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. European Respiratory Journal. 2008;31:523–31.

- Soares SR, Gómez R, Simón C, García-Velasco JA, Pellicer A. Targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor system to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(4):321–33.

- Wu WB, Chen HT, Lin JJ, Lai TH. VEGF Concentration in a Preovulatory Leading Follicle Relates to Ovarian Reserve and Oocyte Maturation during Ovarian Stimulation with GnRH Antagonist Protocol in In Vitro Fertilization Cycle. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021 Jan;10(21):5032. [CrossRef]

- Gómez R, Simón C, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Administration of moderate and high doses of gonadotropins to female rats increases ovarian vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor-2 expression that is associated to vascular hyperpermeability. Biol Reprod. 2003 Jun;68(6):2164–71. [CrossRef]

- Friedman CI, Seifer DB, Kennard EA, Arbogast L, Alak B, Danforth DR. Elevated level of follicular fluid vascular endothelial growth factor is a marker of diminished pregnancy potential. Fertil Steril. 1998 Nov;70(5):836–9. [CrossRef]

- Monteleone P, Giovanni Artini P, Simi G, Casarosa E, Cela V, Genazzani AR. Follicular fluid VEGF levels directly correlate with perifollicular blood flow in normoresponder patients undergoing IVF. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008 May;25(5):183–6. [CrossRef]

- Hannan NJ, Paiva P, Meehan KL, Rombauts LJF, Gardner DK, Salamonsen LA. Analysis of fertility-related soluble mediators in human uterine fluid identifies VEGF as a key regulator of embryo implantation. Endocrinology. 2011 Dec;152(12):4948–56. [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos B, Nikolettos N, Papachristou DN, Simopoulou M, Al-Hasani S, Diedrich K. Follicular fluid levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and leptin are associated with pregnancy outcome of normal women participating in intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. Physiol Res. 2005;54(3):263–70. [CrossRef]

- Lai TH, Vlahos N, Shih IM, Zhao Y. Expression Patterns of VEGF and Flk-1 in Human Endometrium during the Menstrual Cycle. J Reprod Infertil. 2015;16(1):3–9.

- Gomez Medellin JE, Hollinger MK, Rosenberg J, Blaine K, Kurtanich T, Ankenbruck N, Hrusch CL, Sperling AI, Swartz MA. VEGFR3-driven pulmonary lymphangiogenesis exacerbates induction of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue in allergic airway disease. The Journal of Immunology. 2022 May 1;208(Supplement_1):109.24-109.24. [CrossRef]

- Kunstfeld R, Hirakawa S, Hong YK, Schacht V, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Velasco P, Lin C, Fiebiger E, Wei X, Wu Y, Hicklin D, Bohlen P, Detmar M. Induction of cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions in VEGF-A transgenic mice results in chronic skin inflammation associated with persistent lymphatic hyperplasia. Blood. 2004 Aug 15;104(4):1048–57.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).