1. Introduction

Obesity has emerged as a global health crisis, contributing significantly to the rising burden of cancer worldwide. Beyond its well-known association with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, obesity is now recognized as a complex pathophysiological state that promotes tumorigenesis through both inflammatory and metabolic mechanisms [

1,

2]. The combination of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance in obese individuals prepares the ground for driving malignant evolution, tumor progression, and resistance to therapy.

Seminal studies have laid the groundwork for understanding how systemic inflammation contributes to cancer hallmarks such as sustained proliferation, resistance to cell death, angiogenesis, and metastasis [

3,

4]. The landmark article by Hanahan and Weinberg (2000) defined these hallmarks as central traits acquired during cancer development, and follow-up research has increasingly emphasized the pro-tumorigenic role of inflammation in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

5,

6].

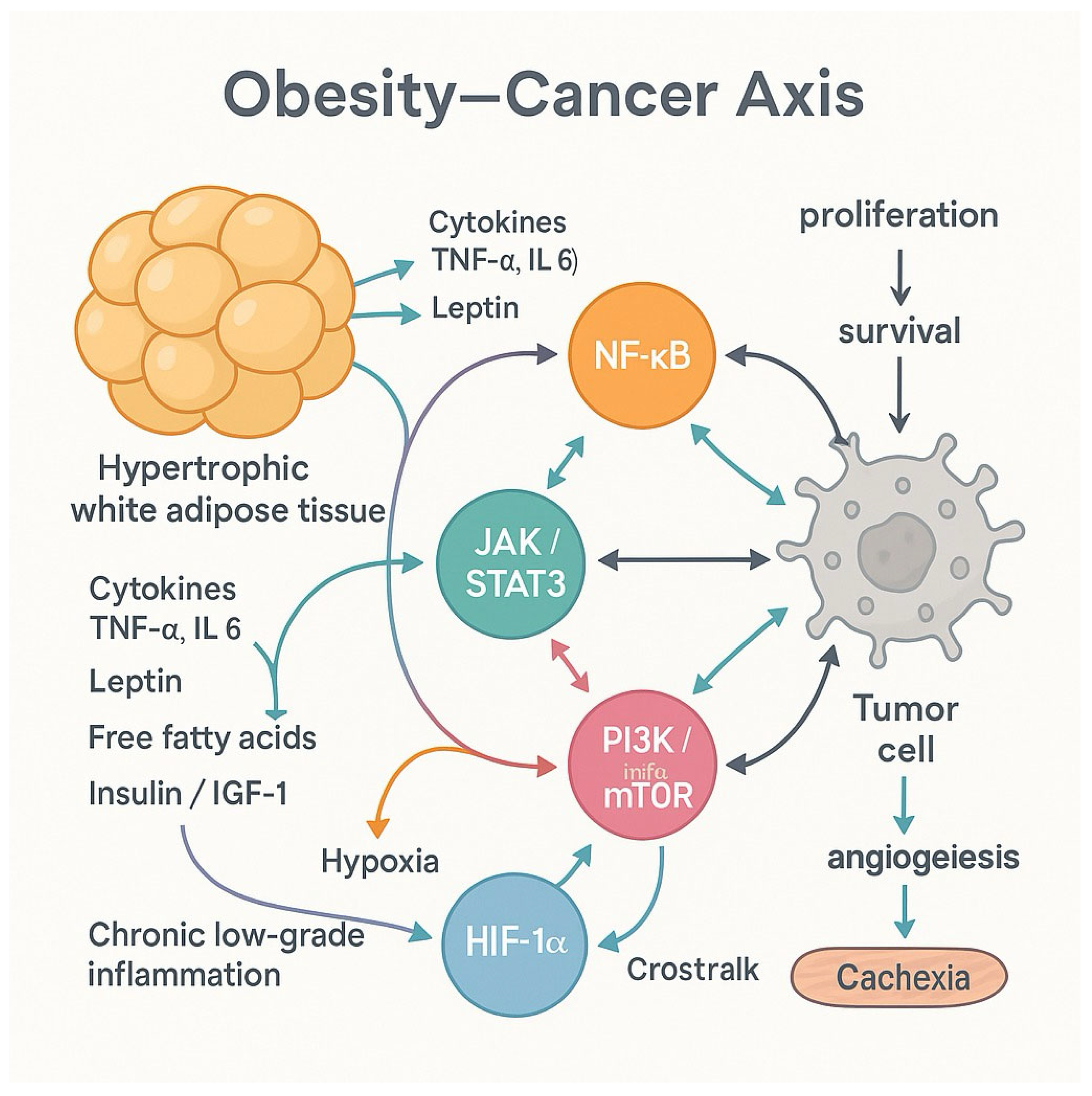

Obesity amplifies these inflammatory signals. Adipose tissue in obese individuals becomes a hub of immune activity, secreting cytokines and adipokines that trigger oncogenic signaling pathways. The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathways are key mediators linking adiposity to carcinogenesis, while metabolic disturbances such as hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia further exacerbate the risk [

2,

7,

8].

Large epidemiological cohorts and mechanistic studies have substantiated these insights. For example, a 2016 study published in the

New England Journal of Medicine confirmed that excess body weight is associated with elevated risks of at least 13 types of cancer, reinforcing obesity as a modifiable cancer risk factor [

9].

Recent advances also highlight the importance of immune and stromal remodeling in the TME of obese patients with cancer. Ringel et al. (2022) showed that obesity shapes the immune landscape of tumors, impairing anti-tumor immunity and promoting cancer cell escape mechanisms [

10].

This review synthesizes classic and contemporary literature to explore how obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance function as central drivers of cancer. It further discusses the molecular pathways involved, summarizes epidemiological trends and outlines therapeutic interventions that may help mitigate this growing public health challenge.

2. Cancer Risk in Obesity: Epidemiological Evidence

A compelling body of epidemiological research has established obesity as a major risk factor for a diverse array of cancers [

9]. This association is not merely correlative — it reflects the biological consequences of obesity-related inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, which promote tumorigenesis through both systemic and tissue-specific mechanisms [

1].

Studies have shown that higher body mass index (BMI) is significantly associated with increased incidence and poorer outcomes in cancers of the breast (postmenopausal), colorectal region, endometrium, pancreas, kidney, liver, and esophagus [

11]. Notably, the magnitude of cancer risk tends to rise with both the degree and duration of obesity, underscoring the cumulative effect of chronic metabolic and inflammatory stress [

12].

In women, obesity-related insulin resistance and hormonal imbalances—particularly involving estrogen and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs)—are central to the development of gynecological cancers, including breast, endometrial, and ovarian malignancies [

13]. Recent research has linked metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), a common obesity-related condition, to an elevated risk of breast cancer, particularly due to insulin resistance and lipid accumulation in hepatic tissues [

14]. Recent research has linked MASLD, a common obesity-related condition, to an elevated risk of breast cancer, particularly due to insulin resistance and lipid accumulation in hepatic tissues [

15,

60].

A study by Dhar and Bhattacharjee (2024) further highlighted the genetic landscape of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which is frequently comorbid with obesity. They identified insulin resistance and chronic low-grade inflammation as key drivers in the pathogenesis of endometrial and ovarian cancers, particularly in obese individuals [

16].

The link between obesity and cancer is also evident in male populations. Adiposity has been associated with higher rates of colorectal, liver, and renal cancers [

17,

18,

19], largely due to systemic inflammation and hormonal dysregulation affecting androgens and adipokines [

3].

Importantly, these epidemiological trends are supported by mechanistic studies demonstrating how obesity-related metabolic changes drive cellular transformation, DNA damage, and immune evasion [

1]. Together, these findings reinforce the importance of preventive strategies and early interventions in reducing obesity-associated cancer burden at the population level [

2].

3. Tumor-Associated Inflammation: Friend and Foe

Inflammation, traditionally considered a defensive biological response, plays a paradoxical role in the context of cancer. Instead of solely protecting the host, chronic low-grade inflammation—common in obesity—establishes a permissive environment for tumor development and progression. This duality is reflected in inflammatory mediators’ capacity to initiate oncogenic processes and support tumor survival and expansion [

20].

Table 1 summarizes the main Immune and stromal cells, cytokines/adipokines, and signaling pathways linking obesity-associated chronic inflammation with cancer progression.

Inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), are elevated in obese individuals and accumulate within the TME. These molecules activate transcription factors like NF-κB and STAT3, which regulate genes involved in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and inhibition of apoptosis [

1,

2,

20]. This signaling cascade supports early neoplastic transformations and sustains tumor growth by evading immune surveillance.

Moreover, chronic inflammation promotes the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM), facilitating both angiogenesis and metastatic invasion [

21]. Inflammatory cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and neutrophils contribute to this remodeling, producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and pro-angiogenic chemokines [

7,

22]. These changes ensure a steady blood supply to the tumor and promote its dissemination to distant tissues.

A crucial consequence of the inflammatory milieu is the induction of EMT —a cellular reprogramming event that endows cancer cells with migratory and invasive capabilities. TNF-α, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and other cytokines synergistically activate EMT through Snail, Twist, and ZEB transcription factors, transforming epithelial tumor cells into mesenchymal-like phenotypes that resist therapy and evade detection [

6,

23,

24].

Thus, in obesity-driven carcinogenesis, inflammation serves as a central enabler of tumor hallmarks, transforming the TME from a battlefield into a sanctuary for cancer cells.

4. Obesity as a Chronic Inflammatory State

Obesity is not merely a disorder of excess energy storage—it is increasingly recognized as a state of persistent, low-grade systemic inflammation. This condition arises from the pathological expansion and dysfunction of white adipose tissue (WAT), which transforms from a relatively inert depot into an active endocrine and immune organ that fuels carcinogenic processes [

9,

25,

26].

As adipose tissue enlarges, it becomes hypoxic and fibrotic, leading to the recruitment of immune cells, especially M2 macrophages polarization, T lymphocytes, and neutrophils, into the adipose milieu. Adopting a pro-inflammatory profile, these immune cells release cytokines — including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 — that fuel a self-sustaining inflammatory loop and drive systemic insulin resistance [

1,

2,

27,

28].

Adipocytes contribute to this inflammatory storm by altering their secretion of adipokines—bioactive peptides that regulate metabolism and immune function. In obesity, the balance of adipokines turns significantly: leptin levels rise, supporting pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic activities, while adiponectin levels fall, removing an important anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing brake [

2]. This dysregulation exacerbates metabolic disturbances and creates a microenvironment favorable to tumor growth.

Moreover, crosstalk between adipocytes and macrophages intensifies inflammation throughout paracrine signaling [

28]. Free fatty acids released by hypertrophic adipocytes activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on immune cells, further enhancing the release of inflammatory cytokines, promoting inflammation and subsequent cellular insulin resistance [

29]. This sustained inflammatory interaction primes distant tissues—such as the liver [

30,

31], colon [

32,

33], and breast [

34,

35]—for malignant transformation, linking obesity directly to increased cancer risk [

36,

37].

The systemic reach of this inflammatory state affects not only insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis but also immune surveillance, cell cycle regulation, and DNA repair—thereby functioning as a cancer-enabling mechanism at the metabolic-immunological interface [

38,

39].

5. Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Dysregulation

A key feature of obesity-driven metabolic abnormalities is insulin resistance, characterized by impaired cellular responsiveness to insulin’s regulatory actions on glucose and lipid metabolism. This chronic dysfunction impairs glycemic control and profoundly influences cancer progression, as well as the advancement through growth-promoting and anti-apoptotic pathways [

40,

41].

Insulin resistance in obese individuals often leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, whereby pancreatic β-cells increase insulin output to maintain blood glucose homeostasis [

41,

42]. This persistent elevation of insulin levels has oncogenic implications. Insulin directly stimulates mitogenic pathways such as PI3K/Akt and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK), which facilitate cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and survival in precancerous and malignant cells [

43]. In parallel, elevated insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) amplifies these signals by binding to its receptor (IGF-1R), which is overexpressed in several tumor types [

44,

45].

In addition to insulin and IGF-1, metabolic dysregulation encompasses hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, both of which contribute to cancer-promoting effects [

46]. High glucose levels create a pro-oxidant environment, enhancing DNA damage and supporting anaerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) — a hallmark of cancer metabolism [

4,

6]. Meanwhile, elevated triglycerides and free fatty acids provide fuel for rapidly dividing cancer cells and activate lipid-sensitive transcription factors, which modulate gene expression in favor of tumorigenesis [

47]. Saturated fatty acids, liberated through obesity-associated lipolysis, promote macrophage activation via engagement of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), leading to the stimulation of NF-κB signaling pathways. This activation subsequently drives the transcription of proinflammatory genes, such as COX-2, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα [

48].

Dysregulated metabolism also affects immune cell function, impairing anti-tumor immunity and reinforcing a chronic inflammatory state [

49]. Inflammatory adipokines, such as resistin and visfatin, further disrupt tissue insulin signaling, completing a feedback loop that links metabolic dysfunction with oncogenic transformation [

50].

Notably, this metabolic-inflammatory interface varies by sex, organ system, and hormonal context. For instance, in women, MASLD has been implicated in elevated risk for breast and gynecological cancers, partly due to altered estrogen metabolism and insulin resistance [

51].

6. Molecular Pathways Linking Obesity and Cancer

A network of intracellular signaling bridges the interface between chronic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in obesity cascades, collectively driving tumor initiation, promotion, and progression [

12]. These molecular pathways are activated in response to cytokines, free fatty acids, and hyperinsulinemia, and they regulate diverse processes such as cell survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, and immune modulation [

52].

Figure 1 describes the Intracellular signaling networks link chronic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in obesity, triggering pathways—stimulated by cytokines, free fatty acids, and hyperinsulinemia.

Among the central players is the NF-κB pathway. NF-κB is a transcription factor that responds to inflammatory stimuli like TNF-α and IL-6 and promotes the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, and angiogenesis. In obese individuals, NF-κB is constitutively activated due to chronic low-grade inflammation, thus maintaining a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [

1,

53].

Another critical signaling route is the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, particularly STAT3. Activated by IL-6 and leptin, STAT3 upregulates oncogenes such as Cyclin D1, Bcl-XL, and VEGF, supporting tumor growth and angiogenesis [

54]. Leptin, which is elevated in obesity, is especially potent in activating STAT3, linking adiposity to tumor promotion through leptin-STAT signaling [

54,

55].

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, primarily stimulated by insulin and IGF-1, integrates metabolic cues into cellular growth and survival. In many cancers, this pathway is hyperactivated due to either insulin resistance or receptor overexpression, contributing to uncontrolled proliferation and resistance to cell death [

56,

57].

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), stabilized under hypoxic conditions common in hypertrophic adipose tissue, further enhances angiogenesis and glycolysis—both necessary for tumor expansion. HIF-1α also cooperates with NF-κB and PI3K/Akt to modify the tumor stroma and promote immune evasion [

58,

59].

These pathways do not act in isolation. They converge and interact, reinforcing each other’s outputs and creating a self-sustaining oncogenic loop in obese individuals. Obesity creates a paradoxical biological environment in cancer. On

the one hand, its metabolic and inflammatory pathways converge and interact, reinforcing each other’s outputs and creating a self-sustaining oncogenic loop [

60]. This molecular synergy explains why obesity not only increases cancer incidence but also correlates with aggressive disease phenotypes and poorer prognoses. On the other hand, observational studies have reported an “obesity paradox,” where overweight or mildly obese cancer patients sometimes exhibit improved survival. This apparent contradiction is influenced by methodological limitations. First, reverse causality occurs when weight loss caused by undiagnosed cancer precedes diagnosis, potentially distorting the association between body weight and survival. Second, collider stratification bias arises when analyses condition on disease status (such as having cancer), which can introduce spurious associations between obesity and survival. Lastly, the use of BMI as a proxy for adiposity is inherently limited, as BMI does not distinguish between fat mass, lean muscle, and fat distribution—all of which may differentially influence cancer outcomes [

61,

62]. In obese patients, white adipose tissue may contribute to a chronic inflammatory microenvironment, thereby promoting tumor progression, as previously described. Conversely, in certain cancer types, the conversion of white adipose tissue into brown adipose tissue—a process known as “browning”—has been associated with weight loss. Although this phenomenon might be considered beneficial in the context of obesity, it has been linked to poorer prognosis in specific oncologic populations due to the accompanying metabolic alterations. These include the secretion of pro-inflammatory and catabolic mediators involved in cancer cachexia and body mass loss, such as Lipid Mobilizing Factor (LMF), Proteolysis Inducing Factor (PIF), and Parathyroid Hormone-related Protein (PTHrP).[

63,

64]

Furthermore, some tumors in obese individuals may exhibit less aggressive biology or better treatment responses, while excess adipose tissue might serve as an energy reserve during anticancer therapy, including malignancies characterized by elevated metabolic requirements and increased energy expenditure, such as head and neck cancers and esophageal carcinoma [

65,

66]. Previous data indicate that, in esophageal cancer, elevated BMI and increased visceral adiposity are associated with a higher risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. However, an inverse association has been observed between BMI, abdominal fat, and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Moreover, specific components of metabolic syndrome—such as diabetes mellitus—may confer a survival advantage in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, though this effect is not observed in adenocarcinoma [

67]. These findings suggest that the metabolic phenotype of adipose tissue may exhibit distinct biomarker profiles depending on the tumor’s histological subtype [

68]. Thus, obesity’s role in cancer is both deleterious and, under specific circumstances, deceptively protective—a paradox demanding cautious interpretation and methodological rigor.

7. Inflammation-Induced EMT, Angiogenesis, and Metastasis

The transition from localized tumor growth to metastatic dissemination is heavily influenced by chronic inflammation—particularly in the context of obesity. Inflammatory signals not only support tumor proliferation but also orchestrate the molecular events underlying EMT, angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling—all essential for cancer invasion and metastasis [

24,

69].

EMT is a process wherein epithelial cells lose their cell–cell adhesion and apical-basal polarity and acquire mesenchymal traits, including motility and invasiveness. Inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and TGF-β act as key EMT inducers in the tumor microenvironment [

3]. These molecules activate transcription factors such as Snail, Twist, and ZEB1, which downregulate epithelial markers (e.g., E-cadherin) and upregulate mesenchymal markers (e.g., vimentin, N-cadherin) [

24,

69]. In obesity, adipose-derived cytokines enhance these EMT signals, creating a systemic predisposition to tumor aggressiveness [

5,

70].

The angiogenic switch, a hallmark of cancer progression, is likewise driven by obesity-induced inflammation. VEGF, generated by adipocytes and tumor-associated macrophages, plays a central position in stimulating neovascularization, ensuring a sustained nutrient supply for expanding tumors [

7,

22]. The pro-inflammatory state also induces HIF-1α, which amplifies VEGF transcription and promotes endothelial proliferation even under normoxic conditions [

58,

59].

Additionally, the ECM—Usually a structural barrier to metastasis—is degraded by MMPs, particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9, which are upregulated in obese, inflamed tissues [

21]. This ECM remodeling facilitates tumor cell escape from the primary site and invasion into the surrounding stroma and vasculature [

2,

24].

These interconnected processes—EMT, angiogenesis, and ECM degradation—are not only enhanced in obesity but also correlate with poor cancer outcomes, including therapy resistance and early metastasis. Hence, targeting these inflammation-driven mechanisms is a promising therapeutic avenue for obesity-related malignancies [

2].

8. Interventions and Future Directions

Given the well-established links between obesity, chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and cancer, therapeutic strategies are increasingly focused on targeting the metabolic-inflammatory axis to reduce cancer risk and improve outcomes in obese patients. These interventions span lifestyle, pharmacological, and molecular domains, with promising implications for both prevention and therapy [

71,

72].

Diet and Nutrition

Modifiable risk factors play a key role in reducing the incidence and prevalence of both obesity and cancer. Current guidelines and studies emphasize that dietary improvements, reduced alcohol consumption, and regular physical activity are fundamental pillars of a healthy lifestyle and critical strategies for the prevention of obesity and non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) [

73,

74]. In addition to its role in cancer and obesity prevention, nutrition is essential during cancer treatment, as maintaining a healthy body weight has been associated with improved tolerance to antineoplastic therapies. Among cancer survivors, adherence to a healthy dietary pattern and the prevention of excessive weight gain have been linked to better long-term survival outcomes [

75].

The Mediterranean diet has shown promise in reversing obesity trends. It is characterized by the consumption of minimally processed and plant-based foods with high fiber content (vegetables, fruits, legumes), healthy fats that support cardiovascular health (nuts, olive oil), whole grains, and lean proteins—especially fish and seafood—as well as moderate intake of dairy (with emphasis on yogurt), and limited consumption of red meat and sweets. This dietary pattern has been associated with a reduced risk of several cancer types, including colorectal, gastric, head and neck, breast, and renal cell carcinoma. In contrast, the Western diet—rich in ultra-processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages—is more strongly associated with obesity and NCDs [

76,

77,

78].

Physical Activity

Physical activity plays an essential role in the management of obesity by promoting a reduction in body fat, particularly visceral or abdominal adiposity. This contributes to the improvement of the inflammatory profile through decreased estrogen levels and enhanced insulin sensitivity. Evidence indicates that regular physical exercise also serves as a preventive factor for cancer, with notable associations observed in breast, colorectal, endometrial, esophageal adenocarcinoma, gastric, renal, bladder, and lung cancers [

74].

These protective effects are primarily attributed to reductions in oxidative stress and DNA damage and suppression of inflammatory signaling pathways involved in the development of NCDs and carcinogenesis [

73,

79].

Current recommendations advocate for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity exercise. In cancer patients, physical activity has been associated with improved chemotherapy uptake by enhancing tissue perfusion and normalizing tumor microenvironment vasculature. Furthermore, it has been linked to increased overall survival and a reduced risk of developing a second primary tumor [

80,

81].

Anti-Inflammatory Agents

Chronic low-grade inflammation contributes significantly to the oncogenic potential of obesity, making anti-inflammatory approaches an attractive option. Agents such as aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and metformin have been shown to reduce the incidence of several cancers by inhibiting pro-inflammatory pathways like NF-κB and COX-2 and improving insulin sensitivity [

8,

72]. Additionally, vitamin D supplementation has demonstrated modulatory effects on inflammatory signaling and leptin-mediated carcinogenesis in obesity [

82].

Emerging Molecular Targets

As our understanding deepens, novel therapeutic targets are emerging. Inhibitors of STAT3, HIF-1α, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling are under investigation for their roles in disrupting obesity-driven tumor pathways. Immunometabolism, a field that studies the interface of immune signaling and metabolic function, is opening new avenues for cancer immunotherapy specifically tailored to obese patients [

2,

56].

Despite these advances, a major challenge remains in tailoring interventions to individual patients. Future research must address the heterogeneity in metabolic profiles, genetic predispositions, and cancer types, while also considering sex-specific hormonal environments and the role of gut microbiota [

88].

A multidisciplinary approach—integrating oncology, endocrinology, immunology, and nutrition—will be essential in crafting personalized strategies to mitigate the cancer risk imposed by obesity and metabolic disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Kamal S. Saini]; Methodology and Literature Review: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho, Kamal S. Saini]; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho, Kamal S. Saini]; Writing – Review and Editing: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho, Paulo Ricardo Santos Nunes Filho, Luca Cantin, Laura Vidal, Kamal S. Saini, Maria Carolina Santos Mendes, José Barreto Campello Carvalheira]; Visualization: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho, Luca Cantin, Kamal S. Saini]; Supervision: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho, Luca Cantin, Maria Carolina Santos Mendes, José Barreto Campello Carvalheira, Kamal S. Saini]; Project Administration: [Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior, Kamal S. Saini].

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT (version 4.5; OpenAI) to assist in the creation of one image, Grammarly® (Grammarly Inc.) for grammar and language refinement, and EndNote® (Clarivate) for reference management and citation formatting. The authors retained full responsibility for the content, interpretation, and conclusions of this manuscript. Additional thanks to the editorial team of journal Onco/MDPI. for providing a clear and structured review framework.

Conflicts of Interest

Larissa Ariel Oliveira Carrilho and Maria Carolina Santos Mendes have no conflict of interest. Ademar Dantas da Cunha Junior (ADCJ), Paulo Ricardo Santos Nunes Filho (PRSNF), Luca Cantin (LC) and Laura Vidal (LV) are a Fortrea employees and have company stock ownership. Kamal S. Saini (KSS) reports consulting fees from the European Commission, and stock and/or other ownership interests in Fortrea Inc. and Quantum Health Analytics (UK) Ltd, outside the submitted work. Jose Barreto Campello Carvalheira (JBCC) was funded by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) grants #2021/10265–8 and #2022/06239–4 (Cancer Theranostics Innovation Center (CancerThera)/CEPID—Centros de Pesquisa, Inovação e Difusão). Additionally, JBCC was supported by CNPq under process number 303429/2021–6. .

References

- Sagliocchi, S.; Acampora, L.; Barone, B.; Crocetto, F.; Dentice, M. The impact of the tumor microenvironment in the dual burden of obesity-cancer link. Semin Cancer Biol 2025, 112, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, A.; Sadida, H.Q.; Jerobin, J.; Elfaki, I.; Mir, R.; Mirza, S.; Singh, M.; Macha, M.A.; Uddin, S.; Fakhro, K.; et al. Unraveling molecular interconnections and identifying potential therapeutic targets of significance in obesity-cancer link. J Natl Cancer Cent 2025, 5, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, C.; Chen, K.; Gu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Li, Q. Investigating the causal association between obesity and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and underlying mechanisms. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha Junior, A.D.; Pericole, F.V.; Carvalheira, J.B.C. Metformin and blood cancers. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2018, 73, e412s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauby-Secretan, B.; Scoccianti, C.; Loomis, D.; Grosse, Y.; Bianchini, F.; Straif, K. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working, G. Body Fatness and Cancer-Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel, A.E.; Drijvers, J.M.; Baker, G.J.; Catozzi, A.; Garcia-Canaveras, J.C.; Gassaway, B.M.; Miller, B.C.; Juneja, V.R.; Nguyen, T.H.; Joshi, S.; et al. Obesity Shapes Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment to Suppress Anti-Tumor Immunity. Cell 2020, 183, 1848–1866 e1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Zhang, W. Obesity and cancer: inflammation bridges the two. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2016, 29, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.M.; Brown, K.A.; Iyengar, N.M. Targeting obesity-related dysfunction in hormonally driven cancers. Br J Cancer 2021, 125, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Si, C.; Gong, J.; Zhou, H.; Gu, J.; Qin, A.; Song, W.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cancer risk: A cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2025, 27, 1940–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, C.; Ganesan, K.; Ye, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Du, B.; Gao, F.; Song, C.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease promotes breast cancer progression through upregulated hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Bhattacharjee, P. Clinical-exome sequencing unveils the genetic landscape of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) focusing on lean and obese phenotypes: implications for cost-effective diagnosis and personalized treatment. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 24468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, P.O.; O’Reilly, D.A.; Renehan, A.G. Excess adiposity and gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Surg 2014, 101, 1518–1531; discussion 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.F.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Albanes, D.; Kipnis, V.; Moore, S.C.; Schatzkin, A.; Chow, W.H. Body size and renal cell cancer incidence in a large US cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2008, 168, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Pipia, I.; Ruiz, A.S.; Arguelles, I.; An, M.; Wase, S.; Peng, G. The molecular link between obesity and genomic instability in cancer development. Cancer Lett 2023, 555, 216035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Avila, G.; Sommer, B.; Mendoza-Posada, D.A.; Ramos, C.; Garcia-Hernandez, A.A.; Falfan-Valencia, R. Matrix metalloproteinases participation in the metastatic process and their diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2019, 137, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, P.; Grant, W.B. Vitamin D: What role in obesity-related cancer? Semin Cancer Biol 2025, 112, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitoh, M. Transcriptional regulation of EMT transcription factors in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2023, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, F.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Dong, Z.; Liu, K. Inflammation in cancer: therapeutic opportunities from new insights. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divella, R.; De Luca, R.; Abbate, I.; Naglieri, E.; Daniele, A. Obesity and cancer: the role of adipose tissue and adipo-cytokines-induced chronic inflammation. J Cancer 2016, 7, 2346–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.K. alpha-Tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol decrease inflammatory response and insulin resistance during the interaction of adipocytes and macrophages. Nutr Res Pract 2024, 18, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caslin, H.L.; Bhanot, M.; Bolus, W.R.; Hasty, A.H. Adipose tissue macrophages: Unique polarization and bioenergetics in obesity. Immunol Rev 2020, 295, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Favelyukis, S.; Nguyen, A.K.; Reichart, D.; Scott, P.A.; Jenn, A.; Liu-Bryan, R.; Glass, C.K.; Neels, J.G.; Olefsky, J.M. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 35279–35292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, A.; Rosso, C.; Bugianesi, E. Liver Cancer: Connections with Obesity, Fatty Liver, and Cirrhosis. Annu Rev Med 2016, 67, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, J.; Jaques, B.; Chattopadyhay, D.; Lochan, R.; Graham, J.; Das, D.; Aslam, T.; Patanwala, I.; Gaggar, S.; Cole, M.; et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol 2014, 60, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Shi, C.; Zou, Y.; Qin, H. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 86, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, K.; Chiodini, P.; Capuano, A.; Bellastella, G.; Maiorino, M.I.; Rafaniello, C.; Giugliano, D. Metabolic syndrome and postmenopausal breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause 2013, 20, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esper, R.M.; Dame, M.; McClintock, S.; Holt, P.R.; Dannenberg, A.J.; Wicha, M.S.; Brenner, D.E. Leptin and Adiponectin Modulate the Self-renewal of Normal Human Breast Epithelial Stem Cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015, 8, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Walker-Thurmond, K.; Thun, M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U. S. adults. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildir, G.; Akincilar, S.C.; Tergaonkar, V. Chronic adipose tissue inflammation: all immune cells on the stage. Trends Mol Med 2013, 19, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalamandris, S.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Papamikroulis, G.A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Papaioannou, S.; Deftereos, S.; Tousoulis, D. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetes: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Eur Cardiol 2019, 14, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, A.L.; Munger, C.J.; Ringel, A.E. Emerging insights into the impact of systemic metabolic changes on tumor-immune interactions. Cell Rep 2025, 44, 115234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, B.; Iiritano, S.; Nocera, A.; Possidente, K.; Nevolo, M.T.; Ventura, V.; Foti, D.; Chiefari, E.; Brunetti, A. Insulin resistance and cancer risk: an overview of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Exp Diabetes Res 2012, 2012, 789174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.V.; Kolka, C.M.; Kim, S.P.; Bergman, R.N. Obesity, insulin resistance and comorbidities? Mechanisms of association. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2014, 58, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, E.J.; LeRoith, D. The proliferating role of insulin and insulin-like growth factors in cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010, 21, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, D.; Yee, D. Disrupting insulin-like growth factor signaling as a potential cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2007, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Pourpak, A.; Morris, S.W. Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) tyrosine kinase as a novel cancer therapy approach. J Med Chem 2009, 52, 4981–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.W.; Rossi, E.L.; O’Flanagan, C.H.; deGraffenried, L.A.; Hursting, S.D. The Role of the Insulin/IGF System in Cancer: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials and the Energy Balance-Cancer Link. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koundouros, N.; Poulogiannis, G. Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer 2020, 122, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.R.; Subbaramaiah, K.; Hudis, C.A.; Dannenberg, A.J. Molecular pathways: adipose inflammation as a mediator of obesity-associated cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 6074–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, L.; Bonetti, L.; Brenner, D. Metabolic Modulation of Immunity: A New Concept in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell Rep 2020, 32, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nguyen, M.H. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A sexually dimorphic disease and breast and gynecological cancer. Metabolism 2025, 167, 156190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanti, J.F.; Ceppo, F.; Jager, J.; Berthou, F. Implication of inflammatory signaling pathways in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012, 3, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shen, S.; Verma, I.M. NF-kappaB, an active player in human cancers. Cancer Immunol Res 2014, 2, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Leptin-Induced JAK/STAT Signaling and Cancer Growth. Vaccines (Basel) 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, W.; Barczuk, J.; Racinska, O.; Siwecka, N.; Rozpedek-Kaminska, W.; Slupianek, A.; Sierpinski, R.; Majsterek, I. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Blood Malignancies-New Therapeutic Possibilities. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Junior, A.D.; Zanette, D.L.; Pericole, F.V.; Olalla Saad, S.T.; Barreto Campello Carvalheira, J. Obesity as a Possible Risk Factor for Progression from Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance Progression into Multiple Myeloma: Could Myeloma Be Prevented with Metformin Treatment? Adv Hematol 2021, 2021, 6615684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, V.; Santarsiero, A.; Convertini, P.; Todisco, S.; Iacobazzi, V. Cancer Cell Metabolism in Hypoxia: Role of HIF-1 as Key Regulator and Therapeutic Target. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Han, F.; Du, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W. Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Morley, T.S.; Kim, M.; Clegg, D.J.; Scherer, P.E. Obesity and cancer-mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon, H.; Sperrin, M.; Badrick, E.; Renehan, A.G. The Obesity Paradox in Cancer: a Review. Curr Oncol Rep 2016, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Giovannucci, E.L. The Obesity Paradox in Cancer: Epidemiologic Insights and Perspectives. Curr Nutr Rep 2019, 8, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Feng, X.; Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Chen, K.; Ye, Y. Fat Wasting Is Damaging: Role of Adipose Tissue in Cancer-Associated Cachexia. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, E.; Makowski, L.; DiGiovanni, J.; Kolonin, M.G. Cancer as a Matter of Fat: The Crosstalk between Adipose Tissue and Tumors. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Schellerer, V.S.; Brunner, M.; Geppert, C.I.; Grutzmann, R.; Weber, K.; Merkel, S. The impact of body mass index on prognosis in patients with colon carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis 2022, 37, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, L.A.O.; Juliani, F.L.; Moreira, R.C.L.; Dias Guerra, L.; Santos, F.S.; Padilha, D.M.H.; Branbilla, S.R.; Horita, V.N.; Novaes, D.M.L.; Antunes-Correa, L.M.; et al. Adipose tissue characteristics as a new prognosis marker of patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Front Nutr 2025, 12, 1472634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Cheng, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, P.; Cheng, Y. The prognostic significance of metabolic syndrome and weight loss in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabiatti, C.T.B.; Martins, M.C.L.; Miyazaki, D.L.; Silva, L.P.; Lascala, F.; Macedo, L.T.; Mendes, M.C.S.; Carvalheira, J.B.C. Myosteatosis in a systemic inflammation-dependent manner predicts favorable survival outcomes in locally advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Med 2019, 8, 6967–6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mansoori, L.; Al-Jaber, H.; Prince, M.S.; Elrayess, M.A. Role of Inflammatory Cytokines, Growth Factors and Adipokines in Adipogenesis and Insulin Resistance. Inflammation 2022, 45, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suren Garg, S.; Kushwaha, K.; Dubey, R.; Gupta, J. Association between obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance: Insights into signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2023, 200, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuttica, C.M.; Briata, I.M.; DeCensi, A. Novel Treatments for Obesity: Implications for Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research, F.; American Institute for Cancer, R. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective: a summary of the Third Expert Report; World Cancer Research Fund International: London, 2018; pp. 112 pages: illustrations (black and white, and colour). [Google Scholar]

- Isaksen, I.M.; Dankel, S.N. Ultra-processed food consumption and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2023, 42, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Di Bella, G.; Cusumano, C.; Parisi, A.; Tagliaferri, F.; Ciriminna, S.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Exp Gerontol 2023, 174, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczyrek, M.; Bitkowska, P.; Chunowski, P.; Czuchryta, P.; Krawczyk, P.; Milanowski, J. Diet, Microbiome, and Cancer Immunotherapy-A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, E.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Triggi, M.; Siargkas, A.; Chourdakis, M.; Haidich, A.B. Diet and Risk of Gastric Cancer: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Ryder-Burbidge, C.; McNeil, J. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behavior in cancer etiology: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Oncol 2021, 15, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.; Gansler, T.; Gapstur, S.M.; McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Andrews, K.S.; Bandera, E.V.; Spees, C.K.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin 2020, 70, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.V.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Moore, S.C.; Hayes, S.C.; Silver, J.K.; Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.; Gerber, L.H.; George, S.M.; Fulton, J.E.; et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019, 51, 2391–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Witkowska-Sedek, E.; Ruminska, M.; Stelmaszczyk-Emmel, A.; Sobol, M.; Majcher, A.; Pyrzak, B. Vitamin D Effects on Selected Anti-Inflammatory and Pro-Inflammatory Markers of Obesity-Related Chronic Inflammation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 920340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olukorode, J.O.; Orimoloye, D.A.; Nwachukwu, N.O.; Onwuzo, C.N.; Oloyede, P.O.; Fayemi, T.; Odunaike, O.S.; Ayobami-Ojo, P.S.; Divine, N.; Alo, D.J.; et al. Recent Advances and Therapeutic Benefits of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Agonists in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16, e72080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartikasari, A.E.R.; Huertas, C.S.; Mitchell, A.; Plebanski, M. Tumor-Induced Inflammatory Cytokines and the Emerging Diagnostic Devices for Cancer Detection and Prognosis. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 692142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Agarwal, M.; Aggarwal, M.; Alexander, L.; Apovian, C.M.; Bindlish, S.; Bonnet, J.; Butsch, W.S.; Christensen, S.; Gianos, E.; et al. Nutritional priorities to support GLP-1 therapy for obesity: a joint Advisory from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, the American Society for Nutrition, the Obesity Medicine Association, and The Obesity Society. Am J Clin Nutr 2025. [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, M.M.; Isaacs, M.; Bliuc, D.; Baldock, P.A.; Eisman, J.A.; White, C.P.; Greenfield, J.R.; Center, J.R. Effects of bariatric surgery and dietary intervention on insulin resistance and appetite hormones over a 3-year period. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar, L.O.; Goldberg, N.; Netz, U.; Berenstain, I.F.; Abu Zeid, E.E.D.; Avital, I.; Perry, Z.H. Association between metabolic and bariatric surgery and malignancy: a systematic review, meta-analysis, trends, and conclusions. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2025, 21, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofk, H.; Metallo, C.; Liu, G.; Rabinowitz, J.; Sparks, L.; James, D. Metabolic heterogeneity in humans. Cell 2024, 187, 3821–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).