Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

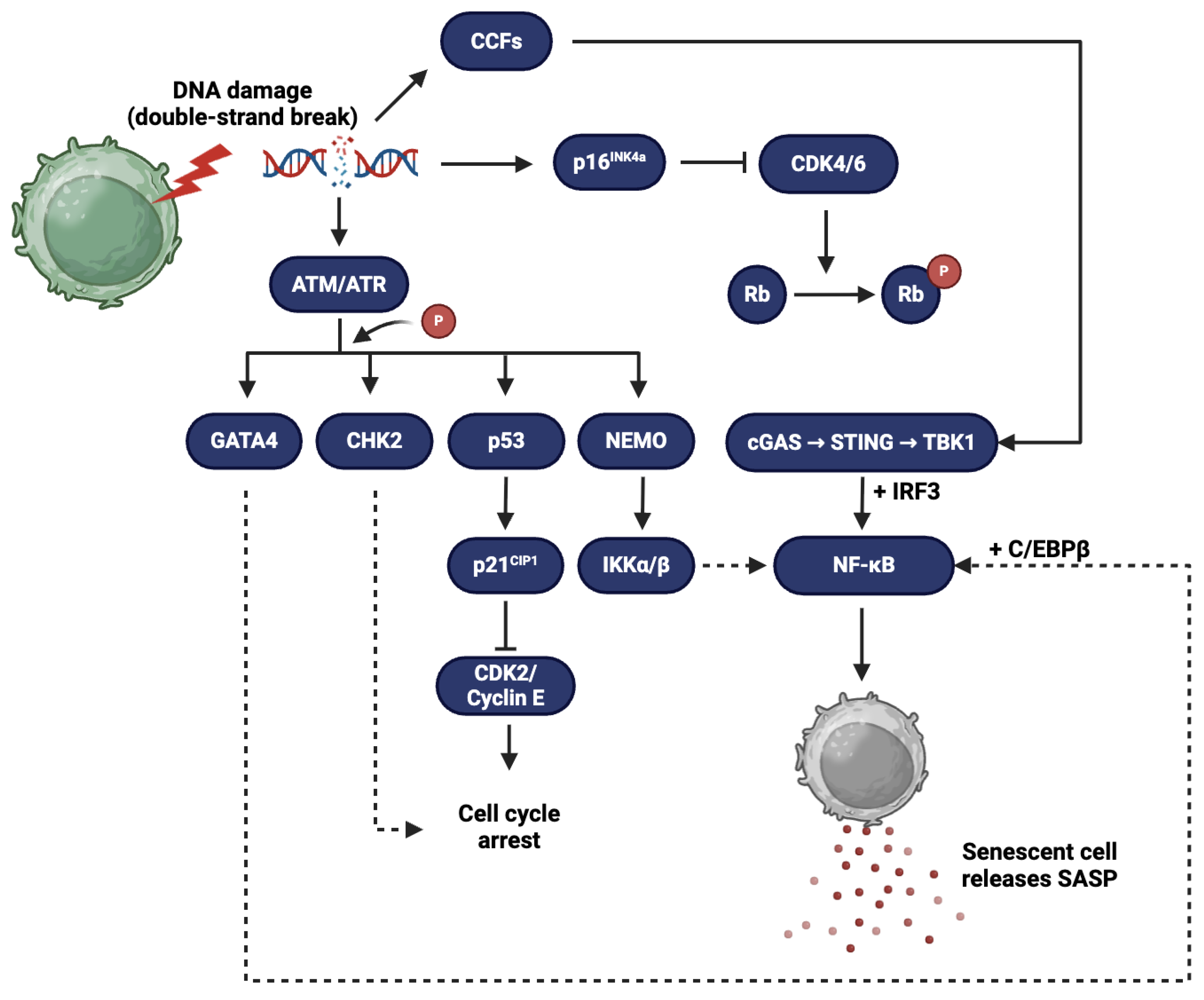

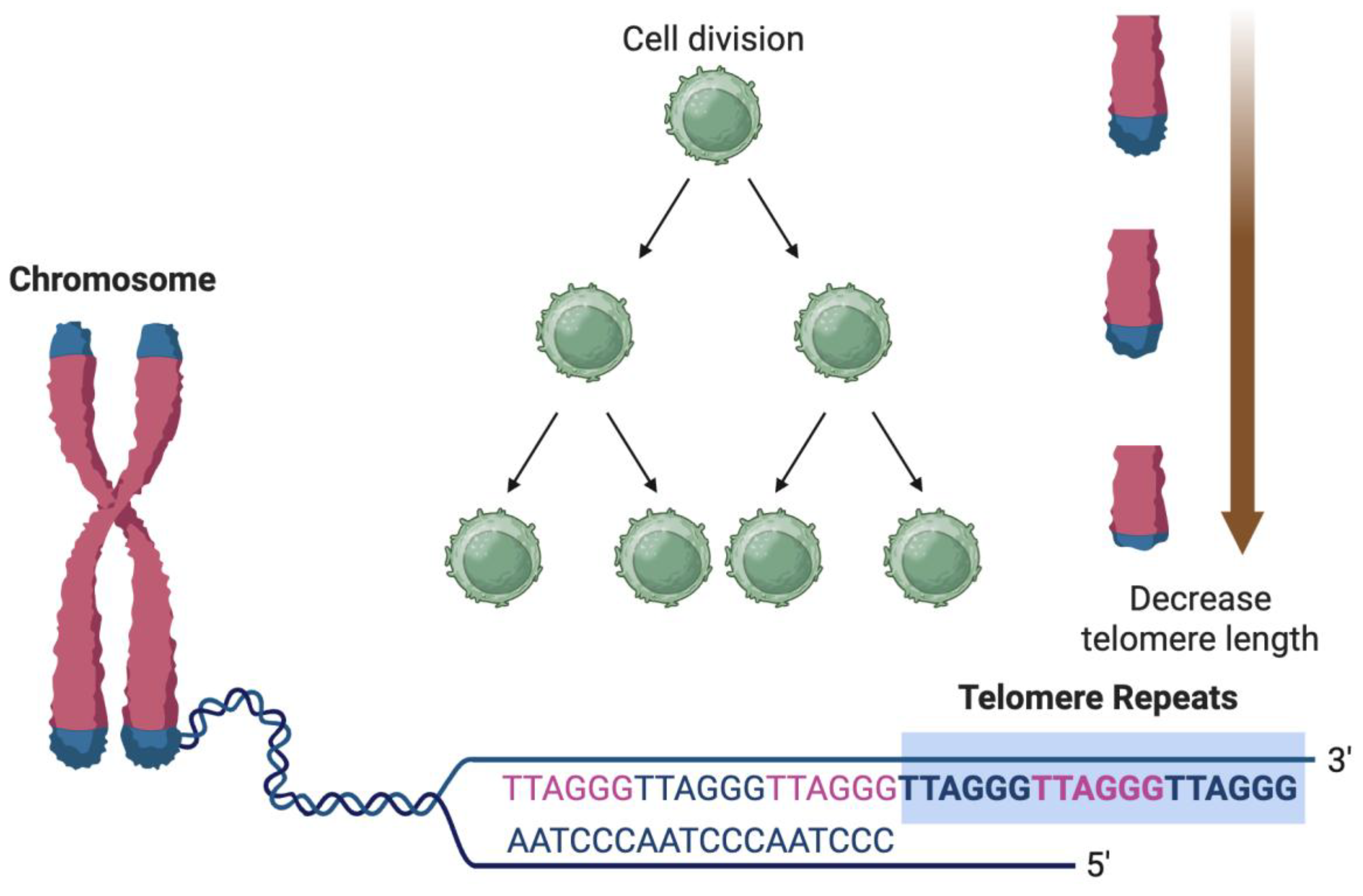

Cellular Senescence and SASP: Definitions and Mechanisms

Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence

Composition and Regulation of SASP

Triggers and Amplifiers of SASP

Distinction Between Transient vs Chronic SASP

SASP-Induced Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation ("Inflammaging")

SASP, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Vascular Aging

Effects of SASP on Vascular Endothelial Cells

Role of SASP in Arterial Stiffness

SASP and Atherosclerotic Heart Disease

Contribution of Senescent Cells and SASP in Atherogenesis

SASP and Plaque Instability

Evidence from Animal Models and Human Studies

SASP, Myocardial Remodeling, and Heart Failure

Senescence in Cardiomyocytes and Fibroblasts

SASP-Driven Fibrosis, Hypertrophy, and Impaired Contractility

Relevance in HFpEF in Elderly

SASP and Cardiac Arrhythmias

Biomarkers and Diagnostic Potential

Potential Biomarkers for SASP and Senescent Cell Burden

Use in Risk Stratification and Monitoring Therapy in Elderly CVD Patients

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting SASP

Senolytics and Their CV Impact

Senomorphics and Their CV Impact

Limitations of Currently Available Senolytics and Senomorphics

Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

Heterogeneity of Senescent Cells Across Tissues

Need for Longitudinal Human Studies

Interaction of SASP with Other Aging Hallmarks in CVD

Conclusion

Acknowledgement: None.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Rodgers, J.L.; Jones, J.; Bolleddu, S.I.; Vanthenapalli, S.; Rodgers, L.E.; Shah, K.; Karia, K.; Panguluri, S.K. Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, D.J.; Goldstein, D.R. Ageing and Atherosclerosis: Vascular Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors and Potential Role of IL-6. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021, 18, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Mecocci, P. The Importance of Cellular Senescence in Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases. In Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases. In Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases; Veronese, N., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-33329-4. [Google Scholar]

- Triposkiadis, F.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Butler, J. Cardiovascular Aging and Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2019, 74, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Procopio, A.D.; Rippo, M.R. Cellular Senescence and Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) in Aging Process. In Human Aging; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 75–88 ISBN 978-0-12-822569-1.

- Birch, J.; Gil, J. Senescence and the SASP: Many Therapeutic Avenues. Genes Dev 2020, 34, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBrasseur, N.K.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Cellular Senescence and the Biology of Aging, Disease, and Frailty. In Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series; Fielding, R.A., Sieber, C., Vellas, B., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2015; Vol. 83, pp. 11–18 ISBN 978-3-318-05477-4.

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Senescence in Wound Repair: Emerging Strategies to Target Chronic Healing Wounds. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Paul, K.H.; Minamino, T.; Miller, J.D.; Lerman, A.; Ellison-Hughes, G.M.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Senescent Cells: A Therapeutic Target in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Teng, T.; Ma, Z.-G.; Tang, Q.-Z. Cellular Senescence in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Aging Dis 2022, 13, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Jat, P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Armstrong, J.L.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Cellular Senescence and the Senescent Secretory Phenotype in Age-Related Chronic Diseases. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 2014, 17, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olan, I.; Handa, T.; Narita, M. Beyond SAHF: An Integrative View of Chromatin Compartmentalization during Senescence. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2023, 83, 102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N.; Arnold, R.; Equey, A.; Gandhi, A.; Adams, P.D. The Role of the Dynamic Epigenetic Landscape in Senescence: Orchestrating SASP Expression. NPJ Aging 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Living on a Break: Cellular Senescence as a DNA-Damage Response. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Purman, C.; Porter, S.I.; Nganga, V.; Saini, A.; Hayer, K.E.; Gurewitz, G.L.; Sleckman, B.P.; Bednarski, J.J.; Bassing, C.H.; et al. DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induce H2Ax Phosphorylation Domains in a Contact-Dependent Manner. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, S.; Kashyap, S.; Chini, E.; von Zglinicki, T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cell Senescence and Aging. J Clin Invest 2022, 132, e158447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, H.; Passos, J.F. Cellular Senescence: All Roads Lead to Mitochondria. The FEBS Journal 2023, 290, 1186–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavinson, V.; Linkova, N.; Dyatlova, A.; Kantemirova, R.; Kozlov, K. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype of Cardiovascular System Cells and Inflammaging: Perspectives of Peptide Regulation. Cells 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Pei, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ren, K. Cardiac Cell Senescence: Molecular Mechanisms, Key Proteins and Therapeutic Targets. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Kotla, S.; Reddy Velatooru, L.; Abe, R.J.; Davis, E.A.; Cooke, J.P.; Schadler, K.; Deswal, A.; Herrmann, J.; Lin, S.H.; et al. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype as a Hinge Between Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Chikenji, T.S. Role of Cellular Senescence in Inflammation and Regeneration. Inflammation and Regeneration 2024, 44, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, S.M. Interleukin-1α: Novel Functions in Cell Senescence and Antiviral Response. Cytokine 2022, 154, 155875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rane, M. Interleukin-6 Signaling and Anti-Interleukin-6 Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research 2021, 128, 1728–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and Age-Related Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Nie, L.; Zhao, P.; Ji, N.; Liao, G.; Wang, Q. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype and Its Impact on Oral Immune Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, J.K.; Danga, A.K.; Kumari, A.; Bhardwaj, A.; Rath, P.C. Role of Chemokines in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2025, 223, 112009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Rodríguez, S.; Folgueras, A.R.; López-Otín, C. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Aging: Tissue Remodeling and Beyond. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhu, X.; Pan, X. The Multifaceted Role of the SASP in Atherosclerosis: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Biosci 2022, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype and Its Physiological and Pathological Implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeki, T.; Tamura, Y.; Shinohara, H.; Tanaka, H.; Bando, K.; Fukuda, N. Role of Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Hepatocyte Growth Factor in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Heart Vessels 2000, 15, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.-L.; Miao, H.; Wang, Y.-N.; Liu, F.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.-Y. TGF-β as A Master Regulator of Aging-Associated Tissue Fibrosis. Aging Dis 2023, 14, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R. Chromatin Basis of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype. Trends Cell Biol 2022, 32, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salotti, J.; Johnson, P.F. Regulation of Senescence and the SASP by the Transcription Factor C/EBPβ. Exp Gerontol 2019, 128, 110752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroud, J.; Bouriez, I.; Paulus, H.; Pourtier, A.; Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Pluquet, O. Exploring the Communication of the SASP: Dynamic, Interactive, and Adaptive Effects on the Microenvironment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 10788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; He, X. Telomeres and Mitochondrial Metabolism: Implications for Cellular Senescence and Age-Related Diseases. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2022, 18, 2315–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.; Pothof, J.; Vijg, J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. The Central Role of DNA Damage in the Ageing Process. Nature 2021, 592, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreeya, T.; Ansari, M.S.; Kumar, P.; Saifi, M.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I. Senescence: A DNA Damage Response and Its Role in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging 2023, 4, 1292053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorelli, S.; Passos, J.F. Telomeres and Cell Senescence - Size Matters Not. eBioMedicine 2017, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiello, F.; Jurk, D.; Passos, J.F.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Telomere Dysfunction in Ageing and Age-Related Diseases. Nat Cell Biol 2022, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.-F.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Ungvari, Z. Mitochondria and Cardiovascular Aging. Circ Res 2012, 110, 10.1161–CIRCRESAHA.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayo, A.; Segovia, R.; Venturini, W.; Moore-Carrasco, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Brown, N. mTOR Activity and Autophagy in Senescent Cells, a Complex Partnership. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C.R.R.; Maurmann, R.M.; Guma, F.T.C.R.; Bauer, M.E.; Barbé-Tuana, F.M. cGAS-STING Pathway as a Potential Trigger of Immunosenescence and Inflammaging. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1132653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapaul, R.J.R.S.; Shvedova, M.; Shin, G.H.; Roh, D.S. An Insight into Aging, Senescence, and Their Impacts on Wound Healing. Adv Geriatr Med Res 2021, 3, e210017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Prattichizzo, F.; Grillari, J.; Balistreri, C.R. Cellular Senescence and Inflammaging in Age-Related Diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2018, 2018, 9076485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, N. The Roles and Mechanisms of Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP): Can It Be Controlled by Senolysis? Inflammation and Regeneration 2022, 42, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picos, A.; Seoane, N.; Campos-Toimil, M.; Viña, D. Vascular Senescence and Aging: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Prospects. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcena, M.L.; Aslam, M.; Pozdniakova, S.; Norman, K.; Ladilov, Y. Cardiovascular Inflammaging: Mechanisms and Translational Aspects. Cells 2022, 11, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-M.; Huang, A.; Kaley, G.; Sun, D. eNOS Uncoupling and Endothelial Dysfunction in Aged Vessels. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2009, 297, H1829–H1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellasamy, D.M.; Lee, S.-J.; Goh, K.W.; Goh, B.-H.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Ming, L.C.; Yap, W.H. Targeting Immune Senescence in Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, A.Á.; Pásztor, D.T.; Tarcza, Z.; Merkely, B. Cells in Atherosclerosis: Focus on Cellular Senescence from Basic Science to Clinical Practice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 17129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, T.; Lin, Y.-N.; Ibrahim, A. Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, J.F.; Ramírez, C.M.; Mittelbrunn, M. Inflammageing, a Targetable Pathway for Preventing Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiovascular Research 2024, cvae240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, S.; Iba, T.; Naito, H.; Rahmawati, F.N.; Konishi, H.; Jia, W.; Muramatsu, F.; Takakura, N. Aging Impairs the Ability of Vascular Endothelial Stem Cells to Generate Endothelial Cells in Mice. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrivou, D.; Perlepe, G.; Kirgou, P.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Malli, F. Pathophysiological Aspects of Aging in Venous Thromboembolism: An Update. Medicina 2022, 58, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.E.; Rai, R.; Khan, S.S.; Eren, M.; Ghosh, A.K. PAI-1 Is a Marker and a Mediator of Senescence. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Kim, S.Y. Endothelial Senescence in Vascular Diseases: Current Understanding and Future Opportunities in Senotherapeutics. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Navarro, I.; Botana, L.; Diez-Mata, J.; Tesoro, L.; Jimenez-Guirado, B.; Gonzalez-Cucharero, C.; Alcharani, N.; Zamorano, J.L.; Saura, M.; Zaragoza, C. Replicative Endothelial Cell Senescence May Lead to Endothelial Dysfunction by Increasing the BH2/BH4 Ratio Induced by Oxidative Stress, Reducing BH4 Availability, and Decreasing the Expression of eNOS. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kauppinen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Emerging Role of NF-κB Signaling in the Induction of Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). Cellular Signalling 2012, 24, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułdo, J.M.; Westra, J.; Ásgeirsdóttir, S.A.; Kok, R.J.; Oosterhuis, K.; Rots, M.G.; Schouten, J.P.; Limburg, P.C.; Molema, G. Differential Effects of NF-κB and P38 MAPK Inhibitors and Combinations Thereof on TNF-α- and IL-1β-Induced Proinflammatory Status of Endothelial Cells in Vitro. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2005, 289, C1229–C1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-W.; West, X.Z.; Byzova, T.V. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Angiogenesis and Vascular Disease. J Mol Med 2013, 91, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hadri, K.; Smith, R.; Duplus, E.; El Amri, C. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Senescence in Atherosclerosis: Thioredoxine-1 as an Emerging Therapeutic Target. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Vascular Aging in Hypertension. Hypertension 2017, 70, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Silva, J.C.; Nolasco, P.; Krieger, J.E.; Miyakawa, A.A. Dynamic Crosstalk between Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and the Aged Extracellular Matrix. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kračun, D.; Dustin, C.M.; El Massry, M.; Yuan, S.; Goossen, C.J.; DeVallance, E.R.; Sahoo, S.; St Hilaire, C.; Gurkar, A.U.; et al. Forestalling Age-Impaired Angiogenesis and Blood Flow by Targeting NOX: Interplay of NOX1, IL-6, and SASP in Propagating Cell Senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2015666118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dookun, E.; Walaszczyk, A.; Redgrave, R.; Palmowski, P.; Tual-Chalot, S.; Suwana, A.; Chapman, J.; Jirkovsky, E.; Donastorg Sosa, L.; Gill, E.; et al. Clearance of Senescent Cells during Cardiac Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury Improves Recovery. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacolley, P.; Regnault, V.; Segers, P.; Laurent, S. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Arterial Stiffening: Relevance in Development, Aging, and Disease. Physiological Reviews 2017, 97, 1555–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Z.S.; Rossman, M.J.; Mahoney, S.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Maurer, G.S.; Hutton, D.A.; VanDongen, N.S.; Greenberg, N.T.; Longtine, A.G.; Ludwig, K.R.; et al. Cellular Senescence Contributes to Large Elastic Artery Stiffening and Endothelial Dysfunction With Aging: Amelioration With Senolytic Treatment. Hypertension 2023, 80, 2072–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z. Aging, Arterial Stiffness, and Hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin; Wallace, S. ; McEniery, C.M.; Dakham, Z.; Pusalkar, P.; Maki-Petaja, K.; Ashby, M.J.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Wilkinson, I.B. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), MMP-2, and Serum Elastase Activity Are Associated With Systolic Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2005, 25, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutzmann, J.; Daniel, J.-M.; Bauersachs, J.; Hilfiker-Kleiner, D.; Sedding, D.G. Emerging Translational Approaches to Target STAT3 Signalling and Its Impact on Vascular Disease. Cardiovascular Research 2015, 106, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuday, E.; Islam, T.; Kim, J.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A.J. Abstract 13452: Age-Related Increases in Arterial Stiffness Is Attenuated With Long-Term Senolytic Therapy in Mice. Circulation 2022, 146, A13452–A13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, S.; Hutton, D.; Rossman, M.; Brunt, V.; VanDongen, N.; Casso, A.; Greenberg, N.; Ziemba, B.; Melov, S.; Campisi, J.; et al. Late-Life Treatment with the Senolytic ABT-263 Reverses Aortic Stiffening and Improves Endothelial Function with Aging. The FASEB Journal 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Liu, H.; Tu, Z. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Mediating Senescence of Vascular Endothelial Cells in Atherosclerosis. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology 2023, 37, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Beber, L.C.; Guma, F.T.C.R. The Macrophage Senescence Hypothesis: The Role of Poor Heat Shock Response in Pulmonary Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction Following Chronic Exposure to Air Pollution. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Susaki, E.A.; Nagaoka, I. Lipopolysaccharides and Cellular Senescence: Involvement in Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 11148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.R.; Koster, K.M.; Murphy, P.S. Efferocytosis Signaling in the Regulation of Macrophage Inflammatory Responses. The Journal of Immunology 2017, 198, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkar, S.S.; Leeper, N.J. Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2024, 21, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Xiang, L.; Xiao, L. Quercetin Alleviates Atherosclerosis by Suppressing Oxidized LDL-Induced Senescence in Plaque Macrophage via Inhibiting the p38MAPK/P16 Pathway. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2023, 116, 109314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-M.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.-W. The Emerging Role of Cell Senescence in Atherosclerosis. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 2021, 59, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Agostini, M.; Bernassola, F.; Bove, P.; Candi, E.; Rovella, V.; Sica, G.; et al. Macrophage Polarization and Metabolism in Atherosclerosis. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijckers, R.P.M.; Foks, A.C. Adaptive Immunity and Atherosclerosis: Aging at Its Crossroads. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Xuan, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Jin, H.; Dong, H. How Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype Switching Contributes to Vascular Disease. Cell Commun Signal 2022, 20, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.-Y.; Chen, A.-Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.-F.; Kong, X.-Q.; Zhang, J.-J. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Phenotypic Switching in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uryga, A.K.; Bennett, M.R. Ageing Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Senescence in Atherosclerosis. The Journal of Physiology 2016, 594, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, M.O.J.; Moulis, M.; Roth, L.; Martinet, W.; Vindis, C.; Bennett, M.R.; De Meyer, G.R.Y. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Death, Autophagy and Senescence in Atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular Research 2018, 114, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamino, T.; Miyauchi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Ishida, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Komuro, I. Endothelial Cell Senescence in Human Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002, 105, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voghel, G.; Thorin-Trescases, N.; Farhat, N.; Nguyen, A.; Villeneuve, L.; Mamarbachi, A.M.; Fortier, A.; Perrault, L.P.; Carrier, M.; Thorin, E. Cellular Senescence in Endothelial Cells from Atherosclerotic Patients Is Accelerated by Oxidative Stress Associated with Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2007, 128, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagar, N.; Naidu, G.; Panda, S.K.; Gulati, K.; Singh, R.P.; Poluri, K.M. Elucidating the Role of Chemokines in Inflammaging Associated Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2024, 220, 111944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Xie, X.; Yuan, R.; Xin, Q.; Miao, Y.; Leng, S.X.; Chen, K.; Cong, W. Vascular Aging and Atherosclerosis: A Perspective on Aging. Aging Dis 2024, 16, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Zhang, H.; Zaidi, S.A.A.; Zhou, G. Understanding the Intricacies of Cellular Senescence in Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Ageing Research Reviews 2024, 96, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, J.L.; Jørgensen, H.F. The Role of Smooth Muscle Cells in Plaque Stability: Therapeutic Targeting Potential. British Journal of Pharmacology 2019, 176, 3741–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, J. Senescence in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, G.A.; Kiss, T.; Tarantini, S.; Balasubramanian, P.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Farkas, E.; Bari, F.; Ungvari, Z.; Csiszar, A. Nrf2 Deficiency in Aged Mice Exacerbates Cellular Senescence Promoting Cerebrovascular Inflammation. GeroScience 2018, 40, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolo, E.; Badi, I.; Scavello, F.; Gambuzza, I.; Mancinelli, L.; Macrì, F.; Tedesco, C.C.; Veglia, F.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Olivieri, F.; et al. The microRNA-34a-Induced Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) Favors Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Calcification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Zhang, C.; Shuja, F.; Sturmlechner, I.; Trewartha, S.; Velasco, R.F.; Baker, D.J.; Li, H.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent Cells Suppress Innate Smooth Muscle Cell Repair Functions in Atherosclerosis. Nat Aging 2021, 1, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; van de Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.L.; van Deursen, J.M. Clearance of p16Ink4a-Positive Senescent Cells Delays Ageing-Associated Disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Schmidt, M.O.; Kallakury, B.; Jain, S.; Mehdikhani, S.; Levi, M.; Mendonca, M.; Welch, W.; Riegel, A.T.; Wilcox, C.S.; et al. Low Dose Chronic Angiotensin II Induces Selective Senescence of Kidney Endothelial Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagher, O.; Mury, P.; Thorin-Trescases, N.; Noly, P.E.; Thorin, E.; Carrier, M. Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin to Alleviate Endothelial Dysfunction in Age-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.; Konigsberg, M.; Silva-Palacios, A. Quercetin and Dasatinib, Two Powerful Senolytics in Age-Related Cardiovascular Disease. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.M.; Zhang, B.; Palmer, A.K.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Thalji, N.M.; Hagler, M.; Jurk, D.; Smith, L.A.; Casaclang-Verzosa, G.; et al. Chronic Senolytic Treatment Alleviates Established Vasomotor Dysfunction in Aged or Atherosclerotic Mice. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnewar, S.; Karnewar, V.; Shankman, L.S.; Owens, G.K. Treatment of Advanced Atherosclerotic Mice with ABT-263 Reduced Indices of Plaque Stability and Increased Mortality. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e173863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Halicka, D.; Brodsky, S.; Avram, A.; Eskander, J.; Bloomgarden, N.A.; Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Goligorsky, M.S. Contribution of p16INK4a and p21CIP1 Pathways to Induction of Premature Senescence of Human Endothelial Cells: Permissive Role of P53. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2006, 290, H1575–H1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katkenov, N.; Mukhatayev, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kushugulova, A. Systematic Review on the Role of IL-6 and IL-1β in Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Oliveira, G.; Ramos, C.; Marques, A.R.A.; Vieira, O.V. Cell Senescence, Multiple Organelle Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Cells 2020, 9, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redgrave, R.E.; Dookun, E.; Booth, L.K.; Camacho Encina, M.; Folaranmi, O.; Tual-Chalot, S.; Gill, J.H.; Owens, W.A.; Spyridopoulos, I.; Passos, J.F.; et al. Senescent Cardiomyocytes Contribute to Cardiac Dysfunction Following Myocardial Infarction. npj Aging 2023, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, P.-H.; Chen, H.-Z. Cardiomyocyte Senescence and Cellular Communications Within Myocardial Microenvironments. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianflone, E.; Torella, M.; Biamonte, F.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K.; Costanzo, F.S.; Rota, M.; Ellison-Hughes, G.M.; Torella, D. Targeting Cardiac Stem Cell Senescence to Treat Cardiac Aging and Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Sadoshima, J. Cardiomyocyte Senescence and the Potential Therapeutic Role of Senolytics in the Heart. J Cardiovasc Aging 2024, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Hodwin, B.; Ramanujam, D.; Engelhardt, S.; Sarikas, A. Essential Role for Premature Senescence of Myofibroblasts in Myocardial Fibrosis. JACC 2016, 67, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, A.B.; Shakeri, H.; Leloup, A.J.; Van Hove, C.E.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Vrints, C.J.; Lemmens, K.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M. Endothelial Senescence Contributes to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in an Aging Mouse Model. Circulation: Heart Failure 2017, 10, e003806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharagozloo, K.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Heckman, G.; Rose, R.A.; Howlett, J.; Howlett, S.E.; Nattel, S. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Elderly Population: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Considerations. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2024, 40, 1424–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Aguilar, M.; Thorin, E.; Ferbeyre, G.; Nattel, S. The Role of Cellular Senescence in Cardiac Disease: Basic Biology and Clinical Relevance. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022, 19, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Larson, D.F.; Watson, R. Age-Related Left Ventricular Function in the Mouse: Analysis Based on in Vivo Pressure-Volume Relationships. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1999, 277, H1906–H1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walaszczyk, A.; Dookun, E.; Redgrave, R.; Tual-Chalot, S.; Victorelli, S.; Spyridopoulos, I.; Owens, A.; Arthur, H.M.; Passos, J.F.; Richardson, G.D. Pharmacological Clearance of Senescent Cells Improves Survival and Recovery in Aged Mice Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, N.; Marino, F.; Scalise, M.; Salerno, L.; Molinaro, C.; Filardo, A.; Chiefalo, A.; Panuccio, G.; De Angelis, A.; Urbanek, K.; et al. Pharmacological Clearance of Senescent Cells Improves Cardiac Remodeling and Function after Myocardial Infarction in Female Aged Mice. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2022, 208, 111740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, M.J.; Zhang, X.; Kumar, A.; Atkinson, E.J.; Zhu, Y.; Jachim, S.; Mazula, D.L.; Brown, A.K.; Berning, M.; Aversa, Z.; et al. The Senescence-Associated Secretome as an Indicator of Age and Medical Risk. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e133668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, O.; Zamani, P.; Zhao, L.; Dib, M.J.; Gan, S.; Azzo, J.D.; Pourmussa, B.; Richards, A.M.; Javaheri, A.; Mann, D.L.; et al. Prognostic Significance and Biologic Associations of Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Journal of the American Heart Association 2024, 13, e033675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Zamani, P.; Salman, O.; Jehangir, Q.; Cohen, J.; Gunawardhana, K.; Greenawalt, D.; Zhao, L.; Chang, C.-P.; Gordon, D.A.; et al. Abstract 11642: Biologic Associations of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) in Heart Failure (HF): Insights From Plasma Proteomics. Circulation 2022, 146, A11642–A11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chiao, Y.A.; Clark, R.; Flynn, E.R.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Ghasemi, O.; Zouein, F.; Lindsey, M.L.; Jin, Y.-F. Deriving a Cardiac Ageing Signature to Reveal MMP-9-Dependent Inflammatory Signalling in Senescence. Cardiovascular Research 2015, 106, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.M.; Espinoza-Pérez, C.; Rimassa-Taré, C.; Machuca, V.; Bustos, J.O.; Vallejos, M.; Vargas, H.; Díaz-Araya, G. Senescent Cardiac Fibroblasts: A Key Role in Cardiac Fibrosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2023, 1869, 166642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Mackasey, M.; Tardif, J.-C.; Naud, P.; Ferbeyre, G.; Sirois, M.; Thorin, E.; Tanguay, J.-F.; Nattel, S. Abstract 11965: Cellular Senescence Produces Diastolic Dysfunction and Cardiac Hypertrophy With Aging in Mice. Circulation 2022, 146, A11965–A11965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.F.; Bonomo, C.; Guizoni, D.M.; Junior, S.A.O.; Damatto, R.L.; Cezar, M.D.M.; Lima, A.R.R.; Pagan, L.U.; Seiva, F.R.; Bueno, R.T.; et al. Modulation of MAPK and NF-κB Signaling Pathways by Antioxidant Therapy in Skeletal Muscle of Heart Failure Rats. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 39, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ha, T.; Gao, X.; Kelley, J.; Williams, D.L.; Browder, I.W.; Kao, R.L.; Li, C. NF-κB Activation Is Required for the Development of Cardiac Hypertrophy in Vivo. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2004, 287, H1712–H1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanai, E.; Frantz, S. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Comprehensive Physiology 2016, 6, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.P.; Kakkar, R.; McCarthy, C.P.; Januzzi, J.L. Inflammation in Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 75, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, X. Cellular Senescence as a Key Player in Chronic Heart Failure Pathogenesis: Unraveling Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2025, 196, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinmura, K. Cardiac Senescence, Heart Failure, and Frailty: A Triangle in Elderly People. The Keio Journal of Medicine 2016, 65, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Matsushima, S. Oxidative Stress and Heart Failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011, 301, H2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan, A.; Giugni, F.; Lamberson, V.; Yang, Y.; Boerwinkle, E.; Fornage, M.; Giannarelli, C.; Grams, M.; Windham, B.G.; Mosley, T.; et al. Abstract 4144054: Circulating Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) Proteins Are Associated with Risk of Late Life Heart Failure: The ARIC Study. Circulation 2024, 150, A4144054–A4144054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Luo, H.; Fan, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, C. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: An Update on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. Braz J Med Biol Res 2020, 53, e9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicescu, L.; Crişan, D.; Morgovan, C.; Avram, L.; Ghibu, S. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The Pathophysiological Mechanisms behind the Clinical Phenotypes and the Therapeutic Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, A.B.; Shakeri, H.; Leloup, A.J.; Van Hove, C.E.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Vrints, C.J.; Lemmens, K.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M. Endothelial Senescence Contributes to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in an Aging Mouse Model. Circ Heart Fail 2017, 10, e003806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Yan, P.; Kuchel, G.A.; Xu, M. Cellular Senescence as a Targetable Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Diseases: Therapeutic Implications: JACC Family Series. JACC: Basic to Translational Science 2024, 9, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza-Olivares, F.; Troncoso, M.F.; Pino-de la Fuente, F.; Martinez-Bilbao, J.; Riquelme, J.A.; Norambuena-Soto, I.; Villa, M.; Lavandero, S.; Castro, P.F.; Chiong, M. A Potential Role of Autophagy-Mediated Vascular Senescence in the Pathophysiology of HFpEF. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1057349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, M.O.J. Cell Senescence in Cardiometabolic Diseases. npj Aging 2024, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; Jia, C.; Sowers, J.R. Endothelial Cell Senescence in Aging-Related Vascular Dysfunction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2019, 1865, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuday, E.; Islam, T.; Kim, J.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A. Abstract 11782: Senolytic Therapy Improves Diastolic Cardiac Function in Aged Mice. Circulation 2022, 146, A11782–A11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, A.-M.; Totolici, S.; Delcea, C.; Badila, E. Biomarkers in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Perpetually Evolving Frontier. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, C.; Michaëlsson, E.; Linde, C.; Donal, E.; Daubert, J.-C.; Gan, L.-M.; Lund, L.H. Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict Heart Failure Severity and Prognosis in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics 2017, 10, e001633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, D.; Gillette, T.G.; Hill, J.A. Inflammatory Mechanisms in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Physiology (Bethesda) 2023, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Johnston, A.M.; Yiu, C.H.K.; Moreira, L.M.; Reilly, S.; Wehrens, X.H.T. Aging-Associated Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation Progression and Their Therapeutic Potential. jca 2024, 4, N. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghdiri, A. Inflammation and Arrhythmogenesis: A Narrative Review of the Complex Relationship. International Journal of Arrhythmia 2024, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengun, E.; Baggett, B.; Murphy, K.; Lu, Y.; Kim, T.-Y.; Terentyev, D.; Choi, B.-R.; Sedivy, J.; Turan, N.N.; Koren, G. Manipulating Senescence of Cardiac Fibroblasts In Vivo and In Vitro to Investigate Arrhythmogenic Effect of Senescence. The FASEB Journal 2020, 34, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Laghi-Pasini, F.; Boutjdir, M.; Capecchi, P.L. Inflammatory Cytokines and Cardiac Arrhythmias: The Lesson from COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Abbate, A.; Boutjdir, M.; Capecchi, P.L. Fir(e)Ing the Rhythm: Inflammatory Cytokines and Cardiac Arrhythmias. JACC: Basic to Translational Science 2023, 8, 728–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesus, N.M.; Wang, L.; Herren, A.W.; Wang, J.; Shenasa, F.; Bers, D.M.; Lindsey, M.L.; Ripplinger, C.M. Atherosclerosis Exacerbates Arrhythmia Following Myocardial Infarction: Role of Myocardial Inflammation. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggett, B.C.; Murphy, K.R.; Sengun, E.; Mi, E.; Cao, Y.; Turan, N.N.; Lu, Y.; Schofield, L.; Kim, T.Y.; Kabakov, A.Y.; et al. Myofibroblast Senescence Promotes Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Aged Infarcted Rabbit Heart. eLife 2023, 12, e84088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihara, K.; Sasano, T. Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alí, A.; Boutjdir, M.; Aromolaran, A.S. Cardiolipotoxicity, Inflammation, and Arrhythmias: Role for Interleukin-6 Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijman, J.; Muna, A.P.; Veleva, T.; Molina, C.E.; Sutanto, H.; Tekook, M.; Wang, Q.; Abu-Taha, I.H.; Gorka, M.; Künzel, S.; et al. Atrial Myocyte NLRP3/CaMKII Nexus Forms a Substrate for Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Res 2020, 127, 1036–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragon, R.R.; Wang, S.; Stevenson, M.D.; Lozhkin, A.; Vendrov, A.E.; Isom, L.L.; Runge, M.S.; Madamanchi, N.R. NOX4-Driven Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Aging Promotes Myocardial Remodeling and Increases Susceptibility to Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2025, 235, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, C.; Pan, Q.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Geng, J.; Xu, B. Premature Senescence of Cardiac Fibroblasts and Atrial Fibrosis in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 57981–57990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfenniger, A.; Yoo, S.; Arora, R. Oxidative Stress and Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2024, 196, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Shao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Stellate Ganglion, Inflammation, and Arrhythmias: A New Perspective on Neuroimmune Regulation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Apostolopoulos, E.J.; Apostolaki, N.E.; Melita, H.; Manolis, A.S. The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System in Cardiac Arrhythmias: The Neuro-Cardiac Axis, More Foe than Friend? Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 31, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G.M.; Whooley, M.A.; Glidden, D.V.; Pawlikowska, L.; Zaroff, J.G.; Olgin, J.E. Interleukin 6 and Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: Data from the Heart and Soul Study. Am Heart J 2008, 155, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Liu, Z.-Q.; He, P.-Y. ; Muhuyati The Role of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and PD-1 Expression on CD4 T Cells in Atrial Fibrillation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.A.; Mahmeed, W.A.; Suwaidi, J.A.; Ellahham, S. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: The Evidence. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009, 5, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saljic, A.; Heijman, J.; Dobrev, D. Emerging Antiarrhythmic Drugs for Atrial Fibrillation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angendohr, S.; Zoehner, C.; Duplessis, A.; Amin, E.; Polzin, A.; Dannenberg, L.; Schmitt, J.; Srivastava, T.; Bejinariu, A.; Rana, O.; et al. Senolysis Ameliorates Increased Susceptibility to Ventricular Arrhythmias in Prediabetes. Europace 2024, 26, euae102.624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthamil, S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Jang, H.-J.; Lyu, J.-H.; Shin, U.C.; Go, Y.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, H.G.; Park, J.H. Biomarkers of Cellular Senescence and Aging: Current State-of-the-Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Advanced Biology 2024, 8, 2400079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, R.L.; Gasek, N.S.; Kuchel, G.A.; Xu, M. The Heterogeneity of Cellular Senescence: Insights at the Single-Cell Level. Trends in Cell Biology 2023, 33, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, T.C.; Vargas, J.E.; Silva, A.O.; Fraga, L.R.; Filippi-Chiela, E. Subcellular Structure, Heterogeneity, and Plasticity of Senescent Cells. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlova, N.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Hajduch, M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, A.G.; Orlova, Y.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Novoseletskaya, E.S.; Basalova, N.A.; Alexandrushkina, N.A.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Kirillova, K.I.; Balatsky, A.V.; Samokhodskaya, L.M.; et al. Correlations between Biomarkers of Senescent Cell Accumulation at the Systemic, Tissue and Cellular Levels in Elderly Patients. Experimental Gerontology 2023, 177, 112176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Lui, L.-Y.; Zaira, A.; Mau, T.; Fielding, R.A.; Atkinson, E.J.; Patel, S.; LeBrasseur, N. Biomarkers of Cellular Senescence and Major Health Outcomes in Older Adults. Geroscience 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, J.N.; Monroe, D.G.; Atkinson, E.J.; Froemming, M.N.; Ruan, M.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Khosla, S. Characterization of Human Senescent Cell Biomarkers for Clinical Trials. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gualda, E.; Baker, A.G.; Fruk, L.; Muñoz-Espín, D. A Guide to Assessing Cellular Senescence in Vitro and in Vivo. The FEBS Journal 2021, 288, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Zamudio, R.I.; Dewald, H.K.; Vasilopoulos, T.; Gittens-Williams, L.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P.; Herbig, U. Senescence-associated Β-galactosidase Reveals the Abundance of Senescent CD8+ T Cells in Aging Humans. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, C. Transcriptomic Analysis of Cellular Senescence: One Step Closer to Senescence Atlas. Mol Cells 2021, 44, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Dong, C.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; Rabinowitz, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; He, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Novel PET Imaging Probe for Quantitative Detection of Senescence In Vivo. J Med Chem 2024, 67, 5924–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkenov, N.; Mukhatayev, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kushugulova, A. Systematic Review on the Role of IL-6 and IL-1β in Cardiovascular Diseases. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hong, D.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Da, J.; Liu, Y. Activatable Multiplexed 19F NMR Probes for Dynamic Monitoring of Biomarkers Associated with Cellular Senescence. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2024, 4, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, L.J.; Langhi Prata, L.G.P.; Bobart, S.A.; Evans, T.K.; Giorgadze, N.; Hashmi, S.K.; Herrmann, S.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Jia, Q.; Jordan, K.L.; et al. Senolytics Decrease Senescent Cells in Humans: Preliminary Report from a Clinical Trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in Individuals with Diabetic Kidney Disease. eBioMedicine 2019, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, V.R.; Palavicini, J.P.; Melendez, J.; Barthelemy, N.; He, Y.; Kautz, T.F.; Lopez-Cruzan, M.; Mathews, J.J.; Xu, P.; Zhan, B.; et al. Evaluation of Exploratory Fluid Biomarker Results from a Phase 1 Senolytic Trial in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. Res Sq, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sanoff, H.K.; Cho, H.; Burd, C.E.; Torrice, C.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Thomas, N.E.; Sharpless, N.E. Expression of p16INK4a in Peripheral Blood T-Cells Is a Biomarker of Human Aging. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, J.N.; Nambiar, A.M.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Pascual, R.; Hashmi, S.K.; Prata, L.; Masternak, M.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Musi, N.; et al. Senolytics in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Results from a First-in-Human, Open-Label, Pilot Study. eBioMedicine 2019, 40, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, W.A.; Walaszczyk, A.; Spyridopoulos, I.; Dookun, E.; Richardson, G.D. Senescence and Senolytics in Cardiovascular Disease: Promise and Potential Pitfalls. Mech Ageing Dev 2021, 198, 111540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.; Cook, S.A.; Gil, J. Therapeutic Opportunities for Senolysis in Cardiovascular Disease. The FEBS Journal 2023, 290, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadecka, A.; Nowak, N.; Bulanda, E.; Janiszewska, D.; Dudkowska, M.; Sikora, E.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A. The Senolytic Cocktail, Dasatinib and Quercetin, Impacts the Chromatin Structure of Both Young and Senescent Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. GeroScience 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadoumi, N.; Zatarah, G.; Stokar, J.; Shivam, P.; Gurt, I.; Dresner-Pollak, R. 12489 Senolytics Dasatinib And Quercetin Alleviate Type 1 Diabetes-Related Cardiac Fibrosis In Male Akita Ins-/+Mice. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2024, 8, bvae163.927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaba, M.; Iwaki, T.; Arakawa, T.; Ono, T.; Maekawa, Y.; Umemura, K. Dasatinib Suppresses Atherosclerotic Lesions by Suppressing Cholesterol Uptake in a Mouse Model of Hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2022, 149, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.-L.; Zhao, C.-H.; Yao, X.-L.; Zhang, H. Quercetin Attenuates High Fructose Feeding-Induced Atherosclerosis by Suppressing Inflammation and Apoptosis via ROS-Regulated PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 85, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.M.; Zhang, B.; Palmer, A.K.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Thalji, N.M.; Hagler, M.; Jurk, D.; Smith, L.A.; Casaclang-Verzosa, G.; et al. Chronic Senolytic Treatment Alleviates Established Vasomotor Dysfunction in Aged or Atherosclerotic Mice. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Tome, I.; Vasques-Novoa, F.; Silva, A.; Conceicao, G.; Miranda-Silva, D.; Pitrez, P.; Barros, A.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Pinto-Do-O, P.; et al. Pharmacological Targeting of Senescence with ABT-263 in Experimental Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Cardiovascular Research 2022, 118, cvac066.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Katsuumi, G.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; Minamino, T. Potential Clinical Implications of Senotherapies for Cardiovascular Disease. Circ J 2024, 88, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanović, S.D.; Thum, T.; Bauersachs, J. Anti-Senescence Therapies: A New Concept to Address Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovascular Research 2025, 121, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. Targeting Cellular Senescence with Senotherapeutics: Senolytics and Senomorphics. The FEBS Journal 2023, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgawad, I.Y.; Agostinucci, K.; Sadaf, B.; Grant, M.K.O.; Zordoky, B.N. Metformin Mitigates SASP Secretion and LPS-Triggered Hyper-Inflammation in Doxorubicin-Induced Senescent Endothelial Cells. Front. Aging 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pelletier, L.; Mantecon, M.; Gorwood, J.; Auclair, M.; Foresti, R.; Motterlini, R.; Laforge, M.; Atlan, M.; Fève, B.; Capeau, J.; et al. Metformin Alleviates Stress-Induced Cellular Senescence of Aging Human Adipose Stromal Cells and the Ensuing Adipocyte Dysfunction. eLife 2021, 10, e62635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yu, Z.; Sunchu, B.; Shoaf, J.; Dang, I.; Zhao, S.; Caples, K.; Bradley, L.; Beaver, L.M.; Ho, E.; et al. Rapamycin Inhibits the Secretory Phenotype of Senescent Cells by a Nrf2-Independent Mechanism. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesniewski, L.A.; Seals, D.R.; Walker, A.E.; Henson, G.D.; Blimline, M.W.; Trott, D.W.; Bosshardt, G.C.; LaRocca, T.J.; Lawson, B.R.; Zigler, M.C.; et al. Dietary Rapamycin Supplementation Reverses Age-Related Vascular Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress, While Modulating Nutrient-Sensing, Cell Cycle, and Senescence Pathways. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reihl, K.D.; Seals, D.R.; Henson, G.D.; LaRocca, T.J.; Magerko, K.; Bosshardt, G.C.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A.J. Dietary Rapamycin Selectively Improves Arterial Function in Old Mice. The FASEB Journal 2013, 27, 1194.17–1194.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Kim, J.; Kwon, M.; Son, Y.; Eo, S.-K.; Baryawno, N.; Kim, B.S.; Yoon, S.; Oh, S.-O.; Lee, D.; et al. Blockade of mTORC1 via Rapamycin Suppresses 27-Hydroxycholestrol-Induced Inflammatory Responses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Skike, C.E.; DeRosa, N.; Galvan, V.; Hussong, S.A. Rapamycin Restores Peripheral Blood Flow in Aged Mice and in Mouse Models of Atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s Disease. Geroscience 2023, 45, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbara, K.C.; Devnarain, N.; Owira, P.M.O. Potential Role of Polyphenolic Flavonoids as Senotherapeutic Agents in Degenerative Diseases and Geroprotection. Pharmaceut Med 2022, 36, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, S.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Darrah, M.A.; Ludwig, K.R.; VanDongen, N.S.; Greenberg, N.T.; Longtine, A.G.; Hutton, D.A.; Brunt, V.E.; Campisi, J.; et al. Intermittent Supplementation with Fisetin Improves Arterial Function in Old Mice by Decreasing Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Kirkland, J.L. Targeting Senescent Cells for a Healthier Longevity: The Roadmap for an Era of Global Aging. Life Med 2022, 1, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, K.-H.; Oh, J.; Lee, C.J.; Park, J.J.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, M.-S.; Cho, H.-J.; Choi, J.-O.; Lee, H.-Y.; Hwang, K.-K.; et al. Metformin Treatment Is Associated with Improved Survival in Diabetic Patients Hospitalized with Acute Heart Failure: A Prospective Observational Study Using the Korean Acute Heart Failure Registry Data. Diabetes & Metabolism 2024, 50, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Olesen, J.B.; Hansen, P.R.; Weeke, P.; Norgaard, M.L.; Jørgensen, C.H.; Lange, T.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Schramm, T.K.; Vaag, A.; et al. Metformin Treatment Is Associated with a Low Risk of Mortality in Diabetic Patients with Heart Failure: A Retrospective Nationwide Cohort Study. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Xie, H.; Liu, Y.; Gao, P.; Yang, X.; Shen, Z. Effect of Metformin on All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Coronary Artery Diseases: A Systematic Review and an Updated Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.N.; Grillari, J. Current Senolytics: Mode of Action, Efficacy and Limitations, and Their Future. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2024, 217, 111888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Abruzzese, E.; Latagliata, R.; Mulas, O.; Carmosino, I.; Scalzulli, E.; Bisegna, M.L.; Ielo, C.; Martelli, M.; Caocci, G.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of TKIs in Very Elderly Patients (≥75 Years) with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y. An Updated Landscape of Cellular Senescence Heterogeneity: Mechanisms, Technologies and Senotherapies. Translational Medicine of Aging 2023, 7, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Zheng, S.; Watson, M.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Gerencser, A.A.; Campisi, J.; Wirtz, D.; Wu, P.-H.; Schilling, B. Senescent Cell Heterogeneity and Responses to Senolytic Treatment Are Related to Cell Cycle Status during Cell Growth Arrest. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.M.; Kaistha, A.; Uryga, A.K.; Oc, S.; Foote, K.; Shah, A.; Finigan, A.; Figg, N.; Dobnikar, L.; Jørgensen, H.; et al. Efficacy and Limitations of Senolysis in Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 2021, 118, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Paul, K.H.; Tripathi, U.; Minamino, T.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Targeting Cell Senescence and Senolytics: Novel Interventions for Age-Related Endocrine Dysfunction. Endocrine Reviews 2024, 45, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, L.; Makarczyk, M.J.; Feng, P.; Zhang, J. The Anti-Aging Mechanism of Metformin: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basisty, N.; Kale, A.; Jeon, O.H.; Kuehnemann, C.; Payne, T.; Rao, C.; Holtz, A.; Shah, S.; Sharma, V.; Ferrucci, L.; et al. A Proteomic Atlas of Senescence-Associated Secretomes for Aging Biomarker Development. PLOS Biology 2020, 18, e3000599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.I.; Islam, M.T.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A.J. Mechanisms and Consequences of Endothelial Cell Senescence. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.; Shvedova, M.; Thanapaul, R.J.R.S.; Botchkarev, V.; Roh, D. Epigenetic Regulation of Cellular Senescence. Cells 2022, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwan-Zaiter, H.; Wagner, N.; Michiels, J.-F.; Wagner, K.-D. Dynamic Spatiotemporal Expression Pattern of the Senescence-Associated Factor p16Ink4a in Development and Aging. Cells 2022, 11, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasegaran, S.; Sluka, J.P.; Shanley, D. Modelling the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Senescent Cells in Wound Healing, Chronic Wounds, and Fibrosis. PLOS Computational Biology 2025, 21, e1012298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, R.; Yang, J.; Koplev, S.; An, M.C.; Patel, P.L.; O’Brien, R.N.; Dubose, B.N.; Dodatko, T.; Rogatsky, E.; Sukhavasi, K.; et al. Integration of Transcriptomes of Senescent Cell Models with Multi-Tissue Patient Samples Reveals Reduced COL6A3 as an Inducer of Senescence. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, C.S.L.; Luesken, S.W.M.; Waaijer, M.E.C.; Maier, A.B. Senescence in Tissue Samples of Humans with Age-Related Diseases: A Systematic Review. Ageing Research Reviews 2021, 68, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, B.; Tadi, P. Physiology, Aging. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging and Age-Related Disorders. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, I.; Jain, S.M.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Pathak, S.; Banerjee, A.; Rawat, S.; Sharma, N.R.; Duttaroy, A.K. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Its Association with Age-Related Disorders. Front Physiol 2024, 15, 1384966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, J.A.; Coppotelli, G.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Ross, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Mitochondrial and Metabolic Dysfunction in Ageing and Age-Related Diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, M.; Crisci, G.; Armentaro, G.; Cicco, S.; Talerico, G.; Bobbio, E.; Lanzafame, L.; Green, C.G.; McLellan, A.G.; Debiec, R.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction—An Updated Review of the Literature. Life (Basel) 2023, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, C.; Pagliaro, P. Endothelial Dysfunction: Redox Imbalance, NLRP3 Inflammasome, and Inflammatory Responses in Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-K.; Wang, C.-Y. Telomeres and Telomerase in Cardiovascular Diseases. Genes (Basel) 2016, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, H.; Lefevre, L.; Sayir, S.; Itier, R.; Maggiorani, D.; Dutaur, M.; Marsal, D.J.; Roncalli, J.; Pizzinat, N.; Cussac, D.; et al. Selective Cardiomyocyte Oxidative Stress Leads to Bystander Senescence of Cardiac Stromal Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.; Wordsworth, J.; Wang, C.; Jurk, D.; Lawless, C.; Martin-Ruiz, C.; von Zglinicki, T. A Senescent Cell Bystander Effect: Senescence-Induced Senescence. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidler, C.; Kovalchuk, O.; Kovalchuk, I. Epigenetic Regulation of Cellular Senescence and Aging. Front. Genet. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.C. Nutrient Sensing, Signaling and Ageing: The Role of IGF-1 and mTOR in Ageing and Age-Related Disease. Subcell Biochem 2018, 90, 49–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshgar, N.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Dai, D.-F. TOR Signaling Pathway in Cardiac Aging and Heart Failure. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SASP Molecule | Molecular Class | Primary Role in Senescence and Tissue Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Cytokine | Central mediator of chronic inflammation; promotes paracrine senescence via JAK/STAT pathway; impairs endothelial function and insulin signaling. |

| IL-1α / IL-1β | Cytokine | Early SASP inducers; amplify NF-κB signaling; enhance MMP expression and leukocyte recruitment; activate inflammasome. |

| TNF-α | Cytokine | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; disrupts cell-cell junctions; enhances ROS production and apoptosis in neighboring cells. |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | Chemokine | Chemoattractant for neutrophils; promotes angiogenesis and inflammatory cell infiltration; contributes to plaque instability. |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | Chemokine | Recruits monocytes/macrophages to sites of tissue injury or senescence; drives chronic inflammation and foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. |

| CCL5 (RANTES) | Chemokine | Attracts T cells and monocytes; involved in autoimmune and chronic inflammatory responses in vascular aging. |

| MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9 | Matrix Metalloproteinases | Degrade extracellular matrix; facilitate tissue remodeling, fibrosis, and plaque rupture; destabilize fibrous caps in atherosclerosis. |

| GM-CSF | Growth Factor / Cytokine | Promotes myeloid lineage differentiation; enhances pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization and activation. |

| TGF-β | Growth Factor | Dual role in senescence and fibrosis; induces ECM deposition; contributes to cardiac and vascular fibrosis and stiffening. |

| VEGF | Growth Factor | Promotes angiogenesis; contributes to neovascularization of plaques; involved in tissue repair and endothelial permeability. |

| IGFBP-3 / IGFBP-7 | Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins | Modulate IGF signaling; induce growth arrest; IGFBP-7 implicated in paracrine senescence and cardiac hypertrophy. |

| PAI-1 (SERPINE1) | Serine Protease Inhibitor | Mediator of TGF-β-induced senescence; inhibits fibrinolysis; associated with thrombosis and vascular remodeling in aged tissues. |

| Galectin-3 | Lectin | Promotes inflammation, fibrosis, and immune cell recruitment; elevated in heart failure and linked to SASP signaling. |

| HMGB1 | Alarmin / DAMP | Released during cellular stress or necrosis; triggers TLR4 signaling and promotes inflammatory SASP amplification. |

| SAA1 / SAA2 | Acute-Phase Proteins | Amplify inflammatory responses; stimulate chemokine production and monocyte recruitment. |

| IL-10 | Anti-inflammatory Cytokine | Context-dependent; may limit excessive inflammation but also contribute to immune evasion by senescent cells. |

| ROS / NO | Reactive Species | Promote DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and SASP induction; disrupt redox-sensitive ion channels and gap junctions. |

| Extracellular vesicles (EVs) | Nanoparticle-derived SASP | Transfer of microRNAs, damaged DNA, and inflammatory proteins to nearby cells; propagate senescence and SASP signaling systemically. |

| Feature | Transient SASP | Chronic SASP |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering Context | Acute stress (e.g., wound healing, development, tumor suppression) | Persistent stress or damage (e.g., telomere attrition, DNA damage, oxidative stress) |

| Duration of SASP Expression | Short-lived; resolves within days to weeks | Long-lasting; persists over weeks to months or indefinitely |

| Senescent Cell Fate | Often cleared by immune surveillance or undergoes apoptosis | Resistant to apoptosis; persists and accumulates with age |

| Key SASP Components | Controlled expression of IL-6, IL-8, TGF-β, limited MMPs | Broad, high-level expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α), MMPs, chemokines |

| Immune Modulation | Immunostimulatory; facilitates immune cell recruitment and clearance of senescent cells | Immunosuppressive or immunoevasive; leads to immune cell exhaustion and chronic inflammation |

| Paracrine Effects | Promotes transient proliferation, differentiation, or repair in neighboring cells | Induces paracrine senescence, inflammation, and tissue degradation in surrounding cells |

| Tissue Remodeling | Supports tissue regeneration and fibrosis resolution | Promotes fibrosis, ECM degradation, calcification, and loss of tissue integrity |

| NF-κB / p38MAPK Activation | Mild, transient activation | Sustained, amplified activation driving long-term SASP transcription |

| DNA Damage Response (DDR) | Temporary DDR activation | Persistent DDR signaling (e.g., γ-H2AX, ATM/ATR activation) |

| Epigenetic Landscape | Reversible chromatin changes (transient enhancer activation) | Stable heterochromatin formation (SAHF), long-term enhancer remodeling of SASP genes |

| Metabolic Signature | Mild metabolic reprogramming | Elevated glycolysis, mitochondrial dysfunction, increased ROS production |

| Relevance to CVD | Protective in early repair post-injury (e.g., myocardial infarction) | Pathogenic in aging-associated diseases: atherosclerosis, HFpEF, vascular calcification |

| Resolution Mechanism | Clearance by immune cells (NK, macrophages) | Immune evasion or exhaustion prevents clearance, leading to accumulation |

| Therapeutic Implications | May be beneficial and should be preserved | Targeted for removal or suppression using senolytics or senomorphics |

| Disease/Condition | Key SASP-Mediated Mechanisms | Prominent SASP Components | Pathophysiological Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | SASP-induced endothelial dysfunction reduces nitric oxide (NO); vascular senescence increases stiffness and tone | IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β, ROS, MCP-1, MMPs, PAI-1 | Arterial stiffness, impaired vasodilation, increased systemic vascular resistance, pressure overload |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD) | Chronic inflammation in peripheral arteries; endothelial senescence impairs angiogenesis and perfusion | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, MMP-9, CCL2 | Capillary rarefaction, impaired collateral vessel formation, limb ischemia, tissue necrosis |

| Atherosclerosis | Senescent endothelial and smooth muscle cells promote lipid accumulation, inflammation, and matrix degradation | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TNF-α, MMP-1/3/9, TGF-β | Plaque growth, immune cell recruitment, necrotic core expansion, and fibrous cap weakening |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | SASP enhances leukocyte adhesion and endothelial dysfunction in coronary vessels; promotes thrombosis | IL-6, TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, PAI-1, ROS | Reduced coronary perfusion, enhanced vasoconstriction, increased risk of plaque rupture and thrombus |

| Myocardial Infarction (MI) | Post-MI, SASP from senescent fibroblasts and immune cells sustains inflammation and impairs reparative remodeling | IL-1β, IL-6, TGF-β, MMPs, HMGB1 | Excessive fibrosis, impaired scar formation, ventricular dysfunction, higher risk of rupture |

| Heart Failure (HF) | Persistent SASP drives myocardial fibrosis, hypertrophy, and impaired cardiomyocyte contractility | TGF-β, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, MMPs, IGFBP-3 | Left ventricular stiffening, diastolic dysfunction, progression of HFpEF and HFrEF |

| Cardiac Arrhythmias | SASP-induced fibrosis and inflammation disrupt electrical conduction and calcium homeostasis | IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, ROS, MMP-9, TGF-β | Gap junction uncoupling, Ca²⁺ handling defects, increased risk of atrial fibrillation and VT/VF |

| Biomarker | Biomarker Class | Source | Biological Relevance | Advantages / Limitations | Utility in CVD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | SASP cytokine | Plasma / serum | Key pro-inflammatory SASP cytokine; drives systemic inflammaging via JAK/STAT pathway | Readily measurable; non-specific; elevated in many chronic conditions | Correlates with endothelial dysfunction, heart failure progression, and increased CVD mortality |

| IL-1β | SASP cytokine | Plasma / serum | Early SASP mediator; activates NF-κB and inflammasome | Reflects acute and chronic inflammation; overlap with infection signals | Linked to myocardial remodeling, atherosclerosis, and atrial fibrillation |

| TNF-α | SASP cytokine | Plasma / serum | Pro-inflammatory cytokine that promotes apoptosis, insulin resistance | Robust inflammatory marker; limited specificity | Predicts heart failure risk, myocardial fibrosis, and vascular dysfunction |

| MMP-1 / MMP-3 / MMP-9 | SASP protease | Plasma / tissue biopsies | Mediate ECM degradation, fibrosis, plaque rupture | Specific to tissue remodeling; can reflect active SASP | Associated with atherosclerosis progression, plaque instability, and myocardial fibrosis |

| PAI-1 (SERPINE1) | SASP effector / ECM regulator | Plasma / endothelial cells | Mediator of TGF-β-induced senescence; pro-thrombotic and fibrotic | Strongly associated with senescence; modulated by metabolic status | Marker of vascular senescence, pro-coagulant state, and hypertensive remodeling |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | SASP chemokine | Plasma / PBMCs | Neutrophil chemoattractant; promotes leukocyte adhesion and chronic inflammation | Reflects SASP-driven immune cell recruitment; overlaps with acute inflammation markers | Elevated in unstable atherosclerosis and heart failure |

| HMGB1 | DAMP / Alarmin | Plasma / extracellular vesicles | Released from stressed or senescent cells; promotes sterile inflammation | Non-specific damage signal; also elevated in necrosis | Linked to post-MI inflammation, cardiac injury, and chronic heart failure |

| p16INK4a mRNA | Senescence marker | PBMCs / tissue biopsy | CDK inhibitor upregulated in senescent cells; cell-cycle arrest marker | Correlates with biological age; requires RNA quantification | Elevated in vascular and myocardial senescence; correlates with frailty and arterial aging |

| p21CIP1 | Senescence marker | PBMCs / tissue | DNA damage-induced CDK inhibitor; involved in early senescence | Reflects stress-induced senescence; overlap with quiescence | Associated with endothelial and fibroblast senescence in CVD |

| γ-H2AX foci | DNA damage marker | PBMCs / tissue nuclei | Histone mark of DNA double-strand breaks; persistent in senescent cells | Requires microscopy or imaging; gold-standard for DNA damage | Identifies cells with persistent DDR driving SASP in vascular and cardiac tissues |

| SA-β-Gal activity | Senescence enzymatic marker | Tissue biopsy / ex vivo cultures | Classic marker of lysosomal β-galactosidase upregulation in senescence | Requires fresh tissue or cells; limited in vivo applicability | Used in histological assessment of vascular and myocardial senescence |

| SASP Proteomic Panels | Multi-analyte | Plasma / serum | Combines IL-6, IL-8, MMPs, IGFBPs, TGF-β, PAI-1, etc. | Captures SASP complexity; multiplexed detection; requires standardization | Correlates with disease burden, biological age, and therapeutic response to senolytics |

| Circulating microRNAs | Non-coding RNA biomarkers | Plasma / extracellular vesicles | miRNAs involved in senescence regulation and secreted via EVs (e.g., miR-34a, miR-146a) | Non-invasive; still under investigation; may reflect specific SASP profiles | Linked to cardiac remodeling, fibrosis, and endothelial senescence |

| Cell-free mitochondrial DNA (cf-mtDNA) | Cell stress marker | Plasma | Released from damaged or senescent cells; activates cGAS-STING pathway | Reflects systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress | Elevated in patients with HFpEF, MI, and vascular inflammation |

| Epigenetic Clocks (e.g., DNAm Age) | DNA methylation signature | Blood / saliva / tissues | Measures biological age acceleration via methylation at age-related CpG sites | Requires sequencing; validated in aging studies | Associated with vascular aging, arterial stiffness, and CVD risk beyond chronological age |

| Senolytic Agent | Mechanism of Action | Senescent Cell Targets | Evidence in CVD Models | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dasatinib (D) | Inhibits multiple tyrosine kinases (e.g., Src, EphA) required for senescent cell survival | Senescent preadipocytes, endothelial cells, VSMCs, macrophages | Reduces atherosclerosis and improves cardiac function in aged and hyperlipidemic mice | Clinical trials (e.g., diabetic kidney disease) |

| Quercetin (Q) | Inhibits PI3K, serpins, and BCL-2 family proteins; antioxidant properties | Endothelial cells, VSMCs | Improves endothelial function and reduces arterial stiffness | Used in combination with D (D+Q); ongoing trials |

| Navitoclax (ABT-263) | BCL-2/BCL-xL inhibitor; induces apoptosis in cells relying on anti-apoptotic signaling | Senescent endothelial cells, VSMCs, cardiomyocytes | Reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac function in aged mice | Preclinical; dose-limiting thrombocytopenia |

| Fisetin | Flavonoid with senolytic and antioxidant activity; modulates PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling | Multiple senescent cell types | Reduces SASP expression, vascular inflammation, and improves survival in aged mice | Clinical trials in aging and frailty |

| UBX1325 / UBX0101 | Small molecules targeting pro-survival pathways (e.g., FOXO4-p53 interaction) | Chondrocytes, fibroblasts, possibly cardiac fibroblasts | UBX0101 shown to clear senescent fibroblasts in OA models; cardiovascular applications under investigation | Phase 1/2 trials for other diseases |

| FOXO4-DRI peptide | Disrupts FOXO4–p53 interaction, restoring p53-mediated apoptosis in senescent cells | Fibroblasts, endothelial cells | Restores cardiac function and decreases senescent cell burden in progeroid mouse models | Preclinical; limited by delivery challenges |

| Piperlongumine | Increases ROS selectively in senescent cells, triggering apoptosis | Broad senescent cell activity | Potential anti-fibrotic effects in cardiac remodeling; requires further CVD-specific validation | Preclinical |

| BPTES (Glutaminase inhibitor) | Inhibits glutamine metabolism, selectively killing glutamine-addicted senescent cells | Cancer-associated fibroblasts, senescent endothelial cells | May reduce metabolic-driven vascular senescence; under investigation | Experimental stage |

| HSP90 inhibitors (e.g., 17-AAG) | Destabilize survival proteins (e.g., AKT, HIF1α) in senescent cells | Multiple senescent types | Shown to deplete senescent cells in vitro and attenuate stress-induced vascular damage | Preclinical; toxicity concerns |

| Emerging PROTAC-based senolytics | Use proteolysis-targeting chimeras to degrade senescence-specific survival proteins | Customizable based on target (e.g., p16INK4a+, p21CIP1+ cells) | Potential for tissue- and cell-specific clearance of senescent cardiovascular cells | Early-stage development |

| Senomorphic Agent | Mechanism of Action | Target Pathways | Effects on SASP / Senescence | Potential Role in CVD | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin (Sirolimus) | Inhibits mTORC1 signaling | mTOR/PI3K/AKT pathway | Reduces translation of SASP mRNAs, suppresses IL-6, IL-1β, MMPs | Attenuates vascular aging, cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis; improves diastolic function | Clinical trials in aging and HFpEF |

| Metformin | Activates AMPK; inhibits mitochondrial complex I and mTOR | AMPK, NF-κB, mTOR | Suppresses SASP cytokines, enhances autophagy, reduces oxidative stress | Reduces endothelial senescence, improves vascular reactivity, lowers inflammatory markers in elderly | Widely used; repurposing trials ongoing |

| Resveratrol | Activates SIRT1; modulates NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome | SIRT1, AMPK, NF-κB | Reduces IL-6, TNF-α, and ROS; enhances mitochondrial function | Protects against endothelial dysfunction, reduces arterial stiffness and inflammation | Nutraceutical; variable bioavailability |

| Curcumin | Inhibits NF-κB and p38 MAPK; antioxidant | NF-κB, p38 MAPK | Reduces SASP cytokine output, MMPs, and ROS | Improves vascular reactivity; anti-fibrotic effects in myocardium | Preclinical and nutraceutical use |

| Apigenin | Flavonoid; inhibits NF-κB and cyclin-dependent kinases | CDK1/2, NF-κB | Suppresses pro-inflammatory SASP components and DNA damage signaling | Reduces oxidative stress and inflammation in vascular tissues | Preclinical |

| Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) | NAD⁺ precursor; enhances mitochondrial function | SIRT1, PARP, mitochondrial pathways | Reduces mitochondrial-derived SASP signaling; promotes DNA repair | Reverses age-associated endothelial dysfunction; improves arterial compliance | In trials for metabolic and cardiac aging |

| JAK inhibitors (e.g., Ruxolitinib) | Inhibit JAK/STAT signaling downstream of SASP cytokines | JAK/STAT pathway | Reduces IL-6–driven inflammatory SASP output | Mitigates cardiac inflammation and hypertrophy in aged hearts; potential use in HFpEF | Approved for myelofibrosis; trials in aging |

| Glycyrrhizin | Inhibits HMGB1–TLR4 signaling | DAMP sensing (TLRs) | Suppresses SASP-induced sterile inflammation | Reduces inflammatory cardiomyopathy; protects against ischemia–reperfusion injury | Experimental |

| Bay 11-7082 | Irreversible inhibitor of IκB kinase (IKK) | NF-κB signaling | Suppresses NF-κB-dependent SASP gene expression | Reduces vascular inflammation and remodeling | Preclinical |

| Melatonin | Antioxidant and chronobiotic; modulates NF-κB, NLRP3, SIRT1 | NLRP3, SIRT1, ROS | Reduces pro-inflammatory SASP expression; promotes anti-inflammatory cytokines | Protects cardiac tissue from oxidative damage and fibrotic remodeling | Clinical use for sleep; trials ongoing in aging |

| Spermidine | Enhances autophagy and mitochondrial proteostasis | Autophagy, mTOR, AMPK | Suppresses pro-inflammatory and metabolic SASP profiles | Improves cardiac diastolic function and mitochondrial function in aging myocardium | Trials in cardiovascular aging |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).