1. Introduction

inflammatory drug (NSAID) effectively used for pain management and inflammatory conditions [

1]. Despite its therapeutic benefits, ibuprofen is known to be susceptible to various degradation pathways, including hydrolysis, oxidation, and photolysis, which can compromise its pharmaceutical stability and lead to the formation of potentially toxic degradants within dosage forms [

2,

3]. Traditional experimental methods for studying drug degradation, such as accelerated stability testing, are often time-consuming, expensive, and may offer limited mechanistic insight, particularly in identifying minor degradants [

4].

Recent studies have investigated the oxidative degradation mechanisms of ibuprofen using experimental and computational approaches [

5,

6]. Hydroxyl radical (•OH) initiated degradation was found to be the primary pathway, with H-atom abstraction being the most favorable mechanism [

6,

7]. The UV/H2O2 process was effective for ibuprofen degradation, with •OH playing a crucial role in the transformation of both ibuprofen and its byproducts [

5]. Density functional theory calculations provided insights into the thermodynamics and kinetics of ibuprofen’s reactions with •OH and sulfate radical anion (SO4•-), revealing that H-atom abstraction pathways were energetically favored for both radicals [

6]. The calculated rate constants for ibuprofen’s reaction with •OH were consistent with experimental values, ranging from 3.43 × 10⁹ to 6.72 × 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [

6,

8]. These studies provide valuable insights into ibuprofen’s degradation mechanisms and potential byproduct formation.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become a powerful tool in computational chemistry, offering atomic-level insights into molecular structures and properties [

9]. Based on the electron density distribution rather than the many-electron wave function, DFT provides an efficient alternative to traditional quantum mechanical methods [

10]. Its favorable price-performance ratio allows for the study of large-scale molecular systems with sufficient accuracy [

9]. DFT has diverse applications, including drug design and formulation optimization in pharmaceutical sciences [

11]. It enables the prediction of co-crystallization, optimization of nanodelivery systems, and evaluation of drug release kinetics [

11]. Despite challenges in dynamic simulations of complex environments, DFT’s integration with other computational methods has led to significant breakthroughs [

11]. Its wide-ranging applications and effectiveness have made it an invaluable tool for chemists solving chemical problems [

12].

Previous computational studies have explored degradation pathways of various pharmaceuticals. For example, DFT has been used to investigate the photodegradation of drugs in aqueous environments [

13,

14] and to predict degradation mechanisms of pollutants [

5]. While these studies demonstrate the utility of computational methods, a comprehensive molecular modelling investigation specifically focused on the oxidative degradation mechanism of ibuprofen remains less explored in detail. Understanding such mechanisms at a quantum chemical level can directly inform the development of more stable pharmaceutical formulations, ultimately enhancing drug quality and safety.

This study aims to bridge this knowledge gap by employing DFT to determine a plausible oxidative degradation mechanism for ibuprofen. Specifically, the objectives of this research were to:

Investigate the electronic properties and reactivity descriptors of ibuprofen using quantum chemical calculations.

Identify key reactive sites and susceptible bonds within the ibuprofen molecule under oxidative conditions.

Propose a detailed molecular-level oxidative degradation mechanism for ibuprofen based on computational predictions.

The findings from this molecular modelling approach are expected to provide critical insights for optimizing ibuprofen formulations, thereby mitigating degradation and improving drug stability.

2. Results

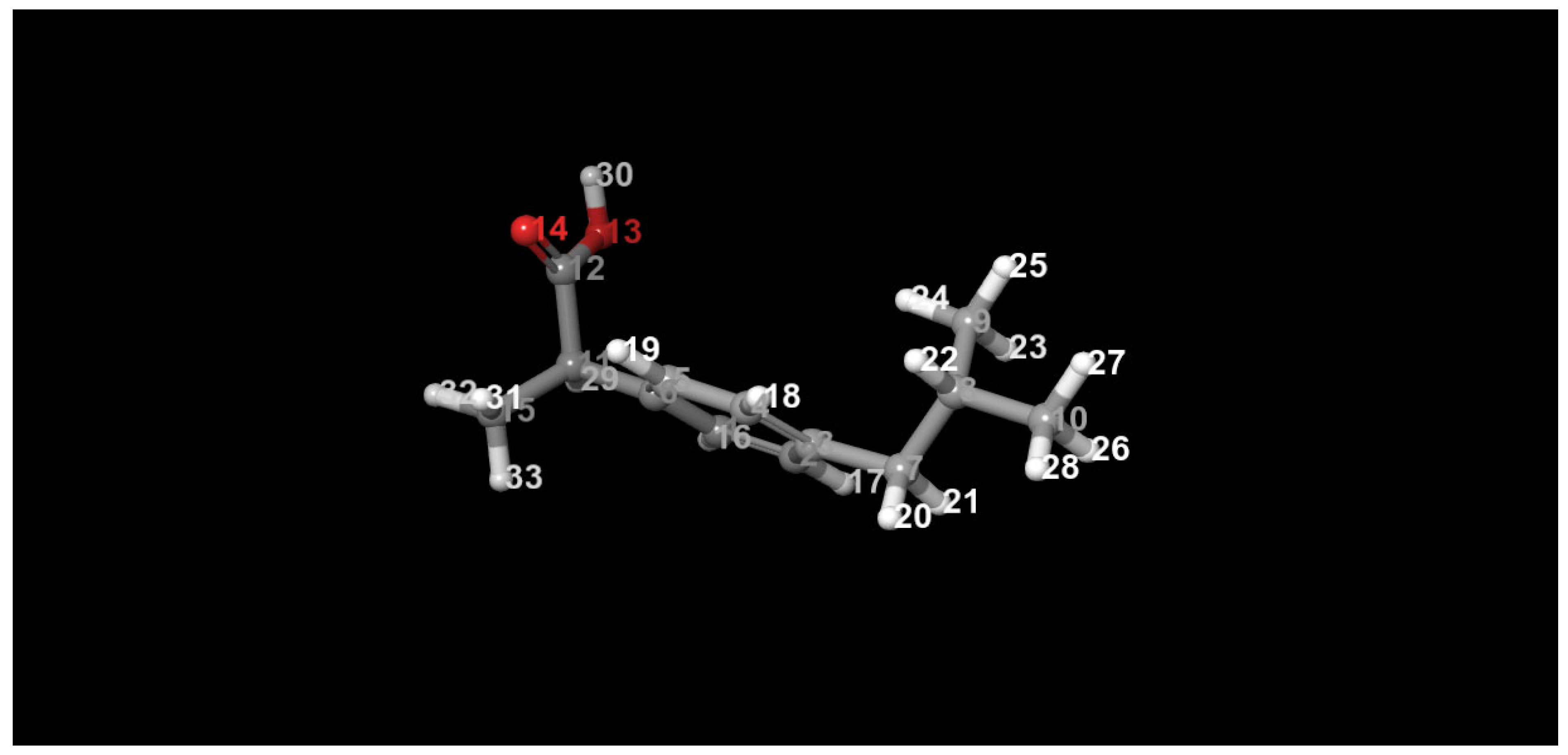

2.1. Geometry Optimization

The geometry of ibuprofen was optimized to its lowest-energy conformation using the B3LYP-D3/6-31G** level of theory. The optimized structure was validated through comparison of bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles against both experimental data and non-optimized structures (see

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). The data showed close agreement with experimental values, confirming the reliability of the computational model. Notably, deviations observed in certain torsional and bond angles—such as O14–C12–C11–C6 and C6–C11–C14–H20—suggest regions of potential strain that may be more susceptible to oxidative attack. These geometrical distortions may influence the molecule’s overall stability and chemical reactivity

Figure 1.

Geometry optimized ibuprofen structure.

Figure 1.

Geometry optimized ibuprofen structure.

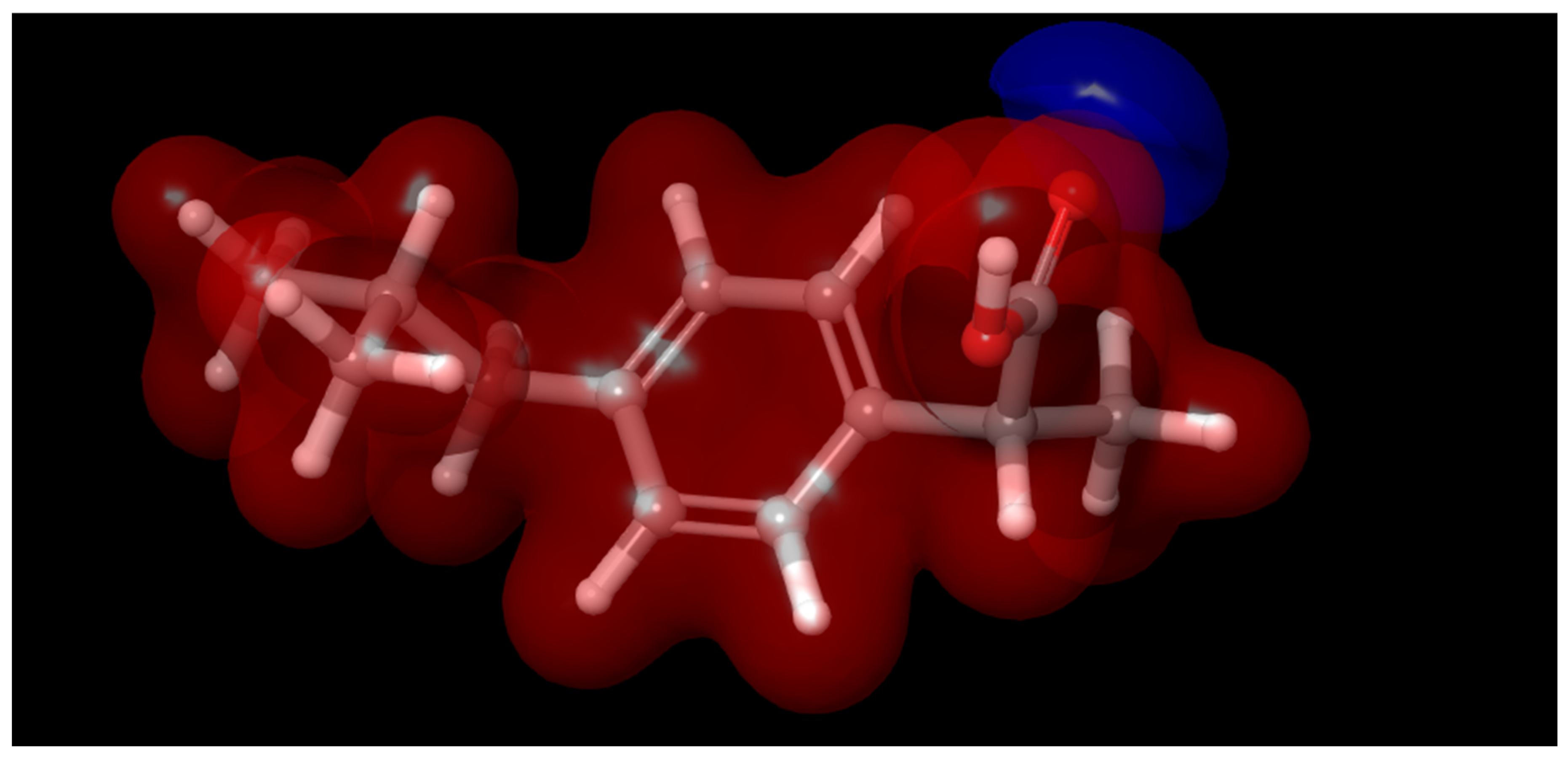

2.2. HOMO-LUMO Energy Gap Calculations

The calculated HOMO–LUMO energy gap for ibuprofen was 0.27715 kcal/mol (

Table 4), indicating a relatively low kinetic stability and a high susceptibility to electronic excitation. Such a narrow energy gap suggests that ibuprofen can undergo electronic transitions with minimal energy input, rendering it more reactive under photochemical or oxidative conditions. The HOMO (–0.31692 kcal/mol) and LUMO (0.03977 kcal/mol) energy levels describe the molecule’s ability to donate and accept electrons, respectively, thereby influencing its reactivity with nucleophiles and electrophiles.

Furthermore, the average electrostatic potential map (

Figure 2) highlights regions of high and low electron density across the ibuprofen molecule. These regions correspond to potential reactive sites and provide visual support for understanding how the HOMO and LUMO distributions may influence the degradation pathway..

Table 4.

HOMO-LUMO energy gap calculations.

Table 4.

HOMO-LUMO energy gap calculations.

| |

kcal/mol |

| HOMO |

-0.31692 |

| LUMO |

0.03977 |

| HOMO-LUMO Energy gap |

0.27715 |

Figure 2.

Average electrostatic potential map of ibuprofen. .

Figure 2.

Average electrostatic potential map of ibuprofen. .

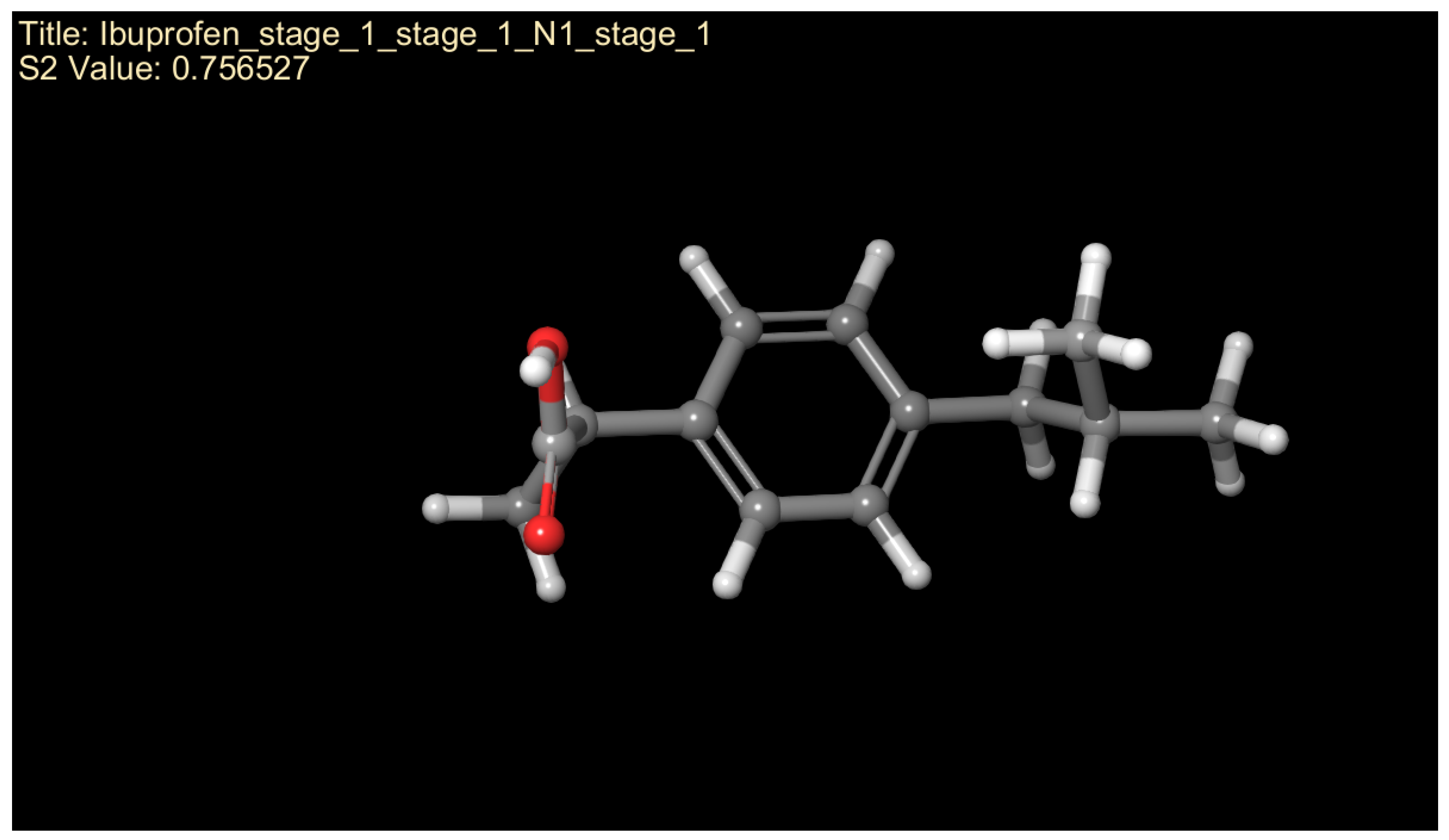

2.3. Fukui Functions Results

The analysis of Fukui functions provided detailed insight into the local reactivity of ibuprofen, identifying specific atomic sites prone to electrophilic or nucleophilic attack (

Figure 3). Fukui functions quantify the change in electron density upon electron addition (f⁻) or removal (f⁺), enabling prediction of reactive sites within a molecule. Regions with high positive f⁺ values are favorable for nucleophilic attack, while areas with high negative f⁻ values are more susceptible to electrophilic attack [

24,

25]. In the case of ibuprofen, the carboxylic acid group exhibited the highest reactivity, consistent with experimental reports highlighting its role in degradation pathways. This computational observation is reinforced by the calculated global softness value, which reflects the molecule’s overall polarizability and readiness to undergo electronic perturbations. Together, the Fukui function isosurfaces and global descriptors offer a comprehensive view of ibuprofen’s chemical reactivity profile and potential degradation hotspots. [

26].

Figure 3.

The global softness value and Fukui function isosurfaces for ibuprofen.

Figure 3.

The global softness value and Fukui function isosurfaces for ibuprofen.

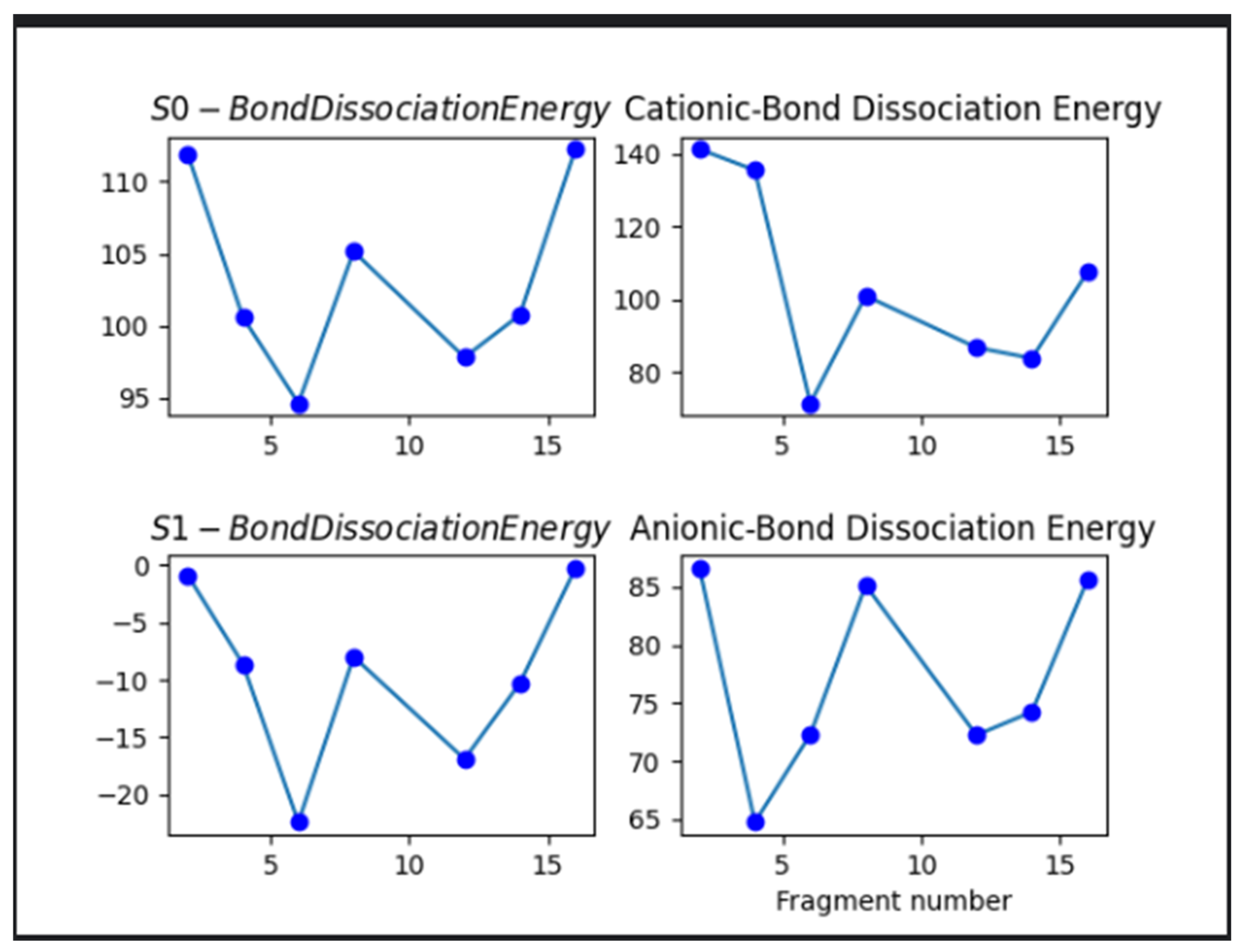

2.4. Bond Dissociation Energy Results

Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) calculations were performed on relevant bonds within the ibuprofen molecule to quantitatively assess their stability. The results, summarized in

Table 5 and illustrated in

Figure 4, identified the O14–C12–C11 bond as particularly susceptible to cleavage under oxidative conditions, displaying the lowest BDE value among the bonds analyzed. This indicates a primary point of vulnerability to attack by reactive oxidative species [

27]. Analysis across different electronic states revealed significant differences in bond stability. In the excited state (S₁), ibuprofen exhibited substantially reduced BDEs, with several values falling below 0 kcal/mol, indicating a high propensity for bond cleavage and photodegradation. The anionic form of ibuprofen also showed relatively low BDEs, ranging between approximately 20–90 kcal/mol, suggesting increased susceptibility to degradation compared to the ground state and cationic ffor [

28]. In contrast, most BDEs in the ground state were above 95 kcal/mol, which aligns with literature-defined thresholds for autoxidative resistance in organic compounds. However, the presence of one bond with a BDE slightly below this threshold indicates that even ground-state ibuprofen is not completely resistant to oxidative degradation. These findings emphasize the utility of BDE analysis in identifying weak points in the molecule’s structure that may initiate degradation under various environmental or oxidative stress conditions.

Table 5.

Bond dissociation energy results.

Table 5.

Bond dissociation energy results.

| Fragment number |

S0- Bond Dissociation Energy |

S1-Bond Dissociation Energy |

Cation- Bond Dissociation Energy |

Anion-Bond Dissociation Energy |

| 2 |

111.944364 |

-0.847896 |

141.151429 |

86.600583 |

| 4 |

100.582244 |

-8.609268 |

135.404599 |

64.756574 |

| 6 |

94.601 |

-22.414885 |

71.444394 |

72.305489 |

| 8 |

105.13944 |

-7.989959 |

100.925313 |

85.132740 |

| 12 |

97.7935077 |

-16.897899 |

86.727571 |

72.253493 |

| 14 |

100.742509 |

-10.283207 |

83.777848 |

72.253493 |

| 16 |

112.253409 |

-0.273447 |

107.415848 |

86.600583 |

Figure 4.

Subplots of bond dissociation energies of all states of ibuprofen. .

Figure 4.

Subplots of bond dissociation energies of all states of ibuprofen. .

From the bond dissociation shown in the subplots above the excited state ibuprofen require less energy indicated by the bond dissociation energies less than zero to negative twenty for breaking the bonds into various fragments. This shows that ibuprofen in its excited state is more likely to undergo degradation transformations. The anionic ibuprofen form follows the excited ibuprofen form with bond dissociation ranging from ninety to twenty kcal/mol. This suggests that ibuprofen in its anionic form is more likely to undergo degradation transformation as compared to the cationic and the ground state form. On the other hand, the bond dissociation energy of ibuprofen is more stable towards degradation reactions relative to its other forms as indicated by most of its bond dissociation energies above 95kcals/mol. However, it is susceptible to oxidative degradation since it has one bond dissociation energy less than 95kcals/mol the threshold value for autoxidative degradation reported in literature for most organic compounds including ibuprofen.

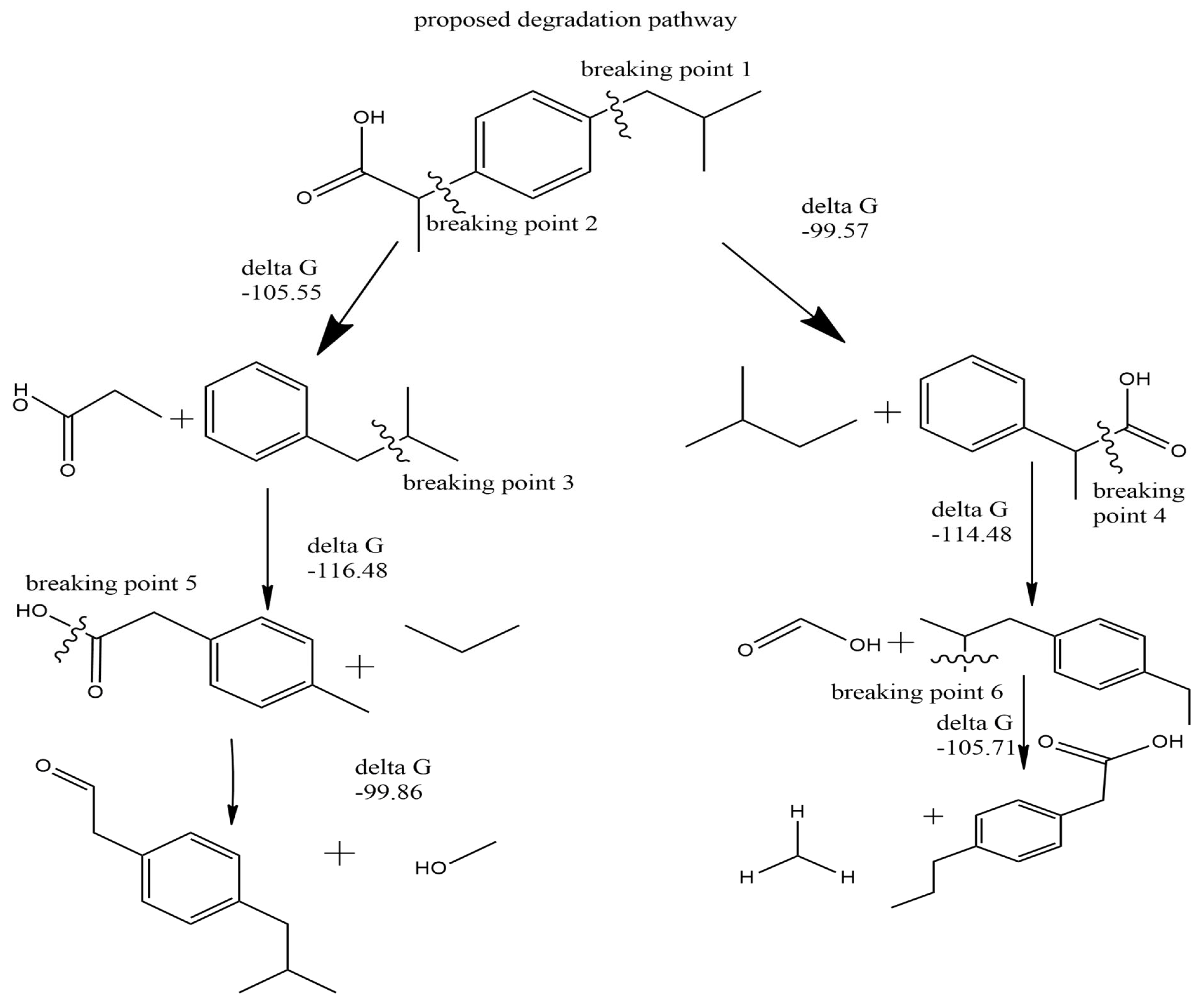

2.5. Proposed Oxidative Degradation Mechanism

Based on the comprehensive quantum chemical calculations, a plausible oxidative degradation mechanism for ibuprofen is proposed (

Figure 12). The integration of geometry optimization, HOMO–LUMO analysis, Fukui functions, and bond dissociation energy (BDE) calculations consistently identifies the carboxylic acid group and the O14–C12–C11 bond within the side chain as the primary sites of oxidative attack. The low HOMO–LUMO energy gap suggests high reactivity, while Fukui function analysis highlights susceptibility to electrophilic attack at the carboxyl group. Additionally, the low BDE of the O14–C12–C11 bond in multiple electronic states (ground: 111.94 kcal/mol; excited: –0.85 kcal/mol; cation: 141.15 kcal/mol; anion: 86.60 kcal/mol) confirms its vulnerability to homolytic cleavage. These findings align with experimental degradation products involving the propionic acid moiety. Understanding this degradation mechanism at the molecular level can support the design of more stable formulations through molecular modification or incorporation of protective excipients like antioxidants [

26,

29]. Understanding this mechanism at a molecular level is crucial for designing more stable formulations by incorporating antioxidants or modifying the molecular structure to sterically hinder or electronically protect these susceptible sites.

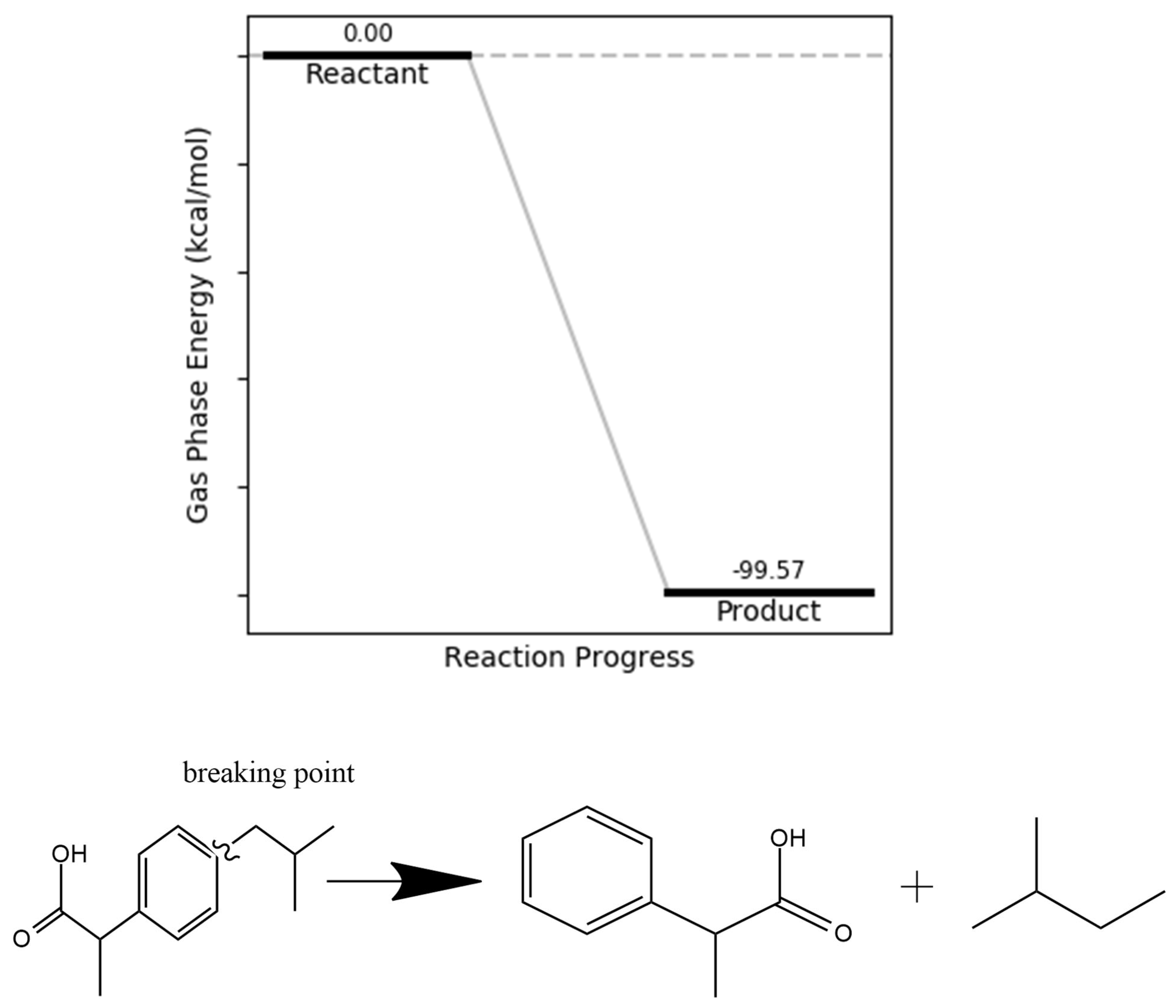

The bond dissociation energy (BDE) values for the O14–C12–C11 bond in ibuprofen across different electronic states—ground (111.94 kcal/mol), excited (–0.85 kcal/mol), cationic (141.15 kcal/mol), and anionic (86.60 kcal/mol)—indicate that this bond is particularly susceptible to cleavage under oxidative conditions, especially in the excited and anionic states. The resulting fragments, including an isobutyl group and a 2-phenylpropanoic acid moiety, are relatively stable due to resonance stabilization within the benzene ring. Reaction energetics calculations confirm that the cleavage process is exergonic, with a product energy value of –99.57 kcal/mol, suggesting that the reaction is both thermodynamically favorable and mechanistically plausible (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

O14–C12–C11 bond dissociation energy.

Figure 5.

O14–C12–C11 bond dissociation energy.

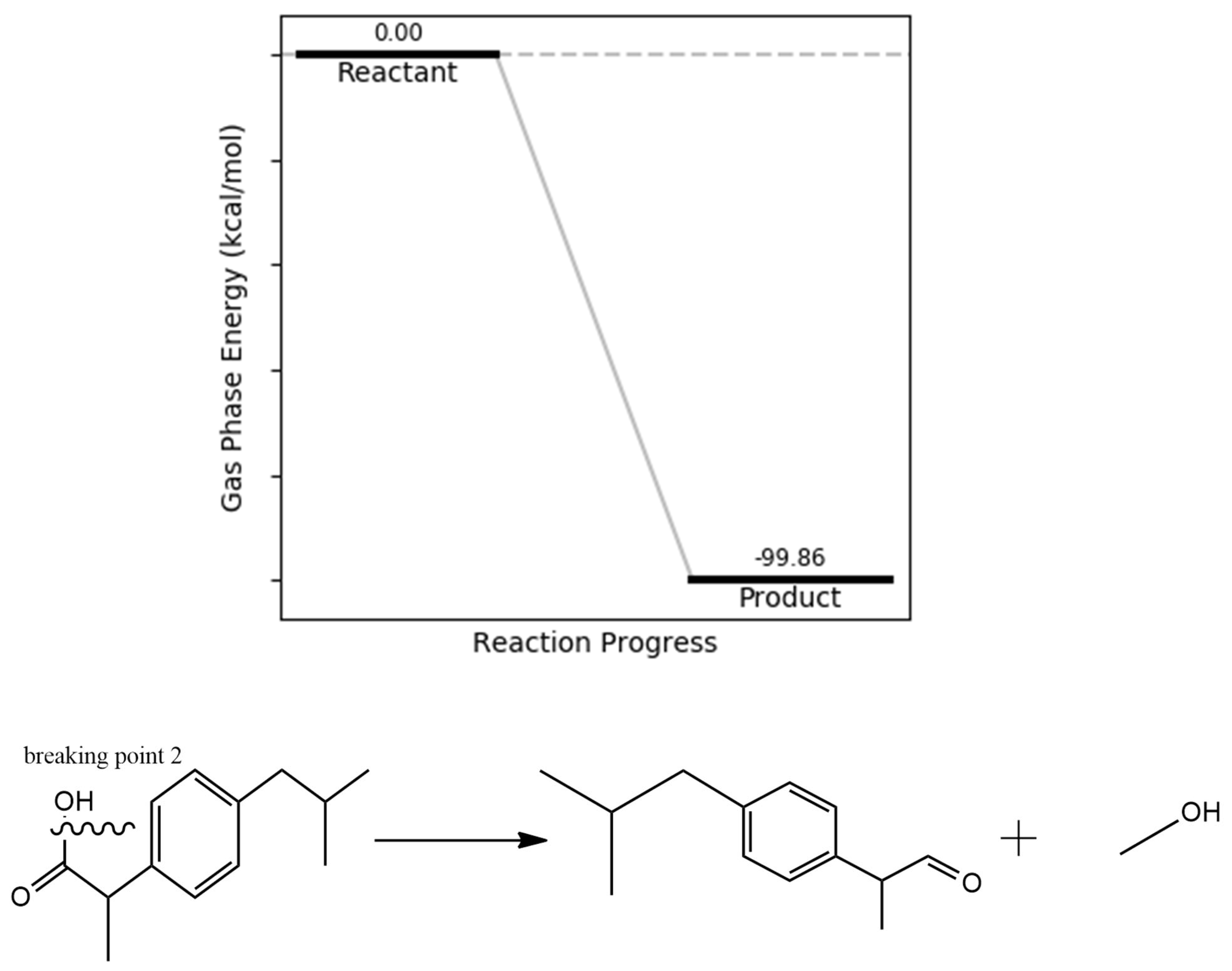

Hydroxyl group removal was identified as another potential cleavage pathway in the ibuprofen degradation mechanism. The bond dissociation energies associated with this pathway were calculated as 112.25 kcal/mol (ground state), –0.27 kcal/mol (excited state), 107.42 kcal/mol (cation), and 43.87 kcal/mol (anion), indicating increased susceptibility under excited and anionic conditions. The resulting fragments are readily oxidizable and correspond with known degradation products previously observed in experimental studies. Additionally, the calculated reaction energetics reveal an exergonic transformation, with a product energy of –99.86 kcal/mol relative to the optimized ibuprofen molecule (

Figure 6), supporting the thermodynamic feasibility of this degradation route.

Figure 6.

OH bond dissociation energy.

Figure 6.

OH bond dissociation energy.

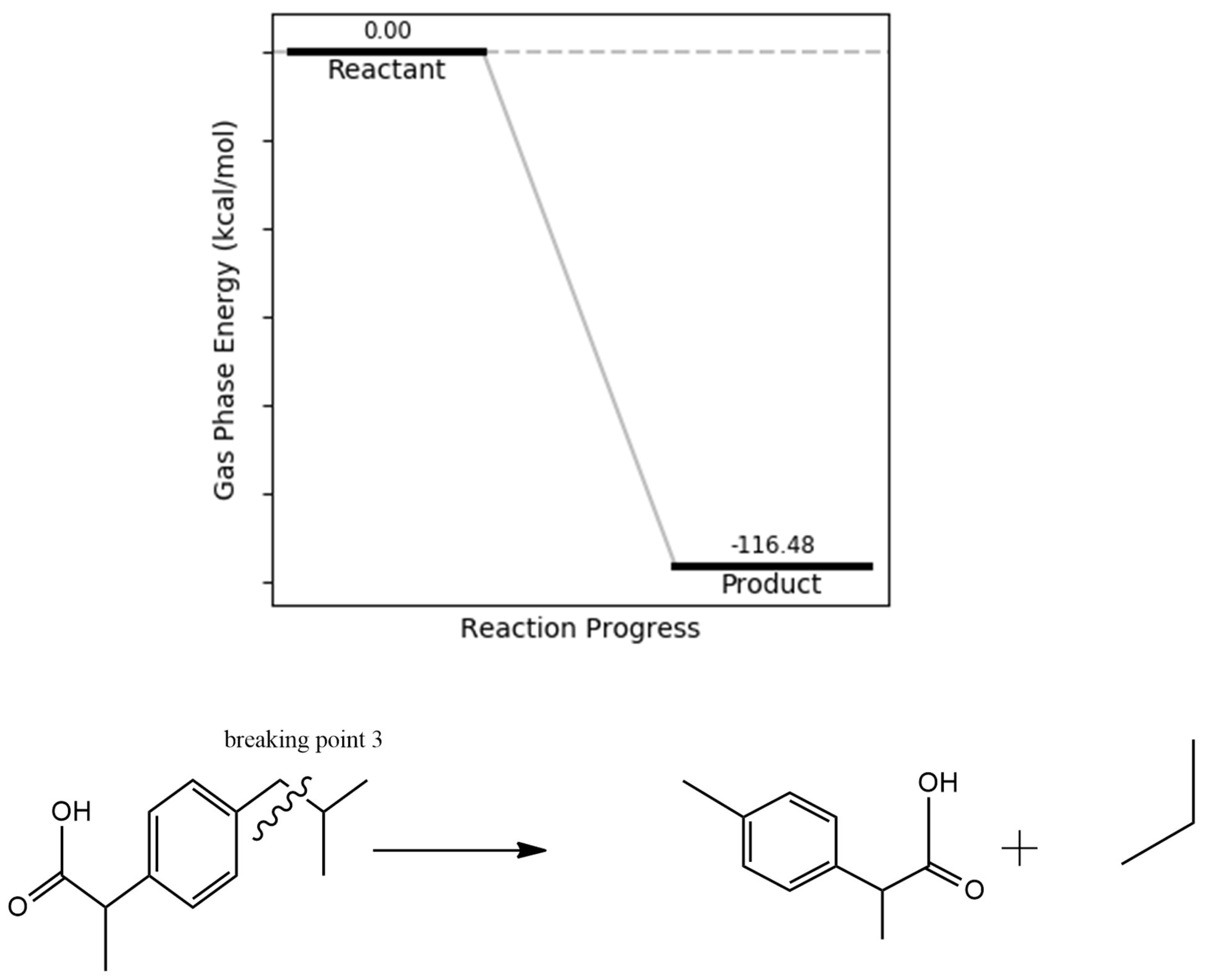

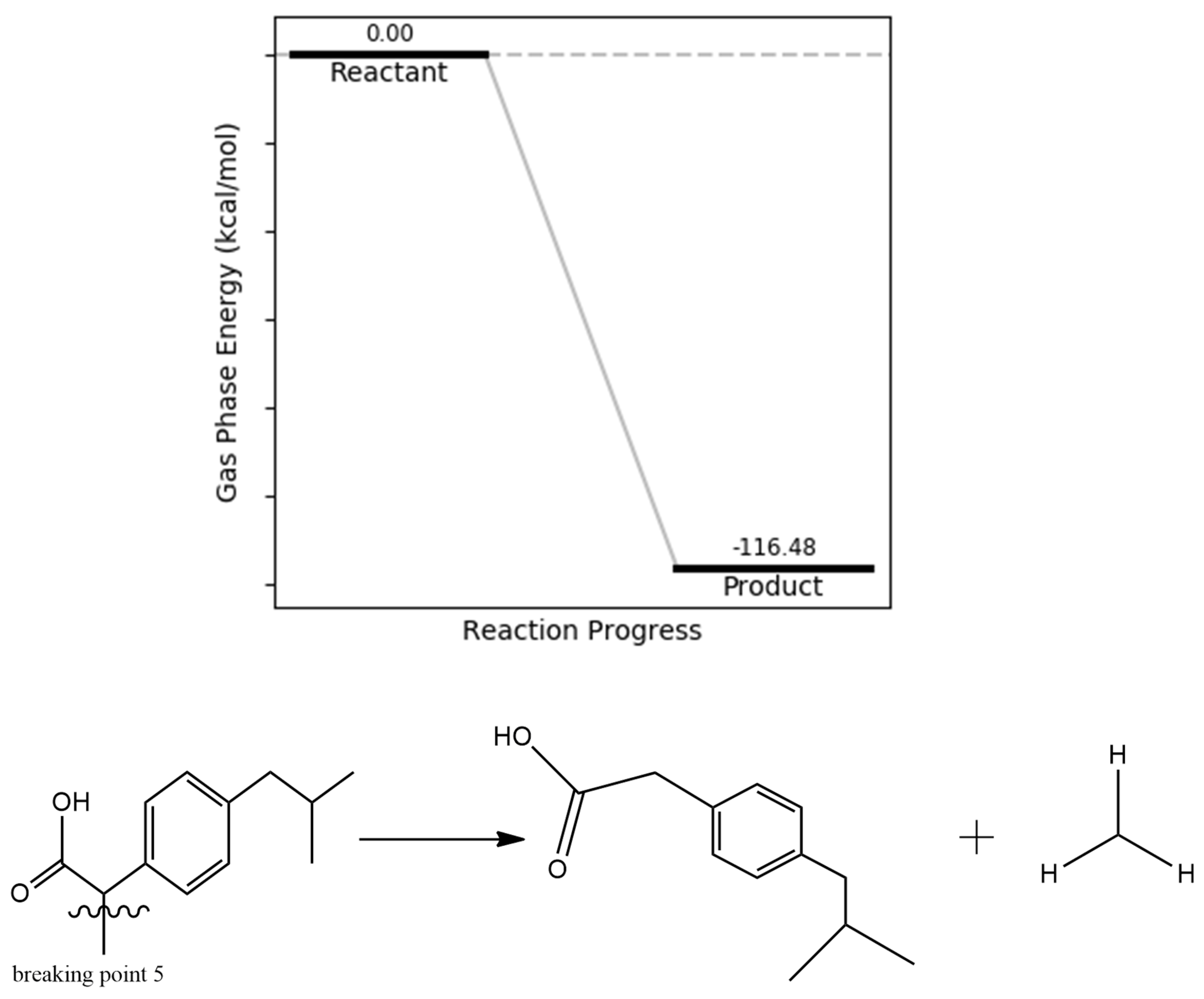

Another proposed degradation pathway involves the cleavage leading to the removal of the CH₃CH₂CH₃ (isopropyl) group (

Figure 7) and its associated side chain. This transformation is energetically favorable, with a calculated product energy of –116.48 kcal/mol. The pronounced thermodynamic favorability is likely attributed to a reduction in strain energy, particularly at the C6–C11–C14–C19 torsional region, as identified in the dihedral angle analysis. The resulting fragments are less sterically hindered and more stable, consistent with degradation products previously detected in experimental studies, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses

Figure 7.

isopropyl bond dissociation energy.

Figure 7.

isopropyl bond dissociation energy.

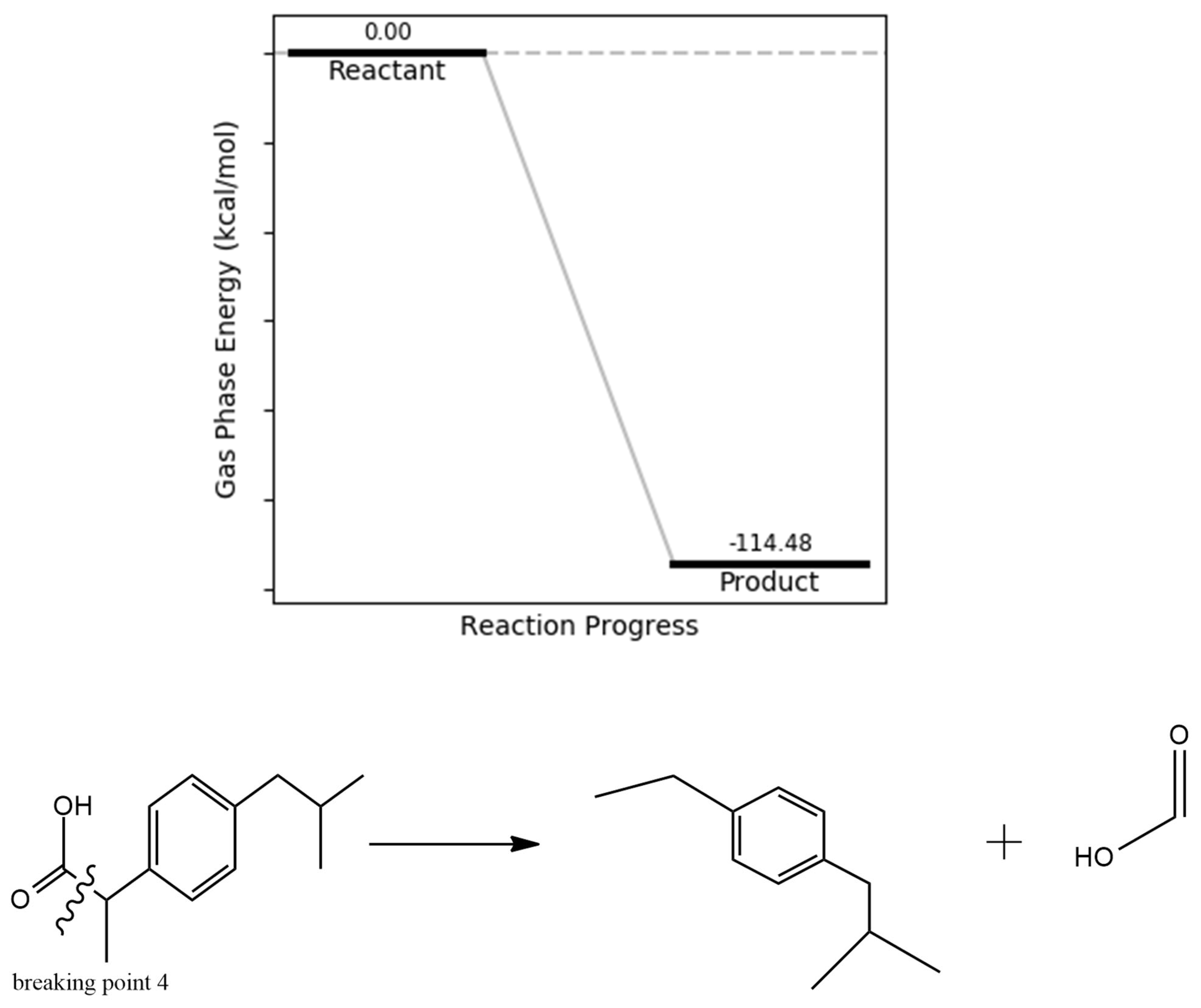

The cleavage of the carboxylic acid group in the ibuprofen degradation pathway is supported by its relatively low bond dissociation energy across all electronic states, with the excited state requiring particularly minimal energy for bond breakage. This highlights the group’s inherent vulnerability to oxidative or photochemical degradation. The reaction energetics further confirm this susceptibility, indicating an exergonic process with a product energy of –114.48 kcal/mol relative to the intact ibuprofen molecule (

Figure 8), reinforcing the thermodynamic plausibility of this degradation route.

Figure 8.

carboxylic acid group bond dissociation energy.

Figure 8.

carboxylic acid group bond dissociation energy.

The removal of the methyl (CH₃) group from ibuprofen is also predicted to be a favorable degradation step, as indicated by low bond dissociation energy values and a product energy of –116.4 kcal/mol from the reaction energetics profile (

Figure 9). This transformation is facilitated by the high electron affinity of the adjacent carboxylic acid (COOH) group, which weakens the bond between the methyl group and the rest of the molecule. Additionally, the resulting fragments are more stable, both energetically and structurally, as evidenced by reduced strain and bond angle deviation at the O14–C12–C11 junction in the optimized geometry.

Figure 9.

O14–C12–C11 bond dissociation energy.

Figure 9.

O14–C12–C11 bond dissociation energy.

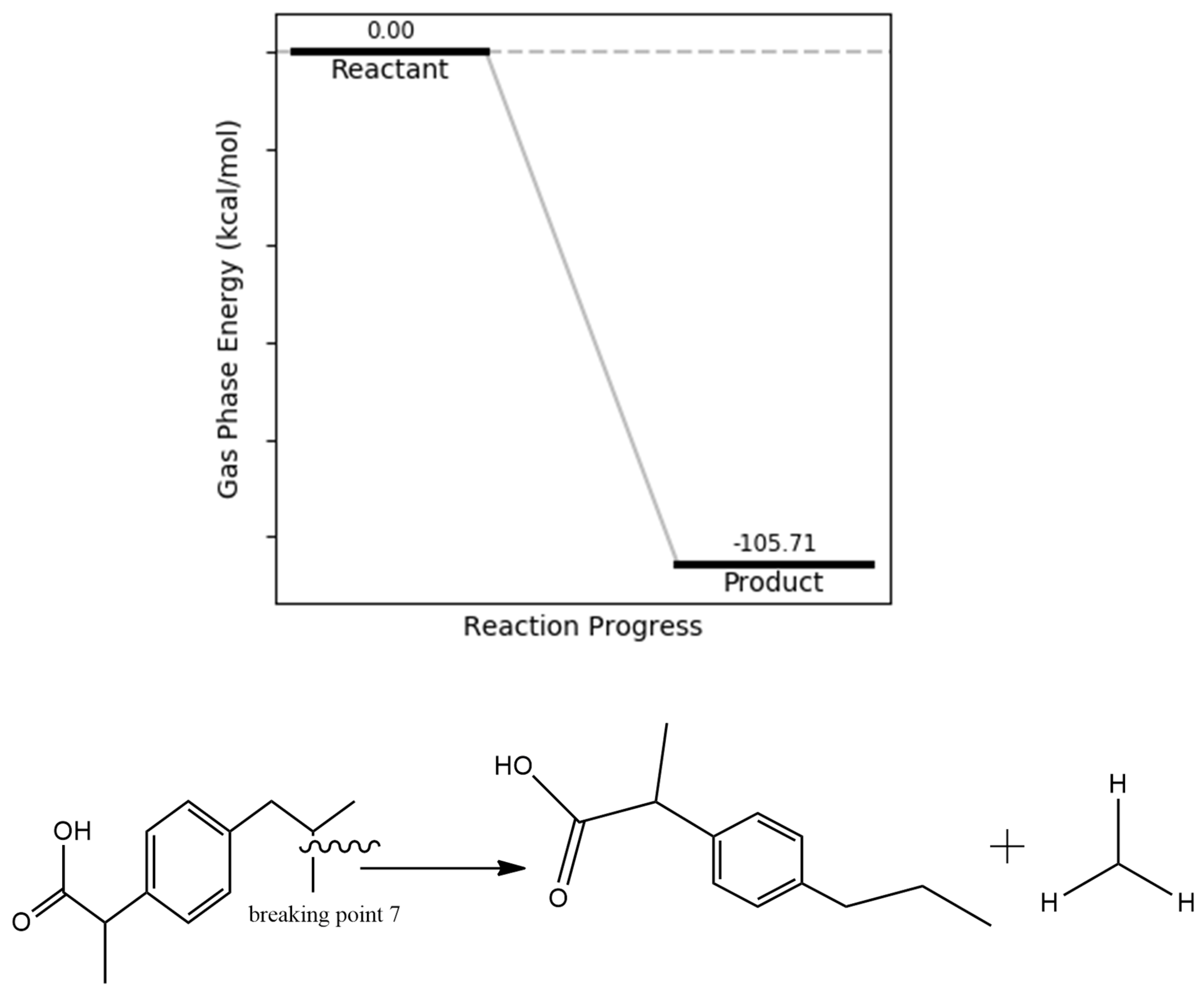

The bond dissociation energy calculations indicate that this particular cleavage requires relatively low energy, likely due to reduced steric hindrance in the resulting products. The reaction energetics further support the feasibility of this degradation step, revealing an exergonic transformation with a product energy of –105.71 kcal/mol relative to the intact ibuprofen molecule (

Figure 10). This suggests that the resulting fragments are both thermodynamically stable and structurally less hindered, favoring spontaneous degradation under oxidative conditions.

Figure 10.

methyl bond dissociation energy.

Figure 10.

methyl bond dissociation energy.

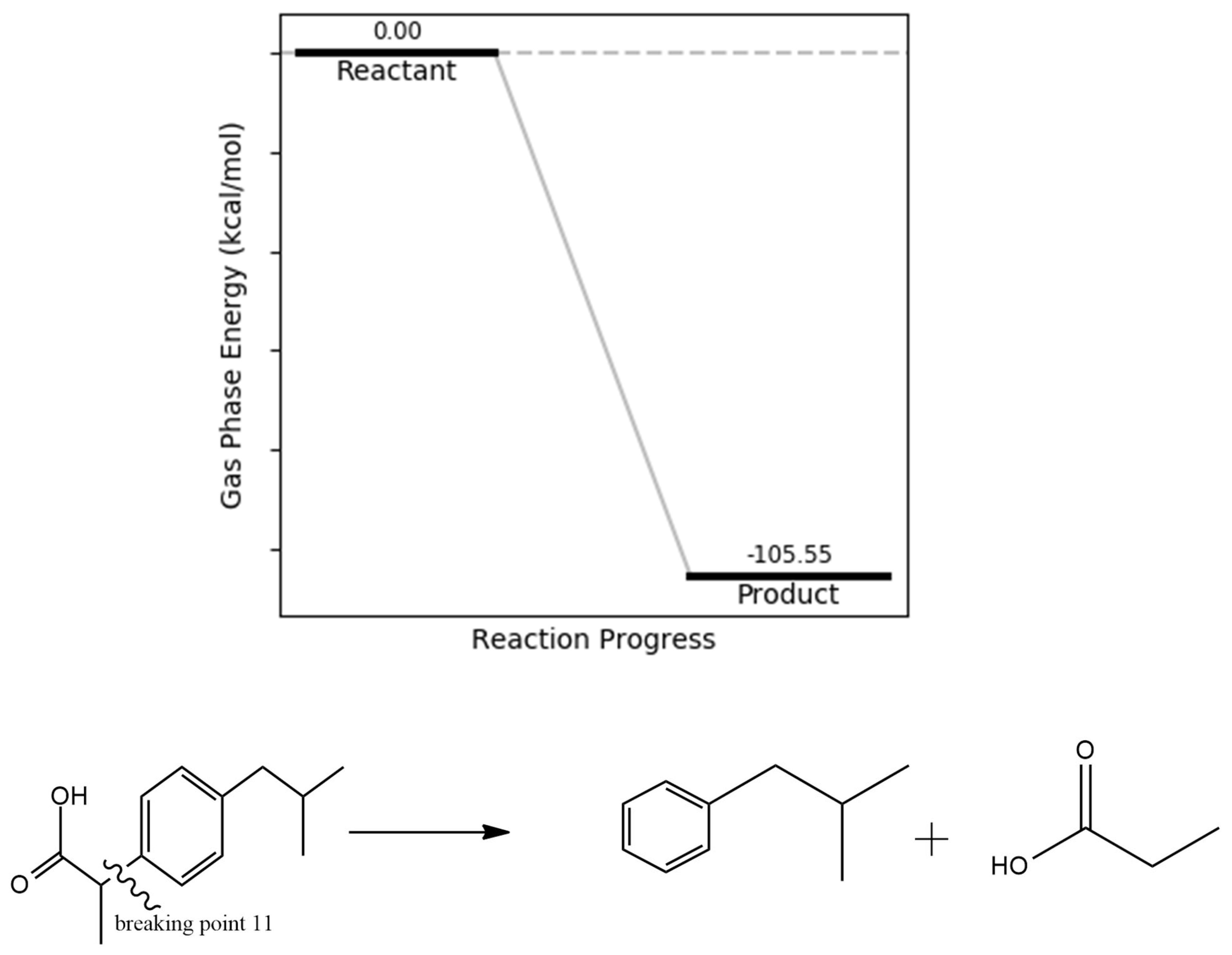

Figure 11.

propionic bond dissociation energy.

Figure 11.

propionic bond dissociation energy.

Cleavage of a specific carbon–carbon bond in the ibuprofen molecule was also identified as energetically favorable based on the bond dissociation energy data. The corresponding reaction energy profile indicates that the resulting fragments possess an energy of –105.55 kcal/mol relative to intact ibuprofen, confirming the feasibility of this degradation step. These fragments exhibit enhanced stability due to electron delocalization within the benzene ring, as supported by electron density maps. Additionally, one of the degradation products, CH₃CH₂COOH (propionic acid), is readily oxidizable into carbon dioxide and water, further supporting its relevance as a plausible oxidative byproduct.

Degradation Mechanism

Figure 12.

Proposed degradation pathway of ibuprofen.

Figure 12.

Proposed degradation pathway of ibuprofen.

3. Materials and Methods

All quantum chemical calculations were performed using the Schrödinger suite Maestro material science (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2023), specifically employing the Jaguar software package (Jaguar, version 12.3, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2023). Density Functional Theory (DFT) was the primary computational method utilized throughout the study.

3.1. Geometry Optimization

The initial three-dimensional structure of ibuprofen was subjected to geometry optimization to obtain its most stable, lowest-energy conformation. This optimization was performed using the B3LYP-D3 functionals combined with the 6-31G** basis set. The B3LYP functional, a hybrid functional that combines Becke’s three-parameter exchange functional with the Lee-Yang-Parr correlation functional, is widely recognized for its accuracy in predicting molecular geometries and energies [

15,

16]. The D3 dispersion correction was included to account for long-range weak interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces), which are crucial for accurate structural predictions in condensed phases and large molecules [

17]. The 6-31G** basis set, a split-valence double-zeta basis set with polarization functions on heavy atoms and hydrogen, provides a good balance between computational cost and accuracy for systems of this size. Convergence criteria for geometry optimization were set to standard values (e.g., force convergence to 0.0001 a.u., energy convergence to 1e-06 a.u.).

3.2. Vibrational Frequency Analysis

Following geometry optimization, vibrational frequency calculations were performed on the optimized structure using the same B3LYP-D3/6-31G** level of theory. This analysis confirmed that the optimized geometry corresponded to a true minimum on the potential energy surface (i.e., no imaginary frequencies), ensuring the stability of the predicted structure. Vibrational frequencies also provide insights into the molecular dynamics and are used for zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) corrections. The B3PW91/6–311++G (2d, 2p) method has been noted as a highly accurate approach for forecasting vibrational spectra [

18,

19], further supporting the robustness of vibrational analysis in this context.

3.3. Electronic Structure and Reactivity Descriptors

Several electronic structure and reactivity descriptors were calculated from the optimized geometry to elucidate the intrinsic reactivity of ibuprofen:

HOMO-LUMO Energy Gap: The energies of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) were calculated. The energy difference, the HOMO-LUMO gap, serves as a crucial indicator of molecular stability and reactivity, particularly its susceptibility to electronic transitions and subsequent chemical transformations [

20]. A smaller gap suggests higher reactivity.

Fukui Functions: These local reactivity descriptors were calculated using the Jaguar software to identify specific atomic sites within the ibuprofen molecule that are prone to nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks. Fukui functions quantify the change in electron density upon the addition or removal of an infinitesimal amount of charge, providing insight into regions of highest electron density (for electrophilic attack) or lowest electron density (for nucleophilic attack) [

5]. The global softness value was also determined from these calculations.

Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE): BDEs were computed for all relevant bonds within the ibuprofen molecule to assess the energetic cost of homolytic bond cleavage. This analysis provides quantitative insights into the intrinsic stability of specific bonds and their susceptibility to oxidative attack. BDE calculations were performed for both the ground and excited states of ibuprofen to understand its reactivity under various conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully employed Density Functional Theory (DFT) to elucidate the oxidative degradation pathways of ibuprofen, offering mechanistic insights beyond those achievable by experimental methods alone. Through comprehensive quantum chemical calculations—including geometry optimization, HOMO–LUMO analysis, Fukui function evaluation, and bond dissociation energy (BDE) assessments—key reactive sites and structurally vulnerable bonds within the ibuprofen molecule were identified with high precision. The calculated narrow HOMO–LUMO energy gap confirmed ibuprofen’s susceptibility to electronic excitation and photodegradation, while the O14–C12–C11 bond and carboxylic acid group emerged as primary sites for oxidative attack. The proposed degradation mechanism presents a detailed, molecular-level framework consistent with previously reported experimental observations.

The findings of this work have important implications for pharmaceutical formulation and quality assurance. By pinpointing the most degradation-prone regions of the ibuprofen molecule, this research provides a predictive basis for developing strategies to enhance drug stability. These may include the use of targeted antioxidants, protective excipients, or structural modifications designed to reduce oxidative susceptibility. Overall, this theoretical contribution supports the design of more robust ibuprofen-based formulations, ultimately ensuring improved shelf-life, efficacy, and patient safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ignatious Satuku. and Amos Misi; methodology, Ignatious Satuku; software, Roy Bisenti; validation, Amos Misi., and Paul Mushonga; formal analysis, Roy Bisenti; investigation, Ignatious Satuku; resources, Amos Misi.; data curation, Amos Misi.; writing—original draft preparation, Ignatious Satuku and Amos Misi.; writing—review and editing, Roy Bisenti and Paul Mushonga.; visualization, Igantious Satuku and Roy Bisenti.; supervision, Amos Misi.; project administration, Paul Mushonga. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [Material Science, Schrodinger suite 2023-1] for the purposes of [HOMO-LUMO analysis for degradation mechanism using Density Functional Theory]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HOMO |

Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital |

| LUMO |

Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| BDE |

Bond Dissociation Energy |

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory |

References

- Madhavi K, Devi BK. Synthetic Strategies for the Development of Ibuprofen Derivatives: A Classified Study. Curr Top Med Chem. 2025;25. [CrossRef]

- Ellepola N, Ogas T, Turner DN, Gurung R, Maldonado-Torres S, Tello-Aburto R, et al. A toxicological study on photo-degradation products of environmental ibuprofen: Ecological and human health implications. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;188:109892. [CrossRef]

- Jan-Roblero J, Cruz-Maya JA. Ibuprofen: Toxicology and Biodegradation of an Emerging Contaminant. Molecules. 2023;28(5):2097. [CrossRef]

- Jahani M, Sedigheh B, Akaberi M, Rajabi O, Farzin Hadizadeh. Recent Progresses in Analytical Perspectives of Degradation Studies and Impurity Profiling in Pharmaceutical Developments: An Updated Review. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2022;53(5):1094–115. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Bu L, Wu Y, Ma W, Zhu S, Zhou S. Mechanistic insight into the degradation of ibuprofen in UV/H2O2 process via a combined experimental and DFT study. Chemosphere. 2020;267:128883. [CrossRef]

- Xiao R, Noerpel M, Luk HL, Wei Z, Spinney R. Thermodynamic and kinetic study of ibuprofen with hydroxyl radical: A density functional theory approach. Int J Quantum Chem. 2013;114(1):74–83. [CrossRef]

- Hassan HA, Ahmed HS, Hassan DF. Free radicals and oxidative stress: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets: Review article. Hum Antibodies. 2024;1–17.

- Vione D, Maddigapu PR, De Laurentiis E, Minella M, Pazzi M, Maurino V, et al. Modelling the photochemical fate of ibuprofen in surface waters. Water Res. 2011;45(20):6725–36. [CrossRef]

- Hu W, Chen M. Editorial: Advances in Density Functional Theory and Beyond for Computational Chemistry. Front Chem. 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Koch D, Pavanello M, Shao X, Ihara M, Ayers PW, Matta CF, et al. The Analysis of Electron Densities: From Basics to Emergent Applications. Chem Rev. 2024;124(22):12661–737. [CrossRef]

- Guan H, Sun H, Zhao X. Application of Density Functional Theory to Molecular Engineering of Pharmaceutical Formulations. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(7):3262–3262. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek A, Łukasz Szeleszczuk, Dariusz Maciej Pisklak. Periodic DFT Calculations—Review of Applications in the Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2020;12(5):415–415. [CrossRef]

- Aiyeshah Alhodaib, Mousa HA, Handal HT, Galal HR, Hala, Elsayed BA, et al. Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems. Nanotechnol Rev. 2025;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra S, Snow D, Shea P, Gálvez-Rodríguez A, Kumar M, Padhye LP, et al. Photodegradation of a mixture of five pharmaceuticals commonly found in wastewater: Experimental and computational analysis. 2022;216:114659–114659. [CrossRef]

- Madanakrishna Katari. Formation and Characterization of Reduced Metal Complexes in the Gas Phase. Hal.science [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Jan 1]; Available from: https://pastel.hal.science/tel-01494829/.

- Wood J. Proquest.com. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Advancements in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Application in Natural Products and Pharmaceutical Chemistry - ProQuest. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/openview/da0d4b0ef2d61b362832a561c3f75b80/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Caldeweyher E, Bannwarth C, Grimme S. Extension of the D3 dispersion coefficient model. J Chem Phys. 2017;147(3):034112. [CrossRef]

- Wang F. Future of computational molecular spectroscopy—from supporting interpretation to leading the innovation. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2023;25(10):7090–105. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki Y, Beć KB, Yusuke Morisawa, Yamamoto S, Tanabe I, Huck CW, et al. Advances, challenges and perspectives of quantum chemical approaches in molecular spectroscopy of the condensed phase. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(19):10917–54. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Rong C, Zhang R, Liu S. Evaluating frontier orbital energy and HOMO/LUMO gap with descriptors from density functional reactivity theory. J Mol Model. 2016;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Dudziak S, Fiszka Borzyszkowska A, Zielińska-Jurek A. Photocatalytic degradation and pollutant-oriented structure-activity analysis of carbamazepine, ibuprofen and acetaminophen over faceted TiO2. J Environ Chem Eng. 2023;11(2):109553. [CrossRef]

- El, Lahoucine Bahsis, Lekbira El Mersly, Anane H, Lebarillier S, Piram A, et al. Insights in the Aqueous and Adsorbed Photocatalytic Degradation of Carbamazepine by a Biosourced Composite: Kinetics, Mechanisms and DFT Calculations. Int J Environ Res. 2021;15(1):135–47. [CrossRef]

- Sevvanthi S, Muthu S, Raja M, Aayisha S, Janani S. PES, molecular structure, spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman), electronic (UV-Vis, HOMO-LUMO), quantum chemical and biological (docking) studies on a potent membrane permeable inhibitor: dibenzoxepine derivative. Heliyon. 2020;6(8):e04724. [CrossRef]

- Zamora PP, Bieger K, Cuchillo A, Tello A, Muena JP. Theoretical determination of a reaction intermediate: Fukui function analysis, dual reactivity descriptor and activation energy. J Mol Struct. 2020;129369. [CrossRef]

- Barrera NF, Javiera Cabezas-Escares, Muñoz F, Muriel WA, Gómez T, Calatayud M, et al. Fukui Function and Fukui Potential for Solid-State Chemistry: Application to Surface Reactivity. J Chem Theory Comput. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Sandyanto Adityosulindro. Activation of homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton processes by ultrasound and ultraviolet/visible irradiations for the removal of ibuprofen in water. Hal.science [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Jan 1]; Available from: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04221776/.

- Guengerich FP, Yoshimoto FK. Formation and Cleavage of C–C Bonds by Enzymatic Oxidation–Reduction Reactions. Chem Rev. 2018;118(14):6573–655.

- Yang J, Zhang BT, Tian L, Die Q, Wang F, Fu H, et al. Free radical formation via BDE-209 thermolysis in the precalciner of a cement kiln: Simulation and DFT study. Sci Total Environ. 2023;905:167145. [CrossRef]

- Ding Z, Zhang J, Fang T, Zhou G, Tang X, Wang Y, et al. New insights into the degradation mechanism of ibuprofen in the UV/H2O2 process: role of natural dissolved matter in hydrogen transfer reactions. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2023;25(44):30687–96. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Bond length of experimental, non-optimised and optimised geometry of ibuprofen.

Table 1.

Bond length of experimental, non-optimised and optimised geometry of ibuprofen.

| Bond |

Experimental

|

Calculated before geometry Optimisation |

Calculated after geometry Optimisation |

| C12–O13 |

1.306 |

1.356 |

1.35 |

| C12–O14 |

1.204 |

1.211 |

1.23 |

| C12–C11 |

1.503 |

1.526 |

1.54 |

| C11–C6 |

1.500 |

1.535 |

1.53 |

| C11–C15 |

1.525 |

1.530 |

1.55 |

| C6 –C5 |

1.374 |

1.401 |

1.40 |

| C6 –C1 |

1.376 |

1.393 |

1.40 |

| C1 –C2 |

1.392 |

1.402 |

1.39 |

| C5 –C4 |

1.380 |

1.400 |

1.39 |

| C2 –C3 |

1.396 |

1.395 |

1.40 |

| C3 –C7 |

1.493 |

1.514 |

1.52 |

| C7–C8 |

1.529 |

1.550 |

1.55 |

| C8–C9 |

1.508 |

1.535 |

1.54 |

| C8–C10 |

1.519 |

1.534 |

1.54 |

| O30–H13 |

0.963 |

0.976 |

0.96 |

Table 2.

Bond angles of the experimental, non-optimised and after geometry optimisation.

Table 2.

Bond angles of the experimental, non-optimised and after geometry optimisation.

| Bond Angle |

Experimental Bond Angle |

Bond Angle before geometry Optimisation |

Bond Angle after geometry Optimisation |

| O13–C12–O14 |

123.4 |

122.5 |

122.6 |

| O11–C12–C13 |

115.4 |

111.8 |

112.8 |

| O14–C12–C11 |

121.1 |

125.7 |

124.6 |

| C12–C11–C15 |

111.7 |

110.2 |

112.8 |

| C30–C24–C3 |

106.7 |

109.5 |

111.2 |

| C26–C24–C3 |

114.4 |

117.2 |

120.1 |

| C24–C3–C4 |

120.9 |

120.2 |

120.4 |

| C2 –C3 –C24 |

120.9 |

121.3 |

121.1 |

| C5 –C6 –C11 |

120.2 |

120.4 |

120.1 |

| C1 –C6 –C11 |

121.8 |

121.7 |

120.4 |

| C6 –C11–C14 |

113.9 |

114.4 |

113.2 |

| C11–C14–C15 |

110.1 |

110.6 |

110.8 |

| C11–C14–C19 |

111.5 |

112.0 |

111.3 |

| C15–C14–C19 |

111.5 |

111.0 |

112.6 |

Table 3.

Dihedral angle of the experimental, non-optimised and optimised geometry of ibuprofen.

Table 3.

Dihedral angle of the experimental, non-optimised and optimised geometry of ibuprofen.

| Torsional/Dihedral angle |

Experimental Torsional Angle/ |

Torsional Angle before geometry optimisation |

Torsional Angle after geometry optimisation |

| O14–C12–C11–C6 |

-89.6 |

-95.5 |

-90.1 |

| O13–C12–C11–C6 |

88.7 |

83.0 |

88.6 |

| H30–O13–C12–O14 |

-3.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

| H30–O13–C12–C11 |

-175.1 |

-176.6 |

-177.4 |

| O14–C12–C11–C15 |

36.0 |

30.2 |

35.4 |

| C1 –C6 –C11–C14 |

-177.7 |

178.DY5 |

-141.0 |

| C6 –C11–C14–C19 |

168.5 |

171.7 |

177.1 |

| C6 –C11–C14–H20 |

50.4 |

54.3 |

60.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).