1. Introduction

For divers operating in cold, high-pressure underwater environments, maintaining body temperature is not just a matter of comfort it’s critical for survival. Prolonged immersion in frigid waters leads to accelerated core heat loss, risking hypothermia, fatigue, and cognitive impairment. Traditional diving suits, typically made from neoprene or other insulators, struggle to maintain effectiveness at depth due to hydrostatic compression, which reduces their thickness and thermal resistance. It’s as if the ocean itself is giving divers an uninvited, icy hug.

Recent advances in materials science have identified phase change materials (PCMs) as promising additives for enhancing thermal protection. PCMs absorb or release latent heat at specific transition temperatures, creating a thermal buffering effect that helps maintain stable temperatures near the skin. When integrated into diving suits, these materials can extend operational endurance and improve safety. However, making this work in the real world is far from trivial.

While previous research has explored PCM integration and pressure effects separately, few models have captured the nonlinear, coupled nature of these phenomena under realistic underwater conditions. Most existing models oversimplify by ignoring the changes in thermal conductivity due to pressure or by treating phase change effects in isolation. In other words, they don’t fully consider what happens when a diver is both squished by the ocean and relying on fancy materials to stay warm.

This study aims to bridge this gap by developing a comprehensive one-dimensional, multi-layer thermal model that explicitly includes:

Hydrostatic pressure–dependent reductions in thermal conductivity,

Internal metabolic heat generation with depth-varying attenuation,

Detailed latent heat buffering via an explicit phase-change front-tracking method.

This modeling approach provides a more physically realistic simulation of heat transfer in diving suits under cold, high-pressure conditions. Ultimately, it offers valuable guidance for the design of next-generation, pressure-aware, PCM-enhanced thermal protection systems tailored for professional divers, rescue teams, and marine researchers braving the cold embrace of the deep sea

2. Background Studies

Recent advances in wearable thermal regulation systems have highlighted the potential of phase change materials (PCMs) in enhancing the performance of cold-environment protective gear such as diving suits. Wei et al. [

1] conducted a numerical analysis on PCM-enhanced suits, demonstrating that optimized PCM properties significantly improve thermal insulation, particularly under cold-water immersion. Earlier empirical studies by West [

2] examined the thermal conductivity of various wetsuit materials, revealing that compressibility and fabric type substantially affect heat retention.

A foundational review by Dutil et al. [

3] explored mathematical modeling of PCMs, emphasizing simulation as a critical tool for predicting latent heat behavior. Similarly, Verma et al. [

4] compared transient modeling techniques for latent heat thermal storage systems and highlighted the importance of accurate phase transition tracking. More recent work by Mandal [

5] surveyed PCM stabilization methods and proposed frameworks to maintain thermal performance under mechanical and environmental stress.

To model complex PCM behavior, Liu et al. [

6] introduced a multiscale simulation approach using physics-informed neural networks to estimate the effective thermal conductivity of PCM composites, demonstrating the growing role of data-driven methods in material design. Meanwhile, He et al. [

7] implemented the lattice Boltzmann method to simulate phase change in porous structures, achieving high accuracy and resolution of microscale interactions.

While Aghoei et al. [

8] focused on PCMs in building envelopes, their insights into passive thermal stabilization are relevant to body-worn insulation systems. Similarly, MANSUETI and GIANOLI [

9] modeled transient PCM behavior for energy storage systems, offering valuable techniques for simulating heat retention in wearable applications. Attinger et al. [

10] further reviewed surface engineering strategies to enhance phase-change heat transfer, which may improve thermal interactions at PCM-textile interfaces.

Collectively, these studies establish the scientific groundwork for this paper’s modeling framework, which integrates PCM buffering, internal metabolic heat generation, and pressure-dependent thermal diffusivity to improve diving suit performance in extreme marine environments.

Recent research in bio-thermal transport also informs this study. Notably, Alzubadi and Others [

11] developed a micropolar nanofluid model to simulate thermally and magnetically driven flow in a ciliated asymmetric microchannel—representing fluid motion in the male reproductive tract. Solved numerically using MATLAB’s

bvp4c solver, the model incorporated Brownian motion, thermophoresis, and micro-rotation, capturing complex heat–momentum coupling in a non-Newtonian regime.

Although this work is microscale in scope, it shares key methodological features with our approach, particularly the modeling of spatially varying thermal properties and the use of boundary-driven internal source terms. These parallels support the adaptation of advanced physiological modeling techniques for marine wearable applications in harsh environments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mathematical Framework

This study presents a one-dimensional transient heat transfer model for a multi-layered cold-water diving suit incorporating phase change materials (PCMs), subjected to hydrostatic pressure. The model integrates internal metabolic heat generation, pressure-dependent thermal properties, and the latent heat buffering effect of PCM.

3.1.1. Governing Equation

The temperature distribution

is governed by:

where

is the pressure-dependent thermal diffusivity,

is metabolic heat generation, and

models latent heat effects from PCM.

3.1.2. Pressure Dependence

Hydrostatic pressure and its effect on thermophysical properties are modeled as:

3.1.3. Metabolic Heat Generation

Metabolic heat is modeled as an exponentially decaying source:

3.1.4. Latent Heat Buffering

Latent heat effects near the PCM melting point are incorporated using:

3.2. Similarity Transformation

To simplify the model, a similarity variable is introduced:

This transforms the PDE into an ODE:

3.3. Domain and Layers

The suit is modeled as three layers:

Inner Lining: Neoprene-like material

PCM Layer: Paraffin-based with latent heat

Outer Layer: Low-conductivity insulation

Each layer has unique k, , and .

3.4. Stefan Phase Change Model

The PCM layer is treated using a Stefan formulation. Solid (

) and liquid (

) regions obey:

The phase interface satisfies:

3.5. Boundary Conditions

Convective boundary conditions are applied:

3.6. Parameter Overview

Table 1.

Key parameters and variables used in the mathematical model.

Table 1.

Key parameters and variables used in the mathematical model.

| Symbol |

Description |

Units |

| T |

Temperature |

°C |

|

PCM melting temperature |

°C |

|

Transition range width |

°C |

|

Heat generation coefficient |

W/m3

|

|

Latent heat |

J/kg |

| k |

Thermal conductivity |

W/m · K |

|

Conductivity at ambient |

W/m · K |

|

Conductivity sensitivity |

1/Pa |

|

Specific heat |

J/kg · K |

|

Density |

kg/m3

|

|

Water density |

kg/m3

|

| g |

Gravity |

m/s2

|

| x |

Depth coordinate |

m |

|

Similarity variable |

dimensionless |

|

Thermal diffusivity |

m2/s |

| t |

Time |

s |

3.6.1. Interplay with Phase Change Buffering

The pressure-induced changes in thermal properties interact with the phase change buffering effect of the PCM layer. Reduced conductivity at depth prolongs the thermal plateau around the PCM melting temperature, supporting better thermal regulation over time.

Incorporating pressure-dependent thermal properties is a critical aspect of the model. It captures the realistic compression and insulation effects experienced by diving suits under high-pressure underwater conditions. This significantly influences overall heat transfer behavior and the level of thermal protection provided, underscoring the importance of accounting for depth-dependent material properties in the design of advanced protective equipment for extreme environments.

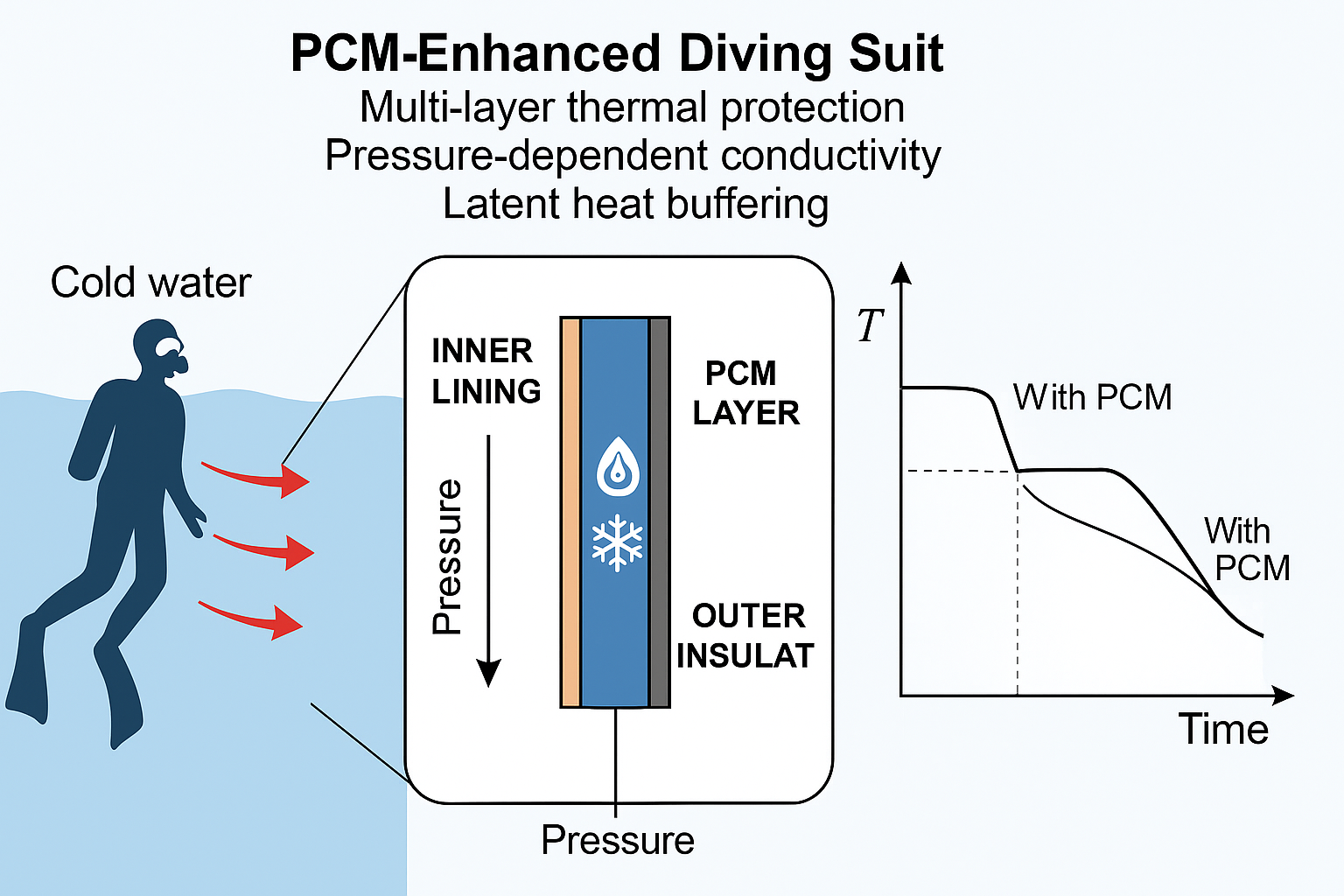

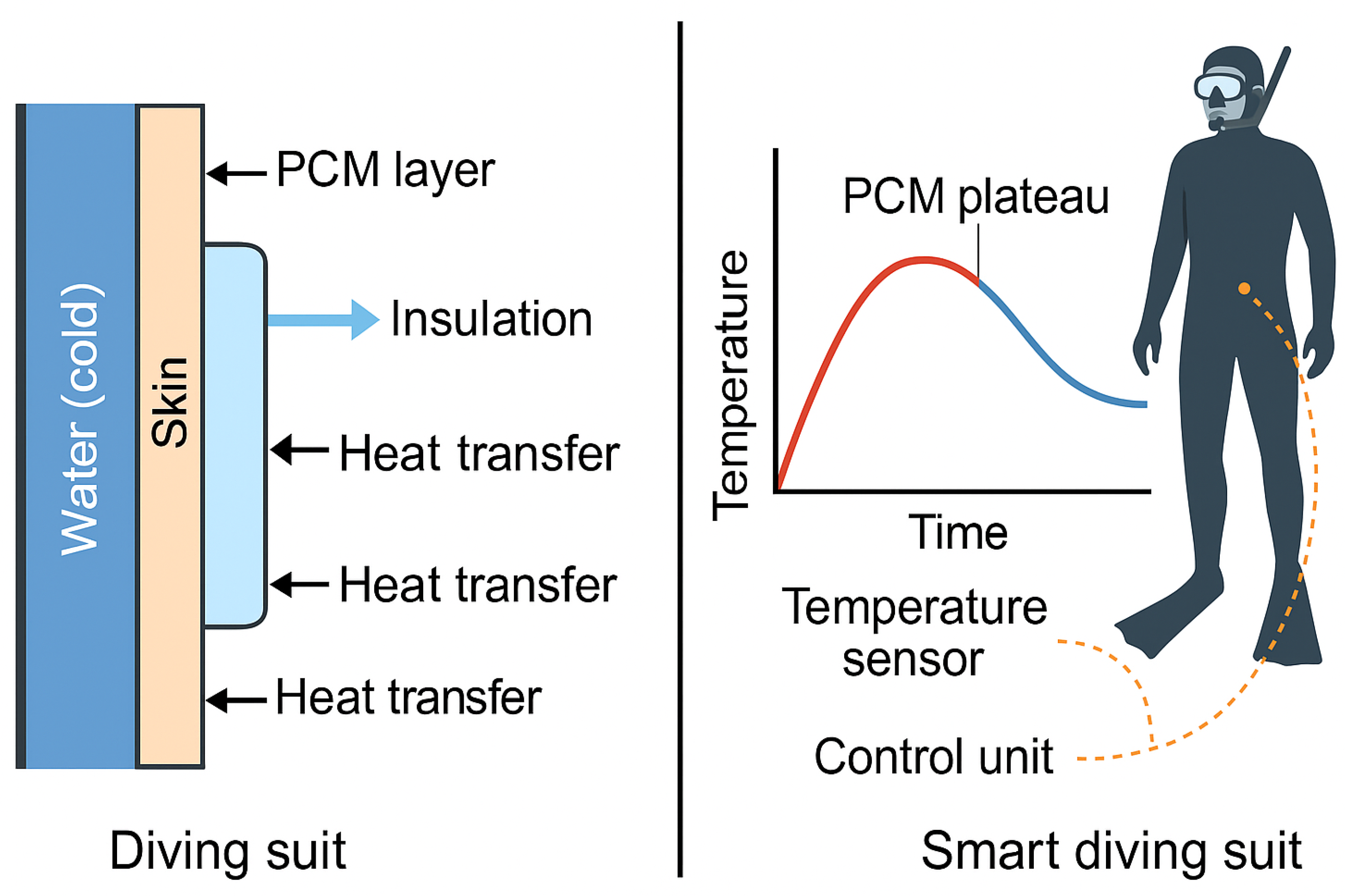

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual structure of the diving suit model, highlighting the thermal pathways and location of the PCM layer, which plays a key role in buffering temperature near the body. The hydrostatic pressure gradient compresses the suit progressively with depth, which is modeled as a depth-dependent reduction in thermal diffusivity.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the diving suit cross-section showing layered structure with internal body heat source, embedded phase change material (PCM) zone near the skin, and exposure to cold water at the outer surface. The pressure gradient increases with depth, compressing suit layers and altering thermal conductivity.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the diving suit cross-section showing layered structure with internal body heat source, embedded phase change material (PCM) zone near the skin, and exposure to cold water at the outer surface. The pressure gradient increases with depth, compressing suit layers and altering thermal conductivity.

3.7. Ethical Approval and AI Usage

This study did not involve human or animal subjects and did not require ethical approval. No generative AI was used for data analysis or scientific content generation. Only minor text editing (grammar, formatting) was assisted by AI tools.

4. Results

This section presents the numerical results obtained from simulating heat transfer in a multi-layer diving suit embedded with Phase Change Material (PCM) under varying hydrostatic pressures. The results are derived from solving the mathematical model described earlier and highlight the interplay between pressure-sensitive thermal conductivity, internal heat generation, and PCM buffering.

4.1. Numerical Simulation and Temperature Evolution

The governing equations were discretized using an explicit finite difference method with enthalpy-based treatment of the phase change interface.

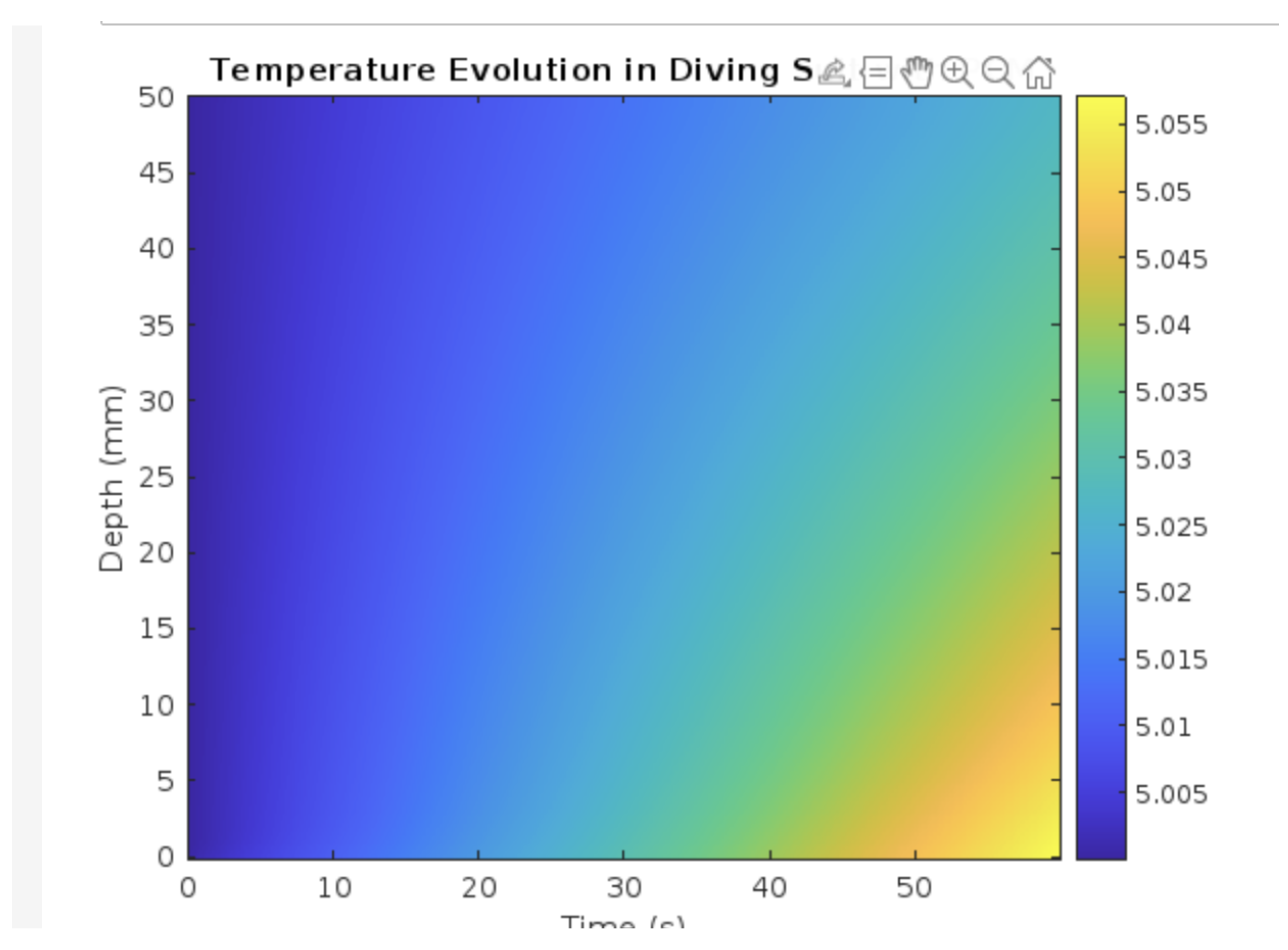

Figure 2 shows the temperature evolution across the diving suit over a 10-minute exposure.

Figure 2.

Simulated temperature evolution across the diving suit. The PCM zone (15–35 mm) shows a thermal plateau around the melting temperature (C), buffering internal heat and reducing thermal gradients.

Figure 2.

Simulated temperature evolution across the diving suit. The PCM zone (15–35 mm) shows a thermal plateau around the melting temperature (C), buffering internal heat and reducing thermal gradients.

The PCM region exhibits a nearly isothermal plateau near , significantly slowing heat loss from the inner body-facing layer to the outer surface in contact with cold water.

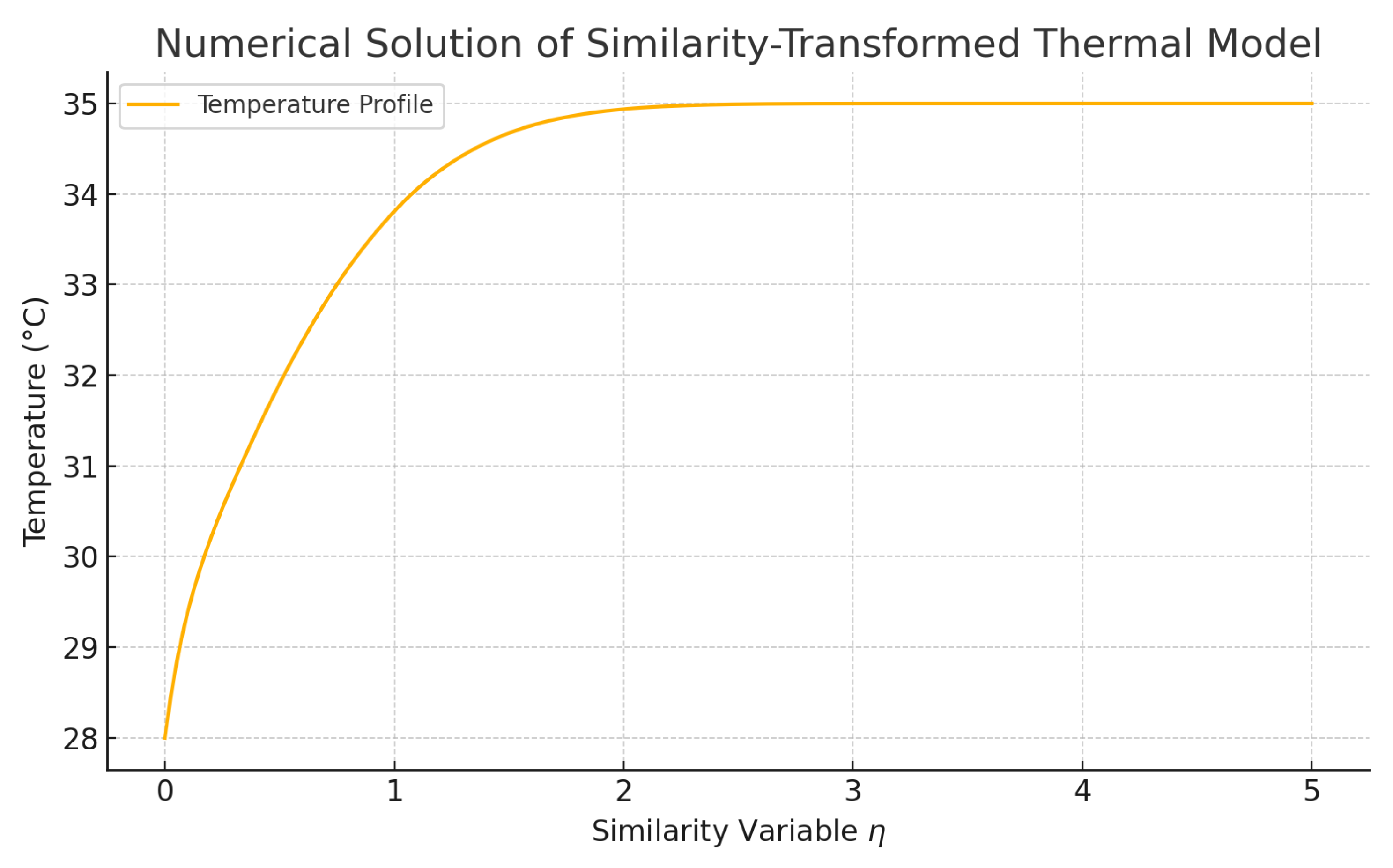

4.2. Similarity Solution

Using a similarity transformation, the heat conduction PDE was reduced to an ODE in the similarity variable

. The resulting dimensionless temperature profile

is presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Similarity-transformed solution of dimensionless temperature showing internal metabolic heating, PCM buffering, and reduced thermal conductivity at depth.

Figure 3.

Similarity-transformed solution of dimensionless temperature showing internal metabolic heating, PCM buffering, and reduced thermal conductivity at depth.

4.3. Time Evolution and Pressure Effects

Figure 4 illustrates how the temperature profile develops over time under pressure-sensitive thermal conductivity.

Figure 4.

Temperature profiles at one-minute intervals for 10 minutes. The PCM layer delays cooling, while hydrostatic pressure reduces outer layer conductivity.

Figure 4.

Temperature profiles at one-minute intervals for 10 minutes. The PCM layer delays cooling, while hydrostatic pressure reduces outer layer conductivity.

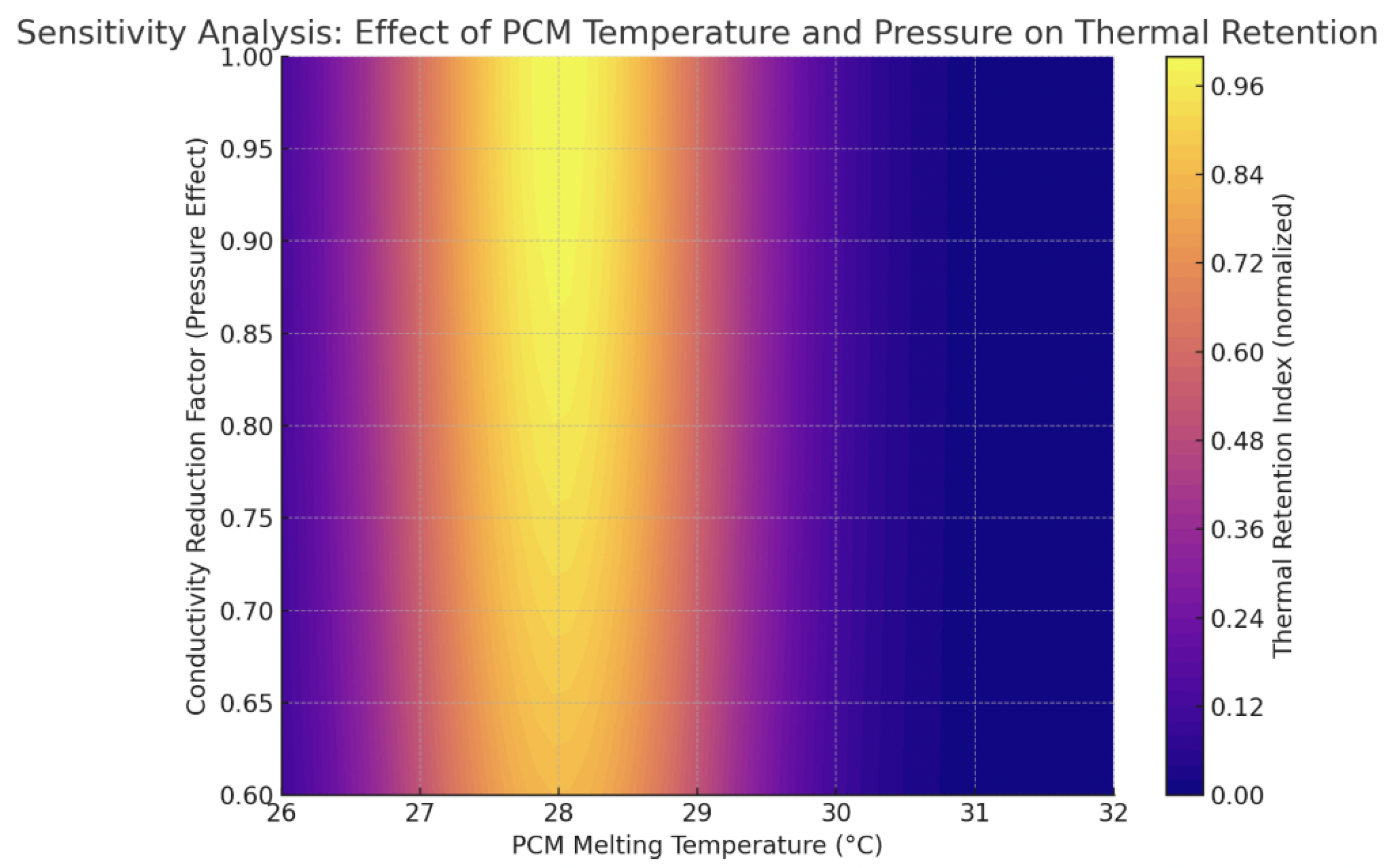

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

A parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Figure 5 displays how changes in PCM melting point and pressure sensitivity affect temperature retention.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity heatmap showing retention dependence on PCM melting point and thermal conductivity reduction factor.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity heatmap showing retention dependence on PCM melting point and thermal conductivity reduction factor.

Key findings:

Higher latent heat improves buffering.

Greater pressure sensitivity increases insulation.

Broader PCM transition ranges stabilize temperature.

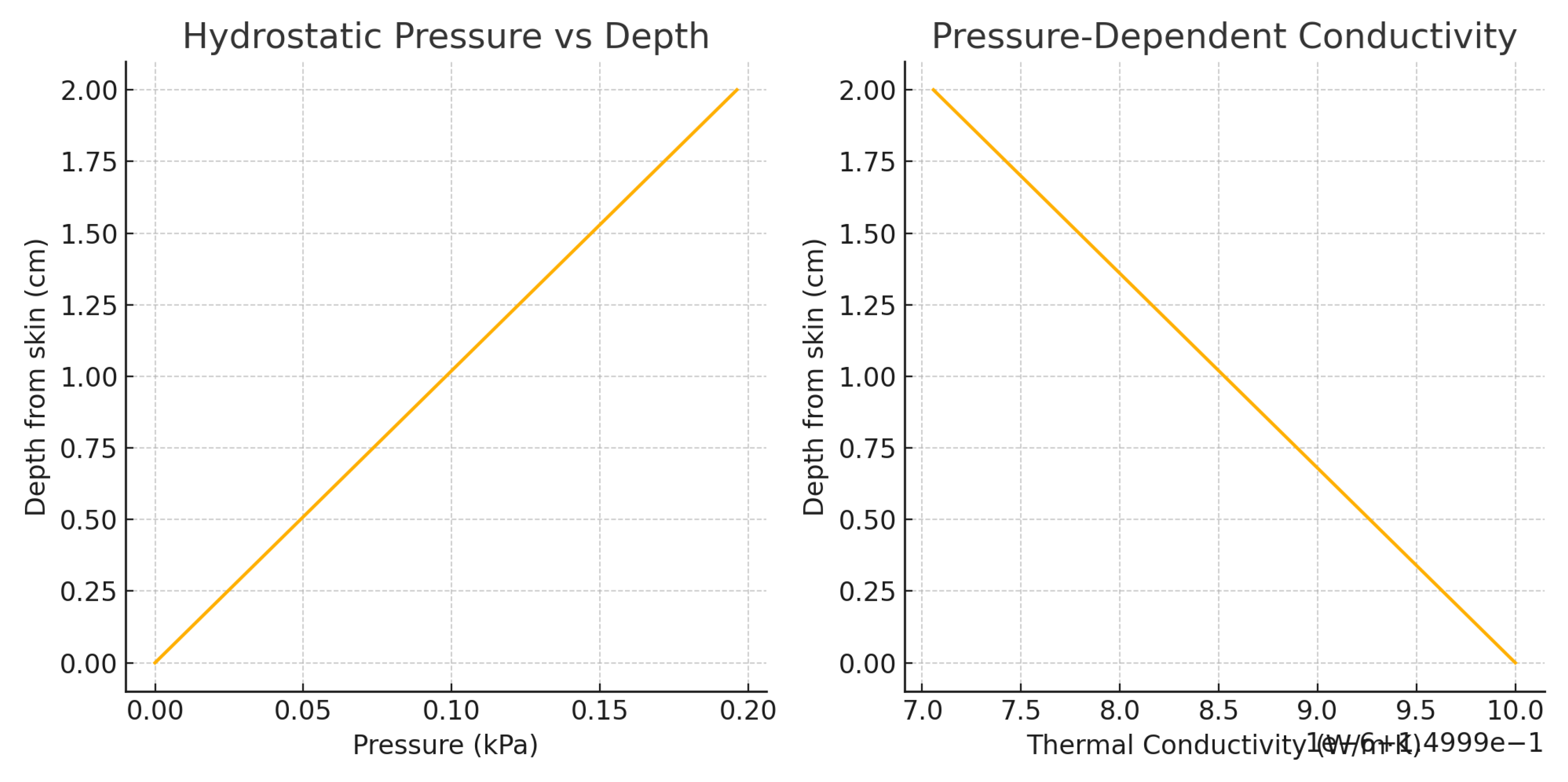

4.5. Hydrostatic Pressure and Thermal Conductivity

Hydrostatic pressure increases linearly with depth and decreases thermal conductivity as shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Left: Hydrostatic pressure profile. Right: Decrease in thermal conductivity due to suit compression.

Figure 6.

Left: Hydrostatic pressure profile. Right: Decrease in thermal conductivity due to suit compression.

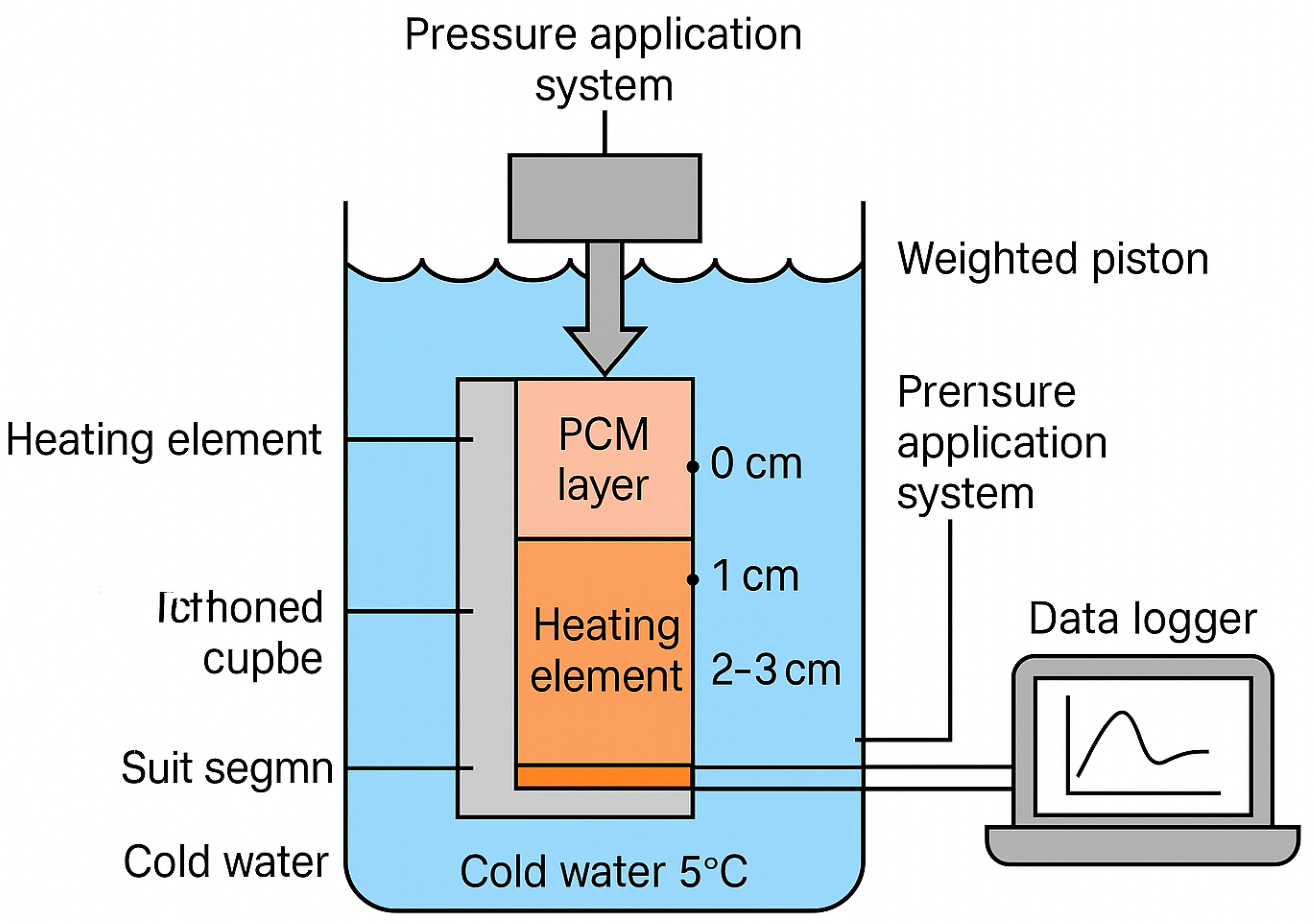

4.6. Experimental Validation Setup

An experimental validation framework is proposed in

Figure 7, including PCM-enhanced samples, pressure application, and temperature monitoring.

Figure 7.

Experimental setup for validating model predictions under simulated cold-water and pressure conditions.

Figure 7.

Experimental setup for validating model predictions under simulated cold-water and pressure conditions.

4.7. Simulation Parameters

Table 2.

Example numerical parameters used in the multi-layer diving suit model

Table 2.

Example numerical parameters used in the multi-layer diving suit model

| Parameter |

Description |

Value |

| L |

Total thickness of suit |

5 cm |

|

Spatial discretization step |

0.5 mm |

|

Time step |

0.1 s |

|

Conductivity (inner lining) |

0.3 W/mK |

|

Conductivity (PCM) |

0.2 W/mK |

|

Conductivity (outer layer) |

0.05 W/mK |

|

Density (all layers) |

800 kg/m3

|

|

Specific heat (all layers) |

2000 J/kgK |

|

Latent heat of PCM |

200 kJ/kg |

|

PCM melting temperature |

28 °C |

|

Convective coefficient (skin side) |

30 W/m2K |

|

Convective coefficient (water side) |

1000 W/m2K |

|

Pressure sensitivity coefficient |

0.0002 1/Pa |

|

Surface metabolic heat generation |

1500 W/m3

|

|

Decay constant for metabolism |

15 1/m |

The results demonstrate the importance of considering PCM buffering and pressure-sensitive conductivity in diving suit design. Future work includes validating the predictions using the proposed experimental framework.

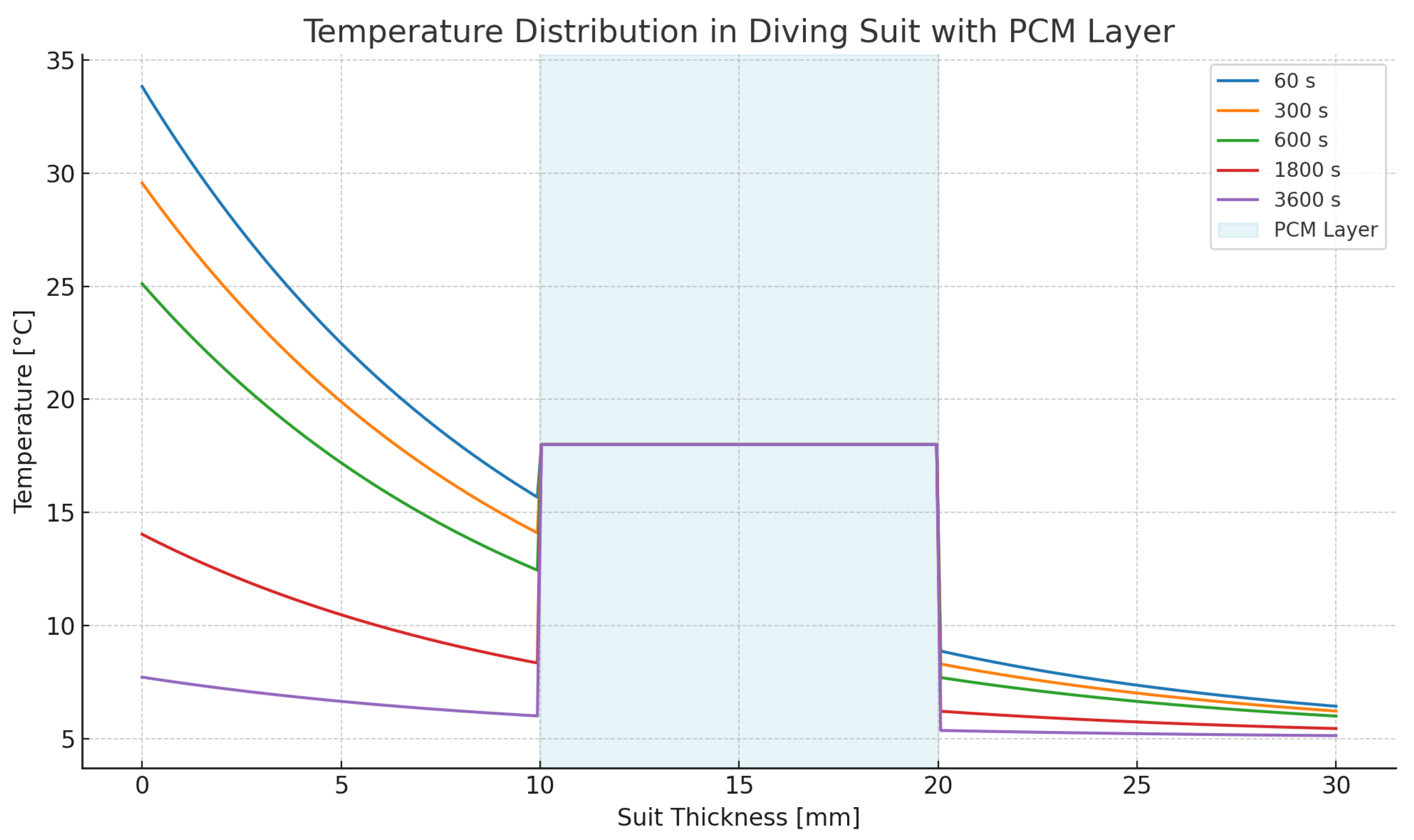

Figure 8 illustrates the transient temperature distribution across a modeled diving suit structure incorporating a paraffin-based phase change material (PCM) layer. The suit is conceptualized as a one-dimensional composite with internal metabolic heat flux and external exposure to cold water. The simulation spans from

s to

s and resolves thermal gradients across the thickness.

Figure 8.

Temperature distribution across the multi-layered diving suit over time, including an embedded PCM layer between mm and mm. The PCM zone maintains a thermal plateau near the phase change temperature (C), demonstrating the thermal buffering effect.

Figure 8.

Temperature distribution across the multi-layered diving suit over time, including an embedded PCM layer between mm and mm. The PCM zone maintains a thermal plateau near the phase change temperature (C), demonstrating the thermal buffering effect.

The PCM layer, located between mm and mm, exhibits a consistent thermal plateau around the phase change temperature (C). This plateau results from latent heat absorption during melting, which delays further temperature change despite ongoing thermal input from the body. At early stages ( s), the presence of this buffering zone significantly reduces the temperature gradient across the suit, improving insulation.

As time progresses, the PCM gradually absorbs heat and approaches full phase transition. At s and beyond, the thermal resistance of the suit decreases, and a continuous gradient forms across the outer insulating layer. By s, the PCM’s thermal storage capacity begins to saturate, resulting in increased heat flux toward the outer interface.

This simulation confirms that incorporating PCM within a layered suit structure can effectively modulate transient heat transfer, enhance thermal comfort, and extend operational endurance in cold aquatic environments. The results also support the potential for optimization of PCM thickness and placement based on mission duration and ambient conditions.

5. Numerical Interpretation and Discussion

The simulations conducted in this study highlight the complex thermal interactions within a multi-layer, PCM-enhanced diving suit operating under high hydrostatic pressure. By explicitly modeling pressure-dependent thermal conductivity, internal metabolic heat generation, and latent heat buffering, the results provide a realistic prediction of suit performance in cold-water, deep-sea environments.

A key finding is the emergence of a pronounced thermal plateau near the PCM melting temperature. This plateau demonstrates the latent heat buffering capacity of the PCM layer, significantly delaying heat loss toward the external cold-water boundary. The simulations confirm that increasing hydrostatic pressure reduces thermal conductivity in the outer layers, thereby enhancing insulation at depth. This dual mechanism—combining latent heat absorption and pressure-induced conductivity reduction—represents a crucial design consideration for advanced thermal protection systems.

To further improve physical realism, the study also explored the application of non-Fourier heat transfer models. The hyperbolic Cattaneo–Vernotte (CV) model introduces a finite propagation speed for thermal signals, producing a smoother, wave-like temperature profile near the skin and at PCM interfaces. This behavior better matches the expected real-time buffering effects of PCMs under rapid transients.

The Dual-Phase-Lag (DPL) model refines this further by introducing separate time lags for heat flux and temperature gradient, allowing the simulation of delayed onset and localized retention of heat within the PCM region. This more nuanced temperature inflection near layer boundaries demonstrates the capacity of non-Fourier models to capture delayed thermal communication between suit layers—a phenomenon particularly important in layered, pressure-compressed, phase change-enhanced garments. Such modeling supports the study’s central novelty: offering a physically realistic simulation framework that explicitly couples pressure effects, latent heat dynamics, and internal heat generation, while incorporating advanced transport models for transient behavior.

From an engineering perspective, these results underscore the need for careful selection and placement of PCM layers to maximize the phase transition plateau effect. By optimizing thickness and material properties in conjunction with pressure-aware design, manufacturers can enhance diver thermal protection and prolong safe exposure times. The demonstrated sensitivity of thermal performance to pressure-dependent conductivity also confirms that depth-aware suit design is essential for high-performance cold-water operations.

Nevertheless, the current model has limitations. The one-dimensional framework does not capture lateral thermal gradients or complex three-dimensional deformations of suit layers under real diving conditions. Metabolic heat generation is represented by an idealized exponential decay, without accounting for diver activity variability. Material properties are treated as homogeneous within layers, which may oversimplify real composite textiles with heterogeneous structures.

Despite these simplifications, this work lays a strong foundation for the future development of smart thermal garment design tools. The integration of pressure-sensitive properties, explicit PCM buffering, metabolic heating, and non-Fourier transport models offers a comprehensive and versatile computational framework. It advances academic understanding of underwater heat transfer while directly informing engineering decisions for next-generation protective gear.

6. Conclusions

This study developed a detailed mathematical and numerical framework to investigate transient heat transfer in cold-water diving suits incorporating pressure-sensitive phase change materials (PCMs). The proposed model uniquely combines hydrostatic pressure–dependent reductions in thermal conductivity, internal metabolic heat generation, and latent heat buffering via an explicit front-tracking mechanism. This multi-layer approach, along with the implementation of a non-Fourier formulation using similarity transformation, provides a comprehensive and physically grounded simulation of thermal behavior under high-pressure, cold-water immersion.

The simulation results demonstrate the emergence of a thermal plateau near the PCM melting temperature, confirming the effectiveness of phase change materials in stabilizing local temperatures and delaying heat loss to the environment. Additionally, the pressure-induced decrease in thermal conductivity enhances insulation as depth increases, further contributing to improved thermal retention. Sensitivity analyses highlight the critical influence of PCM properties, metabolic heat generation, and pressure coefficients on the overall thermal response.

These findings offer valuable insights for the design and optimization of next-generation smart thermal garments, particularly for applications involving prolonged exposure to extreme underwater conditions. By accounting for realistic thermophysical changes due to pressure and human heat production, the model advances current understanding of heat transport in wearable systems beyond conventional steady-state or idealized assumptions.

Furthermore, the framework introduced here lays the foundation for future research involving adaptive insulation technologies and real-time thermal regulation strategies. Extensions of this work may include the integration of coupled thermo-mechanical effects, multi-dimensional modeling, or experimental validation using embedded sensor data and advanced smart textiles. The methodology also holds promise for broader applications in cryotherapy, aerospace thermal gear, and biomedical protective wear, where thermal stability under dynamic and harsh conditions is essential.

Overall, this study bridges the gap between theoretical thermal physics and practical engineering, offering a versatile tool for researchers and designers working on high-performance thermal protection systems in extreme environments.

6.1. Future Implementation and Application Outlook

Future research should focus on experimental calibration of pressure-dependent thermal properties using controlled laboratory setups to validate the model’s predictions against real measurement data. Extending the framework to two- or three-dimensional geometries will enable realistic representation of body-suit interactions, including non-uniform compression, lateral heat flow, and complex layer interfaces.

Additionally, integrating variable metabolic heat generation profiles informed by diver physiology and activity will improve prediction accuracy. Coupling the model with real-time control systems that leverage embedded sensor data—for example, skin temperature, depth, and suit compression—can enable adaptive responses such as activating local heating elements or releasing PCM capsules as needed.

Machine learning models trained on simulation outputs could enable lightweight, real-time approximations of thermal states on embedded microcontrollers, facilitating intelligent control without heavy computational loads. The model can guide the design of zoned insulation layouts, where different PCMs or materials are strategically placed to match anticipated heat loss profiles.

Ultimately, these advances will enable the development of intelligent thermal protection systems for divers, offering enhanced safety, endurance, and comfort under extreme underwater conditions. Beyond diving, the same modeling framework has potential applications in biomedical garments, cryotherapy suits, and aerospace thermal gear—demonstrating its broader relevance to smart wearable technology design.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The simulation code and data supporting this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the simulation results and assess the influence of key thermal and physiological parameters on the model output, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis varied one parameter at a time while keeping others fixed at their nominal values, thereby identifying the parameters with the greatest impact on temperature distribution and phase change dynamics.

Appendix A.1. Parameters Considered

The following parameters were selected based on their known variability in biological tissues and their relevance to thermal modeling:

Thermal conductivity at surface ()

Depth attenuation coefficient for conductivity ()

Metabolic heat generation at surface ()

Depth attenuation coefficient for metabolic power ()

Blood perfusion rate ()

Latent heat of fusion (L)

Effective heat capacity (c)

Each parameter was perturbed by relative to its baseline value, and the resulting effects on peak tissue temperature, thermal penetration depth, and extent of phase change were recorded.

Appendix A.2. Methodology

For each simulation, the primary metric of interest was the maximum temperature achieved within the tissue domain, as well as the total volume of tissue experiencing a phase change (defined by exceeding a threshold temperature range ).

The governing equations were solved numerically using a finite difference method with implicit time integration. Spatial and temporal discretization sizes were verified to ensure grid-independent results. The results of the sensitivity analysis are summarized in

Table A1. Among all parameters, thermal conductivity and blood perfusion showed the strongest influence on peak temperature, consistent with the dominant role of conductive and convective heat transfer in biological tissues.

Table A1.

Sensitivity of thermal response metrics to variation in model parameters. Values represent percent change relative to baseline simulation.

Table A1.

Sensitivity of thermal response metrics to variation in model parameters. Values represent percent change relative to baseline simulation.

| Parameter |

Peak Temperature Change (%) |

Phase Change Volume (%) |

Thermal Penetration Depth (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| L |

|

|

|

| c |

|

|

|

References

- Wei, T.; Ye, Z.; Zheng, B. Application Performance and Numerical Analysis of Phase Change Diving Suit. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Manufacturing Science and Engineering. Atlantis Press; 2015; pp. 538–542. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.B. Empirical evaluation of diving wet suit material heat transfer and thermal conductivity. Heat transfer engineering 1993, 14, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutil, Y.; Rousse, D.R.; Salah, N.B.; Lassue, S.; Zalewski, L. A review on phase-change materials: Mathematical modeling and simulations. Renewable and sustainable Energy reviews 2011, 15, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singal, S.K.; et al. Review of mathematical modeling on latent heat thermal energy storage systems using phase-change material. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2008, 12, 999–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S. Advancements in Phase Change Materials: Stabilization Techniques and Applications. Advancements in Phase Change Materials: Stabilization Techniques and Applications, 2024; pp. 254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Multiscale Modeling of Phase Change in Porous Media Using the Lattice Boltzmann Method. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2023, 200, 123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.L.; Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Tao, W.Q. Lattice Boltzmann methods for single-phase and solid-liquid phase-change heat transfer in porous media: A review. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 129, 160–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghoei, M.M.; Astanbous, A.; Khaksar, R.Y.; Moezzi, R.; Behzadian, K.; Annuk, A.; Gheibi, M. Phase change materials (PCM) as a passive system in the opaque building envelope: A simulation-based analysis. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MANSUETI, L.E.; GIANOLI, R. Transient simulation of phase change material (PCM) storage integrated in a domestic hot water (DHW) heat pump system 2016.

- Attinger, D.; Frankiewicz, C.; Betz, A.R.; Schutzius, T.M.; Ganguly, R.; Das, A.; Kim, C.J.; Megaridis, C.M. Surface engineering for phase change heat transfer: A review. MRS Energy & Sustainability 2014, 1, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubadi, H.H. ; Others. Heat and Mass Transfer of a Micropolar Nanofluid in a Ciliated Asymmetric Microchannel: Modeling Male Reproductive Physiology. Submitted/Published Journal Name, 2024; Preprint or in submission. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).