Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

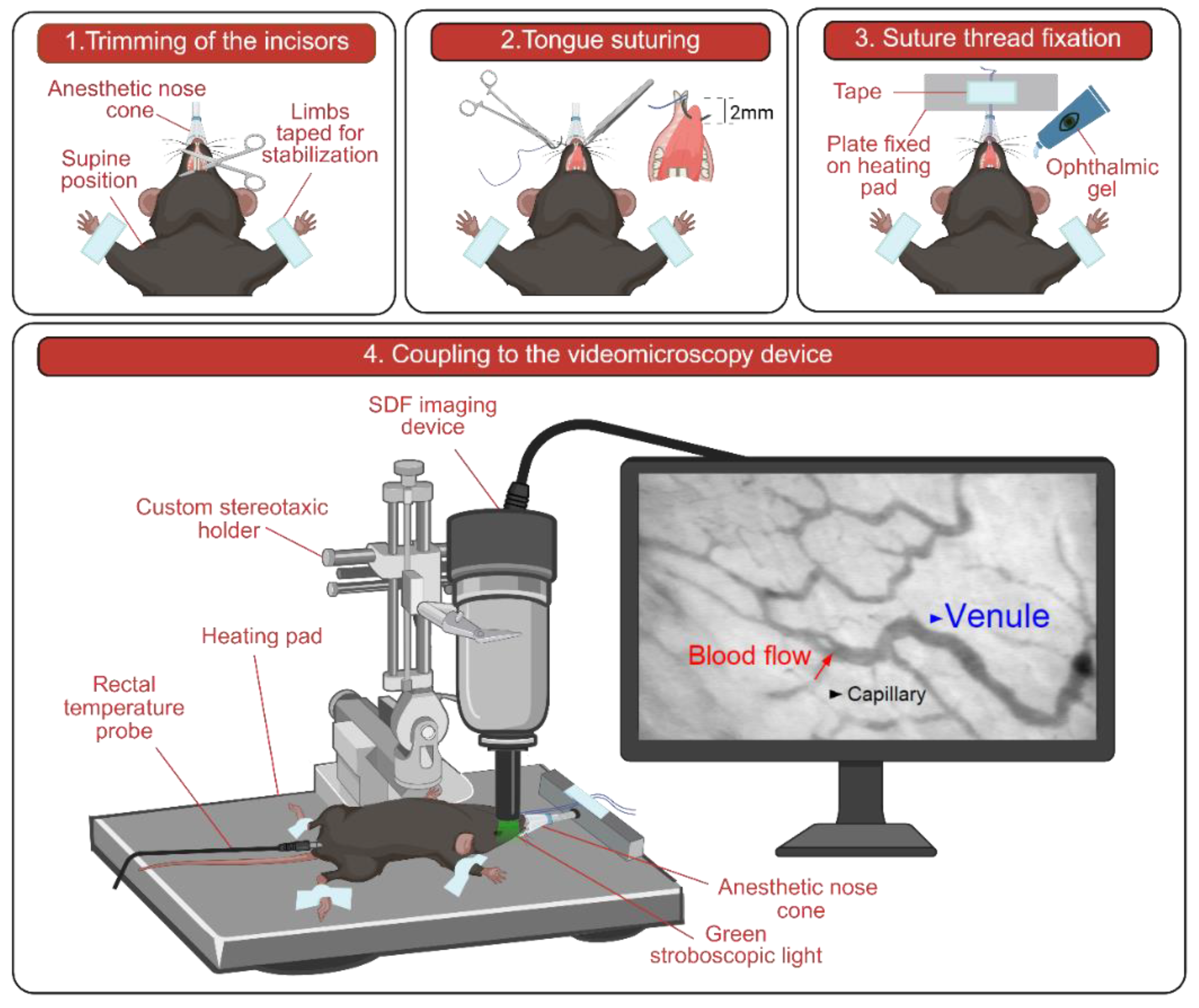

2.2. Mouse Preparation for In Vivo Imaging

2.3. Setup and Image Acquisition

2.4. Image Analysis

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

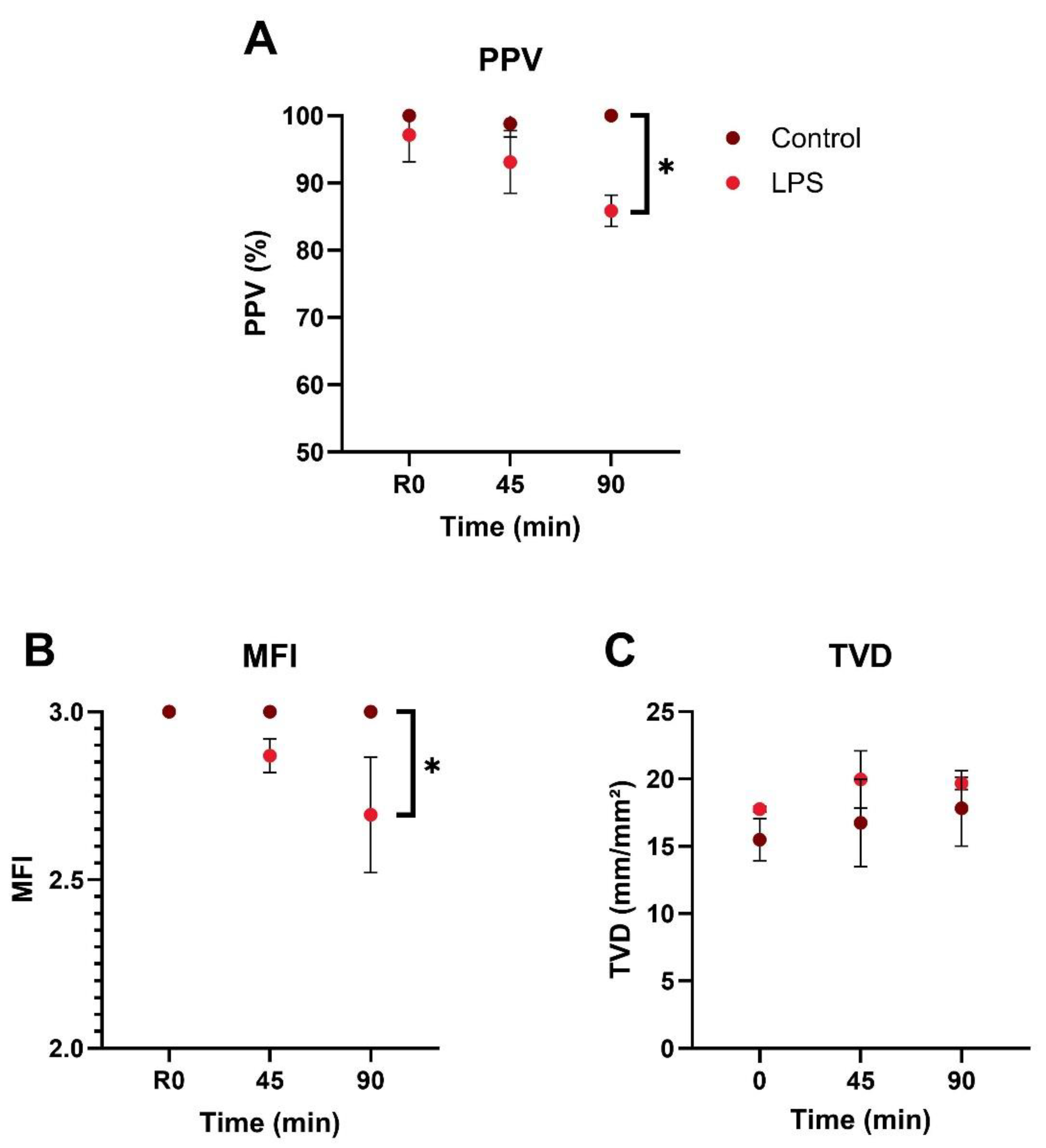

3.1. Microcirculatory Perfusion

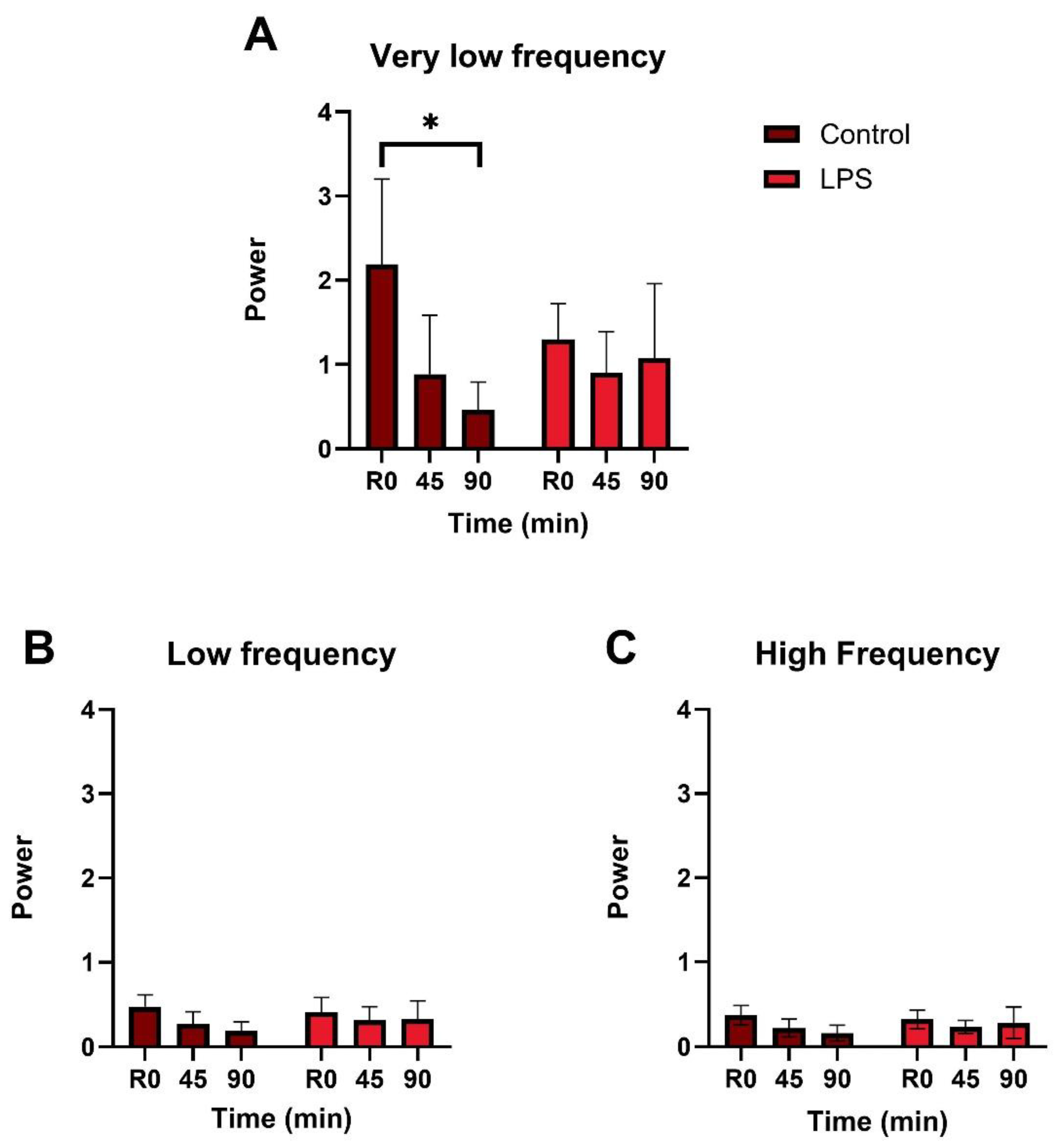

3.2. Vasomotion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Singer et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. De Backer, D. O. D. De Backer, D. O. Cortes, K. Donadello, and J. L. Vincent Pathophysiology of microcirculatory dysfunction and the pathogenesis of septic shock. 2014, Taylor and Francis Inc. [CrossRef]

- G. Guven, M. P. Hilty, and C. Ince Microcirculation: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Application. Blood Purif 2020, 49, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Damiani et al. Microcirculation-guided resuscitation in sepsis: the next frontier?. 2023, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- D. De Backer, F. D. De Backer, F. Ricottilli, and G. A. Ospina-Tascón Septic shock: A microcirculation disease. Apr. 01, 2021, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- C. Lelubre and J. L. Vincent Mechanisms and treatment of organ failure in sepsis. Jul. 01, 2018, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Ellis, R. M. C. G. Ellis, R. M. Bateman, M. D. Sharpe, W. J. Sibbald, and R. Gill Effect of a maldistribution of microvascular blood flow on capillary O 2 extraction in sepsis. 2002. [Online]. Available: www.ajpheart.

- H. Nilsson Vasomotion: Mechanisms and Physiological Importance. Mol Interv 2003, 3, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Aalkjær, D. C. Aalkjær, D. Boedtkjer, and V. Matchkov Vasomotion – what is currently thought?. 2011, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. Intaglietta Vasomotion and flowmotion: physiological mechanisms and clinical evidence. Vascular Medicine Review 1990, 1, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- P. M. Kowalewska et al. Spectroscopy detects skeletal muscle microvascular dysfunction during onset of sepsis in a rat fecal peritonitis model. M. Kowalewska et al. Spectroscopy detects skeletal muscle microvascular dysfunction during onset of sepsis in a rat fecal peritonitis model. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Mendelson et al. Dynamic tracking of microvascular hemoglobin content for continuous perfusion monitoring in the intensive care unit: pilot feasibility study. J Clin Monit Comput 2021, 35, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Eskandari et al. Non-invasive point-of-care optical technique for continuous in vivo assessment of microcirculatory function: Application to a preclinical model of early sepsis. FASEB Journal, 2024; 23. [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, M. Larsson, T. Strömberg, and F. Iredahl Vasomotion analysis of speed resolved perfusion, oxygen saturation, red blood cell tissue fraction, and vessel diameter: Novel microvascular perspectives. Skin Research and Technology 2022, 28, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. Yajnik and R. Maarouf Sepsis and the microcirculation: The impact on outcomes. Apr. 01, 2022, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Tang, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Prognostic Value of Sublingual Microcirculation in Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med 2024, 39, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. S. K. Edul, C. Enrico, B. Laviolle, A. R. Vazquez, C. Ince, and A. Dubin Quantitative assessment of the microcirculation in healthy volunteers and in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 2012, 40, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. De Backer et al. The effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory alterations in patients with septic shock are independent of its systemic effects. Crit Care Med 2006, 34, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. J. Massey et al. Microcirculatory perfusion disturbances in septic shock: Results from the ProCESS trial. Crit Care, 2018; 1. [CrossRef]

- D. De Backer et al. Microcirculatory alterations in patients with severe sepsis: Impact of time of assessment and relationship with outcome. Crit Care Med 2013, 41, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. M. Bateman, M. D. R. M. Bateman, M. D. Sharpe, and C. G. Ellis Bench-to-bedside review: Microvascular dysfunction in sepsis - Hemodynamics, oxygen transport, and nitric oxide. Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. Lala, R. Homes, S. Pratt, W. Goodwin, and M. Midwinter Comparison of sublingual microcirculatory parameters measured by sidestream darkfield videomicroscopy in anesthetized pigs and adult humans. Animal Model Exp Med 2023, 6, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Bar et al. EARLY AND CONCOMITANT ADMINISTRATION OF NOREPINEPHRINE AND ILOMEDIN IMPROVES MICROCIRCULATORY PERFUSION WITHOUT IMPAIRING MACROCIRCULATION IN AN INTESTINAL ISCHEMIA-REPERFUSION INJURY SWINE MODEL: A RANDOMIZED EXPERIMENTAL TRIAL. Shock 2025, 63, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Wang et al. Effects of Methylprednisolone on Myocardial Function and Microcirculation in Post-resuscitation: A Rat Model. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Ge et al. Effects of Polyethylene Glycol-20k on Coronary Perfusion Pressure and Postresuscitation Myocardial and Cerebral Function in a Rat Model of Cardiac Arrest. J Am Heart Assoc, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Ferrara et al. Intestinal and sublingual microcirculation are more severely compromised in hemodilution than in hemorrhage. J Appl Physiol 2016, 120, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takala and S., M. Jakob Shedding light on microcirculation? Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Hessler et al. Monitoring of Conjunctival Microcirculation Reflects Sublingual Microcirculation in Ovine Septic and Hemorrhagic Shock. Shock 2019, 51, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Astapenko et al. Effect of acute hypernatremia induced by hypertonic saline administration on endothelial glycocalyx in rabbits. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2019, 72, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Zhang et al. Time of dissociation between microcirculation, macrocirculation, and lactate levels in a rabbit model of early endotoxemic shock. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 2153–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Dostalova et al. The Effect of Fluid Loading and Hypertonic Saline Solution on Cortical Cerebral Microcirculation and Glycocalyx Integrity. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2019, 31, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. M. J. Milstein, R. Helmers, S. Hackmann, C. N. W. Belterman, R. A. van Hulst, and J. de Lange Sublingual microvascular perfusion is altered during normobaric and hyperbaric hyperoxia. Microvasc Res 2016, 105, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. T. Goedhart et al. Imaging systems; (110.0180) Microscopy; (170.5380). 1977.

- Jiang, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Imaging and observation of microcirculation in bowel mucosa using sidestream dark field imaging. J Microsc 2025, 297, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Xu et al. Real-time semi-quantitative assessment of anastomotic blood perfusion in mini-invasive rectal resections by Sidestream Dark Field (SDF) imaging technology: a prospective in vivo pilot study. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 2023; 1. [CrossRef]

- B. W. Zweifach Direct observation of the mesenteric circulation in experimental animals. Anat Rec 1954, 120, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. N. E. Gavins and B. E. Chatterjee Intravital microscopy for the study of mouse microcirculation in anti-inflammatory drug research: Focus on the mesentery and cremaster preparations. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2004, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, M. H. Oktay, J. S. Condeelis, and D. Entenberg Intravital Imaging Techniques for Biomedical and Clinical Research. , 2020, Wiley-Liss Inc. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- J. Pittet and R. Weissleder Intravital imaging. Nov. 23, 2011, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. J. J. Kwok, and S. H. Yun In vivo fluorescence microscopy: Lessons from observing cell behavior in their native environment. Jan. 01, 2015, American Physiological Society. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Silva, M. A. R. B. Castanho, and A. S. Silva-Herdade Towards Non-Invasive Intravital Microscopy: Advantages of Using the Ear Lobe Instead of the Cremaster Muscle. Life. [CrossRef]

- T. Kurata, Z. Li, S. Oda, H. Kawahira, and H. Haneishi Impact of vessel diameter and bandwidth of illumination in sidestream dark-field oximetry. Biomed Opt Express 2015, 6, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. Jansen et al. Applicability of quantitative optical imaging techniques for intraoperative perfusion diagnostics: a comparison of laser speckle contrast imaging, sidestream dark-field microscopy, and optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt, 2017; 08. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Shultz, F. L. D. Shultz, F. Ishikawa, and D. L. Greiner Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Gengenbacher, M. Singhal, and H. G. Augustin Preclinical mouse solid tumour models: Status quo, challenges and perspectives. Dec. 01, 2017, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- S. Seemann, F. S. Seemann, F. Zohles, and A. Lupp Comprehensive comparison of three different animal models for systemic inflammation. J Biomed Sci, 2017; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. M. Treu, O. C. M. Treu, O. Lupi, D. A. Bottino, and E. Bouskela Sidestream dark field imaging: The evolution of real-time visualization of cutaneous microcirculation and its potential application in dermatology. Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Wood et al. The Use of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and/or Transcranial Doppler as Non-Invasive Markers of Cerebral Perfusion in Adult Sepsis Patients With Delirium: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med 2022, 37, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Jul. 2012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. McDowell, A. A. Berthiaume, T. Tieu, D. A. Hartmann, and A. Y. Shih VasoMetrics: Unbiased spatiotemporal analysis of microvascular diameter in multi-photon imaging applications. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021, 11, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. C. Boerma, K. R. E. C. Boerma, K. R. Mathura, P. H. J. van der Voort, P. E. Spronk, and C. Ince Quantifying bedside-derived imaging of microcirculatory abnormalities in septic patients: a prospective validation study. Crit Care, 2005; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang et al. Tumor-Derived Exosomes Promote Tumor Growth Through Modulating Microvascular Hemodynamics in a Human Ovarian Cancer Xenograft Model. Microcirculation, 2024; 7. [CrossRef]

- Spanos, S. Jhanji, A. Vivian-Smith, T. Harris, and R. M. Pearse Early microvascular changes in sepsis and severe sepsis. Shock 2010, 33, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Inoue, K. S. Inoue, K. Suzuki-Utsunomiya, K. Suzuki-Utsunomiya, T. Sato, T. Chiba, and K. Hozumi Impaired innate and adaptive immunity of accelerated-aged Klotho mice in sepsis. Crit Care, 2012; S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. S. Taccone et al. Cerebral microcirculation is impaired during sepsis: An experimental study. Crit Care, 2010; 4. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Verdant et al. Evaluation of sublingual and gut mucosal microcirculation in sepsis: A quantitative analysis. Crit Care Med 2009, 37, 2875–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Secor et al. Impaired microvascular perfusion in sepsis requires activated coagulation and P-selectin-mediated platelet adhesion in capillaries. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36, 1928–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R. Patil, S. Mani, M. R, and H. R. Vasanthi Refinement of LPS induced Sepsis in SD Rats to Mimic Human Sepsis. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal 2020, 13, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. T. Cornell, P. Rodenhouse, Q. Cai, L. Sun, and T. P. Shanley Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 2 regulates the inflammatory response in sepsis. Infect Immun 2010, 78, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiyama, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. P-selectin-dependent monocyte recruitment through platelet interaction in intestinal microvessels of LPS-treated mice. Microcirculation 2008, 15, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. F. Liu, A. B. Malik, and S. F. Liu NF-B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006, 290, 622–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Hernandez, A. Bruhn, and C. Ince Microcirculation in Sepsis: New Perspectives. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2013, 11, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Ince and M. Sinaasappel Microcirculatory oxygenation and shunting in sepsis and shock. Crit Care Med 1999, 27, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Trzeciak et al. Resuscitating the microcirculation in sepsis: The central role of nitric oxide, emerging concepts for novel therapies, and challenges for clinical trials. 08. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- D. Lidington, Y. Ouellette, F. Li, and K. Tyml Conducted vasoconstriction is reduced in a mouse model of sepsis. J Vasc Res 2003, 40, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Ince The microcirculation is the motor of sepsis. Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- K. Tyml, X. K. Tyml, X. Wang, D. Lidington, and Y. Ouellette Our recent in vitro study (Lidington et al. 2001. [Online]. Available: www.ajpheart.

- R. Condon, J. E. Kim, E. A. Deitch, G. W. Machiedo, and Z. Spolarics Downloaded from journals.physiology.org/journal/ajpheart at Dalhousie Univ DAL 11762. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003, 284, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. J. Singel and J. S. Stamler Chemical physiology of blood flow regulation by red blood cells: The role of nitric oxide and S-nitrosohemoglobin. 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Miranda, M. Balarini, D. Caixeta, and X. Eliete Bouskela Microcirculatory dysfunction in sepsis: pathophysiology, clinical monitoring, and potential therapies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016, 311, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Nyvad et al. Intravital investigation of rat mesenteric small artery tone and blood flow. Journal of Physiology 2017, 595, 5037–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Kvietys and D. N. Granger Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the vascular responses to inflammation. Feb. 01, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Goldman and A. S. Popel A computational study of the effect of vasomotion on oxygen transport from capillary networks. J Theor Biol 2001, 209, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. P. Dellinger et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013, 39, 165–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Roger et al. Time course of fluid responsiveness in sepsis: The fluid challenge revisiting (FCREV) study. Crit Care, 20 May; 1. [CrossRef]

- E. Farkas and P. G. M. Luiten Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. 2001. [Online]. Available: www.elsevier.

- S. D. Hutchings, J. S. D. Hutchings, J. Wendon, S. Watts, and E. Kirkman The Cytocam video microscope. A new method for visualising the microcirculation using incident dark field (IDF) technology. 2015, SpringerOpen. [CrossRef]

- J. Han, P. J. Han, P. Choi, and M. Choi µTongue: A Microfluidics-Based Functional Imaging Platform for the Tongue In Vivo. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Choi, W. M. M. Choi, W. M. Lee, and S. H. Yun Intravital microscopic interrogation of peripheral taste sensation. Sci Rep, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. Hammoudeh et al. Tongue orthotopic xenografts to study fusion-negative rhabdomyosarcoma invasion and metastasis in live animals. Cell Reports Methods 2024, 4, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).