The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region, home to over 1.7 billion people, has undergone significant transformations in mortality patterns over the last three decades. However, by 2019, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) — particularly cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), diabetes, chronic respiratory conditions, and cancers — became the leading causes of death, reflecting broader global health trends influenced by urbanization, changing lifestyles, and environmental factors [

1,

2].

Human mortality arises from a diverse range of factors, including high systolic blood pressure, alcohol use, smoking, air pollution, drug use, vitamin A deficiency, iron deficiency, meningitis, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, Parkinson’s disease, malaria, drowning, interpersonal violence, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, cardiovascular diseases, lower respiratory infections, self-harm, diarrheal diseases, environmental heat and cold exposure, conflict and terrorism, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, poisonings, road injuries, chronic respiratory diseases, digestive diseases, and exposure to fire, heat, and hot substances [

1,

2].

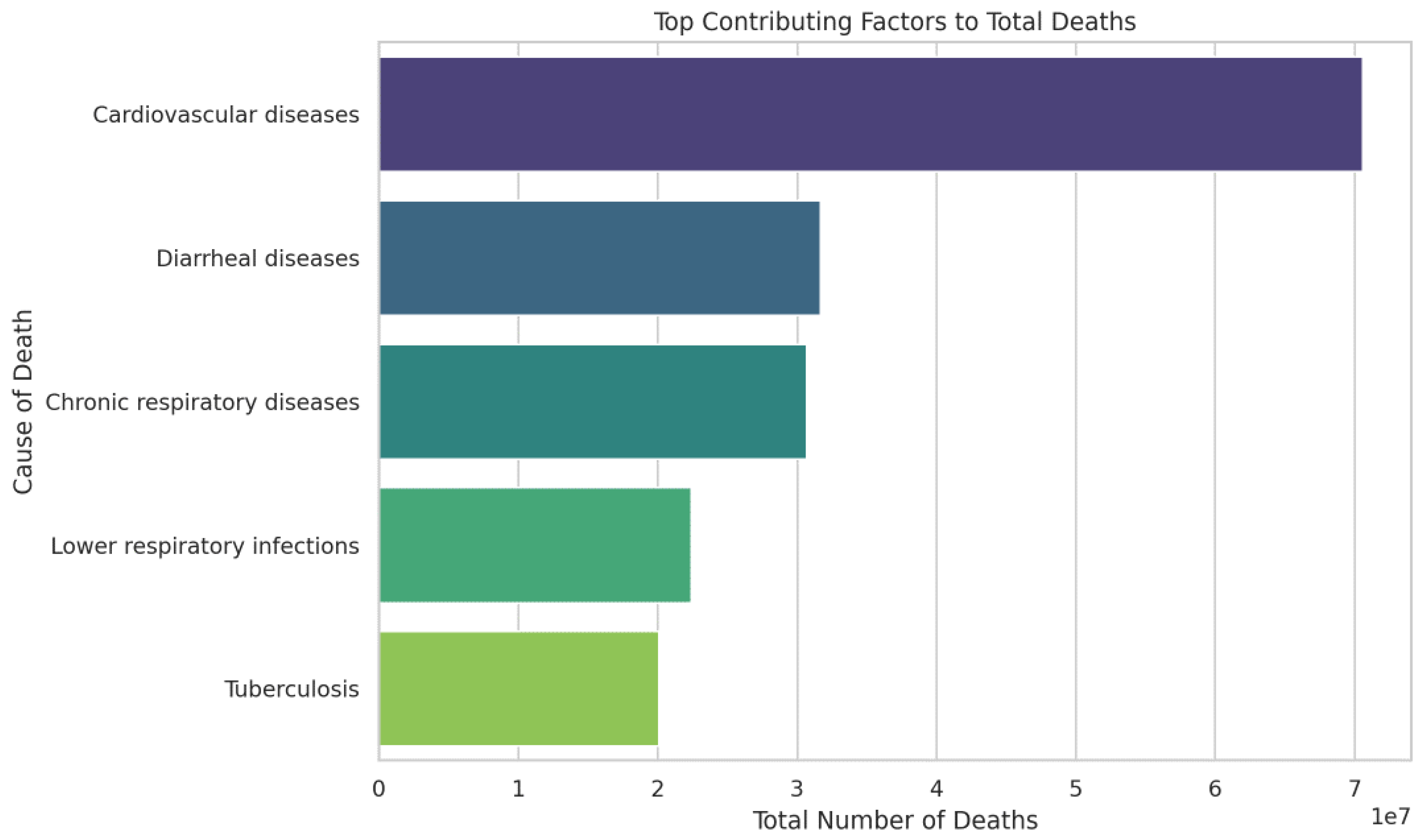

Figure 1 highlights the top causes of death in SAARC nations from 1990 to 2019, offering a clear representation of how mortality patterns have shifted across the region. CVDs have emerged as the leading cause of death, a trend driven by increasing urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, poor dietary habits, and rising rates of hypertension and diabetes. Following CVDs, diarrheal diseases remain a significant cause of mortality where access to clean water and adequate sanitation remains limited. These conditions disproportionately affect children under five, contributing to high child mortality rates in these regions. Chronic respiratory conditions, such as COPD and lower respiratory tract infections, ranked third and fourth among the leading causes of death. These diseases are especially prevalent in countries, where indoor air pollution, combined with poor outdoor air quality, exacerbates respiratory health problems. Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis ranked fifth among the diseases remain significant causes of mortality. In summary,

Figure 1 not only illustrates the leading causes of death in SAARC nations but also underscores the complex interplay between non-communicable and communicable diseases, alongside environmental factors.

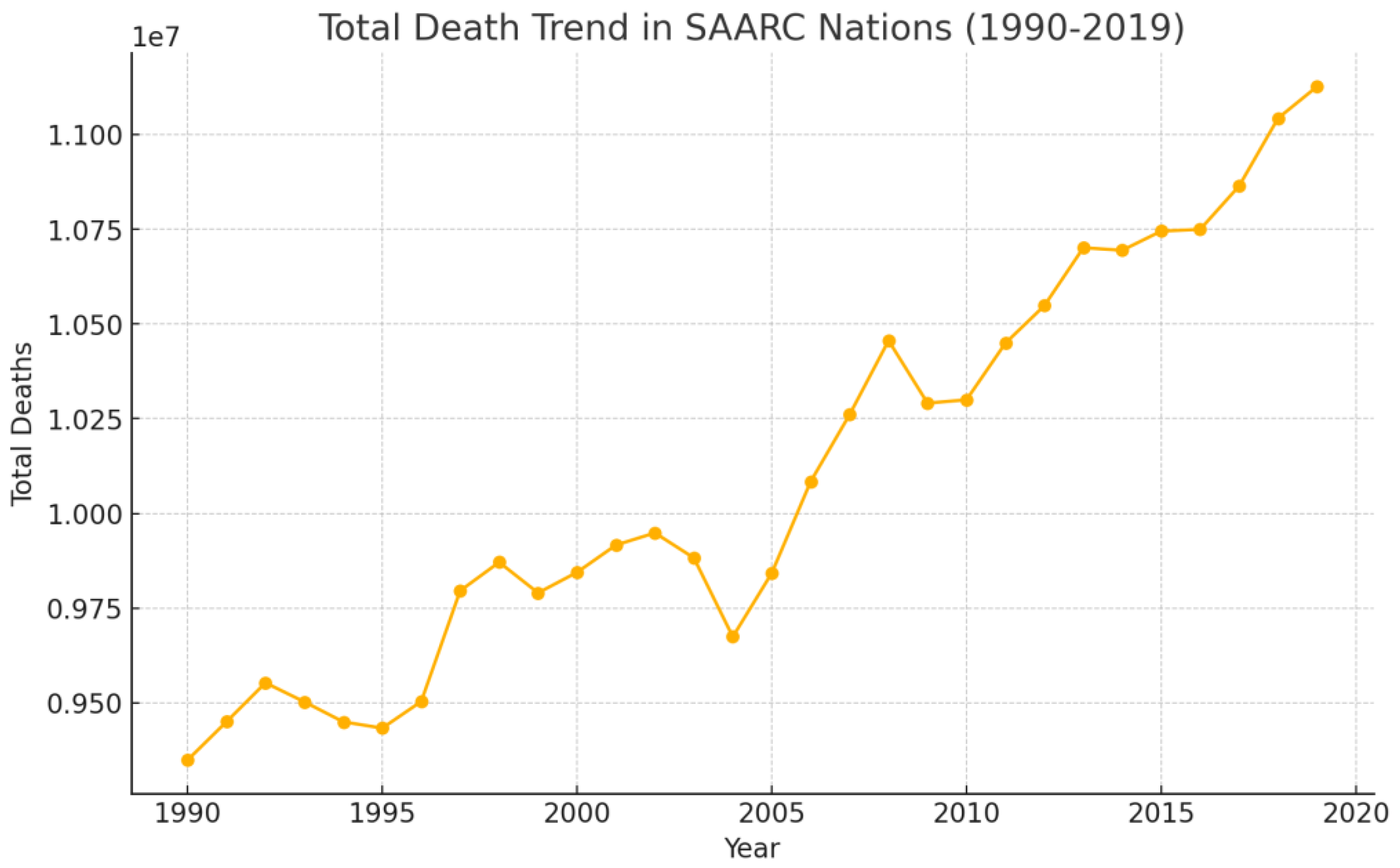

The trend of total deaths in the SAARC nations from 1990 to 2019 shows a steady increase, with notable periods of acceleration and stabilization as presented in

Figure 2. In the early 1990s, the rise in deaths was gradual, largely driven by the widespread prevalence of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases, and lower respiratory infections. By the end of the 1990s, public health initiatives such as immunization campaigns, improved sanitation, and expanded access to healthcare contributed to a reduction in deaths from communicable diseases in some countries, though population growth continued to drive moderate increases in overall deaths [

3]. From 2000 to 2005, there was some stabilization in the overall death trend, particularly in countries like India and Sri Lanka, where child mortality, maternal health, and communicable diseases were addressed through public health interventions [

4]. Between 2005 and 2010, the trend of total deaths began to sharply increase, largely due to the rising burden of NCDs across the region. Urbanization, lifestyle changes such as rising rates of hypertension, smoking, and obesity, and the aging population contributed to a surge in mortality related to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and chronic respiratory conditions [

3]. By this time, NCDs had become the leading cause of death in many SAARC countries, while some areas still struggled with communicable diseases and maternal health issues [

5,

6]. From 2010 to 2019, the death toll continued to rise steadily, driven largely by the escalating burden of NCDs, especially in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh [

1]. The combination of an aging population and increasing rates of lifestyle-related conditions such as diabetes and hypertension contributed to the steady growth in overall deaths [

7].

Table 1 presents the Human Development Indices (HDIs) of the SAARC nations from 1990 to 2019. The data from 1990 to 2015 is present in five-year intervals, followed by 2017 to 2019. Afghanistan experienced erratic mortality rates, reflecting ongoing conflict and instability, but its HDI showed consistent improvement from 2005 onward, reaching 0.511 by 2019. Bangladesh’s mortality rate declined significantly until 2005, then plateaued and increased slightly in the years that followed, aligning with its steady HDI growth from 0.387 in 1990 to 0.632 in 2019. Bhutan’s improvements in HDI, from 0.51 in 2005 to 0.654 in 2019, reflects advancements in health and education and aligns with declining mortality rates until 2005 and a stable period afterward. India achieved a consistent HDI growth, reaching from 0.427 in 1990 to 0.645 in 2019, but with slight rise in mortality rates during certain intervals, indicating a modest fluctuation due to its ongoing demographic and healthcare challenges. The Maldives exhibited consistently low mortality rates, with an HDI increase from 0.539 in 1995 to 0.74 in 2019, indicative of its strong reformation in social and healthcare policies. Nepal’s mortality rates initially declined but showed variability after 2005, due to the subsequent stabilization, reflecting its HDI growth from 0.378 in 1990 to 0.602 in 2019. Pakistan’s mortality rates remained stable with slight increases, and its HDI growth slowed after 2015, reaching 0.557. Sri Lanka showed a unique trend of mortality rate increases coupled with the highest initial HDI of 0.625 among the SAARC regions in 1990, and steadily improving to 0.782 by 2019. The results for the Maldives and Sri Lanka also reflect their highest literacy rates among SAARC nations, being 97% and 92%, respectively.

The SAARC region have experienced significant shifts in their mortality patterns between 1990 and 2019, shaped by varying socioeconomic, environmental and healthcare conditions, with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) increasingly accounting for the majority of deaths. The transition from communicable to NCDs has been a predominant trend across these nations. These NCDs include high systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and chronic respiratory diseases, alongside persistent environmental health challenges like air pollution [

8,

9].

Afghanistan continues to face high mortality rates driven by decades of conflict, weakened healthcare infrastructure, and the prevalence of communicable diseases. The maternal mortality rate remains among the highest globally, with infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria contributing significantly to mortality [

10,

11]. Essar et al. [

12] highlight that strategies to improve Afghanistan’s health system must address both acute conflict-related challenges and long-term infrastructure rebuilding efforts.

Bangladesh has made significant progress in reducing mortality rates over the last three decades, particularly through improvements in maternal and child health [

13,

14]. However, air pollution and increasing rates of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases pose significant threats to health outcomes. The World Bank [

15] emphasizes that while public health initiatives have reduced mortality rates, environmental risks like air pollution continue to hinder progress.

Bhutan has maintained relatively low mortality rates due to its small population and advancements in healthcare accessibility. Its success is largely attributed to government investments in healthcare and education, fostering improvements in life expectancy and reductions in communicable diseases [

16,

17,

18].

India exhibits a dual burden of diseases, with NCDs like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes becoming the leading causes of death, especially in urban areas. According to Dans et al. [

19], this trend reflects rapid urbanization, lifestyle changes, and aging population [

20,

21]. Simultaneously, the persistence of diseases like tuberculosis underscores gaps in healthcare access for marginalized communities.

The Maldives has consistently recorded the lowest mortality rates among SAARC nations. This achievement is largely attributed to its robust healthcare system and effective public health campaigns targeting both communicable and non-communicable diseases. The country’s high HDI, which increased from 0.539 in 1995 to 0.74 in 2019, underscores its healthcare and socio-economic progress.

Nepal faces significant healthcare challenges due to its geographical terrain and limited healthcare resources. Despite reductions in mortality from communicable diseases, NCDs now account for a rising proportion of deaths. According to WHO [

22], Nepal’s multisectoral action plan for NCDs has shown promise in tackling this growing burden.

Pakistan’s mortality trends reflect a challenging healthcare landscape characterized by persistent infectious diseases like dengue fever and polio, alongside rising NCD rates. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [

23] reports that this dual burden is worsened by political instability and inadequate healthcare funding.

Sri Lanka stands out for its low mortality rates and effective management of NCDs. The establishment of Healthy Lifestyle Centers has been pivotal in screening and managing risk factors for NCDs. Glass et al. [

10] attribute Sri Lanka’s success to its robust healthcare policies and universal health coverage, which have minimized disparities in healthcare access.

The SAARC region faces dual health challenges: the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the fragility of healthcare systems in conflict-affected areas. NCDs like cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and chronic respiratory conditions are leading causes of death, especially in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh [

19]. While public health initiatives such as India’s National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Stroke (NPCDCS) and Bangladesh’s air quality improvements have shown potential, limited rural healthcare access and persistent environmental risks hinder their effectiveness [

15,

24]. Conversely, Sri Lanka has achieved notable success in combating NCDs due to its robust healthcare infrastructure and consistent policy implementation [

25,

26]. Meanwhile, countries like Afghanistan grapple with weakened healthcare systems exacerbated by decades of conflict, leading to high rates of maternal and infectious disease mortality [

10,

11,

12]. Nepal and Pakistan similarly struggle with the dual burden of NCDs and communicable diseases due to political instability and insufficient healthcare resources [

22,

23]. This highlights the urgent need for comprehensive strategies addressing both lifestyle and systemic health challenges across the region.

Conclusions

The SAARC region’s mortality trends reveal a complex interaction of socioeconomic, environmental, and healthcare factors. While countries like Sri Lanka and the Maldives demonstrate the positive impact of robust healthcare systems and consistent policy implementation, others, such as Afghanistan and Nepal, grapple with the dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases that are aggravated by political instability and limited resources. Progress in reducing mortality rates, as seen in Bangladesh and Bhutan, underscores the critical role of targeted investments in healthcare and education. Addressing persistent challenges requires a regional commitment to strengthening healthcare infrastructure, reducing disparities, and fostering sustainable public health initiatives. With coordinated efforts, the SAARC nations can continue their trajectory toward improved health outcomes and reduced mortality.

Data Availability Statement

AI Declaration

The authors used AI-assisted technology (ChatGPT-3.5) for language editing and grammar checking.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared that there is no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L. The Global Burden of Disease Study at 30 years. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran, D.; Jeemon, P.; Roy, A. Cardiovascular Diseases in India: Current Epidemiology and Future Directions. Circulation 2016, 133, 1605–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (2024). Maternal mortality. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.

- Bhuiyan, M.A.; Galdes, N.; Cuschieri, S.; Hu, P. A comparative systematic review of risk factors, prevalence, and challenges contributing to non-communicable diseases in South Asia, Africa, and Caribbeans. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 2024, 43, 140–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dans, A.; Ng, N.; Varghese, C.; Tai, E.S.; Firestone, R.; Bonita, R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in Southeast Asia: time for action. The Lancet (British Edition) 2011, 377, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Sandeep, S.; Deepa, R.; Shah, B.; Varghese, C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian Journal of Medical Research (New Delhi, India: 1994) 2012, 136, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S.S.; Phalkey, R.; Malik, A.A. A systematic review of air pollution as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in South Asia: Limited evidence from India and Pakistan. International journal of hygiene and environmental health 2014, 217, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. (2022). Striving for clean air: Air pollution and public health in South Asia. The World Bank Group. Retrieved January 2, 2025, from, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/59caa0ae9263d449e65281b635541828-0310012022/original/AirPollution-Highlights.pdf.

- Glass, N.; Jalalzai, R.; Spiegel, P.; Rubenstein, L. The crisis of maternal and child health in Afghanistan. Conflict and Health 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzazada, S.; Padhani, Z.A.; Jabeen, S.; Fatima, M.; Rizvi, A.; Ansari, U.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Impact of conflict on maternal and child health service delivery: A country case study of Afghanistan. Conflict and Health 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essar, M.Y.; Siddiqui, A.; Head, M.G. Infectious diseases in Afghanistan: Strategies for health system improvement. Health Science Reports 2023, 6, e1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA Bangladesh. (2020). Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response (MPDSR) annual report 2020. Retrieved from https://bangladesh.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/mpdsr_annual_report_2020_final.pdf.

- Hossain, A.T.; Hazel, E.A.; Rahman, A.E.; Koon, A.D.; Wong, H.J.; et al. Effective multi-sectoral approach for rapid reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality: The exceptional case of Bangladesh. BMJ Global Health 2024, 9 (Suppl. 2), e011407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. (2024, March 28). Addressing environmental pollution is critical for Bangladesh’s growth and development. Retrieved January 2, 2025, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/03/28/addressing-environmental-pollution-is-critical-for-bangladesh-s-growth-and-development.

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2018). Health sector assessment for Bhutan. Retrieved January 2, 2025, from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/51141-002-ssa.pdf.

- Dorji, T.; Dorji, N.; Yangdon, K.; Gyeltshen, D.; Tenzin, L. Exploring the ethical dilemmas in end-of-life care and the concept of a good death in Bhutan. Asian Bioethics Review 2022, 14, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yangchen, S.; Tobgay, T.; Melgaard, B. Bhutanese health and the health care system: Past, present, and future. The Druk Journal 2016, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dans, A.; Ng, N.; Varghese, C.; Tai, E.S.; Firestone, R.; Bonita, R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in Southeast Asia: time for action. Lancet 2011, 377, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Lubet, A.; Mitgang, E.; Mohanty, S.; Bloom, D.E. (2020). Population Aging in India: Facts, Issues, and Options. In: Poot, J., Roskruge, M. (eds) Population Change and Impacts in Asia and the Pacific. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives, Volume 30. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0230-4_13.

- Vijapur, V.B. Population aging in India: Issues, and challenges. International Journal of Physiology, Nutrition and Physical Education 2018, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Multisectoral action plan for prevention and control of NCDs (2014–2020): Nepal. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/multisectoral-action-plan-for-prevention-and-control-of-ncds-%282014-2020%29.pdf?sfvrsn=c3fa147c_4.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2023, January 18). Pakistan faces double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. Retrieved from https://www.healthdata.org/news-events/newsroom/news-releases/lancet-pakistan-faces-double-burden-communicable-non.

- Pati, M.K.; Bhojani, U.; Elias, M.A.; Srinivas, P.N. Improving access to medicines for non-communicable diseases in rural primary care: results from a quasi-randomized cluster trial in a district in South India. BMC Health Serv Res 2021, 21, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (MOH), Sri Lanka. (2010). National policy and strategic framework for prevention and control of chronic NCDs. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/13_NCD.pdf.

- Ministry of Health (MOH), Sri Lanka. (2019). Annual report 2019: Healthy Lifestyle Centres (Part 1). Retrieved from https://ncd.health.gov.lk/images/Annual_Report_2019_Part_1.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).