1. Introduction

Productivity is the fundamental basis of modern market power. Good products always wield a certain degree of it. Market power emerges from productivity and productivity growth. However, both productivity and productivity growth fluctuates, affecting profitability and returns. Their measurement with respect to scale economies have been studied by Morrison (1990) and Hall (1986), the fluctuations being primarily the effects of demand and supply shocks (Syverson, 2011), among many other causal factors. But to begin with, how do we define productivity, and how to give a precise definition of it?

“Productivity is a set of purposeful actions that translates into value—e.g., marketable goods and services. It is the dynamic driving force that powers the economy and economic elements that contribute to wealth creation and welfare.”

But there is a saying which goes as follows; behind the machinery there’s a brain. Let us extend it a bit forward: behind the brain there’s a mind with its “intellect.” Similarly, behind the machinery, production, and market power lies human effort, persistence, acumen, and discipline. Now, what actually ‘powers’ productivity? In essence, behind the driving forces of the economics of production and market power, it is human effort, productiveness, and intelligence that make everything else possible. Productivity—in this respect, is nothing but actions generated under “controlled” conditions, for nothing is created without being controlled by conditions. Productivity, as a result, exerts certain degree of power which is marketable, and hence, it is a market-power that drives the economy.

Productivity is generally studied using the principles of economics. The science of productivity concerns the microeconomic principles of demand function, utility theory, and consumption. It is generally observed that firms scale up their production rate in response to increased demand for goods due to expected increase in consumer demand and heightened consumption pattern as observed in seasonal demand shifts (Soysal & Krishnamurthi, 2012), and vice-versa. A general production “equilibrium” rate is achieved to adjust to new settings (Suzuki, 2009; Levinsohn & Melitz, 2002). In fact, many firms struggle to achieve this equilibrium state but fail to do so. In this research, our primary aim is to study the metaphysical aspects of productivity, production, and productivity growth (Koskela & Kagioglou, 2005). It is important to note that production is correlated to management (Koskela & Kagioglou, 2006) and vice versa, as both are interconnected and interdependent. But how these two are interconnected? These two are related by Total Factor Productivity (TFP).

Efficient management practices guide operations and bring innovations in production processes and products. Hence, it is the foundation of total factor productivity (TFP)

1, which explains production function in new light through examination of their nature, and with the aid of theoretical reasoning about how “refinement in processes” and methods leads to better outcome and higher productive efficiency (Fried, Schmidt & Lovell, 1993). The unexplained portion of output not determined by input functions is also explained, since beyond inputs, the efficiency factors come into play. These are in the tune of how efficiently the inputs are utilised to produce goods and services (Comin, 2006).

The Demand for Utility

First, it is imperative to understand the demand for utility that satisfies consumer choices and desires. Then, it need be understood the theory of possession, and the utility thus obtained from possessing certain goods and services. We call it the ‘utility of possession’. Which means that, utility fulfils consumer wants and desires of possessing a particular product or a collection of good and services. Second, we need to examine the productive utility from possessing certain products and the need for consumption that drives demand for goods and services. Third, the “economic significance” of productivity must be assumed insofar it concerns the tacit assumptions concerning the theory of productivity. And finally, the fourth aspect of study is to examine the economic significance of time, effort, and other endogenous and exogenous factors that influence productivity levels. This is for the purpose of obtaining the most definite assumptions about productivity function.

2. Forms of Productive Power

It must be understood beforehand that there are different forms of productivity characterising diverse practices according to which we may categorise it, e.g., social productivity, cultural productivity, artistic productivity, intellectual, individual, collective, and industrial forms of productivity—so to speak. Now, different degrees of power emanates from diverse forms of productivity. Take for example, there is power in industrial productivity as it is the core sector of major economies generating “employment” for the people. Industrial productivity—no doubt—drives the economy. It has the power to influence the people and their consumption habits and choices, and reciprocally, it is significantly affected by changing consumption patterns and habits, altered choices, and predilections of the consumers. Each forms of productivity has its own purposes and goals to achieve. However, in this research, our theme of study involves individual productivity, its essence, determinants, and dynamics. In this respect, a critical examination of the different factors that influence productivity is assumed in theory and practice (Syverson, 2011). For a detailed review of the causal aspects that determine productivity, see Danlami et. al., (2018).

Productivity depends—no, it is guaranteed, to a large extent, on the demand that a specific set of rules be followed. We may call it conditions for productivity. Productivity is a necessity to achieve higher goals and attain lofty aims. It serves purpose and has definite utility. We cannot avoid but invoke the theory of utility and relate it to productivity, in order to examine the concept of productive utility in some detail.

“There are factors that shape our capacity to create values, and there are factors that empower us to become resourceful and productive.”

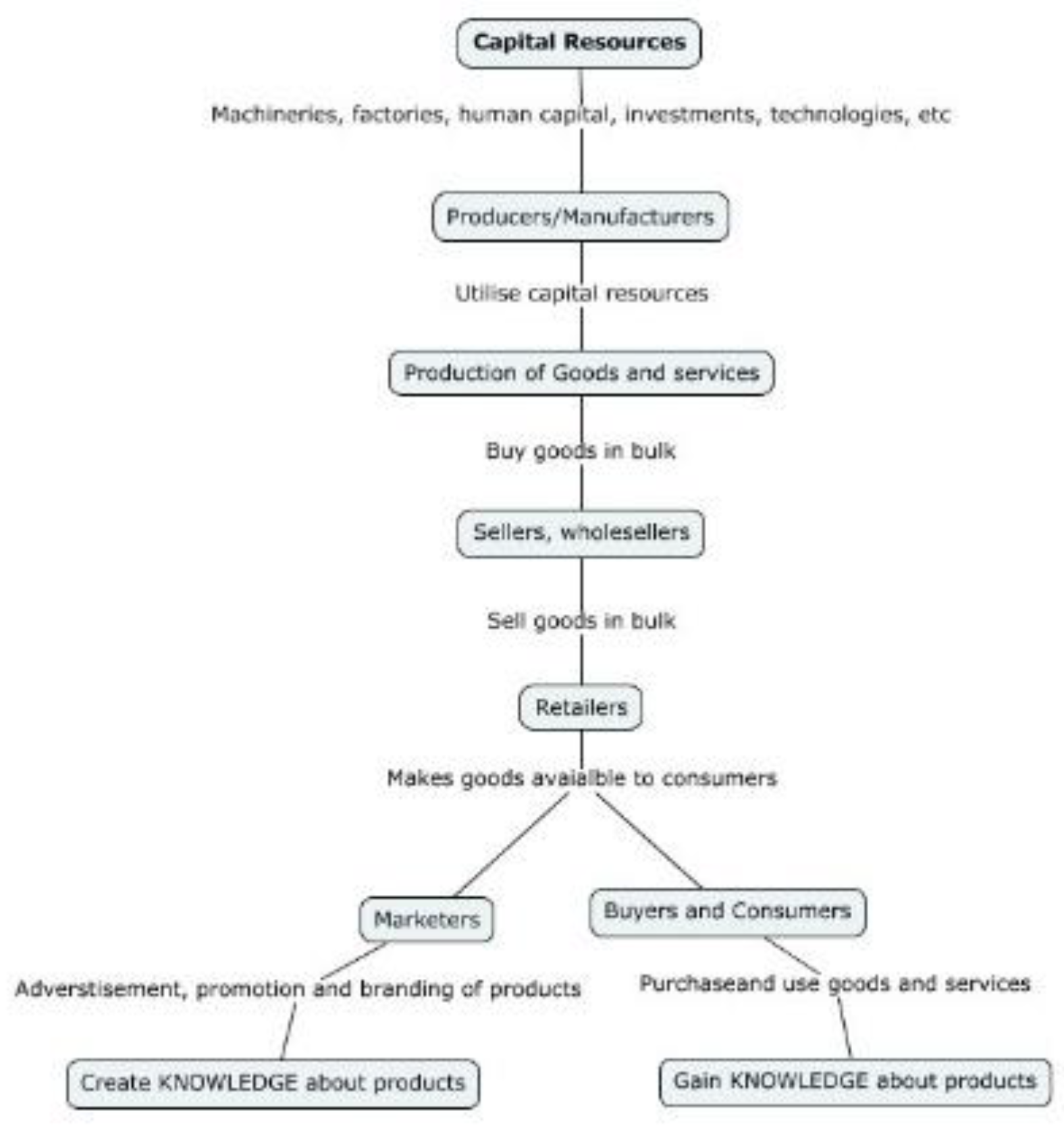

Creativity has utility and value. However, creativity, imagination, art, and social interactions are not effectively captured in conventional measurement of productivity. Some experts consider these factors as non-measurable things, and it has a philosophy which is different from that of the metaphysics of productivity. The productivity chain is described below in

Figure 1.

The philosophy and the economics of productivity depends mainly on the nature of efforts dedicated to achieve some definite end. Which means in terms of materialistic idealism the rational proceeds from practical efficiency of an originator, inventor, or initiator who’s doing something useful, and which has some utility and value. The “power” of productivity originates from the attained efficiency of the producer, as well as from the processes, methods, and techniques being followed. These are stated as “conditions” for productivity (Eichler et al., 2006; Danlami et al., 2018). These conditions are of much significance at the organisational (firm) level where tool use increases collective productivity and improves efficiency. The more advanced the tools are, the more powerful they become, and thus more efficient they are. Hence, the race for creating “productive tools” that bring improvements in productivity level has become the norm of the day. Proliferation of digital tools based on AI (artificial intelligence) is one of the glaring examples of the race for creation of productive apps and tools (Jorgenson, 2009).

The “power” working on productive processes is the main influence intrinsic to an organisation’s culture of practice. But what is this power—, and what about its nature and origin? By the power of “productive” efforts, it becomes possible for somebody to be at the “centre” of focus and attention, or to be at the top of the grid. Indeed, numerous anecdotal as well as material evidences point to this fact and thus provide legitimate proof of this phenomenon. In this paper, we discuss the influence of positive energetic habits and practices that help enhance performance and productivity levels. Hence, this is a theoretical exploration—the inquiry involving human potential development at the core the prospect of which relates to broad organisational goals designed to assist workers and workforces to achieve their maximum potential.

3. The Metaphysical Basis of Productivity

To understand the full import of the metaphysics of productivity, knowledge, nature, and being—according to Immanuel Kant (Lord, 2003), we may need to go back to the realms of theoretical reasoning which is highly abstract for rational examination of concepts about knowing and doing. As it involves thinking and action, so it must engage the intellect using which we can explain the metaphysical basis of the necessity of being productive. But there is one factor which need be considered as well: necessity. This is not about the question of existence of a single method or process—but an entire “product” which is brought into existence by the power of productive endeavors. But what about the reasons of being productive, of about the existence of a product? The reason for existence of a product lies in understanding the true essence of being—the principles of “utility”, “expediency”, and “value” (Viner, 1925). However, to prove its “essence” on the basis of utility—, i.e., the purpose of being productive, it would be impertinent to provide an explanation of its origin contingent upon the concept of utility, that is, if we can explain, by virtue of usefulness, the necessity of existence of certain products, or the necessity of being productive it would explain the very necessity of existence of the same product.

The metaphysical aspects of productivity examines the true essence of being productive, i.e., what it means to be productive. Further on, how productivity should be defined and pursued? Great scientists and highly creative individuals constitute perfect examples of highly productive beings. Specially, scientists are known for their great patience as they persuade themselves in trying to obtain results, and they keep trying, often to extreme levels, by persevering hard to attain their objectives. They search for effects, and they also seek to identify the factors that cause the effect. This makes them productive. Besides, the metaphysical aspects also help us examine the relationship between individual efforts, aptitude, resources, and the creation of value. Here, productivity is measured as a quantifiable variable: measured as output per unit of input.

Because productivity is the key driver of economic and social growth and competitiveness, it is generally defined in terms of the ability to organise and utilise resources and technology to achieve maximum efficiency and output. In such respect, it is defined as productive capacity, which means the potential of a system to produce goods and services. It is this potential which is the essence of productivity. It makes something or somebody productive. Now, the principal components of individual productiveness could be defined as productive capacity, which include skills, knowledge, experience, and abilities. The social aspects of productivity relates to individuals who cooperate with others in groups to achieve collective or organisational goals. This cooperation leads to coordination, which drives the economy and makes a society productive with marketable goods and services which it has to offer.

However, the metaphysical aspects look into things that are beyond simple metrics and measurements of productivity. As it is evident that our relentless pursuit of productivity has raised many question and problems for the very society in which we dwell, we are now facing sustainability issues that are challenging the environment and ecosystem, or both. Hence, it is necessary to balance economic productivity with human values, welfare, and wellbeing being the principal components of a sustainable society. Therefore, the metaphysics of productivity urges us to look beyond simple numbers or measures of productivity, and to consider social, ecological, and environmental factors of wellbeing into account.

4. The Market Economics of Productivity

What explains the economics of productivity (Jorgenson, 2009), and what factors contribute to the development of market power? The necessity existence of a product arises from the supposed utility of a proposed product or a service that would most likely serve some purpose, fulfil the needs or wants of consumers, and satisfy certain norms of expectations (Bernard, Redding & Schott, 2009). Of course, very few can match the productivity level of an individual expert who’s a top performer or an industry trailblazer who excels in production of high quality consumer goods. These entities become glaring examples of productivity that strongly establishes mutual connections between producers and consumers. Now, let us explain the productive power by a simple linear equation as follows:

In the above

equation 1, productive power (

) is determined by several factors including market forces (

) and ‘

’ number of consumers. The variable

denotes productivity rate, whereas

signify a constant term. A useful reminder: market economies are adjusted to produce optimal goods (

) for consumption by utilising an “optimal amount” available means (capital, human resources, noetic assets) that are relatively scarce.

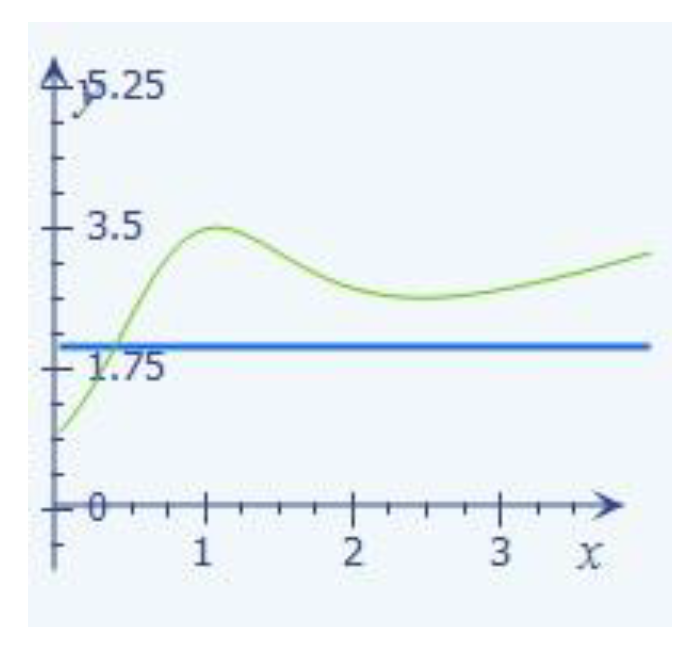

Figure 2 below depicts the production function equation which partially explains the market power of productivity.

The productive power of an economy is demonstrated by the core sectors that actually produce goods and services, and these constitute firms (Loecker & Biesebroeck, 2016). Similarly, productive individuals through their acts of productivity become models of excellence. All these entities are discrete parts of the whole economy, connected by the economic functions of demand and supply, who fight for limited means (resources) to attend desirable ends. The market economics of productivity is the result of the dynamic interplay of all the factors of productivity characteristic of a free market in which producers, sellers, buyers, and consumers get themselves engaged in their routine activities. At the individual level, however, individuals using the power of productive capability create niche space for themselves, and often set great examples before people. They, too, contribute towards creation of market power, although not in a grand scale like the scale economies, i.e., large firms who control the markets and exercise a certain degree of market power (Klette, 1999).

For many individuals, routine action of learning is a duty, as for most students, it is a norm and practice. As for example, in organisational settings, strategic management experts who are fast learners as well, continuously experiment and develop novel, more effective, and productive theories of learning. These are incorporated as practical engagements for the workforces, which serve different organisational purposes, i.e., productivity enhancement, marketing innovation, powering creativity, etc. Strategic managers can use the wisdom of learning (besides productive wisdom) to examine and sort out productivity failure, identify causes of diminishing returns, or deal effectively with practical inefficiencies constraining organisational operations. A deep analysis of the context helps in identifying the constraining factors hitherto gone undetected. And, it must involve the noetic machineries of the mind. A similar analogy becomes useful when:

“The intellect applied to the deep study of a book generates as many [new] ‘ideas’.”

Hence, by knowing the cause and being the basis of actions, wisdom can be gained, as it helps organisational experts go a long way in inspiring growth, productivity and performance among the employees. It promotes a positive, productive environment supportive of successful endeavors. It also promotes productive propagation of constructive ideas and precepts. This explains the metaphysics of productivity for success, which is the sole “motto” of productive market economics.

5. Conclusions

The research explains the productive power of markets in the light of the economics of productivity. The metaphysical basis of productivity and productive market power has been briefly examined, which brings forth important knowledge about the dynamic interactions of market forces that constitute the basis of market power (Hall, 1986). Further research is called for to explain in detail the economics of productive market power and to understand the intricate mechanisms that generate power in markets—the agents being producers, sellers, marketers, and buyers. Their dynamic interplay and interactions among them form the basis of productive market power.

Acknowledgements

The author extends his gratitude to the V.S. Krishna Central Library, Andhra University for providing access to conduct this research.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are exclusively of the author and do not represent the views of the QNM Lab or Andhra University, or any other entity. This is only a theoretical research and in no way involve any use of animal or human subjects.

| 1 |

See, for instance, Baier, S. L., Dwyer Jr, G. P., & Tamura, R. (2006), How important are capital and total factor productivity for economic growth? Economic Inquiry, 44, 23-49. |

References

- Baier, S. L. , Dwyer Jr, G. P., & Tamura, R. How important are capital and total factor productivity for economic growth?. Economic Inquiry, 2006, 44, 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, A. B. , Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. Products and productivity. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 2009, 111, 681–709. [Google Scholar]

- Comin, D. Total factor productivity. In Economic growth (pp. 260-263). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010.

- Danlami, I. A. , Hidthiir, M. H., & Hassan, S. Determinants of productivity: a conceptual review of economic and social factors. Journal of Business Management and Accounting, 2018, 8, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- De Loecker, J. , & Van Biesebroeck, J. 2016. Effect of international competition on firm productivity and market power (No. w21994). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Eichler, M. , Grass, M., Blöchliger, H., & Ott, H. Determinants of productivity growth. BAK Report, 2006, 1.

- Fried, H. O. , Schmidt, S. S., & Lovell, C. K. (Eds.). The measurement of productive efficiency: techniques and applications. Oxford university press, 1993.

- Hall, Robert E. 1986, “Market Structure and Macroeconomic Fluctuations”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, pp. 285-338.

- Jorgenson, Dale W., ed. The Economics of Productivity. International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, Vol. 236. Elgar, 2009.

- Klette, T. J. Market power, scale economies and productivity: estimates from a panel of establishment data. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 1999, 47, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L. , & Kagioglou, M. On the metaphysics of production, 2005.

- Koskela, L. , & Kagioglou, M. On the metaphysics of management. IGLC, 2006.

- Levinsohn, J. , & Melitz, M. Productivity in a differentiated products market equilibrium. Unpublished manuscript, 2002, 9, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, B. Kant’s productive ontology: knowledge, nature and the meaning of being (Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick), 2003.

- Morrison, C. J. Market power, economic profitability and productivity growth measurement: An integrated structural approach, 1990.

- Soysal, G. P. , & Krishnamurthi, L. Demand dynamics in the seasonal goods industry: An empirical analysis. Marketing Science, 2012, 31, 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T. General equilibrium analysis of production and increasing returns (Vol. 4). World Scientific, 2009.

- Syverson, C. What determines productivity? . Journal of Economic literature, 2011, 49, 326–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).