1. Introduction

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is a prevalent neuromuscular disorder primarily affecting type 2 diabetic patients. Elevated blood glucose levels contribute to nerve damage, leading to reduced sensation, mainly in the lower limbs [

1,

2,

3,

4] . Common symptoms include tingling, numbness, burning sensation under the feet, and pain in the lower extremity muscles. In 2019, DPN affected over 422 million individuals globally, with an estimated prevalence of peripheral neuropathy exceeding 70% in type 2 diabetes patients [

5,

6]. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports a current diabetes mellitus prevalence of 12% in the United States, up from 10% in previous years. If present trends continue, it is estimated that 1 in 3 Americans will have diabetes by 2050 due to escalating obesity rates and sedentary lifestyles [

29,

30]. DPN represents a late complication of type 2 diabetes, progressively impacting lower limb muscles and impairing functional capacity, thus increasing the risk of falls [

7]. Investigating postural control mechanisms in DPN patients is significant for mitigating fall risk.

Balance impairment is prevalent among patients with DPN, resulting in altered gait patterns and movement deficits because of DPN associated pain and sensory deficits. Compared to individuals without DPN, those with DPN are at a significantly higher risk of falls due to postural balance deficits[

1,

2,

3,

8,

9,

10]. Falls pose a considerable health concern, particularly among elderly patients with DPN [

7,

11,

12,

13]. Studies have consistently highlighted sensorimotor deficits in DPN patients, contributing to postural and gait instability[

7,

14,

15]. Reduced sensorimotor function in the lower extremities is strongly associated with increased falls in the elderly population [

16]. DPN patients are up to 20-fold more likely to fall compared to an age-matched non-diabetic control [

31]. Consequently, elderly patients with DPN often adapt their walking pace that exhibits larger gait variability, indicative of unstable walking [

17]. These findings support the perception that DPN patients may face challenges in maintaining postural control during gait. Investigating the gait in DPN patients may elucidate the mechanisms behind impaired postural control offers potential for early detection of DPN and associated fall risks in patients with DPN and related neuromuscular disorders.

Assessment of postural control in this study encompassed both static balance (stance) and dynamic postural control during gait. Static balance was evaluated via tandem stance, and dynamic postural control was assessed during walking using the modified Time-to-contact (TTC) method. Increased Center of Pressure (COP) displacement during static standing typically correlates with compromised balance and elevated fall risk. Although previous research has explored postural control in individuals with DPN during quiet and single-leg standing, indicating poorer performance and greater COP excursions compared to healthy controls [

18], it remains unclear whether these individuals exhibit altered postural control during dynamic activities such as walking. Therefore, further investigation into postural control under dynamic conditions, such as walking, among DPN patients may offer valuable insights into gait efficiency and fall risks.

Time-to-contact (TTC), also referred to as time-to-boundary, serves as a measure for assessing postural stability [

19,

20]. TTC estimates the time required for the COP to reach the boundary of the foot [

19], encompassing both spatial and temporal aspects of postural control including velocity and acceleration relative to the base of support [

20]. To address challenges in applying standard TTC analysis to dynamic activities like walking, a modified TTC method has been proposed. This modification accounts for the necessity of COP transitioning from one foot boundary to another as the body moves forward during gait, thus enabling assessment of postural adjustments important for maintaining balance and stability while walking. Previous studies have investigated postural stability in DPN patients under static conditions, such as quiet standing and single limb stance, with eyes open and closed [

18,

21,

22]. However, there is a lack of research specifically examining dynamic postural stability, which involves maintaining balance during routine activities such as walking. Another study focused on standard TTC analysis during quiet standing [

18]; however, the modified TTC method permits evaluation of postural stability during gait. This modified TTC approach proved effective in assessing postural stability in patients with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) during walking [

23]. Therefore, this innovative TTC approach holds great significance for investigating postural control mechanisms in individuals with DPN during walking.

The objective of this study is to analyze gait and postural control mechanisms under both static and dynamic conditions in DPN patients, in comparison to age and gender matched healthy controls. This is achieved through a series of trials designed to assess functional mobility, static and dynamic balance, gait parameters (e.g., velocity, step length, stride length, phase durations) were analyzed during walking trials. Static balance was assessed using the tandem stance test (eyes open/closed), dynamic postural control during gait, and mobility through the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. Group comparisons were performed using statistical analysis. Our hypothesis suggests that during the single-support phase of walking, DPN patients may exhibit decreased ML TTC percentage, ML COP excursion, and ML COP velocity compared to their healthy counterparts. These alterations are indicative of compromised postural stability mechanisms and are likely to contribute to impaired balance control and decreased functional mobility in the DPN population.

2. Method

Participants Participants aged between 40 and 75 were recruited from Little Rock Walk-In Clinic in Little Rock, Arkansas, USA, under the supervision of an endocrinologist and medical doctor. Fifteen individuals diagnosed with DPN agreed to take part in the study (see

Table 1). Inclusion criteria comprised: 1) a minimum 7-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, 2) hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels equal to or greater than 7, 3) absence of other comorbidities impacting pain and function, 4) BMI below 35, and 5) no prior history of falls, capable of walking 10 meters unaided. Participants with DPN reported engaging in regular light-to-moderate physical activities such as daily walking and playing tennis. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) approved the study, with all participants providing written informed consent. Fifteen healthy controls, matched for age, gender, and BMI, were recruited to compare with the 15 DPN patients (see

Table 1). Control participants were sourced through flyers, emails, and word of mouth, all recruited between July 2021 and October 2021. The control participants were free of any pathological conditions hindering unassisted walking.

Experimental Procedures Three-dimensional kinematic data was collected using 10 cameras (Vicon, Oxford, UK) operated at 100 Hz. Twelve markers were placed on both feet: bilateral great toe, heel, medial midfoot, lateral midfoot, medial malleolus, and lateral malleolus. Four force platforms (at UAMS; dimension: 40 cm × 60 cm; AMTI, Watertown, MA) or one force platform (at UALR; dimension: 60cm × 90 cm; AMTI, Watertown, MA) were used to collect force and COP data operating at 1000 Hz (

Figure 1). Video and force platform data were synchronized using Vicon Nexus (Vicon, Oxford, UK). The participants were instructed to 1) perform a tandem balance stance with eyes open and eyes closed for a period of 20 seconds and 2) walk on a 10-meter walkway at their preferred pace, until three trials of complete data were captured where at least three-foot contacts within the borders of the four force platforms was required for a trial to be deemed complete.

3. Data Processing

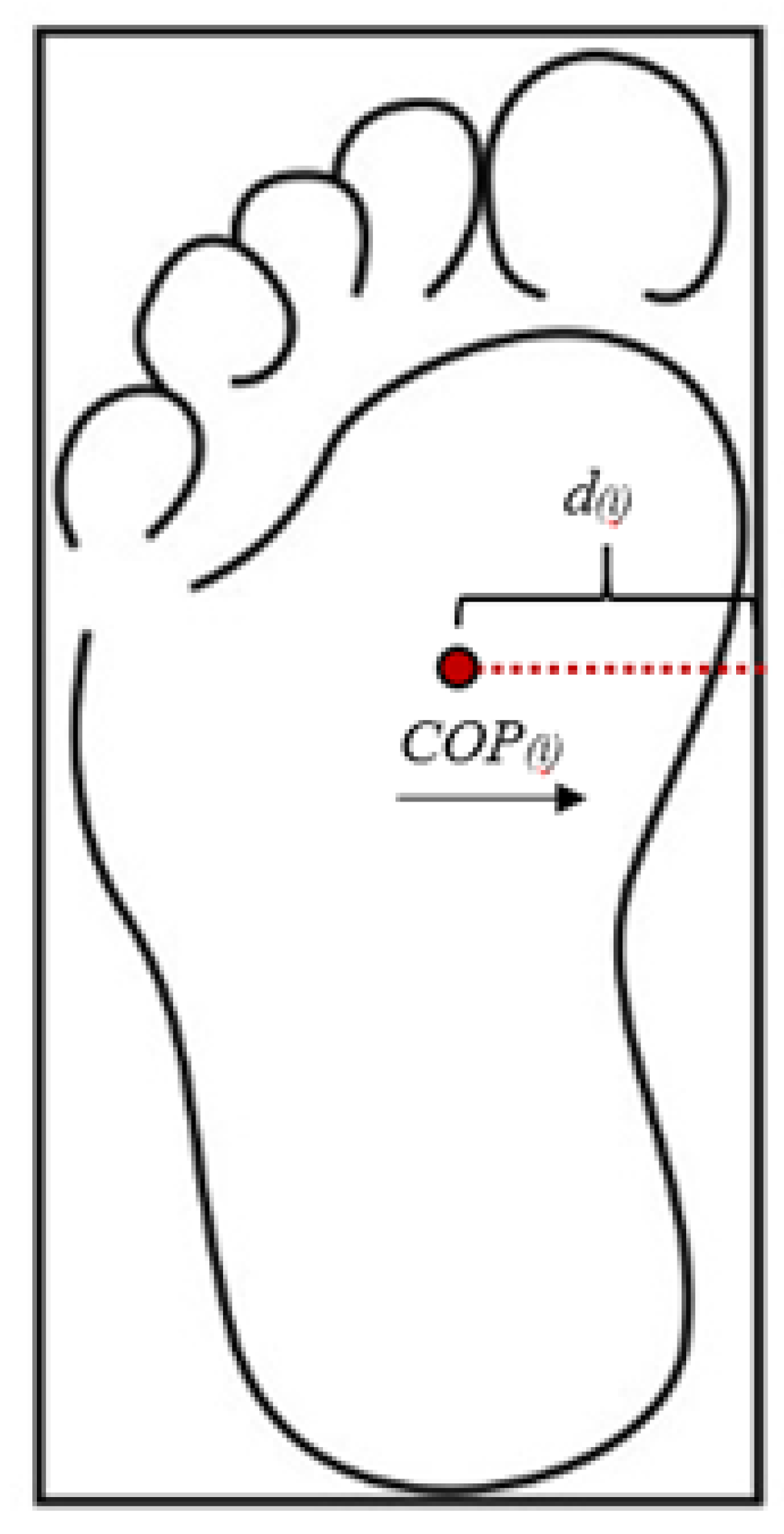

The time-to-failure during tandem balance stance and time to complete time up and go test was recorded using a stopwatch. Gait parameters were extracted from the time-series data by identifying distinct events (e.g., heel strike and toe off) and measuring the temporal and spatial intervals between them. Single stance and double stance phases were identified using the vertical ground reaction forces and toe velocities. Toe velocities were utilized to determine gait events for the contralateral limb due to either a limited number of force plates or off-foot contact within the force platform. The double stance ratio was computed as the ratio of double stance time to single stance time. COP excursions and mean COP velocities in both the Anterior-Posterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) directions were assessed during single stance phases for each foot. COP velocities and accelerations were calculated using the first central difference method. Rectangular boundaries for each foot (see

Figure 2) were defined using the heel, toe, medial midfoot, and lateral midfoot markers.

Since the COP shifts between the boundaries of each foot during walking, a modified version of TTC was utilized [

24,

25,

26]. The ML COP positions, velocities, and accelerations were incorporated into Equation (

1) to compute the ML time-to-contact (TTC). COP velocity and acceleration were calculated using the first central difference method.

: distance from COP to ML boundary

: ML COP velocity

: ML COP acceleration

i : each data point (100 Hz)

TTC was calculated at each data point and then compared to the remaining single stance time. If the TTC was less than the remaining single stance time, then the TTC value was stored for that time point, indicating a postural adjustment was required during single stance. TTC percentage was then calculated by dividing average TTC during single stance by one-half of single stance time. Thus, a TTC percentage of 100% indicated that no postural adjustment was required during single stance. The mean ML COP trace was determined during single stance phase and then normalized to ML boundaries (

Figure 2). By normalizing ML COP traces and computing TTC percentages, this novel approach facilitates the identification of balance impairments, offering insights into dynamic balance control mechanisms during walking.

Statistical Analysis There were seven dependent variables: double stance ratio, AP and ML COP excursions, mean AP and ML COP velocities, AP and ML TTC percentages. Double stance ratio and COP-based parameters were calculated using custom MATLAB code (MathWorks Inc., Natik, MA). We hypothesized that individuals with DPN would demonstrate reduced mediolateral TTC percentage, COP excursion, and COP velocity during single-support walking, as well as impaired static balance control, compared to healthy controls. Unpaired t-tests were performed where appropriate using the SPSS statistical package (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). For comparisons of statistical significance, Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated and interpreted as follows[

27]: 0.20-0.49 = small effect; 0.50-0.79 = medium effect and

large effect. The level of statistical significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

Postural control was quantified using several key measures. COP excursion represents the total movement of the COP, reflecting the magnitude of postural sway. COP velocity is the average speed of COP movement, indicating how quickly balance adjustments are made. TTC percentage expresses how much of the available single-stance time remains before the COP reaches the edge of the base of support, normalized to one-half of single-stance duration. COP trace describes the normalized mediolateral COP path within the foot boundaries during single stance. Together, these measures capture both the magnitude and timing of balance adjustments.

No significant differences were found in postural control parameters between DPN patients and healthy controls during dynamic walking conditions. Specifically, there were small differences in double stance ratio (5.7%; p=0.523), AP COP excursion (-5.6%; p=0.541), ML COP excursion (11.8%; p=0.687), AP COP velocity (-5.6%; p=0.381), AP TTC (1.9%; p=0.665), ML TTC (2.7%; p=0.442), ML COP velocity (-1.4%; p=0.917), or ML COP trace (-2.1%; p=0.724). However, significant differences in gait characteristics were observed. DPN patients demonstrated significantly slower gait velocity (-26%; p < 0.001) and shorter step length (-11%; p = 0.035) compared to healthy controls. In contrast, stride length (-34%; p < 0.001) was shorter, while the duration of stance phase (+33%; p < 0.001), and duration of stride (+34%; p < 0.001) were significantly longer in DPN patients compared to healthy controls (

Table 1).

The static balance control was assessed using the tandem balance stance test, performed for 20 seconds with both eyes open and closed. DPN patients demonstrated significantly poorer static balance control compared to healthy controls under both conditions. Specifically, DPN patients had a shorter time to failure under the eyes open condition (9.21 s vs. 20.0 s; p = 0.008) and even more pronounced deterioration under the eyes closed condition (4.27 s vs. 18.26 s; p = 0.004). These findings indicate that DPN patients experience significant balance deficits, particularly when visual feedback is removed (

Table 2). Furthermore, mobility was assessed using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, where DPN patients were significantly slower to complete the task compared to healthy controls (17.81 s vs. 11.45 s; p = 0.001) (

Table 3).

In summary, while no significant differences were found in postural control during dynamic walking, significant differences were observed in gait parameters, static balance control, and mobility measures. DPN patients exhibited slower gait velocity, shorter step length, as well as longer stride length, stance duration, and stride duration compared to healthy controls. The static balance control was significantly impaired in DPN patients under both eyes open and eyes closed conditions, with a significant reduction in the time to failure on the tandem balance stance test. DPN patients also demonstrated slower performance on the TUG test compared to healthy controls.

5. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate gait characteristics and postural control in patients with DPN compared to age- and gender-matched healthy controls. While we initially hypothesized that DPN patients would exhibit significant gait alterations due to dynamic balance control deficits resulting from nerve damage and muscle weakness, our findings were more nuanced. We observed no significant differences in key postural control measures, such as double stance ratio, COP excursion (both anterior-posterior and medial-lateral), and COP velocity between DPN patients and healthy controls. However, despite the absence of postural control differences, DPN patients demonstrated several gait alterations, including slower cadence and step length, as well as smaller stride length, longer stance duration, and longer stride duration. These results suggest that DPN patients may adopt compensatory strategies in their gait to maintain postural stability, despite the sensory deficits associated with neuropathy.

While the active lifestyle and relatively healthy body composition of our DPN cohort may explain the relatively mild gait alterations observed, these findings also underscore the complexity of DPN and its impact on movement. The DPN patients in this study were not significantly overweight or obese, though they were not free from excess weight either. As a result, while their weight may not have contributed substantially to the observed gait differences, it may still have played a role in the subtle compensations we observed. Importantly, these patients were physically active, regularly participating in sports and exercise routines, which likely helped preserve neuromuscular function and balance, mitigating the more severe gait disturbances that can be seen in sedentary DPN patients or those with other comorbidities such as obesity. Our findings thus highlight the important role of physical activity and good physique management in maintaining gait function and balance in individuals with DPN.

Despite the relatively mild gait alterations, we did observe significant balance deficits in DPN patients under static conditions. In the tandem balance stance test, which was performed for 20 seconds with both eyes open and closed, DPN patients demonstrated significantly poorer balance compared to healthy controls. This finding was particularly pronounced under the eyes closed condition, where reliance on proprioception is heightened. The absence of significant differences in dynamic postural control may reflect compensatory adaptations during walking, such as slower gait speed, increased stance duration, and greater reliance on visual input. Static balance tasks, lacking momentum and continuous gait-based sensory updates, may expose deficits that dynamic movement can mask. The deterioration in balance under eyes closed conditions may reflect the extent of sensory loss and the challenges DPN patients face in relying on their remaining sensory systems (e.g., vestibular input and vision) to maintain stability.

In addition to balance testing, we also assessed mobility using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. As expected, DPN patients were significantly slower to complete the TUG task compared to healthy controls. This finding aligns with previous studies, which have shown that DPN patients often exhibit slower mobility due to both sensory deficits and reduced muscle strength, making it more difficult to perform tasks that require rapid postural adjustments and coordination [

31,

32,

33] The slower performance on the TUG test in our cohort further emphasizes the impact of DPN on functional mobility, even in patients who engage in regular physical activity. While they may compensate for some gait deficits during walking, the additional demands of rapid movement and postural control in functional tasks like the TUG test reveal the underlying mobility impairments in this population.

Although our DPN cohort demonstrated compensatory adaptations in their gait, such as slower gait and increased stance duration, the balance deficits observed under static conditions and slower mobility on functional tasks indicate that the neuropathy still exerts a significant impact on overall balance and function. The lack of significant differences in postural control measures like COP excursion and velocity could be explained by the fact that these patients may rely more heavily on compensatory strategies (such as slower movements and increased reliance on visual inputs) to stabilize their center of pressure during dynamic gait tasks. The absence of marked differences in these dynamic measures suggests that, while DPN patients may not exhibit visible postural control deficits, their ability to adjust their posture efficiently during walking is still impaired by the underlying neuropathy.

These findings highlight the complexity of DPN and its effects on movement. While the physical activity levels of our cohort appear to have mitigated some of the more severe gait and postural control deficits typically seen in DPN patients, their performance on balance and mobility tests clearly shows that they still face challenges. The results suggest that regular physical activity, which likely enhanced strength, coordination, and proprioception, plays a critical role in minimizing the functional deficits associated with DPN. However, despite these compensations, DPN patients remain vulnerable to balance and mobility impairments, particularly in situations requiring quick postural adjustments or when visual feedback is limited.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size (15 DPN patients vs. 15 healthy controls), which may reduce the statistical power to detect smaller differences in gait and postural control. Additionally, while we controlled for age and gender, we did not match for other potential confounders, such as specific comorbidities or detailed measures of neuropathy severity. Further studies with larger, more diverse cohorts, including individuals with varying levels of DPN severity and different activity levels, are needed to better understand the full impact of physical activity on gait and balance in DPN patients.

6. Conclusion

DPN patients in this study demonstrated compensatory gait adaptations and maintained similar postural control patterns to healthy controls in dynamic conditions, they exhibited significant balance deficits in static conditions and slower mobility during functional tasks. These findings highlight the importance of physical activity in managing the functional impairments associated with DPN, yet also underscore the challenges that remain, particularly in tasks requiring rapid adjustments and in static balance conditions. Future research should explore interventions that could further improve balance and mobility in DPN patients, with a particular focus on enhancing proprioceptive feedback and postural control strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.U. and K.I.; methodology, S.U.; software, S.U.; validation, S.U., K.I.; formal analysis, S.U.; investigation, S.U.; resources, S.U. and K.I.; data curation, S.U.; writing-original draft preparation, S.U.; writing-review and editing, S.U., K.I. and M.R.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, K.I.; project administration, K.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Arkansas at Little Rock (Protocol number 21-012-R3) and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) and controlled subjects to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants for their contribution to this study. We also acknowledge the Department of Orthopaedics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences for access to the Orthopaedics Biomechanics Research Laboratory, and Dr. Junsig Wang, then Assistant Professor and laboratory supervisor, for his guidance in data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| l]@ll

AMTI |

Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc. |

| AP |

Anterior-Posterior |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| COP |

Center of Pressure |

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| DPN |

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin Test |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| ML |

Mediolateral |

| PTTD |

Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction |

| TTC |

Time To Contact |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go |

| UALR |

University of Arkansas at Little Rock |

| UAMS |

niversity of Arkansas for Medical Sciences |

References

- Bansal, V.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U. K. Diabetic neuropathy. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2006, 82(964), 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinninger, G. M.; Vincent, A. M.; Feldman, E. L. The role of growth factors in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System 2004, 9(1), 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinik, A. I.; Strotmeyer, E. S. Diabetic Neuropathy. In Pathy’s Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine, 5th ed; Wiley, 2012; Vol. 1, pp. 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lazzarini, P. A.; Mcphail, S. M.; Van Netten, J. J.; Armstrong, D. G.; Pacella, R. E. Global Disability Burdens of Extremity Complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C. W.; Selvin, E. Epidemiology of Peripheral Neuropathy and Lower Extremity Disease in Diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports 2019, 19(10), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustapa, A.; Justine, M.; Mohd Mustafah, N.; Jamil, N.; Manaf, H. Postural Control and Gait Performance in the Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review. BioMed Research International 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balducci, G.; Sacchetti, M.; Haxhi, J.; Orlando, G.; D’Errico, V.; Fallucca, S.; Menini, S.; Pugliese, G. Physical exercise as therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2014, 30(S1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawacha, Z.; Gabriella, G.; Cristoferi, G.; Guiotto, A.; Avogaro, A.; Cobelli, C. Diabetic gait and posture abnormalities: A biomechanical investigation through three dimensional gait analysis. Clinical Biomechanics 2009, 24(9), 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. W.; Hsu, W. C.; Lu, T. W.; Chen, H. L.; Liu, H. C. Patients with type II diabetes mellitus display reduced toe-obstacle clearance with altered gait patterns during obstacle-crossing. Gait & Posture 2010, 31(1), 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, S. D.; Pohl, P. S.; Mahnken, J. D.; Kluding, P. M. Diagnostic accuracy of fall risk assessment tools in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Physical Therapy 2012, 92(11), 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, R. M. W.; Ng, T. K. W.; Kwan, R. L. C.; Choi, C. H.; Cheing, G. L. Y. Risk of fall for people with diabetes. Disability and Rehabilitation 2013, 35(23), 1975–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriveau, H.; Hébert, R.; Prince, F.; Rache, M. Postural control in the elderly: An analysis of test-retest and interrater reliability of the COP-COM variable. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2001, 82(1), 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanavati, T.; Shaterzadeh Yazdi, M. J.; Goharpey, S.; Arastoo, A. A. Functional balance in elderly with diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2012, 96(1), 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. I.; Chen, Y. R.; Liao, C. F.; Chou, C. W. Association between sensorimotor function and forward reach in patients with diabetes. Gait & Posture 2010, 32(4), 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A. V.; Hillier, T. A.; Sellmeyer, D. E.; Resnick, H. E. Older Women With Diabetes Have a Higher Risk of Falls. Diabetes Care 2002, 25(10), 1749–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman de Mettelinge, T.; Cambier, D.; Calders, P.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Delbaere, K. Understanding the Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Falls in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8(6), 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLiberto, F. E.; Nawoczenski, D. A.; Tome, J.; McKeon, P. O. Use of time-to-boundary to assess postural instability and predict functional mobility in people with diabetes mellitus and peripheral neuropathy. Gait & Posture 2021, 83, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobounov, S. M.; Moss, S. A.; Slobounova, E. S.; Newell, K. M. Aging and time to instability in posture. Journals of Gerontology - Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 1998, 53(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J. M.; Gagnon, J. L.; Hasson, C. J.; Van Emmerik, R. E. A.; Hamill, J. Evaluation of time-to-contact measures for assessing postural stability. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2006, 22(2), 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesian, H.; Farahpour, N.; Mazde, M.; Simoneau, M.; Turcot, K. Standing balance performance and knee extensors⇔ strength in diabetic patients with neuropathy. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2020, 36(3), 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corriveau, H.; Hébert, R.; Prince, F.; Raiche, M. Evaluation of postural stability in elderly with diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2000, 23(8), 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Latt, L. D.; Martin, R. D.; Mannen, E. M. Postural Control Differences between Patients with Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction and Healthy People during Gait. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.; Stevermer, C. A.; Gillette, J. C. Gait analysis post anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Knee osteoarthritis perspective. Gait & Posture 2012, 36(1), 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Carrying asymmetric loads during different walking conditions. Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University, 2016. Available online: https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/entities/publication/dc9b3a04-603c-40fa-b1d9-749455d1c312.

- Wang, J.; Gillette, J. C. Mediolateral postural stability when carrying asymmetric loads during stair negotiation. Applied Ergonomics 2020, 85, 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gillette, J. C. Carrying asymmetric loads while walking on an uneven surface. Gait & Posture 2018, 65, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhupathiraju, S. N.; Hu, F. B. Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circulation Research 2016, 118(11), 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.-A.; Alamian, A.; Onufrak, S. Public Health Research and Program Strategies for Diabetes Prevention and Management. Preventing Chronic Disease 2025, 22, 240501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, N. D.; Orlando, G.; Brown, S. J. Sensory-Motor Mechanisms Increasing Falls Risk in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Medicina 2021, 57(5), 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.; Nielsen, S.; Mogensen, C. E.; Jakobsen, J. Muscle Strength in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53(6), 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewston, P.; Deshpande, N. Falls and Balance Impairments in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Thinking Beyond Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 2016, 40(1), 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).