Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting.

2.2. Sample Size and Site

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Randomisation and Blinding

2.5. Mistletoe Therapy (Intervention Group)

2.6. Placebo (Control Group)

2.7. Data Collection

2.7.1. Recruitment

- Recruitment rate

- Obstacles to recruitment

2.7.2. Retention and Adherence

- Attrition rate with reasons if possible

- Acceptability of regular sub-cutaneous injections

- Adherence to the study therapy schedule

- Assessment of therapy related symptoms and health related quality of life in the sample population

- Completion of outcome measures

2.7.3. Blinding

- Assessment of blinding of patients

2.7.4. Adverse Events

- Adverse events from MT and placebo subcutaneous injections

2.8. Clinical Study Data

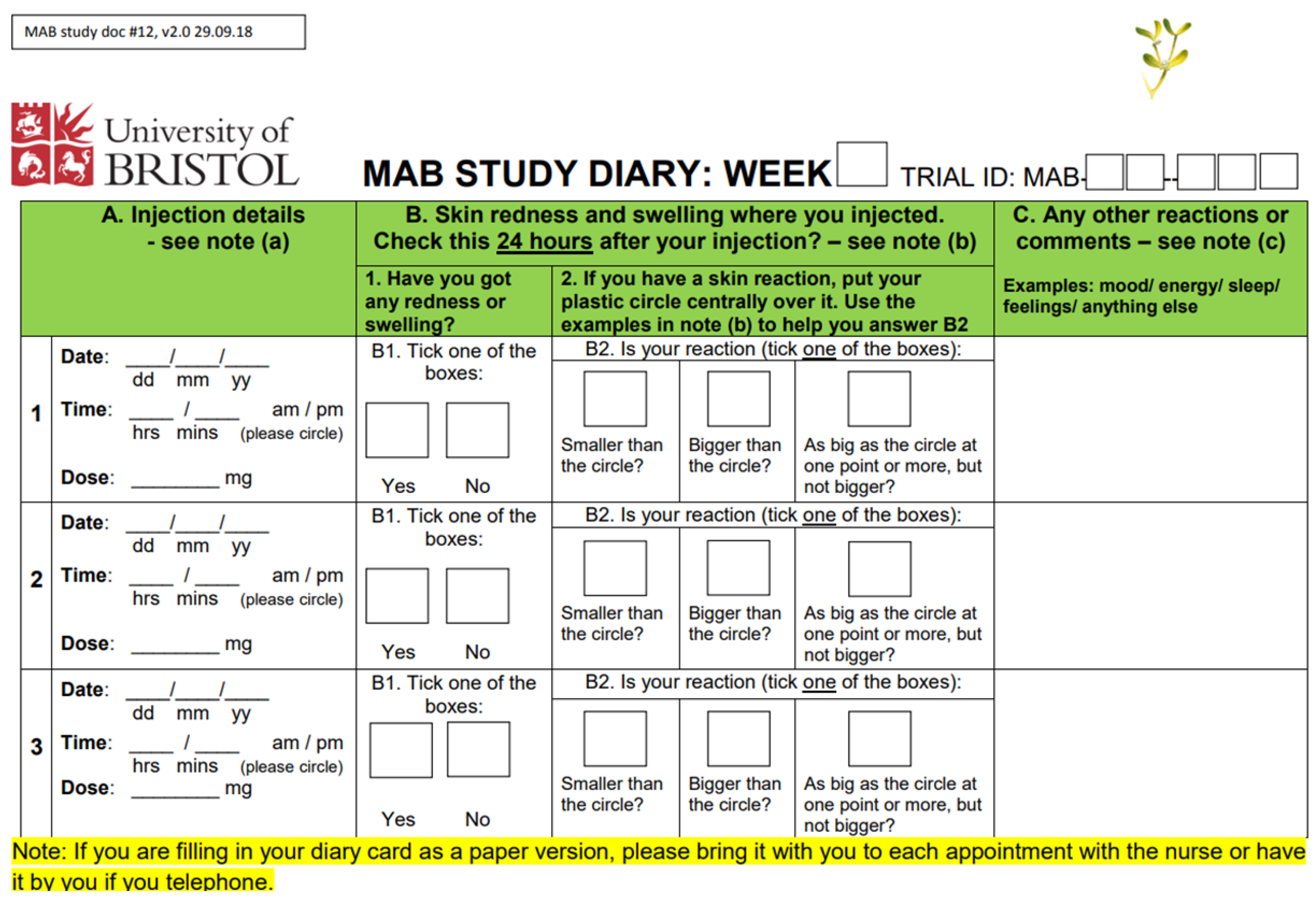

2.8.1. Participant Diaries

2.8.2. Questionnaire Pack

2.8.3. Adverse Events

2.8.4. Qualitative Interviews

2.9. Data Analysis

2.10. MAB Management

2.11. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

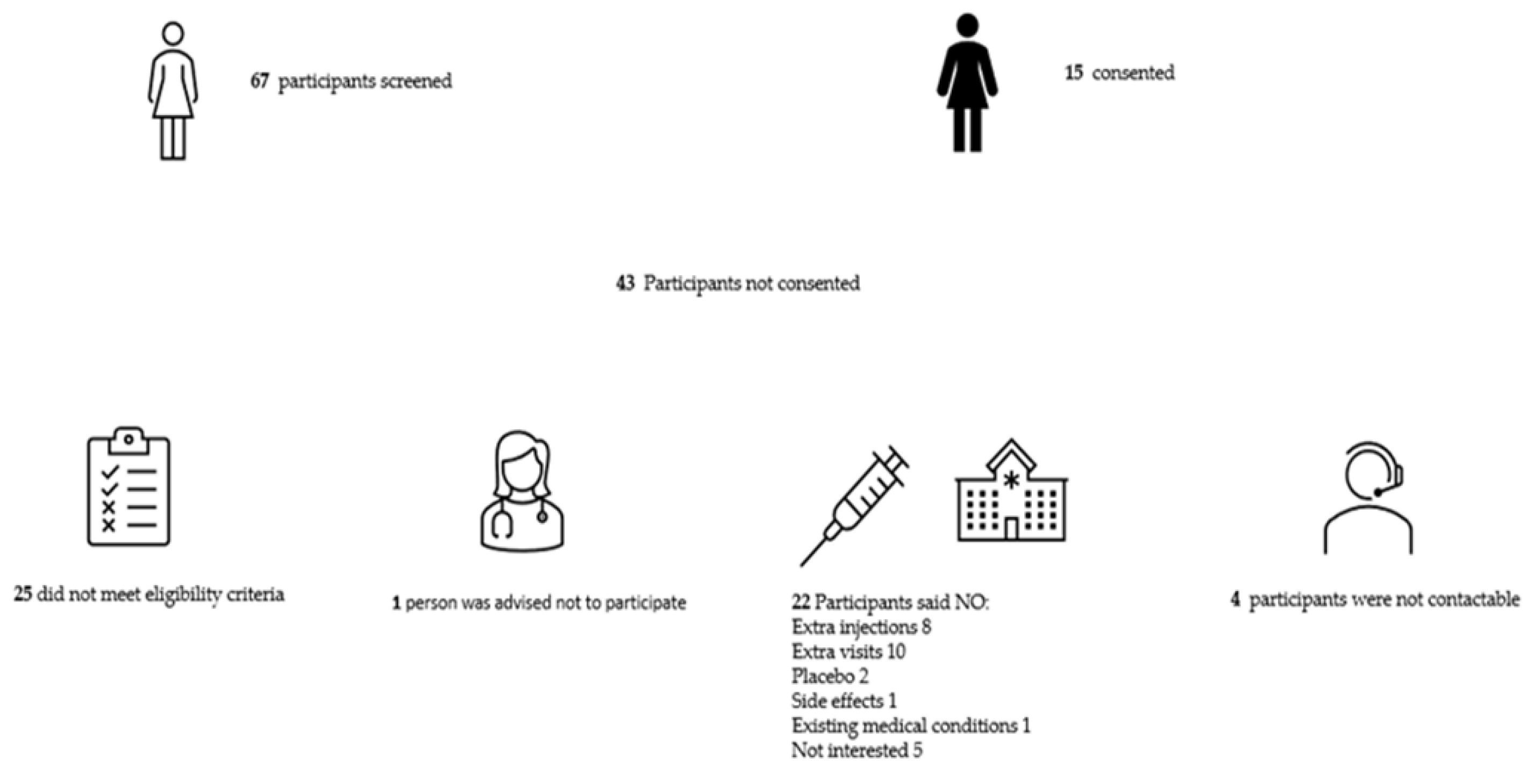

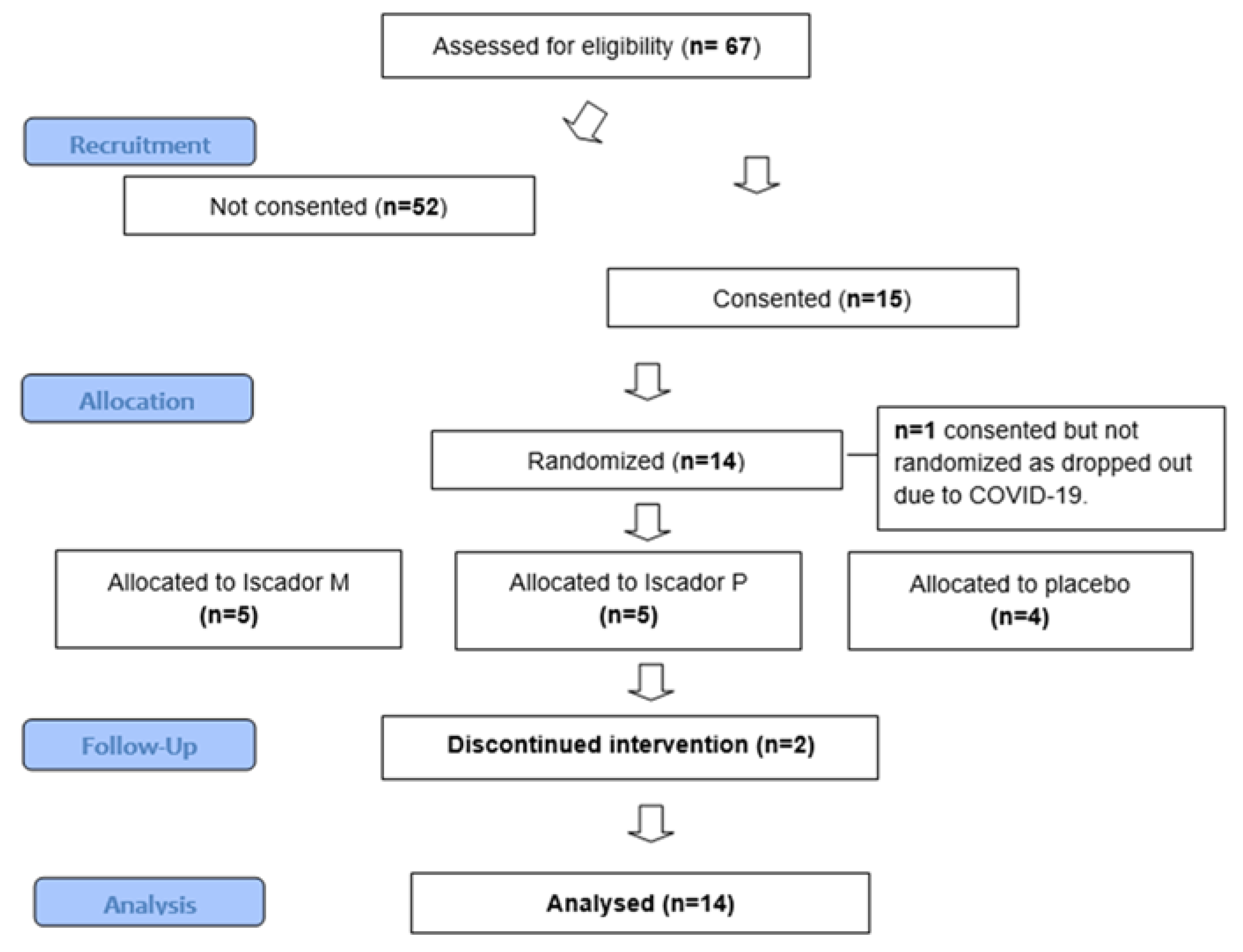

3.1. Recruitment

3.1.1. Barriers to Recruitment

3.1.2. Enablers to recruitment

3.2. Retention & adherence

3.2.1. Barriers to retention and adherence

3.2.2. Enablers to retention and adherence

3.3. Assessment of blinding

3.4. Adverse Events

3.5. Quality of Life Questionnaire

3.5.1. Acceptability

3.6. Outcome Data

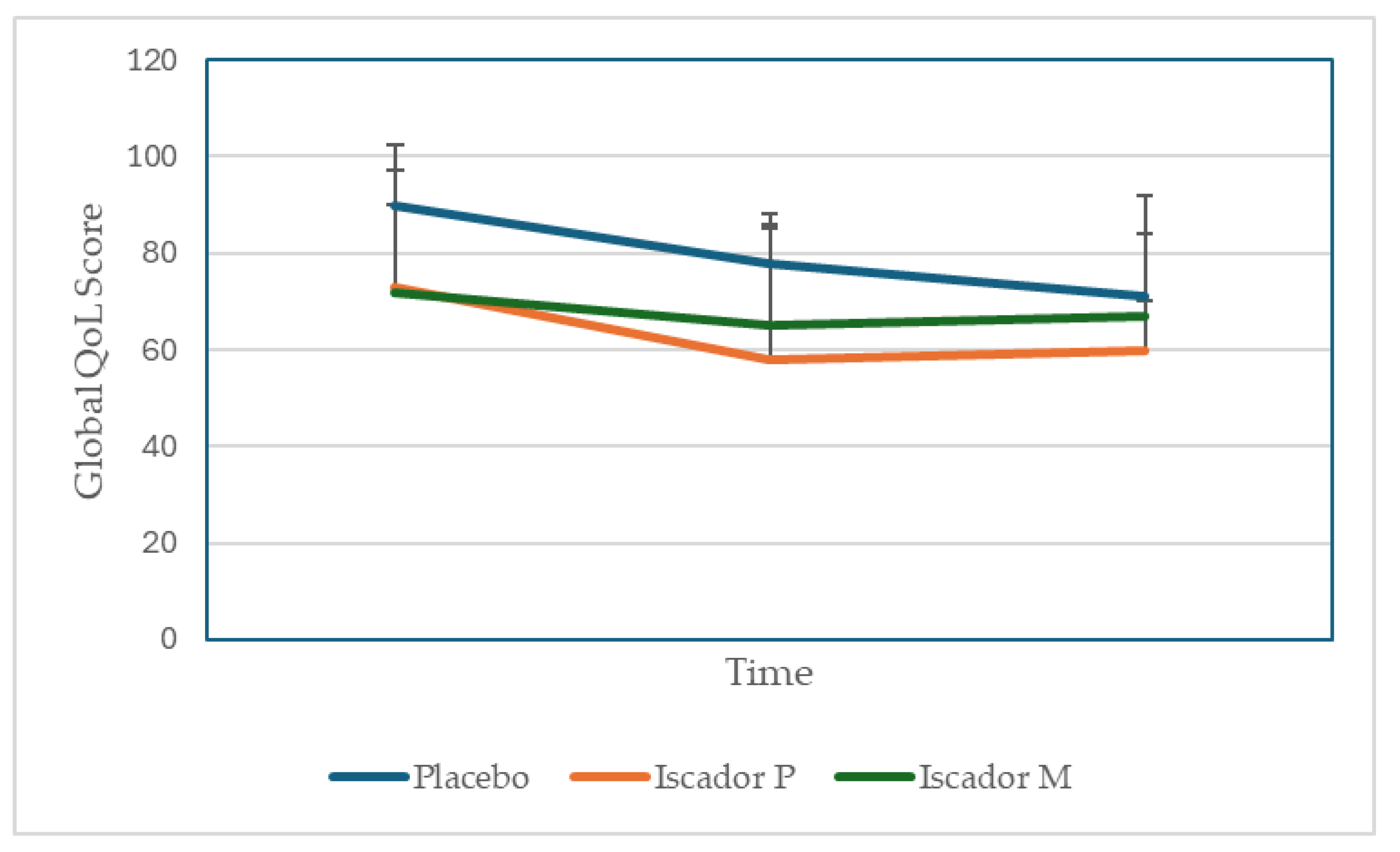

| Time /group | Placebo (n=4) | Iscador P (n=5) | Iscador M (n=5) |

| T0 | 90 ±12.5 | 78±24 | 71±18 |

| T1 | 73±8.0 | 58±27* | 60±23* |

| T2 | 72±20.9 | 65±10 | 67±17* |

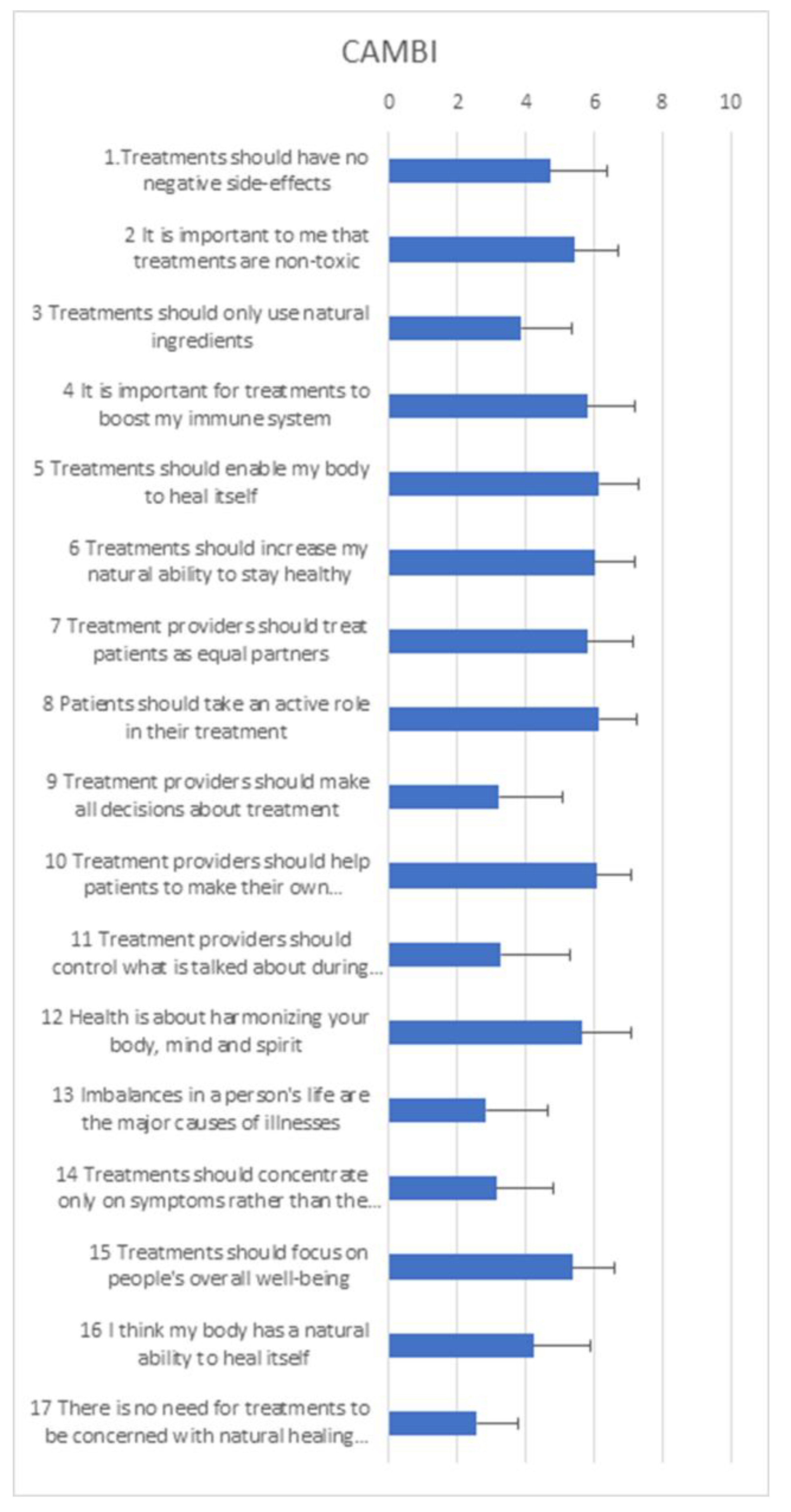

3.7. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Beliefs

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Strengths & Limitations

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the MAB Study

- Inclusion criteria

- a)

- Adults 18 years or over

- b)

- Histologically verified early or locally advanced invasive breast cancer (T1 – 3, N0 – 3, M0) without clinical suspicion/evidence of distant metastases. Routine staging for distant metastases should be according to local practice.

- c)

- Planned adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy regime

- d)

- Willing to self-administer or have a nominated person e.g., relative to administer

- subcutaneous injections

- e)

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1

- f)

- All other aspects of management as per the local multi-disciplinary team (MDT) decision.

- g)

- No active, uncontrolled infection

- h)

- Randomisation within 12 weeks of surgery

- i)

- Applicable to female participants only: non-pregnant and non-lactating, with no intention of pregnancy during chemotherapy, and prepared to adopt adequate contraceptive measures if pre-menopausal and sexually active. Adequate contraceptive measures according to the Clinical Trial Facilitation Group (CTFG) guidance for women of child-bearing potential (WOCBP)1 state that WOCBP can be recruited after a negative highly sensitive pregnancy test and assurance of an acceptable, effective method of contraception as a minimum until treatment discontinuation. Additional pregnancy testing should not be required.

- j)

- Applicable to male participants and relevant to trial therapy only, the participant should follow the guidance given by the nurse in relation to chemotherapy: No contraception measures are needed for male subjects with pregnant or non-pregnant women of childbearing potential as the Iscador product and placebo can be classified as having no genotoxicity or demonstrated or suspected human teratogenicity/fetotoxicity at subtherapeutic systemic exposure levels, as per the criteria set in the CTFG recommendations related to contraception and pregnancy testing in clinical trials.1

- k)

- No concomitant medical, psychiatric, or geographic problems that might prevent

- completion of therapy or follow-up.

- l)

- There will be no restrictions on MAB participants being involved in concurrent clinical trial as long as the consultant in charge of their care considers it appropriate and the study protocols do not exclude participation in more than one trial.

- Exclusion criteria

- a)

- Additional immunomodulatory therapy - for example: Patients receiving immunotherapy or biological therapy for autoimmune disorders, for diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory arthropathies, multiple sclerosis, etc.

- b)

- Receiving endocrine therapy as a stand-alone treatment

- c)

- Patients with known chronic viral infection such as active Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C or HIV

- d)

- Previous invasive breast cancer or bilateral breast cancer (unless treated with surgery or

- radiotherapy >5 years ago).

- e)

- Patients not able or willing to give informed consent

- f)

- Known allergy to mistletoe preparations

- g)

- Previous use of mistletoe, in the last 5 years, or current use of mistletoe

- h)

- Acute inflammatory or pyrexial conditions

- i)

- Chronic granulomatous diseases, active auto-immune diseases

- j)

- Hyperthyroidism with tachycardia.

- 1.http://www.hma.eu/fileadmin/dateien/Human_Medicines/01-AboutHMA/WorkingGro ups/CTFG/2014_09_HMA_CTFG_Contraception.pdf

Appendix B. MAB Study Therapy Regimes

- A)

- Example of typical study therapy & maintenance regime for both ISCADOR® M

- (Maleus) and ISCADOR® P (Pinus)

- Induction phase

- Week 1 0.01 mg (1.0ml) x3 = total of 0.03 mg Iscador M or P

- Week 2 0.1mg (1.0ml) x3 =total of 0.3 mg of Iscador M or P

- Week 3 1mg (1.0ml) x3= total of 3 mg of Iscador M or P

- Week 4 10mg (1.0ml) x3= total of 30 mg of Iscador M or P

- Week 5 20mg (1.0ml) x3= total of 60 mg of Iscador M or P

- Classification of reactions

- No or minimal response = no or only marginal local skin reactions, maximally 1 cm in diameter.

- Optimal response = local skin reactions, maximum diameter between 1 and 5 cm.

- Excessive response = local skin reactions, maximum diameter more than 5cm.

- A patient mistletoe medication was increased from the lowest dose to their optimal dose. The optimal dose was defined as a dose to which they experience a sustained local skin reaction, still present 24 hours after the injection. Such a reaction determines the dose they remained on for the rest of trial treatment unless they had a skin reaction of ≥5cm. In cases of skin reactions of ≥5cm, the participants dropped to the dose below (table 1) and this became their optimal dose.

- B)

- Treatment & maintenance regime with placebo

- Week 1-5

- Physiological saline 0.90% w/v of sodium chloride, (1.0ml) x3

- There is unlikely to be a sustained local reaction with the saline placebo and the participants will continue the same physiological saline preparation for the remaining time of the study but essentially the same rule applies as for the mistletoe arm: the participant would continue the same physiological saline preparation in week five and this will be called the maintenance dose.

Appendix C. MAB Participant Diary

Appendix D. Topic Guides for Qualitative Interviews with Participants

- Mistletoe And Breast Cancer (MAB) Pilot Trial: Participant interview topic guides (A and B)

- Interview A

- Patients who are participating in the study will be interviewed early in the study therapy phase. The interview will begin with general questions regarding their current health, how their [non-trial] treatment is going generally and how long they have been taking their study therapy. The following topics will then be explored:

- Previous knowledge and understanding of mistletoe.

- Before you were recruited into this trial had you heard of mistletoe therapy (also called Viscum, Iscador, Helixor etc)?

- If you had heard of it, what do you know about it? Did this match up with the information you have been given for the trial?

- If you hadn’t heard of it, what do you think about mistletoe therapy based on the trial information you have been given?

- Patients’ expectations of the study therapy

- What made you decide to join the MAB trial?

- What do you hope the trial therapy may do for you/help you with?

- Acceptability of consenting and randomisation procedures

- How did you feel about being asked to join the mistletoe trial (the process)?

- What did you think about the nurse’s approach – the information, signing a consent form?

- It will have been explained by the nurse that you may be randomised to one of two mistletoe therapies or placebo. How do you feel about possibly taking a placebo? - do you think that may change over time?

- Experiences and attitudes towards Complementary and Alternative therapies in general and herbal treatments specifically

- Mistletoe could be described as a CAM therapy. Talking more generally about CAM

- Have you used any herbal remedies or any other complementary therapies?

- How about family and friends?

- Which other remedies/ therapies? / For what reason? / What or who influenced you to use that? / Did you find it helpful?

- If you have not used CAM remedies/ therapies, have you ever thought about them, or about using them?

- Quality of life outcome measures & patient experience

- The participant will have filled in the questionnaires at the start of the therapy. It is also possible they may have filled in the mid-point questionnaire.

- Do the questions ask you about the issues/symptoms/effects that are experiencing or concerning/worrying/ you at this point?

- Are there some issues/ symptoms/ effects that you feel are missed out by the questions?

- Any questions which seemed irrelevant?

- Acceptability of questionnaires & patient diary

- How do you feel generally about filling in the questionnaires?

- Prompts:

- Usefulness: useful/not useful /allows you to self-monitor

- Time & effect: too much /about right/ok

- Burdensome: difficult/complicated/repetitive

- Acceptable: intrusive or inappropriate

- Any particular questions those were hard to understand or answer? Or which were particularly helpful (e.g., for self-monitoring)?

- Repeat these questions in relation to the patient diary.

- Adherence to therapy

- The study therapy is taken three times a week by injection – how are you getting on with that? Have you used the ‘help’ sheets; if so, are they helpful?

- (Participant may still be getting nurses help)

- Difficult/easy/no real problem

- Burdensome

- Any practical issues? - injecting, remembering to do it, feeling well enough.

- Anything which might make it easier/ simpler for you?

- Thank you for taking part in this interview.

- Interview B

- A follow-up interview will be carried out towards the end, or following completion, of the study therapy. Participants who do not complete the study therapy regime will be interviewed shortly after stopping it. The interview will begin with general questions regarding the participant’s current health, how their [non-trial] treatment is going generally and how long they have been taking their study therapy/ how long ago they stopped their study therapy. The following topics will then be explored:

- Patients’ experience of the intervention and its perceived effects – positive and negative

- How have your experiences of the study therapy been?

- Acceptability and feasibility of the mode of study therapy delivery/

- How did the initial dose adjusting period go for you?

- Did the dispensing (dealing with pharmacy) of the study therapy go ok?

- How did the support you received from the study nurse(s) work?

- The study therapy was to be taken three times/ week by injection – how did you get on with that?

- Difficult/easy/no real problem

- Burdensome

- Any practical issues? (e.g., injecting, remembering to do it, feeling well enough)

- Could anything have been done to make it easier/ simpler?

- Acceptability of outcome questionnaires

- We may have asked you this at beginning of trial but can we ask again

- Do the questions ask you about the issues/symptoms/effects that are experiencing or concerning/worrying/ you at this point?

- Are there some issues/symptoms/effects that you feel are missed out by the questions?

- Any questions which seemed irrelevant? How do you feel generally about filling in the questionnaires?

- Prompts:

- Usefulness: useful/not useful /allows you to self-monitor

- Time & effect: too much /about right/ok

- Burdensome: difficult/complicated/repetitive

- Acceptable: intrusive or inappropriate

- Any particular questions those were hard to understand or answer? Or which were particularly helpful (e.g., for self-monitoring)?

- Repeat these questions in relation to the patient diary.

- Any other treatments or interventions used by the patient.

- Have you used any other herbal remedies/complementary therapies or different approaches during the trial period?

- Acceptability of participating in the trial

- What are your feelings generally about being involved in the MAB study?

- Time

- Emotions

- Self-care

- Health - symptoms

- Placebo/ or mistletoe therapy

- Do you think you know whether you were randomised to mistletoe or placebo?

- Why do you think that?

- Thank you for taking part in this interview.

Appendix E. Topic Guide for Qualitative Interviews with Healthcare Professionals

- Professional role

- Please could you tell me your job title and give me a brief description of your professional role (length of time in current and other relevant roles)

- Do you have any training in complementary therapies or anthroposophical medicine?

- About the Mistletoe study

- What are your views about the likely recruitment (any obstacles to this)?

- How acceptable and feasible do you think the mode of delivery for the intervention will be (sub-cutaneous self-injection taught by a research nurse)?

- What is your view on the likely attrition rate?

- What do you think about the proposed placebo?

- What are your views on the potential for success in blinding?

- Views on Mistletoe

- We will be using mistletoe as an adjunct treatment to cancer in the MAB trial.

- What do you know about mistletoe as a treatment?

- We will be using extract of mistletoe, or ‘Viscum album,’ as a herbal medicine for people with breast cancer as it may help to ameliorate the side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy

- What are your views on this in terms of acceptability to healthcare professionals and patients?

- Views on and experience of herbal remedies and complementary therapies

- Have you used herbal remedies or any other complementary therapies?

- How about family and friends?

- Which remedies/therapies? / For what reason? / What or who influenced you/ them to use that? / Did you find it helpful?

- If you have not used CAM remedies/therapies, have you ever considered using them? Why/ not?

- Local availability of complementary therapies

- Are you aware of any complementary therapy resources available in your unit / practice / locally?

- Role of complementary therapies in cancer

- What role, if any, do you feel complementary therapies might play in cancer care?

- Have any of your cancer patients ever requested information or advice about complementary therapies? How do you respond?

- Do patients ever tell you that they are using complementary therapies? How do you respond?

- Do you ever ask cancer patients whether or not they are using any complementary therapies?

- Have you offered advice or information about complementary therapies to a cancer patient or referred anyone for complementary therapy?

- If so, was that because you thought it would be a good idea or because they had asked?

- Complementary therapies and the NHS

- Do you feel complementary therapies should be integrated into the NHS?

- What do you see as the main barriers to integrating complementary therapies into conventional care?

- Are there any organisational / institutional / policy issues that might facilitate or impede such integration?

- Are some complementary therapies, in your view, better candidates for integration than others? Which ones and why?

- Do you think some complementary therapies are harmful? If so, in what way?

- Do you have any other comments?

- Thank you for taking part in this interview.

Appendix F. Treatment Allocation and Participant Opinion

| Patients’ opinion by allocation | What they said |

|

Iscador P Five responses |

Don’t know n=3 Some weeks because I felt strong and I had a redness after injections, I felt I could have the active part but some weeks, I've just had a feeling my body was in good shape before the diagnosis and I was really active with the kids and I barely reaction overall, I thought I could be on placebo. No text provided. I haven't been told which intervention I received. If I had to guess, I would say I received the Active intervention. This is because I feel I coped really well with chemo and hardly experienced any side effects and have been able to carry on with normal day to day activities - including looking after my 2 children. Active n=2 I had a red reaction most of the time after injecting. My family commented how well I looked and coped through chemo. I was able to be active around the house throughout the treatments. Bearing in mind I have been in lockdown since March and had to self-isolate from late January, some of the results have been warp by the isolation. I feel that the results would have been a lot better under normal circumstances but were a lot better than they would have been without mistletoe. Side effects of chemotherapy were mild and manageable for the majority of the 6 cycles of treatment. I felt well and was able to lead a normal life. Covid lockdown in cycle 3 was more of a hindrance and did affect my emotional wellbeing where I was unable to see friends or my partner. I feel that I 'got away' with chemotherapy side effects due to mistletoe injections. |

|

Iscador M 4 responses and 1 not complete T2 questionnaire. |

Don’t know n=1 Just do not know. I had a large reaction once and my partner said' you must be on the active intervention' but I felt that I could have had the reaction with… (incomplete) Active n=2 I felt I was having the active intervention. I did notice the difference in Cycles 2 and 3 of chemo, my energy levels had increased. Also, as the dose gradually increased to 10mg I encountered extreme reactions almost like hives. The area was raised, hot to touch and was large in diameter. I then went back to a reduced dose of 1mg for the rest of the trial. I have suffered with considerable fatigue during and post chemo and radiotherapy. I do not know if this was made better by receiving mistletoe injections hence my response to question 11 above. I would be very interested to learn whether I had the agent or a placebo, if it transpires it was the guess then I guess without it the fatigue would have been even worse. Placebo n=1 I may have been on the placebo as I had most of the symptoms given in the booklet, I read except that I did not get feeling sick. |

|

Placebo 3 responses and 1 did complete T2 questionnaire. |

Don’t know n=1 I don't know what I have been taking - active or placebo. Placebo n=2 I've not had any reaction to the injection which suggests placebo, but I have also been very lucky with mild symptoms to my treatment which suggests active. No skin reaction to injections |

Appendix G. Adverse Events

| Participant | Description | CTCAE | Seriousness | Intensity | Expected | Causality |

| A | Pain on injection site | 1 | Not serious | Mild | 1 | Definite |

| Skin reaction of ≥5cm | 1 | Not serious | Mild | 1 | Definite | |

| B | Bruising | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Not related |

| C | Pain at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Mild | 1 | Not related |

| Skin in duration @injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite | |

| D | Pain at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

| Bruise at injection site | *5 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Not related | |

| Red patch 1cm, itchy & small lump | 1 | Scored as 5 | not reported | 1 | Definite | |

| Redness & itching at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite | |

| E | Haematoma | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

| Pain on injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | Not reported | Definite | |

| Skin rash at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite | |

| Cutaneous rash, skin reaction | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite | |

| Cutaneous rash bilateral thigh | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

- Adverse events from participants on Iscador M n=4/5 participants

| Participant | Description | CTCAE | Seriousness | Intensity | Expected (1) Not expected (2) |

Causality |

| F | Skin reaction | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Probable |

| Lumps in stomach | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Possible | |

| G | Skin reaction at injection site ≥5cm | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

| H | Bruise at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

| I | Pain on injection site | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

| Local skin reaction | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

- Adverse events from participants on placebo (n=2/4 participants)

| Participant | Description | CTCAE | Seriousness | Intensity | Expected | Causality |

| J | Discomfort at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Mild | 1 | Definite |

| Pain at injection site | 1 | Not serious | Mild | 1 | Definite | |

| K | Bruise at site of injection | 1 | Not serious | Not reported | 1 | Definite |

Appendix H. CAMBI Questionnaire at T0 (baseline)

References

- Mistletoe therapy: Information for doctors Accessed at Mistletoe therapy: Information for doctors (mistletoe-therapy.org) on 01.06.25.

- Schnell-Inderst P, Steigenberger C, Mertz M, Otto I, Flatscher-Thöni M, Siebert U. Additional treatment with mistletoe extracts for patients with breast cancer compared to conventional cancer therapy alone - efficacy and safety, costs and cost-effectiveness, patients and social aspects, and ethical assessment. Ger Med Sci 2022 Jul 14;20: Doc10. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mistletoe centres in the UK Accessed at Centres – Mistletoe Therapy UK on 01.06.25.

- NHS Long Term Plan ambitions for cancer accessed at NHS England » NHS Long Term Plan ambitions for cancer on 01.06.23.

- Bryant S, Duncan L, Feder G, Huntley AL. A pilot study of the mistletoe and breast cancer (MAB) trial: a protocol for a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2022 Apr 6;8(1):78. [CrossRef]

- The ECOG Performance Status Scale accessed at ECOG Performance Status Scale - ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group on 01.06.25.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JCJM et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85(5):365-76. [CrossRef]

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, te Velde A, Muller M, Franzini L, Williams A, de Haes HC, Hopwood P, Cull A, Aaronson NK. European Organization for Research & Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a 3-country field study. J Clin Oncol 1996 Oct; 14(10):2756-68. [CrossRef]

- Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Ding B, Malin J, Peterman A, Calhoun E, Cella D. Measuring health-related quality of life and neutropenia-specific concerns among older adults undergoing chemotherapy: validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Neutropenia (FACT-N). Support Care Cancer 2008 16(1):47-56. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: a brief, three-dimensional, self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 19 (1): 5-14, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Kröz M, Feder G, von Laue H, Zerm R, Reif M, Girke M, Matthes H, Gutenbrunner C, Heckmann C. Validation of a questionnaire measuring the regulation of autonomic function. BMC Complement Altern Med 2008; 8:26. [CrossRef]

- Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith G. Developing a measure of treatment beliefs: the complementary and alternative beliefs inventory. Comp Ther Med 2005; 13(2): 144-9. [CrossRef]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0, November 27, 2017, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

- Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Well-being 2014;9(1):26152. [CrossRef]

- Tracy SJ. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry 2010;16(10):837-51. [CrossRef]

- UK breast cancer statistics in men accessed https://www.wcrf-uk.org/preventing-cancer/uk-cancer-statistics/ on 01.06.25.

- Horneber M, van Ackeren G, Linde K, Rostock M. Mistletoe therapy in oncology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003297. [CrossRef]

- Wider B, Rostock M, Huntley A, van Ackeren G, Horneber M. Mistletoe extracts for cancer treatment (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD014782. [CrossRef]

- Loef M, Walach H. Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020 Jul 20;20(1):227. [CrossRef]

- Freuding M, Keinki C, Kutschan S, Micke O, Buentzel J, Huebner J. Mistletoe in oncological treatment: a systematic review: Part 2: quality of life and toxicity of cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019 Apr;145(4):927-939. Epub 2019 Jan 2. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Wright F, Duncan LJ, Huntley AL. Profiling MT research and identifying evidence gaps: A systematic review of conditions treated, mode of application and outcomes. Eur J Integrat Med 2022 49: 101392. [CrossRef]

- Tröger W, Zdrale Z, Tišma N, Matijašević M. Additional Therapy with a Mistletoe Product during Adjuvant Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer Patients Improves Quality of Life: An Open Randomized Clinical Pilot Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014:2014:430518. [CrossRef]

- Semiglasov VF, Stepula VV, Dudov A, Lehmacher W, Mengs U. The Standardised Mistletoe Extract PS76A2 Improves QoL in Patients with Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant CMF Chemotherapy: A Randomised, Placebo-controlled,Double-blind, Multicentre Clinical Trial. Anticancer research 2004 24: 1293-1302.

- Semiglasov VF, Stepula VV, Dudov A, Lehmacher W, Mengs U. Quality of Life is Improved in Breast Cancer Patients by Standardised Mistletoe Extract PS76A2 during Chemotherapy and Follow-up: A Randomised, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind, Multicentre Clinical Trial. Anticancer Research 2006 26: 1519-1530.

- Evans M, Bryant S, Huntley AL, Feder G. Cancer Patients' Experiences of Using Mistletoe (Viscum album): A Qualitative Systematic Review and Synthesis. J Altern Complement Med 2016 22(2):134-44. [CrossRef]

| Participant characteristics |

Cancer characteristics |

|||||||||

|

Mean age (yrs) |

Age range (yrs) |

Identified as | Education | Occupation | Laterality | Stage | Tumour size | Nodes | ER status | |

| 49 | 36-76 | White British n=11 White other background n=3 Chinese n=1 |

No formal qualifications n=1 Secondary n=2 Further n=2 Higher n=9 |

Employed n=11 retired n=1 unemployed due to ill health n=1 |

Right =7 Left =7 |

Stage one = 3 Stage two =9 Stage three =2 |

T1= 2 T2=12 |

N0=7 N1=4 N2=2 N3=1 |

ER+= 10 ER-=4 |

| Feasibility outcomes | Illustrative quotes |

| A Recruitment | |

| Awareness of mistletoe therapy |

A1 “Never heard of it before” Participant G. A2 “The berries are poisonous, so this was quite interesting. I was like ‘mistletoe?’ (laughs) Gosh, ok” Participant K. A3 “A while back it was quite a popular thing for people to try … for their metastatic cancer. A lot of patients were looking at getting that in the private sector” Oncologist A. |

| Barriers to recruitment |

A4 “If it will help me then I’ll have it, but I find it hard to inject myself.” Participant G. A5 “Initially I said no ‘cos of all the extra hospital appointments … with the little one and we live out at (village X) so getting to the hospital (is difficult)” Participant B. |

| Enablers to recruitment |

A6 “I thought it was a chance to maintain my family life by reducing my side effects” Participant H. A7 “Having a natural product that could alleviate something like a chemo treatment, I found the idea of that absolutely amazing” Participant J. A8 “I said ‘yes I’d like to go ahead with it’ because I did see that Germany, Switzerland and Holland had already started using it and I did a bit of research and people were paying for it privately in America and this country …. I just thought anything that will give me an edge as well is absolutely going to help. Help me and also other people for the future, so it’s win-win” Participant J. A9 “If I am finding this too much, I can say no… the other things I didn’t have control over” Participant C. A10 “[Patients] question if there is any trial they would be eligible for, having mistletoe, because I think they in a way are aware …. The thing is patients are interested; I find them to be more interested” Research Nurse A. A11 “[Patients were] clearly enthusiastic about potentially entering the study …. Happy to do any extra attendances that might be necessary” Oncologist A. |

| B Retention & adherence | |

| Barriers to retention and adherence |

B1 “When you don’t like needles then you’ll always be terrified by needles” Participant H. B2 “You have to build the injection up yourself … in some ways I found that quite difficult because you’ve got time to think about what you’re doing and I’d rather not, I’d rather just take something out of a packet and off. Yeah. So in a way it prolonged the agony” Participant J. B3 “I kind of feel like if someone notices that she’s not reacting then she probably will think she’s on placebo and may drop off. So far it didn’t happen but I can’t really say it’s not going to” Research Nurse A. B4 “It’s proven to be a bit tiresome, I must be honest with you, having to come into oncology … we have to keep going back weekly and it means coming into the city and it’s a nightmare to park and all of those things” Participant D. B5 “Well I have to say I didn’t like going [to the hospital]… it did make it more stressful because obviously the place you don’t want to go to is the place you’ve got to go to, but they temperature checked you at the door on the way in, I had a mask, I had gloves, they had masks and you just had to get on with it really” Participant F. B6 “I had the first week of radio and then .... I kept forgetting to take it” Participant A. B7 ““Once I’d finished the other treatment then the mistletoe became kind of secondary …. After my last radiotherapy I rang the bell and my husband and my daughter were there with me and that was a real kind of emotional moment and it felt like a real sense of closure and yet with the mistletoe, that was still going on, so it wasn’t a closure” Participant E. |

| Enablers to retention and adherence |

B8 “It was painful and it was irritating me, I was like ‘oh I can’t be doing with this’ and I did have thoughts ‘oh shall I just finish with it?’ And then in the back of my mind I just thought ‘well would I really be having these reactions if I was on placebo? I just kind of had to ride the storm basically and I’m glad I did because I ended up sort of talking to myself going right, ok, there are positives to this, this is uncomfortable at the moment but, you know, it’s not going to last’” Participant C. B9 “I had a blog page …. I told them all about the mistletoe on that and I got a very positive response” Participant D. B10 “Even if they’d said they got a skin reaction and we’d said ‘ok, tell us about that, is that problematic’, they were still really keen to kind of carry on and say ‘no, I really want to do this and it’s fine’ …. So once they’d signed up to it they really wanted to persevere and see it through” Research Nurse C. B11 “I’ve got an alarm on my phone that goes off in the morning, I’ve chosen Justin Bieber’s classic hit ‘Mistletoe’ to remind me!” Participant E. B12 “What we were concerned about is the injecting themselves. So they seem to be coping alright …[and] they all seem to be sort of happy to be carrying on with it which is actually more surprising” Research Nurse B. B13 “To begin with I was a bit uncertain, but when I saw they were accepting it quite easily I thought that was quite good and they didn’t have any side effects. And none of them complained to me about being tired, whereas 99% of the people, if you look at any of my letters …. would have toxicity and fatigue” Oncologist B. |

| C Assessment of blinding |

C1 “What makes me think I might have had the placebo because I’ve had no skin reactions at all” Participant F. C2 “I viewed [the skin reaction] as possibly having the actual mistletoe injection instead of a placebo so I was like this is good, I’ve actually got the mistletoe (laughs) so I was quite pleased.... I think with the reaction that I had and the way that I felt throughout chemotherapy, I would lean more towards thinking that I had had either mistletoes, but like I say you never know, maybe it was all in my mind. But I think, yeah, I think that I did have mistletoe.” Participant B. C3 “I feel very strongly that it was the mistletoe …. I was ready for the [chemotherapy] side effects and I didn’t have them … All I had was hunger” Participant K. C4 “I don’t know if it was the mistletoe that sort of helped or if it was just the frame of mind, I honestly couldn’t tell you” Participant A. C5 “Some people were saying I don’t think I had it because I still had some side effects or there were others that said I think I did have it because I felt great all the way through, but I think they definitely had an opinion as to whether they were on it” Research Nurse C. C6 “So the colour of the [mistletoe] liquid is probably a light yellow but the saline is … colourless.… I can say from week four I can see the difference” Research Nurse A. |

| D Adverse events | Relevant quotes in B and C e.g., B8, B9 & C2 |

| E Questionnaire data |

E1 "There was some slightly odder questions than others. There was a couple of questions about my sex life which I thought was interesting, a bit left-field." Participant E. E2 "... there were questions about kind of, you know, like your sex life and that sort of… Some of that obviously, yeah, ... I just put not applicable" Participant C. |

| F Complementary and alternative medicine beliefs |

F1 “I fully understand the power of plants ... But I don’t fully believe they can cure everything ‘cos I think there is a place for engineered drugs if you need them. I think it’s a complementary thing” Participant F. F2 “To be perfectly honest I don’t really think about it … just go with the flow” Participant A, who had not used CAM therapies previously. F3 “I think mainstream treatment should absolutely sit alongside kind of complementary or additional therapies because if it’s improving their general health, wellbeing, emotional and physical kind of health then that’s great” Research Nurse C. F4 “I tend to be fairly relaxed about patients taking …. complementary medicines because I think at the very least you’ll be harnessing a placebo and potential psychological benefits, and then there may be added benefits. Now if it’s got a very active ingredient or there’s something unknown about it then I’d be more cautious ‘cos I think we just don’t have any evidence about the interactions” Oncologist A. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).