Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Problem Statement and Context

Gap Analysis

Objectives and Review Questions

Methods

Protocol Registration

Eligibility Criteria

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction

Quality Assessment

Data Synthesis and Statistical Methodology

Results

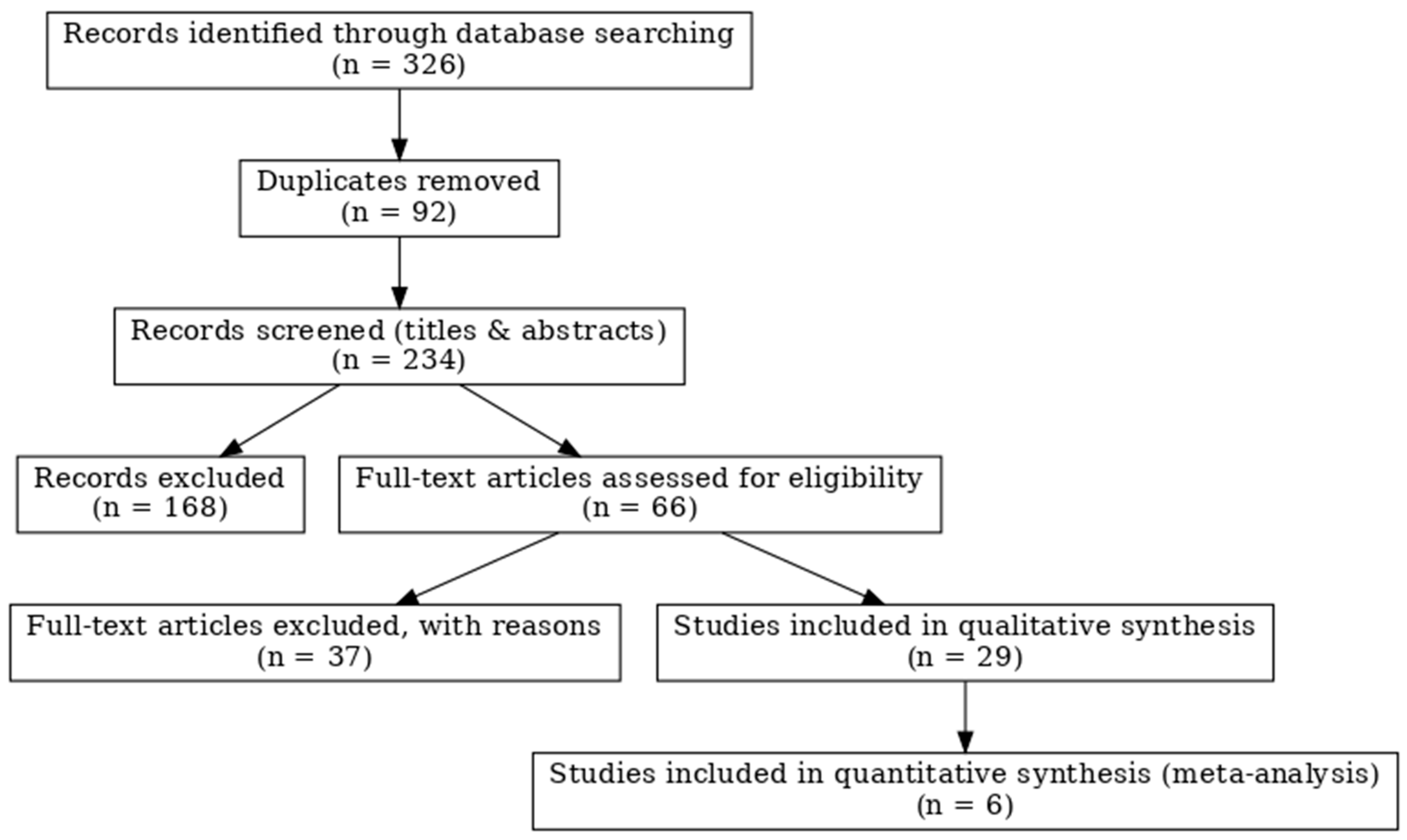

Study Selection

Study Characteristics

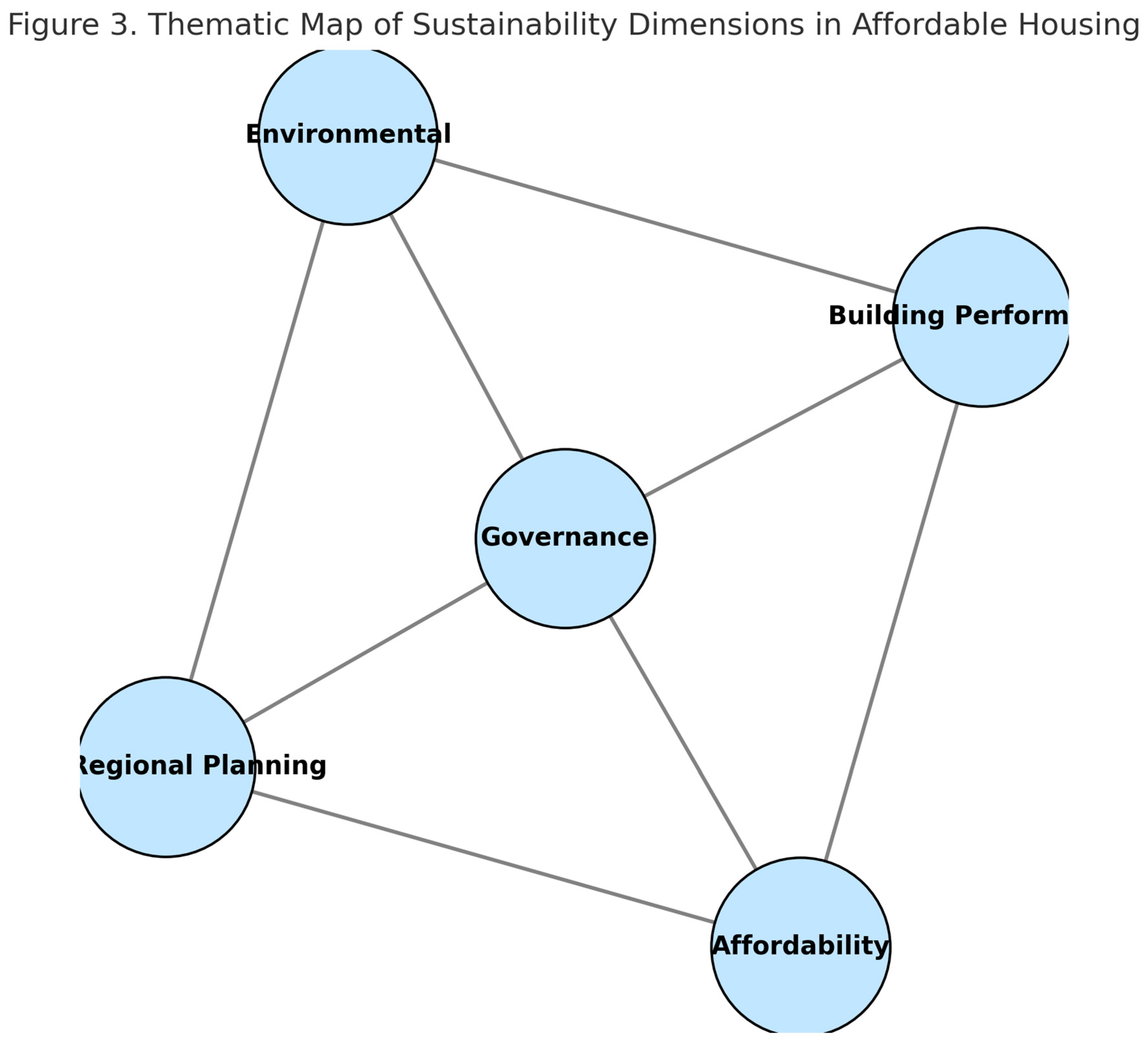

Synthesis of Findings

Agreements and Disagreements

| Theme | Consensus Findings | Contradictions / Debates | Representative Studies |

| Energy Efficiency | Most studies agree efficiency upgrades reduce operational energy demand. | Debate over embodied energy trade-offs. | Mete & Xue (2021); Francart et al. (2022) |

| Material Circularity | Strong support for recycling and reuse as sustainability levers. | Concerns about scalability and costs. | Yeganeh et al. (2021); Fensterseifer et al. (2022) |

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

Comparison with Existing Literature

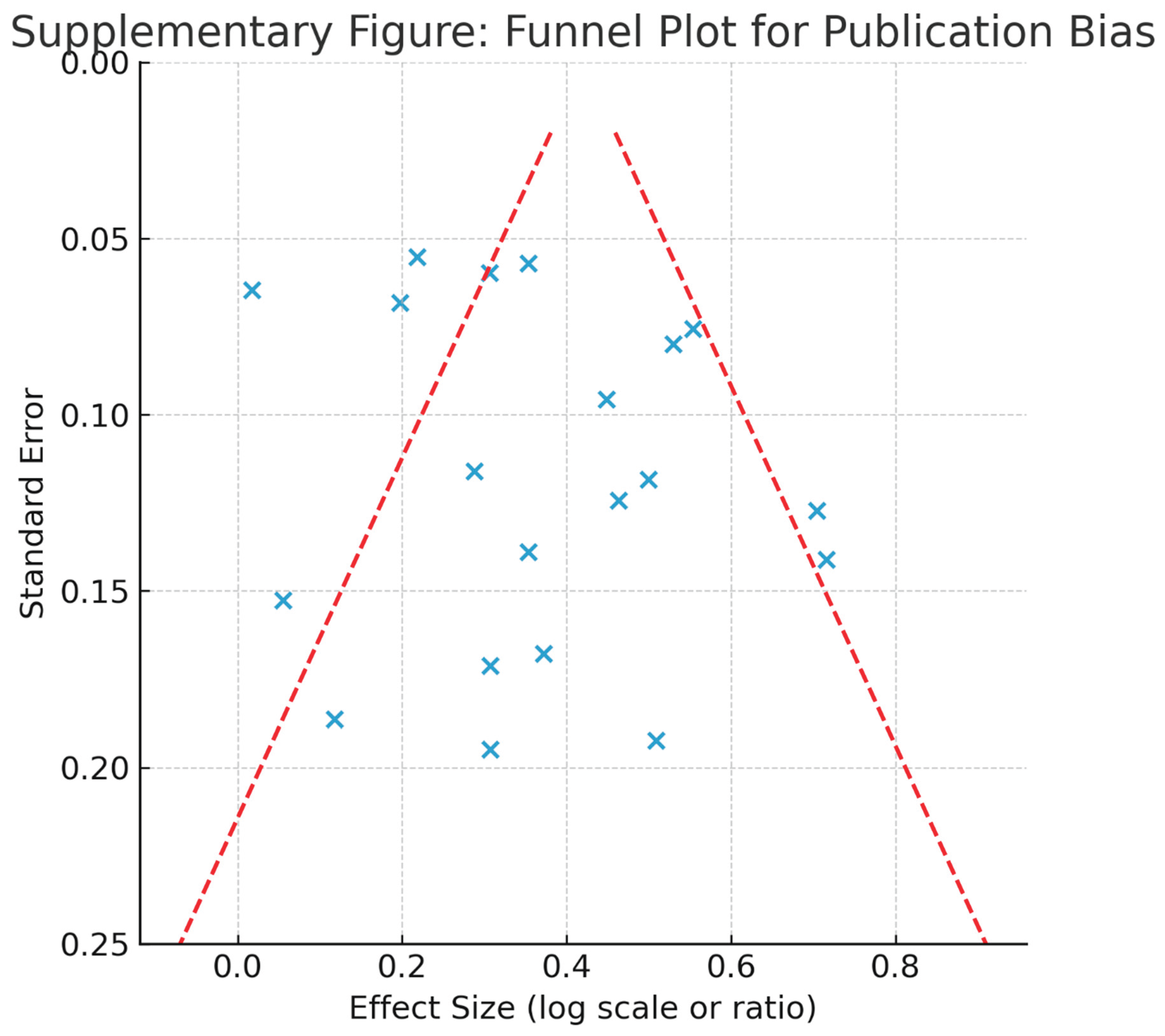

Strengths and LimitationsStrengths of the Evidence Base

Limitations of the Evidence Base

Strengths and Limitations of This Review

Implications

Practice

Policy

Research

Unanswered Questions and Gaps

| Gap / Limitation | Why it matters | Suggested Future Research Direction |

| Limited integration of social equity in sustainability metrics | Affordability and inclusiveness are often overlooked, undermining real-world impact. | Develop holistic frameworks incorporating equity, affordability, and cultural relevance. |

| Scarcity of longitudinal studies on building performance | Most evidence comes from short-term projects, limiting understanding of long-term sustainability outcomes. | Encourage funding and design of longitudinal housing studies across diverse contexts. |

| Underrepresentation of Global South case studies | Current evidence is dominated by studies from Europe and North America, reducing global applicability. | Expand research in low- and middle-income regions to capture diverse sustainability challenges. |

| Fragmented governance analysis | Governance is acknowledged but rarely empirically analyzed, limiting knowledge on policy mechanisms. | Conduct comparative governance studies across jurisdictions to identify enabling conditions. |

Controversies and Ongoing Debates

Conclusions

Key Messages

Recommendations

For Practitioners

For Policymakers

For Researchers

Future Research Directions

References

- World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities; Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Founoun, A.; Hayar, A. In Evaluation of the concept of the smart city through local regulation and the importance of local initiative.In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Kansas City, MO, USA, 16–19 September 2018; pp. 1–6.

- Ali, C. H.; Roy, D.; Amireche, L; An application case study in Algiers: Antoni, J.-P. Development of a Cellular Automata-based model approach for sustainable planning of affordable housing projects.

- Cubillos-González, R.-A.; Cardoso, G.T. Cubillos-González, R.-A.; Cardoso, G.T. Affordable housing and clean technology transfer in construction firms in Brazil. Technol. Soc. 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Koetter, T.; Sikder, S.K.; Weiss, D. Koetter, T.; Sikder, S.K.; Weiss, D. The cooperative urban land development model in Germany-An effective instrument to support affordable housing. Land Use Policy, 1054. [Google Scholar]

- Mete, S.; Xue, J. Mete, S.; Xue, J. Integrating environmental sustainability and social justice in housing development: Two contrasting scenarios. Prog. Plan. 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yozbakee, H.A.A.K.; Sanjary, H.A.R.H.A. Al-Yozbakee, H.A.A.K.; Sanjary, H.A.R.H.A. Evaluating the functional performance of the entrance space in apartments of local affordable multi-family housing. Mater. Today Proc. 1083. [Google Scholar]

- Boobalan, S.; Sailesh, S.; Sammuvel, M.R. Boobalan, S.; Sailesh, S.; Sammuvel, M.R. Study on innovative residential buildings concept for economically weaker sections. Mater. Today Proc.

- Cavicchia, R; Entangled housing and land use policy limitations and insights from Oslo: Housing accessibility in densifying cities.

- Francart, N.; Polycarpou, K.; Malmqvist, T.; Moncaster, A. Francart, N.; Polycarpou, K.; Malmqvist, T.; Moncaster, A. Demands, default options and definitions: How artefacts mediate sustainability in public housing projects in Sweden and Cyprus. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 1027. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, X.; Lin, M. Ge, J.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, X.; Lin, M. Study on the suitability of green building technology for affordable housing: A case study on Zhejiang Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 1226. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.P.; Adabre, M.A. Chan, A.P.; Adabre, M.A. Bridging the gap between sustainable housing and affordable housing: The required critical success criteria (CSC). Build. Environ.

- Beizaee, A.; Morey, J.; Badiei, A. Beizaee, A.; Morey, J.; Badiei, A. Wintertime indoor temperatures in social housing dwellings in England and the impact of dwelling characteristics. Energy Build. 1108. [Google Scholar]

- Fensterseifer, P.; Gabriel, E.; Tassi, R.; Piccilli, D.G.A.; Minetto, B. Fensterseifer, P.; Gabriel, E.; Tassi, R.; Piccilli, D.G.A.; Minetto, B. A year-assessment of the suitability of a green façade to improve thermal performance of an affordable housing. Ecol. Eng. 1068. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, S.; Paolini, R.; Synnefa, A.; De Torres, L.; Prasad, D.; Santamouris, M. Haddad, S.; Paolini, R.; Synnefa, A.; De Torres, L.; Prasad, D.; Santamouris, M. Integrated assessment of the extreme climatic conditions, thermal performance, vulnerability, and well-being in low-income housing in the subtropical climate of Australia. Energy Build. 1123. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, J.; Bardhan, R. Malik, J.; Bardhan, R. Energy target pinch analysis for optimising thermal comfort in low-income dwellings. J. Build. Eng. 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, J.; Bardhan, R. Malik, J.; Bardhan, R. A localized adaptive comfort model for free-running low-income housing in Mumbai, India. Energy Build. 1127. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, J.; Carrere, J.; Salom, J.; Novoa, A.M. Ortiz, J.; Carrere, J.; Salom, J.; Novoa, A.M. Energy consumption and indoor environmental quality evaluation of a cooperative housing nZEB in Mediterranean climate. Build. Environ. 1097. [Google Scholar]

- Arun, M.; Baskar, K.; Geethapriya, B.; Jayabarathi, M.; Angayarkkani, R. Arun, M.; Baskar, K.; Geethapriya, B.; Jayabarathi, M.; Angayarkkani, R. Affordable housing: Cost effective construction materials for economically weaker section. Mater. Today Proc. 7838. [Google Scholar]

- Kjærås, K.; Haarstad, H. Kjærås, K.; Haarstad, H. A geography of repoliticisation: Popularising alternative housing models in Oslo. Political Geogr. 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, D.J.; Dash, S.P. Pati, D.J.; Dash, S.P. Strategy for promoting utilization of non-biodegradable wastes in affordable housing in India. Mater. Today Proc.

- Patil, D.; Bukhari, S.A.; Minde, P.R.; Kulkarni, M.S. Patil, D.; Bukhari, S.A.; Minde, P.R.; Kulkarni, M.S. Review on comparative study of diverse wall materials for affordable housing. Mater. Today Proc.

- Pawar, P.; Minde, P.; Kulkarni, M. Pawar, P.; Minde, P.; Kulkarni, M. Analysis of challenges and opportunities of prefabricated sandwich panel system: A solution for affordable housing in India. Mater. Today Proc. 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, R.; Bhattacharya, S.P.; Chattopadhyay, S. Sen, R.; Bhattacharya, S.P.; Chattopadhyay, S. Are low-income mass housing envelops energy efficient and comfortable? A multi-objective evaluation in warm-humid climate. Energy Build. 1110. [Google Scholar]

- Unni, A.; Anjali, G. Unni, A.; Anjali, G. Cost-benefit analysis of conventional and modern building materials for sustainable development of social housing. Mater. Today Proc. 1649. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjian, M. Gorjian, M., Luhan, G. A., & Caffey, S. M. (2025). Analysis of design algorithms and fabrication of a graph-based double-curvature structure with planar hexagonal panels. [CrossRef]

- Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences; //easychair: , 11(2), 1–29. https.

- A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations; //oaktrust: (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. https.

- Gorjian, M; A comprehensive survey: , Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2025). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods. [CrossRef]

- Raina, A. S., Mone, V., Gorjian, M., Quek, F., Sueda, S., & Krishnamurthy, V. R. (2024). Blended physical-digital kinesthetic feedback for mixed reality-based conceptual design-in-context. In Proceedings of the 50th Graphics Interface Conference (Article 6; pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations; //oaktrust: (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. https.

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review (2020–2024) [Preprint]: (2025). Advances and challenges in GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; Empirical findings from Denver: (2025). Analyzing the relationship between urban greening and gentrification. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A critical review of statistical methodologies: (2025). From deductive models to data-driven urban analytics. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review of advances: (2025). GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A scoping review of urban greening’s social impacts [Preprint: (2025). Green gentrification and community health in urban landscape. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review of economic and social impacts using spatial-statistical methods [Preprint]: (2025). Green schoolyard investments and urban equity. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Gorjian, M. (2025). Green schoolyard investments influence local-level economic and equity outcomes through spatial-statistical modeling and geospatial analysis in urban contexts. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Gorjian, M. (2025). Greening schoolyards and the spatial distribution of property values in Denver, Colorado. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review of geospatial and statistical evidence [Preprint]: (2025). Greening schoolyards and urban property values. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic international review of model performance and interpretability [Preprint]: (2025). Integrating machine learning and hedonic regression for housing price prediction. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A critical review [Preprint]: (2025). Methodological advances and gaps in urban green space and schoolyard greening research. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A critical review of definitions: (2025). Quantifying gentrification. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Gorjian, M. (2025). Schoolyard greening, child health, and neighborhood change. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; Quantitative models: (2025). Spatial economics. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A comprehensive review of quantitative approaches to sustainable urban form [Preprint]: (2025). Statistical methodologies for urban morphology indicators. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review of GIS-based methodologies and applications [Preprint]: (2025). Statistical perspectives on urban inequality. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Gorjian, M. (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on residential property values. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review[Preprint: (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on surrounding residential property values. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M; A systematic review of child health and neighborhood change [Preprint]: (2025). Urban schoolyard greening. [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.V.; Teja, P.S.; Siddhartha, K.S.; Rama, J.K. Raj, P.V.; Teja, P.S.; Siddhartha, K.S.; Rama, J.K. Housing with low-cost materials and techniques for a sustainable construction in India-A review. Mater. Today Proc. 1850. [Google Scholar]

- Wesonga, R.; Kasedde, H.; Kibwami, N.; Manga, M. Wesonga, R.; Kasedde, H.; Kibwami, N.; Manga, M. A comparative analysis of thermal performance, annual energy use, and life cycle costs of low-cost houses made with mud bricks and earthbag wall systems in Sub-saharan Africa. Energy Built Environ.

- Dabush, I.; Cohen, C.; Pearlmutter, D.; Schwartz, M.; Halfon, E. Dabush, I.; Cohen, C.; Pearlmutter, D.; Schwartz, M.; Halfon, E. Economic and social utility of installing photovoltaic systems on affordable-housing rooftops: A model based on the game-theory approach. Build. Environ. 1098. [Google Scholar]

- Thadani, H. L; Case study in developing countries: Go, Y.I. Integration of solar energy into low-cost housing for sustainable development.

- Yeganeh, A.; Agee, P.R.; Gao, X.; McCoy, A.P. Yeganeh, A.; Agee, P.R.; Gao, X.; McCoy, A.P. Feasibility of zero-energy affordable housing. Energy Build. 1109. [Google Scholar]

- zu Ermgassen, S.O.; Drewniok, M.P.; Bull, J.W.; Walker, C.M.C.; Mancini, M.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Serrenho, A.C. zu Ermgassen, S.O.; Drewniok, M.P.; Bull, J.W.; Walker, C.M.C.; Mancini, M.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Serrenho, A.C. A home for all within planetary boundaries: Pathways for meeting England’s housing needs without transgressing national climate and biodiversity goals. Ecol. Econ. 1075. [Google Scholar]

- Taruttis, L.; Weber, C. Taruttis, L.; Weber, C. Estimating the impact of energy efficiency on housing prices in Germany: Does regional disparity matter? Energy Econ. 1057. [Google Scholar]

- Abass, A. S; The urban regeneration approach: Kucukmehmetoglu, M. Transforming slums in Ghana.

- Adabre, M.A.; Chan, A.P.; Darko, A. Adabre, M.A.; Chan, A.P.; Darko, A. Interactive effects of institutional, economic, social and environmental barriers on sustainable housing in a developing country. Build. Environ. 1084. [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Gyamfi, A. ; Owusu-Addo, E.; Inkoom, D.K.B; An alternative residential location of low-income migrants in Kumasi: Asibey, M.O. Peri-urban interface.

- Akinwande, T.; Hui, E.C. Akinwande, T.; Hui, E.C. Housing supply value chain in relation to housing the urban poor. Habitat Int. 1026. [Google Scholar]

- Alhajri, M.F. Alhajri, M.F. Housing challenges and programs to enhance access to affordable housing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, S. Alves, S. Divergence in planning for affordable housing: A comparative analysis of England and Portugal. Prog. Plan. 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Asumadu, G.; Quaigrain, R.; Owusu-Manu, D.; Edwards, D.; Oduro-Ofori, E.; Dapaah, S. Asumadu, G.; Quaigrain, R.; Owusu-Manu, D.; Edwards, D.; Oduro-Ofori, E.; Dapaah, S. Analysis of urban slum infrastructure projects financing in Ghana: A closer look at traditional and innovative financing mechanisms. World Dev. Perspect. 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Atia, M; Moroccan slum dwellers’ nonmovements and the art of presence: Refusing a “City without Slums”.

- Boateng, G.O.; Adams, E.A. Boateng, G.O.; Adams, E.A. A multilevel, multidimensional scale for measuring housing insecurity in slums and informal settlements. Cities, 1040. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, C.W.; Lee, C.K. Cheah, C.W.; Lee, C.K. Housing the urban poor through strategic networks: A cross-case analysis. Habitat Int. 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli, F.; Coppola, A.; Belotti, E.; Berruti, G.; Marinaro, I.C.; Curci, F.; Zanfi, F. Chiodelli, F.; Coppola, A.; Belotti, E.; Berruti, G.; Marinaro, I.C.; Curci, F.; Zanfi, F. The production of informal space: A critical atlas of housing informalities in Italy between public institutions and political strategies. Prog. Plan. 1004. [Google Scholar]

- Fatti, C.C. Fatti, C.C. Towards just sustainability through government-led housing: Conceptual and practical considerations. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 1011. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzler, P.A. Dantzler, P.A. Household characteristics or neighborhood conditions? Exploring the determinants of housing spells among US public housing residents. Cities, 1033. [Google Scholar]

- Debrunner, G.; Hartmann, T. Debrunner, G.; Hartmann, T. Strategic use of land policy instruments for affordable housing–Coping with social challenges under scarce land conditions in Swiss cities. Land Use Policy, 1049. [Google Scholar]

- Diller, C.; Velte, N. Diller, C.; Velte, N. A comparative evaluation of housing supply concepts in two larger medium-sized cities in a similar cases design. Eval. Program Plan. 1022. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, R. J.; Moore, T; Understanding the challenges and policy implications: Watkins, C. The use of public land for house building in England.

- Eikelenboom, M.; Long, T.B.; de Jong, G. Eikelenboom, M.; Long, T.B.; de Jong, G. Circular strategies for social housing associations: Lessons from a Dutch case. J. Clean. Prod. 1260. [Google Scholar]

- Ezennia, I.S. Ezennia, I.S. Insights of housing providers’ on the critical barriers to sustainable affordable housing uptake in Nigeria. World Dev. Sustain. 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti, B. ; Saghapour, T.; Turrell, G.; Gunn, L.; Both, A.; Lowe, M.; Rozek, J.; Roberts, R.; Hooper, P; Does city size matter? Health Place 2022: Butt, A. Spatial and socioeconomic inequities in liveability in Australia’s 21 largest cities.

- Górczyn ́ska-Angiulli,M.Theeffectsofhousingproviders’diversityandtenureconversiononsocialmix. Cities, 1043.

- Goytia, C.; Heikkila, E.J.; Pasquini, R.A. Goytia, C.; Heikkila, E.J.; Pasquini, R.A. Do land use regulations help give rise to informal settlements? Evidence from Buenos Aires. Land Use Policy, 1064. [Google Scholar]

- Hassen, F. S.; Kalla, M; A case study of Hassi Bahbah city in Algeria: Dridi, H. Using agent-based model and Game Theory to monitor and curb informal houses.

- Hueppe, R.V. Hueppe, R.V. “The land will stay”: Lessons for inclusive, self-organizing housing projects. City Cult. Soc. 1004. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, A. ; Meijer, R; Quantitative targets and qualitative ambitions in Dutch housing development: Hartmann, T. Land for housing.

- Kalantidou, E; The need for and feasibility of sustainable housing in Australia: Housing precariousness.

- Keep, M. ; Montanari, B; Reactions to slum resettlement as social inclusion in Tamesna: Greenlee, A.J. Contesting “inclusive” development.

- Leon-Moreta, A.; Totaro, V. Leon-Moreta, A.; Totaro, V. US cities’ permitting or restriction of housing development. Cities, 1038. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C. ; Hui, E.C.; Yip, T.L; The Influence of a Government Announcement on Housing Markets in Hong Kong: Huang, Y. Private land use for public housing projects.

- Liu, Z; A before-after relocation assessment: ; Ma, L. Residential experiences and satisfaction of public housing renters in Beijing, China.

- Mahdi, Z; A wicked problem perspective: ; Mazumder, T.N. Re-examining the informal housing problem in Delhi.

- Margier, A; Innovative solution to address homelessness or preclusion of radical housing practices? Cities 2023: The institutionalization of ‘tiny home’villages in Portland.

- Mohorcˇich, J. Mohorcˇich, J. Is opposing new housing construction egalitarian? Rent as power. Cities, 1042. [Google Scholar]

- Ogas-Mendez, A. F; The role of the informal housing market: Isoda, Y. Obstacles to urban redevelopment in squatter settlements.

- Sharafeddin, A.; Arocho, I. Sharafeddin, A.; Arocho, I. Toward sustainable public housing: A comparison of social aspects in public housing in the United State and Libya. Habitat Int. 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbyna, A. Shcherbyna, A. Towards a concept of sustainable housing provision in Ukraine. Land Use Policy, 1063. [Google Scholar]

- Soma, H.; Sukhwani, V.; Shaw, R. Soma, H.; Sukhwani, V.; Shaw, R. An approach to determining the linkage between livelihood assets and the housing conditions in urban slums of Dhaka. J. Urban Manag.

- Squires, G.; Hutchison, N. Squires, G.; Hutchison, N. Barriers to affordable housing on brownfield sites. Land Use Policy, 1052. [Google Scholar]

- Tjia, D.; Coetzee, S. Tjia, D.; Coetzee, S. Geospatial information needs for informal settlement upgrading–A review. Habitat Int. 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Vaid, U; Assessing housing quality impacts of slum redevelopment in India: Delivering the promise of ‘better homes’?

- Wang, W. ; Wu, Y; The impact of public housing supply on urban inclusive growth in China: Choguill, C. Prosperity and inclusion.

- Wijburg, G. Wijburg, G. The governance of affordable housing in post-crisis Amsterdam and Miami. Geoforum.

- Woo, A. ; Joh, K; Individual perception of public housing and housing price depreciation: Yu, C.-Y. Who believes and why they believe.

- Wu, Y. ; Luo, J; Theory and practice of housing vouchers: Peng, Y. An optimization-based framework for housing subsidy policy in China.

- Zhou, K.; Zimmermann, N.; Warwick, E.; Pineo, H.; Ucci, M.; Davies, M. Zhou, K.; Zimmermann, N.; Warwick, E.; Pineo, H.; Ucci, M.; Davies, M. Dynamics of short-term and long-term decision-making in English housing associations: A study of using systems thinking to inform policy design. EURO J. Decis. Process. 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y; Tug-of-war between marketization and state intervention: Paradigm shifts in China’s housing policy.

- Gao, Y.; Tian, L.; Ling, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y. Gao, Y.; Tian, L.; Ling, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y. From welfarism to entrepreneurialism: Impacts of the “shanty-area renovation” scheme on housing prices in China. Habitat Int. 1028. [Google Scholar]

- Menzori, I. D.; de Sousa, I.C.N; Spatial repercussions on urban growth: Gonçalves, L.M. Local government shift and national housing program.

- Pan, W; A critical review of strategies and policies of urban village renewal in Shenzhen: ; Du, J. Towards sustainable urban transition.

- Woo, A. ; Yu, C.-Y; Revisiting neighborhood environments of Housing Choice Voucher and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit households: Lee, S. Neighborhood walkability for subsidized households.

- Zeng, W.; Rees, P.; Xiang, L. Zeng, W.; Rees, P.; Xiang, L. Do residents of Affordable Housing Communities in China suffer from relative accessibility deprivation? A case study of Nanjing. Cities.

- Acolin, A.; Hoek-Smit, M.C.; Eloy, C.M. Acolin, A.; Hoek-Smit, M.C.; Eloy, C.M. High delinquency rates in Brazil’s Minha Casa Minha Vida housing program: Possible causes and necessary reforms. Habitat Int.

- Artioli, F. Artioli, F. Sale of public land as a financing instrument. The unspoken political choices and distributional effects of land-based solutions. Land Use Policy, 1051. [Google Scholar]

- Conteh, A.; Earl, G.; Liu, B.; Roca, E. Conteh, A.; Earl, G.; Liu, B.; Roca, E. A new insight into the profitability of social housing in Australia: A Real Options approach. Habitat Int. 1022. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, E.; De Wilde, P. Heffernan, E.; De Wilde, P. Group self-build housing: A bottom-up approach to environmentally and socially sustainable housing. J. Clean. Prod. 1186. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Hu, Z. Six types of government policies and housing prices in China. Econ. Model. 1057. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, Z; Altruism as a developer strategy of accumulation through affordable housing policy in Toronto and Vancouver: Giving back to get ahead.

- Lowe, J. S.; Prochaska, N; The potential of Community Land Trust and land bank collaboration: Keating, W.D. Bringing permanent affordable housing and community control to scale.

- MacAskill, S.; Sahin, O.; Stewart, R.; Roca, E.; Liu, B. MacAskill, S.; Sahin, O.; Stewart, R.; Roca, E.; Liu, B. Examining green affordable housing policy outcomes in Australia: A systems approach. J. Clean. Prod. 1262. [Google Scholar]

- MacAskill, S.; Mostafa, S.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O.; Suprun, E. MacAskill, S.; Mostafa, S.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O.; Suprun, E. Offsite construction supply chain strategies for matching affordable rental housing demand: A system dynamics approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 1030. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulic ́,J.;Vizek,M.;Stojcˇic ́,N.;Payne,J.E.;Cˇasni,A.Cˇ.;Barbic ́,T.Theeffectoftourismactivityonhousingaffordability. Ann. Tour. Res. 1032.

- Palm, J.; Reindl, K.; Ambrose, A. Palm, J.; Reindl, K.; Ambrose, A. Understanding tenants’ responses to energy efficiency renovations in public housing in Sweden: From the resigned to the demanding. Energy Rep. 2619. [Google Scholar]

- Reusens, P.; Vastmans, F.; Damen, S. Reusens, P.; Vastmans, F.; Damen, S. A new framework to disentangle the impact of changes in dwelling characteristics on house price indices. Econ. Model. 1062. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Xu, H.; Yu, J. Tan, J.; Xu, H.; Yu, J. The effect of homeownership on migrant household savings: Evidence from the removal of home purchase restrictions in China. Econ. Model. 1056. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Torres, C.E.; Gómez-Amador, A. Vázquez-Torres, C.E.; Gómez-Amador, A. Impact of indoor air volume on thermal performance in social housing with mixed mode ventilation in three different climates. Energy Built Environ.

- Voith, R.; Liu, J.; Zielenbach, S.; Jakabovics, A.; An, B.; Rodnyansky, S.; Orlando, A.W.; Bostic, R.W. Voith, R.; Liu, J.; Zielenbach, S.; Jakabovics, A.; An, B.; Rodnyansky, S.; Orlando, A.W.; Bostic, R.W. Effects of concentrated LIHTC development on surrounding house prices. J. Hous. Econ. 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera, R.; Verma, R. Jayaweera, R.; Verma, R. Are remittances a solution to housing issues? A case study from Sri Lanka. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open, 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell, G.; Newman, S.; Tarekegne, B.; Boff, D.; Fowler, R.; Gonzalez, J. Pennell, G.; Newman, S.; Tarekegne, B.; Boff, D.; Fowler, R.; Gonzalez, J. A comparison of building system parameters between affordable and market-rate housing in New York City. Appl. Energy, 1195. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman,M.A.U.;Ley,A.Micro-creditvs.Groupsavings–differentpathwaystopromoteaffordablehousingimprovementsin urban Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 1022.

- Tonn,B.;Hawkins,B.;Rose,E.;Marincic,M.Income,housingandhealth:PovertyintheUnitedStatesthroughtheprismof residential energy efficiency programs. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 1019.

- Bolívar,M.P.R.;Meijer,A.J.Smartgovernance:Usingaliteraturereviewandempiricalanalysistobuildaresearchmodel. Soc.Sci. Comput. Rev.

- HandbuchQualitativeForschunginderPsychologie; Munich: Mey,G.,Mruck,K.,Eds.;Beltz Psychologie Verl. Union.

- Adabre,M.A.;Chan,A.P.Criticalsuccessfactors(CSFs)forsustainableaffordablehousing. Build.Environ.

- Adabre,M.A.;Chan,A.P.;Darko,A.;Osei-Kyei,R.;Abidoye,R.;Adjei-Kumi,T.Criticalbarrierstosustainabilityattainmentin affordable housing: International construction professionals’ perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 1199.

- Ezennia,I.S.;Hoskara,S.O.Assessingthesubjectiveperceptionofurbanhouseholdsonthecriteriarepresentingsustainable housing affordability. Sci. Afr. 0084.

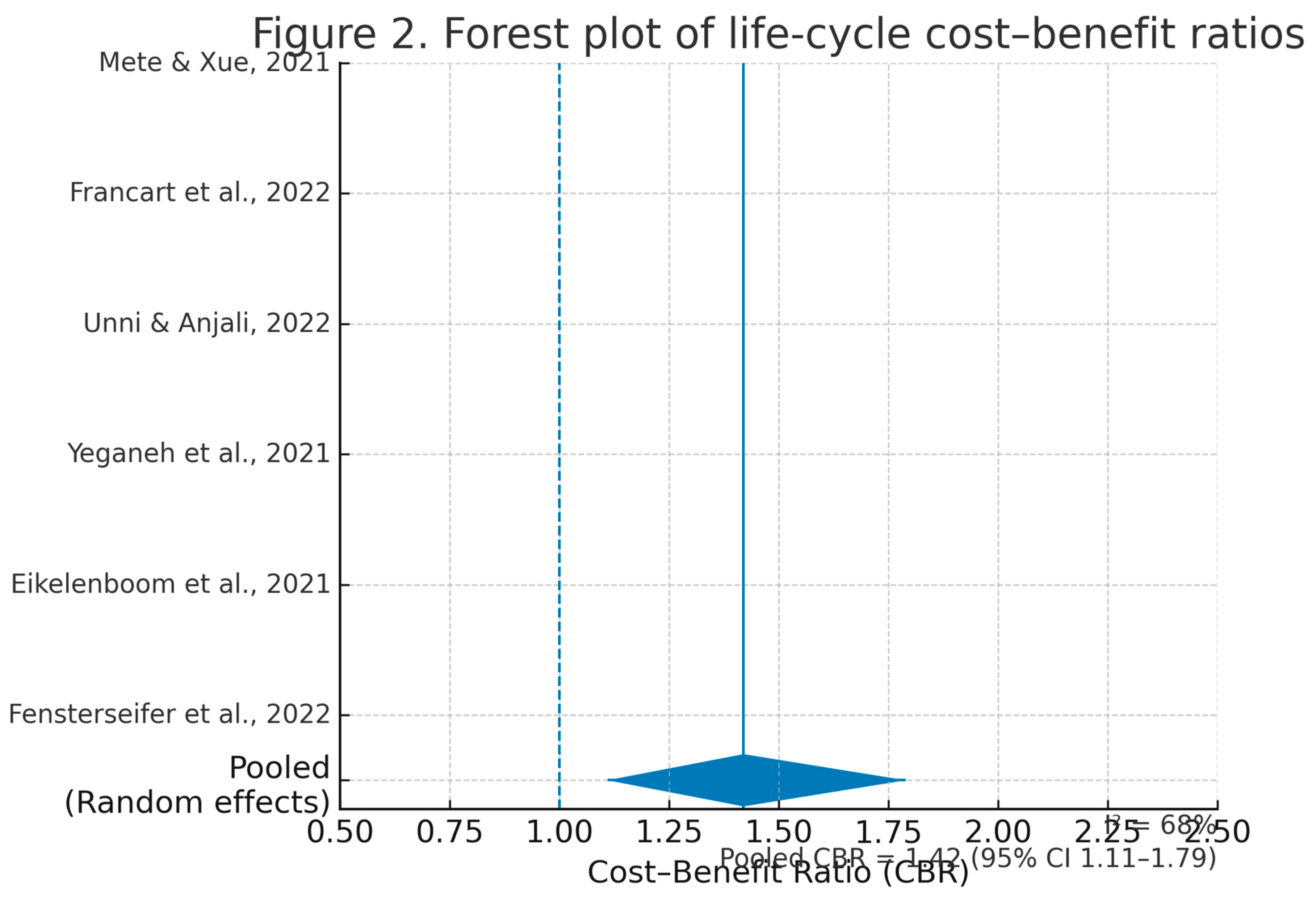

| Author & Year | Country/Region | Study Design | Population/Context | Sustainability Dimension(s) addressed | Key Findings |

| Chan & Adabre, 2019 | Ghana | Case study / Qualitative | Low-income urban households | Governance, Affordability | Identified institutional delays & barriers; emphasized critical success factors for sustainable affordable housing |

| Malik & Bardhan, 2020 | India (Mumbai) | Empirical evaluation | Low-income dwellings | Environmental, Affordability | Energy efficiency retrofits reduced thermal energy use by 35%; affordability improved only with subsidies |

| Francart et al., 2022 | Sweden | Empirical evaluation | Public housing projects | Building performance, Policy | Renovations improved energy efficiency by 40% while keeping tenant costs stable |

| Mete & Xue, 2021 | Switzerland | Cost-benefit analysis | Housing developments | Life cycle analysis, Affordability | Higher upfront costs recouped in 10–15 years via reduced operational costs |

| Fensterseifer et al., 2022 | Brazil | Case study | Affordable housing projects | Circular construction, Environmental | Green façades & recycled materials enhanced thermal comfort & reduced costs |

| zu Ermgassen et al., 2022 | UK | Policy analysis | National housing policies | Governance, Environmental, Urban planning | Biodiversity net gain strategies linked ecological and housing goals |

| Cubillos-González & Cardoso, 2021 | Latin America | Policy / Governance study | Urban affordable housing | Urban planning, Governance | Found governance fragmentation limits sustainability integration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).