2. Methods

2.1. Animals

For the investigation, a group of forty male albino Wistar rats, with an average weight of 157 g, was obtained from the University of Ibadan. They were housed in standard cages at the animal facility of the Biochemistry department, University of Ibadan. Before the study, the rats were acclimated to the study environment, provided with a regular rat diet, and given unrestricted access to water. During this adaptation period, the rats were maintained under consistent conditions, including a temperature of 22 ± 2°C, a 12-hour light-dark cycle, and continuous access to food and water. All procedures adhered to the guidelines approved by the University of Ibadan Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee (UI-ACUREC), with approval number UI-ACUREC/057-1222/11.

2.2. Chemicals

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of the highest quality and were obtained commercially from accredited distributors. See

Table 1 for a list of chemicals used in this study.

2.3. Experimental Protocol

Forty male Wistar rats were divided into five groups, each consisting of eight animals.

Group 1: Control cohort (allowed free access to distilled water daily).

Group 2: HgCl2 only cohort: (20 µg/L HgCl2 dissolved in the drinking water).

Group 3: TQ only cohort: (TQ 5 mg/kg bw per os /day).

Group 4: HgCl2 + TQ (Low dose TQ) cohort: (20 µg/L HgCl2 dissolved in drinking water + 2.5 mg/kg bw of TQ per os /day).

Group 5: HgCl2 + TQ treated rats (High dose) cohort (20 µg/L of HgCl2 dissolved in drinking water + 5 mg/kg bw of TQ per os /day).

The doses were chosen based on previous studies from the scientific literature (Boujbiha et al., 2009; Moradi Maryamneghari et al., 2021). The substances were administered to non-fasted rats in the morning (between 09:00 and 10:00 h). The first day the animals were treated was considered experimental Day 0. At the end of the 4th week (28 days) of treatment, all animals were sacrificed and dissected. The testis, epididymis and hypothalamus tissues were quickly removed for biochemical and histological examinations.

Figure 1.

Experimental design on the effect of Thymoquinone on mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar Albino rats for 28 days. Created with

https://app.biorender.com/ by Uche Arunsi.

Figure 1.

Experimental design on the effect of Thymoquinone on mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar Albino rats for 28 days. Created with

https://app.biorender.com/ by Uche Arunsi.

2.4. Study Conclusion and Euthanasia

Twenty-four hours following the final administration, the rats' final body weights were recorded, and blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus using plain tubes before euthanasia through cervical dislocation after carbon dioxide asphyxiation. The animals were carefully restrained, and a sterile microcapillary tube was gently inserted into the retro-orbital venous plexus behind the eye. Blood was cautiously aspirated into labelled plain sample bottles. After removing the microcapillary tube, the collected blood was allowed to clot. Serum samples were obtained by centrifuging the clotted blood at 3000 g for 10 minutes. Subsequently, the serum samples were frozen at −20 °C until hormone assays were performed using ELISA diagnostic kits (Amersham, UK). The hypothalamus, testes, and epididymis were promptly excised, weighed, and processed for biochemical and histological analyses. The organo-body weight indices (OBWI) of the hypothalamus, testes, and epididymis were determined using the formula OBWI = 100 × organ weight (g)/body weight (g). The tissues of interest were dissected and washed in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2, 4℃). Post-washing, samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. The tissues were homogenised using a Teflon homogeniser (Heidolph Silent Crusher M), and the homogenates were subsequently centrifuged. The protein content of the supernatant was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951), utilising bovine serum albumin as the standard.

2.5. Assessment of Sperm Progressive Motility

Sperm progressive motility was assessed using the method described by Zemjanis (Zemjanis et al., 1970). The cauda epididymis was cut with surgical blades, releasing sperm onto a sterile glass slide. The sperm was then diluted with a pre-warmed 2.9% sodium citrate dehydrate solution at 37 °C, mixed carefully, and covered with a coverslip (24 × 24 mm). Sperm motility was evaluated by examining at least ten microscopic fields under a phase contrast microscope at 200× magnification. The sperm in the same field were categorised based on their motility as progressive, non-progressive, or immotile. The result was expressed as a percentage of sperm progressive motility.

2.6. Assessment of Epididymal Sperm Count

The epididymal sperm count method follows WHO guidelines (1995). The cauda epididymis is crushed in saline, filtered through nylon mesh, and a 5 μL sample of the suspension is mixed with 95 μL of diluent. After placing 10 μL of the diluted sperm on a hemocytometer and letting it sediment for 5 minutes, sperm cells are counted using an improved Neubauer chamber (Deep 1/10 m; LABART, Munich, Germany) under a light microscope at 400x magnification.

2.7. Assessment of Sperm Morphological Abnormalities and Viability Assay

Sperm viability and morphological abnormalities were evaluated using Wells and Awa's method (1970). Sperm smears were prepared on clean slides. Viability was assessed with 1% eosin and 5% nigrosine in a 3% sodium citrate solution. At least 400 sperm cells per rat were examined for morphological abnormalities by staining with 0.2 g of eosin and 0.6 g fast green, dissolved in distilled water and ethanol (2:1). The percentages of head, mid-piece, and tail abnormalities were recorded for both control and treated rats.

2.8. Assessment of Reproductive Hormone Levels

Serum concentrations of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating Hormone (FSH), prolactin, and testosterone were quantified utilising ELISA plates procured from Elabscience Biotechnology (Wuhan, China), adhering to the manufacturer's protocols. The detection limits of the hormonal assays were established at 0.54 ng/ml for LH, 0.28 ng/ml for FSH, 0.39 ng/ml for prolactin, and 0.58 ng/ml for testosterone. All hormone measurements were performed concurrently to minimise inter-assay variability, with minimal intra-assay coefficients of variation recorded as 2.9%, 3.3%, 2.4%, and 3.8% for FSH, LH, prolactin, and testosterone, respectively.

2.9. Assessment of Testicular Enzyme Function

Acid and alkaline phosphatase (ACP and ALP) activities in the testicular supernatant were assessed using protocols involving p-nitrophenyl-phosphate hydrolysis under acidic (Vanha-Perttula & Nikkanen, 1973) and alkaline (Malymy & Horecker, 1966) conditions. Testicular glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity was determined using NADP+ and glucose-6-phosphate as substrates, following a modified method based on Wolf et al., 1987. Lactate dehydrogenase-X (LDH-X) activity was evaluated according to Vassault's protocol (Owumi, Otunla, et al., 2022; Vassault, 1983), involving the inter-conversion of pyruvate and lactate.

2.10. Evaluation of Biomarkers of Testes, Epididymis and Hypothalamus Antioxidant Status

The testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus samples from the experimental rats were homogenised in phosphate buffer (0.05 M; pH 7.4). The tissue homogenates were then centrifuged (12,000 × g; 15 min; 4°C) to obtain a clear supernatant, which was collected into appropriately labelled vials for the assessment of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. The protein concentrations in the testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus were analysed using Lowry's method (Lowry et al., 1951). The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured using the procedure described by Misra and Fridovich (Misra & Fridovich, 1972), while the activity of the catalase (CAT) enzyme was determined using Clairborne's method (Clairborne, 1995). The protocols outlined by Habig (Habig et al., 1974) and Rotruck (Rotruck et al., 1973) were employed to assess the enzyme activities of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels were measured using the methods of Beutler (Beutler et al., 1963), and total sulfhydryl groups (TSH) levels were determined via the Jollow et al. method (Jollow et al., 1974). Additionally, biomarkers of cellular response to oxidative stress in the testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus of experimental animals, specifically NRF-2, HO-1, along with TRX levels and TRX-R activity, were assayed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits specific for rats, following the manufacturer’s protocol as previously reported (Owumi et al., 2023; Owumi et al., 2022).

2.11. Evaluation of RONS & LPO levels and XO activity in the Testes, Epididymis and Hypothalamus of Rats

An established method based on the RONS-dependent oxidation of 2' 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) to dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was used to assess the RONS production in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus (Perez-Severiano et al., 2004). Lipid peroxidation was determined by measuring the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) present in the test sample according to the method of Okhawa (Ohkawa, 1979). Malondialdehyde (Badary et al.), formed when fatty acids are peroxidised, combines with the chromogenic agent 2-thiobarbituric acid in an acidic condition to form a pink-coloured complex with a maximum absorbance at 532 nm that may be extracted using an organic solvent like butanol. The result is presented as the amount of free MDA generated, since MDA is frequently used to calibrate this test. A sample was prepared using 40 μL of the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus and was combined with 50 μL of 30% TCA in 160 mL of Tris-KCl buffer. Then, 50 L of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) at 0.75% was added and incubated for 45 min at 80 °C. The mixture was centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 minutes after being cooled to 25 °C. A microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance of 200 μL of the clear supernatant compared to a reference blank of distilled water at 532 nm. The method of Bergmeyer et al. (Bergmeyer et al., 1974) was used to assess the activity of xanthine oxidase (XO) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus. As uric acid is created from xanthine by the enzyme XO, the assay depends on the measurement of uric acid absorbance at 290 nm. 8 µL of the sample, 150 µl of phosphate buffer, and 80 µL of xanthine solution were pipetted into a microplate. After mixing, 290 nm absorbance measurements were made every minute for three minutes and read against a blank, which was created by substituting 8 µL of the sample with distilled water.

2.12. Evaluation of Pro-Inflammatory Markers in the Testes, Epididymis and Hypothalamus of Rats

Nitric oxide (NO) levels in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus samples were assayed following Green’s method (Green et al., 1982). Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a biomarker of polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation, was measured using a modified version of the Trush method that was previously published (Trush et al., 1994). MPO oxidises o-dianisidine in the presence of H2O2 to produce a brown-colored molecule with a 470 nm absorbance. Additionally, testicular, epididymal and hypothalamic IL-1β were assessed using SpectraMax Multimodal plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) and commercially available ELISA Kits, as the manufacturer's guide instructed.

2.13. Evaluation of Apoptosis Biomarkers

Using ELISA Kits from Elabscience (Beijing, China) and following the instructions in the manufacturer's manual, the activity and concentrations of testicular, epididymal and hypothalamic Bcl-2 Associated X Protein (Bax), B-cell Lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), and protein 53 (P53) were determined. Seven microplate wells were filled with 100 μL of the standard working solution, and the remaining wells were filled with 100 μL of testes, epididymis and hypothalamus homogenates. The plate was sealed with the kit's sealer and left in a water bath at 37 °C for 90 minutes. Following the incubation period, each well's liquid was drained without being washed, and 100μl of biotinylated detection Ab working solution was added immediately. The plate was then gently mixed, covered with a plate sealer, and incubated for a further hour at 37 °C. Then, 350 μL of wash buffer was added, the solution from each well was decanted, and the wells were allowed to soak for 1-2 minutes before being decanted and dried against clean absorbent paper. Following the washing procedure, 90μl of substrate reagent was added to each well in the dark, the plate was sealed, and the mixture was then incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. The M384 SpectraMaxTM Multimodal plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) was then used to measure the OD value at 450 nm immediately after the reaction was stopped by adding 50 µL of stop solution to each well. The amount of Bax, Bcl-2 and P53 in the samples directly relates to how intense the colour developed.

2.14. Histopathological Examination of the Testes, Epididymis and Hypothalamus

Microscopic examination of the assessed testes, epididymis and hypothalamus sections was performed following the method of Bancroft & Gamble (Bancroft & Gamble, 2008). Properly removed and treated with 10% formalin solution were the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus. Following the dehydration processes, the sections were paraffin-embedded. The tissues were divided into sections (4-5 μm slices) using a microtome, then transferred to charged slides and stained using the conventional hematoxylin and eosin stain. A Carl Zeiss Axio light microscope was used to examine the coded tissue slides. A Zeiss Axiocam 512 camera affixed to the microscope was utilised by a pathologist unfamiliar with the various treatment groups from which the slides were taken to record representative images during the assessment.

2.15. Molecular Docking Method

Molecular docking was conducted to assess the interaction between TQ and PPAR-α or PPAR δ/β. The molecular docking scores, reflecting the binding affinity between the ligand and the proteins, were quantified as binding constants (Kd). To achieve this, the 3-D structures of TQ were sourced from PubChem:

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, while the structures of the PPAR-α (PDB: 1I7G) and PPAR- δ/β (PDB: 3D5F) were acquired from the Protein Database (PDB):

https://www.rcsb.org/. Protein preparation was done using UCSF ChimeraX (Meng et al., 2023). Additionally, the ligand (TQ) from the synthesised receptors was loaded into PyRx, and Open Babel was employed for energy minimisation. Following this, molecular docking was conducted using grid boxes designed around the position of the co-crystallised ligand. The docking modes that exhibited the lowest Gibbs free energy were then visualised with PyMol. The binding constant (Kd) was estimated from the general information ΔG = -RTInKd, where R: Gas constant = 0.001987kcal/mol/K, T: Temperature in Kelvin = 298K, G: Gibbs free energy.

2.16. Statistical Analysis

The study's data were analysed using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 for Windows (

www.graphpad.com; GraphPad, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post-hoc test (Bonferroni) were used to compare the means of a group with the mean of another.

p<0.05 was selected for statistically significant differences. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD of the replicates.

4. Discussion

Exposure to heavy metals such as mercury has been shown to cause abnormalities in the reproductive system, potentially leading to infertility or subfertility in males (Henriques et al., 2019). This paper aims to investigate the effectiveness of thymoquinone (TQ), an antioxidant with anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties, in protecting the hypothalamic-gonadal axis of male mice from mercuric chloride (HgCl2)-induced toxicity.

Evaluating body and organ weights is vital for assessing toxicity, as changes in these indices may indicate physiological disturbances in animals (Lazic et al., 2020). In this study, exposure to HgCl

2 reduced body weight gain, organ weight, and relative organ weight of the reproductive tissues, as shown in

Table 2. A reduction in body weight is symptomatic of mercury toxicity, which is often associated with loss of appetite in experimental animals (Shalan, 2022). This observation is in line with other research that reported insignificant changes in body and organ weights upon HgCl

2 administration. However, administration of TQ restored body and organ weights in experimental rats, suggesting its protective effect.

Sperm quality, including parameters such as motility, count, viability, and morphology, is a crucial measure of male fertility in toxicological studies (Tanga et al., 2021). In this study, HgCl

2 exposure significantly reduced sperm motility by approximately 27.78% relative to controls, highlighting its adverse effects (

Table 3). Sperm motility is essential for fertilisation capabilities, and a decline of 27.78% could jeopardise this function (

Table 3). This finding aligns with previous research indicating that HgCl

2 impairs sperm membrane integrity and induces morphological defects (Martinez et al., 2017).

Additionally, a significant reduction was observed in sperm count following HgCl

2 exposure, with a 25.60% decrease compared to controls, indicating adverse effects on male fertility. Reduced sperm count can lower the chances of successful fertilisation, according to Dabbagh Rezaeiyeh et al. (2022), who found similar results where HgCl

2 disrupted germinal epithelium, reducing sperm production (Jahan et al., 2019). Interestingly, semen volume remained consistent across all groups (

Table 3), suggesting that while HgCl

2 affects spermatogenesis, it does not appear to impact seminal fluid production or ejaculation volume. This observation contrasts with results from Altunkaynak et al. (2015), who noted a reduction in sperm volume when treating rats with elemental mercury (Hg

0) as opposed to HgCl

2.

While the changes in morphological abnormalities of the sperm between groups post-HgCl

2 exposure were insignificant, subtle alterations in sperm morphology can affect their functionality (Moretti et al., 2022),

Table 3. The minor increases in abnormalities across the headpiece, midpiece, and tail, albeit statistically insignificant, hint at possible disruptions in spermiogenesis – the final stages of sperm maturation. Previous studies outlined mercury's ability to induce sperm DNA damage (Jahan et al., 2019; Wyatt et al., 2017), which might be corroborated by these observed morphological perturbations. Nevertheless, TQ administration was observed to insignificantly increase sperm morphological and functional parameters in this study

Table 3. This result contradicts prior findings, where TQ showcased commendable recuperative actions against various sperm parameter toxicities in rats (Altunkaynak et al., 2015). The subtle increases in morphological abnormalities even post-TQ treatment, especially in the 5.0 mg/kg co-treatment group, might suggest that TQ's protective mechanisms do not entirely circumvent the structural disruptions instigated by mercury.

A complex network of hormones regulates the male reproductive system, including LH, FSH, testosterone, and prolactin (Sokwala, 2021). These hormones are produced in the testes and pituitary glands and are responsible for various functions such as sperm production, sex drive, and secondary sexual characteristics (Sadiq & Tadi, 2024). LH and FSH stimulate the production of testosterone, which is essential for developing and maintaining male reproductive and accessory reproductive organs (Sadiq & Tadi, 2024). Prolactin, on the other hand, plays a role in suppressing the production of LH and FSH, which can lead to a decrease in testosterone levels (Sadiq & Tadi, 2024). The significant diminutions in serum LH, FSH, and testosterone levels upon exposure to HgCl

2 corroborate the reports delineated by earlier investigations, where HgCl2's toxicological profile encompassed reproductive harm (Albasher et al., 2020; Sampada & David, 2024),

Figure 2. A decline in LH and FSH levels, the primary regulators of spermatogenesis and testosterone synthesis, hints at potential disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis

Figure 2. A concomitant reduction in testosterone, a pivotal steroid for maintaining male secondary sexual characteristics, sperm production, and libido, provides evidence of this compromised HPG axis, potentially underscoring reduced Leydig cell functionality or disrupted feedback mechanisms. Conversely, the surge in prolactin levels post-HgCl

2 exposure presents an intriguing conundrum. In a male physiological context, elevated prolactin can suppress LH and FSH secretion, potentially contributing to the observed declines in these hormones and, by extension, testosterone (Petersenn et al., 2023).

In contrast, co-treatment with TQ (2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg) demonstrated recuperative actions by mitigating the hormonal aberrations induced by HgCl

2. This normalisation of hormonal levels, particularly testosterone restoration and prolactin reduction, underscores TQ’s potential in safeguarding male rats’ endocrine system

Figure 2. These findings are consistent with previous research where TQ was shown to counteract heavy metal-induced endocrine and reproductive derangements (Hassan et al., 2019). Furthermore, the dose-dependent effectiveness of TQ is evident, as the elevated dose (5.0 mg/kg) results in more pronounced rectifications (515.08%), underscoring its potential therapeutic range. This finding supports the hypothesis that TQ may influence at various levels—shielding testicular Leydig cells, revitalising the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, and potentially directly modulating steroidogenic enzymes.

Mercury's disruptive influence on the reproductive system, particularly on the testes, has been a focal point of numerous scientific inquiries in recent years (Henriques et al., 2019). Due to its pivotal role in spermatogenesis, the testicular tissue is a highly metabolically active site, relying on specialised enzymes to maintain its structure and function. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) plays a role in phosphate metabolism and membrane transport, supporting germ cell development and maturation within the seminiferous epithelium (Sekaran et al., 2021). Acid phosphatase (ACP), primarily a lysosomal enzyme, is involved in sperm maturation. At the same time, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is essential for energy metabolism in spermatogenic cells, supporting sperm motility and viability through anaerobic glycolysis (Rotimi et al., 2024). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) contributes to redox homeostasis by generating NADPH, which protects testicular cells from oxidative damage and supports steroidogenic activity in Leydig cells (Chen et al., 2022). The current study observed a significant (p<0.05) diminution in the testicular enzymatic activities of ALP, ACP, LDH, and G-6-PD upon exposure to HgCl

2 Figure 3. The significant decline in the enzymatic activities of ALP and ACP, which are closely associated with spermatogenic activity and testicular cellular function, indicates the potential compromise of sperm maturation processes upon HgCl

2 exposure

Figure 3. Similarly, the downturn in LDH, a crucial enzyme for cellular energetics, and G-6-PD, central to redox balance, alludes to a dual blow: an energetic crisis and heightened vulnerability to oxidative perturbations. This complements the findings of Jahan et al. (2019), where mercury exposure translated into compromised sperm production and amplified oxidative damage. Conversely, TQ, especially at the higher dose (5.0 mg/kg), alleviated the HgCl

2-induced enzyme activity reductions and augmented them to levels surpassing those seen in controls

Figure 3. This resonates with the earlier findings about TQ's protective role against drug and heavy metal-induced reproductive damages (Hassan et al., 2019; Moradi Maryamneghari et al., 2021). Testicular cells, particularly spermatogenic and Leydig cells, are susceptible to oxidative stress, which can impair enzyme function and reduce fertility (Monageng et al., 2023). TQ scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and upregulates endogenous antioxidant defence systems, preserving the structural integrity and function of testicular tissues. By mitigating lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage in the testes, TQ helps restore or enhance the activity of these testicular enzymes.

A consistent theme across studies on mercury toxicity is the perturbation of oxidative balance (Albasher et al., 2020; Boujbiha et al., 2009; Jahan et al., 2019). In this study, a significant (p<0.05) decline in the activities of CAT, SOD, GST, and GPx was observed in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, reflecting the adverse impact of HgCl

2 on the enzymatic antioxidants of the male rats’ reproductive tissues. The disruption of these enzymes signifies an overwhelmed oxidative defence system, rendering the cells vulnerable to oxidative damage. This aligns with the established understanding that HgCl

2 stimulates the production of ROS, which, in turn, can cause cellular damage, inflammation, and apoptosis, central to mercury's reproductive toxicity (Almeer et al., 2020; Kandemir et al., 2020). Furthermore, the reduction in glutathione (GSH) and total sulfhydryl (TSH) levels indicates depleted cellular thiols

Figure 6. GSH, a tripeptide, is fundamental in cellular defence against oxidative stress, and its depletion is a well-recognised marker of cellular oxidative damage (Narayanankutty et al., 2019). However, findings from this study demonstrate the protective effects of TQ as co-treatment with TQ, specifically at higher doses (5 mg/kg), significantly elevated the antioxidant enzymes and compounds initially suppressed by HgCl

2 Figure 6. This result suggests that TQ might be acting by scavenging the ROS produced, upregulating the antioxidant defence genes, or both. The notable increase in GST activity, especially in the epididymis and hypothalamus following TQ co-treatment, emphasises its role in detoxification. GST is known to conjugate GSH to various electrophilic compounds, aiding their removal and neutralisation (Laborde, 2010). Therefore, the increased activity indicates a mechanism where TQ potentially induces GST expression or provides the necessary cofactors to optimise its activity.

Furthermore, the oxidative stress-inducing ability of HgCl

2 is evident from the significant (p<0.05) increases in biomarkers of oxidative damage across the testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus of the exposed rats, specifically, RONS, LPO, and Protein Carbonyl levels and XO activity (Erboga et al., 2016),

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. These findings are consistent with previously established data, where mercury exposure is associated with an imbalance of the oxidative balance in the reproductive tissues of rats (Albasher et al., 2020; Boujbiha et al., 2009; Jahan et al., 2019). The rise in LPO levels, a marker of cellular lipid membrane damage, underscores the direct damage inflicted on cellular structures by ROS. Elevated levels of LPO are indicative of compromised membrane integrity and function, potentially leading to cellular dysfunction and death (Pardillo-Diaz et al., 2022). Similarly, the surge in XO activity, an enzyme that catalyses the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine, further contributes to ROS generation and consequently intensifies oxidative stress (Battelli et al., 2016).

Additionally, the increase in RONS further corroborates the notion of heightened oxidative and nitrosative stress upon HgCl

2 exposure. Contrastingly, TQ significantly (p<0.05) protected the examined tissues from HgCl

2-induced oxidative damage

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The protective effects of TQ, particularly at higher doses, resonate with its previously documented antioxidant (Algaidi et al., 2022; Mabrouk & Ben Cheikh, 2015). It appears that TQ either directly scavenges the free radicals generated by HgCl

2 exposure or upregulates the cellular antioxidant defence system, thereby restoring the oxidative balance. The significant reduction in LPO, XO, and RONS in the testes upon TQ co-treatment suggests an amelioration of HgCl

2-induced cellular and enzymatic damages. This has profound implications for male fertility, as the testes are pivotal for sperm production, the epididymis for sperm maturation and storage, and the hypothalamus for regulating numerous physiological functions, including reproductive hormone synthesis. Oxidative stress in these organs can compromise spermatogenesis, reducing sperm count, motility and increasing sperm abnormalities (Algaidi et al., 2022; Mabrouk & Ben Cheikh, 2015). However, the attenuation of oxidative markers in the epididymis suggests that TQ might preserve the structural and functional integrity of maturing sperm, ensuring their viability and motility and preserving endocrine homeostasis under oxidative insults.

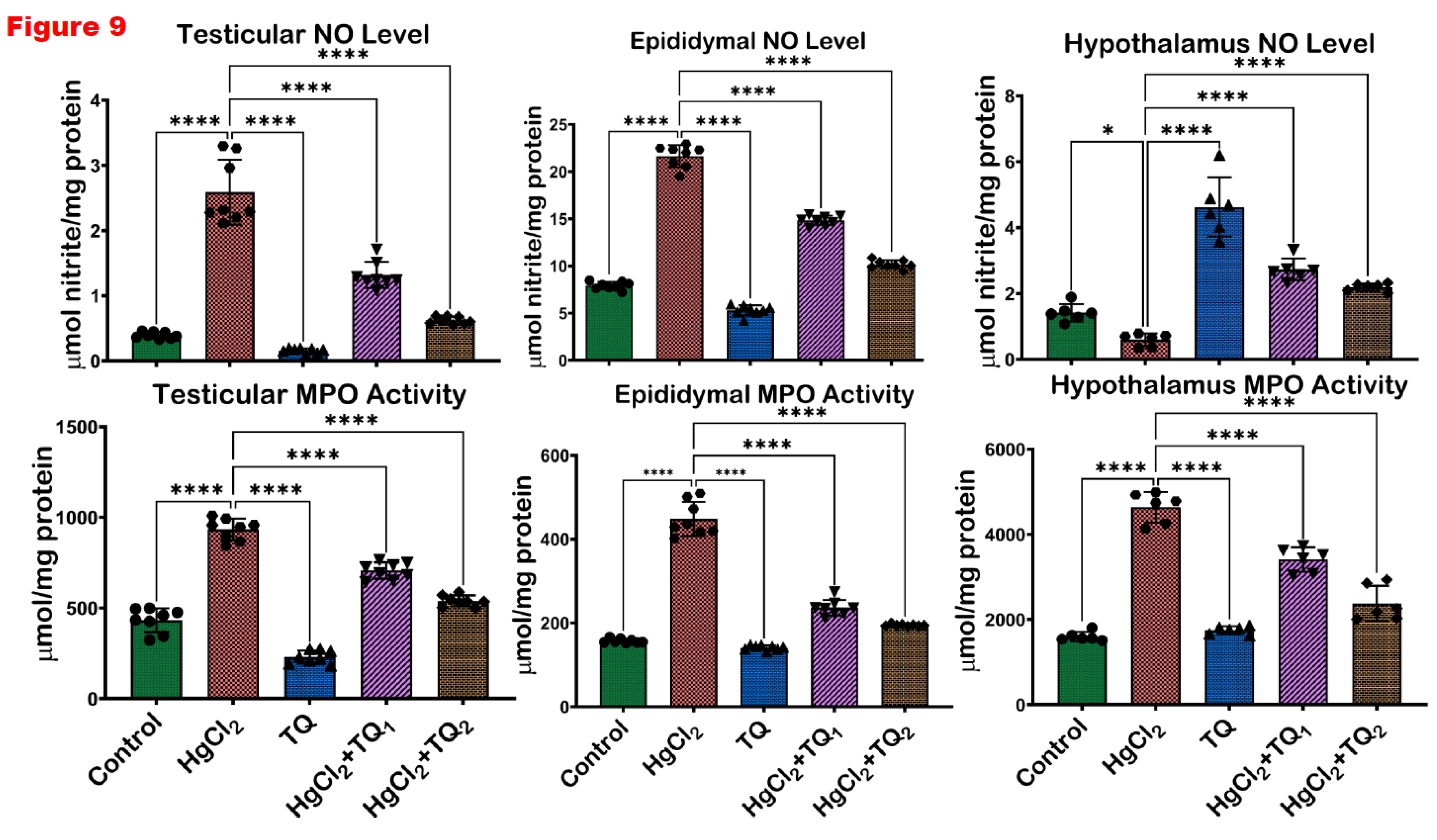

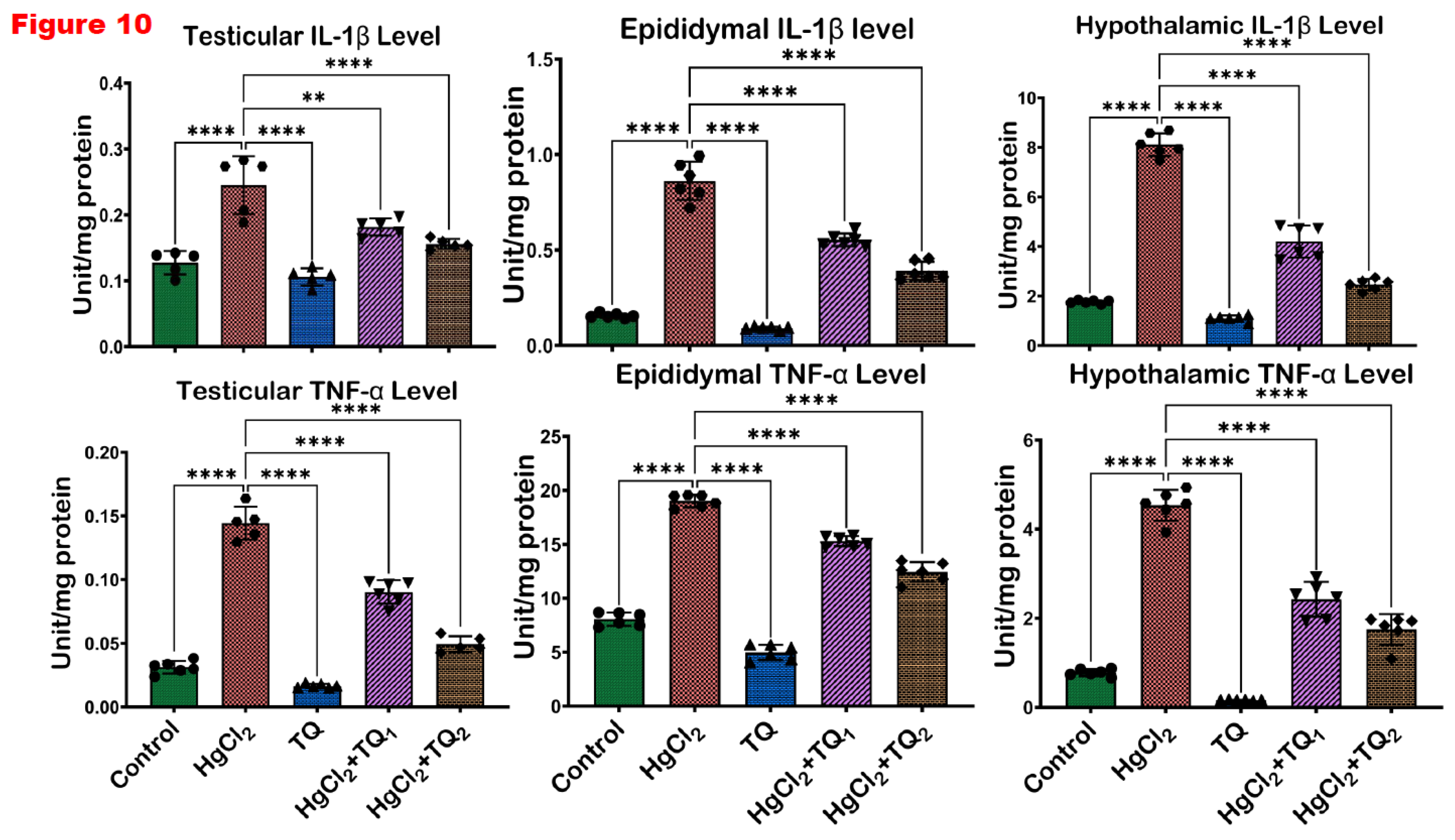

It is evident from previous work that damaged cellular components, as a result of oxidative stress, can act as danger signals or "alarmins" which are recognised by specific receptors on immune cells, leading to the activation of various inflammatory pathways (Vona et al., 2021). Also, lipid peroxidation products can activate the nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptors (NOD), leucine-rich repeats (LRR), and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, resulting in the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β (Gora et al., 2021). Moreover, ROS can directly activate transcription factors such as NF-κB, which plays a central role in the expression of genes responsible for inflammatory responses (Khan et al., 2021). Therefore, the sustained oxidative stress, as is potentially caused by HgCl

2 exposure, can perpetuate a chronic inflammatory state in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus. Inflammation, depending on the duration, is a two-edged sword. While acute inflammation is protective and aids tissue repair, chronic or persistent inflammation is detrimental and has been implicated in many pathological conditions, including reproductive dysfunctions (Soliman & Barreda, 2023). In this study, a pronounced inflammatory response was observed in the testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus upon HgCl

2 administration, as evidenced by the elevation in inflammatory markers, NO, MPO, IL-1β, and TNF-α (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Although a crucial signalling molecule in numerous physiological processes, NO can react with superoxide radicals at elevated levels to form peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant that can induce cellular damage (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2020). The significant upsurge in NO post-HgCl

2 exposure indicates the oxidative and nitrative stress inflicted on the examined tissues. The concomitant rise in pro-inflammatory cytokines observed in the current study, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and the myeloperoxidase marker of neutrophil infiltration, suggests an active inflammatory process (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

The increase in protein carbonyl levels further highlights oxidative protein damage, potentially compromising proteins' structural and functional integrity within the testes. Additionally, the significant increase in IL-1β levels, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, coupled with the elevation in other inflammatory markers (NO and MPO), suggests an epididymal environment that may not be conducive to sperm maturation and might compromise sperm motility and function. Moreover, chronic inflammation in the hypothalamus can potentially disrupt hormonal homeostasis, affecting downstream reproductive processes like hormone production and other vital functions regulated by this brain region (Sheng et al., 2020). This inflammatory and oxidative milieu can impair spermatogenesis, reduce testosterone synthesis, and affect overall testicular health. On the flip side, co-administration of TQ effectively counteracted the HgCl2-induced inflammation in rats' testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus. The higher dose (5.0 mg/kg) manifested more pronounced effects, suggesting a dose-dependent protective role of TQ. TQ has been shown to exert an anti-inflammatory effect via its inhibition of inflammatory cytokines and processes, such as TNF-α, inducible NOS, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), 5-lipoxygenase, and cyclin D1 (Fouad & Jresat, 2015). TQ also modulates the nuclear factor-κΒ and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways, which regulate inflammation and cell proliferation (Leong et al., 2021).

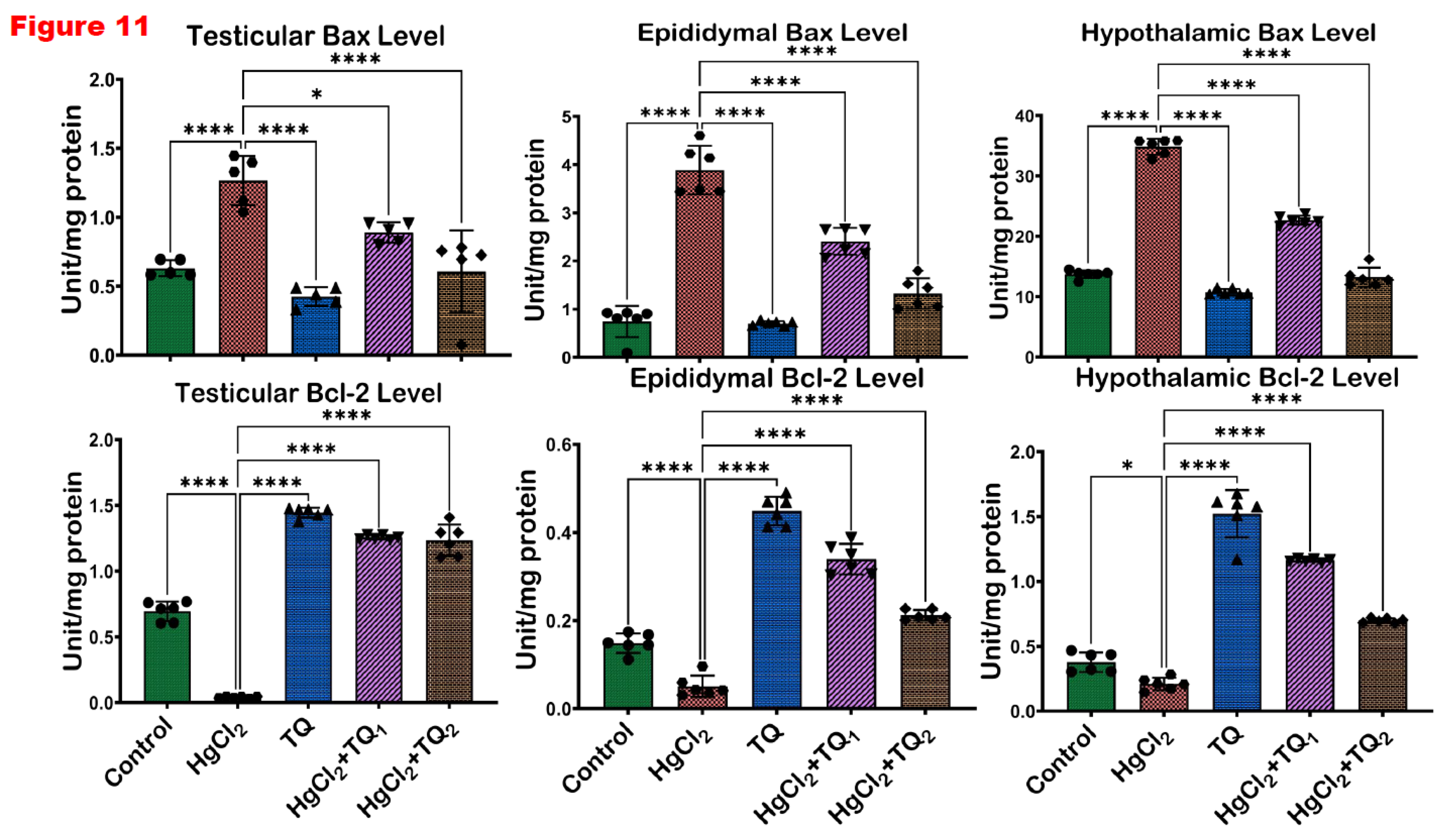

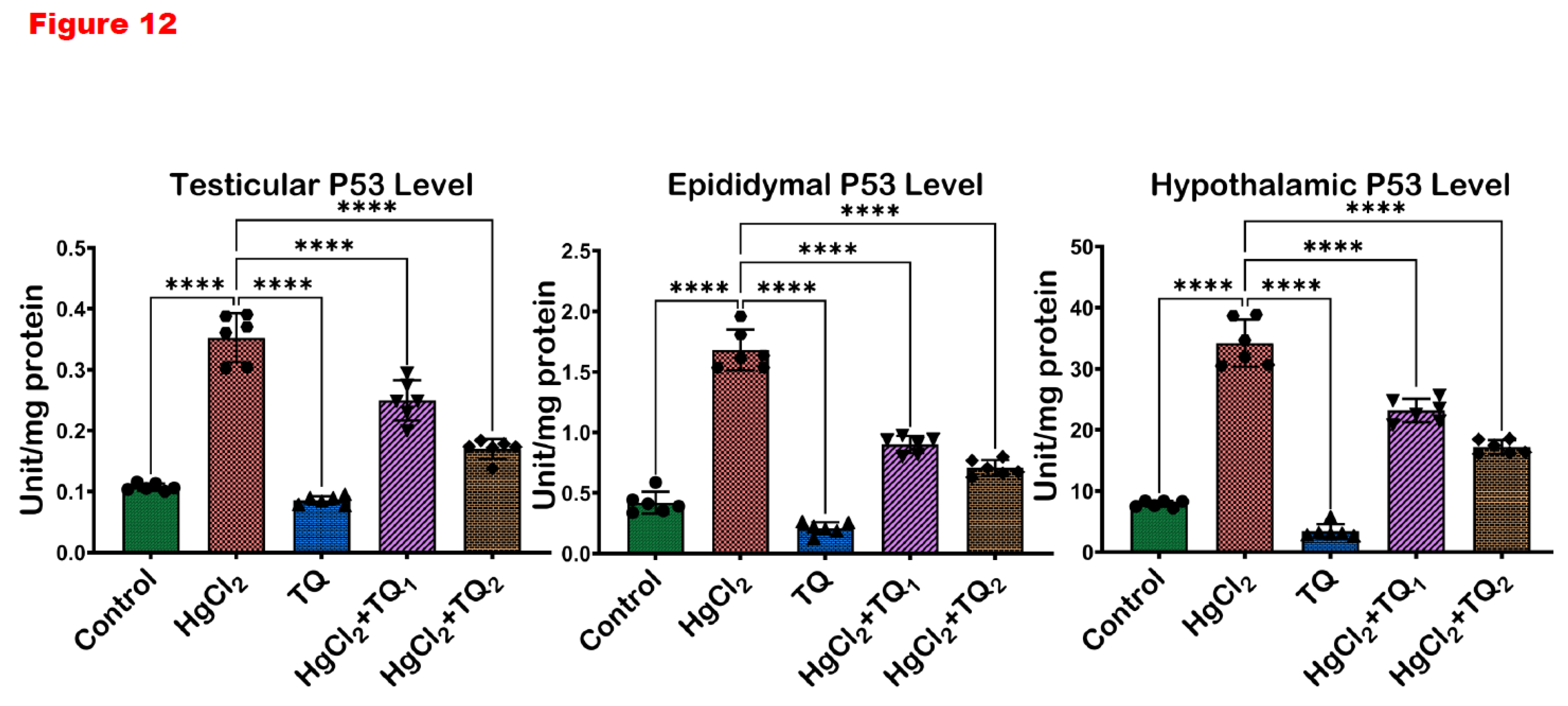

Apoptosis is an essential physiological process that ensures cellular homeostasis by removing damaged or unnecessary cells; the balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic molecules determines cellular fate (Singh et al., 2022). Bax (Bcl-2-associated X protein) induces the permeabilisation of the mitochondrial outer membrane, releasing cytochrome c into the cytosol (Singh et al., 2019). Once released, cytochrome c triggers a cascade of events culminating in cell death, making Bax a pro-apoptotic protein. Bax forms pores or channels in the mitochondrial membrane, facilitating the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors (Singh et al., 2019). On the other hand, B-cell lymphoma 2 or Bcl-2 prevents the permeabilisation of the mitochondrial membrane and subsequent release of cytochrome c by forming heterodimers with Bax, thereby inhibiting cell death (Edlich, 2018). P53 is a tumour suppressor protein that regulates cellular responses to stress and DNA damage (Vaddavalli & Schumacher, 2022). It is a transcription factor that activates genes involved in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, and apoptosis. This transcription factor promotes cell death by upregulating the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, including Bax, while simultaneously repressing anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2 (Shen et al., 2023). By modulating the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors, p53 helps to eliminate cells with irreparable DNA damage or those at risk of becoming cancerous, thus earning it the title "guardian of the genome (Vaddavalli & Schumacher, 2022)."

Additionally, p53 can directly induce apoptosis through transcription-independent mechanisms, such as interacting with pro-apoptotic proteins or promoting mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation (Shen et al., 2023). The significant decrease in Bcl-2 expression observed in the HgCl

2-alone group across the testes, epididymis, and hypothalamus signifies the potent ability to induce apoptosis

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. Since Bcl-2 is vital in inhibiting apoptosis, its reduction would predispose cells to death, possibly accounting for the observed pathological changes and functional impairments in the reproductive tissues and the regulatory centre (hypothalamus). Concomitantly, the substantial upregulation of Bax and P53 upon HgCl

2 exposure underscores the activation of apoptotic pathways. Bax initiates the intrinsic apoptotic cascade by promoting the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, while P53 facilitates apoptosis in response to DNA damage (Vaddavalli & Schumacher, 2022). The protective role of TQ was evident, as shown in the significant increase in Bcl-2 expression across all tissues upon TQ co-administration, implying that TQ can bolster cellular defences against apoptosis

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, thereby promoting cell survival. This is particularly crucial in the testes, where preserving the population of various cells, including the sperm-producing germ cells and testosterone-producing Leydig cells, is imperative for maintaining reproductive health. In the epididymis, safeguarding cells ensure optimal conditions for sperm maturation, and in the hypothalamus, neuronal survival is essential for endocrine and physiological regulation (Erboga et al., 2016; Sheikhbahaei et al., 2016).

Additionally, the concurrent reduction in Bax and P53 expressions upon TQ treatment in all tissues suggests that TQ can block the apoptotic signals induced by HgCl2. This observation concurs with earlier studies (Adinew et al., 2022; Homayoonfal et al., 2022). The significant downregulation of these pro-apoptotic molecules indicates that TQ potentially prevents the cellular cascades that culminate in apoptosis, safeguarding cellular integrity and function.

Our histomorphometry findings are consistent with our result on sperm morphology, which showed atrophy of the testicular tubules with a disarranged germ cell layer and vacuolation of Sertoli cells, which confirm impairment in spermatogenesis and degenerated germinal epithelium of the epididymis confirming impaired deficit in sperm maturation and count, viability and motility (

Table 3) following oral exposure to HgCl

2. This finding corroborated earlier studies that indicated ultrastructural impairment of the testis and epididymis concerning mercury chloride exposure (El-Desoky et al., 2013; Kalender et al., 2013). TQ-treated rat cohorts showed protection against testicular ultrastructural damage caused by HgCl

2.

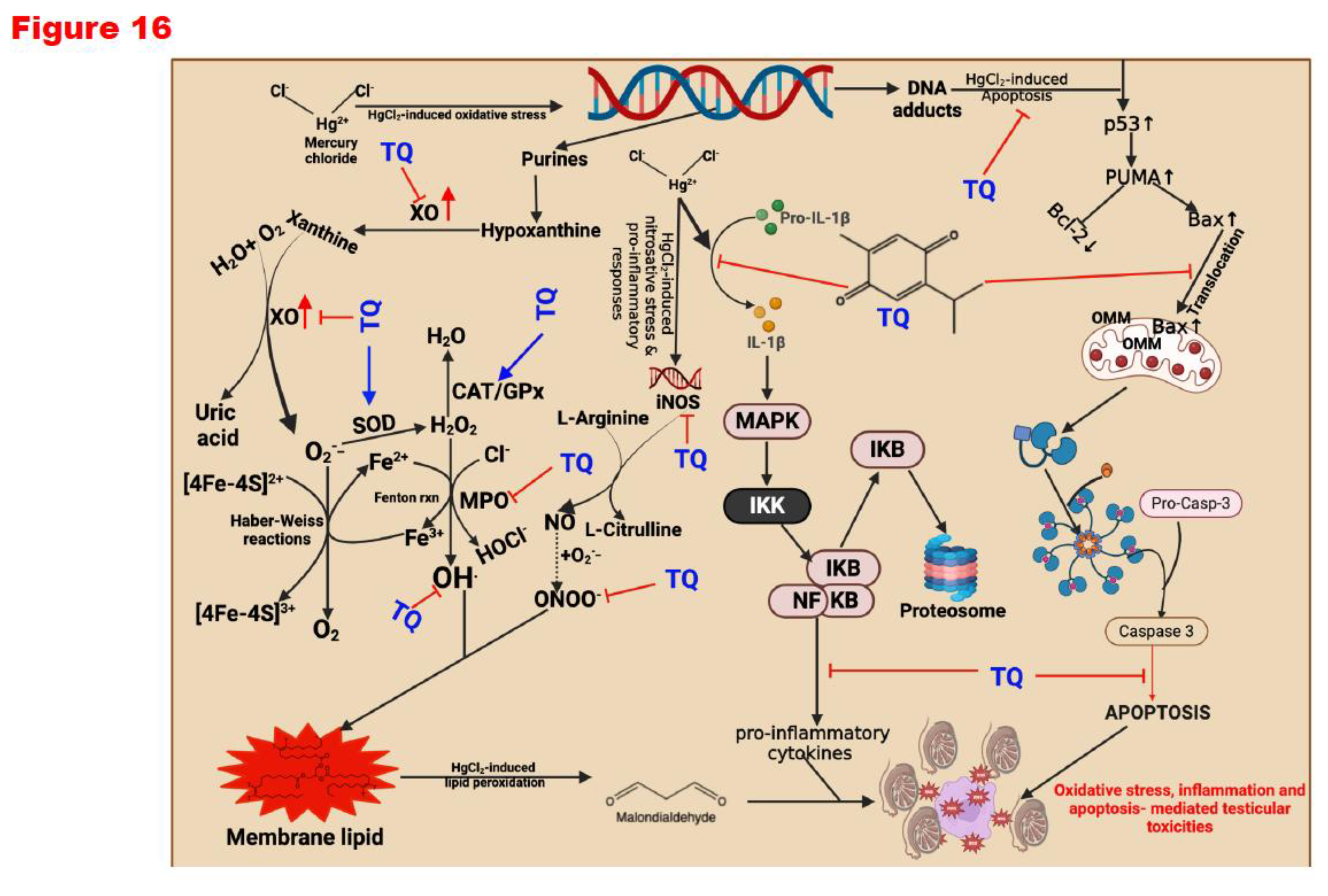

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), specifically PPAR-α, PPAR-γ, and PPAR δ/β, are an excellent therapeutic target. They have been known to induce antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions (Owumi et al., 2024). They promote optimal health by conferring antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses (Billin, 2008; Lee et al., 2017; Okada-Iwabu et al., 2013; Savkur & Miller, 2006). Molecular docking simulations demonstrated that PPAR δ/β positively engage Nrf-2 and modulate NF-kB function, promoting antioxidants and anti-inflammatory responses. Thus, TQ anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects are by agonistic activation of PPAR-α and PPAR δ/β. Our in-silico studies showed that TQ could act as a PPAR-α and PPAR δ/β agonist, thereby increasing their potential to activate Nrf-2 and inhibit NF-kB. The activation of Nrf-2 upregulates the expression of cytoprotective genes, while inhibition of Nf-kB represses the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators (Owumi et al., 2024). Upon confirming our current observations in conjunction with previous studies, we propose that Thymoquinone (TQ) mitigates the reproductive toxicities induced by mercuric chloride (HgCl2) by enhancing the levels of endogenous antioxidants, which can counteract the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation instigated by HgCl2. This mechanism diminishes pro-inflammatory mediators, apoptosis, and the histological aberrations orchestrated by the toxicant to the reproductive system. Specifically, superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyses the conversion of superoxide anion radicals resulting from HgCl2-induced oxidative DNA damage—arising from the excessive release of purines, hypoxanthine, and xanthine—into hydrogen peroxide. In the absence of transformation into water by catalase (CAT) or glutathione peroxidase (GPx), the resultant hydrogen peroxide has the potential to react with labile iron species (Fe2+/Fe3+) in the Fenton reaction, generating hydroxyl radicals, which represent a more toxic form of ROS. These hydroxyl radicals may interact with membrane lipids, culminating in lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by elevated malondialdehyde levels (MDA or LPO).

Furthermore, should hydrogen peroxide accumulate without effective scavenging, it may react with tissue chlorides in the presence of myeloperoxidase (MPO) to produce hypochlorous acid—another ROS that incites pro-inflammatory responses within tissues. In addition to alleviating oxidative stress, TQ displays an anti-inflammatory effect against HgCl

2 by curtailing the levels of nitric oxide (NO) that HgCl

2 prompts via increased activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase, which elevates tissue NO concentrations. Moreover, TQ demonstrates anti-apoptotic characteristics within the reproductive system by modulating the levels of p53, Bax (a pro-apoptotic protein) and augmenting the activity of Bcl-2 (an anti-apoptotic protein), thereby attenuating the downstream repercussions on caspases-9 and -3. Through these mechanisms, TQ effectively modulates HgCl

2-induced reproductive toxicities in male Wistar albino rats (

Figure 16).

This study has some limitations. We did not measure daily food intake, which limits our understanding of how thymoquinone (TQ) mitigates the effects of mercuric chloride on body weight gain and organ weight. Additionally, the bioavailability of TQ was not assessed, as it was beyond the scope of this study, leaving uncertainty about its systemic absorption and distribution. While molecular docking simulations were employed to identify potential therapeutic targets underlying TQ's antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, these findings are preliminary and require further experimental validation.

Figure 2.

The effect of Thymoquinone on reproductive hormones in rats treated with mercuric chloride for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone, and LH: luteinising hormone.

Figure 2.

The effect of Thymoquinone on reproductive hormones in rats treated with mercuric chloride for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone, and LH: luteinising hormone.

Figure 3.

The effect of Thymoquinone on testicular enzyme activities in rats treated with mercuric chloride for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; ACP: Acid phosphatase; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Figure 3.

The effect of Thymoquinone on testicular enzyme activities in rats treated with mercuric chloride for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; ACP: Acid phosphatase; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Figure 4.

The impact of Thymoquinone (TQ) on catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase activities in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8).

Figure 4.

The impact of Thymoquinone (TQ) on catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase activities in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8).

Figure 5.

The outcome of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) activities in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of experimental rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 5.

The outcome of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) activities in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of experimental rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 6.

The impact of Thymoquinone (TQ) treatment on the levels of glutathione (GSH) and total sulfhydryl groups (TSH) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats administered with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****).

Figure 6.

The impact of Thymoquinone (TQ) treatment on the levels of glutathione (GSH) and total sulfhydryl groups (TSH) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats administered with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****).

Figure 7.

The effect of Thymoquinone (TQ) on the levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and lipid peroxidation (LPO) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 7.

The effect of Thymoquinone (TQ) on the levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and lipid peroxidation (LPO) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 8.

The effect of Thymoquinone on the activities of xanthine oxidase (XO) and protein carbonyl in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 8.

The effect of Thymoquinone on the activities of xanthine oxidase (XO) and protein carbonyl in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 9.

The result of Thymoquinone (TQ) treatment on biomarkers of inflammation- level of Nitric oxide (NO) and the activities of myeloperoxidase in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 9.

The result of Thymoquinone (TQ) treatment on biomarkers of inflammation- level of Nitric oxide (NO) and the activities of myeloperoxidase in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 10.

The influence of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on biomarkers of inflammation- level of Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and Tumour Necrotic Factor alpha (TNF-α) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 consecutive days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 10.

The influence of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on biomarkers of inflammation- level of Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and Tumour Necrotic Factor alpha (TNF-α) in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 consecutive days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 11.

The influence of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on the levels of apoptotic markers- Bax and Bcl-2 in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 11.

The influence of Thymoquinone (TQ) administration on the levels of apoptotic markers- Bax and Bcl-2 in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of male Wistar rats treated with mercuric chloride for a period of 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 12.

The effect of Thymoquinone (TQ) on the level of Protein 53 (P53), a marker of DNA damage in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 12.

The effect of Thymoquinone (TQ) on the level of Protein 53 (P53), a marker of DNA damage in the testes, epididymis and hypothalamus of mercuric chloride-treated male Wistar rats for 28 days. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=8), p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 (*, **, ***, ****). .

Figure 13.

Histological representation of the effect of thymoquinone on testicular damage caused by mercury chloride. The controls and TQ-treated groups show typical testicular structure with well-organised testicular tubules and germinal epithelium. HgCl2-only exposed rat shows testicular degeneration with vacuolation of the seminiferous tubule and severe loss of germinal epithelium. Each bar represents mean values with asterisks indicating significant differences at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 versus control and HgCl2 from histomorphometric data. Thymoquinone (TQ), mercury chloride (HgCl2). H & E section of the testis, scale bar=50µm, magnification: x100 (top row) and x400 (bottom row). .

Figure 13.

Histological representation of the effect of thymoquinone on testicular damage caused by mercury chloride. The controls and TQ-treated groups show typical testicular structure with well-organised testicular tubules and germinal epithelium. HgCl2-only exposed rat shows testicular degeneration with vacuolation of the seminiferous tubule and severe loss of germinal epithelium. Each bar represents mean values with asterisks indicating significant differences at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 versus control and HgCl2 from histomorphometric data. Thymoquinone (TQ), mercury chloride (HgCl2). H & E section of the testis, scale bar=50µm, magnification: x100 (top row) and x400 (bottom row). .

Figure 14.

Epididymal section of thymoquinone and mercury chloride. The control and TQ-treated groups show typical testicular structures with well-organised epididymal epithelium and mature stored spermatozoa. HgCl2-only exposed rat shows epididymal degeneration with fewer stored mature spermatozoa. Each bar represents mean values with asterisks indicating significant differences at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 versus control and HgCl2 from histomorphometric data. Thymoquinone (TQ), mercury chloride (HgCl2). H & E section of the testis, scale bar=50µm, magnification: x100 (top row) and x400 (bottom row). .

Figure 14.

Epididymal section of thymoquinone and mercury chloride. The control and TQ-treated groups show typical testicular structures with well-organised epididymal epithelium and mature stored spermatozoa. HgCl2-only exposed rat shows epididymal degeneration with fewer stored mature spermatozoa. Each bar represents mean values with asterisks indicating significant differences at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 versus control and HgCl2 from histomorphometric data. Thymoquinone (TQ), mercury chloride (HgCl2). H & E section of the testis, scale bar=50µm, magnification: x100 (top row) and x400 (bottom row). .

Figure 15.

A: Molecular docking illustration showing the binding of thymoquinone with PPAR-α (PDB: 1I7G) and PPAR- δ/β (PDB: 3D5F) with ΔG values of –5.9 Kcal/mol and –6.2 Kcal/mol. B: TQ can activate PPAR-α or PPAR-δ/β to mediate anti-oxidant effect or resolve inflammation. Specifically, PPAR-α blocks the activation of NF-kB, thereby preventing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, PPAR-δ/β induces an antioxidant effect by activating Nrf-2, which upregulates the expression of antioxidant genes.

Figure 15.

A: Molecular docking illustration showing the binding of thymoquinone with PPAR-α (PDB: 1I7G) and PPAR- δ/β (PDB: 3D5F) with ΔG values of –5.9 Kcal/mol and –6.2 Kcal/mol. B: TQ can activate PPAR-α or PPAR-δ/β to mediate anti-oxidant effect or resolve inflammation. Specifically, PPAR-α blocks the activation of NF-kB, thereby preventing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, PPAR-δ/β induces an antioxidant effect by activating Nrf-2, which upregulates the expression of antioxidant genes.

Figure 16.

Proposed mechanism of action indicating how Thymoquinone (TQ) suppresses mercuric chloride-alteration of male Wistar rats' testes, epididymis and hypothalamus after a 28-day study. Mercuric chloride is obtained by the action of chlorine on mercury or mercury(I)chloride. It can also be produced by the addition of hydrochloric acid to a hot, concentrated solution of mercury(I) compounds such as the nitrate. The activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and the formation of DNA adducts are part of the cellular responses to stress and damage caused by mercury exposure. While activated, NF-kB mediates pro-inflammatory gene transcription, leading to inflammation. DNA adducts upregulate the expression of p53, which upregulates the expression of PUMA. PUMA then activates Bax. Bax then enters the mitochondria and induces MPTP, releasing cytochrome C. Cytochrome C, combined with Apaf1 and procaspase-9, forms the apoptosome, converting procaspase-9 into active Casp-9. Caspase-9 then activates procaspase-3 to active caspase-3, eventually executing programmed cell death. However, the action of thymoquinone inhibits inflammation and the formation of DNA adducts. It promotes the expression of detoxification enzymes, such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferase (GST) and other antioxidant enzymes from the activation of Nrf2. Created with

https://app.biorender.com/ by Uche Arunsi.

Figure 16.

Proposed mechanism of action indicating how Thymoquinone (TQ) suppresses mercuric chloride-alteration of male Wistar rats' testes, epididymis and hypothalamus after a 28-day study. Mercuric chloride is obtained by the action of chlorine on mercury or mercury(I)chloride. It can also be produced by the addition of hydrochloric acid to a hot, concentrated solution of mercury(I) compounds such as the nitrate. The activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and the formation of DNA adducts are part of the cellular responses to stress and damage caused by mercury exposure. While activated, NF-kB mediates pro-inflammatory gene transcription, leading to inflammation. DNA adducts upregulate the expression of p53, which upregulates the expression of PUMA. PUMA then activates Bax. Bax then enters the mitochondria and induces MPTP, releasing cytochrome C. Cytochrome C, combined with Apaf1 and procaspase-9, forms the apoptosome, converting procaspase-9 into active Casp-9. Caspase-9 then activates procaspase-3 to active caspase-3, eventually executing programmed cell death. However, the action of thymoquinone inhibits inflammation and the formation of DNA adducts. It promotes the expression of detoxification enzymes, such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferase (GST) and other antioxidant enzymes from the activation of Nrf2. Created with

https://app.biorender.com/ by Uche Arunsi.

Table 1.

Materials Used for the Study.

Table 1.

Materials Used for the Study.

| Chemical name |

Catalogue No. |

Company |

| 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate |

4091-99-0 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

69-78-3 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Copper sulfate pentahydrate |

7758-99-8 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate trihydrate |

7758-11-4 |

AK Scientific, Union City, USA |

| Epinephrine |

51-43-4 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Folin-Ciocalteu reagent |

125629 |

J.T Baker (Phillisburg, PH, USA) |

| Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) |

9001-40-5 |

Elabscience Biotechnology Company (Wuhan, China) |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) |

7722-84-1 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Hydrochloric acid |

7647-01-0 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Mercury chloride |

|

AK Scientific, Union City, USA |

| O-Dianisidine |

119-90-4 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Potassium Chloride |

7447-40-7 |

AK Scientific, Union City, USA |

| Potassium dihydrogen phosphate |

7778-77-0 |

AK Scientific, Union City, USA |

| Reduced glutathione (GSH) |

70-18-8 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Sodium azide |

26628-22-8 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Sodium hydroxide |

1310-73-2 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Sodium-Potassium tartrate |

6381-59-5 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Sulphosalicylic acid |

5965-83-3 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Trichloroacetic acid |

76-03-9 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) |

504-17-6 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

| Thymoquinone |

490-91-5 |

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. |

| Trichloroacetic acid |

76-03-9 |

Molychem, Mumbai India |

| Xanthine |

69-89-6 |

Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) |

Table 2.

Body weight gain and relative Testis, Epididymis, and Hypothalamus weight of rats following exposure to HgCl2 for 28 days.

Table 2.

Body weight gain and relative Testis, Epididymis, and Hypothalamus weight of rats following exposure to HgCl2 for 28 days.

*Total rats per grouping

|

Control

(8)

|

HgCl2

(8)

|

TQ

(8)

|

HgCl2+ TQ1

(8)

|

HgCl2+ TQ2

(8)

|

| Body weight gain (g) |

60.86 ± 8.07 |

57.00 ± 12.45 |

61.29 ± 14.20 |

65.25 ± 10.26 |

72.63 ± 16.18 |

| Testes weight (g) |

2.50 ± 0.12 |

2.32 ± 0.07 |

2.52 ± 0.13 |

2.63 ± 0.17 |

2.73 ± 0.22 |

| Relative Testes weight (%) |

1.18 ± 0.18 |

1.09 ± 0.08 |

1.14 ± 0.13 |

1.18 ± 0.09 |

1.21 ± 0.10 |

| Epididymis weight (g) |

0.29 ± 0.01 |

0.29 ± 0.01 |

0.35 ± 0.04 |

0.30 ± 0.03 |

0.34 ± 0.05 |

| Relative Epididymis weight (%) |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

0.16 ± 0.02 |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

| Hypothalamus Weight (g) |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

0.07 ± 0.03 |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.08 ± 0.02 |

0.07 ± 0.02 |

| Relative Hypothalamus Weight (%) |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

Table 3.

Sperm analysis and sperm abnormalities of rats following exposure to HgCl2 for 28 days.

Table 3.

Sperm analysis and sperm abnormalities of rats following exposure to HgCl2 for 28 days.

*Total rats per grouping

|

Control

(8)

|

HgCl2

(8)

|

TQ

(8)

|

HgCl2+ TQ1

(8)

|

HgCl2+ TQ2

(8)

|

| Sperm Functional Analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

| Motility |

90.00±4.62 |

75.00±5.34**** |

72.50±4.62 |

67.50±4.62* |

65.00±5.34** |

| Viability |

96.50±1.60 |

96.13±1.55 |

96.50±1.60 |

96.50±1.64 |

94.88±4.25 |

| Sperm Volume |

5.16±0.05 |

5.17±0.04 |

5.17±0.04 |

5.18±0.03 |

5.18±0.05 |

| Epididymal Sperm Count |

132.40±9.89 |

117.00±11.10* |

113.00±8.55 |

101.90±8.25* |

98.50±10.61** |

| Sperm Abnormalities |

|

|

|

|

|

| Abnormality of the Head (%) |

2.08±0.27 |

2.14±0.13 |

2.15±0.30 |

2.23±0.31 |

2.17±0.53 |

| Abnormality of the Mid-piece (%) |

4.21±0.38 |

4.65±0.25 |

4.67±0.35 |

4.86±0.38 |

5.14±0.25 |

| Abnormality of the Tail (%) |

5.23±0.45 |

5.61±0.53 |

5.56±0.56 |

5.88±0.93 |

6.25±0.48 |

| Total Abnormality (%) |

11.52±0.44 |

12.41±0.63 |

12.38±0.63 |

12.98±1.28 |

13.56±1.10 |