Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

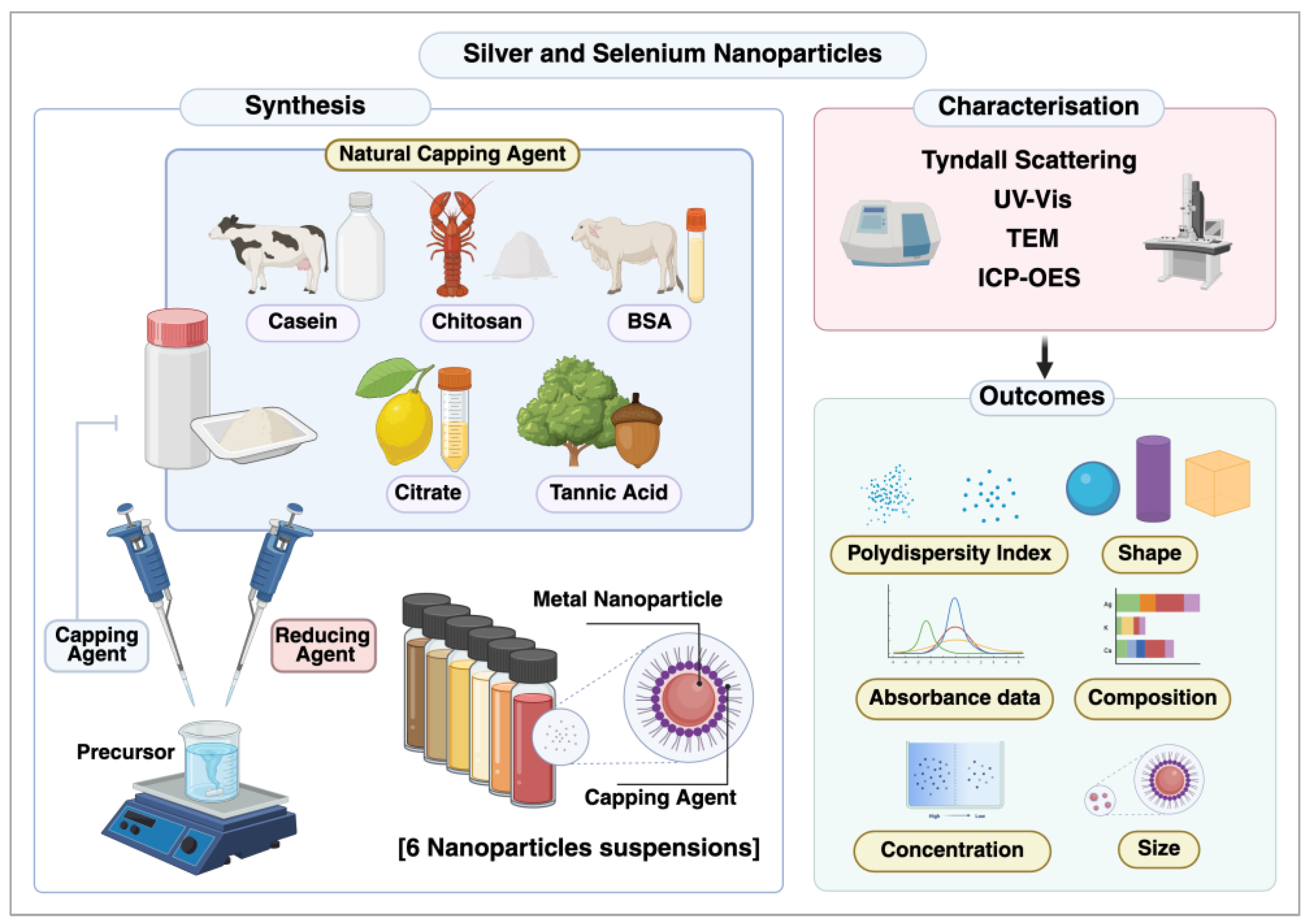

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

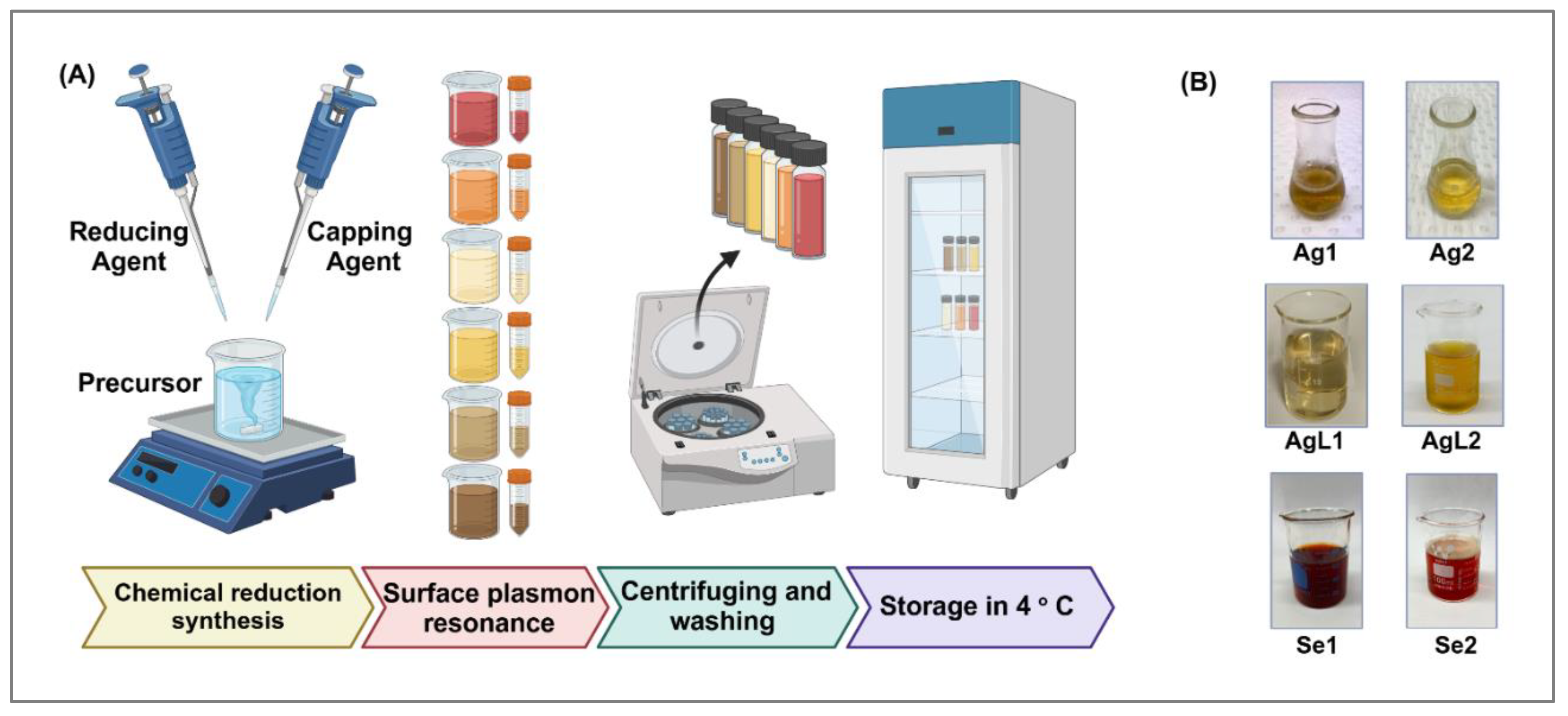

2.1. Preparation of NPs

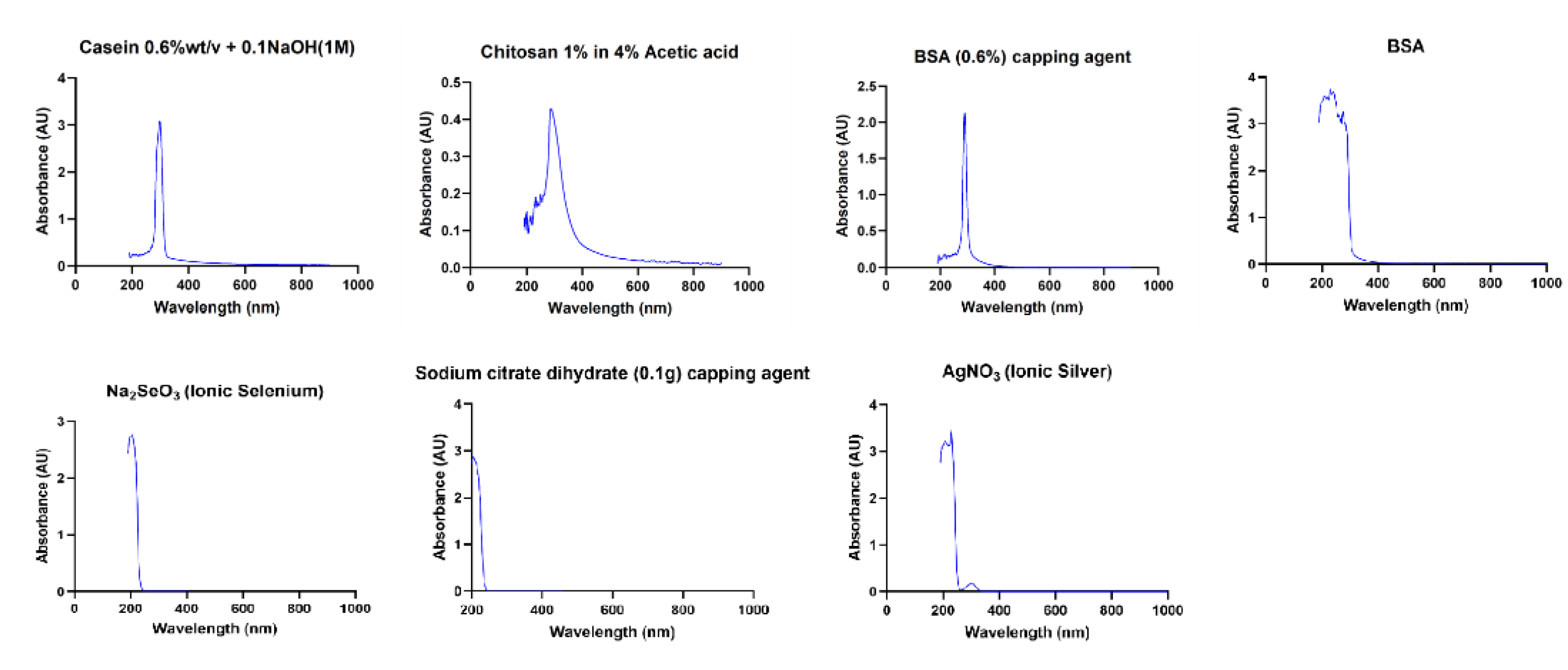

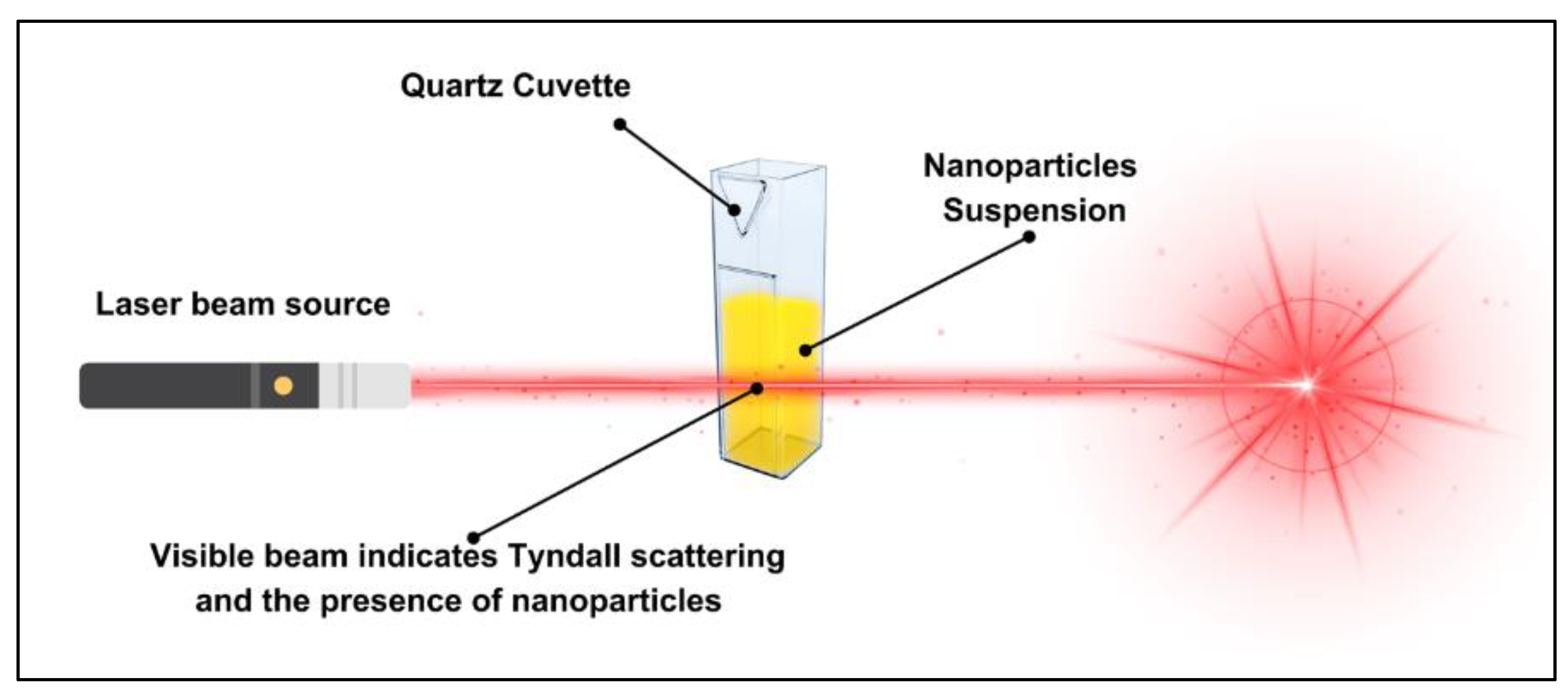

2.2. Characterisation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECC | Early Childhood Caries |

| SF | Silver Fluoride |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| SeNPs | Selenium Nanoparticles |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| DI | Deionised (water) |

| AgNO₃ | Silver Nitrate |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| Na₂SeO₃ | Sodium Selenite |

| NaBH₄ | Sodium Borohydride |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible (Spectroscopy) |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy / Microscope |

| CARF | Central Analytical Research Facility |

| QUT | Queensland University of Technology |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| CRMs | Certified Reference Materials |

| Pb | Lead |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Ag | Silver |

| Se | Selenium |

Appendix A

References

- Nguyen, T. M.; Tonmukayakul, U.; Hall, M.; Calache, H. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Silver Diamine Fluoride to Divert Dental General Anaesthesia Compared to Standard Care. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J. O.; Vaghela, P. M. Silver Diamine Fluoride: A Successful Anticarious Solution with Limits. Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Scott, J. M.; Crystal, Y. O.; Berg, J. H.; Milgrom, P. Silver Diamine Fluoride in Pediatric Dentistry Training Programs: Survey of Graduate Program Directors. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 38, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Nagireddy, V. R.; Reddy, D.; Kondamadugu, S.; Puppala, N.; Mareddy, A.; Chris, A. Nanosilver Fluoride—A Paradigm Shift for Arrest in Dental Caries in Primary Teeth of Schoolchildren: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 12, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafan, A.; Zaazou, M. H.; Sallam, M. K.; Mosallam, O.; El Danaf, H. A. Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy and Nanoparticles Effects on Caries Models. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.; Kopel, J.; Ray, C.; Reed, J.; Reid, T. W. Organo-Selenium Containing Dental Sealant Inhibits Biofilm Formation by Oral Bacteria. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrazia, F. W.; Branco Leitune, V. C.; Garcia, I. M.; Arthur, R. A.; Werner Samuel, S. M.; Collares, F. M. Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on the Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of an Orthodontic Adhesive. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2016, 24, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Du, Z.; Zhu, S.; Geng, H.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Q.; Yang, X. Composite Resin Reinforced with Silver Nanoparticles–Laden Hydroxyapatite Nanowires for Dental Application. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M. A. S.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, K.; Weir, M. D.; Rodrigues, L. K. A.; Xu, H. H. K. Novel Dental Adhesives Containing Nanoparticles of Silver and Amorphous Calcium Phosphate. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, N.; Islam, M. A.; Chowdhury, M. A. Synthesis and Characterization of Plant Extracted Silver Nanoparticles and Advances in Dental Implant Applications. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuqrin, A.; Kaur, I. P.; Walsh, L. J.; Seneviratne, C. J.; Zafar, S. Amelioration Strategies for Silver Diamine Fluoride: Moving from Black to White. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenberg, M.; Misra, S.; Wasik, A. M.; Marzano, C.; Björnstedt, M.; Gandin, V.; Fernandes, A. P. Selenium Induces a Multi-Targeted Cell Death Process in Addition to ROS Formation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Krishnani, K. K.; Singh, N. P. Comparative Study of Selenium and Selenium Nanoparticles with Reference to Acute Toxicity, Biochemical Attributes, and Histopathological Response in Fish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 8914–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y. Study of Nanoparticles Aggregation/Agglomeration in Polymer Particulate Nanocomposites by Mechanical Properties. Compos., Part A 2016, 84, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Nanotechnologies — Antibacterial silver nanoparticles — Specification of characteristics and measurement methods, 2066.

- Khramtsov, P.; Barkina, I.; Kropaneva, M.; Bochkova, M.; Timganova, V.; Nechaev, A.; Byzov, I. Y.; Zamorina, S.; Yermakov, A.; Rayev, M. Magnetic Nanoclusters Coated with Albumin, Casein, and Gelatin: Size Tuning, Relaxivity, Stability, Protein Corona, and Application in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Immunoassay. Nanomaterials 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardean, C.; Davidescu, C. M.; Nemes, N. S.; Negrea, A.; Ciopec, M.; Duteanu, N.; Negrea, P.; Duda-Seiman, D.; Musta, V. Factors Influencing the Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan and Chitosan Modified by Functionalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, S.; Eom, N.; Teh, E. J.; Tamada, K.; Parsons, D.; Craig, V. S. J. The Role of Citric Acid in the Stabilization of Nanoparticles and Colloidal Particles in the Environment: Measurement of Surface Forces between Hafnium Oxide Surfaces in the Presence of Citric Acid. Langmuir 2018, 34, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. Reviewing the Tannic Acid Mediated Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles. J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodake, G.; Lim, S.-R.; Lee, D. S. Casein Hydrolytic Peptides Mediated Green Synthesis of Antibacterial Silver Nanoparticles. Colloids Surf., B 2013, 108, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Meisel, D. Adsorption and Surface-Enhanced Raman of Dyes on Silver and Gold Sols. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 3391–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastús, N. G.; Merkoçi, F.; Piella, J.; Puntes, V. Synthesis of Highly Monodisperse Citrate-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles of up to 200 nm: Kinetic Control and Catalytic Properties. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradi, S.; Shariati, A.; Zargar, N.; Yadegari, Z.; Asnaashari, M.; Amini, S. M.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Antimicrobial Effects of Selenium Nanoparticles in Combination with Photodynamic Therapy against Enterococcus faecalis Biofilm. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V. E.; Vasconcelos Filho, A.; Targino, A. G.; Flores, M. A.; Galembeck, A.; Caldas, A. F.; Rosenblatt, A. A New “Silver-Bullet” to Treat Caries in Children—Nano Silver Fluoride: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K. M.; Hossain, M. M.; Polash, S. A.; Takikawa, M.; Shakil, M. S.; Uddin, M. F.; Alam, M.; Ali Khan Shawan, M. M.; Saha, T.; Takeoka, S.; Hasan, M. A.; Sarker, S. R. Investigation of Antimicrobial Activity and Biocompatibility of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Syzigyum cymosum Extract. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 27216–27229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Germano-Costa, T.; Bilesky-José, N.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Carvalho, L.; Fraceto, L. F.; de Lima, R. Influence of the Capping of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles on Their Toxicity and Mechanism of Action towards Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polywka, A.; Tückmantel, C.; Görrn, P. Light Controlled Assembly of Silver Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmani, A.; Ulm, L.; Kasemets, K.; Kurvet, I.; Erceg, I.; Barbir, R.; Pem, B.; Santini, P.; Marion, I. D.; Vinković, T. Stability and Toxicity of Differently Coated Selenium Nanoparticles under Model Environmental Exposure Settings. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.; Islam, F.; Prinz, C.; Gehrmann, P.; Licha, K.; Roik, J.; Recknagel, S.; Resch-Genger, U. Assessing the Reproducibility and Up-Scaling of the Synthesis of Er,Yb-Doped NaYF4-Based Upconverting Nanoparticles and Control of Size, Morphology, and Optical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwass, D. R.; Lyons, K. M.; Love, R.; Tompkins, G. R.; Meledandri, C. J. Antimicrobial Activity of a Colloidal AgNP Suspension Demonstrated In Vitro against Monoculture Biofilms: Toward a Novel Tooth Disinfectant for Treating Dental Caries. Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Ju, J. E.; Kim, B. I.; Pak, P. J.; Choi, E. K.; Lee, H. S.; Chung, N. Rod-Shaped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Are More Toxic than Sphere-Shaped Nanoparticles to Murine Macrophage Cells. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramenko, N. B.; Demidova, T. B.; Abkhalimov, Е. V.; Ershov, B. G.; Krysanov, E. Y.; Kustov, L. M. Ecotoxicity of Different-Shaped Silver Nanoparticles: Case of Zebrafish Embryos. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 347, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, J.; Gagné, F. Shape-Dependent Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles on Freshwater Cnidarians. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Sai Lung, P.; Zhao, S.; Chu, Z.; Chrzanowski, W.; Li, Q. Shape Dependent Cytotoxicity of PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles on Human Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Lim, B.; Skrabalak, S. E. Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Metal Nanocrystals: Simple Chemistry Meets Complex Physics? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 60–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileikaite, A.; Prosycevas, I.; Puiso, J.; Juraitis, A.; Guobiene, A. Analysis of Silver Nanoparticles Produced by Chemical Reduction of Silver Salt Solution. Medziagotyra 2006, 12, 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.-J.; Kang, J.; Song, C.-Q.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, P.; Song, G.-F. Further Study on Particle Size, Stability, and Complexation of Silver Nanoparticles under the Composite Effect of Bovine Serum Protein and Humic Acid. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2621–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

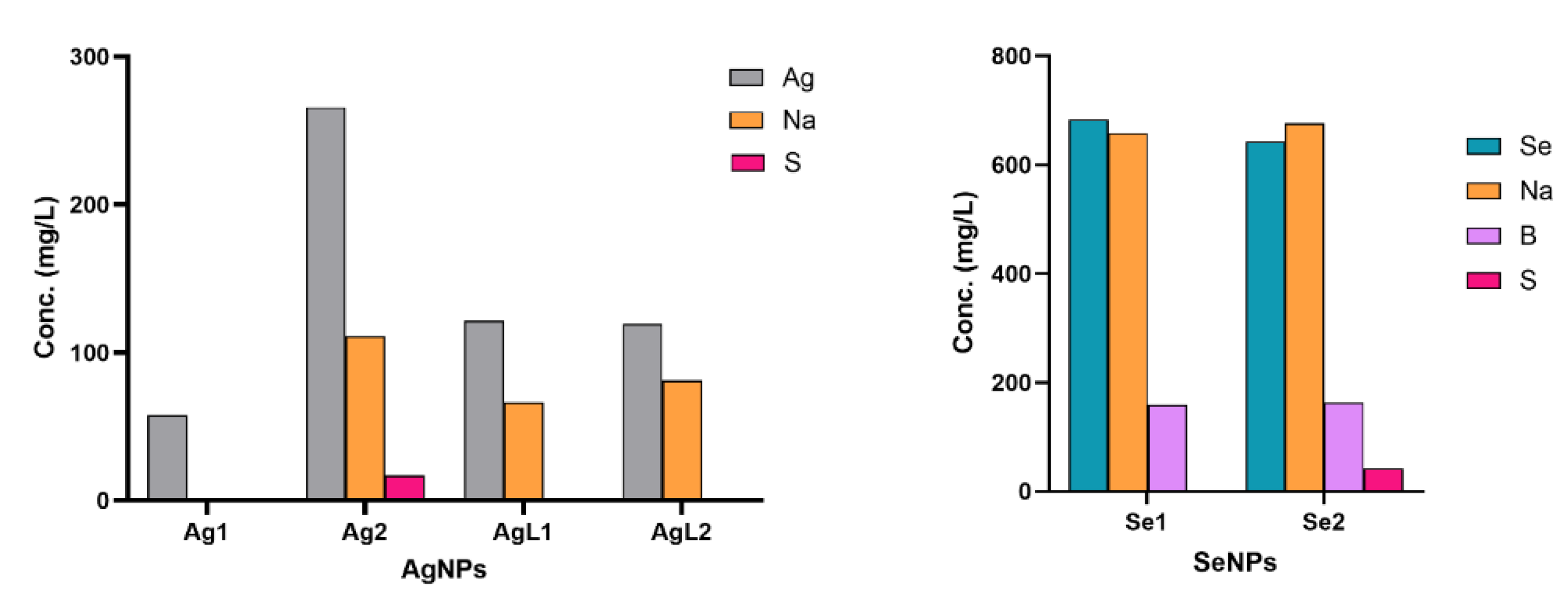

| NPs | Synthesis concentration (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Silver - casein capped (Ag1) | 55.4 |

| 2 | Silver - BSA capped (Ag2) | 265.8 |

| 3 | Silver - citrate capped (AgL1) | 121.6 |

| 4 | Silver - citrate and tannic acid capped (AgL2) | 119.2 |

| 5 | Selenium - chitosan capped (Se1) | 683.1 |

| 6 | Selenium - BSA capped (Se2) | 642.8 |

| Analyte | Ag1 | Ag2 | AgL1 | AgL2 | Se1 | Se2 | Limit of Reporting (mg/L) |

| Conc. (mg/L) | Conc. (mg/L) | Conc. (mg/L) | Conc. (mg/L) | Conc. (mg/L) | Conc. (mg/L) | ||

| Ag | 57.44 | 265.8 | 121.6 | 119.2 | 0.678 | 0.113 | 0.050 |

| Al | <LOR | 0.0761 | 0.0728 | 0.0718 | 0.0707 | 0.069 | 0.050 |

| B | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 159 | 162 | 0.050 |

| Ba | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.010 |

| Be | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.010 |

| Ca | <LOR | 0.0796 | 1.569 | 1.321 | 2.706 | 0.1536 | 0.050 |

| Cd | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Co | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Cr | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.0519 | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Cu | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Fe | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.2791 | <LOR | 0.050 |

| K | 3.913 | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.250 |

| Li | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Mg | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 2.774 | 0.9465 | 0.250 |

| Mn | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Mo | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.250 |

| Na | <LOR | 111 | 66.07 | 81.34 | 658.8 | 675.9 | 0.250 |

| Ni | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| P | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.500 |

| Pb | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.250 |

| S | <LOR | 16.9 | <LOR | <LOR | 0.5252 | 42.16 | 0.500 |

| Se | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 683.1 | 642.8 | 0.250 |

| Si | <LOR | 1.689 | <LOR | <LOR | 0.3339 | <LOR | 0.250 |

| Sr | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.0169 | <LOR | 0.010 |

| Ti | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| V | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Zn | <LOR | 0.9173 | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

| Zr | <LOR | <LOR | AA_01 | <LOR | <LOR | <LOR | 0.050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).