Introduction

Macroalgal ecosystems, an unexplored resource, are strongly marked by the proliferation of macroalgal communities that serve as food, shelter, and protection areas for many marine species. On the peninsula of Cap-Vert (the most extreme triangular point of the West African zone), the months from May to July (warm season) are characterized by a proliferation of macroalgal species in the natural environment and the stranding of the macroalgae species Sargassum spp. on the beach. This growing development of macroalgae species is accompanied by a significant presence of epifaunal species. These epifaunal species live in association with the macroalgae that serve them as food and a place of protection to escape predation. Despite their presence in macroalgae ecosystems, no relationship has been established between macroalgae species and epifaunal species of West African ecosystems. This study conducted on the peninsula of Cap-Vert (Dakar, Senegal) aims to show the relationship that could exist between macroalgae species and epifaunal species.

Studies carried out worldwide on macroalgae ecosystems (Dugan et al., 2003; Hauser et al., 2006; Ingólfsson, 1998; Kirkman & Kendrick, 1997; Olabarria et al., 2007) show the importance of the association of the epifaunal community and that of macroalgae. In New Zealand, (Dufour et al., 2012) and (Inglis, 1989) study the colonizing species of Durvillaea antarctica. In their results, Amphipods remain the most abundant species compared to Staphylinidae, and other Beetle and Dipteran species. These colonizing species represent 99.9% of the total abundance and biomass of the macrofauna of macroalgae ecosystems. In the Netherlands, (Rossi, 2006) shows a high diversity of epifaunal species on the macroalgae Ulva sp. On the Australian coast, (Ince et al., 2007) studies epifaunal species as macrofaunal species that colonize kelps (algal colony that invades beaches); and shows the major importance that kelps play on the growth of epifaunal species. In sum, these studies were based on experiments by burying macroalgae species on the beach to see the epifaunal composition and their reaction to the action of marine waves. For our case, the methodology consists of collecting six species of macroalgae collected in an in situ area (natural state) and to see the colonizing epifaunic community. This approach allows direct contact with macroalgae species to avoid any bias and, thus, see the diversity of epifaunal species and their abundance. The results show a strong presence and abundance of Amphipods on macroalgae species collected in July 2023. On the other hand, for the species of macroalgae collected in May and July 2022, the Copepods are the majority by their abundance and density.

Studying the epifauna associated with macroalgae is crucial for understanding coastal marine ecosystems and their evolution. This study is the first in West Africa to focus on the association between epifauna and macroalgae. In this work, we compare the epifaunal communities associated with different species of macroalgae found on the Cap-Vert Peninsula. The study aims to explore how the composition of the epifaunal community varies according to the species of macroalgae and to examine the specific links that may exist between types of macroalgae and the epifaunal assemblages they host.

Materials and Methods

1. Study Site

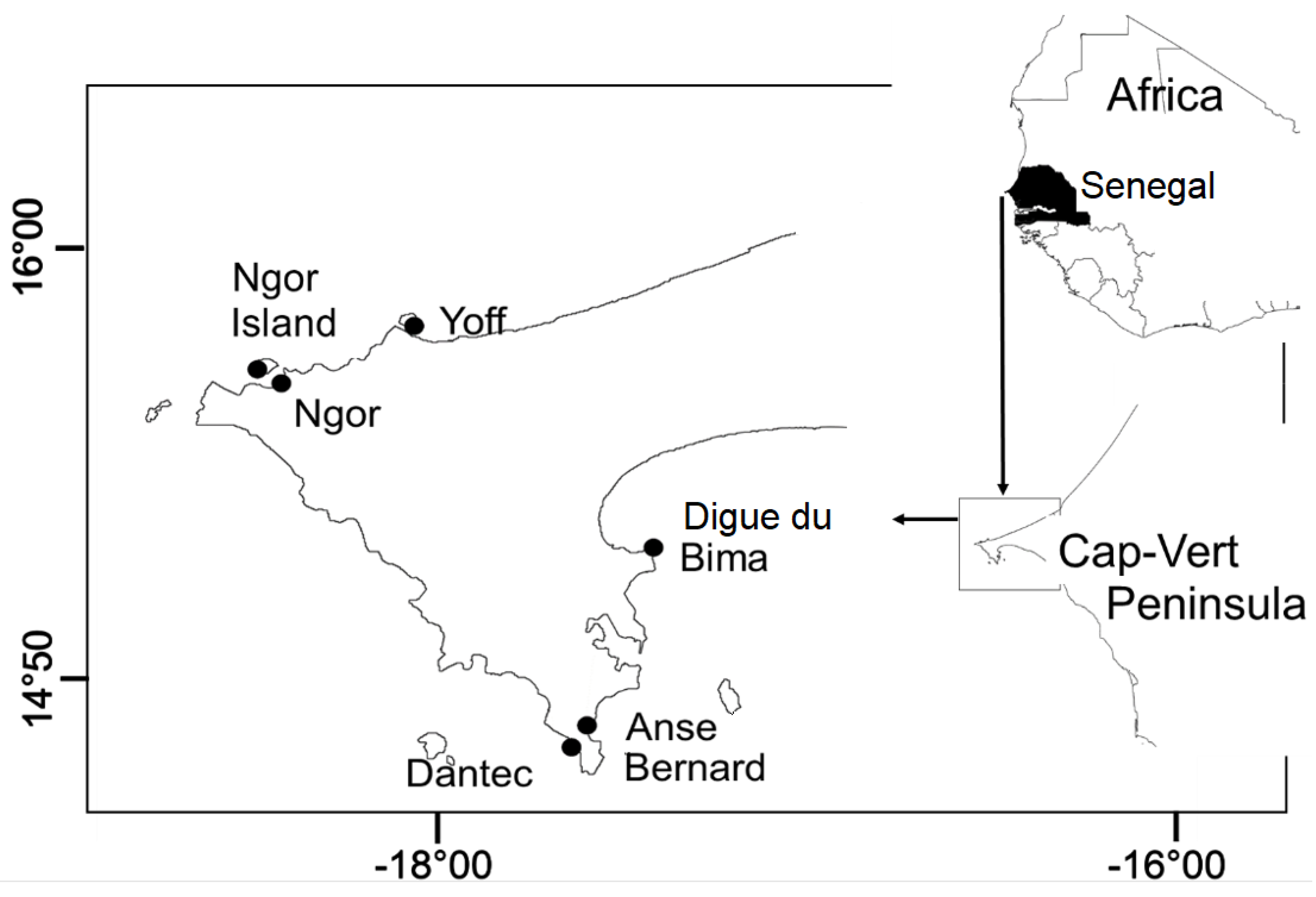

The study was conducted on the Senegalese continental shelf, around the Cap-Vert Peninsula (Senegal), during May–July 2022 and July 2023, corresponding to the warm season (Diankha et al., 2015). The Cap-Vert Peninsula, located at the westernmost point of the West African coast, spans approximately 550 km2 (Sawadogo & Sarr, 2023) and lies between 17°10′–17°30′W and 14°53′–14°35′N. It forms part of the productive Canary Current upwelling system and is subject to both intense ecological productivity and strong anthropogenic pressures (Brehmer et al., 2021).

Sampling was conducted at six sites: Yoff, Ngor Island, Ngor, Bima Digue, Anse Bernard, and Dantec (

Figure 1). These locations were selected to represent a gradient of environmental conditions:

Bima Digue (Bay of Hann) is strongly affected by marine pollution and pollutant accumulation due to restricted current circulation (

Sonko et al., 2023).

Yoff, while relatively less impacted, is under growing pressure from coastal sand extraction and domestic waste associated with Dakar’s urban sprawl (

Diaw, 2018; Sane & Yamagishi, 2004).

Anse Bernard is a socially important recreational beach threatened by demographic pressure and erosion. It is ecologically significant for coastal biodiversity (

Petit & Prudent, 2010).

Dantec suffers from medical waste pollution and erosion but is near the Madeleine Islands National Park, an important marine biodiversity hotspot (

Sonko et al., 2023). This environmental heterogeneity allowed for robust comparison of macroalgal-epifaunal associations across varying levels of exposure, pollution, and substrate types.

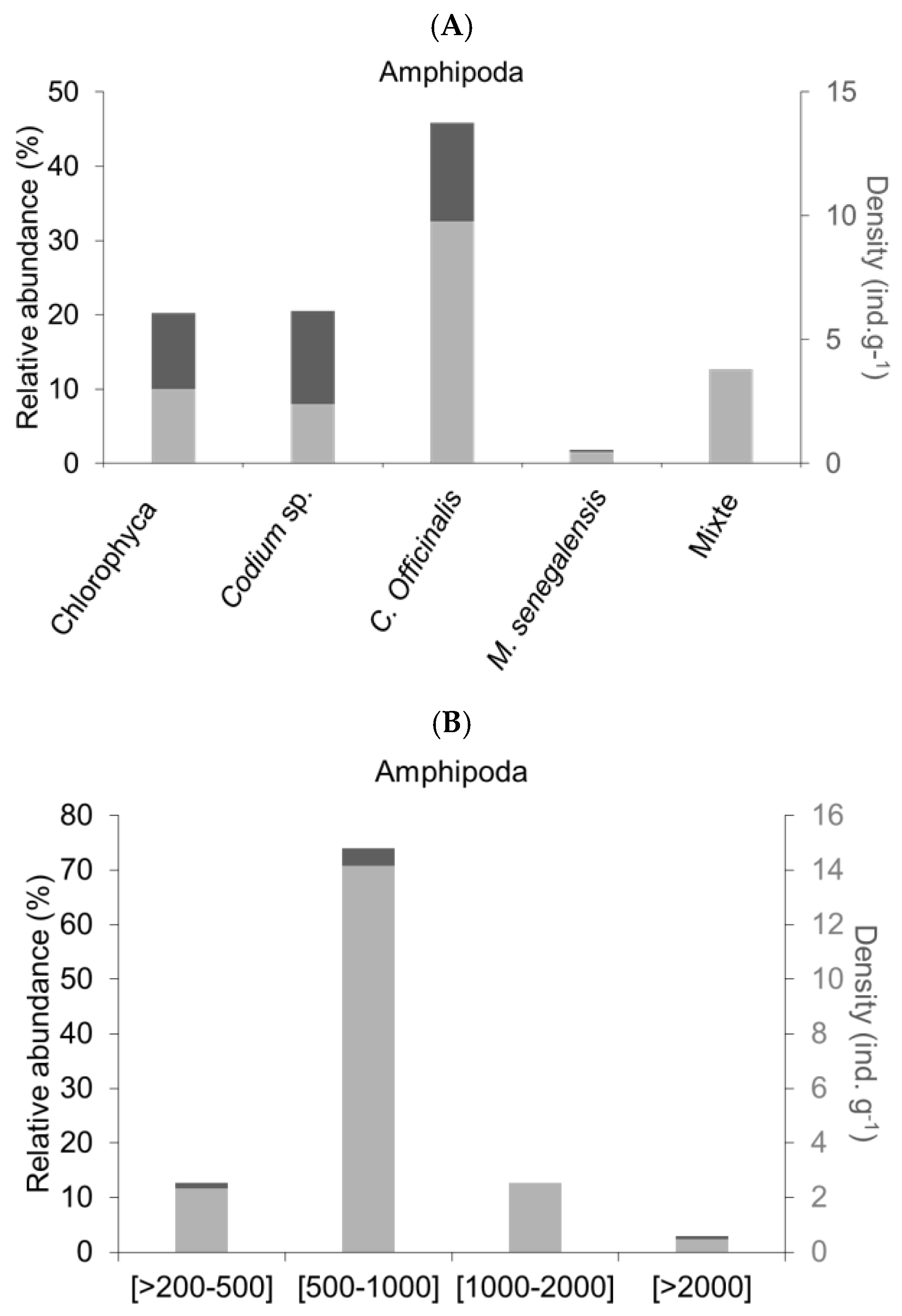

Figure 2.

Relative abundance (in %) of Amphipod individuals in (A) on the classes of macroalgae and in (B) on the size spectra of the epifauna individuals. Mixed is an association between Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae.

Figure 2.

Relative abundance (in %) of Amphipod individuals in (A) on the classes of macroalgae and in (B) on the size spectra of the epifauna individuals. Mixed is an association between Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae.

2. Data Collection

The sampling design aimed to assess how epifaunal assemblages vary according to macroalgal identity, morphology, and site conditions. Macroalgal species were selected based on in situ availability and their relevance across major taxonomic groups (Chlorophyceae, Rhodophyceae, and Phaeophyceae), as well as structural diversity. The sampled taxa included Ulva sp., Codium sp., Corallina officinalis, Meristotheca senegalensis, Sargassum spp., and two additional Chlorophyceae morphotypes (AV and a Chlorophyceae–Rhodophyceae mix). This morphological diversity is known to influence epifaunal colonization and habitat value (Christie et al., 2009; Bates & DeWreede, 2007).

Sampling was conducted in 2022 campaign during opportunistic collection of a stranded holopelagic macroalgae (Sargassum) and Ulva spp. in intertidal zone during low tide, while the 2023 campaign followed a structured protocol focused on benthic species with scuba divers. This hybrid approach captured both permanent and transient macroalgal habitats relevant for epifaunal analysis.

Macroalgal thalli were hand-collected at low tide, rinsed in seawater on-site, and stored in plastic bags in coolers (~5°C). Rinse water from the macroalgae was poured into 400 ml jars with 5% formalin added for preservation. In the laboratory, macroalgae were weighed and identified at family or species level. Epifauna were sorted and identified under a stereomicroscope, following regional identification keys, and subsampled with a Motoda splitter when necessary. A multiparameter probe (Hanna 9829), previously calibrated, was used to measure water temperature, salinity, pH and dissolved oxygen at the surface of each site. pH and dissolved oxygen are not taken into account for this study. Only temperature and salinity are represented.

2.1. Sample Processing

The macroalgae were weighed using a precision balance (± 1g) and identified to the family or species level in the laboratory. The epifauna was separated from the formalin solution under a ventilated hood. The samples were rinsed with distilled water and weighed (precision to the thousandth of a gram).

The epifaunal specimens were identified under a stereomicroscope equipped with a digital camera (Bresser, MikroCam SP 5.0). Identification was carried out using taxonomic keys (Al-Yamani et al., 2010, 2011; Boltovskoy, 1979, 1999; Rose, 1933). Individuals were identified according to the order, genus, or species level. A complete count of the associated epifaunal species was conducted for each macroalgae species. When the numbers were too high, a Motoda box (Motoda, 1959) was used to create aliquot partitions (i.e., 1/2, 1/4, 1/8) according to the formula 1/2n (n: number of partitions). The sample was poured into the Motoda box and then agitated to achieve a homogeneous and equitable volume distribution. Thus, a portion of the volume was poured into a numbered 50 ml tube, representing the aliquot part of the first partition. The operation was repeated up to 1/4096, corresponding to the last partition. The number of individuals found after counting the previous partition was multiplied by 4096 to obtain the total number of individuals in the initial sample (Harris et al., 2000).

The analysis of the size spectra of the epifauna individuals was carried out using four types of sieves (mesh sizes: 2000, 1000, 500, and 200 µm). The epifaunal samples were classified into two categories, each with two classes: the meso < 1000 µm ([200-500] and [500-1000]), and macro, ≥ 1000 µm ([1000-2000] and [>2000]) (Sieburth et al., 1978). For the 2022 samples, two classes were considered [200-500] and [>500].

2.2. Calculation of Epifauna Density

The density of individuals was calculated for each species of macroalgae collected (

Saarinen et al., 2018). The density was calculated only for the macroalgae collected in 2023. This density is given by the number of individuals found on the algae relative to the mass of the collected macroalgae:

N: number of individuals of the epifauna present on the surface of the macroalgae. M: mass of the collected macroalgae; D = density of individuals of the epifauna.

3. Data Analysis

We conducted univariate statistical analyses to explore differences in epifaunal community characteristics across macroalgal species, sites, and other categorical factors. Species density (individuals per gram of algal biomass), Shannon diversity index (H′), and Pielou’s evenness index (J′) were calculated for each sample.

H’: Shannon diversity index. S: total number or cardinality of the species list. P

i: percentage of the abundance of a present species (n

i/N). n

i: number of individuals counted for a present species. N: total number of individuals counted, all species combined.

To compare means between two groups, we used Student’s t-test; for comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was initially tested but replaced by non-parametric equivalents where assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance were violated (Shapiro-Wilk test). Categorical comparisons were assessed using Fisher’s exact test, supplemented by Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 permutations) to ensure robustness with small or uneven sample sizes (Dufour, 2006). Doing so we test the relationship between (i) relative abundance and the mass of the epifauna, (ii) relative abundance and the mass of the algae, (iii) relative abundance and the size of the individuals of the epifauna, (iv) their mass, and the mass of the associated algae, and (v) absolute abundance (number of individuals of a species) of the epifauna and the species of macroalgae.

These methods were chosen to focus on specific hypothesis-driven comparisons involving discrete ecological indicators. Given the modest sample sizes and the targeted scope of our analyses, univariate tests with permutation support provided interpretable and statistically sound results. Multivariate analyses were not employed, as our objective was not to model entire community structure but to test explicit relationships between macroalgal traits and epifaunal descriptors. All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.2), using the tidyverse for data handling (Wickham et al., 2019) and vegan for diversity indices (Oksanen et al., 2012). The Qgis software (version 3.30) was used for map creation.

Results

The Student’s t-test (

Table S1) No significant association was observed between algae types and epifauna species (p=0.64).

The temperature and salinity of the surface water measured show homogeneity across the four stations (

Table S2), with an average salinity of 24.5 ± 0.9 and an average surface water temperature of 28.9°C ± 0.2.

1. Relative Abundance of Epifauna Associated with Macroalgae

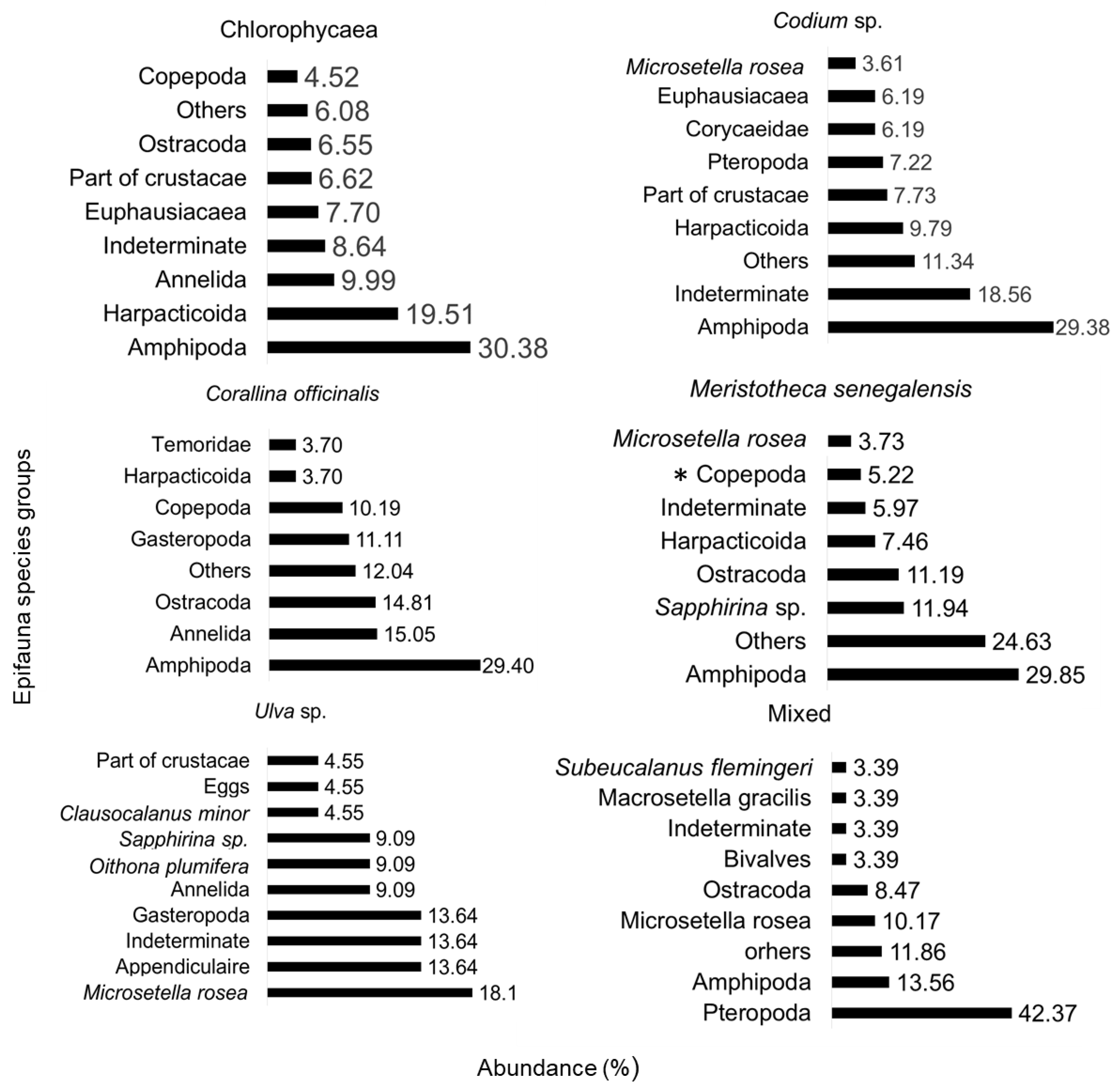

The identification of the epifauna indicates a dominance of Amphipods on the majority of the macroalgae studied in 2023:

C. officinalis,

M. senegalensis,

Codium sp. and the Chlorophyceae AV with respective rates of 29, 30, 29, and 30%, remarkably consistent. For

Ulva sp., the zooplankton species

Microsetella rosea (18%) was dominant, and for the macroalgae referred to as ‘Mixed’, the order of Pteropoda (42%) was predominant. Significant rates (min.: 0.01% and max.: 1.53%) of unidentified individuals were observed across all macroalgae species. Eleven subgroups of epifauna were identified at lower rates: Annelida, Ostracoda, Gasteropoda, Copepoda, Cirripedia, Ctenophora, Cumacea, Decapoda, as well as fish larvae, Bivalves, and Euphausiacea (

Figure 3).

Sapphirina sp. is an identified Copepod, bringing the group of Copepods to a total of 17%.

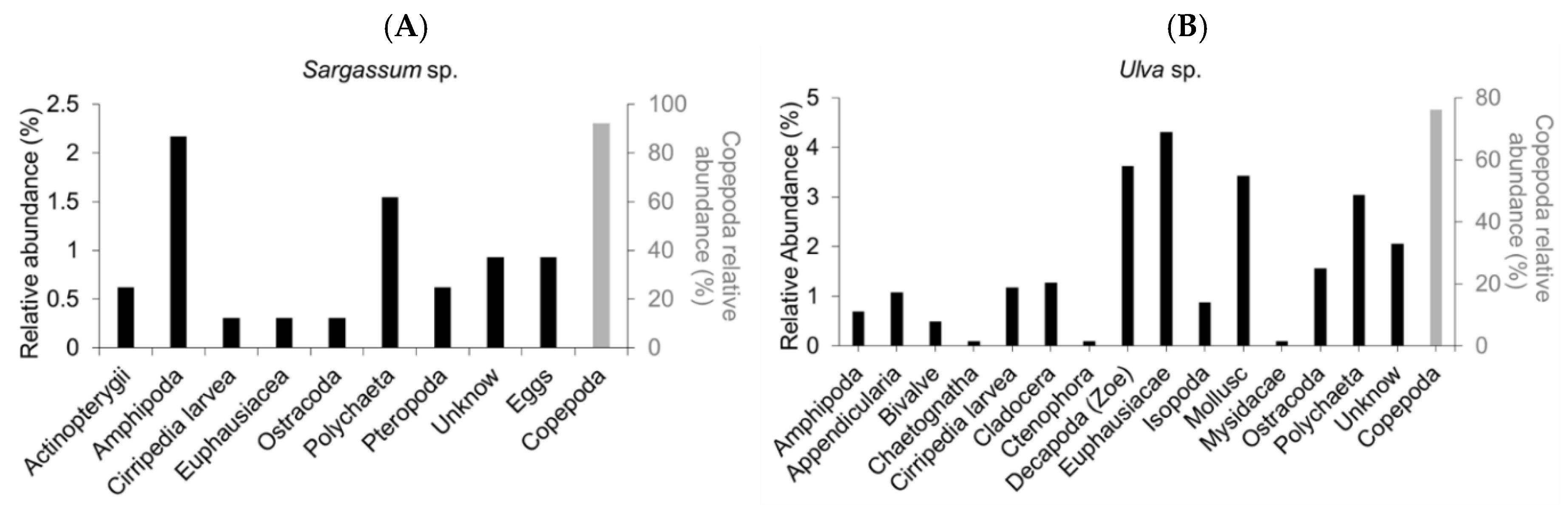

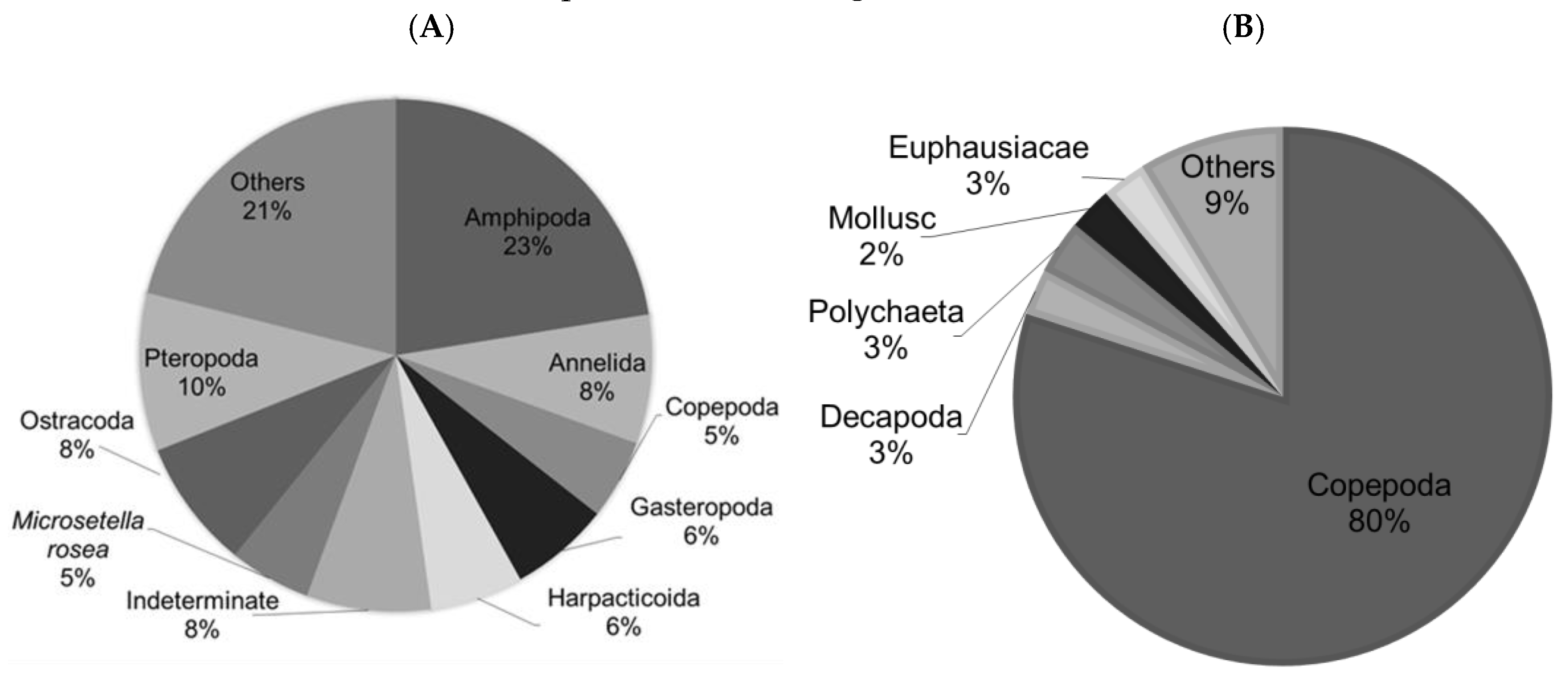

The identification of the composition of the epifauna collected on

Sargassum spp. and on

Ulva spp. in 2022 shows dominance of Copepods at 92 and 76%, respectively (

Figure 4). The presence of Amphipoda, Cirripedia larvae, Euphausiacae, Ostracoda, Polychaeta, Pteropoda, Eggs, and Actinopterygii (the group of fish larvae) was noted but at a very low rate (min.: 0.3% and max.: 2.2%).

2. Relative Abundance of the Epifauna

The study of the abundance (expressed in %, sampling from 2022 and 2023) of the epifauna shows the presence of eight subgroups, two species of Copepod, one indeterminate group, and one group of “other species” (representing all species with an abundance of ≤ 3%). In the 2022 sampling, Copepods remained the most important epifaunal group with 80% of the relative abundance, followed by Euphausiacae, Polychaeta, and Decapoda at 3% each, and Mollusks at 2% (

Figure 5). In 2023, Amphipods had the highest abundance (23%) followed by Pteropods (10%), Ostracodes (8%), Annelids (8%), Gastropods (6%), and Copepods (5%). In the Copepod group, the species

Microsetella rosea had the highest abundance rate (5%), while the abundance of the Harpacticoida family was 6%. The abundance of indeterminate species was 8% (

Figure 5).

3. Density and Abundance of Epifauna Associated with Macroalgae

The density (ind. g

−1) of epifauna individuals associated with macroalgae showed a high density on

Ulva sp. of 100.6 (ind. g

−1), on

C. officinalis of 33.2 (ind. g

−1), and on ‘Mixed’ of 28.2 (ind. g

−1) (

Figure 6). The algal species

Codium sp.,

M. senegalensis, and the Chlorophyceae algae had significantly lower epifaunal densities of 9.2, 2.1, and 9.9 (ind. g

−1), respectively. The highest abundance was noted on

C. officinalis (35%), followed by ‘Mixed’ (19%), then

Codium sp. (16%), Chlorophyceae (15%),

Ulva sp. (14%), and finally

M. senegalensis (1.4%), where the abundance was particularly low.

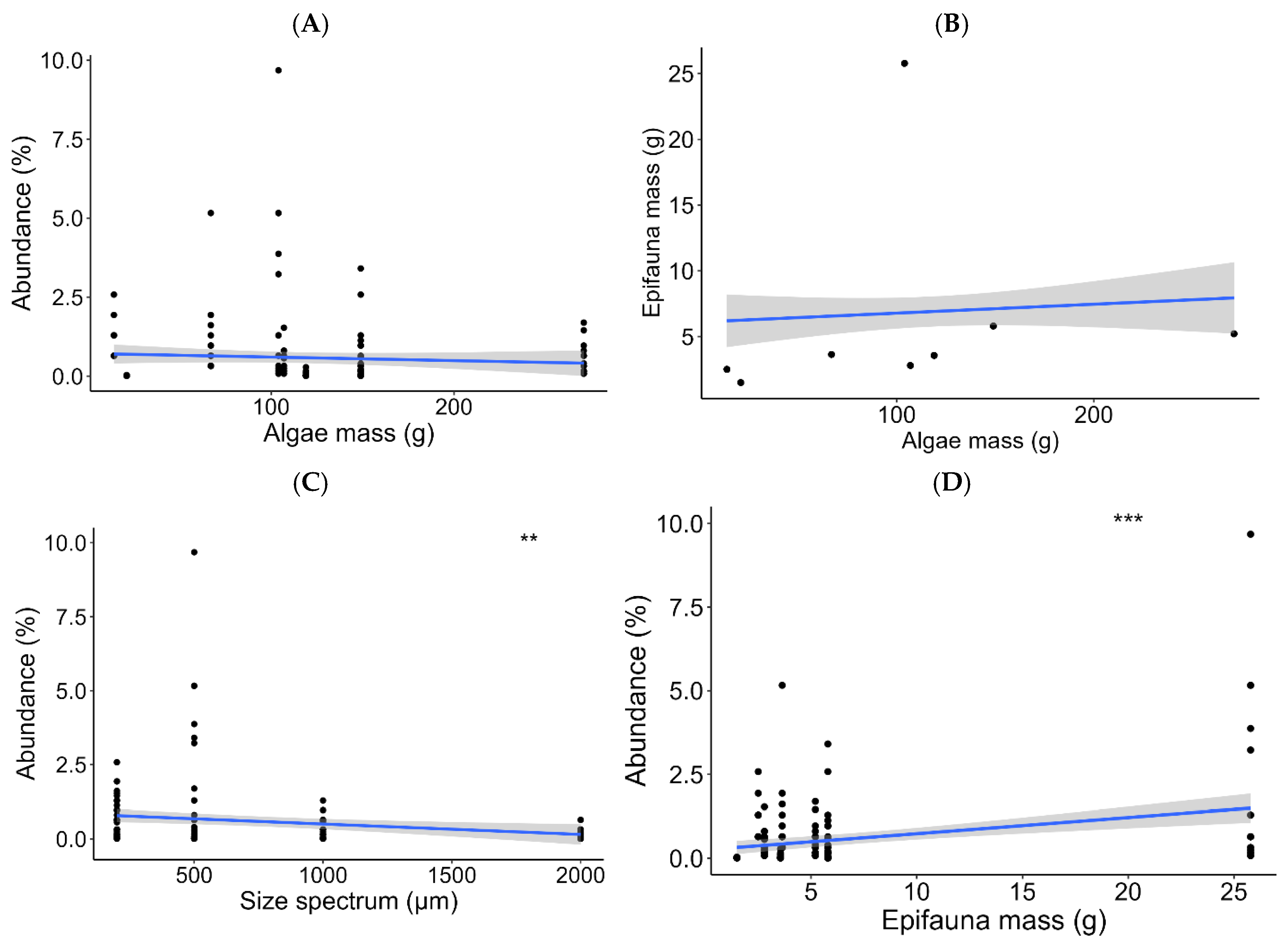

4. Epifauna-Macroalgae Relationship

No significant relationship (

p-value: 0.40) was observed between the mass of the epifauna and that of the associated algae or between the relative abundance of the epifauna and the mass of the associated algae (

p-value: 0.35) (

Figure 7). In contrast, a significant relationship was observed between the absolute abundance of the epifauna and its mass (

p-value: 1.7e-05) and between the absolute abundance of the epifauna and their size (

p-value: 0.0056). A significant relationship was observed (

p-value overall: 4.98e-6) between the absolute abundance of the epifauna and that of the associated macroalgae (

Table S3).

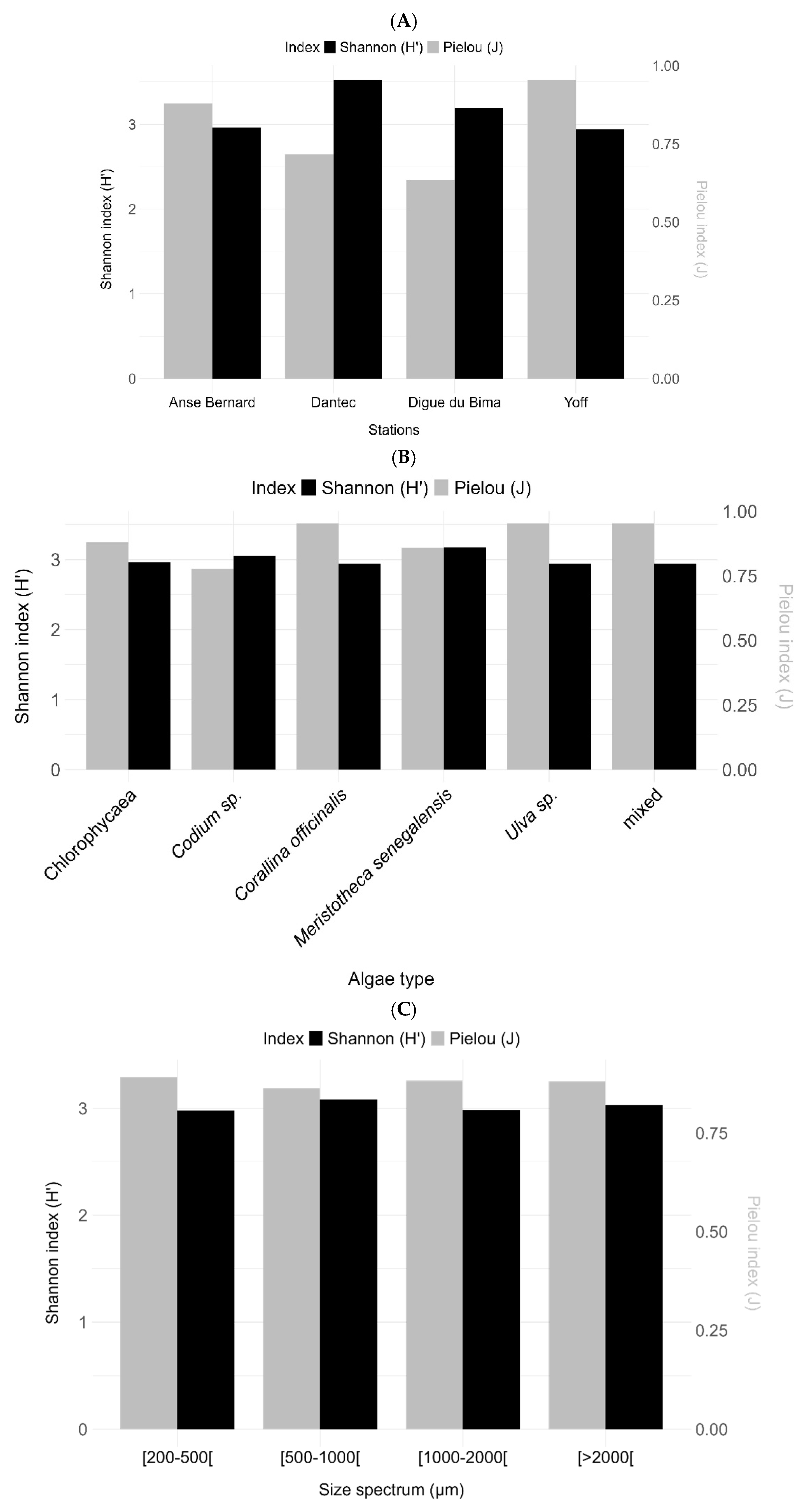

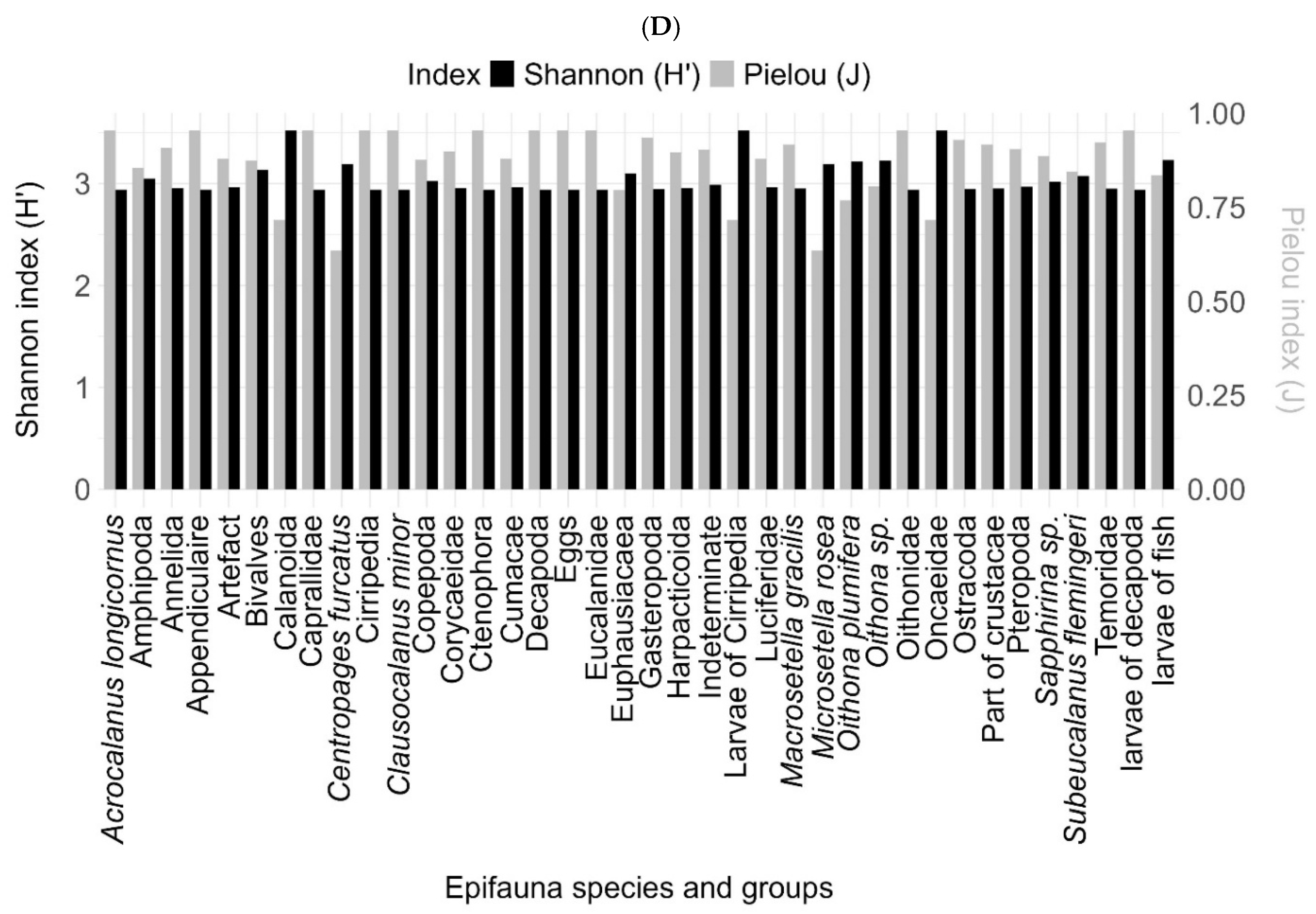

5. Spatial and Phycological Diversity of Epifauna

The Shannon and Piélou indices on the epifauna showed greater diversity at the Bima Digue and Anse Bernard (Shannon 1.4; Piélou 0.3). They were lower at Dantec (Shannon 1.0; Piélou 0.2) and Yoff (Shannon 1.3; Piélou 0.3) (

Figure 8).

The diversities of the epifauna on the algae show a higher diversity on Codium sp. (Shannon 1.5; Piélou 0.4) compared to other macroalgae, e.g., C. officinalis (Shannon 1.4; Piélou 0.3), ‘AV’ (Shannon 1.3; Piélou 0.3), M. senegalensis (Shannon 1.2; Piélou 0.2), ‘Mixte’ (Shannon 1.3; Piélou 0.2), and finally Ulva sp. (Shannon 1.2 and Piélou 0.2).

The highest diversity was observed in the size spectrum [1000-2000] (Shannon 1.6; Piélou 0.4), followed by the spectrum [>2000] (Shannon 1.4; Piélou 0.3), then the spectra [200-500] and [500-1000] with a diversity equal to 1.2 for the Shannon index and 0.2 for the Piélou index. The diversity indices studied on the epifaunal groups showed a greater diversity in the Amphipods, the Euphausiaceae and the indeterminate group with an index rate of 3.5 for the Shannon index and 0.79 for the Piélou index.

Discussion

1. Composition of the Epifauna of Macroalgae

Our results show a high abundance of Amphipods on the macroalgae species collected in July 2023. This significant dominance of Amphipods over macroalgae species is explained by their significant growth during the warm season due to their reproductive activity and their daily migration to escape predation. These observations are consistent with those of (Sutcliffe et al., 1981), who also noted a significant increase in the genus Gammarus spp. at 20 °C for neonatal Amphipods. Similarly, the results of (Dufour et al., 2012) show a high abundance of amphipods on the species of Durvillaea antarctica on the coasts of New Zealand. However, they differ from the results obtained in the Pacific described by (Repelin, 1972). The use of the plankton net type may have underestimated some small-sized species. Moreover, the nature of the rock structure was not constant between the different areas. These results suggest the importance of faunistic monitoring of macroalgae communities in the inventory processes of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and the census of macroalgal biodiversity of the West African zone.

Copepods were the most important epifaunal species in abundance on macroalgae Sargassum spp. and Ulva spp. harvested between May and July 2022. This significant dominance of Copepods over Sargussum spp. and Ulva spp. could be explained by their high presence in ocean waters over 80% of zooplankton. Similarly, the work carried out by (Ndour et al., 2019) on the species of Copepods of the Cap-Vert peninsula shows that all Copepod species dominate the area of the Senegalese continental shelf due to their abundance. In addition, the holopelagic character of Sargassum spp. and Ulva spp. may increase their abundance. Moreover, our results differ from those of (Norton & Benson, 1983), which shows a high abundance of Amphipods on the coasts of the western Atlantic during the massive stranding of Sargassum spp. However, our study is limited by the low quantity of species of Sargussum spp. and Ulva spp. These results suggest that holopelagic macroalgae are colonized by local wildlife. And, regular monitoring would be necessary to confirm these trends.

2. Diversity of the Epifauna of Macroalgae

The Shannon and Piélou indices observed on the Amphipods, the Euphausiaceae and the indeterminate ones indicate a more diverse community, possibly related to the adaptability of these subgroups of epifauna compared to the study area. These results join those of (Norton & Benson, 1983), which show a low diversity of Amphipods on the species Sargussum muticum. However, our study remains reduced by the limited number of sampling campaigns. Seasonal follow-ups would be necessary to confirm these trends. In addition, a high diversity of Amphipods is noted during the night, whereas it is low during the day, as revealed (Repelin, 1972) in the waters of the Pacific. This shows that the sampling period can influence epifaunal species diversity. These results also suggest taking into account the nycthemeral variations when sampling epifaunas species of macroalgae ecosystems.

In macroalgae, Codium sp. and Meristotheca senegalensis species host the greatest diversity of epifaunal species. This high diversity compared to other species of macroalgae could be explained by the structural nature of the species Codium sp. and of Meristotheca senegalensis and their high biomass during the hot season on the Senegalese coasts. These results are in agreement with the work of (Jones & Thornber, 2010), who worked on different species of macroalgae from New England and show that the diversity of epifaunal species is more important on the species Codium frageli throughout the year. Similarly, the work of (Gueye et al., 2021) shows that the species Meristotheca senegalensis has a high biomass compared to other macroalgae species from the Senegalese coast during the hot season. Thus, it gathers a significant amount of epifaunal diversity during this sampling period. Similarly, the work of (Drouin et al., 2011) also shows that Codium sp. has the highest diversity of epifaunal species. Nevertheless, the work of (Davenport et al., 1999) is in disagreement, which shows a high diversity of epifauna species on the macroalgae Corallina sp. These results suggest a variation in epifaunal diversity among macroalgae species. However, additional sampling could be done to consolidate these results. Because the limited amount of our data can influence the expected results.

Conclusions

The main objective of our study was to show the relationship that could exist between epifaunal species and macroalgae species. Our results have shown that there is a dependency relationship between the species of epifaunas and macroalgae. Because macroalgae serve as a place of protection to escape predation, food and development of certain species of epifauna. These results suggest that Amphipod species have the highest abundance. And further confirms that the macroalgae species Codium sp. and Meristotheca senegalensis group the greatest diversity of epifaunal species of the Cap-Vert peninsula. These results provide new information on the macroalgae ecosystem of the CapVert peninsula in the inventory of biodiversity estimation processes. However, some limited should be taken into account, including the amount of sampling of macroalgae species, the period of sampling and regular monitoring of macroalgae ecosystems to refine these conclusions. Further in situ studies should be encouraged to better understand the associations of epifaunal species with macroalgae. The nature of the substrate, the thallus structure, the color and the physico-chemical composition of macroalgae are likely to play a role in the epifaunal composition associated with them. Macroalgae are habitats, places of refuge and food sources for many marine organisms, including fish and cephalopod eggs and larvae, thus promoting their survival and growth. Mass strandings of algae such as Sargassum spp. and Ulva spp., by reducing the availability of these habitats and causing mortality of larvae and eggs, may lead to local reduction in recruitment and alteration of marine community structure. Future research integrating these conclusions could allow a more detailed analysis of the epifauna and macroalgae community association of the Cap-Vert peninsula.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Drafting manuscript: IN. Conception/Design of the research integrating these conclusions could allow a more detailed: IN, PB. Collection of Data: IN, PB, WN, and NCB. Data analysis of the epifauna and macroalgae community association of the Cap-Vert peninsula./interpretation: IN, PB, INdour. Intellectual contribution on text/revisions: IN, MSD, PB, YD, INdour, and WN. Fund acquisition: PB and WN. Coordination: WN and BQ. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Funding Declaration

Financial interests: Author I.N. P.B., W.N., M.S.D. have received research support from GIZ (Germany). Author I.N., P.B., W.N., have received research support from IRD (France). Author I.Ndour, W.N., have received research support from ISRA (Sénégal). Author I.N., Y.D., have received research support from UCAD (Sénégal).

Ethics Declaration

Ethics declaration: not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank for their assistance during the field mission at sea, Fulgence Diedhiou (ISRA/CRODT), Dr. Hanane Aroui (IRD, EAR Imago), Ndeye Coumba Bousso (UCAD/ISRA/IRD), Dr Florian Weinberger (Geomar, Kiel) and Miguette Allegre (IRD, EAR Imago).

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

-

Al-Yamani, F. Y., Khvorov, S. A., & Khvorov, A. S. (2010). Interactive guide of planktonic decapod larvae of Kuwait’s waters. Kuwait Institute for Scientific Researches. Electronic Resource. Registry, 2010/009, 4.

-

Al-Yamani, F. Y., Skryabin, V., Gubanova, A., Khvorov, S., & Prusova, I. (2011). Marine zooplankton practical guide. Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, Kuwait, 399.

-

Ba, A., Chaboud, C., Brehmer, P., & Schmidt, J. O. (2022). Are subsidies still relevant in West African artisanal small pelagic fishery? Insights from long run bioeconomic scenarios. Marine Policy, 146, 105294. [CrossRef]

-

Baldé, B. S., Brehmer, P., & Diaw, P. D. (2022). Length-based assessment of five small pelagic fishes in the Senegalese artisanal fisheries. Plos One, 17(12), e0279768. [CrossRef]

-

Boltovskoy, D. (1979). Zooplankton of the south-western Atlantic. South African Journal of Science, 75(12), 541–544.

-

Boltovskoy, D. (1999). South atlantic zooplankton. Backhuys Publishers, volume 1 & 2, 1705 pp.

-

Brehmer, P., Bâ, A., & Failler, P. (2021). Résilience et réactivité des pêcheurs artisans sénégalais: La crise écologique comme moteur d’innovations. Mondes En Développement, 193(1), 109–127. [CrossRef]

-

Connell, S. D. (2005). Assembly and maintenance of subtidal habitat heterogeneity: Synergistic effects of light penetration and sedimentation. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 289, 53–61. [CrossRef]

-

Diankha, O., Thiaw, M., Sow, B. A., Brochier, T., GAyE, A. T., & Brehmer, P. (2015). Round sardinella (Sardinella aurita) and anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) abundance as related to temperature in the Senegalese waters. Thalassas, 31(2), 9–17.

-

Diogoul, N., Brehmer, P., Demarcq, H., El Ayoubi, S., Thiam, A., Sarre, A., Mouget, A., & Perrot, Y. (2021). On the robustness of an eastern boundary upwelling ecosystem exposed to multiple stressors. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

-

Dufour, C., Probert, PK, & and Savage, C. (2012). Macrofaunal colonisation of stranded Durvillaea antarctica on a southern New Zealand exposed sandy beach. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 46(3), 369–383. [CrossRef]

-

Dufour, J.-M. (2006). Monte Carlo tests with nuisance parameters: A general approach to finite-sample inference and nonstandard asymptotics. Journal of Econometrics, 133(2), 443–477. [CrossRef]

-

Dugan, J. E., Hubbard, D. M., McCrary, M. D., & Pierson, M. O. (2003). The response of macrofauna communities and shorebirds to macrophyte wrack subsidies on exposed sandy beaches of southern California. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 58, 25–40. [CrossRef]

-

Harris, R., Wiebe, P., Lenz, J., Skjoldal, H.-R., & Huntley, M. (2000). ICES zooplankton methodology manual. Elsevier. https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=9-q2owZ2psQC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=zooplankton+methodology+manual&ots=No2VV6yzQB&sig=aC7EE5lOf0mwj1xI2EzbPq7kYy0.

-

Hauser, A., Attrill, M. J., & Cotton, P. A. (2006). Effects of habitat complexity on the diversity and abundance of macrofauna colonising artificial kelp holdfasts. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 325, 93–100. [CrossRef]

-

Ince, R., Hyndes, G. A., Lavery, P. S., & Vanderklift, M. A. (2007). Marine macrophytes directly enhance abundances of sandy beach fauna through provision of food and habitat. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 74(1–2), 77–86. [CrossRef]

-

Inglis, G. (1989). The colonisation and degradation of stranded Macrocystis pyrifera (L.) C. Ag. By the macrofauna of a New Zealand sandy beach. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 125(3), 203–217. [CrossRef]

-

Ingólfsson, A. (1998). Dynamics of macrofaunal communities of floating seaweed clumps off western Iceland: A study of patches on the surface of the sea. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 231(1), 119–137. [CrossRef]

-

Jueterbock, A., Tyberghein, L., Verbruggen, H., Coyer, J. A., Olsen, J. L., & Hoarau, G. (2013). Climate change impact on seaweed meadow distribution in the North Atlantic rocky intertidal. Ecology and Evolution, 3(5), 1356–1373. [CrossRef]

-

Kirkman, H., & Kendrick, G. A. (1997). Ecological significance and commercial harvesting of drifting and beach-cast macro-algae and seagrasses in Australia: A review. Journal of Applied Phycology, 9(4), 311–326. [CrossRef]

-

Motoda, S. (1959). Devices of simple plankton apparatus. Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries Hokkaido University, 7(1–2), 73–94.

-

Nguyen, T. H., Brochier, T., Auger, P., Trinh, V. D., & Brehmer, P. (2018). Competition or cooperation in transboundary fish stocks management: Insight from a dynamical model. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 447, 1–11. [CrossRef]

-

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O’Hara, R. B., Simpson, G. L., Sólymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., & Wagner, H. (Directors). (2012). vegan: Community Ecology Package [Video recording].

-

Olabarria, C., Lastra, M., & Garrido, J. (2007). Succession of macrofauna on macroalgal wrack of an exposed sandy beach: Effects of patch size and site. Marine Environmental Research, 63(1), 19–40. [CrossRef]

-

Puspita, M. (2017). Extraction assistée par enzyme de phlorotannins provenant d’algues brunes du genre Sargassum et les activités biologiques [Phdthesis, Université de Bretagne Sud; Universitas Diponegoro (Semarang)]. https://hal.science/tel-01630154.

-

Rose, M. (1933). Faune de France. Fédération française des sociétés de sciences naturelles, Copépode pélagique(26), 377.

-

Rossi, F. (2006). Small-scale burial of macroalgal detritus in marine sediments: Effects of Ulva spp. on the spatial distribution of macrofauna assemblages. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 332(1), 84–95. [CrossRef]

-

Saarinen, A., Salovius-Laurén, S., & Mattila, J. (2018). Epifaunal community composition in five macroalgal species—What are the consequences if some algal species are lost? Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 207, 402–413. [CrossRef]

-

Salam, A. M. A., Ba, N., Ndour, I., Sane, S., Thiaw, M., Diouf, N., Diouf, J., Diop, D., Gueye, M., & Brehmer, P. (2020). Caractérisation de la flore phytoplanctonique dans l’Aire Marine Protégée (AMP) de Bamboung et de deux sites environnants (Sénégal). International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 14(7), 2452–2462. [CrossRef]

-

Sarre, A., Demarcq, H., Keenlyside, N., Krakstad, J.-O., El Ayoubi, S., Jeyid, A. M., Faye, S., Mbaye, A., Sidibeh, M., & Brehmer, P. (2024). Climate change impacts on small pelagic fish distribution in Northwest Africa: Trends, shifts, and risk for food security. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 12684. [CrossRef]

-

Sawadogo, M., & Sarr, D. (2023). Physical and Mechanical Features of the Quaternary Basanites of the Cap-Vert Peninsula of Dakar (Senegal, West Africa). Geomaterials, 13(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

-

Sieburth, J. M., Smetacek, V., & Lenz, J. (1978). Pelagic ecosystem structure: Heterotrophic compartments of the plankton and their relationship to plankton size fractions 1. Limnology and Oceanography, 23(6), 1256–1263. [CrossRef]

-

Svensson, F. (2015). Effects of warming on the ecology of algal-dominated phytobenthic communities in the Baltic Sea [PhD Thesis, Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University]. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:770962.

-

Tanniou, A. (2014). Etude de la production de biomolécules d’intérêt (phlorotannins, pigments, lipides) d’ algues brunes modèles par des approches combinées de profilage métabolique et d’écophysiologie [Phdthesis, Université de Bretagne occidentale—Brest]. https://theses.hal.science/tel-01928483.

-

Thiaw, M., Gascuel, D., Sadio, O., Ndour, I., Diadhiou, H. D., Kantoussan, J., Faye, S., Thiam, M., Meissa, B., & Brehmer, P. (2021). Efficiency of two contrasted marine protected areas (MPA) in West Africa over a decade of fishing closure. Ocean & Coastal Management, 210, 105655. [CrossRef]

-

Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L., François, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., Hester, J., Kuhn, M., Pedersen, T., Miller, E., Bache, S., Müller, K., Ooms, J., Robinson, D., Seidel, D., Spinu, V., … Yutani, H. (2019). Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Maps of the six sampled sites along the Cap-Vert Peninsula (Dakar, Senegal, West Africa), North Tropical Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 1.

Maps of the six sampled sites along the Cap-Vert Peninsula (Dakar, Senegal, West Africa), North Tropical Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance (in %) in 2023 of the specific composition of epifauna on macroalgae of the Cap-Vert peninsula on (a) an undetermined Chlorophyceae, (b) Codium sp., (c) Corallina officinalis, (d) Meristotheca senegalensis, (e) Ulva sp. and (f) Mixed, i.e., association of Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae. The epifauna was identified at the phylum, order, suborder, or species level. The class “others” represents the sum of species with an abundance of 3% or less.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance (in %) in 2023 of the specific composition of epifauna on macroalgae of the Cap-Vert peninsula on (a) an undetermined Chlorophyceae, (b) Codium sp., (c) Corallina officinalis, (d) Meristotheca senegalensis, (e) Ulva sp. and (f) Mixed, i.e., association of Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae. The epifauna was identified at the phylum, order, suborder, or species level. The class “others” represents the sum of species with an abundance of 3% or less.

Figure 4.

Relative abundance (in %) of the in situ epifaunal composition of two species of macroalgae: (A) Sargassum sp., a holopelagic species, and (B) Ulva sp., benthic, in 2022 at Ngor on the Cap-Vert peninsula (Senegal).

Figure 4.

Relative abundance (in %) of the in situ epifaunal composition of two species of macroalgae: (A) Sargassum sp., a holopelagic species, and (B) Ulva sp., benthic, in 2022 at Ngor on the Cap-Vert peninsula (Senegal).

Figure 5.

Total relative abundance (in %) of the associated epifauna with six species of macroalgae sampled in situ (A) on four sites around the Cap-Vert peninsula in 2023, and (B) of two species (benthic [Ulva sp.] and holopelagic [Sargassum sp.]) on the beach of Ngor and Ngor Island (Cap-Vert peninsula) in 2022.

Figure 5.

Total relative abundance (in %) of the associated epifauna with six species of macroalgae sampled in situ (A) on four sites around the Cap-Vert peninsula in 2023, and (B) of two species (benthic [Ulva sp.] and holopelagic [Sargassum sp.]) on the beach of Ngor and Ngor Island (Cap-Vert peninsula) in 2022.

Figure 6.

Density and abundance of epifaunal species according to the associated species or type of macroalgae. In black, the density (ind. g−1) and the abundance (%) in grey. Mixed: association of Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae.

Figure 6.

Density and abundance of epifaunal species according to the associated species or type of macroalgae. In black, the density (ind. g−1) and the abundance (%) in grey. Mixed: association of Chlorophyceae and Rhodophyceae.

Figure 7.

(A) Relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the mass of their associated macroalgae; (B) the mass of epifauna as a function of the mass of the macroalgae; (C) relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the size spectrum of epifaunal individuals; (D) relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the mass of the epifauna. p-value <0.01: **; <0.001: ***.

Figure 7.

(A) Relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the mass of their associated macroalgae; (B) the mass of epifauna as a function of the mass of the macroalgae; (C) relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the size spectrum of epifaunal individuals; (D) relative abundance of epifaunal species as a function of the mass of the epifauna. p-value <0.01: **; <0.001: ***.

Figure 8.

Mean and standard deviation of the Shannon and Piélou diversity indices (A) by sites, (B) by algae type, (C) by size spectra, and (D) by epifaunal species. In black is the Shannon index, and in grey is the Piélou index.

Figure 8.

Mean and standard deviation of the Shannon and Piélou diversity indices (A) by sites, (B) by algae type, (C) by size spectra, and (D) by epifaunal species. In black is the Shannon index, and in grey is the Piélou index.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).