1. Introduction

Suicide remains a critical global public health concern, responsible for over 700,000 deaths each year, with many more surviving attempts (World Health Organization, 2025). Risk is particularly heightened among individuals facing social isolation and unemployment—conditions increasingly prevalent in aging, economically unstable, and socially fragmented societies (Näher, Rummel-Kluge & Hegeri, 2020; Middleton et al., 2004).

Japan exemplifies this paradox. Despite its economic prosperity and universal healthcare system, the country continues to report suicide rates higher than most other OECD nations. Although national figures have declined since the early 2000s, suicide remains a leading cause of death—especially among working-age men and older adults (MHLW, 2024). Beneath these national averages lie deep regional disparities, most notably in rural, depopulating areas where demographic aging, economic stagnation, and social fragmentation converge (Goto, Kawachi, & Vandoros, 2024).

Akita Prefecture illustrates these structural vulnerabilities. In 2022, its suicide mortality rate stood at 23.7 per 100,000—well above the national average of 16.3 (MHLW, 2024). The region is marked by rapid demographic aging (with over 38% of residents aged 65 or older), sustained youth outmigration, and limited economic diversification (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2024). These conditions contribute to widespread solitary living, poor access to mental health services, and restricted employment opportunities—particularly outside of agriculture and small-scale industry. Vulnerability is especially acute among older adults and non-regular workers, who often lack job stability, social protection, and community support (Inoue et al., 2024; Shimazaki et al., 2024).

The link between suicide and social detachment has deep theoretical roots. Social isolation and unemployment are well-established, independent risk factors for suicide, associated with heightened depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and diminished social connectedness (Luo et al., 2024; Niu et al., 2020). Among working-age adults—particularly men—these factors often intersect, contributing to an erosion of identity, meaning, and social integration (Yong et al., 2021; Glei et al., 2024). In cultural contexts such as Japan, where masculine identity is strongly tied to stable employment and family roles, detachment from either domain can induce profound existential strain.

Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (2005) offers a useful framework here, highlighting “thwarted belongingness” and perceived burdensomeness as central psychological mechanisms driving suicidal desire. These mechanisms are especially salient in cases where social roles are lost or unattainable—whether due to unemployment, social withdrawal, or aging-related disconnection.

Non-regular workers represent a large and vulnerable segment of the Japanese labor force, now comprising over 38% of total employment (OECD, 2024). These roles are frequently insecure, low-paying, and poorly integrated into formal workplace cultures. Middle-aged men in such positions face significantly elevated suicide risk, particularly when employment is involuntary or precarious (Kachi, Otsuka & Kawada, 2014). Hikikomori—individuals who chronically withdraw from work, education, and social life—embody the extreme end of this spectrum, experiencing disproportionately high levels of isolation and suicide risk (Yong & Nomura, 2019). Notably, mere participation in work or school does not guarantee emotional connection; individuals with limited social integration may suffer more distress than those formally excluded (Yong, 2024). This underscores the gap between physical inclusion and perceived belonging.

Empirical evidence further illustrates how social context can moderate these risks. Honjo et al. (2018), analyzing data from over 42,000 older adults in Japan, found that men living alone—or in multigenerational households including both spouse and parent—had significantly higher odds of developing depressive symptoms compared to those living solely with a spouse. Crucially, these risks were mitigated in neighborhoods with strong social cohesion, suggesting that community-level social capital can buffer the psychological harms of isolation.

Despite extensive research on the individual effects of social isolation and unemployment, their combined impact remains underexplored—particularly among structurally vulnerable populations such as unemployed, middle-aged men living alone. This intersection warrants closer examination.

To address this gap, the present study investigates suicide mortality in Akita Prefecture from 2018 to 2022, analyzing variations by sex, age, employment status, and cohabitation. By focusing on a demographically and economically marginalized region, we aim to illuminate how overlapping vulnerabilities interact to elevate suicide risk—and how broader structural forces shape the lived experience of isolation.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Scope

This study utilizes specially tabulated suicide mortality data obtained from the Japan Suicide Countermeasures Promotion Center (JSCP), published annually as the Regional Suicide Profile. These profiles are compiled for every prefecture, designated city, and municipality in Japan, and have been distributed since 2017 under the national directive outlined in the 2017 Cabinet-approved General Principles of Suicide Prevention Policy. The aim of the Regional Suicide Profile is to support municipalities in designing and evaluating localized suicide prevention strategies by providing granular data on suicide cases and regional context.

Although the profiles are not publicly disclosed online, they are made available to all local governments upon request and are compiled using officially verified vital statistics (death certificates), municipal registry information, and other administrative records.

The dataset used in this study covers suicide deaths occurring between 2018 and 2022 (Heisei 30 to Reiwa 4) in Akita Prefecture, one of Japan’s most demographically vulnerable regions. For comparative benchmarking, corresponding national data were used from the same JSCP sources.

Importantly, the JSCP aggregates suicide data by demographic attributes and contextual variables, including:

Sex

Age group

Employment status

Living arrangement (cohabitation status)

History of suicide attempts (in some profiles)

Means of suicide

Stress, mental health status, and household structure (when available from municipal data)

In small population groups, even one additional suicide case can cause a significant fluctuation in the suicide rate. To minimize year-to-year volatility and better identify structural patterns among different segments of the population, we calculated a five-year average suicide mortality rate. This five-year average was computed based on the total number of suicide deaths and the estimated population in each demographic group, using annual statistics from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ Population Estimates.

2.2. Variables and Demographic Stratification

The data were stratified across four variables, yielding a total of 24 demographic subgroups:

Sex: Male, Female

Age Group: 20–39, 40–59, 60 and above

Employment Status: Employed, Unemployed

Cohabitation Status: Living with others, Living alone

Each suicide case was assigned to one of these 24 strata based on the deceased’s official records. Employment status and living arrangement were determined from municipal and welfare registries or, in some cases, inferred from available records at the time of death registration.

2.3. Outcome Measure: Suicide Mortality Risk

The main outcome variable was the suicide mortality risk per 100,000 population for each demographic stratum. This was calculated using the formula:

Population denominators were taken from Akita Prefecture’s own regional data and national-level comparative groups. National risk rates for each demographic stratum were used as benchmarks, allowing for localized risk amplification to be observed in Akita.

2.4. Analytical Approach

The analysis was descriptive and comparative in nature. We did not conduct inferential statistical testing due to the ecological level of the data and the absence of case-level information. However, a focus was placed on identifying relative risk differences across strata and on detecting interaction patterns between unemployment and social isolation.

Special attention was paid to:

Identifying the highest-risk subgroups

Comparing Akita’s suicide rates for each stratum with national equivalents

Observing gendered and age-specific patterns of compounded vulnerability

While the study did not employ multivariate modeling, patterns were interpreted through the lens of causal interaction informed by prior theory and demographic consistency.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

All data used in this study were aggregated, publicly available, and devoid of personally identifiable information. As the analysis did not involve human subjects or intervention, ethical approval was not required under institutional or national guidelines.

2.6. Limitations of Methodology Several limitations of the methods are acknowledged:

The analysis is ecological, and results cannot infer individual-level causality.

Employment status and cohabitation status may be inconsistently recorded or interpreted in registry data, particularly in cases of informal work or shared living arrangements.

The study does not control for mental health diagnoses, previous suicide attempts, or access to care, which are known confounders.

The exclusion of persons under 20 years limits generalizability to youth suicide patterns.

Nonetheless, the strength of this approach lies in its ability to identify structurally embedded patterns of vulnerability at the population level using standardized and reproducible public data.

3. Results

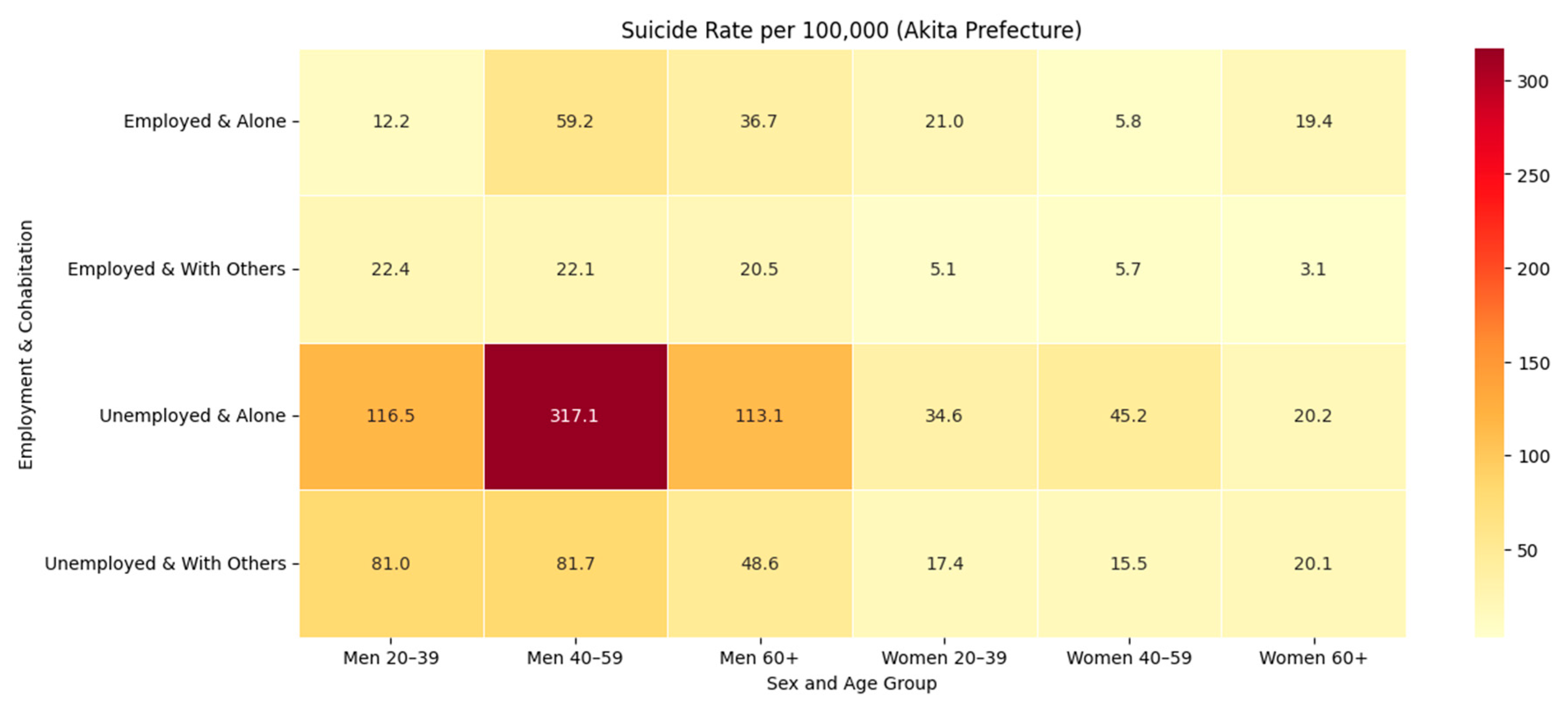

Suicide mortality in Akita Prefecture from 2018 to 2022 revealed sharp disparities across demographic lines, shaped by age, sex, employment status, and cohabitation patterns (

Table 1). Among the 24 strata analyzed, the group facing the highest suicide risk was unemployed men aged 40–59 living alone, with a rate of 317.1 per 100,000—over 14 times higher than their employed, cohabiting counterparts (22.1 per 100,000), who served as the reference group.

Unemployment consistently elevated suicide risk across all categories. Among men aged 20–39, the shift from employment to unemployment increased risk from 22.4 to 81.0 (cohabiting). Among women aged 40–59, the increase was from 5.7 to 15.5. However, the impact of unemployment was notably more severe among men, particularly in midlife, reinforcing known gendered vulnerabilities.

Living alone also independently amplified suicide risk. Employed men aged 40–59 who lived alone had more than double the suicide rate of those who lived with others (59.2 vs 22.1). Among men aged 60 and older, living alone nearly doubled risk as well (36.7 vs 20.5). Among women, however, the pattern was less consistent. For instance, older unemployed women had nearly identical suicide rates regardless of cohabitation status (20.2 vs 20.1), suggesting that living alone may be a stronger risk factor for men than for women.

When unemployment and living alone co-occurred, a multiplicative effect emerged. Among unemployed men aged 60 and older, living alone increased suicide risk from 48.6 to 113.1. Among men aged 20–39, the increase was from 81.0 to 116.5. The most dramatic jump occurred among middle-aged men (40–59), where risk soared from 81.7 to 317.1. Notably, women also experienced compounded vulnerability under conditions of unemployment and isolation. Unemployed women aged 40–59 living alone had a suicide rate of 45.2, compared to 5.7 among employed, cohabiting women of the same age—a nearly eightfold increase. This suggests that while overall suicide rates were lower among women, intersecting disadvantages still produced substantial relative risk.

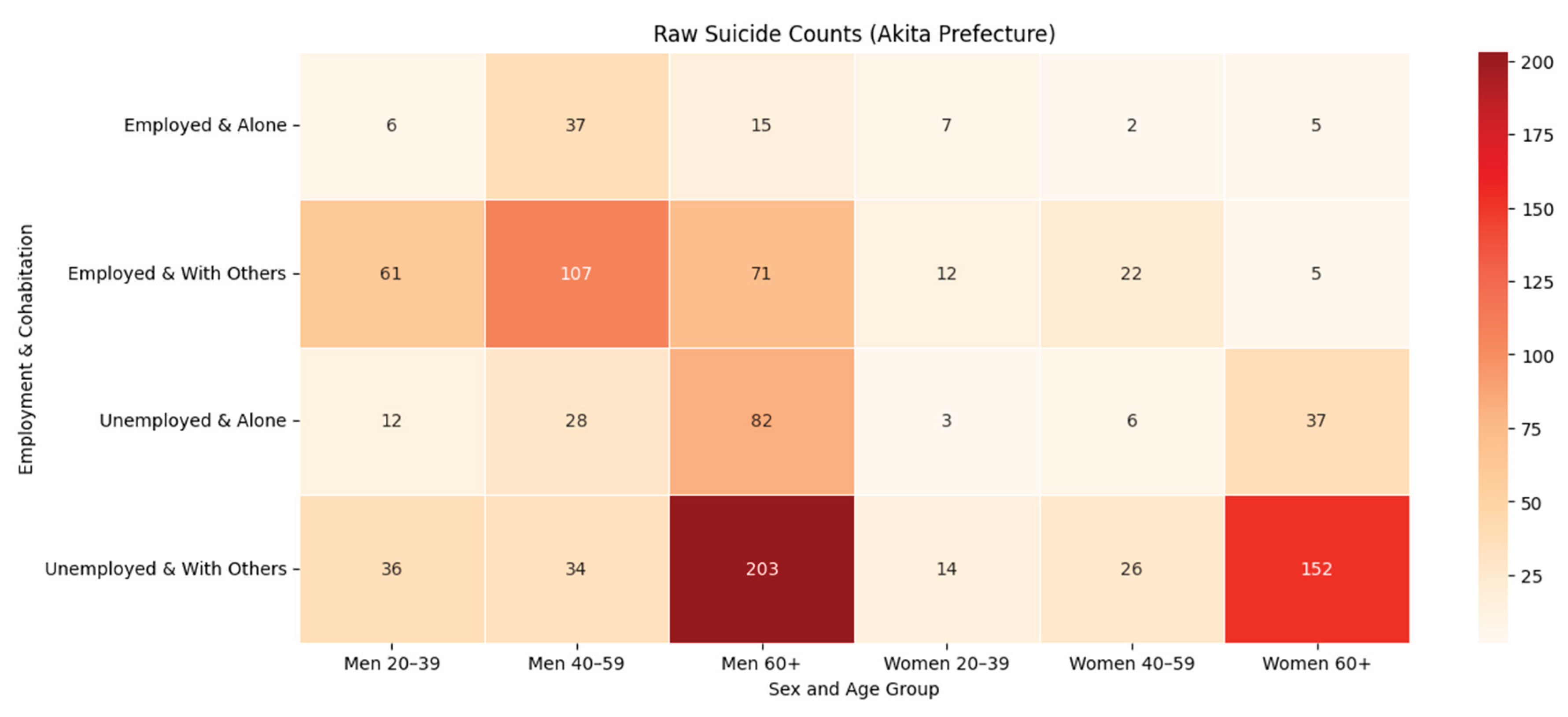

However, examining raw suicide counts paints a different picture. The group with the highest number of suicides was unemployed men aged 60 and older living with others (203 deaths)—more than seven times the number recorded among the highest-risk group. This contrast between

total burden and

per capita risk highlights two distinct policy imperatives: reducing suicide mortality where numbers are greatest, and intervening early in smaller, acutely vulnerable populations (see

Figure 1). In contrast, the highest suicide

rate was observed among unemployed men aged 40–59 living alone, at 317.1 per 100,000—underscoring an acute concentration of risk in a smaller subgroup (see

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

These findings reveal stark social gradients in suicide mortality in Akita, shaped by structural precarity and social isolation. The highest-risk group—unemployed, middle-aged men living alone—faced a suicide rate over 14 times higher than their employed, cohabiting peers, underscoring the compounding nature of economic and social exclusion. Consistent with prior research, unemployment was a powerful independent risk factor, particularly for men, aligning with Japanese sociocultural norms that tightly link male identity to occupational stability and social utility (Yong & Nomura, 2019; Kachi, Otsuka, & Kawada, 2014).

Living alone also independently heightened risk, especially for men. This finding echoes broader evidence that solitary living can signify social detachment, diminished emotional integration, and limited access to informal care networks—particularly in aging rural contexts like Akita (Luo, 2024; Niu, 2020). For women, cohabitation appeared to matter less, possibly reflecting stronger extra-household social ties or differing norms around emotional disclosure and support.

Importantly, these factors did not operate additively, but interactively. The combination of unemployment and solitary living produced suicide rates far beyond either factor alone. For example, suicide risk for unemployed, cohabiting men aged 40–59 was already elevated (81.7), but it quadrupled when combined with living alone (317.1). Similar, though less extreme, patterns were observed in other male cohorts and among middle-aged women.

These patterns align with Durkheim’s typologies of anomic and egoistic suicide, where weakened social integration and disrupted norms elevate suicidality (Durkheim, 1897), and also with Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide—which emphasizes the role of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide (Joiner, 2005). Both theories help explain how structural marginalization and prolonged disconnection from meaningful roles may foster psychological despair, especially among men whose identities are occupationally and socially defined.

The contrast between high-burden and high-risk groups has direct implications for suicide prevention policy. While older, unemployed men living with others contributed the largest share of suicide deaths, they may not be considered acutely at risk due to lower per capita rates. Conversely, middle-aged, unemployed men living alone represented a smaller population, but experienced catastrophically high suicide rates. Policies that focus solely on population-wide mortality may neglect such hyper-vulnerable subgroups, while risk-based approaches that overlook total burden may miss where prevention can yield the greatest absolute impact.

Thus, suicide prevention must pursue a dual strategy: (1) broad structural interventions aimed at reducing overall burden in large, affected populations, and (2) targeted, high-intensity support for smaller groups facing extreme risk. This may include community outreach, tailored mental health services, and employment reintegration for men in midlife who are socially and economically disconnected.

Finally, Akita’s profile—marked by population aging, outmigration, and economic decline—intensifies these dynamics. Regional structural vulnerabilities interact with individual risk factors, compounding isolation and diminishing protective community cohesion. This reinforces the need for context-sensitive policy responses that address not only psychological pathology, but also the demographic and economic foundations of suicide risk.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant careful consideration. First, its ecological design, using aggregate demographic data, limits the ability to draw causal inferences at the individual level. Suicide is a multidimensional behavior shaped by psychological, interpersonal, and contextual factors that cannot be fully captured through administrative categorizations alone. Second, the measures of employment and cohabitation are based on registry data and may not reflect informal or dynamic statuses—such as underemployment, caregiving roles, or temporary shared living arrangements. This is particularly relevant for non-regular workers, older adults, and hikikomori, whose situations may be fluid and underreported.

Third, the analysis does not account for important individual-level confounders—such as prior suicide attempts, psychiatric diagnoses, substance use, or access to mental health care—that are known to influence suicide risk. The absence of these variables limits the ability to isolate the effect of structural and social determinants. Lastly, while Akita provides a critical lens into regional structural vulnerability, the findings may not be generalizable to urban or economically diverse areas of Japan, where the social fabric and labor markets differ substantially.

Nevertheless, the study's focus on intersecting structural risks within a high-suicide context offers valuable insight into population-level patterns of vulnerability that can inform national suicide prevention strategy.

6. Policy and Prevention Implications

The findings underscore the need for multilevel suicide prevention strategies that address both broad population burden and acute per capita risk, especially in structurally marginalized regions like Akita. The sharp contrast between groups with high suicide counts and those with extreme suicide rates reveals the necessity of dual-focus interventions: population-scale mental health infrastructure for high-burden groups, and precision-targeted support for acutely vulnerable subpopulations.

Policies should prioritize:

Focused outreach to unemployed, middle-aged men living alone, who face suicide risks exceeding 300 per 100,000—indicating critical levels of structural and social disconnection.

Expansion of community-based mental health services in rural and depopulating areas, where care is often inaccessible and stigma remains a barrier.

Strengthening local social cohesion, such as neighborhood mutual aid groups, community centers, and intergenerational support, to buffer isolation—especially for solitary older adults.

Employment reintegration programs for non-regular and long-term unemployed workers, including skills retraining, job placement, and workplace social support systems.

Early warning systems leveraging municipal and welfare registries, enabling proactive engagement with recently unemployed, bereaved, or socially withdrawn individuals.

Gender-sensitive interventions that recognize different pathways to suicide across men and women, integrating flexible approaches that account for caregiving roles, informal networks, and non-economic identities.

To be effective, suicide prevention policy must move beyond the clinic and address the social, economic, and demographic structures that concentrate risk. Particularly in aging, economically declining prefectures, suicide cannot be separated from broader processes of disconnection, disenfranchisement, and demographic collapse. A structurally informed suicide prevention framework is therefore essential—one that aligns public health, labor policy, and community development to target both the volume and intensity of suicide risk.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrates how suicide mortality in structurally vulnerable regions like Akita Prefecture is shaped not only by individual factors but by the convergence of economic precarity and social disconnection. The combination of unemployment and living alone produces dramatically elevated suicide risk, particularly among middle-aged men, whose mortality rates exceeded 300 per 100,000—over 14 times higher than their employed, cohabiting counterparts. At the same time, the highest absolute number of suicides was concentrated among older, unemployed men living with others, highlighting that suicide prevention must grapple with both concentrated risk and cumulative burden.

These findings extend theoretical models of suicide—such as Durkheim’s notions of anomic and egoistic suicide and Joiner’s interpersonal theory—by grounding them in Japan’s unique demographic and labor market context. They also underscore the need to distinguish between numerical burden and relative vulnerability in both research and policy. High suicide counts may demand systemic mental health investment, while extreme per capita risk points to neglected subpopulations in urgent need of targeted intervention.

As Japan continues to confront population aging, rural depopulation, and labor market instability, suicide prevention must evolve into a multi-sectoral strategy. This requires not only expanding clinical services, but also restoring social integration, employment stability, and a sense of purpose—especially among those most structurally and socially excluded. Ultimately, efforts to reduce suicide must prioritize not only those who are most visible in the data, but also those who are most acutely at risk of being forgotten.

References

- Durkheim, E. (1897). Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Routledge (Reprint edition).

- Goto, H. Kawachi, I., & Vandoros, S. (2024). The association between economic uncertainty and suicide in Japan by age, sex, employment status, and population density: An observational study. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 46, 100969.

- Honjo, K. Tani, Y., Saito, M., Sasaki, Y., Kondo, K., Kawachi, I., & Kondo, N. (2018). Living alone or with others and depressive symptoms, and effect modification by residential social cohesion among older adults in Japan: The JAGES longitudinal study. Journal of Epidemiology, 28(7), 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y. Nakatani, H., Ono, I., & Peng, X. (2024). Factors related to a sense of economic insecurity among older adults who participate in social activities. PLOS ONE, 19(3), e0301280. [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T. (2005). Why People Die by Suicide. Harvard University Press.

- Kachi Y, Otsuka T, Kawada T. (2014). Precarious employment and the risk of serious psychological distress: a population-based cohort study in Japan. Scand J Work Environ Health, 40(5):465-472. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Wang, J., Chen, X., Cheng, D., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Assessment of the relationship between living alone and suicidal behaviors based on prospective studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, Article 1444820. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, N. Whitley, E., Frankel, S., Dorling, D., Sterne, J., & Gunnell, D. (2004). Suicide risk in small areas in England and Wales, 1991–1993. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(1), 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2024). White paper on suicide prevention 2024–2025. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001464705.pdf.

- Näher, A.-F. Rummel-Kluge, C., & Hegerl, U. (2020). Associations of suicide rates with socioeconomic status and social isolation: Findings from longitudinal register and census data. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, Article 898. [CrossRef]

- Niu, L. Jia, C., Ma, Z., et al. (2020). Loneliness, hopelessness and suicide in later life: A case–control psychological autopsy study in rural China. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e119. [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, T. Yamauchi, T., Takenaka, K., & Suka, M. (2024). The link between involuntary non-regular employment and poor mental health: A cross-sectional study of Japanese workers. International Journal of Psychology, 59(1), 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2024). Current population estimates as of October 1, 2023.

- World Health Organization. (2025, May 23). Suicide worldwide in 2021: Global health estimates. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076015.

- Yong, R. (2019). Hikikomori is most associated with interpersonal relationships, followed by suicide risks: a secondary analysis of a national cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, Article 247.

- Yong, R. (2020). Characteristics of and gender difference factors of hikikomori among the working-age population: A cross-sectional population study in rural Japan. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi, 67(4), 237–246.

- Yong, R. (2024). Reevaluating hikikomori and challenging loneliness assumptions in Japan: a cross-sectional analysis of a nationwide internet sample. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, Article 1323846.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).