Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

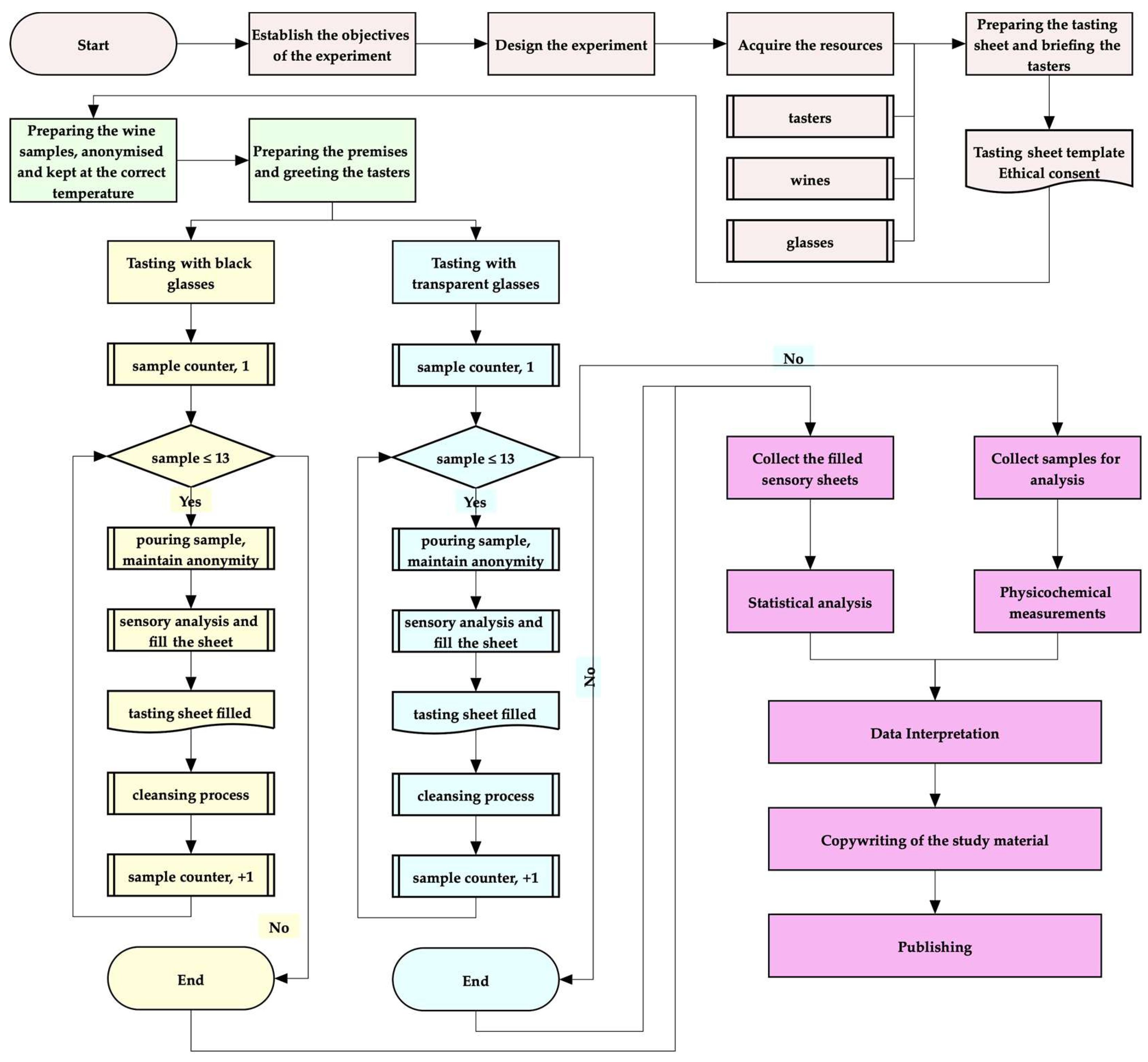

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wine Samples

2.2. Tasters panel

2.3. Design of the experiment

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

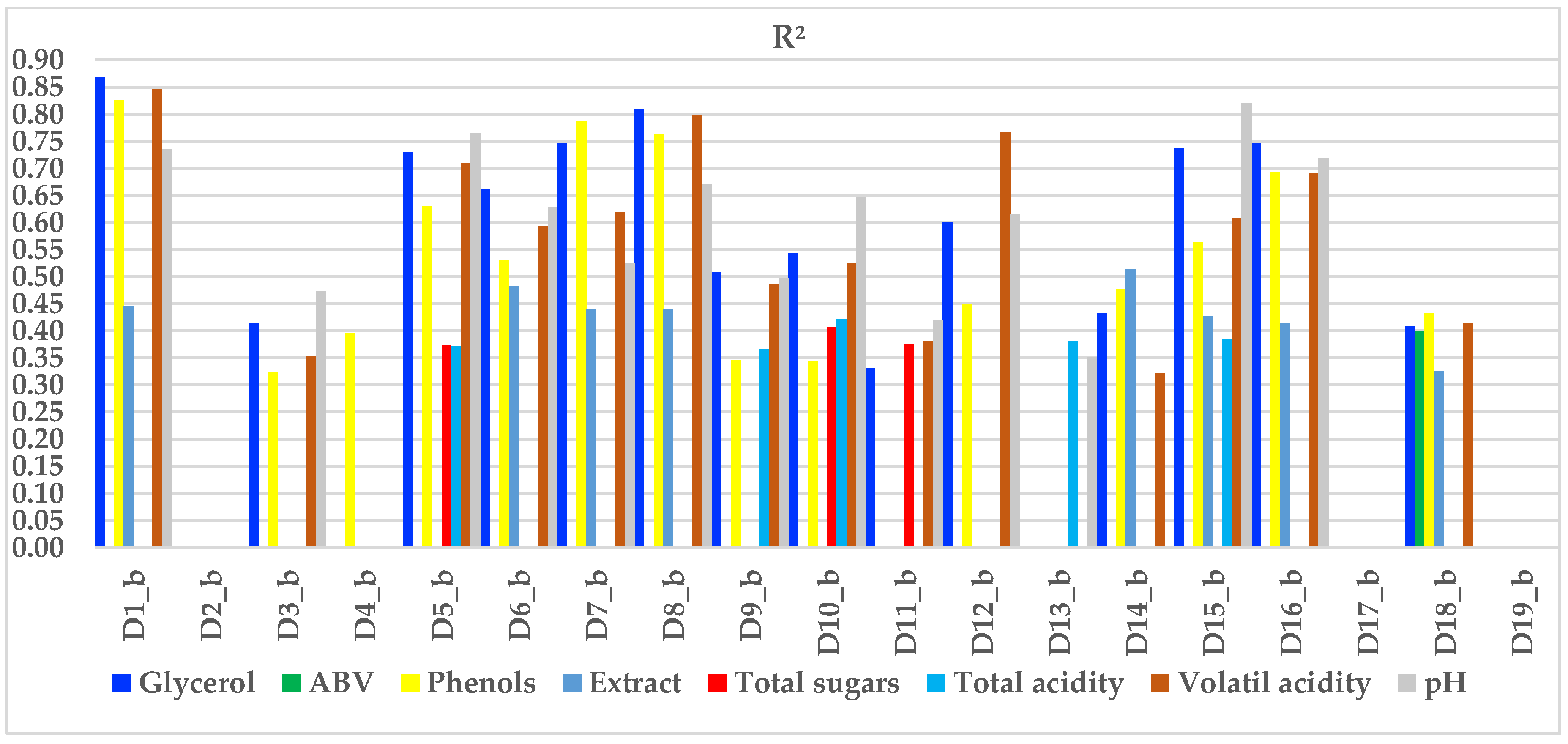

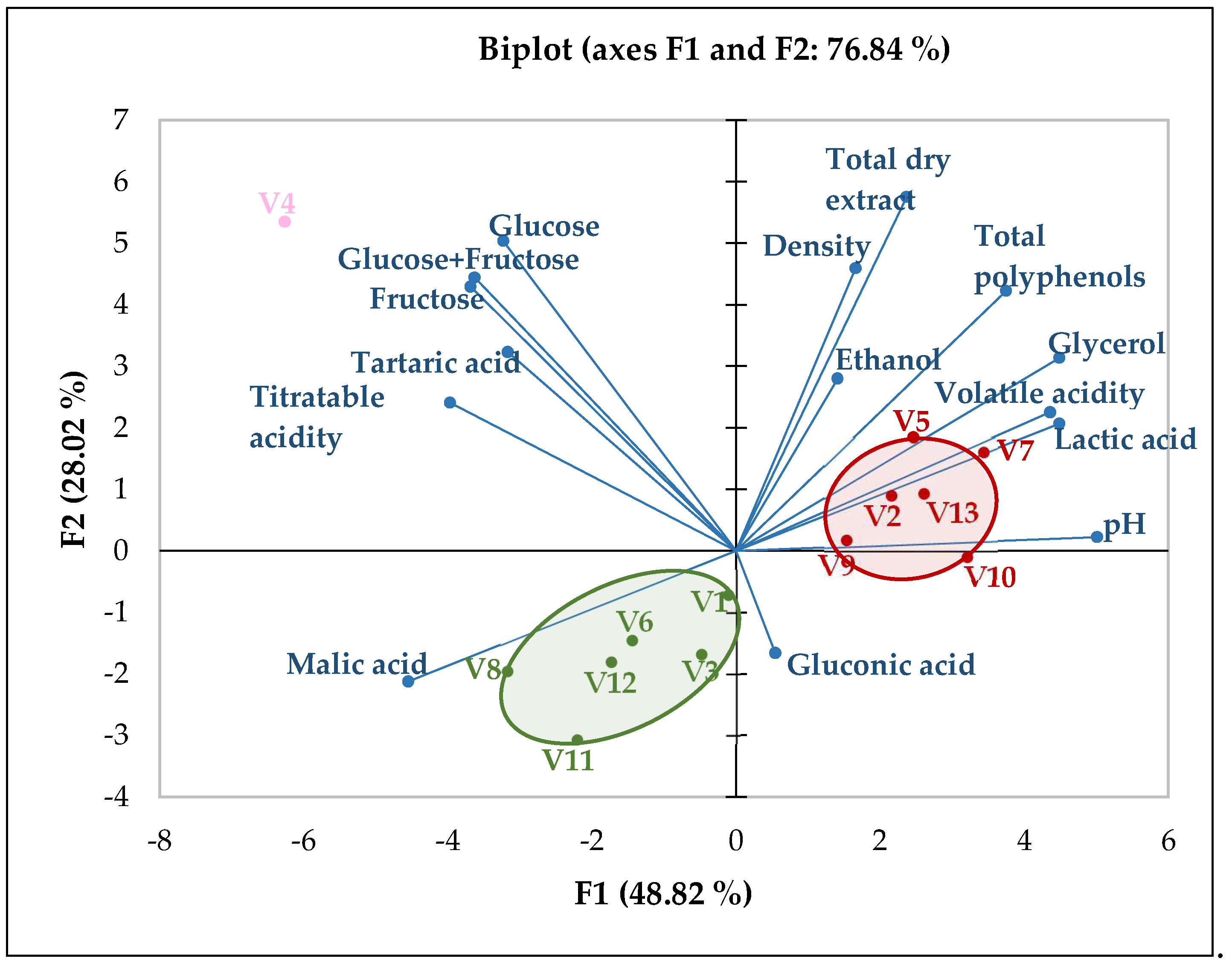

3.1. Physicochemical parameters

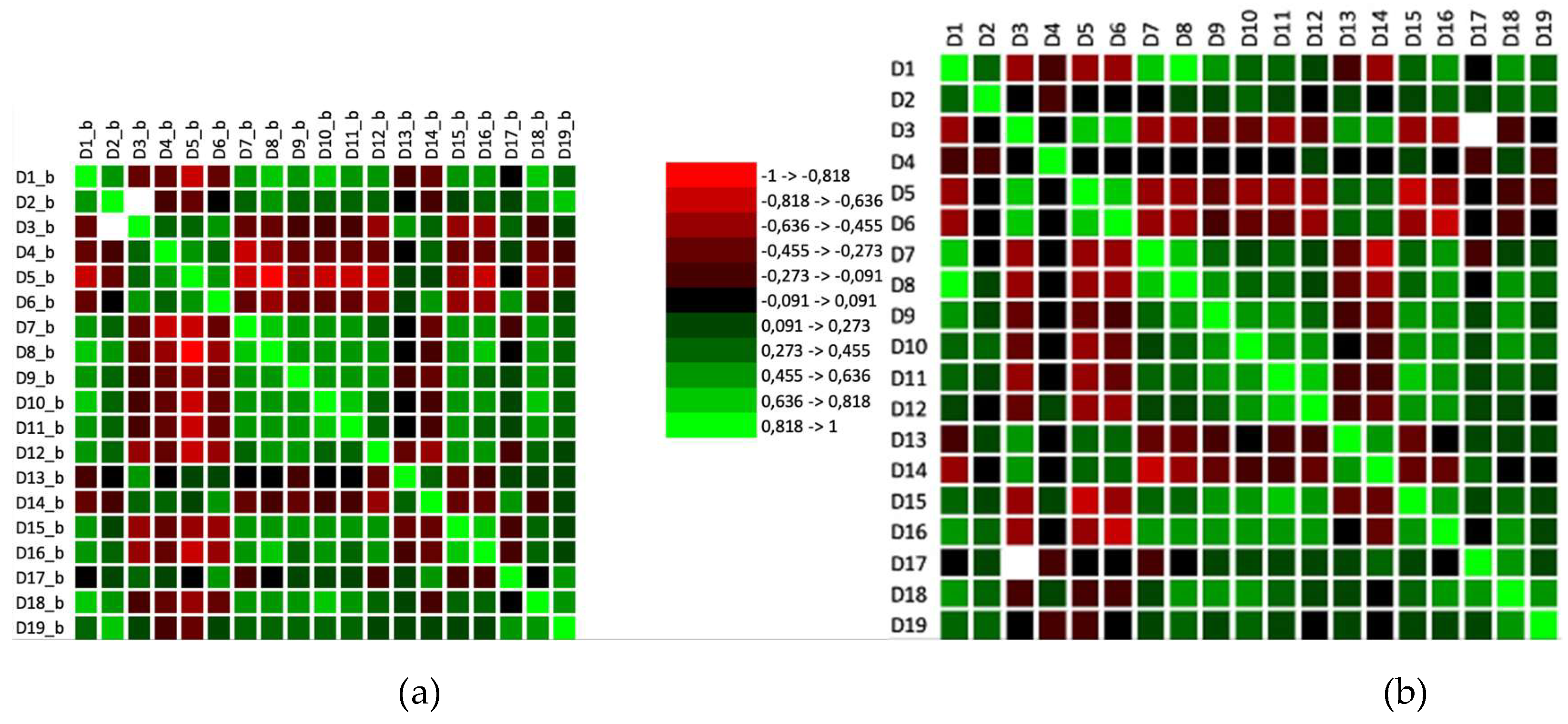

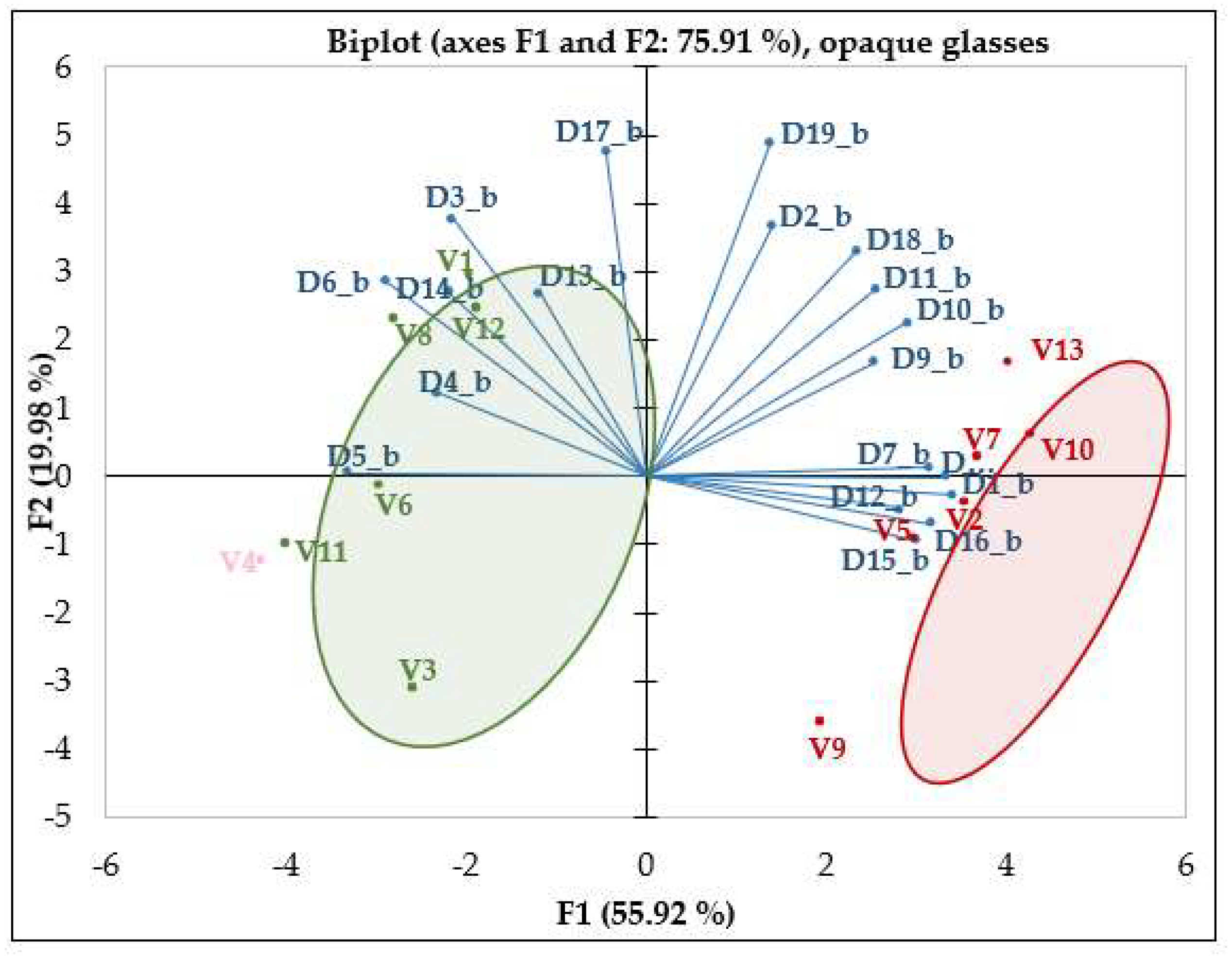

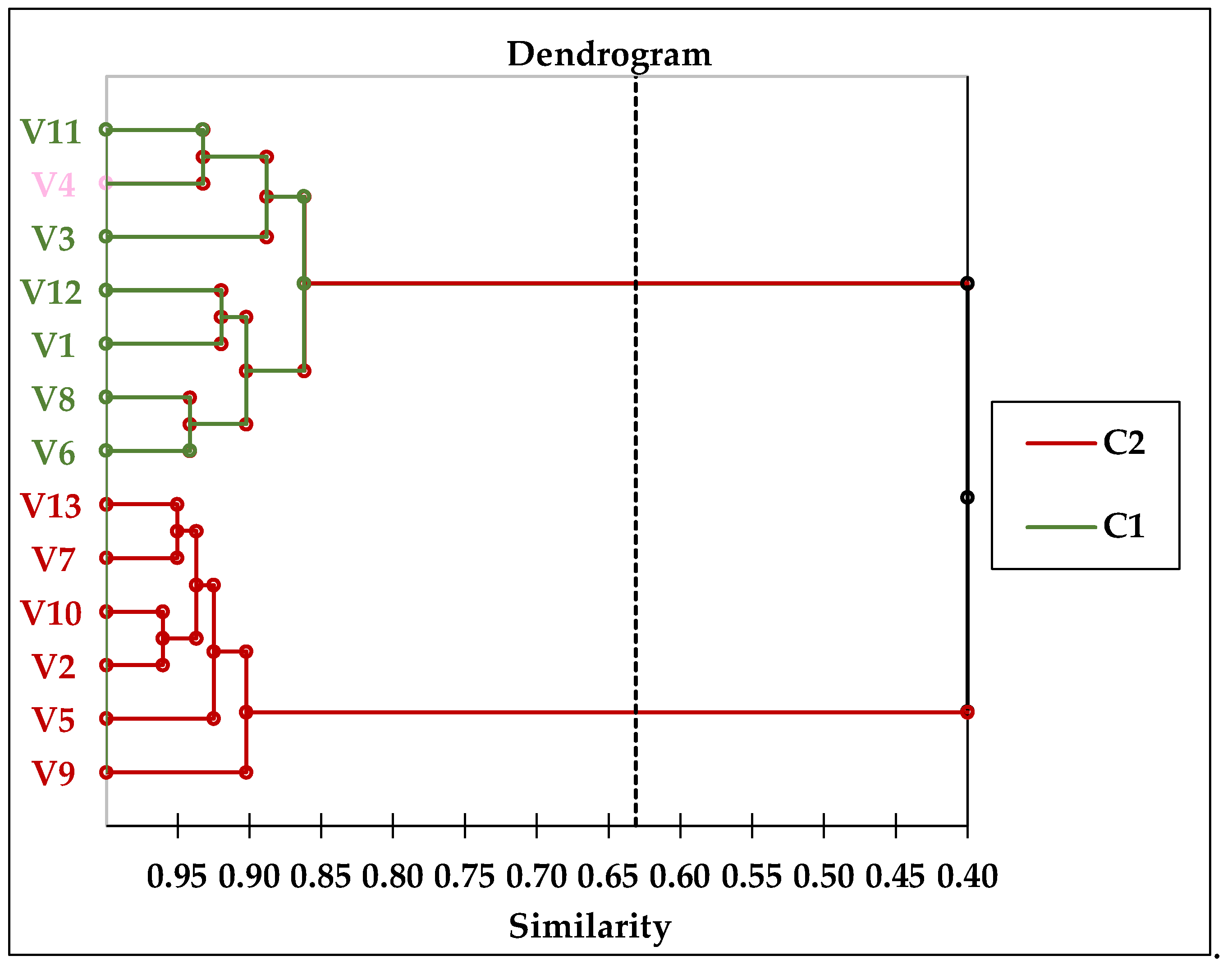

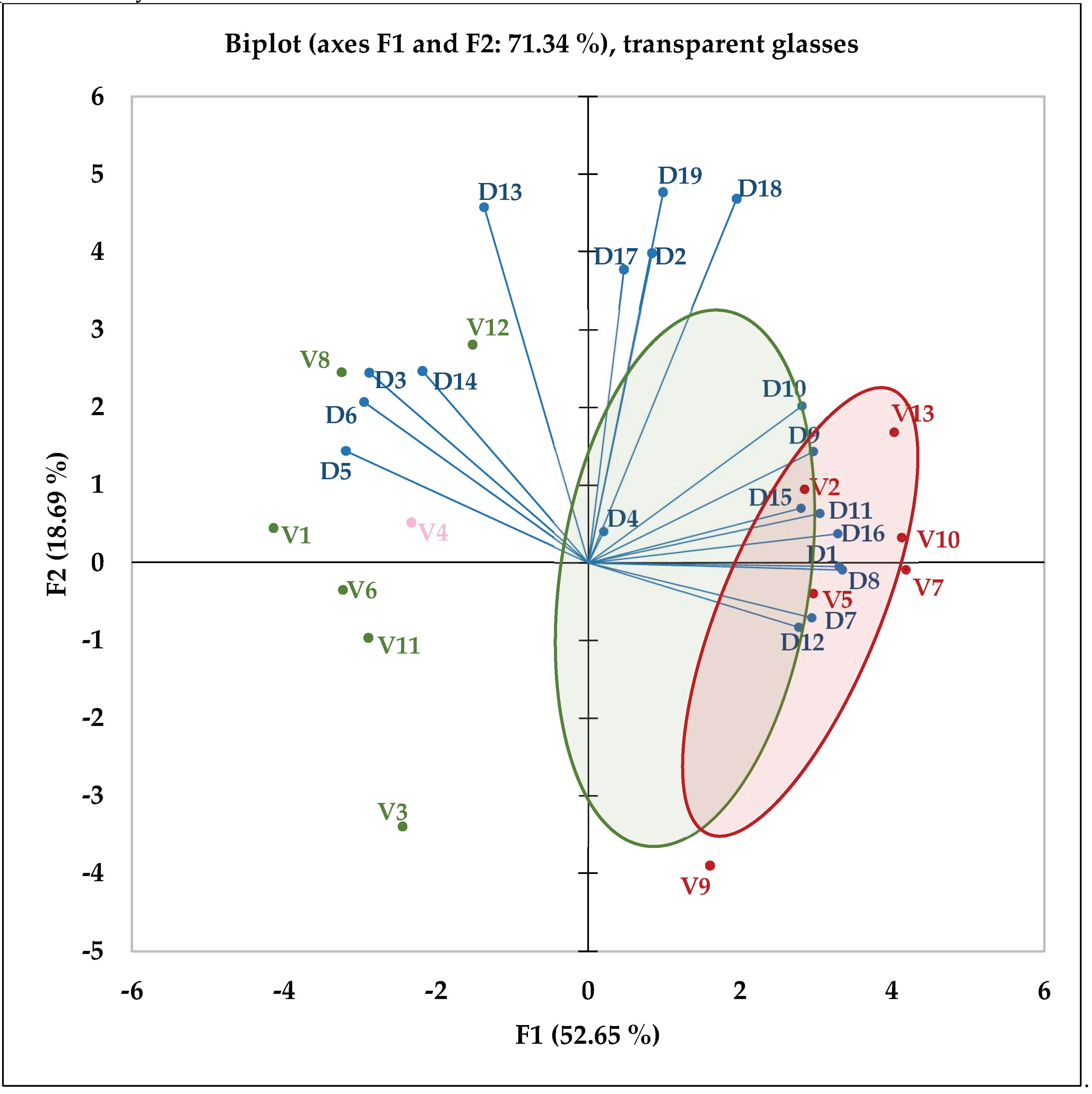

3.2. Data concerning the context of tasting sessions, whether using opaque or transparent glasses

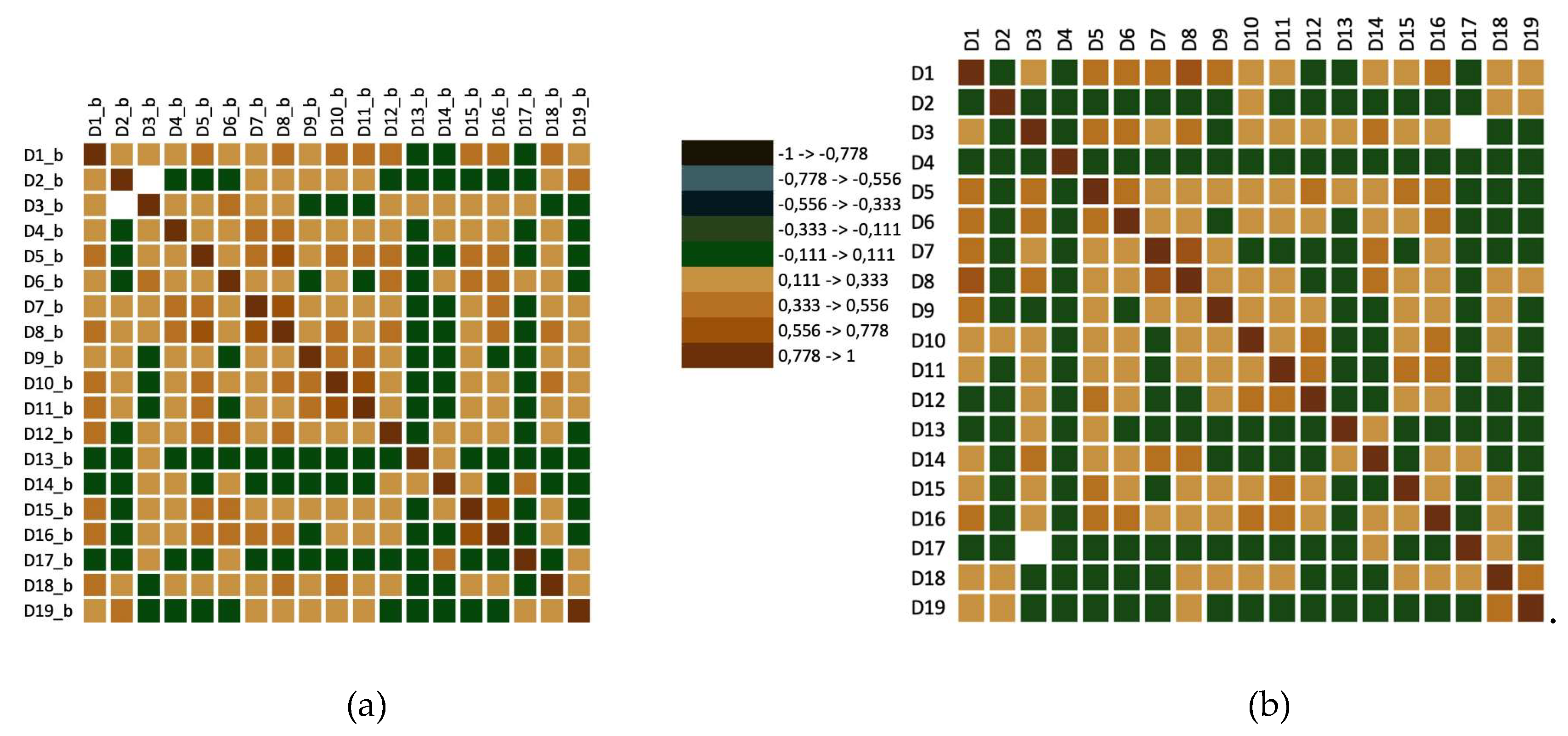

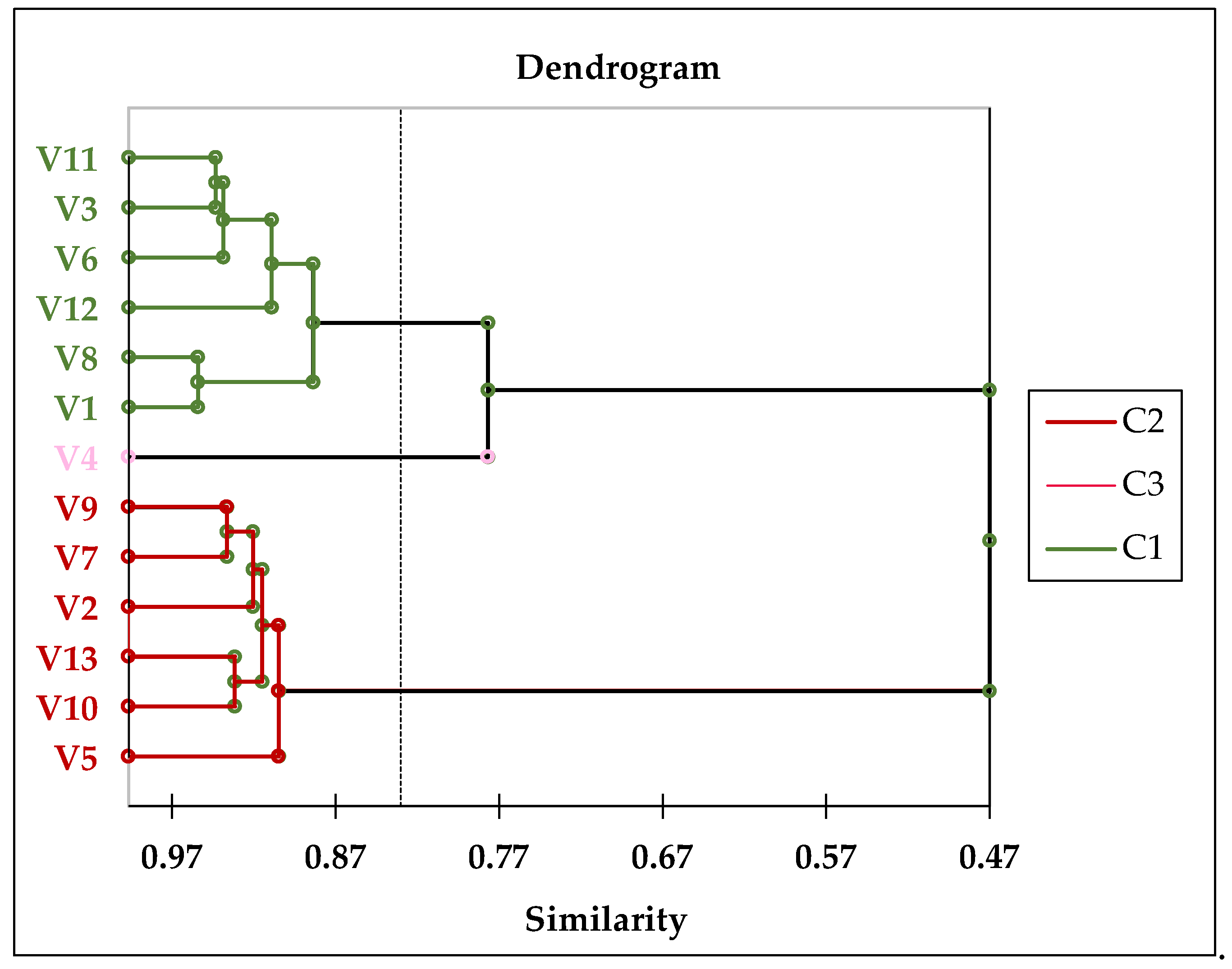

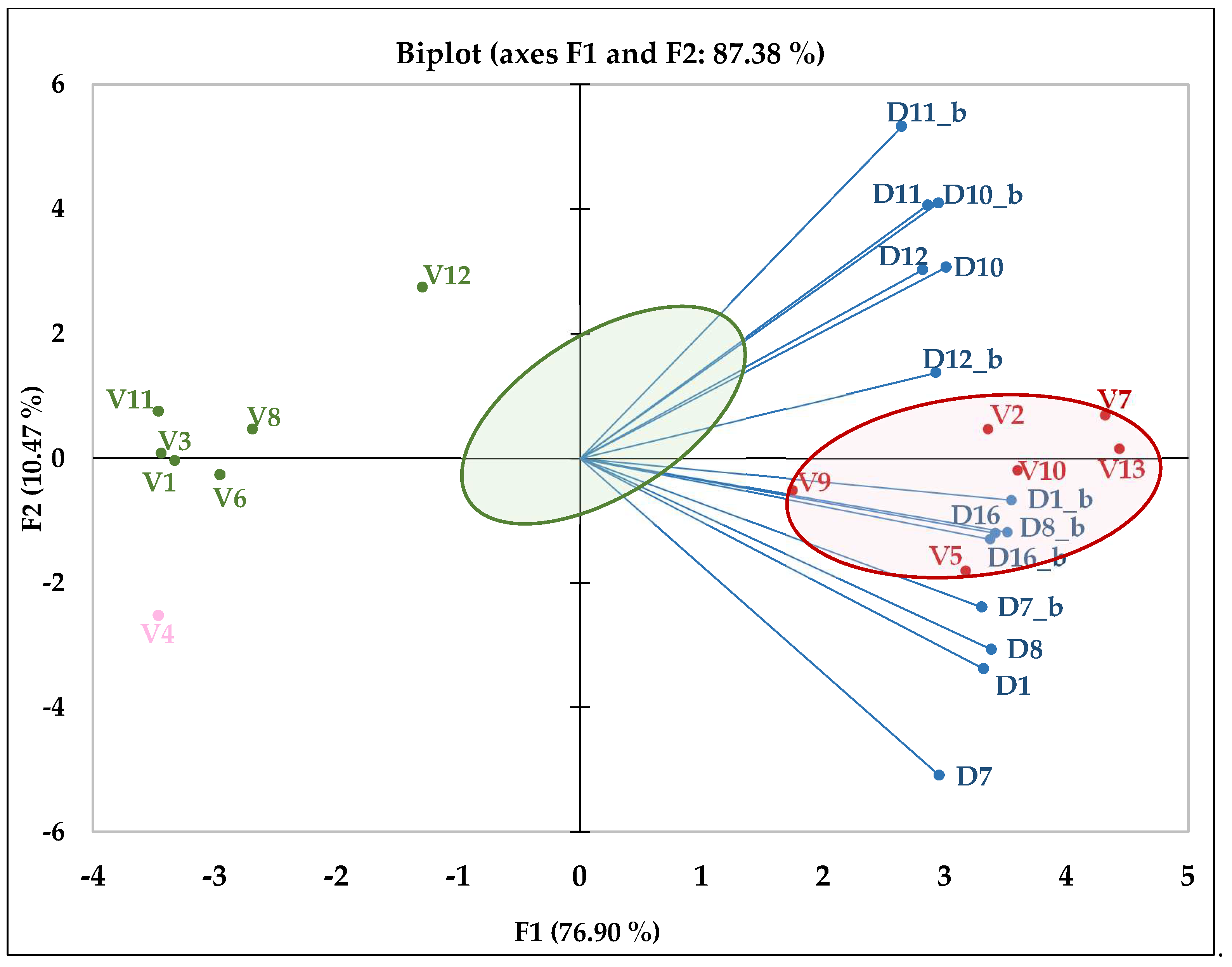

3.3. Data related to the context of the winemaking method

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of winemaking method on sensory perception

4.2. The influence of tasting context on sensory perception

5. Conclusions

Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. A. Zellner; A. M. Bartoli; R. Eckard. Influence of Color on Odor Identification and Liking Ratings. The American Journal of Psychology 1991, vol. 104, pp. 547—561.

- J. Ballester; A. Hervé; J. Langlois; D. Peyron; D. Valentin. The Odor of Colors: Can Wine Experts and Novices Distinguish the Odors of White, Red, and Rosé Wines?. Chemosensory Perception 2009, vol. 2, pp. 203—213.

- Cardello. Consumer expectations and their role in food acceptance. In Measurement of food preferences. MacFie, H., Thomson, D. London, Eds.; Elsevier: London, 1994; pp. 253—297.

- E. Voirol; N. Daget. Comparative study of nasal and retronasal olfactory perception. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft + Technologie 1986, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 316—319.

- M. Auvray; C. Spence. The multisensory perception of flavor. Consciousness and Cognition 2008, vol. 17, pp. 1016—1031.

- P. Dalton; N. Doolitle; H. Nagata; P. Breslin. The merging of the senses: Integration of subthreshold taste and smell. Nature Neuroscience 2000, vol. 3, pp. 431—432.

- Z. Temerdashev; A. Abakumov; A. Kaunova; O. Shelud'ko; T. Tsyupko. Assessment of Quality and Region of Origin of Wines. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2023, vol. 78, no. 12, pp. 1724—1740.

- R. Gutiérrez-Escobar; M. J. Aliaño—González; E. Cantos—Villar. Wine Polyphenol Content and Its Influence on Wine Quality and Properties: A Review. Molecules—MDPI 2021, vol. 26, no. 3, p. 718.

- B. Nemzer; D. Kalita; A. Y. Yashin; Y. I. Yashin. Chemical Composition and Polyphenolic Compounds of Red Wines: Their Antioxidant Activities and Effects on Human Health—A Review. Beverages 2022, vol. 8, no. 1.

- J. A. Gottfried; R. J. Dolan. The Nose Smells What the Eye Sees: Crossmodal Visual Facilitation of Human Olfactory Perception. Neuron 2003, vol. 39, pp. 375—386.

- W. V. Parr. Application of cognitive psychology to advance understanding of wine sensory evaluation and wine expertise. In Applied Psychology Research Trends. K.Kiefer, Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, 2008; pp. 55—76.

- S. Chu; J. J. Downes. Odour—evoked Autobiographical Memories: Psychological Investigations of Proustian Phenomena. Chemical Senses 2000, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 111—116.

- W. V. Parr. Demystifying wine tasting: Cognitive psychology's contribution. Food Research International 2019, vol. 124, pp. 230—233.

- E. P. Köster; P. Møller; J. Mojet. A “Misfit” Theory of Spontaneous Conscious Odor Perception (MITSCOP): reflections on the role and function of odor memory in everyday life. Frontiers in Psychology 2014, vol. 5.

- Anton Paar GmbH, https://www.anton-paar.com/corp-en/. Available online: https://www.anton-paar.com/corp-en/products/details/lyza-5000-wine/?srsltid=AfmBOoqXMtI_gxrWSnnbZ17Ctq2qVJP9loLK4y5QEAybcCYa6_EZl8XX. (Accessed on 02 05 2025).

- D. Cozzolino; R. Dambergs; L. Janik; W. Cynkar; M. Gishen. Analysis of grapes and wine by near infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Near Infrared Spectroscopy 2006, vol. 14, pp. 279—289.

- C. Patz; A. Blieke; R. Ristow; H. Dietrich. Application of FT—MIR spectrometry in wine analysis. Analytica Chimica Acta 2004, vol. 513, p. 81—89.

- WSET, Wine & Spirit Education Trust. Available online: https://www.wsetglobal.com/. (Accessed 04 May 2025).

- WSET, Wine & Spirit Education Trust, WSET Level 4 Systematic Approach to Tasting Wine® (2023, Issue 1.2). Available online: https://www.wsetglobal.com/knowledge-centre/wset-systematic-approach-to-tasting-sat/. (Accessed 16 April 2025).

- J. Harding; J. Robinson; T. Q. Thomas. The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2023.

- H. Lawless; M. P. Schlegel. Direct and Indirect Scaling of Sensory Differences in Simple Taste and Odor Mixtures. Journal of Food Science 1984, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 44—46.

- R. S. Jackson. Wine tasting - A professional handbook, 4th ed.; Nikki Levy: Chennai, India, 2023; p. 59.

- www.oiv.int, Available online: http://20.216.173.16/sites/default/files/import/tecnical_documents/ review-on-sensory-analysis-of-wine_en.pdf. (Accessed 01 May 2025).

- E. Qannari; P. Schlich; Matching sensory and instrumental data. Flavour in Food; Andree Voilley, Patrick Etievant, Eds; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, England, 2006; pp. 98—116.

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis/annex-a-methods-of-analysis-of-wines-and-musts/section-2-physical-analysis. (Accessed 15 May 2025).

- S. Lubbers; A. Voilley; M. Feuillat; C. Charpentier. Influence of Mannaproteins from Yeast on the Aroma Intensity of a Model Wine. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft & Technologie 1994, vol. 27, pp. 108—114.

- M. Cameleyre; C. Monsant; S. Tempere; G. Lytra; J.-C. Barbe. Toward a Better Understanding of Perceptive Interactions between Volatile and Nonvolatile Compounds: The Case of Proanthocyanidic Tannins and Red Wine Fruity Esters—Methodological, Sensory, and Physicochemical Approaches. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2021, vol. 69, pp. 9895—9904.

- L. Robinson; S. E. Ebeler; H. Heymann; P. K. Boss; P. S. Solomon; R. D. Trengove. Interactions between wine volatile compounds and grape and wine matrix components influence aroma compound headspace partitioning. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2009, vol. 57, pp. 10313—10322.

- Voilley; V. Beghin; C. Charpentier; D. Peyron. Interactions between aroma substances and macromolecules in a model wine. Lebensmittel - Wissenschaft + Technologie 1991, vol. 24, pp. 469—472.

- J. Marais; C. Van Wyk. Effect of grape maturity and juice treatments on terpene concentrations and wine quality of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Weisser Riesling and Bukettraube. South African Journal of Enology & Viticulture 1986, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 26—35.

- Dunkel; M. Steinhaus; M. Kotthoff; B. Nowak; D. Krautwurst; P. Schieberle; T. Hofmann. Nature’s Chemical Signatures in Human Olfaction: A Foodborne Perspective for Future Biotechnology. Angewandte Chemie 2014, vol. 53, pp. 7124—7143.

- V. Ferreira; A. De La Fuente-Blanco; M. P. Saénz-Navajas. A New Classification of Perceptual Interactions between Odorants to Interpret Complex Aroma Systems. Application to Model Wine Aroma. Foods 2021, vol. 10, 1627.

- V. Ferreira; A. De La Fuente; M. P. Saénz-Navajas. Wine aroma vectors and sensory attributes. In Managing Wine Quality, 2nd ed; Woodhead Publishing Series: Cambridge, UK, 2022; vol. 1 Viticulture and Wine Quality, pp. 3—39.

- Y. Ma; Y. Xu; K. Tang. Olfactory perception complexity induced by key odorants perceptual interactions of alcoholic beverages: Wine as a focus case example. Food Chemistry 2025, vol. 463.

- G. Reynolds. Managing Wine Quality, Woodhead Publishing Series: Cambridge, UK, 2022, vol. 1 Viticulture and Wine Quality.

- J. Moini; A. Logalbo; R. Ahangari. Sensation and Perception. Foundations of the Mind, Brain, and Behavioral Relationships Understanding Physiological Psychology 1st ed.; Nikki P. Levy: London, 2024, p. 115.

- Lesschaeve. Sensory Evaluation of Wine and Commercial Realities: Review of Current Practices and Perspectives. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2007, vol. 58, pp. 252—258.

- F. Brochet; D. Dubourdieu. Wine Descriptive Language Supports Cognitive Specificity of Chemical Senses. Brain and Language 2001, vol. 77, pp. 187—196.

- T. H. Nguyen; D. Durner. Sensory evaluation of wine aroma: Should color—driven descriptors be used?. Food Quality and Preference 2023, vol. 107.

- Mateo; M. Jiménez. Monoterpenes in grape juice and wines. Journal of Chromatography 2000, vol. 881, no. 1—2, pp. 557—567.

- Delwiche. The impact of perceptual interactions on perceived flavor. Food Quality and Preference 2004, vol. 15, pp. 137—146.

- G. Morrot, F. Brochet and D. Dubourdieu. The Color of Odors. Brain and Language 2001, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 309—320.

| ID | Vintage | Grape Variety | Vinified | Winery | Region |

| V1 | 2021 | Bobal | Blanc de noir | Vicente Gandia | ES–Utiel Requena |

| V2 | 2020 | Bobal | Red | Vicente Gandia | ES–Utiel Requena |

| V3 | 2021 | Cabernet Sauvignon | Blanc de noir | Rojevas Agroinvest | RO–Târgu Bujor |

| V4 | 2022 | Cabernet Sauvignon | Rosé | Rojevas Agroinvest | RO–Târgu Bujor |

| V5 | 2021 | Cabernet Sauvignon | Red | Rojevas Agroinvest | RO–Târgu Bujor |

| V6 | 2021 | Cabernet Sauvignon | Blanc de noir | Domaine Vinarte | RO–Sâmburești |

| V7 | 2017 | Cabernet Sauvignon | Red | Domaine Vinarte | RO–Sâmburești |

| V8 | 2019 | Tinta Negra | Blanc de noir | Diana Silva Wines | PT–Madeira |

| V9 | 2019 | Tinta Negra | Red | Diana Silva Wines | PT–Madeira |

| V10 | 2019 | Tinta Roriz | Red | Quinta do Vallado | PT–Douro |

| V11 | 2021 | Tinta Roriz | Blanc de noir | Quinta Nova | PT–Alto Douro |

| V12 | 2021 | Touriga Franca (95%) | Blanc de noir | Ravasqueira | PT–Alentejo |

| V13 | 2020 | Touriga Franca (95%) | Red | Ravasqueira | PT–Alentejo |

| Conventional ordinal number allocated in the representation of statistical values* | Descriptor title | Description of the specific features / notes appraised by descriptor |

References |

| 1 | Existence of a maceration stage and perceived intensity of it | Presumed exclusively based on orthonasal olfactory stimuli in tasting sessions with opaque glasses. | – |

| 2 | Overall olfactory intensity | Exclusively based on orthonasal olfactory stimuli. | – |

| 3 | Floral notes | Blossom notes, consisting in elderflower, honeysuckle, jasmine, rose, violet, acacia, chamomile, linden, honey, geranium odors/aromas | [19] |

| 4 | Vegetal/herbal notes | Eucalyptus, mint, fennel, dill, dried herbs thyme, oregano, lavender odors/aromas | [19] |

| 5 | ‘Green’/fresh/citrus fruits | Apple, pear, gooseberry, grape–fruit, orange, grape odors/aromas | [19] |

| 6 | Exotic fruits/ stone fruits/ tropical fruits | Peach, apricot, nectarine, plum_banana, melon, watermelon, passion fruit, pineapple odors/aromas | [19] |

| 7 | Red fruits | Redcurrant, cranberry, raspberry, strawberry, red cherry, red plum, pomegranate odors/aromas | [19] |

| 8 | Berries/forest fruits | Opaquecurrant, opaqueberry, blueberry, opaque cherry, opaque plum, sour–cherry odors/aromas | [19] |

| 9 | Overripe fruits | Figs, dried plums, raisins, prune, jam odors/aromas | [19] |

| 10 | Spice notes | Cinnamon, pepper, cloves, saffron, vanilla, coconut, liquorice, cedar, nutmeg, anise odors/aromas | [19] |

| 11 | Maillard–type notes | Roasted hazelnut/walnut, almond, coal smoke, cocoa, coffee, caramel, chocolate, toast, resins, tobacco odors/aromas. | – |

| 12 | Other specific notes | Leather, tanned leather, mushrooms, wet stone, flint, red earth, eucalyptus odors/aromas | [19] |

| 13 | Acidity/sourness | Fresh or sour taste produced by the natural organic acids, one of the primary tastes sensed by tastebuds on the tongue | [20] |

| 14 | Sweetness | One of the primary tastes involved in tasting, mainly because of the amount of residual sugar they contain | [20] |

| 15 | Bitterness | Among primary tastes which can be detected via taste buds mainly on the tongue , often confused with the quite different tactile sensation caused by astringency | [20] |

| 16 | Astringency | A complex tactile response resulting from shrinking, drawing, or puckering of the tissues of the mouth, based in principle by binding between tannins with proteins | [20] |

| 17 | Unctuousness | More a perceptual descriptor to describe the physical property of viscosity understood as the quality sensed by the human palate in the form of resistance as the solution is rinsed around the mouth | [20] |

| 18 | Finish/post–taste persistence |

Somehow derided tasting term to appraise the persistency of flavour and the impact of the wines on the palate, supposed to be direct proportional with some colloids | [20] |

| 19 | Overall evaluation | Based on summarizing all previous personal sensory judgments | – |

| Parameter | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | ||||||

| Ethanol (% vol) | 12.24±0,00 | 14.42±0,01 | 12.08±0,00 | 13.84±0,01 | 11.36±0,00 | 12.8±0,00 | 14.32±0,00 | ||||||

| Glucose+Fructose (g/L) | 0.90±0.02 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.80±0.03 | 6.80±0.02 | n/d±0.00 | 0.90±0.00 | 0.50±0.02 | ||||||

| Titratable acidity (g/L*) | 4.73±0.00 | 4.64±0.00 | 4.57±0.00 | 6.85±0.01 | 5.5±0.01 | 4.79±0.00 | 4.69±0.00 | ||||||

| Volatile acidity (g/L**) | 0.46±0.01 | 0.69±0.01 | 0.38±0.00 | 0.33±0.00 | 0.78±0.01 | 0.37±0.01 | 1.13±0.01 | ||||||

| Malic acid (g/L) | 1.09±0.01 | n/d±0.00 | 1.33±0.02 | 1.78±0.02 | n/d±0.00 | 0.68±0.01 | n/d±0.01 | ||||||

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 1.11±0.00 | 1.58±0.01 | 0.99±0.00 | 2.62±0.02 | 1.81±0.00 | 1.69±0.00 | 1.13±0.00 | ||||||

| Lactic acid (g/L) | 0.63±0.00 | 1.22±0.01 | 0.65±0.00 | n/d±0.00 | 1.93±0.00 | 0.26±0.00 | 1.53±0.01 | ||||||

| pH | 3.40±0.01 | 3.56±0.01 | 3.47±0.01 | 3.11±0.00 | 3.56±0.01 | 3.34±0.02 | 3.67±0.01 | ||||||

| Density (g/mL) | 0.9915±0.01 | 0.9910±0.00 | 0.9913±0.00 | 0.9922±0.01 | 0.9950±0.01 | 0.9887±0.00 | 0.9919±0.01 | ||||||

| Total dry extract (g/L) | 24.50±0.01 | 29.60±0.02 | 23.40±0.00 | 30.80±0.00 | 30.70±0.00 | 18.90±0.01 | 31.60±0.01 | ||||||

| Glycerol (g/L) | 8.00±0.00 | 9.30±0.00 | 7.00±0.01 | 6.70±0.00 | 9.30±0.02 | 6.60±0.01 | 9.90±0.01 | ||||||

| Polyphenols–total (mg/L) | 1.28±0.00 | 2.08±0.00 | 0.49±0.00 | 1.22±0.00 | 2.64±0.00 | 0.87±0.00 | 2.27±0.00 | ||||||

| Parameter | V8 | V9 | V10 | V11 | V12 | V13 | |||||||

| Ethanol (% vol) | 11.66±0,00 | 11.44±0,01 | 14.43±0,01 | 12.55±0,00 | 12.43±0,01 | 14.58±0,00 | |||||||

| Glucose+Fructose (g/L) | 0.30±0.02 | n/d±0.00 | n/d±0.00 | 0.40±0.01 | 0.70±0.02 | 0.40±0.01 | |||||||

| Titratable acidity (g/L*) | 6.37±0.00 | 5.09±0.00 | 4.19±0.00 | 5.33±0.01 | 5.13±0.01 | 4.66±0.00 | |||||||

| Volatile acidity (g/L**) | 0.43±0.01 | 0.74±0.01 | 0.77±0.01 | 0.41±0.00 | 0.38±0.01 | 0.88±0.00 | |||||||

| Malic acid (g/L) | 2.11±0.02 | n/d±0.00 | 0.15±0.00 | 1.95±0.01 | 1.22±0.01 | n/d±0.00 | |||||||

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 2.11±0.01 | 1.77±0.01 | 0.51±0.00 | 1.12±0.00 | 1.49±0.01 | 1.30±0.00 | |||||||

| Lactic acid (g/L) | n/d±0.00 | 2.08±0.01 | 1.55±0.00 | 0.05±0.00 | 0.22±0.00 | 1.45±0.00 | |||||||

| pH | 3.20±0.01 | 3.47±0.01 | 3.66±0.00 | 3.35±0.01 | 3.33±0.01 | 3.62±0.02 | |||||||

| Density (g/mL) | 0.9895±0.02 | 0.9920±0.01 | 0.9902±0.00 | 0.9883±0.00 | 0.9891±0.01 | 0.9905±0.01 | |||||||

| Total dry extract (g/L) | 17.50±0.01 | 23.30±0.01 | 27.40±0.02 | 17.10±0.00 | 18.80±0.01 | 28.80±0.01 | |||||||

| Glycerol (g/L) | 5.70±0.00 | 8.30±0.00 | 9.60±0.00 | 5.70±0.01 | 6.30±0.00 | 9.70±0.01 | |||||||

| Polyphenols–total (mg/L) | 0.64±0.00 | 1.80±0.00 | 2.00±0.00 | n/d±0.00 | 0.75±0.00 | 1.90±0.00 | |||||||

| ID Parameter | W | p–value | R² | F_statistic | Pr > F | Signification |

| D1_b | 0.984 | 0.843 | 0.842 | 11.537 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D1 | 0.959 | 0.162 | 0.885 | 16.745 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D2_b | 0.984 | 0.835 | 0.579 | 2.978 | 0.010 | ** |

| D2 | 0.970 | 0.383 | 0.311 | 0.978 | 0.493 | ∞ |

| D3_b | 0.977 | 0.585 | 0.489 | 2.070 | 0.059 | . |

| D3 | 0.981 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 2.167 | 0.048 | * |

| D4_b | 0.967 | 0.306 | 0.592 | 3.138 | 0.007 | ** |

| D4 | 0.958 | 0.148 | 0.249 | 0.720 | 0.720 | ∞ |

| D5_b | 0.954 | 0.110 | 0.645 | 3.943 | 0.002 | ** |

| D5 | 0.944 | 0.050 | 0.657 | 4.154 | 0.001 | ** |

| D6_b | 0.962 | 0.201 | 0.595 | 3.180 | 0.007 | ** |

| D6 | 0.990 | 0.971 | 0.353 | 1.184 | 0.344 | ∞ |

| D7_b | 0.986 | 0.907 | 0.815 | 9.533 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D7 | 0.989 | 0.966 | 0.867 | 14.140 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D8_b | 0.984 | 0.858 | 0.917 | 23.878 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D8 | 0.986 | 0.890 | 0.941 | 34.266 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D9_b | 0.962 | 0.203 | 0.564 | 2.804 | 0.013 | * |

| D9 | 0.955 | 0.126 | 0.306 | 0.954 | 0.513 | ∞ |

| D10_b | 0.966 | 0.278 | 0.578 | 2.963 | 0.010 | ** |

| D10 | 0.967 | 0.301 | 0.723 | 5.649 | 0.000 | *** |

| D11_b | 0.983 | 0.818 | 0.767 | 7.130 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D11 | 0.956 | 0.134 | 0.576 | 2.943 | 0.010 | * |

| D12_b | 0.981 | 0.756 | 0.753 | 6.614 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D12 | 0.983 | 0.794 | 0.531 | 2.451 | 0.027 | * |

| D13_b | 0.984 | 0.829 | 0.276 | 0.827 | 0.623 | ∞ |

| D13 | 0.939 | 0.036 | 0.164 | 0.426 | 0.939 | ∞ |

| D14_b | 0.962 | 0.201 | 0.448 | 1.759 | 0.111 | ∞ |

| D14 | 0.968 | 0.315 | 0.246 | 0.708 | 0.730 | ∞ |

| D15_b | 0.972 | 0.430 | 0.623 | 3.583 | 0.003 | ** |

| D15 | 0.979 | 0.677 | 0.516 | 2.307 | 0.036 | * |

| D16_b | 0.970 | 0.370 | 0.828 | 10.401 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D16 | 0.979 | 0.653 | 0.886 | 16.831 | <0.0001 | *** |

| D17_b | 0.976 | 0.553 | 0.231 | 0.651 | 0.780 | ∞ |

| D17 | 0.910 | 0.004 | 0.200 | 0.543 | 0.866 | ∞ |

| D18_b | 0.965 | 0.262 | 0.481 | 2.009 | 0.066 | . |

| D18 | 0.971 | 0.401 | 0.381 | 1.333 | 0.260 | ∞ |

| D19_b | 0.924 | 0.012 | 0.704 | 5.159 | 0.000 | *** |

| D19 | 0.968 | 0.315 | 0.460 | 1.842 | 0.093 | . |

|

Muscat varieties > 6 mg/L |

Non–Muscat, aromatic varieties 1 – 4 mg/L |

Neutral varieties < 1 mg/L |

| Canada Muscat | Traminer | Bacchus |

| Gewürztraminer | Huxelrebe | Chardonnay |

| Muscat of Alexandria | Kerner | Chasselas |

| Muscat blanc à petits grains | Morio–Muskat | Chenin blanc |

| Moscato Bianco | Müller–Thurgau | Clairette |

| Muscat Ottonel | Riesling | Nobling |

| Moscato Italiano | Scheurebe | Rkatsiteli |

| Siegerrebe | Sauvignon blanc | |

| Sylvaner | Sémillon | |

| Würzer | Sultana | |

| Italian Riesling | Trebbiano | |

| Verdelho | ||

| Viognier | ||

| Vidal blanc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).