1. Introduction

The increasing use of virtual humans in education, healthcare, cultural communication, and immersive interaction has established emotional expressiveness as a key metric for assessing interaction quality and user experience. Beyond basic expression mapping and emotion classification, real-world applications require virtual agents to convey emotions with greater granularity, diversity, and dynamic intensity—fostering trust, empathy, and emotional resonance [

1,

2].

Micro-expressions, brief (1/25 to 1/5 second) involuntary facial muscle movements, are critical nonverbal cues for identifying concealed or suppressed emotions [

3]. Their transient and involuntary nature makes them highly effective in revealing subtle emotional states. Recent studies have shown that such fine-grained signals are essential for affective evaluation in multimodal systems—including EEG, eye-tracking, and virtual reality [

4,

5] —highlighting their value in enhancing the perceptual realism of emotionally responsive virtual agents.

However, most existing virtual human systems rely on macro-expression-driven skeletal templates [3], which are insufficient for capturing nuanced facial dynamics or rapid emotional transitions. These limitations result in coarse expression granularity, reduced variation, and restricted emotional range, impairing the system’s ability to render subtle affective changes—especially in high-fidelity interaction scenarios.

In the domain of micro-expression research, recognition and generation are typically addressed as separate tasks, lacking an integrated pipeline that connects video-based emotion perception, structural modeling, and animation synthesis. Moreover, few methods account for the structured dependencies among Action Units (AUs, standardized descriptors of facial muscle movements) or incorporate continuous emotion intensity modulation. This fragmented architecture reduces the responsiveness, realism, and expressive depth of virtual humans in dynamic, context-aware settings.

To bridge this gap, we propose a unified micro-expression modeling and 3D animation framework that enables end-to-end synthesis of expressive facial behavior. The system comprises three main components:

Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction: A 3D-ResNet-18 network—a convolutional architecture designed for capturing spatiotemporal patterns—is employed to extract motion-aware features from video sequences and identify the onset, apex, and offset frames of micro-expressions.

Structural Dependency Modeling: A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is constructed using a directed and asymmetric adjacency matrix derived from AU co-occurrence probabilities, enabling the model to capture interdependent facial activations.

3D Animation Synthesis: Recognized expression sequences are converted into continuous animation control curves, driving the facial rig in Unreal Engine, a widely used real-time 3D rendering engine, to generate fine-grained, high-fidelity facial animations.

To validate the framework, we conducted a perceptual study evaluating the synthesized facial expressions across three dimensions: clarity, naturalness, and authenticity. Results demonstrate that our system significantly improves emotional recognizability and visual realism, particularly in distinguishing similar negative emotions such as fear and disgust.

In summary, this work presents an integrated framework that combines micro-expression recognition, AU-based structural modeling, and high-resolution animation synthesis. By addressing both temporal localization and structural dependencies, the system advances controllable, emotionally differentiated, and perceptually realistic facial animation for virtual humans, offering a scalable solution for affective computing and immersive human–machine interaction.

2. Related Work

2.1. Trends in Micro-Expression Recognition

Micro-expressions—brief facial movements lasting less than 0.5 seconds [

6] with low intensity—remain a major challenge in visual behavior analysis.Early research relied on handcrafted descriptors such as Local Binary Patterns on Three Orthogonal Planes (LBP-TOP) [

7], Histogram of Oriented Optical Flow (HOOF) [

8], and traditional optical flow methods. While these techniques [

9,

10] yielded reasonable performance in controlled settings (e.g., Zhao et al. on the CASME II dataset [

11]), they exhibit limited robustness to illumination variation, head motion, and dynamic interactions among facial Action Units (AUs), restricting their applicability in real-world scenarios.

With the emergence of deep learning, micro-expression recognition has made significant strides. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models [

12,

13] improved the modeling of temporal dependencies between facial regions, facilitating the learning of dynamic AU relationships. Recently, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

14] have been employed to model AU co-activation patterns by constructing AU-centric graph structures. Zhao et al. [

15] and Lo et al [

16] . demonstrated the potential of GCNs for this task, though their integration into full recognition pipelines remains limited.

End-to-end convolutional approaches have also been explored. Wang et al. [

17] utilized a combination of 2D-CNN and 1D-CNN to extract spatial and temporal features, refining temporal localization; Zhang et al [

18]. enhanced temporal proposal accuracy; Yap et al. [

19] adopted 3D-CNNs for joint spatiotemporal modeling; and Leng et al. [

20] introduced Boundary-Sensitive Networks (BSNs) to accommodate blended macro- and micro-expressions. Nevertheless, most existing methods still focus on basic emotion categories and fail to adequately model complex emotional states, subtle facial variations, and inter-individual differences.

Traditional animation pipelines typically rely on static blendshape interpolation, which cannot capture the nuanced dynamics of AU interactions or represent the diversity of human emotional expressions. Moreover, emerging generative architectures, such as Transformer-based models and diffusion networks, have not yet been systematically applied to micro-expression modeling.

To bridge this gap, we propose a unified framework that integrates micro-expression recognition and synthesis using AU-guided graph modeling. Specifically, we construct directed graphs based on AU co-occurrence probabilities to represent AU dependencies, and combine GCN-based structural inference with temporal feature encoding. This enables the generation of diverse and temporally aligned emotional trajectories. The proposed approach addresses the limitations of prior work in capturing fine-grained emotional dynamics and provides a robust pathway for high-realism and expressive facial animation in virtual humans.

2.2. AU Detection

Action Units (AUs), the fundamental components of the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) [

21], represent subtle facial muscle movements and offer a physiologically grounded approach to describing fine-grained expressions. Compared to the direct classification of discrete emotion categories, AU-based detection captures specific muscle activations, thereby improving interpretability and reducing annotation bias. This provides a structured foundation for micro-expression recognition and affective modeling.

Early AU detection methods focused on static appearance features such as facial textures and keypoints. However, these approaches are limited in capturing the temporal dynamics and nonlinear co-activation patterns among multiple AUs, especially in micro-expressions, which are brief and involve complex muscular interactions. Deep learning techniques have significantly advanced AU detection. Models based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have demonstrated strong capabilities in learning subtle muscle dynamics. For example, Liu et al. [

14] modeled AU co-activation relationships using GCNs, enhancing both detection robustness and cross-dataset generalization.

Despite these developments, three key challenges persist. First, the lack of large-scale, high-quality AU-labeled datasets limits generalizability. Second, most existing methods treat AU relationships as static, ignoring the time-varying and asymmetric interactions that characterize spontaneous micro-expressions. Third, current approaches typically do not establish a structured mapping from AU detection to animation control, making it difficult to synthesize emotionally diverse and expressive behaviors.

2.3. Micro-Expression Modeling in Virtual Humans

Micro-expression modeling aims to transform recognized subtle facial signals into a stream of animation control parameters. The core challenges lie in ensuring temporal accuracy, dynamic naturalness, and controllability within 3D animation pipelines.

Several representative systems—such as SARA [

22], ARIA [

23], and Coface [

24]—have explored expressiveness and interactivity to some extent. However, they suffer from limited control over fine-grained facial details. For instance, SARA [

22] utilizes the Behavior Markup Language (BML) to control facial states and supports the synthesis of basic emotions. Nevertheless, it lacks granularity in modeling subtle muscular transitions and exhibits rigidity in facial expression transitions. The ARIA [

23] platform adopts a modular design that separates input processing, agent generation, and animation output. Despite this structured architecture, its output still heavily depends on predefined motion templates, making it difficult to accurately reproduce realistic micro-facial dynamics.

Moreover, while recent advances in animation generation have benefited from large-scale algorithmic models, the physical realism of micro-expression modeling remains an underexplored area, requiring further investigation.

2.4. Comparative Analysis and Methodological Innovations

Despite notable progress in micro-expression recognition, most existing methods focus on either temporal localization or emotion classification, without offering a unified mechanism to directly integrate with virtual human facial animation systems. Moreover, current animation pipelines typically rely on static expression templates or pre-defined blendshapes, which are inadequate for modeling the dynamic interplay and nuanced transitions among facial action units (AUs), often resulting in rigid and emotionally unconvincing expressions.

2.4.1. Methodological Innovations

To address these limitations, this study proposes a unified, closed-loop framework that links micro-expression recognition, temporal segmentation, and facial animation control into an end-to-end process. This end-to-end system facilitates the seamless integration of AU-based emotion recognition, temporal segmentation, and 3D facial animation synthesis. The proposed framework introduces three core innovations:

Graph-Based Modeling of Action Units: Each AU is represented as a node in an asymmetric adjacency matrix, enabling the model to capture the inherent structural dependencies among facial muscles. A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) built upon AU co-occurrence statistics is employed to strengthen the structural sensitivity and generalization capability of the recognition process.

Joint Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction: To simultaneously capture spatial configurations and temporal dynamics, a 3D-ResNet-18 backbone is adopted. To enhance the modeling of subtle temporal variations, the backbone is further integrated with an Enhanced Long-term Recurrent Convolutional Network (ELRCN), thereby improving the sensitivity to transient and low-intensity motion cues, which are critical for micro-expression analysis.

Emotion-Driven Animation Mapping Mechanism: The extracted AU activation patterns are mapped into parameterized facial muscle trajectories via continuous motion curves, which in turn drive the expression synthesis module of the virtual human. This mapping strategy enables the generation of contextually appropriate and emotionally expressive facial animations, exceeding the expressive capacity of traditional template-based methods.

In summary, this work marks a significant step forward in bridging micro-expression recognition and high-fidelity animation synthesis, paving the way for emotionally responsive and behaviorally coherent virtual human systems. It not only enhances recognition accuracy and temporal precision but also establishes a controllable, closed-loop animation generation paradigm grounded in fine-grained AU dynamics.

2.4.2. Architectural Innovations

In recent years, many studies have employed CNNs to extract spatial features from individual frames, while incorporating Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) or Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) structures to model temporal dependencies across frames [

25], thereby capturing the dynamic evolution of facial movements. Others have adopted feature aggregation and encoding strategies such as bilinear models, VLAD, and Fisher encoding [

23,

26]. These networks commonly use three-dimensional convolutional and pooling kernels, extending conventional 2D spatial operations into the temporal dimension

t, to directly model spatiotemporal features in video sequences.

For example, in optical flow-based CNNs, the temporal kernel size

d is often set to 10. Tran et al. [

27] explored 3D CNNs with kernel sizes of

and extended the ResNet architecture using 3D convolutions. Feichtenhofer et al. [

28] further proposed a 3D spatiotemporal pooling strategy. Sun et al. [

29] decomposed 3D convolutions into 2D spatial and 1D temporal convolutions to reduce computational complexity while preserving modeling capacity. Carreira et al. [

30] proposed inflating a pre-trained 2D Inception-V1 architecture into 3D by extending all filters and pooling kernels along the temporal dimension

d.

However, in practical applications, the varying number of frames across video sequences poses challenges for direct temporal modeling. To address alignment issues, time normalization techniques are often employed to produce fixed-length sequences. Pfister et al. [

31] introduced a popular normalization algorithm—Temporal Interpolation Model (TIM)—which maps video frames along a time-constrained manifold. At the feature level, frame-wise features are aggregated to form a unified representation.

Inspired by these studies, our proposed system adopts a two-stage architecture for micro-expression analysis:

Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction: Given that micro-expressions (MEs) are brief (<0.5s) and subtle in amplitude, we utilize a lightweight yet effective backbone—3D-ResNet-18—for end-to-end modeling of video segments. The 3D Convolutional Neural Network (3D-CNN) slides jointly across spatial (

x,

y) and temporal (

t) dimensions, enabling the network to perceive fine-grained motion variations between consecutive frames. This makes it particularly suitable for temporally sensitive and low-amplitude signals such as MEs [

27]. Additionally, the Enhanced Long-term Recurrent Convolutional Network (ELRCN) [

32] incorporates two learning modules to strengthen both spatial and temporal representations.

AU Relationship Modeling: AUs, as defined in the Facial Action Coding System (FACS), are physiologically interpretable units that encode facial muscle movements and exhibit cross-subject consistency. Therefore, they are widely used in micro-expression analysis and synthesis. Liu et al. [

33] manually defined 13 facial regions and used 3D filters to perform convolution over feature maps for AU localization. Inspired by this approach, we introduce a GCN to model co-occurrence relationships between AUs. Each AU is represented as a node in a graph, and the edge weights are defined based on empirical co-occurrence probabilities.

3. Framework and Methods

3.1. Overall System Architecture

The proposed framework introduces a closed-loop pipeline for micro-expression localization and animation synthesis in virtual humans, overcoming the limitations of conventional coarse-grained templates that neglect subtle dynamics and fail to integrate with 3D rendering engines.

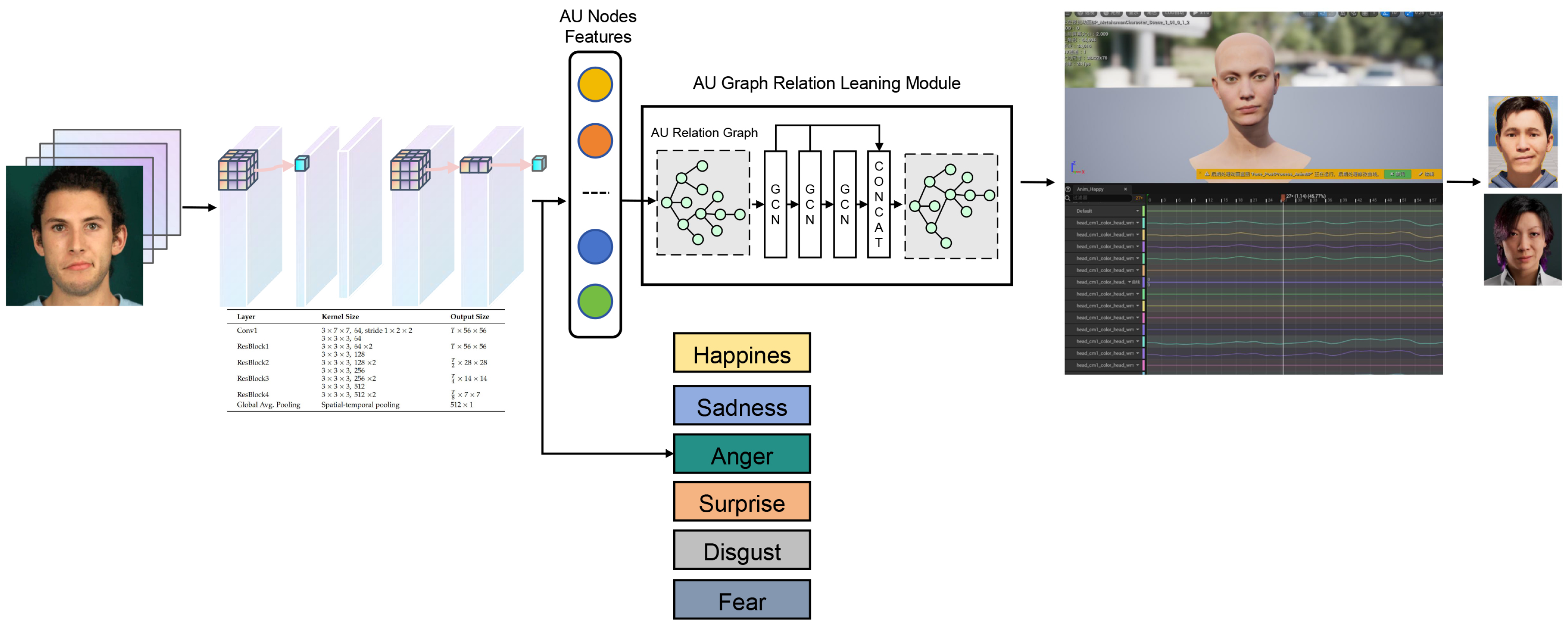

As illustrated in

Figure 1, a 3D-ResNet-18 backbone extracts spatiotemporal features from input sequences. These features drive dual regression branches to predict normalized onset and offset timestamps in [0, 1], optimized by MSE loss with a temporal order constraint for consistency. Meanwhile, AU features construct an asymmetric co-occurrence graph, processed via an AU-GCN-CUR module to capture inter-AU dependencies and produce structure-aware representations. End-to-end training combines losses for localization and AU embedding.

In inference, normalized timestamps are mapped to frame indices, while AU predictions generate continuous control curves for real-time facial actuation in Unreal Engine. This unified design enables precise synthesis across intensities, surpassing static templates in flexibility and fidelity.

On CASME II [

34], the framework achieves superior accuracy and F1-scores over baselines; subjective evaluations affirm improved clarity and authenticity.

3.2. Temporal Segmentation

To address challenges in micro-expression recognition, where subtle and brief facial dynamics elude single-frame capture, we employ a 3D convolutional neural network (3D-CNN) for unified spatiotemporal modeling of video sequences. A lightweight 3D-ResNet-18 architecture [

35] serves as the backbone, extracting features across spatial (

) and temporal (

T) dimensions via 3D kernels to enhance sensitivity to fine-grained variations. This prioritizes temporal dynamics over spatial-only approaches, as in MotionSC [

36], while integrating explicit AU relational modeling absent in the latter.

Input sequences are preprocessed to fixed length (e.g., 16 frames using temporal interpolation model, TIM) and processed with kernels at stride 1 to detect transient dynamics. Output is a 512-dimensional feature vector post global average pooling (GAP), retaining spatiotemporal action patterns.

Temporal segmentation appends two regression branches to predict normalized onset and offset timestamps in [0, 1]:

Optimization employs combined loss:

with

,

as classification labels,

,

as timestamps, and

, ensuring alignment with spontaneous cues and transitions between similar emotions.

Architecture details appear in

Table 1, illustrating progressive temporal downsampling for contextual capture.

AU features from

F form nodes in directed graph

, where

V denotes AU nodes (e.g., 19 in CASME II) initialized as one-hot vectors, and As illustrated in

Figure 2E edges via co-activation probabilities

, producing an asymmetric adjacency matrix. An emotional layer augments nodes (e.g., 7-D vector for categories) to distinguish states like subtle joy vs. polite surprise. Features refine via GCN propagation:

with loss

(

),

binary cross-entropy for multi-label AU classification,

cross-entropy for emotions. This graph method captures inter-AU dependencies, surpassing MotionSC’s temporal 3D convolutions.

3.3. AU Graph Modeling with Emotion Layers

To model co-activation patterns and asymmetries per emotion type,action units (AUs) are represented as nodes in a directed graph augmented with emotion-layer annotations. Following AU relation modeling in,AU features are extracted from the 3D ConvNet output.The graph is

, where

V comprises AU nodes (e.g., 19 in CASME II),each with a 512-dimensional spatiotemporal feature vector;

E uses co-occurrence conditional probabilities:

yielding an asymmetric adjacency matrix

,with

the co-occurrence count of AUs

i and

j, and

the total count of AU

j.

L adds a multi-label emotion vector (e.g.,7-dimensional) per node via classification.

Graph convolutions refine AU intensity predictions and differentiate states, using 2–3 layers:

where

,

is the degree matrix,

the weights, and

ReLU. A self-attention pooling layer [26] retains key nodes (ratio

) by scoring

Z, selecting top-

k, and updating features/matrix.

Loss integrates AU binary cross-entropy (

) and emotion cross-entropy (

):

with

, enabling distinction of subtle emotions like restrained fear vs. mild disgust.

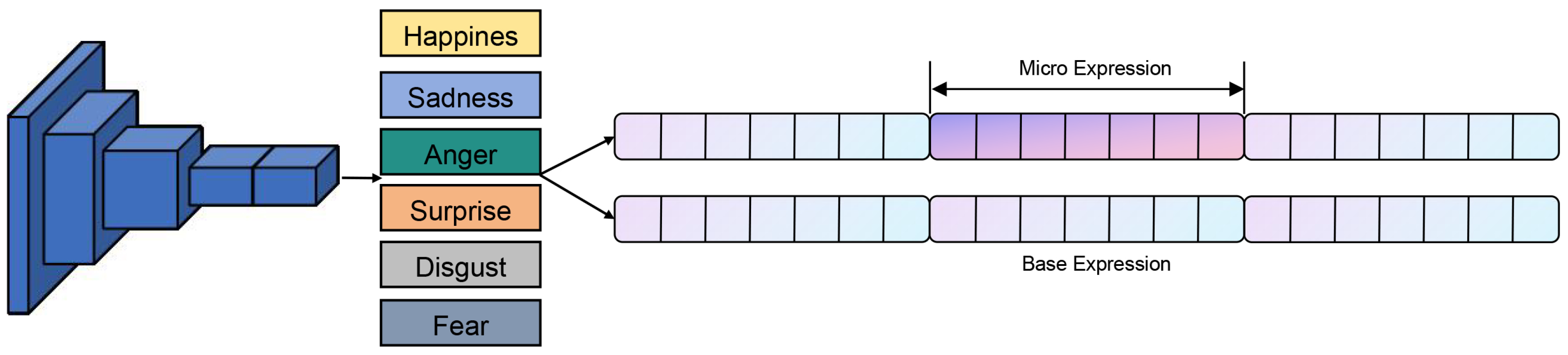

3.4. Animation Synthesis with Diverse Emotional Profiles

The predicted AU signals are transformed into smooth animation curves via cubic spline interpolation, modulated by emotion-specific intensity profiles,and mapped to rig controls in a commercial engine (e.g.,Unreal Engine [

37]) to drive lifelike digital human expressions.As illustrated in

Figure 3,This process not only captures micro-movements but also encodes differentiable emotional signatures, such as restrained fear or mild disgust.

For each AU signal sequence

, a continuous curve is generated using cubic B-spline interpolation:

where

are the B-spline basis functions, and

are control points derived from frame-by-frame AU activations and displacements, based on a predefined AU mapping scheme.

The curve is then modulated as:

where

is an emotion-specific modulator (e.g., high-amplitude for joy, low-amplitude for fear), and

represents intensity variation, sampled from user input or dataset distributions to preserve physiological realism in AU interrelations, as informed by AU-GACN’s intensity control.In Unreal Engine, the refined curves are dynamically generated using the Curve Editor API:

Invoke the FindRow method to match the input expression curve with entries in the AU dictionary and extract the corresponding RowValue (a time–displacement key-value pair).

Based on RowValue->Time and RowValue->Disp, create animation keyframes via FKeyHandle and append them to the animation curve.

Use SetKeyTangentMode to set the tangent mode to automatic (RCTMAuto), and call SetKeyInterpMode to set the interpolation mode to cubic (RCIMCubic), improving transition quality between keyframes.

The final curve is saved into the Unreal Engine project, ensuring consistency between the generated expressions and the imported animation data.This enables precise control and real-time preview of facial animation.

4. Validationk

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed micro-expression recognition and generation system, a dual-validation framework is adopted, encompassing both objective metrics and subjective user experience.

On the objective side, we assess the temporal prediction accuracy and overall model performance through cross-validation experiments. On the subjective side, user feedback is collected via questionnaire-based evaluations, in which participants rate the generated virtual human animations across three perceptual dimensions: clarity, naturalness, and authenticity.

4.1. System Performance Evaluation

4.1.1. Dataset and Experimental Settings

We propose a pipeline that processes facial videos to generate emotion-differentiated micro-expression animations for 3D digital humans. The framework comprises three core stages: temporal segmentation of micro-expressions, emotion-labeled AU relationship modeling, and real-time animation curve mapping with variable emotion intensities.

Temporal segmentation employs a 3D ConvNet to detect onset and offset frames of micro-expressions. Extracted AUs are then represented as nodes in a directed graph augmented with emotion labels, capturing co-activation patterns and asymmetries. A graph convolution module propagates contextual information to refine AU intensity predictions and differentiate emotional states (e.g., subtle joy versus polite surprise).

Predicted AU signals are interpolated via splines into smooth animation curves, modulated by emotion-specific intensity parameters to drive skeletal controls in commercial engines. The end-to-end design enables real-time performance (30-60 FPS in experiments, hardware-dependent).

4.1.2. Implementation Details

In this study, we adopt an 18-layer 3D-ResNet (ResNet3D-18) as the backbone network for spatiotemporal feature extraction from micro-expression sequences. Given the limited number of training samples, we employ sample-level updates in each training iteration, using a single video sequence as input to enhance adaptability to small-sample scenarios.

As shown in

Table 1, the model consists of four residual blocks. The input sequence has a temporal length of

T, and each frame is resized to a spatial resolution of

and normalized. This preprocessing is consistently applied to all training and validation data. In the 3D convolutional layers, the network contains five residual modules, each responsible for progressively extracting coarse-to-fine spatiotemporal features. Each residual block comprises two 3D convolutional layers with kernel sizes of

, followed by ReLU activation and batch normalization. Global average pooling is used to downsample the output feature map to a size of

, with spatial stride control while keeping the temporal dimension intact.

The GCN is configured with two stacked layers. The input is a one-hot encoding of 12 AU nodes, resulting in an initial feature matrix of size , where d is the feature dimension. The adjacency matrix A is constructed in a data-driven manner, with each element defined as the conditional probability . The output dimensions of the two GCN layers are set to 1,024 and 512, respectively.

For model validation, we adopt two cross-validation strategies: Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) and

k-fold cross-validation. In LOSO, the data from one randomly selected subject are held out for validation during each training iteration to minimize subject-specific bias. In

k-fold validation, the dataset is divided into

k subsets, with one subset used for validation and the remaining for training in each fold. Both strategies help to prevent the model from overfitting to specific data partitions and enhance generalization.

Table 2.

Comparison of Accuracy (%) Using k-fold and LOSO Evaluation.

Table 2.

Comparison of Accuracy (%) Using k-fold and LOSO Evaluation.

| Model |

k-fold Acc. (%) |

LOSO Acc. (%) |

| 3D-CNN (pre-trained) |

55.37 |

42.64 |

| 3D-CNN |

57.05 |

45.03 |

| AU_GCN_CUR |

64.11 |

45.71 |

In the k-fold cross-validation setting, the 3D-CNN model achieved an accuracy of 57.05%, showing a slight improvement over the pre-trained model, which attained 55.37%. This suggests that, under training strategies with moderate data volume and relatively balanced sample distribution, features learned from scratch are better suited to capture the subtle variations in micro-expressions.

In the LOSO validation setting, the 3D-CNN model also outperformed the pre-trained counterpart, achieving 45.03% versus 42.64%. These results indicate that pre-trained models face challenges in transferring to the micro-expression domain due to semantic domain discrepancies. Specifically, high-level features learned from large-scale action recognition datasets do not fully generalize to the fine-grained facial muscle deformations characteristic of micro-expressions.

The performance gains observed with the 3D-CNN model suggest that, when further combined with the GCN module, the system can effectively learn the intricate relationships between facial muscle activations and various micro-expression categories. This leads to a deeper and more accurate understanding of subtle facial behaviors.

As shown in

Table 3, among several micro-expression recognition models, the proposed

AU_GCN_CUR demonstrates the best overall performance. On the CASME II dataset, it achieves an accuracy of 64.11% and an F1-score of 42.93%, significantly outperforming traditional handcrafted feature-based methods (e.g., LBP-TOP [

7], MDMD [

38]) as well as most deep learning approaches (e.g., CNN+LSTM [

39], CapsuleNet [

40], MER-GCN [

41]).

Among these methods, LBP-TOP—recognized as one of the stronger handcrafted baselines—yields an F1-score of 42.4%, which is slightly lower than that of our model. While the CNN+LSTM model achieves a relatively high accuracy of 60.98%, its F1-score remains inferior to that of AU_GCN_CUR, indicating less balanced classification performance.

Overall, the results confirm that AU_GCN_CUR not only delivers superior classification accuracy but also excels in terms of balanced performance as reflected by the F1-score. This makes it an effective and robust solution for micro-expression recognition tasks.

4.2. User Subjective Perception Study

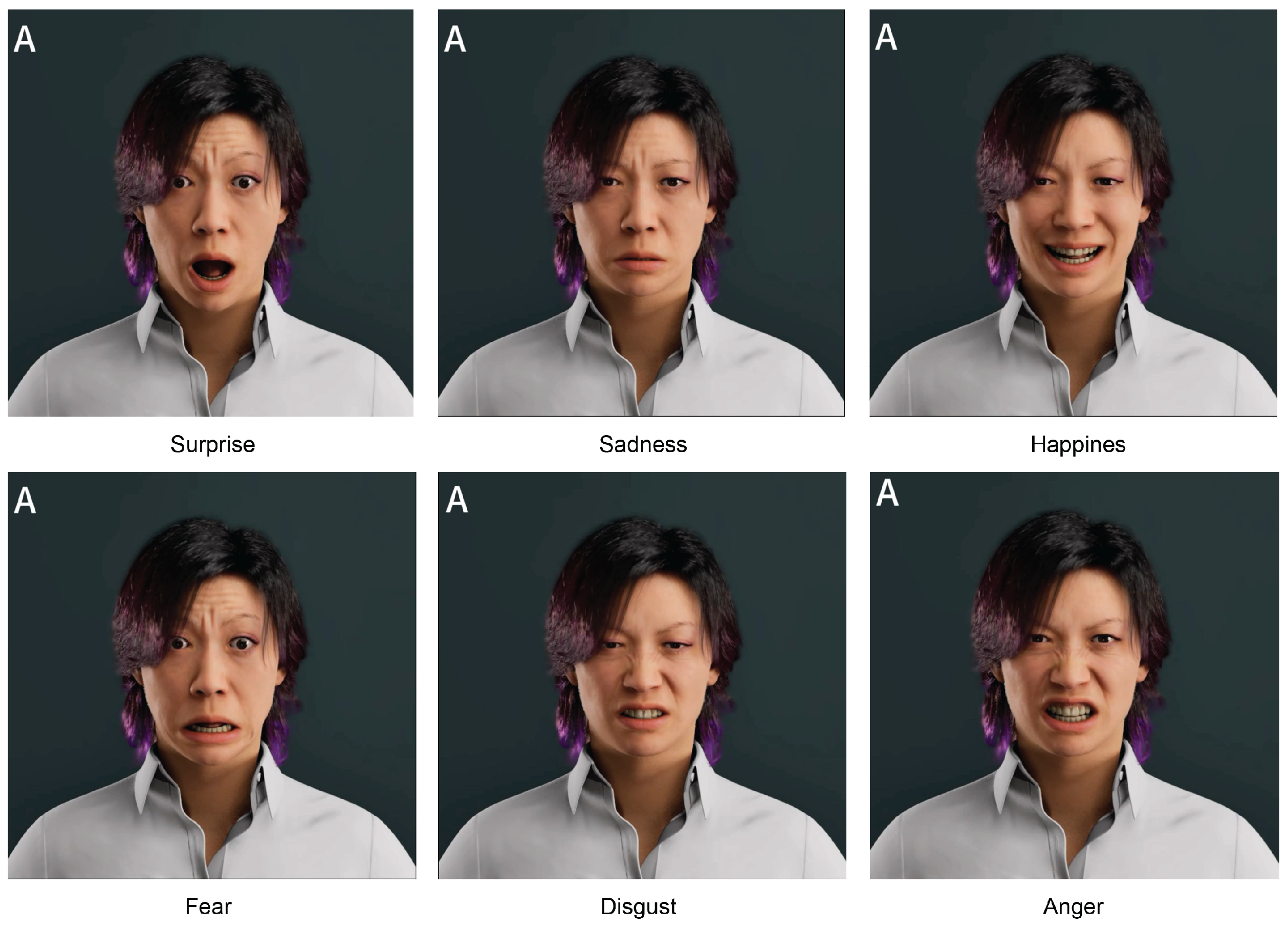

To further evaluate the practical impact of micro-expressions on emotional expressiveness in virtual humans, we designed a user perception experiment combining visual stimuli and subjective questionnaires.

The experiment employed system-generated 3D virtual human animation videos as stimulus materials, covering the six basic emotion categories proposed by Ekman: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. Two types of videos were used: Video A presented basic emotional expressions without micro-expressions, while Video B included micro-expressions integrated into the same basic emotional expressions.

4.2.1. Participant Demographics

A total of 82 participants were recruited for the experiment, including 37 males (45.1%) and 45 females (54.9%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to over 51 years, with the majority (50.0%) falling within the 25–30 age group. In terms of educational background, over 90% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 39.0% possessed a master’s degree or above.

All participants provided informed consent prior to the experiment, acknowledging that their data would be anonymized and used solely for academic research purposes. The entire experimental procedure was approved by an institutional ethics committee to ensure compliance with ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

4.2.2. Experimental Hypothesis and Questionnaire Design

The proposed null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference between Video A and Video B in terms of emotional clarity, naturalness, and authenticity.

For each pair of A/B videos within a given emotion category, participants were asked to independently rate the two videos across the three dimensions using a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 indicates “very low” and 5 indicates “very high”). This design allows us to quantitatively assess the impact of micro-expressions on user perception.

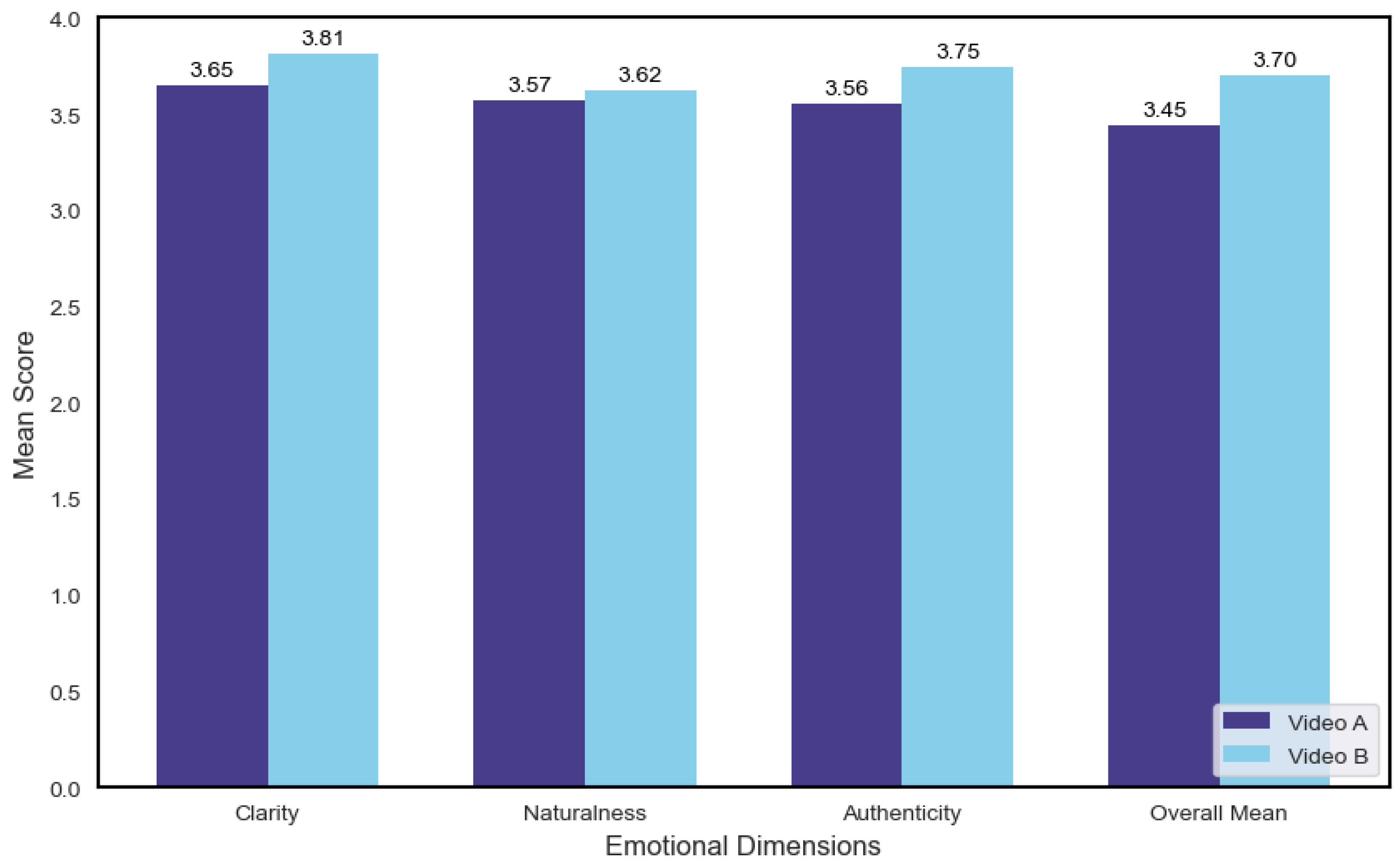

4.3. Data Analysis

A Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine the overall effect of video type (A vs. B) on the three subjective rating dimensions. The results indicated that individual differences in

clarity (

),

naturalness (

), and

authenticity (

) did not reach statistical significance. However, the overall mean score (

All_Mean) for Video B was significantly higher than that for Video A (

), as shown in

Figure 4.

These findings suggest that the inclusion of micro-expressions in virtual human animations leads to higher overall user approval, even if differences in individual perceptual dimensions are not independently significant.

To further investigate the effect of micro-expressions on specific emotions, separate MANOVA tests were conducted for each of the six basic emotions. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

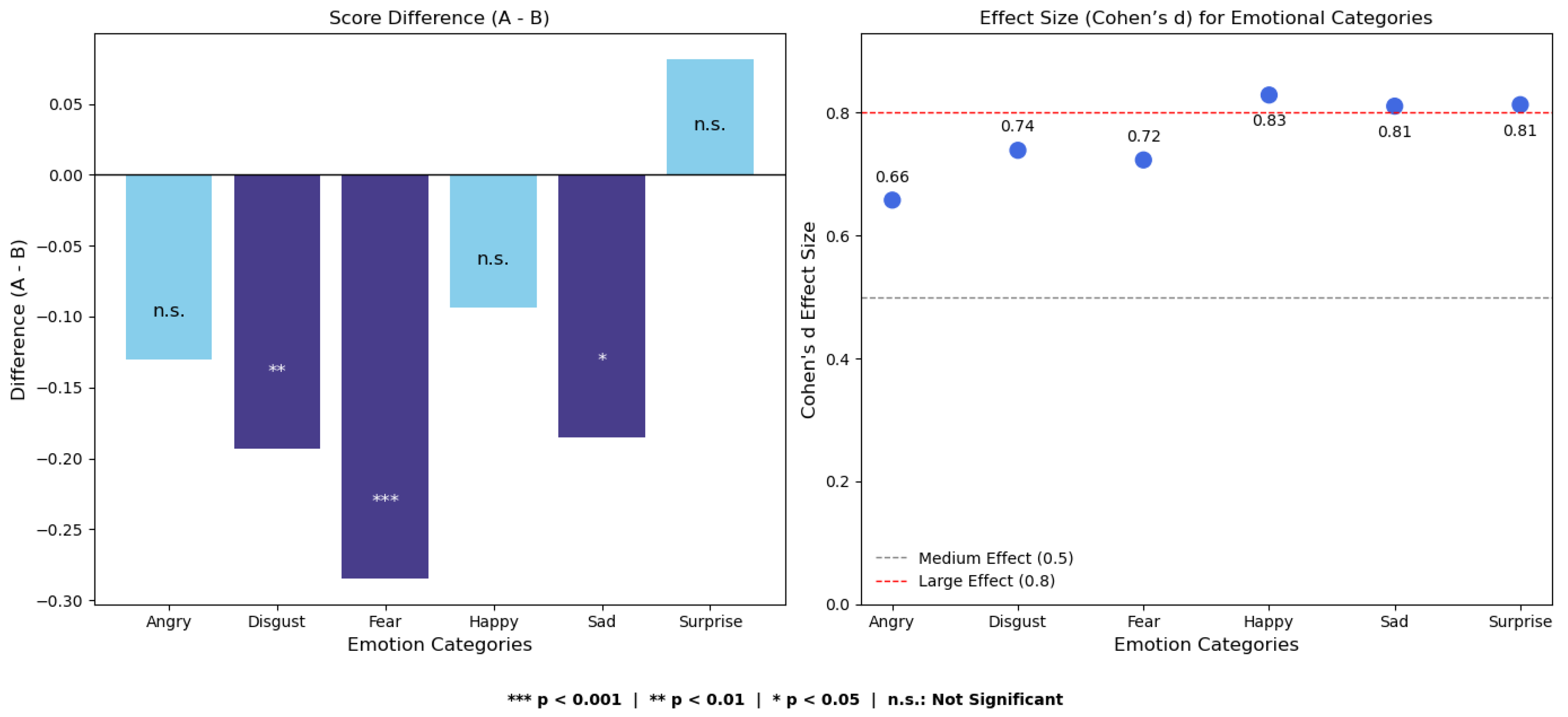

As shown, the emotion category fear received significantly higher ratings in Video B compared to Video A (), while disgust approached the threshold of significance (). Other emotions, such as happiness and surprise, did not exhibit notable differences between the two video types.

As shown in

Table 5, paired-sample

t-tests were conducted for each of the six basic emotions. The results revealed significant increases in perceived scores for

fear (

) and

disgust (

) in Video B, while

sadness approached marginal significance (

). According to the Bonferroni correction threshold (

), only the first two effects can be considered statistically robust. The visual results in

Figure 5 further emphasize that

fear and

disgust were the two emotions with the most notable improvement in perceived expression quality in Video B.

Effect size analysis using Cohen’s

d revealed values ranging from 0.658 to 0.829, indicating medium to large effects. According to Cohen’s criteria [

47],

is considered a small effect,

a medium effect, and

or above a large effect. The value

observed in our study falls within the medium range; however, in the context of micro-expression recognition—where perceptual signals are subtle and subjective noise is high—such an effect size is considered practically meaningful. In particular, even slight improvements in clarity or authenticity may significantly impact user experience and emotional understanding in real-world human–computer interaction scenarios.

To assess the consistency of participants’ subjective evaluations, additional paired-sample

t-tests were conducted on the three perceptual dimensions:

clarity,

naturalness, and

authenticity. The results are presented in

Table 6.

Significant improvements were observed in both clarity () and authenticity () following the inclusion of micro-expressions, while no significant difference was found for naturalness ().

It is worth noting that although Video B received slightly higher ratings than Video A in the naturalness dimension, the difference did not reach statistical significance (). This outcome may be attributed to the inherently short duration and subtle intensity of micro-expressions, which may not be sufficient to noticeably influence the overall smoothness and coordination of facial movements.

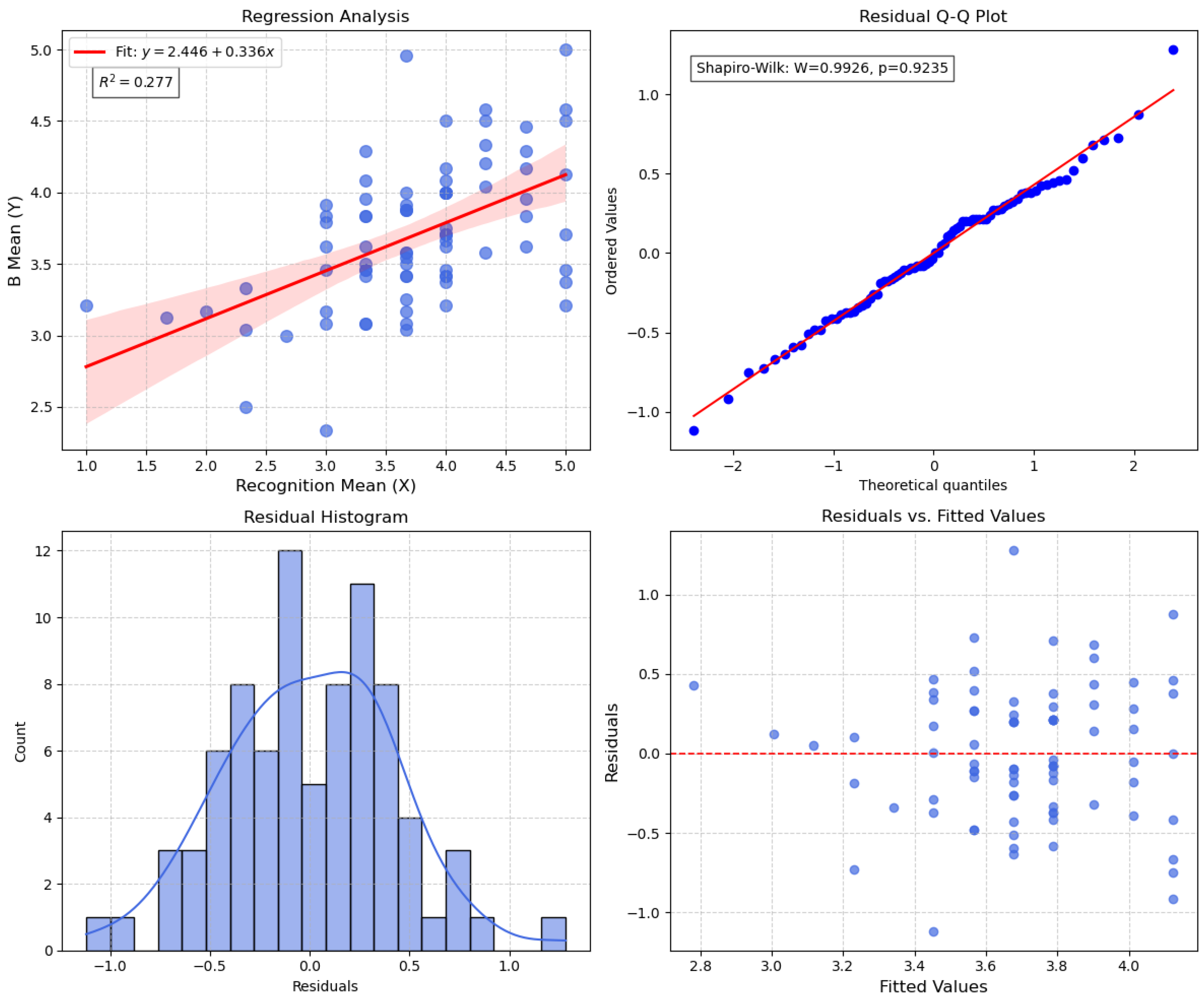

Finally, a regression analysis was conducted to further examine the predictive effect of “virtual human recognition score” on the emotional expression ratings of Video B. As shown in

Figure 6, the results indicate a significant positive correlation between the two variables (

,

), satisfying key regression assumptions including normality and independence of residuals.

Detailed regression parameters are reported in

Table 7.

4.4. Questionnaire Analysis Results

Based on the experimental data and statistical analyses, the following key findings can be summarized:

In terms of overall perceptual ratings, Video B was rated significantly higher than Video A, indicating that the inclusion of micro-expressions had a positive impact on the overall user experience.

In the analysis of the six basic emotions, Video B showed significantly higher ratings for fear (, ) and disgust (, ), both of which met the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (). This suggests that micro-expressions notably enhanced the expressiveness and perceptual salience of specific negative emotions in virtual humans.

In the paired-sample t-tests, Video B also received significantly higher ratings than Video A in the dimensions of clarity (, ) and authenticity (, ), indicating that micro-expressions improved both the detail and credibility of facial expressions.

Regression analysis further revealed that participants’ recognition scores of the virtual human significantly predicted their ratings of emotional expressiveness (, ). The regression model met the assumptions of residual normality and independence, indicating a strong positive correlation between recognition clarity and emotion perception.

In summary, the inclusion of micro-expressions not only enhanced the perceived realism and recognizability of emotional expressions—particularly in high-discrimination categories such as fear and disgust—but also underscored the importance of high-fidelity emotional expression in virtual human interaction.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposes an integrated framework for micro-expression recognition and 3D animation generation in virtual human systems, constructing a closed-loop pipeline that encompasses recognition, extraction, reconstruction, and animation driving. Spatiotemporal joint modeling is achieved through 3D-ResNet-18, while a co-occurrence-based graph convolutional network (GCN) captures structural dependencies among facial action units (AUs), enhancing the accuracy of micro-expression temporal localization and semantic representation consistency. The recognition results are mapped to animation curves, driving facial expressions in virtual humans to achieve fine-grained, realistic emotional dynamics rendering in 3D space.

Objective evaluations demonstrate that the proposed AU_GCN_CUR model outperforms multiple baselines on the CASME II dataset, achieving an F1 score of 42.93%, confirming its effectiveness and robustness in micro-expression recognition tasks. Subjective experiments indicate that incorporating micro-expressions significantly improves user ratings for clarity and authenticity, particularly for negative emotions such as fear and disgust, with notable enhancements in discriminability and emotional conveyance performance.

In summary, this study bridges micro-expression recognition and animation control, providing a structured and controllable solution for high-fidelity emotional modeling in virtual humans. Future work will integrate Transformer decoders and diffusion generative models to explore efficient and realistic micro-expression strategies, and incorporate Unity or Unreal Engine to enhance the naturalness and credibility of emotional human-machine interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F., F.Y.and Y.L.; methodology, L.F, F.Y. and J.Z.; software, L.F.and F.Y.; validation, L.F. and F.Y.; formal analysis, L.F.and F.Y.; investigation, L.F., F.Y. and J.Z.; resources, Y.L., M.W.; data curation, L.F. and F.Y.; writing original draft preparation, L.F.and F.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.F. and F.Y.; visualization, L.F. and F.Y.; supervision, Y.L., M.W.and J.Z.; project administration, Y.L., M.W.; funding acquisition, Y.L., M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology, "100 Foreign Experts Plan of Hebei province", in 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Queiroz, R.; Musse, S.; Badler, N. Investigating Macroexpressions and Microexpressions in Computer Graphics Animated Faces. https://doi.org/10.1162/PRES_a_00180. PRESENCE: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 2014, 23: 191–208. [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Adamo, N.; Villani, N.J. Micro-expressions in Animated Agents. https://doi.org/10.54941/ahfe1001081. Intelligent Human Systems Integration (IHSI 2022), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hong, X.; Moilanen, A.; Huang, X.; Pfister, T.; Zhao, G.; Pietikäinen, M. Reading Hidden Emotions: Spontaneous Micro-expression Spotting and Recognition. https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.00423. arXiv, 2015, abs/1511.00423. arXiv:1511.00423.

- Ren, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. Electroencephalography (EEG)-Based Comfort Evaluation of Free-Form and Regular-Form Landscapes in Virtual Reality. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14020933. Applied Sciences, 2024, 14(2): 933. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L. Novel Insights into Rural Spatial Design: A Bio-Behavioral Study Employing Eye-Tracking and Electrocardiography Measures. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0322301. PLoS ONE, 2025, 20(5): e0322301. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.J.; Wu, Q.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.H.; Fu, X. How Fast Are the Leaked Facial Expressions: The Duration of Micro-Expressions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 2013, 37, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, G. LBP-TOP: A Tensor Unfolding Revisit. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ACCV 2016 Workshops; Chen, C.S.; Lu, J.; Ma, K.K., Eds., Cham, 2017; pp. 513–527.

- Chaudhry, R.; Ravichandran, A.; Hager, G.; Vidal, R. Histograms of Oriented Optical Flow and Binet-Cauchy Kernels on Nonlinear Dynamical Systems for the Recognition of Human Actions. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009; pp. 1932–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, B.K.P.; Schunck, B.G. Determining Optical Flow 1980.

- Koenderink, J.J. Optic Flow. Vision Research 1986, 26, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.J.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Fu, X. CASME II: An Improved Spontaneous Micro-Expression Database and the Baseline Evaluation. PLOS ONE January 27, 2014, 9, e86041. [CrossRef]

- Khor, H.Q.; See, J.; Phan, R.C.W.; Lin, W. Enriched Long-Term Recurrent Convolutional Network for Facial Micro-Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), 2018, pp. 667–674.

- Qingqing, W. Micro-Expression Recognition Method Based on CNN-LSTM Hybrid Network. International Journal of Wireless and Mobile Computing 2022, 23, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Shen, J. Real-Time and Light-Weighted Unsupervised Video Object Segmentation Network. Pattern Recognition 2021, 120, 108120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, R. STA-GCN: Spatio-Temporal AU Graph Convolution Network for Facial Micro-Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision; Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, F.; Tan, T.; Wang, Y.; Lai, J.; Zhao, Y., Eds., Cham, 2021; pp. 80–91.

- Lo, L.; Xie, H.X.; Shuai, H.H.; Cheng, W.H. MER-GCN: Micro-Expression Recognition Based on Relation Modeling with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval (MIPR); 2020; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- A New Neuro-Optimal Nonlinear Tracking Control Method via Integral Reinforcement Learning with Applications to Nuclear Systems. Neurocomputing 2022, 483, 361–369. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Li, J.; Wang, S.J.; Duan, X.H.; Yan, W.J.; Xie, H.Y.; Huang, S.C. Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Macro- and Micro-Expression Spotting in Long Video Sequences. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2020); 2020; pp. 734–741. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, C.H.; Yap, M.H.; Davison, A.; Kendrick, C.; Li, J.; Wang, S.J.; Cunningham, R. 3D-CNN for Facial Micro- and Macro-Expression Spotting on Long Video Sequences Using Temporal Oriented Reference Frame. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2022; MM ’22, pp. 7016–7020.

- Lin, T.; Zhao, X.; Su, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, M. BSN: Boundary Sensitive Network for Temporal Action Proposal Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19.

- EKMAN, P. Facial Action Coding System (FACS). A Human Face 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama, Y.; Bhardwaj, A.; Zhao, R.; Romeo, O.; Akoju, S.; Cassell, J. Socially-Aware Animated Intelligent Personal Assistant Agent. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, Los Angeles, 2016; pp. 224–227.

- Marsella, S.; Gratch, J. University of Southern California.

- Coface: Global Credit Insurance Solutions To Protect Your Business. https://www.coface.com/, 2025.

- Wang, S.J.; Li, B.J.; Liu, Y.J.; Yan, W.J.; Ou, X.; Huang, X.; Xu, F.; Fu, X. Micro-Expression Recognition with Small Sample Size by Transferring Long-Term Convolutional Neural Network. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learning Spatiotemporal Features with 3D Convolutional Networks. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300408292_Learning_Spatiotemporal_Features_with_3D_Convolutional_Networks.

- Tran, D.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R.; Torresani, L.; Paluri, M. Learning Spatiotemporal Features with 3D Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile; 2015; pp. 4489–4497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, M.; Bai, S.; Huang, T.; Bai, X. Asymmetric Non-Local Neural Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019; pp. 593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Lin, Z.; Shen, X.; Brandt, J.; Hua, G. A Convolutional Neural Network Cascade for Face Detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015; pp. 5325–5334. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo Vadis, Action Recognition? A New Model and the Kinetics Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 4724–4733. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, P.; Brox, T. Object Segmentation in Video: A Hierarchical Variational Approach for Turning Point Trajectories into Dense Regions. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision; 2011; pp. 1583–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Qu, S.; Xi, Y.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Wan, S. Image Caption Generation with High-Level Image Features. Pattern Recognition Letters 2019, 123, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Zong, Y. SMA-STN: Segmented Movement-Attending Spatiotemporal Network forMicro-Expression Recognition, 2020, [arXiv:cs/2010.09342].

- Yan, W.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Fu, X. CASME II: An improved spontaneous micro-expression database and the baseline evaluation, 2014.

- Liu, W.; Luo, W.; Lian, D.; Gao, S. Future Frame Prediction for Anomaly Detection - A New Baseline. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018; pp. 6536–6545. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Song, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Capodieci, A.; Jayakumar, P.; Barton, K.; Ghaffari, M. MotionSC: Data Set and Network for Real-Time Semantic Mapping in Dynamic Environments, 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.07060. [CrossRef]

- Epic Games. FRichCurve API Reference - Unreal Engine 5.0 Documentation. https://dev.epicgames.com/documentation/en-us/unreal-engine/API/Runtime/Engine/Curves/FRichCurve?application_version=5.0.

- Wang, F.; Ainouz, S.; Lian, C.; Bensrhair, A. Multimodality Semantic Segmentation Based on Polarization and Color Images. Neurocomputing 2017, 253, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. Video-Based Emotion Recognition Using CNN-RNN and C3D Hybrid Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2016; ICMI ’16, pp. 445–450.

- Quang, N.V.; Chun, J.; Tokuyama, T. CapsuleNet for Micro-Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019), 2019, pp. 1–7.

- Mei, L.; Lai, J.; Feng, Z.; Xie, X. Open-World Group Retrieval with Ambiguity Removal: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2021; pp. 584–591. [Google Scholar]

- Yuhong, H. Research on Micro-Expression Spotting Method Based on Optical Flow Features. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2021; MM ’21, pp. 4803–4807.

- Cohn, J.; Zlochower, A.; Lien, J.; Kanade, T. Feature-Point Tracking by Optical Flow Discriminates Subtle Differences in Facial Expression. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Third IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition; 1998; pp. 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zha, Q.; Wu, H. Soften the Mask: Adaptive Temporal Soft Mask for Efficient Dynamic Facial Expression Recognition, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2502.21004].

- Yang, B.; Wu, J.; Ikeda, K.; Hattori, G.; Sugano, M.; Iwasawa, Y.; Matsuo, Y. Deep Learning Pipeline for Spotting Macro- and Micro-Expressions in Long Video Sequences Based on Action Units and Optical Flow. Pattern Recognition Letters 2023, 165, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.W.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.J. LSSNet: A Two-Stream Convolutional Neural Network for Spotting Macro- and Micro-Expression in Long Videos. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2021; MM ’21, pp. 4745–4749.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2 ed.; Routledge: New York, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).