1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Mucormycosis is a life-threatening angio-invasive fungal infection caused by organisms within the Mucorales order (formerly classified under Zygomycetes), ranking as the third most common invasive fungal infection globally, following candidiasis and aspergillosis [

1,

2,

3]. The Mucorales order encompasses 55 genera and 260 species, of which approximately 40 are recognized as clinically significant human pathogens [

4,

5].

India reports the highest global incidence (140 cases per million population), while population-based studies in the U.S. estimate an annual incidence of 1.7 cases per million (~500 cases/year) [

6]. In Mexico, a retrospective analysis (1982–2016) identified 418 mucormycosis cases, with 72% occurring in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and Rhizopus spp. as the predominant isolate [

7]. Pediatric data from 2011 highlight pulmonary fungal infections in 100 children, with mucormycosis accounting for 6% of cases, compared to aspergillosis (54%), pneumocystosis (26%), and histoplasmosis (7%) [

8].

Mucorales thrive in environments with iron overload, acidic pH, and immunosuppression, rapidly proliferating via resilient zygospores. Their hallmark histopathological feature is broad, ribbon-like, pauciseptate hyphae capable of angio-invasion, leading to tissue necrosis [

9,

10,

11]. Transmission occurs via spore inhalation (respiratory tract), ingestion (gastrointestinal), or traumatic inoculation (cutaneous). Immunocompromised individuals are disproportionately affected, with common clinical presentations including rhinocerebral (55%) and pulmonary (30%) involvement. Pulmonary mucormycosis often mimics chronic pneumonia but may progress to severe complications such as bronchopleural fistula (BPF), abscesses, or chronic cavitary lesions [

12].

We present a case report of a 32-year-old female with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes presented to our institution with progressive dyspnea, productive cough, and chills. Imaging revealed left lower lobe consolidation with cavitation. Despite empiric antibiotics, clinical deterioration prompted surgical intervention. Thoracotomy with wedge resection and histopathological biopsy confirmed pulmonary mucormycosis, demonstrating invasive, non-septate hyphae. Postoperative treatment with liposomal amphotericin B and glycemic optimization led to gradual recovery, underscoring the critical role of early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management.

2. Case Presentation

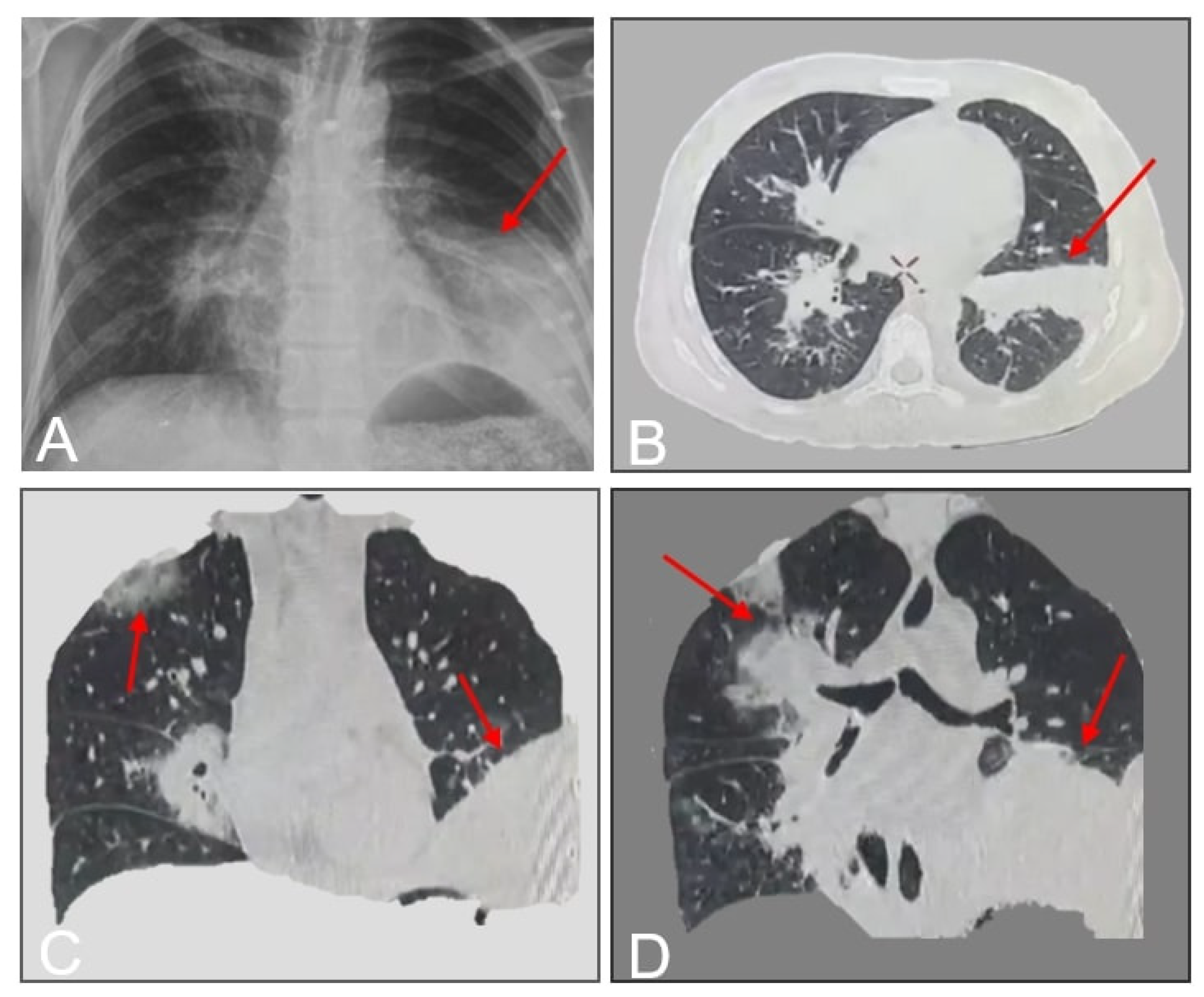

A 33-year-old female with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and hypothyroidism presented with a 10-day history of fever, dry cough, pleuritic chest pain, and progressive dyspnea. Initial outpatient management with oral antibiotics (unspecified) failed to alleviate symptoms. On day 12 of symptom onset, she was hospitalized at a rural facility, where she developed hemoptysis and worsening respiratory distress. Laboratory studies confirmed diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and imaging suggested pneumonia. Due to clinical deterioration and lack of diagnostic resolution, she was transferred to our tertiary care center. On admission (day 12), the patient exhibited hypoxia (SpO2 89% on room air), tachypnea, and diminished breath sounds over the left hemithorax. Chest CT revealed left lower lobe consolidation with basal predominance (

Figure 1).

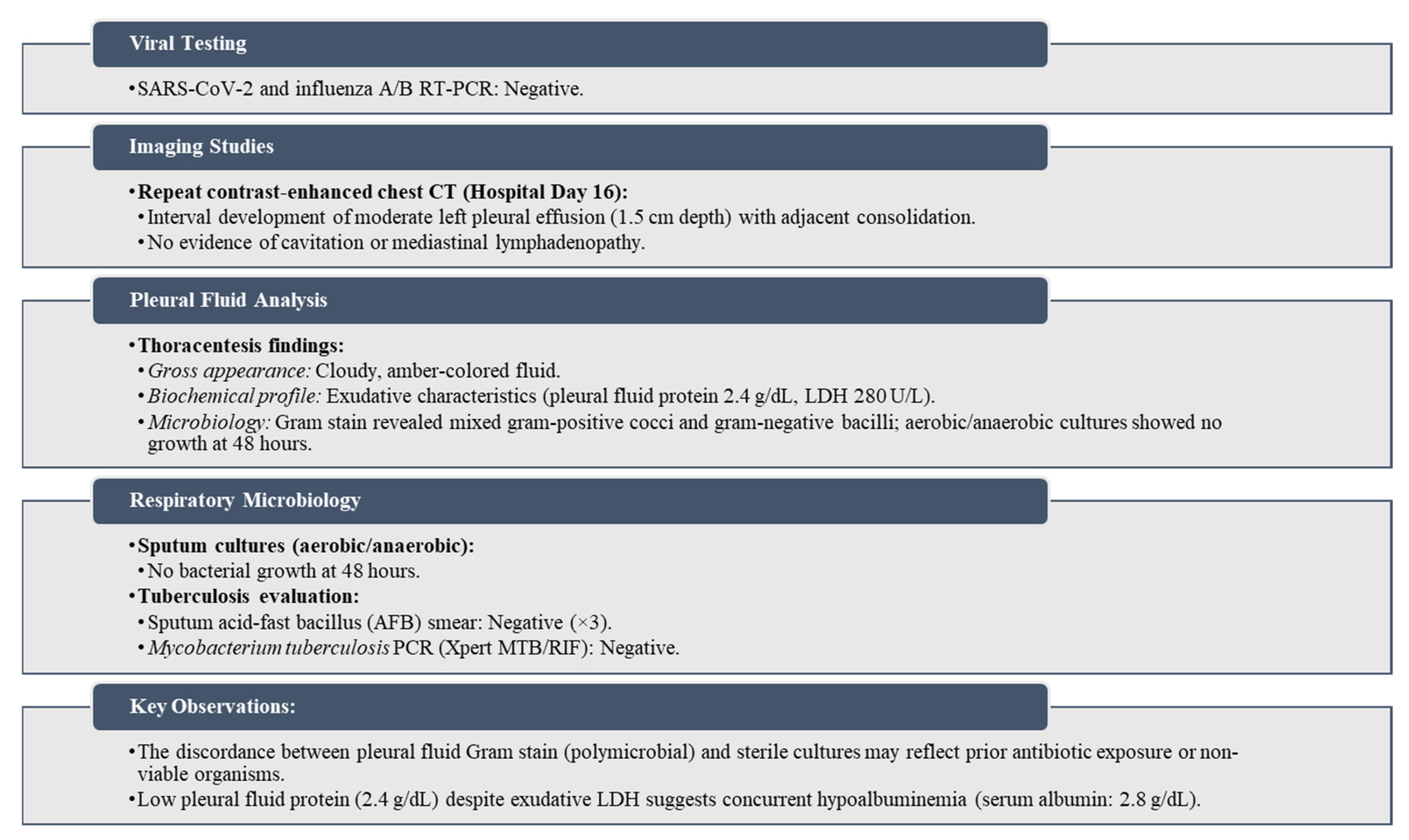

Arterial blood gas analysis showed respiratory alkalosis (pH 7.48, pCO2 28 mmHg). Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics (intravenous ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin), fluid resuscitation, and supplemental oxygen (2 L/min via nasal cannula) were initiated. Diagnostic workup is shown in (

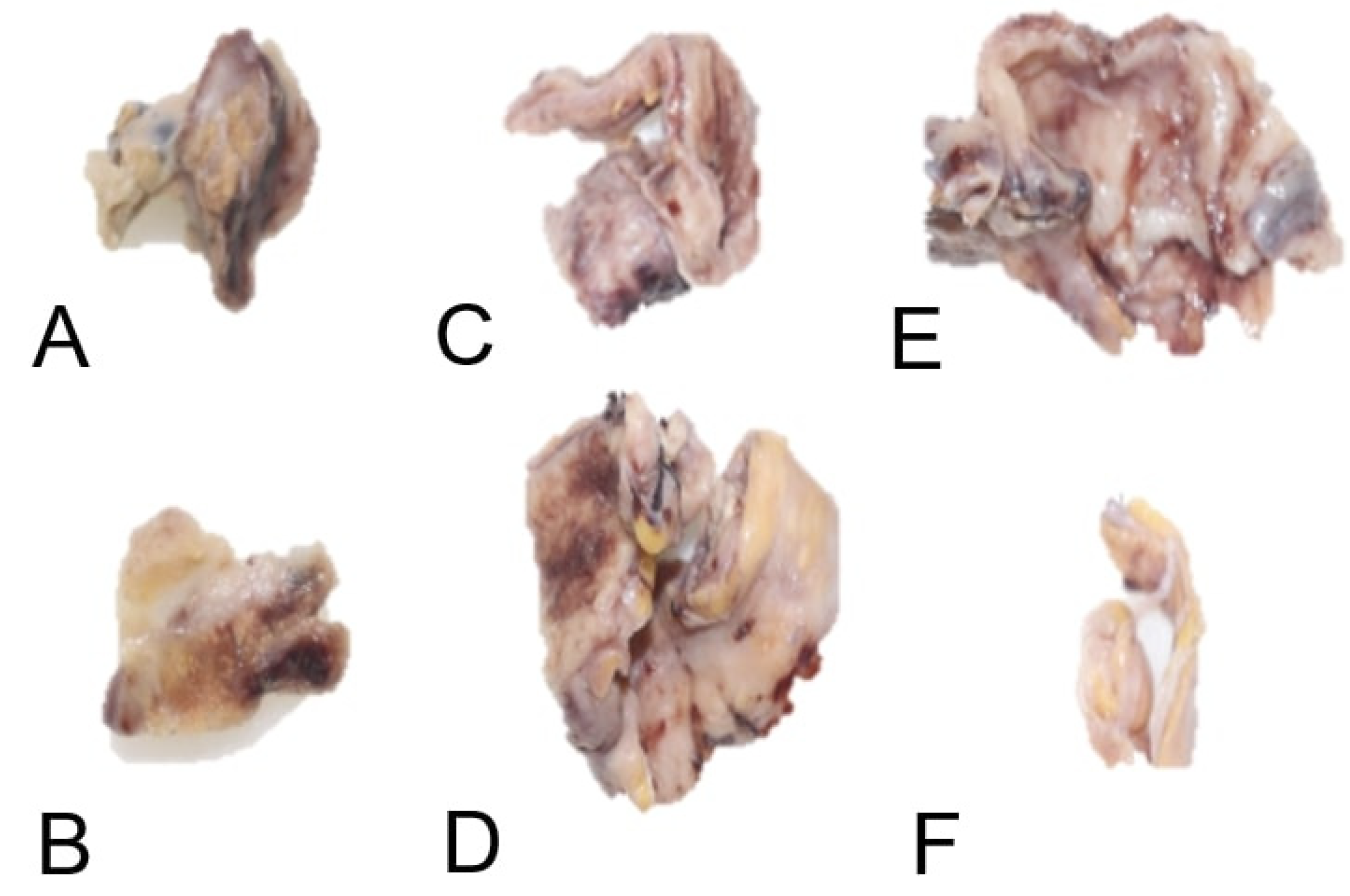

Figure 2). Persistent pleural effusion and clinical decline prompted thoracic surgery consultation. On day 20, the patient underwent left thoracotomy with decortication(

Figure 3), abscess drainage (segments X and VI), and repair of a bronchopleural fistula (

Figure 4).

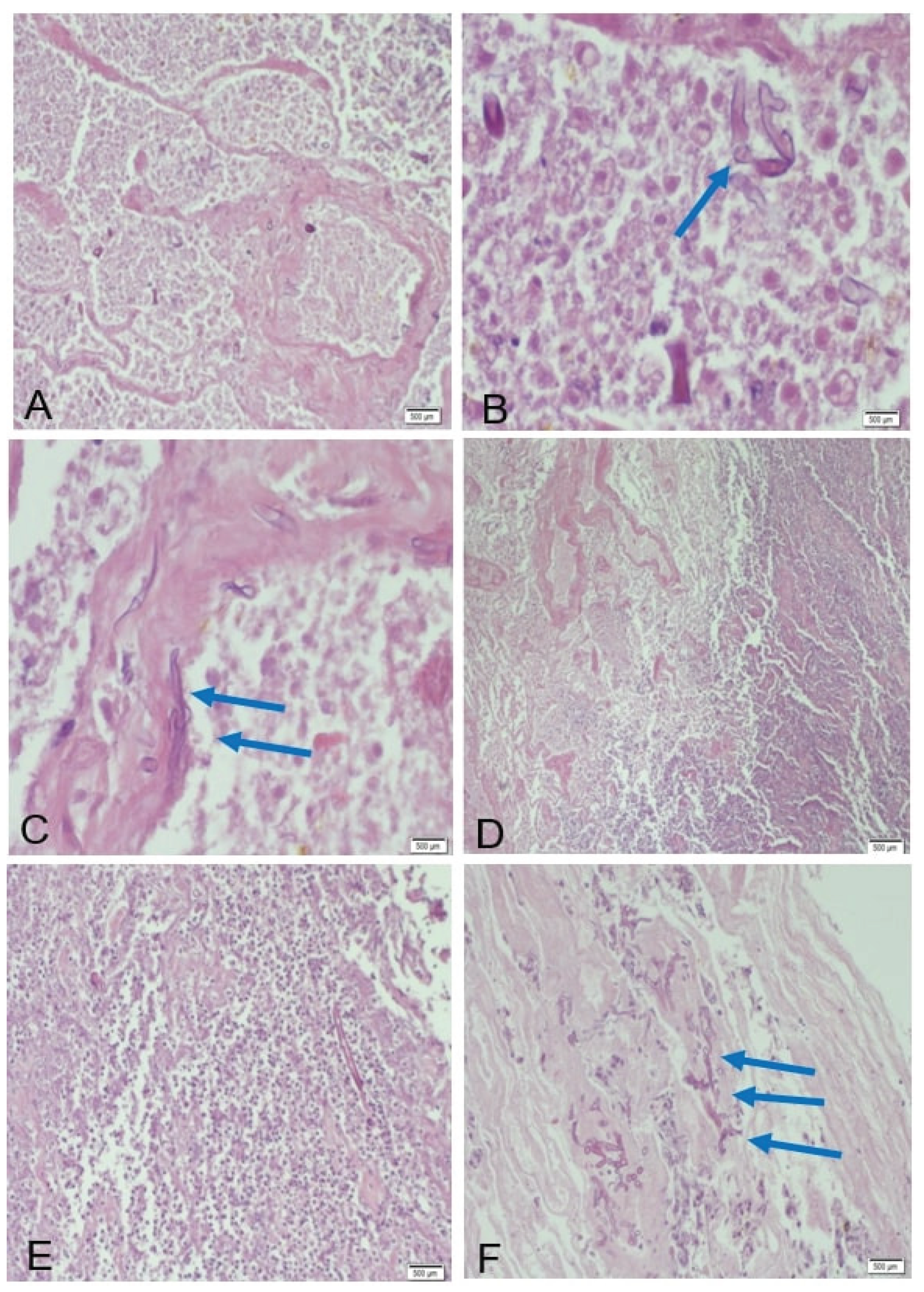

Postoperatively, respiratory mechanics improved transiently, but recrudescent dyspnea and productive cough on day 27 necessitated further evaluation. Histopathological analysis of the lung biopsy revealed the following key features: coagulative necrosis, extensive zones of ischemic necrosis accompanied by neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with tissue infarction secondary to angioinvasion. fungal morphology with broad (10–20 μm), ribbon-like, pauciseptate hyphae with irregular branching (90° angles), infiltrating vascular lumina and walls (

Figure 5), pathognomonic of Mucorales infection.

Reactive changes, fibrotic remodeling of the visceral pleura and pronounced capillary proliferation, indicative of chronic tissue repair mechanisms. Antifungal therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) and isavuconazole (372 mg loading dose followed by 186 mg daily) was initiated on day 28. After 14 days of inpatient treatment, the patient achieved clinical stability and was discharged on oral isavuconazole. Over six months, she experienced three readmissions for DKA exacerbations and recurrent dyspnea, highlighting challenges in long-term glycemic control and antifungal adherence.

3. Discussion

Mucormycosis predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with diabetes mellitus (DM)—especially with ketoacidosis, chronic renal disease, or diabetic foot—and patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy [

13]. Our case highlights a 33-year-old female with refractory hyperglycemia despite insulin therapy, underscoring the interplay between uncontrolled DM and fungal susceptibility. Infection typically occurs via inhalation of Mucorales spores from soil or decaying organic matter [

14,

15], with occupational exposure (e.g., farming, as in this patient’s corn/pumpkin harvesting) representing a documented environmental risk [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Diabetic patients exhibit impaired innate immunity, characterized by reduced IL-1 and TNF-α production, phagocytic dysfunction, and elevated tissue iron availability—factors that collectively promote spore germination and angioinvasion [

4,

8]. Notably, DM and solid organ transplantation are the leading risk factors for pulmonary and gastrointestinal mucormycosis [

11].

Our patient developed pulmonary mucormycosis complications—bronchopleural fistula (BPF) and abscess—within 10 days of referral, aligning with reported median BPF onset timelines (8–12 days) [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Initial nonspecific symptoms (progressive dyspnea, pleuritic pain) and antibiotic-refractory pneumonia prompted exclusion of bacterial/viral etiologies via negative sputum cultures, pleural fluid analysis, and SARS-CoV-2/influenza RT-PCR. Chest radiography revealed lobar consolidation and cavitation, consistent with prior studies (consolidation: 43%, cavitation: 30%) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Contrast-enhanced thoracic CT, the gold standard for assessing pulmonary mucormycosis (PM) [

5], demonstrated ground-glass opacities, bronchial thickening, and BPF-related features (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Classic findings such as the “halo sign” (nodule encircled by ground-glass opacity) and vascular thrombosis leading to pulmonary infarction [

3,

4,

5,

6] were absent, though disease extension into adjacent structures (e.g., pleura) was evident.

Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology demonstrating broad, pauci-septate hyphae invading vasculature, accompanied by coagulative necrosis and neutrophilic infiltrates [

6,

7,

8]. In this case, biopsy confirmed Mucorales hyphae within small pulmonary vessels and pleural tissue (

Figure 4). Differentiation from aspergillosis—marked by thin, acutely branching hyphae—was critical [

6]. Molecular speciation via RT-PCR targeting Mucorales 28S rRNA could not be performed due to institutional resource constraints.

Given progressive respiratory failure and BPF, surgical intervention (thoracotomy, abscess drainage, fistula repair) was prioritized to reduce fungal burden and restore pleural integrity [

10]. Adjunctive antifungal therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) and isavuconazole (372 mg loading dose followed by 186 mg/day) was initiated postoperatively, reflecting current evidence for combination therapy in severe cases [

15,

16]. Despite clinical improvement, three readmissions for recurrent DKA and dyspnea over six months highlighted challenges in glycemic control and antifungal adherence.

4. Conclusions

This case reinforces the lethality of mucormycosis in diabetics and the imperative for early suspicion in antibiotic-refractory pneumonia. While CT and histopathology remain diagnostic cornerstones, resource limitations often delay confirmation. Multimodal management—surgical debridement, amphotericin-based therapy, and glycemic optimization—is critical to mitigate mortality (>50% in pulmonary cases). Future studies should address optimal antifungal duration and standardized protocols for BPF management.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, N.A.R.M. and N.I.L.; methodology, A.C.C.; validation, A.T.Z., L.F.G.C.; investigation, N.A.R.M.; resources, A.T.Z. and L.F.G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.R.M.; writing—review and editing, N.A.R.M.; visualization, A.C.C.; supervision, A.T.Z., L.F.G.C.; project administration, N.A.R.M.; funding acquisition, A.T.Z., L.F.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki”

Informed Consent Statement

“Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper”

Acknowledgments

“The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DKA |

Diabetes ketoacidosis |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| BPF |

Bronchopulmonary fistulae |

References

- Steinbrink, J.M.; Miceli, M.H. Mucormycosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2021, 35, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, M.T.; Salavert, M. Mucormicosis: perspectiva de manejo actual y de futuro. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2021, 38, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, U.; Maurer, E.; Lass-Flörl, C. Mucormycosis—from the pathogens to the disease. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, P.; Dunne, R.; Colson, Y.L.; Gill, R.R. Bronchopleural fistula and the role of contemporary imaging. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 148, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Hoffmann, K.; de Hoog, G.S.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L.; Voigt, K.; Bibashi, E.; et al. Species Recognition and Clinical Relevance of the Zygomycetous Genus Lichtheimia (syn. Absidia Pro Parte, Mycocladus). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 2154–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, M.; et al. Risk of mucormycosis in diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Cureus 2021, 13, e18827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, G.; Lynch, J.P.; Fishbein, M.C.; Clark, N.M. Mucormycosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 099–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corzo-León, D.E.; Chora-Hernández, L.D.; Rodríguez-Zulueta, A.P.; Walsh, T.J. Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of reported cases. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Sarkar, P.; Chandak, T.; Talwar, A. Diagnosis and Management Bronchopleural Fistula. Indian J. Chest Dis. Allied Sci. 2022, 52, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, M.; Go, T.; Yokomise, H. Risk factor of bronchopleural fistula after general thoracic surgery. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Agnol, G.; Vieira, A.; Oliveira, R.; Ugalde Figueroa, P.A. Surgical approaches for bronchopleural fistula. Shanghai Chest 2017, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Edwards, J.; Ibrahim, A. Novel Perspectives on Mucormycosis: Pathophysiology, Presentation, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, R.; Yeldandi, A.; Savas, H.; Parekh, N.D.; Lombardi, P.J.; Hart, E.M. Pulmonary mucormycosis: Risk factors, radiologic findings, and pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2020, 40, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekki, S.O.; Hassan, A.A.; Falemban, A.; Alkotani, N.; Alsharif, S.M.; Haron, A.; et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis: A case report of a rare infection with potential diagnostic problems. Case Rep. Pathol. 2020, 2020, 5845394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Liu, X.; Lv, X. Pulmonary mucormycosis as the leading clinical type of mucormycosis in western China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 770551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danion, F.; Coste, A.; Le Hyaric, C.; Melenotte, C.; Lamoth, F.; Calandra, T.; et al. What is new in pulmonary mucormycosis? J. Fungi 2023, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).