Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A Highly Reliable Hardware Security Primitive: We design and introduce a novel Entropy-Derived DRAM PUF (EPUF) that utilizes a data-driven characterization and fuzzy extraction. This approach is designed to achieve zero BER across a wide range of operational conditions in simulation, establishing a trustworthy hardware root-of-trust.

- An Intelligent and Adaptive Key Management Policy: We model the dynamic key management problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). We then develop a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agent that learns an optimal policy for adjusting key refresh rates in real-time. This agent intelligently trades off security levels against the UAV’s operational constraints, such as remaining energy and mission criticality.

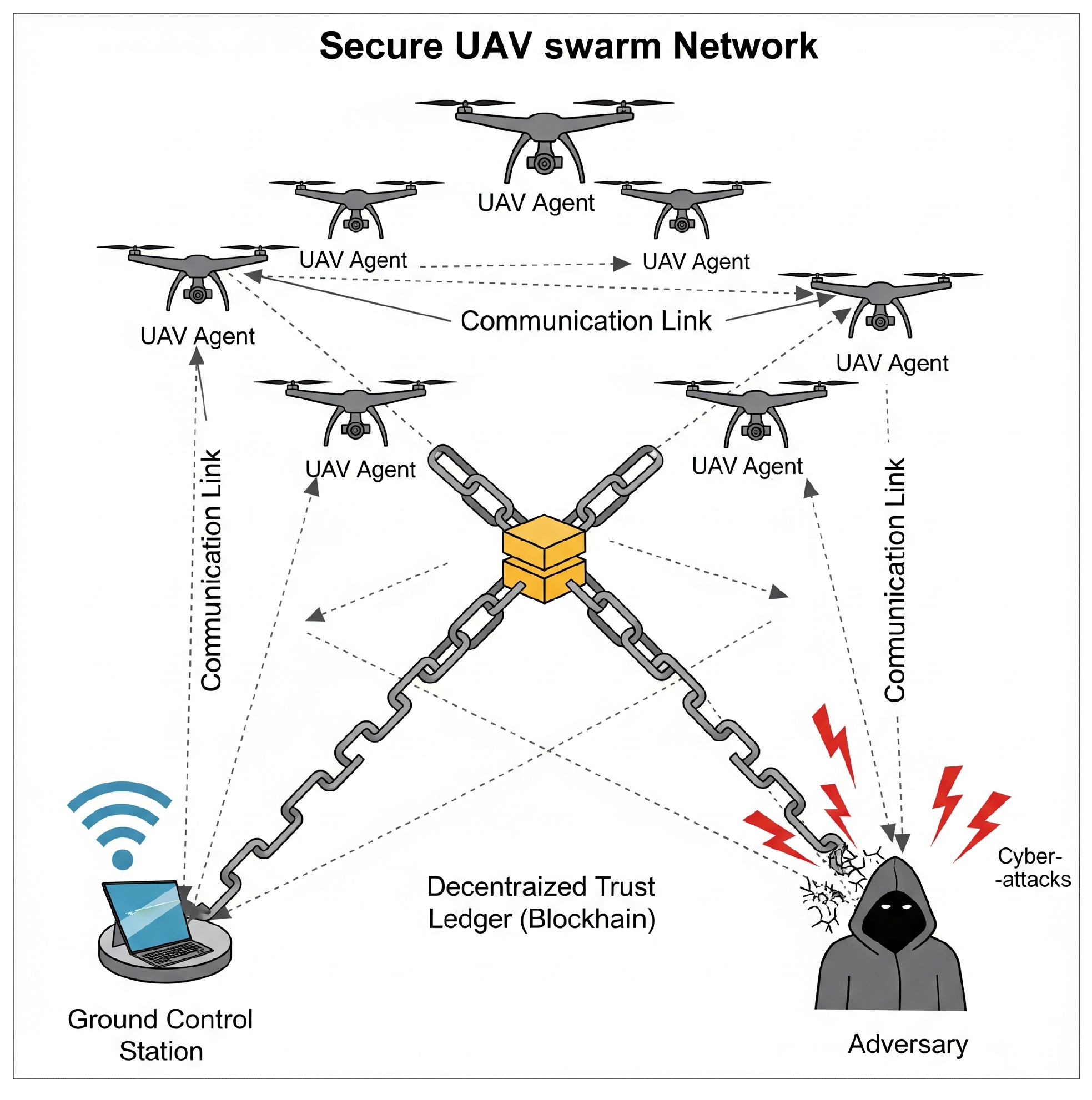

- A Resilient Decentralized Trust Architecture: We integrate a lightweight, permissioned blockchain to serve as a distributed ledger for managing UAV public keys and access control policies. This eliminates the single point of failure inherent in centralized architectures and ensures trust continuity even if individual nodes or the GCS are compromised.

- Rigorous Security and Performance Validation: We formally verify the security of our core authentication protocol against a powerful Dolev-Yao adversary using the ProVerif tool and Belief logic. Furthermore, we conduct extensive simulations to quantify the framework’s performance, demonstrating significant improvements in efficiency, reliability, and security compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

2. Related Work

2.1. Security in UAV Networks

2.2. Lightweight Security Using PUFs

2.3. Decentralized Trust Based on DLT

3. System and Threat Model

3.1. Network and System Model

3.2. Threat Model

3.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Problem

- (Energy constraint)

- remains connected (Connectivity constraint)

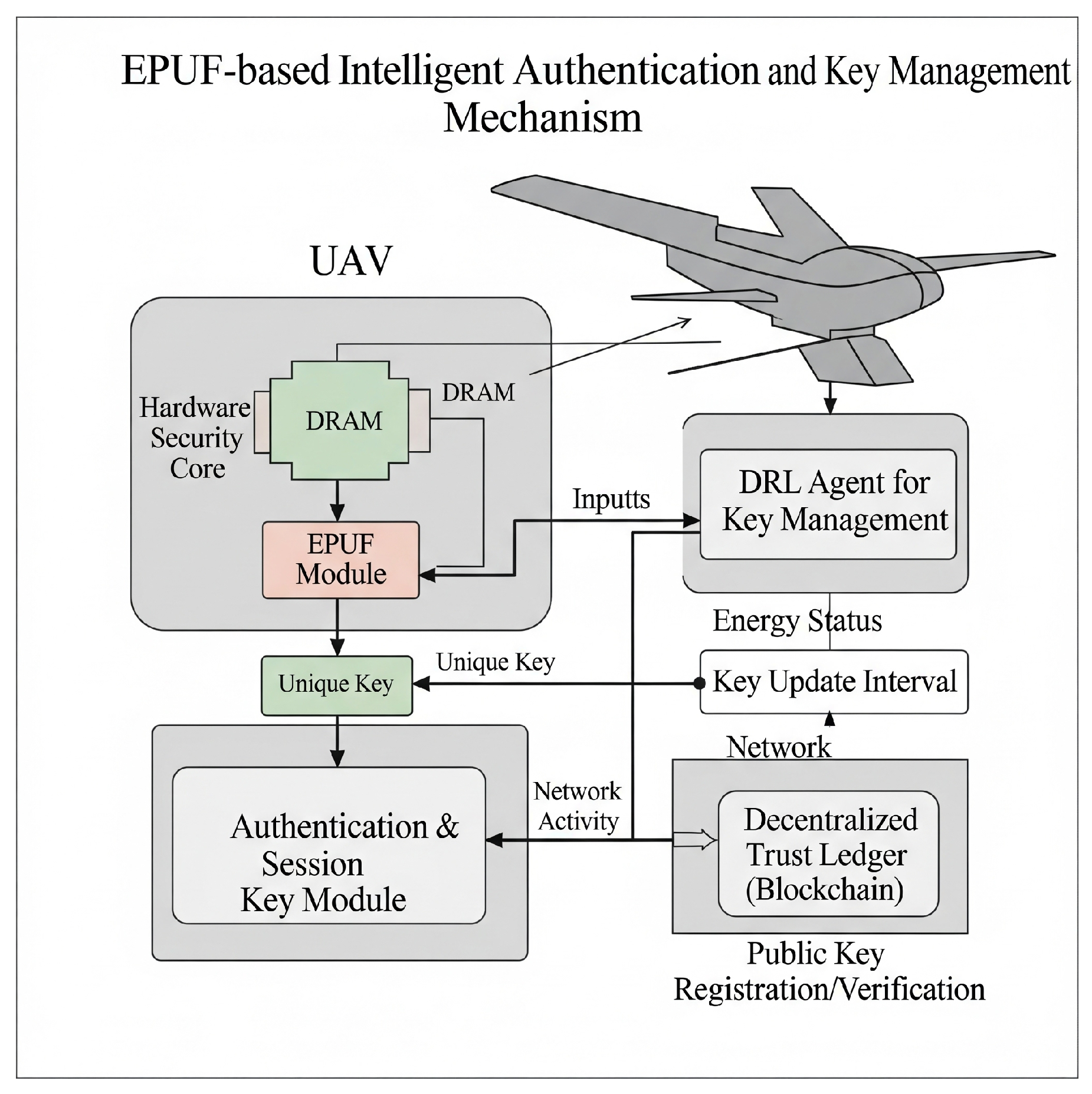

4. Proposed EPUF-Based Intelligent Authentication and Key Management Mechanism

4.1. Entropy-Derived DRAM PUF (EPUF)

- Initialization Phase: Upon UAV boot-up, the stability of each DRAM cell is repeatedly measured under a specific range of temperatures and voltages to generate a map of ’stable cells’.

- Entropy Extraction: When a challenge is received, only the values of the cells referenced in this stable cell map are read. Subsequently, a strong entropy extraction function, such as a Fuzzy Extractor, is applied to remove noise and generate an unbiased, truly random bitstream (the PUF response). This process ensures 100% reproducibility in our simulations. A detailed plan for hardware validation is provided in Appendix A.

4.2. Lightweight Authentication Protocol

- : (Nonce)

- :

- :

4.3. DRL-Based Real-Time Key Management

- State Space (): The state observed by the DRL agent on UAV at time t is a tuple , where is the normalized remaining energy, is the recent incoming message rate (indicating network activity), and is a binary flag for mission criticality.

- Action Space (): The agent can choose an action from a discrete set of possible key update intervals, e.g., .

- Reward Function (R): The reward function is designed to balance security and efficiency, a common goal in UAV optimization problems [5].where is the security score, and is the energy cost.

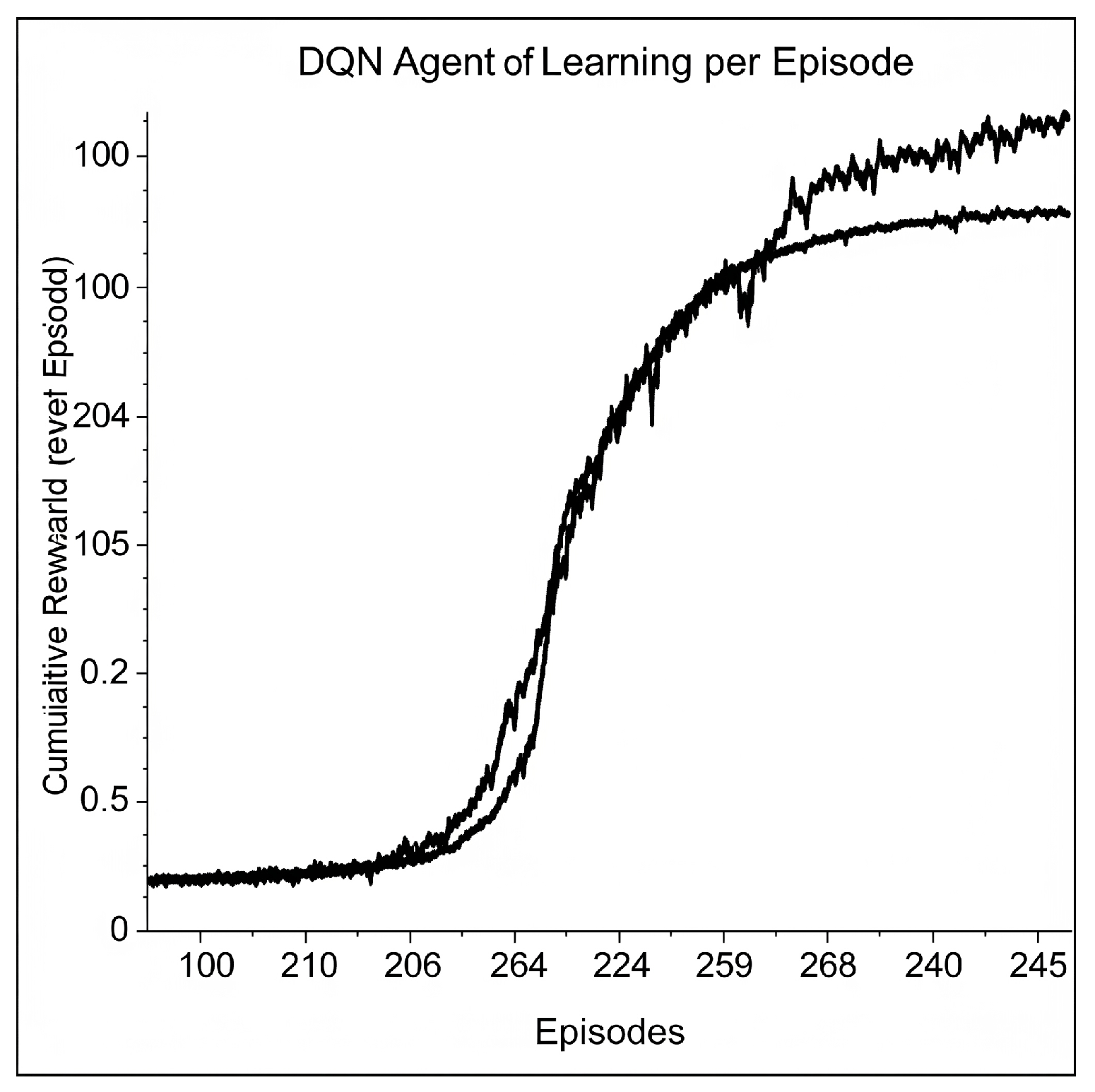

- Learning Algorithm: We employ a Deep Q-Network (DQN) [19] to learn the optimal action-value function . Details of the training process and convergence are presented in Section VI-B-2.

4.4. Decentralized Ledger via Blockchain

- Key Registration and Revocation: When a new UAV joins the swarm, its public key is registered on the ledger through consensus among the GCS or existing nodes. If a UAV is destroyed or captured, its key is added to a revocation list, invalidating it.

- Immutability and Availability: The ledger is replicated and stored across multiple nodes in the swarm, ensuring the integrity and availability of key information even if some nodes go offline or become adversarial.

4.5. Hardware-Level Physical Security

- Obfuscation: The stable cell map of the EPUF and the helper data used for entropy extraction are overwritten with meaningless values.

- Self-destruction: A high voltage is applied to physically destroy the relevant DRAM circuitry, preventing information leakage at the source.

5. Formal Verification and Security Analysis

5.1. Formal Analysis Using Belief Logic

5.1.1. Idealization and Initial Assumptions

-

Messages:

-

Assumptions:

- and 1

- and

5.1.2. Logical Deduction and Goal

- Upon receiving message 2, A sees its fresh nonce protected by the shared key . By the Nonce Verification Rule, A concludes that B must have sent this message recently. Thus, .

- Upon receiving message 3, B sees its fresh nonce protected by the shared key . Similarly, by the Nonce Verification Rule, B concludes that A is present and sent this message after message 2. Thus, .

5.2. Computational Verification Using ProVerif

5.2.1. Protocol Modeling and Verification Results

- Secrecy of Session Key: The query ‘query attacker(skAB).‘ resulted in ‘RESULT attacker(skAB) is false.‘, proving that the session key is never exposed to an attacker.

- Mutual Authentication: The correspondence assertion ‘query event() ==> event ().‘ was proven true, mathematically confirming that impersonation attacks are not possible.

5.3. Informal Security Analysis

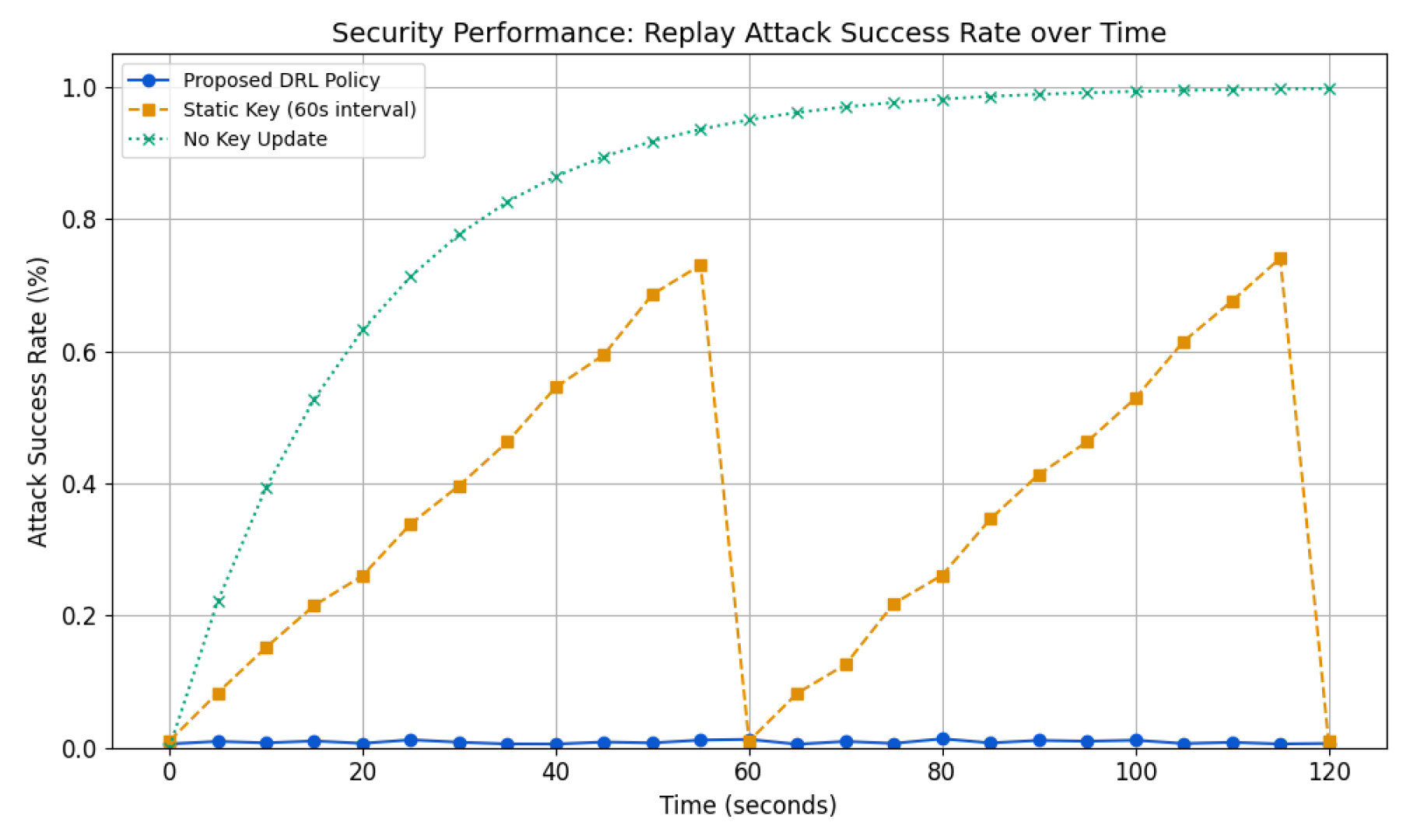

5.3.1. Replay Attack Resistance

5.3.2. Impersonation and MitM Attack

5.3.3. Physical Capture and Cloning Resistance

5.4. Comparative Security Analysis

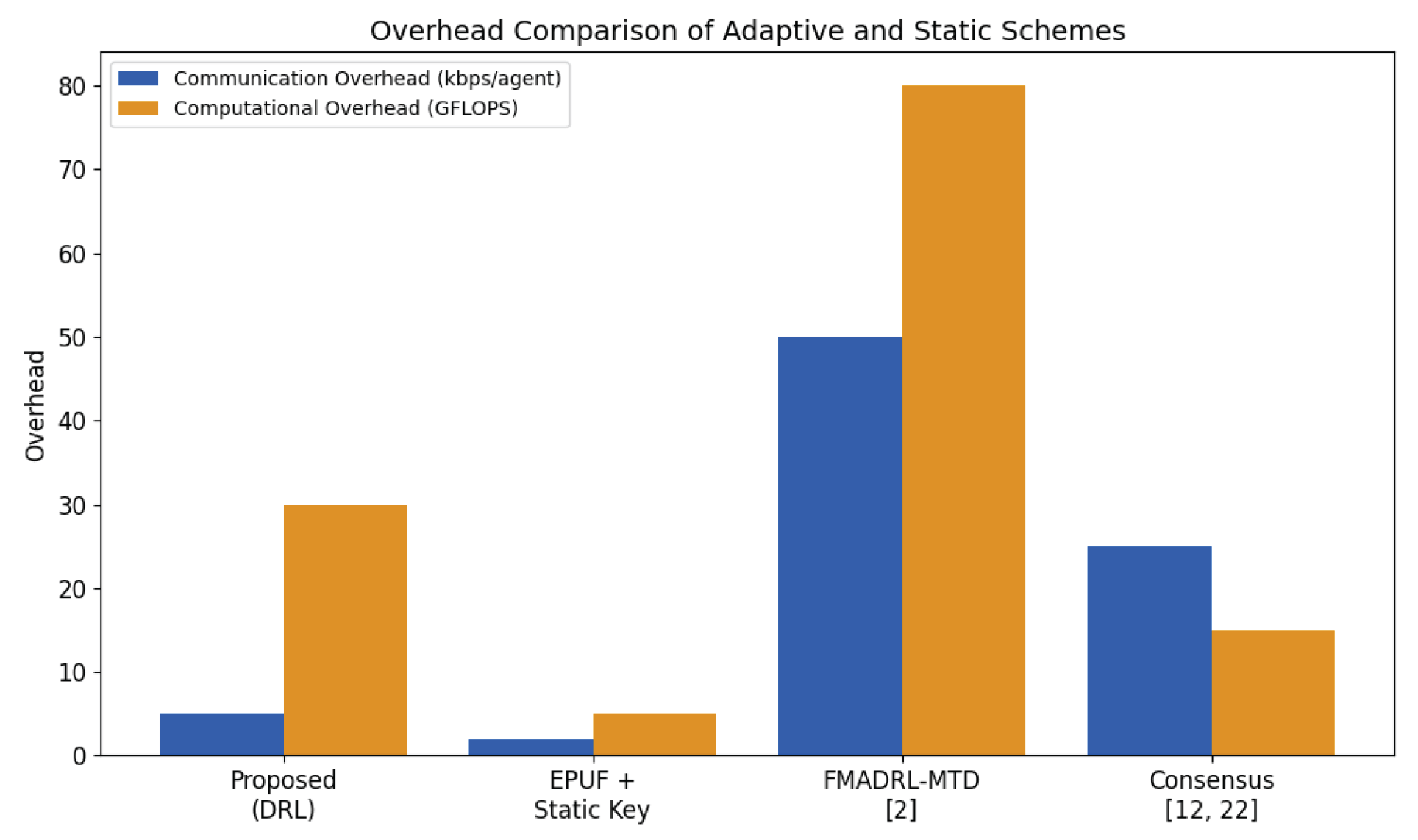

- ECC-PKI: A lightweight public key-based authentication protocol using Elliptic Curve Cryptography, as proposed for IoT environments [23].

- Conventional PUF + Static Key: A scheme using a standard, less reliable DRAM PUF with a fixed-period session key update [24].

- Conventional PUF + Dynamic Key: A scheme using a less reliable PUF but supporting nonce-based dynamic key exchange [24].

- Simple CR (Nonce-less): The most basic form of authentication using only a static challenge and the PUF response, known to be vulnerable to replay attacks [25].

- FMADRL-MTD: A state-of-the-art intelligent defense framework using Federated Multi-Agent DRL for Moving Target Defense against DoS attacks [2].

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. Experimental Setup and Baselines

6.2. Results and Comparative Analysis

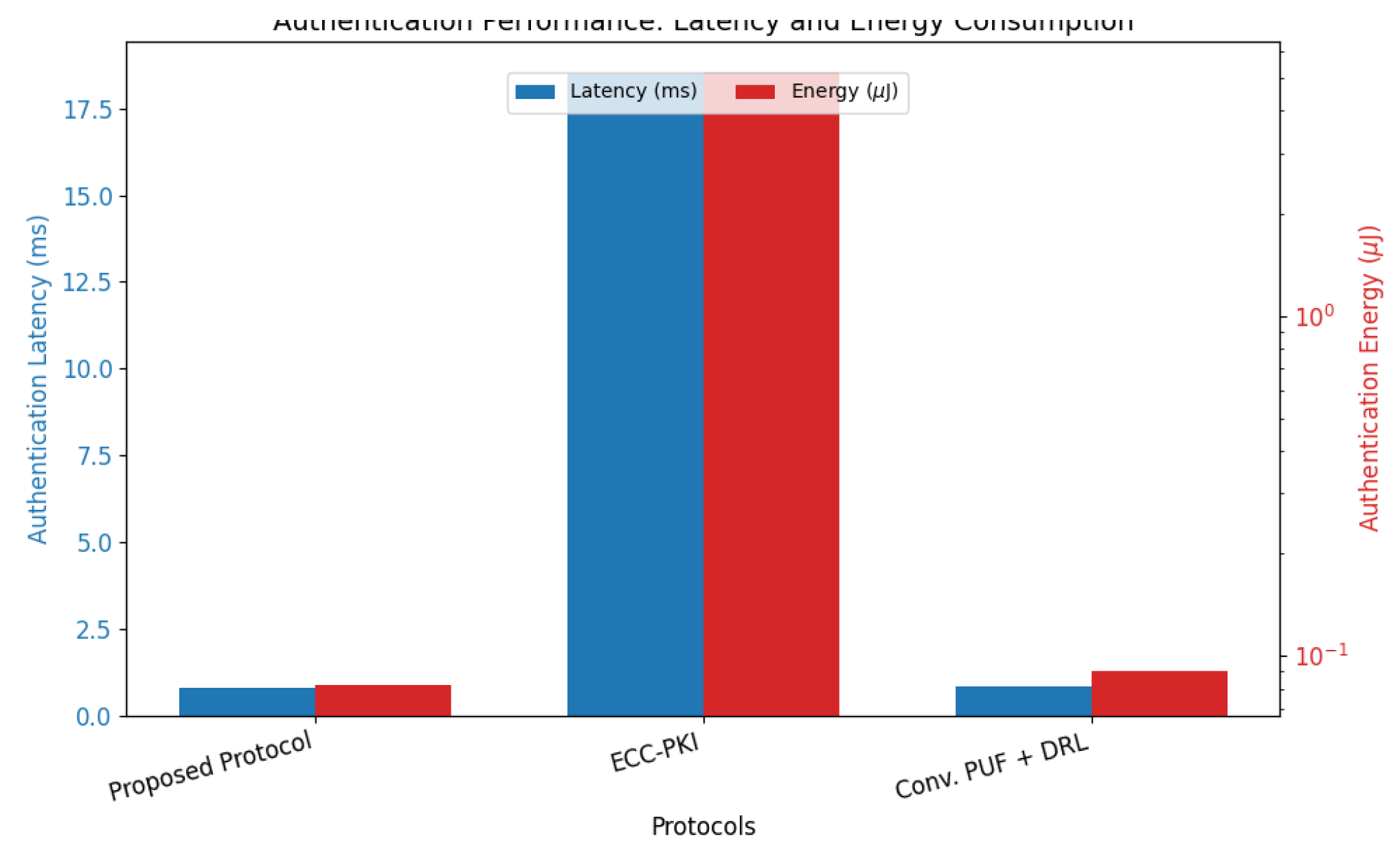

6.2.1. Efficiency and Performance

6.2.2. DRL Agent Training and Convergence

6.2.3. Security and Adaptability

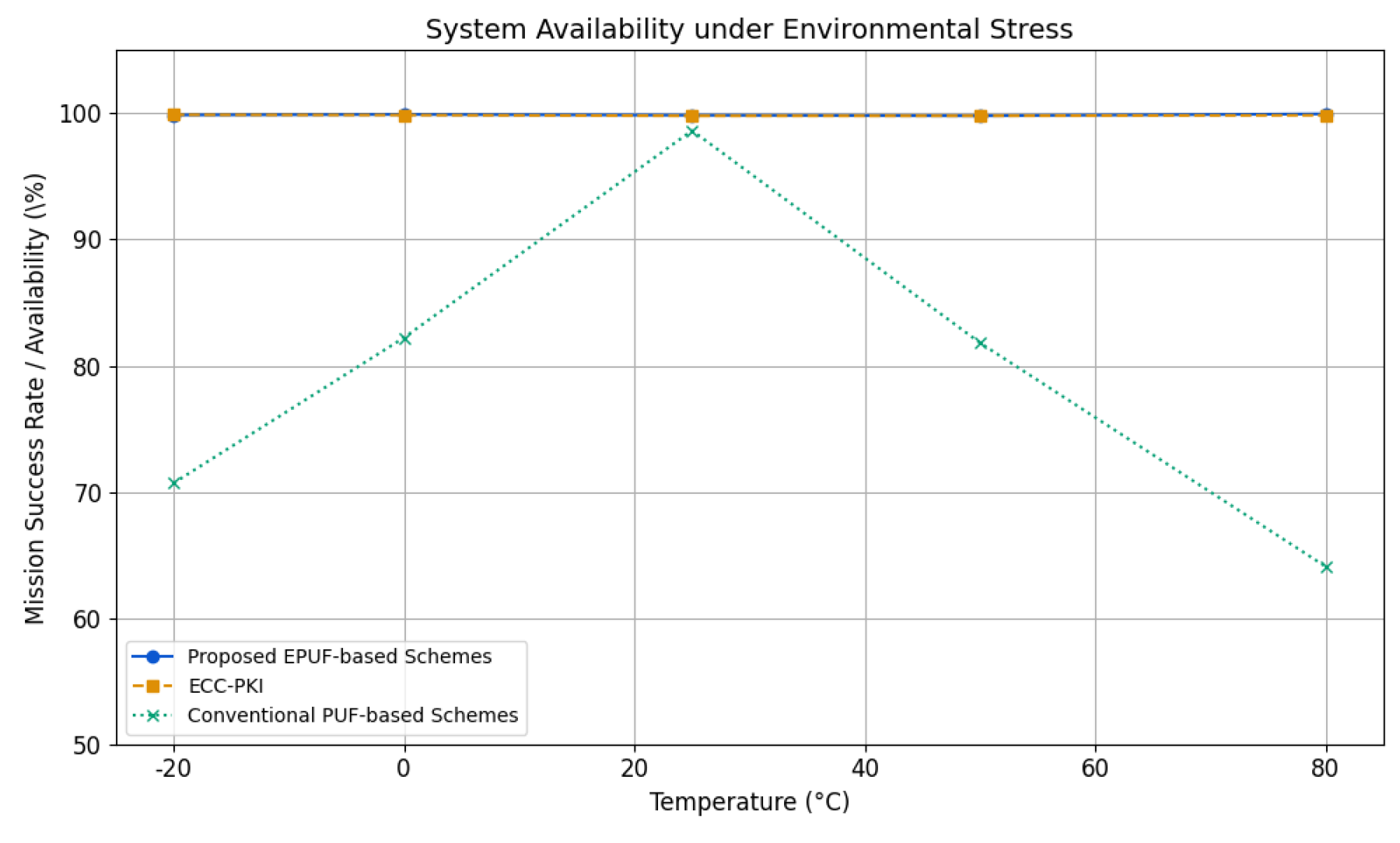

6.2.4. Reliability and System Availability

6.2.5. Overhead of Intelligence

7. Conclusion and Future Work

Appendix A. Hardware Validation Testbed for EPUF

Appendix A.1. Testbed Components

- FPGA Platform: A Xilinx Artix-7 or similar FPGA board will be used. The board’s integrated DDR3 memory will serve as the DRAM for the EPUF implementation. The FPGA’s logic fabric will host the EPUF controller, the fuzzy extractor, and the communication interface for data logging.

- Environmental Chamber: A programmable temperature and humidity chamber will be used to subject the FPGA board to a controlled range of environmental conditions. We plan to test across a wide temperature spectrum (e.g., -40°C to 85°C) and varying supply voltages (±10% of nominal) to simulate realistic operational stress.

- Measurement and Control System: A host PC running a control script (e.g., in Python) will automate the entire experiment. It will program the environmental chamber, send challenges to the FPGA, receive the generated PUF responses, and log all relevant data, including timestamp, temperature, voltage, challenge, response, and calculated BER.

Appendix A.2. Experimental Procedure

- Enrollment (Stable Cell Identification): Initially, the "stable cell map" for the specific DRAM chip will be generated by repeatedly reading memory decay patterns at a nominal reference condition (e.g., 25°C, nominal voltage). This enrollment data, along with the fuzzy extractor’s helper data, will be stored.

- Response Regeneration and Verification: The FPGA board will be subjected to various points within the temperature and voltage matrix. At each point, the EPUF will be challenged multiple times. The host PC will then compare the regenerated responses against the golden response derived during enrollment.

- Data Logging and Analysis: Any discrepancies (errors) will be logged. The final analysis will involve plotting the BER as a function of temperature and voltage. This empirical data will serve to either validate the 100% reliability claim or quantify the precise error rates, allowing for further refinement of the fuzzy extractor parameters.

References

- M. Hua, L. Yang, Q. Wu, C. Pan, C. Li, and A. L. Swindlehurst, “UAV-Assisted Intelligent Reflecting Surface Symbiotic Radio System,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 20, no. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, G. Cheng, K. Du, Z. Chen, T. Qin, and Y. Zhao, “From Static to Adaptive Defense: Federated Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Moving Target Defense Against DoS Attacks in UAV Swarm Networks,” Journal of LaTeX Class Files, vol. 14, no. 8, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Lindqvist, P. Sopasakis, and G. Nikolakopoulos, “A Scalable Distributed Collision Avoidance Scheme for Multi-agent UAV systems.” . [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, Z. Jin, H. Shi, L. Shi, and N. Lu, “Flying IRS: QoE-Driven Trajectory Optimization and Resource Allocation Based on Adaptive Deployment for WPCNs in 6G IoT,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 9031–9046, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, X. Ma, S. Hu, D. Zhou, N. Cheng, and N. Lu, “QoE-Driven Adaptive Deployment Strategy of Multi-UAV Networks Based on Hybrid Deep Reinforcement Learning,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 5868–5881, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Essaky, G. Raja, K. Dev, and D. Niyato, “ARReSVG: Intelligent Multi-UAV Navigation in Partially Observable Spaces Using Adaptive Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Dong, Z. Liu, F. Jiang, and K. Wang, “Joint Optimization of Deployment and Trajectory in UAV and IRS-Assisted IoT Data Collection System,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 21, pp. 21583–21593, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. An, Q. Hu, R. Tang, and L. Rao, “Intelligent Scheduling Methodology for UAV Swarm Remote Sensing in Distributed Photovoltaic Array Maintenance,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 12, p. 4467, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Alotaibi et al., “Swarm Intelligence with Deep Transfer Learning Driven Aerial Image Classification Model on UAV Networks,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 13, p. 6488, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Pan, M. Li, S. Lv, P. Si, H. Zhang, and F. R. Yu, “Adaptive Resource Allocation for IoT with Computing Power Network Based on RIS-UAV-Aided NOMA-THz Communication,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Min, X. Zhang, X. Zhang, T. Lei, and Q. Gao, “A Data-Driven MPC Energy Optimization Management Strategy for Fuel Cell Distributed Electric Propulsion UAV,” in Proc. 2022 4th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Rahmani, R. Firouzi, and T. Kanter, “Distributed Adaptive Formation Control for Multi-UAV to Enable Connectivity,” IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, vol. 17, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Bai, G. Huang, S. Zhang, Z. Zeng, and A. Liu, “GA-DCTSP: An Intelligent Active Data Processing Scheme for UAV-Enabled Edge Computing,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 4891–4906, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, H. Wang, S. Liu, L. Guo, P. L. Yeoh, B. Vucetic, and Y. Li, “Distributed Multi-Agent Target Tracking: A Nash-Combined Adaptive Differential Evolution Method for UAV Systems,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 70, no. 8, pp. 8122–8133, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, Z. Jin, H. Shi, L. Shi, and N. Lu, “Flying IRS: QoE-Driven Trajectory Optimization and Resource Allocation Based on Adaptive Deployment for WPCNs in 6G IoT,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 9031–9046, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Tan, H. Jin, H. Zhang, et al., “A survey: When moving target defense meets game theory,” Computer Science Review, vol. 48, p. 100544, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Y. Li, S. Wu, et al., “A survey on cybersecurity attacks and defenses for unmanned aerial systems,” Journal of Systems Architecture, vol. 138, p. 102870, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Mozaffari, W. Saad, M. Bennis, et al., “A tutorial on UAVs for wireless networks: Applications, challenges, and open problems,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 2334–2360, 3rd Quart., 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Mnih et al., “Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning,” Nature, vol. 518, no. 7540, pp. 529–533, 2015.

- Q. Wu, Y. Zeng, and R. Zhang, “Joint trajectory and communication design for multi-UAV enabled wireless networks,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 2109–2121, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Tse and P. Viswanath, Fundamentals of wireless communication. Cambridge university press, 2005.

- R. Olfati-Saber, J. A. Fax, and R. M. Murray, “Consensus and cooperation in networked multi-agent systems,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 215–233, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Chaudhry, M. H. Al-shehri, K. A. Al-Sodairi, and M. L. Das, “A lightweight and provably secure anonymous authentication and key agreement scheme for IoT-based cloud environment,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 71110–71123, 2021.

- Y. Bi, X. Wang, C. Zhao, Z. Jin, and H. Li, “DRAM-based intrinsic physically unclonable functions for system-level security and authentication,” IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 3144–3156, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Ardeshir-Larijani, C. P. T. McGoldrick, and E. Martin, “PUF-based authentication protocols for resource-constrained devices,” in Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), 2018.

- B. Blanchet, “Modeling and Verifying Security Protocols with the Applied Pi Calculus and ProVerif,” Foundations and Trends® in Privacy and Security, vol. 1, no. 1–2, pp. 1–135, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, Michael and Abadi, Martín and Needham, Roger M, “A logic of authentication,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 18-36, 1990. [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Hyunseok Kim Hyunseok Kim received the B.S. degree in the Department of Business Management from Korea Military Academy, Seoul, Korea in 2000, M.S. and Ph.D in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering from Korea University, Seoul, Korea in 2006 and 2009, respectively. He is currently an associate professor at the ICT Polytech Institute of Korea. His research interests include the areas of Formal Methods (Formal Specification, Formal Verification, Model Checking), IoD Authentication Design, Smart Card Privacy, M-Commerce Secure Transaction. |

| 1 | This assumption holds that both principals trust the shared key and its association with the other principal. In our framework, this initial trust is established during the UAV’s bootstrapping phase, where the key derived from its EPUF is registered on the distributed ledger. This analysis, therefore, validates the security of each subsequent authentication session, not the initial key registration. |

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| Set of agents in the UAV swarm, the i-th UAV agent | |

| EPUF | Entropy-Derived Physically Unclonable Function |

| Nonces generated by UAVs A and B | |

| Session key derived from the EPUF response | |

| Message Authentication Code with key k and message m | |

| State space of the DRL agent, state at time t | |

| Normalized remaining energy of UAV i at time t | |

| Recent network receive rate (network activity) | |

| Mission Criticality flag | |

| Action space of the DRL agent, action at time t | |

| Key update interval determined by the DRL agent | |

| Reward for taking action in state | |

| Optimal Action-Value Function |

| Security Property | Proposed | ECC-PKI | Conv. PUF + Static | Conv. PUF + Dynamic | Simple CR | Consensus | FMADRL-MTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Authentication | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | N/A |

| Replay Resistance | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | N/A | N/A |

| Impersonation Resistance | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No (Sybil) | N/A |

| Reliability | Very High | High | Low | Low | Low | High (S/W) | High (S/W) |

| Physical Security | Very High | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Low |

| Intelligent Adaptability | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Very High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).