INTRODUCTION

Intoxication of thinner, which is among the volatile organic solvents in the modern world used widely at home and in industry in our daily lives, has become an increasing public healthcare concern threatening children in recent years. The widespread use of volatile organic solvents, which are also used as narcotics, has made this concern even more current [

1].

Thinner, which is used as a solvent in the paint industry, is a mixture of various aromatic hydrocarbons (i.e., benzene, toluene, and xylene), halogenated hydrocarbons (i.e., carbon tetrachloride, methane and trichloroethylene) and naphthalene (e.g., N-hexane) and is an organic solvent used widely in the industry in the production of plastics, varnishes, paints and adhesives, in painting and decoration applications such as thinning oil-based paint, cleaning brushes, and removing household paints [

2,

3]. Thinner is often found in homes and it is very easy for children to reach thinner if it is not stored properly because of the nature of these applications. Storing thinner in different packages, such as water, fruit juice, or soda bottles, especially at home, makes it easier for children to accidentally drink this substance.

Thinner intoxication is life-threatening and affects the central nervous system and respiratory system. It also affects almost all systems because it is a toxic compound because of exposure to toluene and xylene, depending on the duration, frequency, and amount of use [

4]. Thinner intoxication may also cause fever, headache, restlessness, vomiting, nausea, auditory and visual hallucinations, aplastic anemia, central nervous system depression, pulmonary toxicity, rhabdomyolysis, metabolic disorders (acidosis), hepatic and renal toxicity findings, methemoglobinemia, dysrhythmia, loss of consciousness and sudden death [

5,

6]. The most common cause of mortality caused by organic solvents is arrhythmia and cardiac arrest, which occur suddenly when the myocardium becomes sensitive to catecholamines. Chronic intoxication is frequently observed because of the abuse of solvents such as thinner among industrial workers who inhale solvent vapors [

7].

Pediatricians must be aware of symptoms of toxicity and provide information about toxicity because of acute or chronic paint-thinner exposure. However, there are very few studies in the literature on the mechanisms, biochemical abnormalities, and symptoms of thinner poisoning. The present study was planned to draw attention to the need to take more serious precautions in the packaging, selling, and use of organic solvents (e.g., thinner), to determine the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of poisoning because of this substance, and to draw attention to its possible complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The patients who drank thinner and applied to the pediatric emergency clinic of Selçuk University Faculty of Medicine Hospital between January 2017 and December 2020 were examined in the present study. Forensic cases were identified by examining the forensic case books and the data in the hospital registry system. The medical data of the patients were examined retrospectively according to the files and recorded in the created form. Those who were not forensic, over the age of 18, trauma patients, whose files could not be accessed or whose files had serious information gaps were not included in the study.

The age and gender of the patients, date and time of admission to the pediatric emergency department, season of admission, method of admission, time to reach the hospital, follow-up and treatment methods in the emergency department, method of intake of the pharmacological agent that caused poisoning, fate of the patient, place of follow-up, requested tests and their results were evaluated. Vital signs at the time of initial admission were evaluated and the need for urgent effective supportive treatment was determined.

Application hours were divided into 3 groups (00:00-08:00, 08:00-16:00, and 16:00-00:00). Whether it was the first hospital that the cases applied to regarding the incident was evaluated quantitatively, and the time between the incident and the time of admission was evaluated in hours. All the cases were evaluated according to the presence of symptoms as the reason for admission.

The hemogram, biochemistry, coagulation, and blood gas values of the patients were examined along with PA chest radiography. In the hematological parameters of the patients, total leukocyte count <4000 was considered as leukopenia, >11 000 as leukocytosis, neutrophil count <1500 as neutropenia, lymphocyte count <1500 as lymphopenia, and hemoglobin value <11 g/dL as anemia.

The cases were then evaluated quantitatively in terms of follow-up times in hours and recommendations for follow-up in the intensive care unit.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows 23.0 program was used for the data obtained from the study. When the study data were evaluated, the “Mann-Whitney Test” was used to compare quantitative data between two The results were evaluated at the significance level of p<0.05.

RESULTS

The total number of poisoning cases admitted to the pediatric emergency clinic of Selçuk University Faculty of Medicine Hospital between January 2017 and December 2020 was 1404. The 38 cases of thinner intoxication that were presented to the pediatric emergency department of our hospital made up 2.70% of all poisoning cases.

Among the patients who participated in the study, 27 (71.1%) were male and 11 (28.9%) were female. The average age of the patients was 48.05±23.48 months (19-113 months) and the median value was 42.50 months. No statistically significant differences were detected in the mean age according to gender (p:0.974). The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients included in the study are given in

Table 1.

A total of 37 (97.4%) of the patients included in the study were poisoned by oral route and only one (2.6%) was found to be poisoned by inhalation. All patients with oral poisoning had accidentally drank the thinner placed in a water bottle. Also, the Poison Control Center (114) was called for 31 (81.6%) of the patients, but gastric lavage and activated charcoal were not applied because they were not recommended. The average time between poison ingestion and admission to the pediatric emergency department was 121.92±221.83 minutes (min-max: 20-900 minutes).

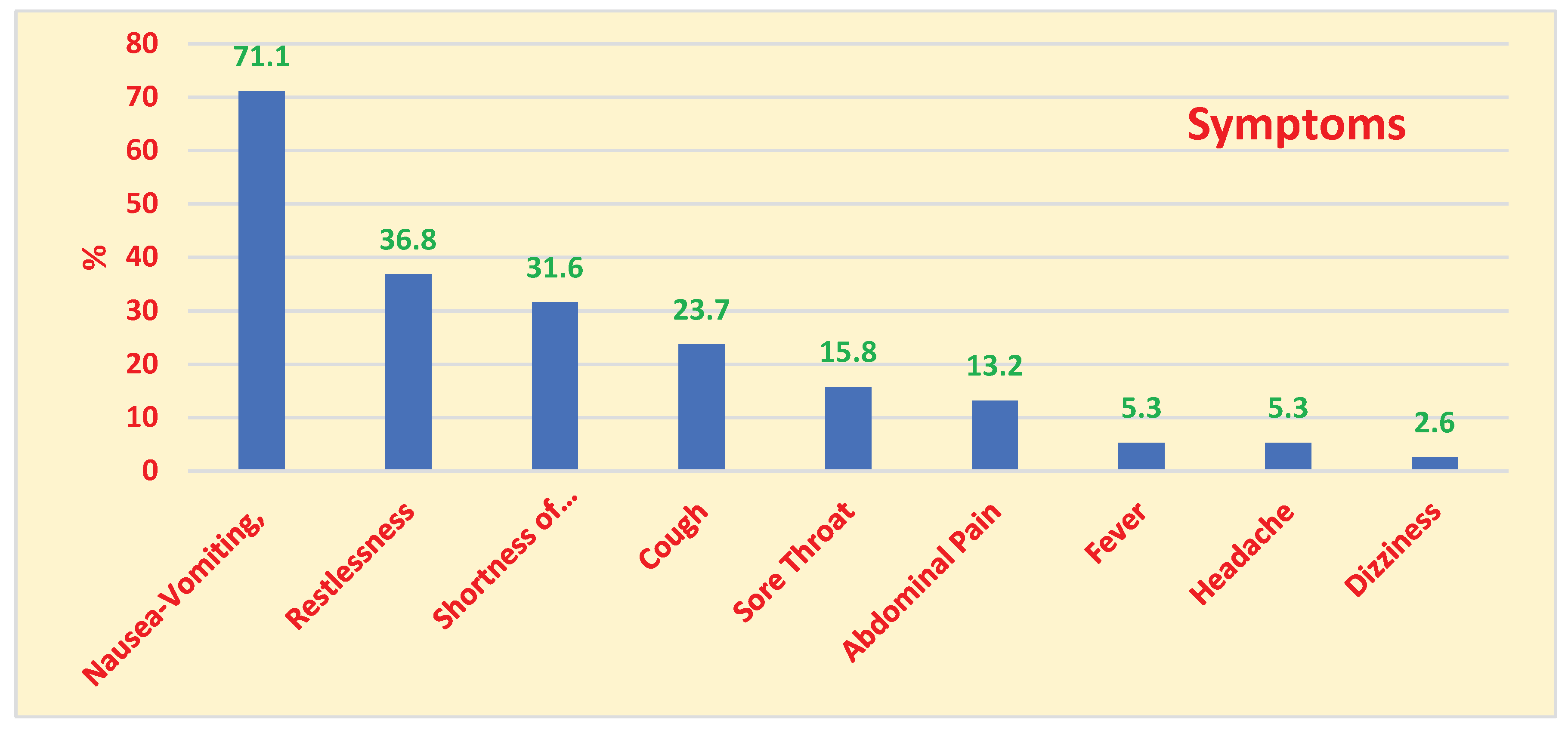

A total of 27 (71.1%) of the patients had nausea and vomiting, 14 (36.8%) had restlessness, and 12 (31.6%) had shortness of breath. The distribution of the patients admitted to the pediatric ward with thinner poisoning according to symptoms is given in

Figure 1. It was found that the families forced vomiting in 13 (34.2%) of the children after drinking paint thinner. Findings of pneumonia developed in 9 (23.7%) patients during the follow-up of the patients in the ward and emergency observation. There was infiltration in the chest radiography taken in 5 of these patients (13.2%). A total of 2 (5.3%) patients developed a fever during the follow-ups and antibiotic treatment was administered to patients with pneumonia. Methemoglobinemia was detected in only one of the patients (2.6%).

When the laboratory values of the patients who participated in the study were examined, there was leukocytosis in 19 (50.0%) cases, lymphopenia in 1 (2.63%) case, and anemia in 5 (13.15%) cases. When the hemogram and biochemical parameters of the patients were examined, no abnormalities were detected. The hemogram and biochemical parameters of the patients are given in

Table 2. When blood gases taken from the patients were examined, pH: 7.37 ± 0.03, pO2: 49.96 ± 16.88 mmHg, pCO2: 39.81 ± 8.57 mmHg, HCO3: 23.01 ± 4.76 mEq/l, O2 sat: 72.41 ± 22.26 %. The saturation value was <90% in 11 (28.9%) patients and metabolic acidosis was detected in 3 (7.9%) patients in the present study. Blood gas values of patients with thinner poisoning are given in

Table 3.

When the final results of the patients who applied to the pediatric emergency department were examined after the examination in the emergency room, it was found that 13 (34.2%) of the patients received inpatient treatment in the pediatric health and diseases clinic, and 20 (52.6%) were followed up in the pediatric emergency observation room. It was found that 5 of the patients (13.2%) voluntarily refused treatment and follow-up and were discharged. The duration of hospital stay was 20.48±7.74 hours (min-max: 1-24 hours). All patients received oxygen support, intravenous serum therapy, and standard supportive and symptomatic treatment. No patients who were treated died in the study.

DISCUSSION

The issue is a social problem all over the world because organic solvents are a part of our daily lives [

8]. Poisoning cases because of volatile thinner are mostly reported in the literature as case reports or studies conducted with adults [

9]. Studies conducted on this subject in childhood are very few in the literature. The most common clinical symptoms and laboratory abnormalities that may occur during acute poisoning in children were evaluated in the present study.

Poisoning cases because of organic solvents constitute 5-10% of all poisoning cases in studies conducted in our country [

10]. Thinner intoxication constituted 2.70% of all poisoning cases in our study. More studies are needed on this subject in children because of insufficient literature data.

The fact that thinner is sold in packages such as water, fruit juice, or soda bottles and the lack of adequate supervision increases the possibility of poisoning children with these solvents. Most of the poisoning cases (97.4%) were because of ingestion of paint thinner used at home as paint thinner in the present study. Only one (2.6%) patient was found to have been poisoned by inhalation.

Indoor painting work is generally done in the spring and summer months and thinner is often used as a paint thinner. This suggests that it is one of the most common causes of thinner-related poisoning in childhood in our area. In the study conducted by Güzel et al., when the distribution of cases according to seasons was examined, it was found that the most common poisoning cases occurred in summer [

11]. It was found that most cases of poisoning were admitted to the pediatric emergency department in the summer months, with a rate of 42.1% in the present study.

Previous studies show that in the western and southern regions of our country, poisoning cases are brought to the hospital early, but admissions to the emergency department are later in the eastern and northern regions [

10]. Factors affecting this include socioeconomic status, education levels, transportation conditions, and adequacy of healthcare services. In the study conducted by Güzel et al., when the admission times of patients to the hospital were examined, it was found that they were most frequently brought to the pediatric emergency clinic in the evening hours (51.4%) [

11]. In the present study, it was found that the most frequent application was in the evening (68.4%). When we evaluated the conditions in our area, these application hours can be explained by the fact that working mothers and fathers bring their children to the emergency departments during the hours that coincide with their return from work.

Thinner contains 40-60% toluene and different amounts of methanol, N-hexane, benzene, and xylene in different brands. However, the standardized rates for thinner are 90% toluene, 9% ethyl acetate, and less than 1% benzol mixture in our country [

12]. For this reason, the effects related to the more toxic toluene occur more prominently, and a clinical course that parallels the blood level is often observed especially in paint thinner intoxications [

13]. However, some publications accept different rates as criteria for the blood toluene levels that cause the disease [

14]. In the present study, there were no findings in the files about the thinner contents taken and the blood toluene levels of the cases.

Symptoms and findings caused by acute thinner poisoning include fever, restlessness, vomiting, nausea, asthma, sore throat, abdominal pain, drowsiness, dizziness, agitation, cough, drowsiness, diarrhea, central nervous system depression, hepatic and renal toxicity findings, methemoglobinemia, rhabdomyolysis, electrolyte abnormalities, and dysrhythmia [

4,

9,

15]. Chronic poisoning may cause clinical symptoms secondary to central nervous system pathologies such as cerebellar ataxia, visual disturbances, tremors, and gait disorders [

16]. These findings mostly develop after drug use, which has also been described as thinner addiction in recent years, or because of long-term exposure in people working in the paint industry [

1,

16]. For this reason, chronic poisoning symptoms generally appear in the adult age group. The most common reasons for admission were nausea-vomiting (71.1%), restlessness (36.8%), and tachypnea (31.6%) in the present study.

Among the symptoms and findings associated with thinner poisoning, the most feared one is aspiration pneumonia. Vomiting that often occurs during oral intake of these solvents or direct inhalation is the cause of aspiration pneumonia [

8]. Episodes of coughing, retching, and choking that occur shortly after oral intake (the first 30 minutes) are considered evidence of possible aspiration [

8]. Ingestion or inhalation of less than 1 mL of some hydrocarbons was shown to cause chemical pneumonia and death. Respiratory symptoms usually start within the first few hours after the exposure and usually resolve within 2-8 days. Symptoms such as cough and bronchial congestion might also occur shortly after oral intake and may be followed by tachypnea, wheezing, and chemical pneumonia. In such cases, death may occur because of chemical exposure, which is often associated with bacterial infections and other respiratory complications [

17]. Inducing vomiting in such patients is not recommended because it may increase the risk of pulmonary complications as a result of aspiration [

18]. Radiological findings of aspiration pneumonia appear in the first six hours at the earliest in these patients. Even if clinical symptoms improve, pathological infiltration findings on chest radiography may persist for a long time. For this reason, clinical findings are much more important than radiological findings. For this reason, there is no correlation between radiographic improvement and clinical improvement [

8]. However, these cases are diagnosed with bacterial pneumonia and usually receive antibiotic treatment because of the combination of high fever and leukocytosis along with respiratory findings that develop during follow-ups [

8]. It must also be noted that the disease progresses rapidly with serious findings such as multiple organ failure and ARDS in 5% of cases with pneumonia [

19]. In the present study, pneumonia findings occurred in 23.7% of the cases. There was infiltration in the chest radiography in 5 of these patients (13.2%). Two (5.3%) patients developed a fever during the follow-ups. Antibiotic treatment was administered to patients with pneumonia. The emergence and persistence of fever 48 hours after hydrocarbon aspiration, increased infiltration, leukocytosis, or sputum on chest radiography must suggest aspiration pneumonia.

It is recommended to monitor routine biochemical laboratory test results (e.g., arterial blood gas, liver, and kidney function) in patients with thinner poisoning. Studies show that metabolic acidosis and hypoxia are among the serious complications caused by paint thinner intoxication [

20]. Saturation values were <90% in 11 (28.9%) patients, metabolic acidosis was detected in 3 (7.9%) patients in the present study and there were no abnormalities in electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests.

Methemoglobin (MetHb) is an oxidized form of hemoglobin, is a weak oxygen carrier, and cannot carry oxygen to tissues [

21]. Methemoglobinemia can be acquired or congenital and is characterized by higher than normal levels of MetHb in the blood, which results in a decreased ability to release oxygen to tissues and tissue hypoxia when MetHb is in high concentration, which can cause tissue hypoxia, cyanosis, dyspnea, headache, seizures, acidosis, cardiac arrhythmias, coma, and even death [

22]. On a global scale, drug- and toxin-induced MetHb is more common when compared to the congenital form. Although paint thinners are regularly used in the printing sector, methemoglobinemia caused by paint thinner intoxication was rarely reported [

23]. Only one (2.6%) patient developed methemoglobinemia in the present study.

The treatment of acute paint thinner poisoning is supportive and conservative. It is very important to maintain cardiorespiratory functions and remove the patient from the source of exposure. Supplemental oxygen is administered to increase the clearance of paint thinner from the respiratory tract. Epinephrine and other catecholamines must be used with caution to treat arrhythmia [

24]. Slow intravenous injection of methylene blue can relieve thinner-poisoned patients from severe hypoxic symptoms [

4,

23]. Inducing vomiting and gastric lavage are contraindicated in the treatment of thinner intoxications. There is no benefit from using activated charcoal [

8]. The treatment includes supportive practices in cases of aspiration-related pneumonia. It is not routinely recommended because the use of steroids is not effective in these cases [

8]. In the present study, it was found that families often made their children vomit after taking the substance. Activated charcoal was not administered to any of the cases in the emergency department. No arrhythmia complications developed in any case during the follow-ups.

Our study has several limitations. First, it included only a few patients. In addition, the independent effect of recovery could not be evaluated because this was not a randomized controlled trial.

Pediatric emergency physicians must be aware of lung complications even with oral exposure to thinner. For this reason, the emergence of local pulmonary complications along with possible systemic complications such as central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract toxicity, arrhythmias, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis, as well as pneumonia, must be closely monitored. The absence of symptoms or radiological findings right after ingestion of thinner or any chemical substance, or the presence of only short-term symptoms, is probably determined by the amount and physical characteristics of the substance reaching the tracheobronchial tree. For this reason, pediatric emergency physicians must be careful that serious complications might develop in patients exposed to chemicals whose physical findings are initially normal. Patients with a history of exposure to any chemical substance must be hospitalized for at least twenty-four hours after the exposure to monitor local and systemic toxic effects. In conclusion, it is very important to take more serious precautions in the sale, packaging, and use of substances that might affect vital functions in poisoning, such as paint thinner, and especially to provide routine training to families on this subject.