1. Introduction

The abundance of multilingual material and the global character of information interaction in the modern evolving digital world have created both unparalleled potential and severe problems in the disciplines of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and AI [

1]. Deciphering the mood behind the broad range of textual data created across languages has emerged as a crucial challenge with substantial consequences for a variety of applications as the world becomes interconnected through the internet [

2]. This phenomenon has sparked tremendous interest and study into the use of AI models for sentiment analysis via cross-lingual transfer learning [

3].

Moreover, a developing field in NLP and AI called "cross-lingual sentiment analysis" attempts to solve the problem of interpreting the emotional tone of writing in several languages. The ability to comprehend thoughts conveyed in several languages has become essential for a variety of applications in a world where there is a growing amount of multilingual material and connections. Cross-lingual sentiment analysis broadens the scope to include a variety of languages, in contrast to standard sentiment analysis, which concentrates on a single language. This method includes analyzing sentiments across languages and cultures by using transfer learning techniques and AI models. In this procedure, transfer learning models—which are renowned for their capacity to identify intricate language correlations and patterns—are indispensable. These models enable interpreting textual material in several linguistic settings by utilizing prior information from one language to comprehend attitudes in another.

On the other hand, the study of sentiment, which involves identifying the emotional tone expressed in written material, is of utmost importance in comprehending public opinion and feeling in many languages [

4]. Cross-lingual sentiment analysis, a nascent discipline, expands the aforementioned capabilities to encompass a multitude of languages. This study summarizes the current trends and issues related to implementing AI models in the field of cross-lingual sentiment analysis.

Furthermore, NLP has a significant place within the domain of Intelligent Systems, alongside machine vision and pattern recognition. Language plays a crucial role in the process of encoding and distributing information, distinguished by its carefully structured grammar [

5]. Nevertheless, researchers are faced with significant obstacles when dealing with the complex network of several languages, changes in dialects, contextual subtleties, and even little variances in communication channels [

6]. As a result, the endeavor to achieve universal language modeling and comprehension has given rise to several sub-domains. The methods encompassed in this category consist of surveys, photo description, and captioning, text classification and summarization, machine translation, and natural language production [

7]. It is worth mentioning that attention mechanisms have become a prevalent characteristic in state-of-the-art methodologies, allowing systems to assign priority to particular phrases or paragraphs depending on their relevance and significance.

In the field of NLP, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have gained considerable recognition and accomplished notable advancements [

7]. Nevertheless, the computing requirements for using RNNs to capture complex associations among words or text segments are significant. The accurate representation of these complex interconnections is of utmost importance in tasks such as text production and comprehension in intelligent systems. The use of RNNs in such situations has the potential to negatively affect performance [

8]. To mitigate these constraints, Vaswani et al. (2017) proposed the use of the Transformers architecture [

9]. The primary aim of this study was to utilize attention processes while addressing challenges related to sequential processing. The Transformers model rapidly gained prominence as the prevailing framework in a substantial portion of NLP, accumulating more than 4,000 citations and making noteworthy contributions since its initial release in December 2017. The sector had a significant increase in growth, leading to a shift in focus towards the development of bigger models incorporating weighted Transformers and enlarged contextual frameworks. This movement indicates a departure from task-specific learning approaches and a move towards more comprehensive language modeling. Nevertheless, despite the remarkable ability of modern algorithms to produce very intricate content, their primary reliance is on statistical data extracted from text corpora, rather than understanding the underlying core of language. As a result, the resulting output frequently consists of segments that have moderate relevance, which are occasionally interrupted by sequences that are difficult to understand. This is a challenge that cannot be adequately resolved by just focusing on enhancing attention processes [

7,

10].

In contemporary times, Transformer models have demonstrated exceptional competence in a diverse range of language-related tasks, encompassing text categorization, machine translation, and question-answering. Notable models in this category include BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [

11], GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) versions 1 to 3 [

12,

13], RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pre-training) [

14], and T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) [

15]. The ability of Transformer models to effectively handle significantly big capacity models has revealed their significant influence.

Moreover, the self-attention module has greatly enhanced the long-range temporal modeling capabilities of Transformers, enabling them to achieve remarkable performance in several domains, including natural language processing and vision-related tasks. Previous studies have emphasized the computational efficiency and higher convergence properties of Transformers in comparison to topologies based on RNNs. Based on the aforementioned qualities, Transformer models inherently offer a highly promising approach for the job of online action detection [

16].

Within the scope of this research article, which explores the use of transfer learning in cross-lingual sentiment analysis, the significance of transfer learning models in comprehending and representing language becomes particularly pertinent [

17,

18]. These models are well recognized for their ability to capture intricate linguistic patterns and correlations effectively. They serve as the foundation for the effort to analyze sentiment across a wide range of languages and cultures. In conclusion, by offering a thorough overview of current trends and obstacles in the area, this work seeks to close the knowledge gap and deploy AI models for cross-lingual sentiment analysis. We hope to shed light on the potential of AI-driven techniques in interpreting feelings expressed in multilingual environments by investigating the impact of transfer learning models in capturing complex linguistic patterns across languages and cultures. Furthermore, our examination of issues like language nuances and cultural variances highlights the necessity for creative fixes to improve the efficacy of cross-lingual sentiment analysis. Below are our main Research Questions and Objectives set for this review paper:

1.1. Research Questions (RQs)

What are the key stages in the evolution of AI models used for cross-lingual sentiment analysis, and how have changes in model architectures and evaluation metrics shaped the field over time?

- RQ-1.

How is the status of AI models in this field now influenced by historical advancements and theoretical bases in sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning?

- RQ-2.

What are the main obstacles and recent advances in the use of AI models for sentiment analysis using cross-lingual transfer learning approaches?

- RQ-3.

What are the implications and uses of cross-lingual sentiment analysis in various fields, and how can AI-powered methodologies influence sentiment interpretation in multilingual environments?

1.2. Research Objectives

To thoroughly examine the problems and current advances in the usage of AI models for sentiment analysis using cross-lingual transfer learning methodologies.

To examine the current challenges encountered and creative solutions produced in the application of AI models for sentiment analysis across many languages.

To give context and explanations for the theoretical basis and historical evolution of sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning.

To help readers comprehend the historical backdrop and fundamental concepts that have affected the evolution of sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning, emphasizing their importance in AI research.

To investigate the larger implications and uses of cross-lingual sentiment analysis across diverse domains, emphasizing the importance of AI-driven methodologies in a globally linked

In summary, this study aims to stimulate future research projects focused on tackling the challenges of sentiment analysis in an increasingly linked world, in addition to adding to the body of knowledge now available in natural language processing and artificial intelligence. Below are the specific contributions of the paper:

Comprehensive Analysis: Using cross-lingual transfer learning approaches, the study analyzes in detail the difficulties and recent advancements in the use of artificial intelligence models for sentiment analysis.

Contextualization and Theoretical Foundations: This study will assist readers in comprehending the theoretical foundations and historical development of sentiment analysis, cross-lingual transfer learning, and the importance of AI models by providing a contextual background and explanation of these fields.

Latest Developments and Approaches: This research contributes to the body of knowledge on state-of-the-art methods in sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning by investigating the most recent developments and innovative approaches in these domains.

Analysis of Research Methodologies and Evaluation Standards: This work analyses research methodologies and develops evaluation standards, pointing out emerging patterns and enduring problems in sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning studies and providing insightful information about the methodological strategies employed in these fields.

Consequences in Different Domains: In addition to helping to comprehend the broader implications and applications of AI-driven techniques in interpreting sentiments expressed in multilingual environments, the exploration of cross-lingual sentiment analysis implications across various fields highlights the significance of this field in the globally interconnected digital world.

1.3. Motivation and Significance

Despite the growing availability of multilingual content and the impressive performance of AI models in Natural Language Processing (NLP), there remains a significant gap in consolidated understanding of how cross-lingual transfer learning (CLTL) has transformed sentiment analysis. The need to analyze sentiment in low-resource languages, enable cross-cultural AI applications, and develop more scalable NLP pipelines has made CLTL an increasingly critical research area. This review addresses this gap by synthesizing developments across AI model architectures, transfer strategies, evaluation methods, and application domains. The motivation stems from the fragmented nature of current literature, and this study aims to serve as a comprehensive guide for researchers and practitioners navigating this complex yet promising field.

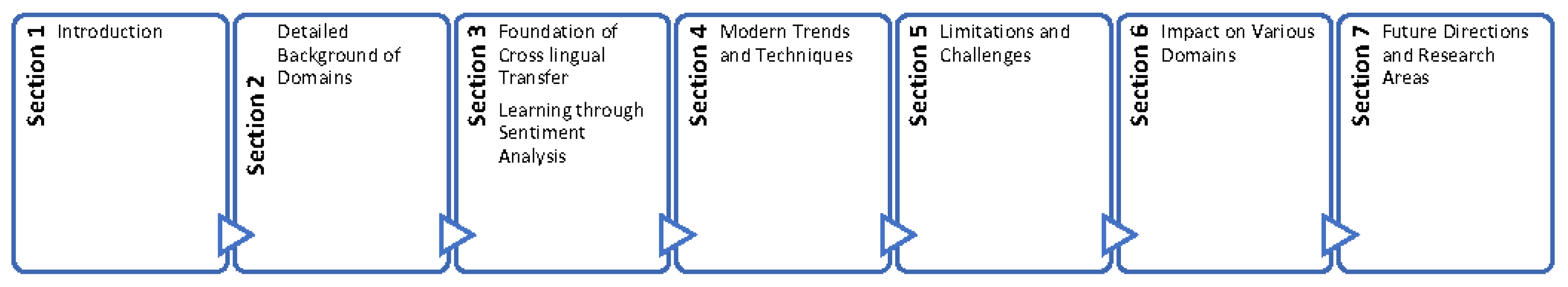

For further sections of articles,

Section 2 presents the detailed background of the domains,

Section 3 defines the foundation or basis of the cross-lingual transfer learning through sentiment analysis. Similarly,

Section 4 discusses the modern trends and techniques followed by

Section 5 presenting the challenges.

Section 6 shows the impact of this study on various domains and lastly,

Section 7 discusses the future directions and research areas. During this study, we came across several surveys and review papers but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first review that combines these three critical domains. Further, this review will provide new researchers with a place where they can find the most recent research articles between 2017-2023.

Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown of the paper structure in a graphical view.

2. Review Methodology

To ensure methodological rigor, a structured review protocol was adopted. Academic databases including IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, SpringerLink, Scopus, and Google Scholar were queried using combinations of keywords such as "cross-lingual sentiment analysis", "transfer learning", and "multilingual AI models". The search was limited to publications from 2017 to 2024.

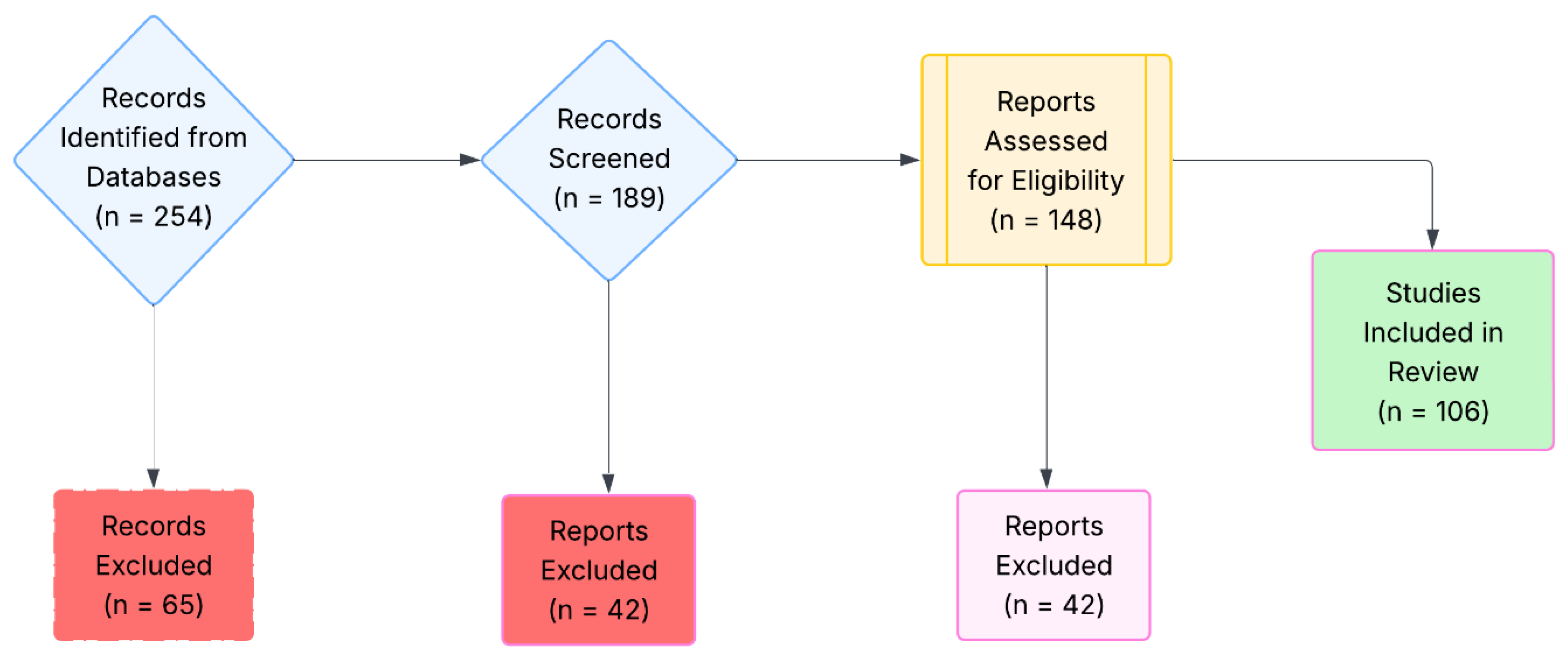

A total of 254 articles were initially retrieved. The inclusion criteria required papers to (i) involve cross-lingual or multilingual sentiment analysis, (ii) apply or evaluate AI or deep learning models, and (iii) be peer-reviewed journal or conference papers. Exclusion criteria included: opinion articles, studies focused solely on monolingual settings, or those lacking empirical validation.

After title and abstract screening, followed by full-text reviews, 106 papers were finalized. Thematic analysis was used to identify trends in model architecture, datasets, evaluation metrics, and application areas.

-

RQ-1.

“What are the key stages in the evolution of AI models used for cross-lingual sentiment analysis, and how have changes in model architectures and evaluation metrics shaped the field over time?”

3. Background and Related Work

3.1. Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis, often known as opinion mining, is an important aspect of NLP that focuses on determining the sentiment or emotional tone communicated within a particular piece of text [

19]. Its ramifications are vast, spanning sectors such as polling public opinion [

17], evaluating consumer feedback [

20], comprehending political discourse [

10], and much more.

In the corporate world, sentiment analysis is critical to understanding client feedback and sentiment towards products and services. Companies, for example, use sentiment analysis to analyze product evaluations, social media comments, and customer surveys to get insights into consumer happiness, identify problems, and make data-driven choices about product enhancements and marketing tactics [

4,

21,

22]. Attitude analysis is used in politics to evaluate public opinion and attitudes toward leaders and policies. Sentiment analysis is used by news organizations to monitor and analyze public reactions to news articles and events, allowing them to modify their reporting and coverage [

23].

The issue, however, is the global diversity of languages and dialects. Traditionally, sentiment analysis models for individual languages were constructed and fine-tuned [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. When dealing with the great linguistic diversity represented internationally, this traditional technique confronts significant obstacles. Creating distinct models for each language consumes a lot of resources and restricts the scalability of sentiment analysis systems. Furthermore, for languages with fewer resources, such as labeled datasets and pre-trained models, developing specialized sentiment analysis systems might be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible [

2,

29,

30]. For instance, below are some of the studies that applied variant transfer learning techniques on different datasets. Also,

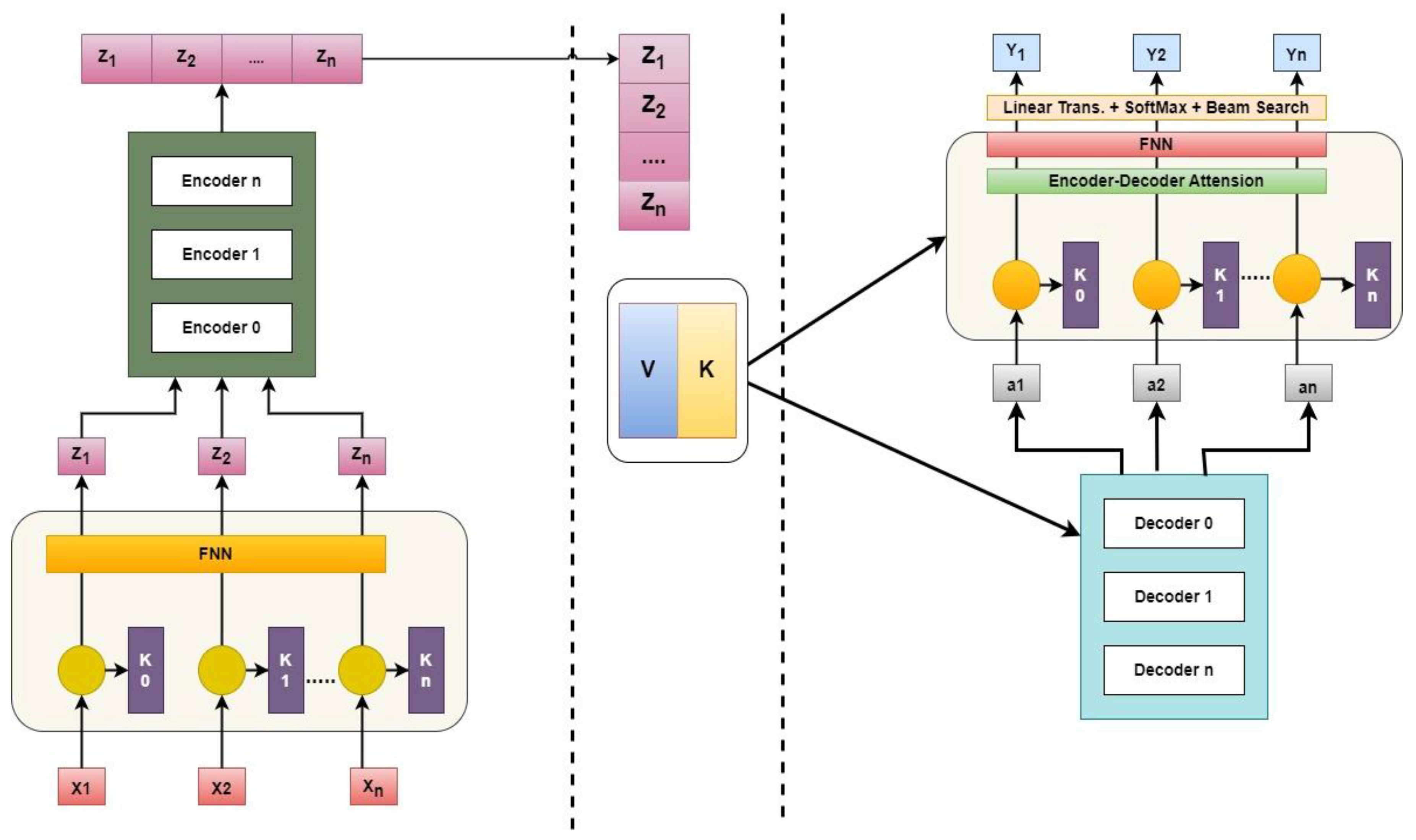

Figure 2 shows the Transformers Generalized Architecture.

3.2. Cross-Lingual Transfer Learning

The authors of the paper [

31] look at the use of transfer learning (TL) in dialectal Arabic sentiment analysis. The major goal is to improve sentiment classification performance and resolve the low resource issue with the Arabic dialect. To do this, the author applies the BERT method to convert contextual knowledge gained from the language modeling assignment into sentiment categorization. The multilingual models mBert and XLM-Roberta, the Arabic-specific models ARABERT, MARBERT, QARIB, and CAMEL, and the Moroccan dialect Darijabert are all used extensively. The performance of sentiment classification in Moroccan Arabic was shown to be greatly improved by applying TL after downstream fine-tuning studies using several Moroccan SA datasets. Nevertheless, these trials have shown that multilingual models might be more efficient in texts characterized by an intensive usage of code-switching, even though specialized Arabic models have proved to perform far better than multilingual and dialectal models.

Identifying event specifics from news articles at the sentence and token levels while considering their exquisite granularity. The author [

32] suggests a brand-new learning method based on transformers called Two-phase Transfer Learning (TTL), which enables the model to apply its knowledge from one task at one level of data granularity to another task at a different level of granularity and assesses how well it performs in sentence and token level event detection. To empirically examine, using monolingual and multilingual pre-trained transformers, language-based learning methodologies, and the suggested learning approach, how the event detection performance may be enhanced for different languages (high- and low-resource). For trials, the author employed several monolingual and multilingual pre-trained transformer models together with the multilingual version of the GLOCON gold standard dataset. Their results primarily show the usefulness of multilingual models in detecting low-resource language events. TTL can also significantly enhance model performance, depending on the order in which the tasks are learned and how closely they connect to the outcomes.Similarly, authors [

33] proposed a semi-supervised learning approach with SCL and space transfer for cross-lingual sentiment classification tasks. They used a semi-supervised learning paradigm to choose private instances from unlabeled data in the target language domain and then proposed a one-to-many mapping strategy to improve the connection of pivots between two domains. By employing unlabeled documents in the target language domain twice, this suggested model, as opposed to typical SCL-CL, recovered the valuable information lost during projection. In other words, by transferring the feature spaces using the semi-supervised learning approach, some of the useful information lost during the knowledge transfer process is regained. The efficiency of the suggested methodology has been confirmed by experimental findings using widely used product review datasets.

The transfer learning capabilities of BERT were applied by the author [

19] in 2022 to a CNN-BiLSTM deep integrated model for improved sentiment analysis decision-making. For the performance comparison of CNN-BiLSTM, the author additionally added the capability of transferring learning to traditional machine learning algorithms. The author also investigates other word embedding methods, including Word2Vec, GloVe, and fastText. then evaluate how well they performed using the BERT transfer learning approach. It manifests as a result. A cutting-edge binary classification results for sentiment analysis in Bangla that considerably surpasses all methods and embedding. The BERT scans the target text in its whole, which is a drawback. Because of this, a BERT embedding-based model outperforms other models and performs impressively in sentiment analysis tasks.

To create an Arabic task-oriented DS from start to finish, this study [

34] investigates the efficiency of cross-lingual transfer learning utilizing the mT5 transformer model. To train and test the model, the author uses the Arabic task-oriented conversation dataset (Arabic-TOD). They demonstrate how cross-lingual transfer learning was implemented using three different methods: mixed-language pre-training (MLT), cross-lingual pre-training (CPT), and mSeq2Seq. Using the same conditions, achieved good results when compared to Chinese language literature. Additionally, MLT approach-deployed cross-lingual transfer learning beats the other two techniques. Finally, we demonstrate that increasing the size of the training dataset can enhance our results. However, they employ non-domain data, which might not be entirely appropriate for the problem they are attempting to answer.

Authors in a study [

35] assess how well zero-shot transfer learning and cross-lingual contextual word embeddings perform when projecting predictions from the resource-rich English language to the resource-poor Hindi language. The English language Benchmark SemEval 2017 dataset Task 4 A is used to train and fine-tune the multilingual XLM-RoBERTa classification classifier. and then the classification model is assessed using zero-shot transfer learning on the IITP-Movie and IITP-Product review datasets, two Hindi sentence-level sentiment analysis datasets. The suggested model offers an efficient response to sentiment analysis at the phrase level (or tweet level) in a situation with limited resources. It compares favorably to state-of-the-art techniques. On both Hindi datasets, the suggested model performs well in comparison to cutting-edge methods, with an average performance accuracy of 60.93. But like other Indian languages, Hindi is also a low-resource language. Also, there is no fair comparison when the amount of training data is different between languages in the zero-shot learning scenario. Unfortunately, the author just compared the performance of the XLM-R large model to deep learning approaches; it is difficult to conclude that the XLM-R model is suitable for zero-shot scenarios.

In addition, the authors 2021 [

2] evaluated 24 papers that looked at 11 different languages and 23 different topics. The author anticipates that this tendency will continue since the observed pattern shows that there has been a consistent interest in this field. The multilingual approach appears to be losing appeal in terms of the various MSA settings. Aspect-based sentiment analysis, however, is still a little-explored area and an open research area with lots of room for future efforts. The author emphasized the key suggestions made by other writers to address the problem of the dearth of annotated data or to produce language-independent models. However, the simpler backbone made up of embeddings, a feature extractor, and a classifier look inappropriate for more complicated scenarios, notwithstanding some state-of-the-art outcomes. Additionally, there are unanswered issues such as whether embedding style best conveys the specifics of MSA.

In this article, the author [

25] covered a variety of approaches to address low-resource languages’ shortcomings in the sentiment analysis task. The author used cross-lingual embedding as a transfer learning model to model sentiment analysis. We discovered that combining training data of a low-resource language, such as Persian, with a rich-resource language, such as English, achieves excellent performance on sentiment classification also used learning methods, such as CNN and LSTM, and combinations of them, namely CNN-LSTM and LSTM-CNN, as our architectures for this task. Cross-lingual word embedding, which may be produced using a variety of methods, including sentence-aligned and word-aligned models with equivalent performance, was used to achieve these results.

Researchers may now examine public perceptions of HPV vaccinations on social media by utilizing machine learning-based methodologies that could help identify the causes behind low vaccine coverage. This is made possible by data for public sentiment analysis in social media. As a result, the author [

36] suggested three transfer-learning techniques to examine Twitter user attitudes toward HPV immunizations. 6,000 tweets were chosen at random between July 15, 2015, and August 17, 2015, and annotated using fine-tuning bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT). The outcomes demonstrated the effectiveness of the suggested strategy, which contributed to the discovery of tactics to increase vaccination uptake. The scale of data gathering presents problems, including the complexity of building huge datasets and the processing time required by conventional processing approaches, including ML and DL models.

Due to a paucity of annotated data and text processing methods, sentiment analysis research is still underdeveloped in low-resource languages like Bengali. Therefore, the author’s focus in this study [

23] is on creating resources and demonstrating the relevance of the cross-lingual method to sentiment analysis in Bengali. A thorough corpus of over 12000 Bengali reviews was produced for benchmarking. The performance of supervised machine learning (ML) classifiers in the machine-translated English corpus is also determined, and it is compared with the original Bengali corpus, to overcome the lack of standard text-processing tools in Bengali. Authors leverage resources from English via machine translation. Additionally, using Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1, the author investigates sentiment preservation in the machine-translated corpus. The author investigates lexicon-based methodologies and investigates the usefulness of using cross-domain labeled data from the resource-rich language to avoid the time-consuming data labeling procedure. Their research demonstrates that supervised ML classifiers perform similarly in Bengali and machine-translated English corpora. They attain 15%–20% better F1 scores using labeled data compared to both lexicon-based and transfer learning-based techniques. The experimental findings show that the cross-lingual strategy based on machine translation is a useful technique for Bengali sentiment categorization.

The first type of disaster domain emotion dataset in Hindi was produced by the author [

37] for this article. The author created a powerful deep-learning classifier for categorizing emotions. The classifier is underfitted since the dataset is not large enough. The author uses similar-domain big datasets in English and Hindi to transfer information and enhance the performance of our classifier to address this underfitting problem. For this, several transfer learning methodologies and cross-lingual embeddings are used. With the help of the techniques outlined in this study, classifier performance was significantly improved above baseline values. The tests demonstrate that when information is transferred between related datasets, the language of the dataset is not a barrier. They also tried our approach to determine if a classifier trained on a low-resource dataset might outperform one trained on a high-resource dataset. For this experiment, the results improved statistically significantly using this strategy. However, the authors focused on problems like the scarcity of labeled data in many interactions with the inductive transfer learning paradigm. However, this approach could not account for the categorization of emotions concerning the context in which words were used in publications.

In short, adopting cross-lingual transfer learning for sentiment analysis is motivated by the need to overcome these problems and produce more efficient and scalable solutions. Cross-lingual transfer learning adapts models learned in one language to perform sentiment analysis in another, even when labeled data for the target language is insufficient. This method uses information and patterns learned in one language to improve sentiment analysis performance in other languages.

3.3. Artificial Intelligence

3.3.1. The Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3)

The latest iteration of the Generative Pre-trained Transformer model is referred to as GPT-3 [

38]. The language model in question has the distinction of being the most expensive in terms of size, surpassing all others by a significant margin. It operates as an autoregressive language model, having undergone training with an impressive 175 billion parameters, enabling it to produce writing that closely resembles human-generated content. The findings of GPT-3 indicate that the approach of scaling up language models results in notable improvements in task-agnostic, few-shot capabilities. GPT-3 demonstrates robust performance across several natural language generation tasks, even in scenarios where gradient updates or finetuning are not employed. The accuracy rate for accurately identifying model-generated news articles, namely those with a length of 200 words, was found to be 52 percent.

Additionally, the author [

39] proposed the concept of Brilliance Bias concerning generative models. This underlying and widespread bias perpetuates the belief that intellectual genius is inherently associated with masculinity, impeding the achievements of women, even from the early stages of childhood (around ages 5-7). Furthermore, this analysis will focus on two GPT-3 models, namely the base GPT-3 model. The examination will center on the lexical items, verbs, and descriptors employed in the creation process of each model. The analysis reveals that both models have a notable tendency towards Brilliance Bias.

To assess the efficacy of individuals’ ability to deduce replies from simulated dialogues, the researcher [

40] conducted a series of empirical investigations. The sample interviews are extracted from studies that have been undertaken. The findings indicate that individuals had difficulty in reaching a consensus when tasked with choosing one out of the seven emotions that were made available for selection. It is important to emphasize that the backdrop plays a pivotal role in the situation of interviewing a child. Despite its simplicity, the single-sentence classification method fails to fulfill the requirements of its intended use case. GPT-3 exhibits positive results and applies to the use of the Communicating Child-Avatar.

In addition, the author [

41] examines three language models based on the Transformer architecture that have significant ramifications in the area. The initial model, GPT-3, stands out as the largest with a staggering 170 billion characteristics. This finding demonstrates that the size and range of a Transformer-based language model may have a significant impact, even when it is not specifically optimized for certain activities. One of the models, known as BERT, was the initial one to effectively utilize two perspectives and is currently employed by Google in its query optimization system. The XLNet model, which incorporates Transformer-XL, has demonstrated superior performance compared to BERT.

3.3.2. GPT-2

GPT-2 [

13] is an updated iteration of the GPT model (architecture in

Figure 3), which underwent training with a vast dataset sourced from 10 million websites, encompassing a total of 2.5 billion attributes. In direct comparison to GPT-2, it is evident that GPT-3 emerges as the more advantageous alternative. This model might be considered an advanced version of GPT, including a wider range of information and customizable options. In contrast to the prevailing approach of supervised learning, which relies on meticulously constructed datasets designed for specific tasks, this discovery illustrates that language models have the potential to gain information in novel areas without explicit supervision.

In this study, the authors [

42] employed an alternative method using GPT-2 medium to dynamically rectify programs. The first dataset was generated through the use of GitHub contributions. A total of 18,736 JavaScript files were utilized during the mining process. The aforementioned files are utilized in generating a total of 16,863 training examples for the GPT-2 model, thereby resulting in the identification of 1,559 potential bugs. Based on the findings of these tests, the authors conclude that despite its primary purpose of analyzing human language, GPT can acquire proficiency in software development and debugging, achieving an accuracy level of 17.25 percent.

This study [

43] investigates the textual outputs generated by deep learning models, namely the RNN and GPT-2 models, intending to provide support networks. The results indicate that the GPT-2 model has superior performance compared to the RNN model in terms of word perplexity, readability, and contextual consistency. An examination of the informational, emotional, and social support provided by individuals and GPT-2-generated responses indicated that the latter may provide a similar degree of emotional and communal support as humans, but the former may give significantly less satisfactory information.

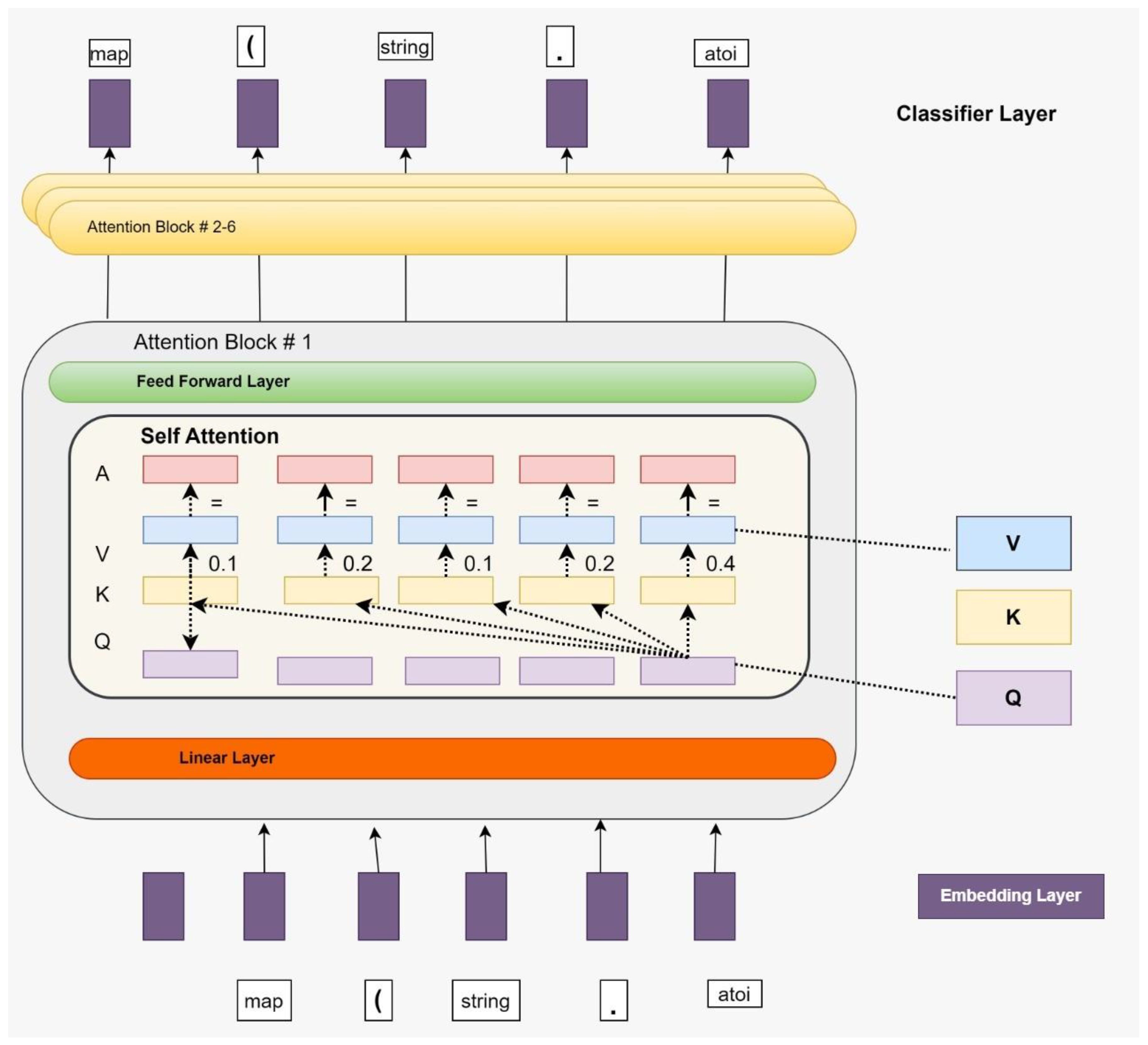

3.3.3. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

BERT is a very efficient pre-training technique utilized in the field of NLP. It relies on the analysis of contextual representations [

44]. BERT is a pioneering model that introduces a novel approach to language representation, characterized by its bidirectional and unsupervised nature, distinguishing it from previous models.

The author [

44] devised a unique model called MacBERT to address the existing barrier between the pre-trained and fine-tuned stages of the language rectification process. The job description for the Masked Language Model (MLM) has been revised to encompass the alterations made to this particular model. Furthermore, the author has created a compilation of pre-existing language models that have been trained specifically for the Chinese language. The researchers in this work conduct a subsequent round of assessment on Chinese language models that have already completed training. The author devised a unique model called MacBERT and a suite of pre-trained language frameworks in Chinese to address the existing disparity between pre-training and fine-tuning phases. Furthermore, an evaluation was conducted to assess the efficacy of Chinese pre-trained language models, including MacBERT, by subjecting them to comprehensive testing across a set of 10 Chinese natural language processing tasks. This was conducted to assess their performance level. The results obtained from the trials indicate that MacBERT has the potential to significantly enhance performance across a wide range of activities. Furthermore, a more detailed examination reveals that the MLM task demands greater attention compared to the NSP test and its variations.

The structure of word representation in deep contextualized models is examined by researchers [

45] through a systematic analysis of each layer. Subsequently, the author introduces a phrase-embedded approach that involves the dissection of BERT-based word models through a geometric study of the word representation space. The precise terminology used to refer to this approach is SBERT-WK. The current implementation of SBERTWK does not require any further instructions. The evaluation of the SBERT-WK method will encompass not only semantic textual similarity but also downstream supervised tasks. Furthermore, there are ten exploratory exercises available at the sentence level that facilitate further investigation into the subtleties of the language. The experimental results suggest that SBERT-WK exhibits a level of performance that is equivalent to state-of-the-art technology.

In a separate study, the authors [

46] utilized a pre-existing deep learning model called BERT and modified it to perform fine-grained sentiment categorization tasks specifically related to the SST dataset. Although our model had a simple downstream architecture, its performance surpassed that of models with more complex structures like recursion, repetition, and CNN. Based on the study findings, which unveiled the use of advanced contextual linguistic models like BERT, it can be argued that the process of domain adaptation in NLP has become more straightforward in contemporary times.

3.3.4. XLNet

XLNet is a language model that addresses the limitations of BERT and GPT, as highlighted in previous research [

47]. The unsupervised learning approach is based on the underlying design of Transformer-XL [

48]. According to XLNet, BERT demonstrates superior performance compared to pre-training approaches that rely on autoregressive language modeling. This may be attributed to BERT’s capability to effectively model bidirectional contexts. However, it is important to note that BERT overlooks the dependence between the masked places and instead depends on masking input as a means to enhance its performance. To overcome the limitations of BERT in this particular scenario, XLNet incorporates Transformer-XL during the pretraining phase and utilizes an autoregressive approach to acquire knowledge about bidirectional contexts by maximizing the projected likelihood.

Text classification in the context of NLP is a challenging task, particularly when dealing with shorter texts. The author [

49] presents a comparative analysis of the text classification accuracy achieved by BERT and XLNet models in comparison to typical machine learning models and methodologies, including SVM, Bernoulli naive Bayes classifiers, gaussian naive Bayes classifiers, and multinomial naive Bayes classifiers. The findings indicate that XLNet achieves a notable accuracy rate of 96 percent while classifying a dataset of 50,000 English comments.

Another research paper [

50] suggests the implementation of a sentiment classification approach in French literature. This approach combines RNN, convolutional neural networks (CNN), and multi-contextual word-based models. The model underwent training on data sourced from three distinct French databases that operate independently. We conducted a comparative analysis of several deep learning models, such as the Attention mechanism, BiLSTM, and other CNN variations, in conjunction with many words embedding modeling methodologies, including XLNet and CamemBERT. This comparison was performed with the objective of validation. The findings indicate that the combination of Autoencoder and XLNet demonstrates superior performance compared to the baseline approaches when applied to the FACR datasets. This combination achieves an effectiveness rate of 97.6 percent, showcasing its efficacy over time.

Furthermore, the author has put up the XLNet base fine-tuning technique [

24] as a means to detect bogus news in both multi-class and binary-class scenarios. The approach employed in this study involves the utilization of randomized language modeling to simultaneously gather contextual information from both the right and left contexts. Additionally, it calculates a contextualized representation of the input. The examination of the data demonstrates that the suggested fine-tuning model enhances the accuracy of false news detection algorithms for both multiclass and binary class scenarios.

In contrast, the author [

51] presents a novel methodology for sentiment analysis that categorizes textual content into predefined sentiment classes at a comprehensive textual level, taking into account entity characteristics. The recommended approach incorporates the utilization of Bi-LSTM networks to classify attributes inside online user reviews. Several research have been conducted to identify Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) by analyzing real-world datasets containing drug-related social information. These investigations aim to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed strategy utilizing several indicators. The experimental results indicate that the proposed strategy demonstrates superior performance compared to other state-of-the-art approaches that were assessed. This is achieved by improving the extraction of features from unstructured digital information, resulting in an overall increase in accuracy for sentiment classification. The proposed approach for aspect-based sentiment analysis in ADRs demonstrates a notable level of accuracy, reaching 98%, along with a commendable F1 score of 94.6%.

The author [

52] uses XLNet as a foundation to devise many algorithms to predict sentiment expressed in tweets. The accuracy of the proposed model on a benchmark dataset ranges from 90.32 to 96.45 percent, resulting in a reduction of errors by 63.32 percent.

3.3.5. Transformers

Transformer models have proven to be advantageous in several linguistic tasks, including text classification, Machine Translation (MT), and information retrieval [

9]. T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) [

15] and RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pre-training) [

14] are well-recognized as two prominent models within this particular domain.

The author of a study [

53] proposes a novel Hierarchical Graph Transformer for broad multi-label text classification. To capture the many interpretations and their interconnections inside the text, it is important to initially transform the text into a graph-based representation. To effectively capture the textual data and accurately assess the relative importance of different components, a multi-layer transformer structure with a multi-head attention mechanism is introduced. This structure incorporates word, phrase, and graph divisions, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the text’s features. To construct a comprehensive depiction of the label and establish a loss function that incorporates the semantic disparity of the label, it is imperative to use the hierarchical structure of the labels to explore the hierarchical connections among tags. Extensive testing conducted on three benchmark datasets validates that the proposed model captures the hierarchical structure and logical coherence of the text, as well as the hierarchical relationships among the labels.

Moreover, the present study [

54] aims to get a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives held by American residents about energy production. This study reveals significant disparities in the public opinion of solar and wind power at the state level, based on an analysis of 266,684 tweets collected in the year 2020. By employing RoBERTa, a state-of-the-art language model that encompasses three distinct categories, namely favorable, neutral, and negative, it is possible to achieve an accurate rate of 80%. The results obtained from our solar-specific model exhibit a high degree of similarity when compared to earlier sentiment research utilizing the BERT-based approach and employing three categories.

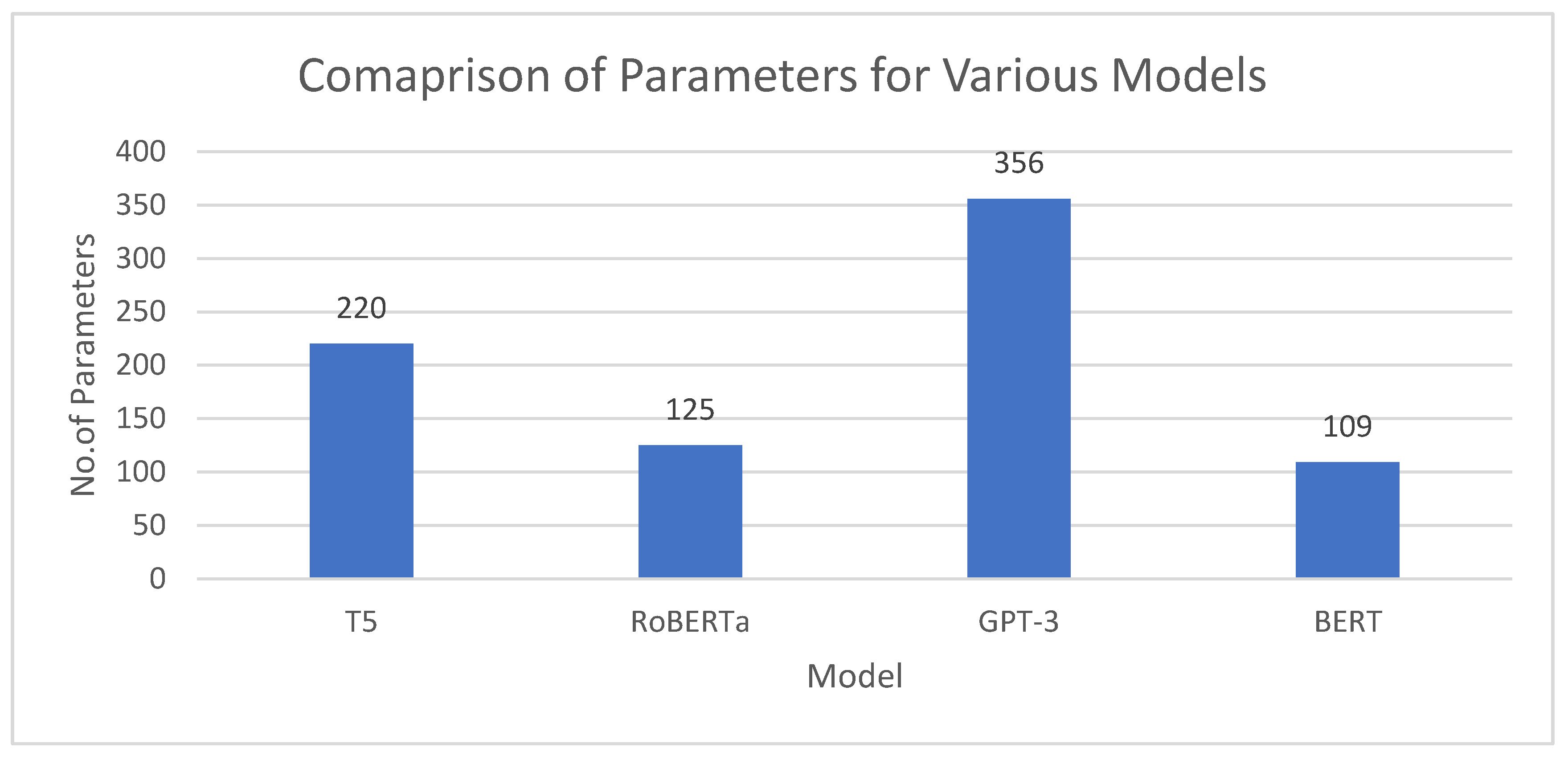

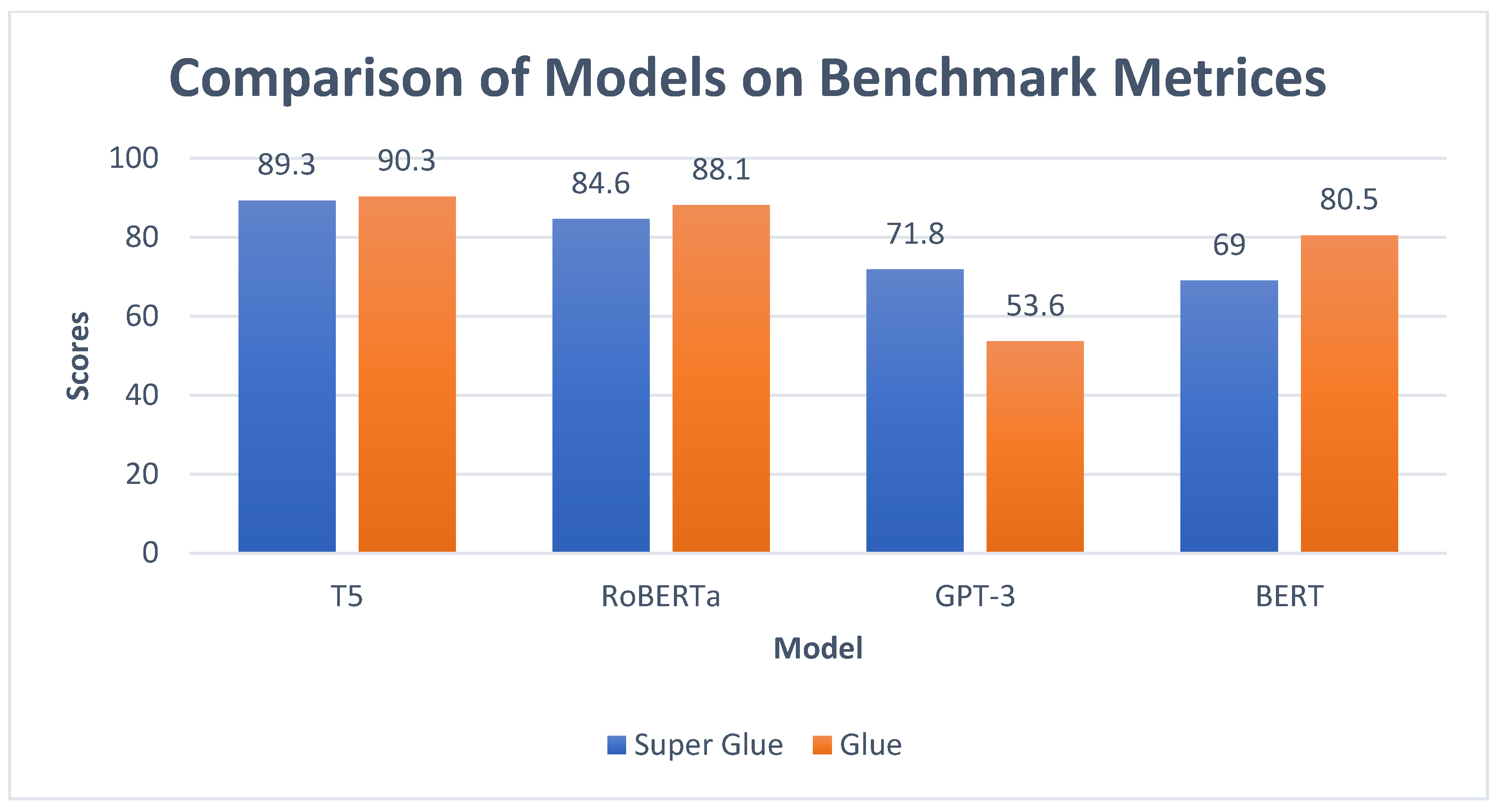

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 depict the accuracy and parameter comparison, respectively, across several models.

3.4. Discussion

The literature study in

Section 2 explores further sentiment analysis, cross-lingual transfer learning, and AI models. While it effectively emphasizes the relevance of sentiment analysis in a variety of fields, including consumer feedback evaluation and political discourse analysis, it also shows the limitations presented by linguistic diversity and a lack of labeled data in low-resource languages. However, the review may benefit from a more in-depth critical appraisal of the methodology utilized in the research addressed. For example, while cross-lingual transfer learning approaches show promise for enhancing sentiment analysis performance across languages, their effectiveness and application across diverse language pairings and domains require additional investigation. Furthermore, while the paper briefly discusses the achievements and limits of AI models such as GPT-3 and GPT-2, it does not delve further into the ethical implications of utilizing such models, such as biases and fairness concerns. Furthermore, while innovative approaches such as hierarchical graph transformers are mentioned, the study fails to address the possible obstacles and constraints of putting these sophisticated models into real-world applications, such as computing costs and scalability issues. Overall, while the literature review provides a thorough overview of the area, a more humanized discussion of methodology, constraints, and ethical issues is required in a research report to increase its comprehensiveness and thoroughness.

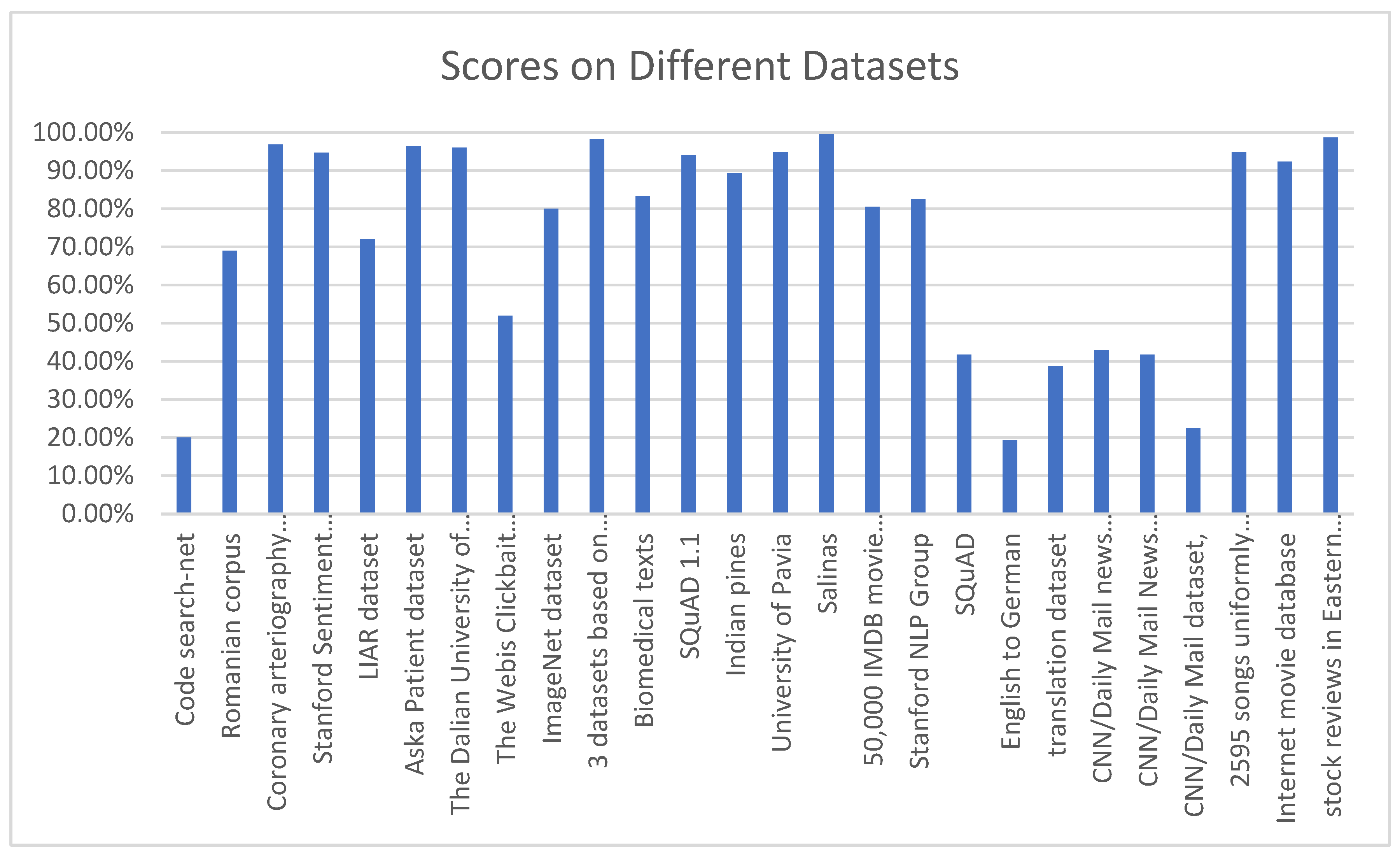

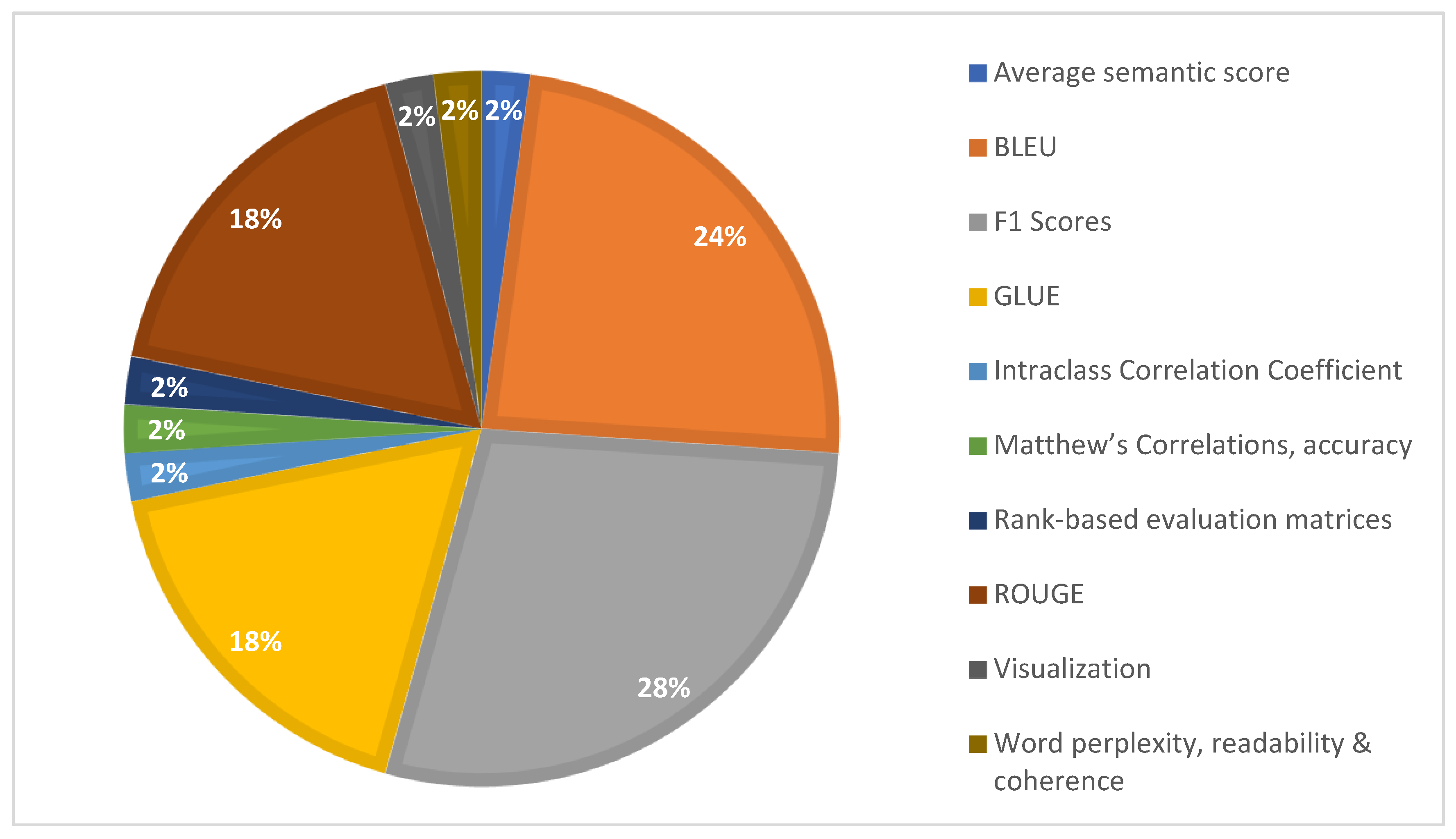

Figure 6 shows the graphical view of the performance of Transfer Learning models on datasets given in

Table 1. Similarly,

Figure 7 shows the distribution of Evaluation Metrics as counted from

Table 2.

Figure 6.

Number of Parameters Used in Various Models.

Figure 6.

Number of Parameters Used in Various Models.

Figure 7.

Scores Achieved on Different Datasets.

Figure 7.

Scores Achieved on Different Datasets.

Figure 8.

Commonly Used Evaluation Metrics.

Figure 8.

Commonly Used Evaluation Metrics.

-

RQ-2.

“How is the status of AI models in this field now influenced by historical advancements and theoretical bases in sentiment analysis and cross-lingual transfer learning?”

4. Foundations of Cross-Lingual Transfer Learning

Cross-lingual transfer learning is a derivative of the overarching principle of transfer learning, wherein a model is initially trained on a specific task or domain and subsequently leverages that acquired knowledge to address a related task or domain. Pre-trained language models have brought about a significant transformation in the field of NLP [

77,

78]. The aforementioned models, namely BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [

79], GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) [

7], and their derivatives have undergone pre-training using extensive collections of textual data in a single language. As a result, they have demonstrated exceptional proficiency across various NLP tasks, including sentiment analysis.

The utilization of pre-trained language models has facilitated the advancement of sentiment analysis models that exhibit enhanced accuracy and efficiency. These models are capable of extracting semantic and contextual information from extensive collections of text data. They may be further optimized for sentiment analysis tasks using relatively limited quantities of annotated data [

1,

51,

80,

81,

82]. Nevertheless, the primary training of these models is usually focused on a certain language, hence posing a difficulty when attempting to utilize them for languages that lack pre-existing trained models [

83].

To tackle this particular difficulty, scholars have devised methodologies for the use of cross-lingual transfer learning [

3,

84,

85,

86]. A frequently employed strategy involves the alignment of word and phrase embeddings or representations across different languages. Researchers have put forth many methodologies for acquiring bilingual word embeddings, which facilitate the mapping of words from distinct languages into a common embedding space [

87,

88]. This facilitates the transmission of information between languages by capitalizing on the similarity in word representations.

An alternative method involves employing machine translation as a means to overcome the linguistic barrier. This approach involves the translation of text from the source language to the target language, enabling the use of a pre-trained model in the source language for sentiment analysis in the target language. This methodology has demonstrated efficacy, particularly when supplemented by the process of refining and optimizing using domain-specific data in the desired language [

89,

90,

91].

Cross-lingual transfer learning signifies a fundamental change in the wider domain of transfer learning. The process entails the training of a model on a specific task or domain, followed by the transfer of the obtained knowledge to comparable activities or domains within a distinct language context. Within the domain of NLP, this particular methodology has garnered considerable interest owing to its capacity to tackle a key obstacle: the analysis of sentiment across a diverse range of languages [

33].

The emergence of pre-trained language models has had a profound impact on the field of NLP. Models such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), and their respective variations have undergone pre-training using extensive textual corpora in a monolingual context. These models can capture a substantial amount of semantic and contextual information, hence allowing them to perform very well in a wide range of NLP tasks, such as sentiment analysis [

92].

Pre-existing language models provide a notable benefit in terms of both effectiveness and precision. Remarkable performance may be achieved by fine-tuning models with very modest quantities of labeled data for certain tasks, such as sentiment analysis. Nevertheless, the inherent language-specific characteristics of these models provide a significant obstacle when attempting to utilize them in languages that lack pre-existing trained models [

93].

To surmount this particular issue, scholars have developed inventive methodologies within the field of cross-lingual transfer learning. The objective of these strategies is to facilitate sentiment analysis in languages that lack specialized pre-trained models. This allows for the use of the information contained inside pre-trained models for a distinct language [

30].

One of the primary techniques utilized in cross-lingual transfer learning is aligning embeddings or representations across different languages. The fundamental tenet posits that words or phrases possessing comparable meanings or contextual associations across distinct languages ought to exhibit analogous embeddings. This technique enables the transfer of information between languages by establishing a shared embedding space [

35]. Approaches for acquiring bilingual word embeddings have been created by researchers. These approaches facilitate the mapping of words from different languages into a single embedding space. Within this communal domain, the observable manifestations of semantic and contextual resemblances among words originating from diverse linguistic backgrounds become apparent. For example, it is probable that the term "happiness" in the English language and its corresponding counterpart in French, "bonheur," have comparable embeddings inside this same semantic domain [

87,

94,

95]. The embedding space that is shared facilitates the connection between different languages. When a sentiment analysis model that has been pre-trained in one language is presented with text in a different language, it can leverage the common embedding space to successfully comprehend and analyze sentiment. The acquisition of knowledge from the source language facilitates the ability to make well-informed predictions about sentiment in the target language.

An additional robust methodology in the field of cross-lingual sentiment research is employing machine translation as an intermediate mechanism. This approach involves the translation of text from the source language to the target language, enabling a sentiment analysis model that has been pre-trained in the source language to evaluate sentiment in the target language. The utilization of machine translation efficiently serves as a means to overcome the language barrier. For example, when a sentiment analysis model that has been trained in the English language meets content written in Spanish, it is possible to translate the Spanish text into English before doing sentiment analysis. The use of the translation process allows the model to successfully apply its pre-existing knowledge, as the analysis is performed in a language that is comprehensible to it [

91,

96].

The performance of the model may be further improved by fine-tuning it using domain-specific data in the target language. This stage is crucial in ensuring that the model effectively adjusts to the unique characteristics of emotional expression within the target language and domain. The translation process encompasses the ability to grasp subtle distinctions, informal expressions, and cultural allusions that might not be evident in the original language [

91].

In summary, cross-lingual transfer learning has emerged as a crucial approach in the domain of NLP, specifically in the context of sentiment analysis across many languages. This section discusses the inherent difficulty of utilizing pre-trained models that are exclusive to a certain language in situations where there are no dedicated resources available for other languages. Cross-lingual transfer learning enables NLP models to surpass linguistic barriers and deliver precise sentiment analysis outcomes in many linguistic environments, either by aligning embeddings or employing machine translation as an intermediary.

-

RQ-3.

“What are the main obstacles and recent advances in the use of AI models for sentiment analysis using cross-lingual transfer learning approaches?”

5. State-of-the-Art Models and Techniques

This section summarizes the state-of-the-art techniques that are commonly implied and could have futuristic scope for cross-lingual sentiment analysis.

The domain of cross-lingual sentiment analysis has experienced significant advancements, resulting in the development of several cutting-edge models and methodologies. These advancements have effectively tackled the difficulties associated with overcoming linguistic and cultural barriers, therefore enabling accurate sentiment analysis across many languages [

7].

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and its several iterations have emerged as formidable entities in the domain of NLP, showcasing remarkable proficiencies across a diverse array of tasks, encompassing sentiment analysis. The effective adaptation of BERT for cross-lingual sentiment analysis has been achieved by the utilization of its pre-trained multilingual representations by researchers. The utilization of multilingual datasets in the fine-tuning process of BERT enables sentiment analysis models to adeptly grasp the subtle intricacies inherent in many languages. Furthermore, the utilization of strategies such as translation augmentation, which involves the translation of text to and from the desired language during the training process, serves to further improve the cross-lingual capabilities of BERT-based models. These methodologies facilitate the transfer of information from BERT across other languages, leading to notable improvements in accuracy and generalization [

97].

The alignment of cross-lingual embeddings has become a crucial method in the field of cross-lingual sentiment analysis. Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and adversarial training are two methodologies employed to achieve the alignment of word embedding across different languages, intending to map them into a common embedding space. The use of this collaborative platform enables sentiment analysis models to leverage the commonalities in word representations across many languages, notwithstanding their inherent linguistic disparities. The alignment of cross-lingual embeddings enables models to consistently identify sentiment-bearing words and phrases across different languages, hence enhancing the accuracy of cross-lingual sentiment analysis [

98].

Multilingual pre-trained models have been specially designed to address the complexities associated with processing various languages. Several examples of cross-lingual language models are XLM-R (Cross-lingual Language Model with RoBERTa), mBERT (Multilingual BERT), and XLM (Cross-lingual Language Model). The models have been specifically developed with an emphasis on multi-lingually, enabling them to effectively and effortlessly process a diverse range of languages. Through the process of pre-training on vast multilingual datasets, these models develop a comprehensive comprehension of linguistic subtleties, rendering them exceptionally proficient at doing cross-lingual sentiment analysis. Furthermore, the capacity to utilize pre-existing information from a variety of languages provides a cost-efficient and data-efficient approach to doing sentiment analysis across different linguistic contexts [

99,

100].

These techniques leverage cross-lingual embeddings and concepts of transfer learning to extend the applicability of sentiment analysis models to new languages, especially in scenarios where there is a scarcity or absence of annotated data. Zero-shot learning utilizes the intrinsic connections between languages that are contained in the embeddings of the model. This enables the model to adapt to unfamiliar languages and generate meaningful sentiment predictions [

77].

Unsupervised algorithms for cross-lingual sentiment analysis propose a novel strategy to reduce dependence on annotated data. These strategies aim to minimize the reliance on a large number of labeled examples in the target languages. Frequently, researchers employ unsupervised machine translation, back-translation, and adversarial training techniques to effectively adjust models for target languages in the absence of labeled data. Unsupervised approaches enhance the capability of models to do sentiment analysis proficiently in languages with limited or absent labeled resources by creating synthetic parallel data and using cross-lingual embeddings.

Table 3 presents the list of modern techniques used in cross-lingual sentiment analysis.

Table 4 presents the common datasets, applied techniques, and languages used in cross-lingual sentiment analysis.

Table 3.

Common Models of Transfer Learning from Literature Study.

Table 3.

Common Models of Transfer Learning from Literature Study.

| Publications |

Model |

Technique |

Dataset |

Evaluation Matrix |

Results |

| [46] |

BERT |

NLP |

Stanford Sentiment Treebank (SST) |

F1 Score |

94.7% |

| [57] |

BERT |

syntax-infused Transformer, syntax-infused BERT |

WMT ’14 EN-DE dataset |

BLUE, GLUE benchmark |

BERT perform better |

| [66] |

BERT |

Sent WordNet, LR, and LSTM |

50,000 IMDB movie reviews. |

GLUE |

80.5% |

| [53] |

Transformer |

Hierarchical graph-based transformer |

3 Benchmark dataset |

Rank-based evaluation matrices |

Outperforms other deep learning models |

| [27] |

Transformer with Bi-LSTM (TRANS-BLSTM) |

BERT, Bidirectional LSTM, RNN, and transformer |

SQuAD 1.1

GLUE |

F1 score |

94:01% |

| [69] |

BERT |

LASO (Listen Attentively, and Spell Once). |

AISHELL-1 and AISHELL-2 |

Visualization |

speedup of about 50× and competitive performance |

| [70] |

BERT |

BERT-base, BERT-mix-up |

GLUE benchmark |

Matthew’s Correlations, accuracy |

BERT-mix-up outperforms |

| [24] |

XLNet |

FNN (feed-forward neural network) |

LIAR dataset |

F1 Score, Precision, Recall |

72% |

| [51] |

XLNet |

Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) |

Aska Patient dataset |

F measures |

96.4% |

| [71] |

XLNet |

Smooth Algorithm |

The Webis Clickbait Corpus (Webis-Clickbait-17) is |

F1 Scores |

52% |

| [43] |

GPT-2 |

RNN, GPT-2 |

13,850 entities of post-reply pairs |

Word perplexity, readability & coherence |

GPT-2 outperforms RNN |

| [26] |

GPT-2 |

RoGPT2 |

Romanian corpus |

BLEU |

F0.5: 69.01 |

| [72] |

GPT-2 |

NLP |

Biomedical texts |

F1 score |

3.43 |

| [73] |

GPT-2 |

SP-GPT2, GPT2-SL and GPT2-WL |

Luc-Bat dataset |

Average semantic score |

SP-GPT2 outperforms |

| [74] |

XLNet |

EXLNet-BG-Att-CNN |

The Dalian University of Technology. |

F1 Score, Precision, Recall |

96.05% |

| [40] |

GPT-3 |

Talking child avatar |

Interviews data |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

GPT-3 outperforms |

| [75] |

GPT-3 |

Codex |

Code search-net |

BLEU |

20.6 |

| [76] |

GPT-2 |

Variational RNN |

3 datasets based on BiLSTM and DistilBERT and a combination of them |

Precision, Recall, F1 scores |

98.3%, |

Table 4.

Literature of Common Techniques for Word Embedding and Transfer Learning in Cross-Lingual Sentiment Analysis.

Table 4.

Literature of Common Techniques for Word Embedding and Transfer Learning in Cross-Lingual Sentiment Analysis.

| Publication |

Technique |

Contribution |

| [101] |

GloVe |

The embedding is pre-trained by including supplementary statistical word co-occurrence data. |

| [102] |

SENTIX

|

In this study, a sentiment-aware language model (SENTIX) was pre-trained using four distinct pretraining objectives. The aim was to extract and consolidate domain-invariant sentiment information. |

| [103] |

FastText |

One potential approach to enhance the performance of word embeddings is to incorporate subword information during the pretraining phase. |

| [104] |

SOWE |

The word embedding should be pre-trained using the sentiment lexicon specific to the financial area. |

| [105] |

AEN-BERT

|

The attentional encoder network is proposed as a means to enhance the alignment between the target and context words. |

| [106] |

BERT

|

In this study, we propose to perform fine-tuning on the BERT model to improve its performance in the task of emotion detection. |

| [107] |

BERT-emotion

|

The integration of ensemble BERT with bi-LSTM and capsule models is proposed as a means to enhance the efficacy of emotion detection. |

| [108] |

BERT-Pair-QA/NLI

|

To adapt ABSA (Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis) into a sentence-pair classification task, an auxiliary sentence can be constructed. |

| [109] |

BERT-PT

|

The BERT model was fine-tuned using domain-specific review data and machine reading comprehensive data. |

| [110] |

DialogueGCN

|

This study aims to address the challenges associated with context propagation in RNNs by leveraging graph embedding techniques. |

| [111] |

DialogueRNN

|

In this study, the author analyzes and models the emotional dynamics associated with a given speech, specifically focusing on the emotional dynamic of utterance |

| [112] |

GCN

|

The adoption of a dependency tree was employed to effectively utilize structural syntactical information. |

| [113] |

HAGAN

|

The proposed approach involves the utilization of Ensemble BERT combined with hierarchical attention generative adversarial networks (GANs) to distill sentiment-distinct yet domain-indistinguishable representations. |

| [114] |

mBERT

|

BERT was pre-trained by utilizing 104 distinct language versions of Wikipedia as the foundational corpus. |

| [115] |

mBERT-SL

|

The use of the prediction outcome from mBERT as supplementary input data for the fine-tuning of a multilingual model. |

| [116] |

XLM

|

The enhancement of cross-lingual model generalization can be achieved by including supervised cross-lingual and unsupervised monolingual pretraining objectives. |

| [117] |

BAT

|

One potential approach to enhance the performance of the BERT model is to use adversarial training throughout the fine-tuning process. |

| [118] |

BERT

|

The suggestion of employing intramodality and inner-modality attention mechanisms to more effectively capture incongruent information. 28. The contribution made by this study. |

| [119] |

BERT

|

The integration of picture and text representation was enhanced by the use of an applied bridge layer and a 2D-intra-attention layer. |

| [80] |

BERT-ADA

|

The BERT model was fine-tuned using post-training techniques and further enhanced by incorporating more data from several domains. |

| [120] |

BERT-DAAT

|

Following the pretraining phase, the BERT model underwent post-training, whereby target domain masked language model tasks and a domain differentiating task were employed to extract the domain-specific features. |

| [121] |

CM-BERT

|

The application of masked multimodal attention was utilized to modify the word embedding by including non-verbal cues. |

| [122] |

HFM

|

A hierarchical fusion approach is proposed to rebuild the characteristics across three modalities. |

| [98] |

ICCN

|

The outer-product pair was utilized in conjunction with deep canonical correlation analysis to enhance the fusion of multimodal data. |

| [123] |

MAG-BERT

|

The proposed multimodal adaptation gate (MAG) is suggested as a means to enhance the incorporation of multimodal information inside a pre-trained model during the process of fine-tuning. |

| [124] |

MISA

|

The modality invariant and modality-specific mechanisms were employed to enhance the process of multimodal fusion. |

| [125] |

Multitask training- BERT

|

The performance of a multitask learning framework is significantly impacted when the learning process is asynchronous across many subtasks. |

| [126] |

SDGCN-BERT

|

The present study introduces a graph convolutional network as a means to effectively capture the interdependencies of sentiment among various characteristics. |

| [127] |

WTN

|

The utilization of an ensemble BERT model in conjunction with a Wasserstein distance module is proposed as a means to enhance the caliber of domain invariant characteristics. |

| [128] |

BERT

|

The use of an ensemble BERT model in conjunction with a contrastive learning framework is proposed as a means to augment the depiction of domain adaptation. |

| [129] |

CG-BERT

|

The context-aware information was utilized to enhance the identification of the target-aspect pair. |

| [130] |

CL-BERT

|

The application of contrastive learning was incorporated into BERT to exploit emotion polarity and patterns. |

| [131] |

CLIM

|

The integration of contrastive learning into BERT has been implemented to enhance the capture of domain-invariant and task-discriminative characteristics. |

| [132] |

Knowledge-enabled BERT

|

The utilization of external sentiment domain information was included in the BERT model. |

| [133] |

P-SUM

|

Two straightforward modules, namely parallel aggregation and hierarchical aggregation, are proposed to use the latent capabilities of hidden layers in BERT. |

| [134] |

SpanEmo

|

The emotion categorization job may be framed as a span prediction issue. |

| [135] |

SSNM

|

The interpretability of CDSA was enhanced by using both pivot and non-pivot information. |

| [136] |

BERT-AAD

|

The catastrophic forgetting issue was addressed by employing adversarial adaptation together with a distillation approach. |

| [137] |

BertMasker

|

The purpose of this study is to discover domain invariant characteristics by applying tokens that are linked to the domain and masking them. |

| [138] |

BiERU

|

The proposed Entity Recognition and Understanding (ERU) system aims to enhance the extraction of contextual compositional and emotional elements in the task of conversational emotion detection. |

| [139] |

PD-RGAT

|

The utilization of the phrase dependency graph in the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) was leveraged to effectively exploit both short and long dependencies among words. |

| [140] |

–

|

The sarcasm detection tasks were performed by directly fine-tuning several pre-trained models. |

| [141] |

-

|

Discussed the Taxonomy of Sentiment Analysis in detail. Also, proposed a mechanism for the Bombay Stock Exchange. Targeted SENSEX and NIFTY Data for classification purposes. |

Table 5.

Literature of Datasets and Methods for Cross-Lingual Domain.

Table 5.

Literature of Datasets and Methods for Cross-Lingual Domain.

| Publications |

Model |

Characteristics |

Datasets |

Languages |

| [142] |

Density-driven projection |

The process of obtaining cross-lingual clusters and transferring lexical information may be achieved through the utilization of translation dictionaries that are produced from parallel corpora. |

Google universal treebank;

Wikipedia data; Bible data;

Europarl |

MS-en / MS-de

MS-es / MS-fr

MS-it / MS-pt

MS-sv |

| [143] |

RBST |

In this study, the author represents the language disparity as a static transfer vector that exists between the source language and the destination language for each specific polarity. |

Amazon product reviews; 5 million

Chinese posts from Weibo |

en-ch |

| [144] |

Adversarial Deep Averaging Network (ADAN) |

The proposed technique for language adversarial training consists of three components: a feature extractor, a language discriminator, and a sentiment classifier. |

Yelp reviews;

Chinese hotel reviews;

BBN Arabic Sentiment

Analysis data set; |

ch-en

en-ar |

| [145] |

Attention-based CNN model with adversarial cross-lingual learning |

To address the issue of limited personal data on Sina Weibo and Twitter datasets, a potential solution is to extract language-independent characteristics. This approach aims to mitigate the problem by identifying and using traits that are not reliant on specific languages. |

Twitter;

Weibo |

en-ch

(Twitter)

en-ch

(Weibo) |

| [146] |

Bilingual-SGNS |

The SGNS algorithm is utilized to generate word embedding vectors for two languages, which are subsequently aligned to a shared space. This alignment enables the application of fine-grained aspect-level sentiment analysis. |

ABSA dataset in Hindi;

English dataset of SemEval-2014 |

en-hi |

| [147] |

BLSE |

Employ a compact bilingual dictionary and annotated sentiment data from the source language to derive a bilingual translation matrix that incorporates sentiment information. |

OpeNER;

MultiBooked dataset |

en-es

en-ca

en-EU |

| [148] |

DC-CNN |

One approach to include latent sentiment information into Cross-Lingual Word Embeddings (CLWE) involves utilizing an annotated bilingual parallel corpus. |

SST; TA; AC; SE16-T5; AFF |

en-es/ en-nl

en-ru/ en-de

en-cs/ en-it

en-fr/ en-ja |

| [149] |

Vecmap |

The unsupervised model Vecmap may be utilized to generate the first solution, hence eliminating the reliance on tiny seed dictionaries. |

Public English-Italian dataset;

Europarl; OPUS |

en-it

en-de

en-fi

en-es |

| [150] |

Ermes |

The use of emojis as an additional source of sentiment supervision data can be employed to acquire sentiment-aware representations of words. |

Amazon review dataset; Tweets |

en-ja

en-fr

en-de |

| [151] |

SVM; SNN;

BiLSTM |

To enhance the effectiveness of brief text sentiment analysis, it is recommended to modify the word order of the target language. |

OpeNER corpora;

Catalan MultiBooked dataset |

en-es

en-ca |

| [152] |

Language Invariant Sentiment Analyzer (LISA) |

The use of adversarial training across many languages with abundant resources to extrapolate sentiment information in a language with limited resources. |

Amazon Review Dataset;

Sentiraama Dataset |

en-de

en-fr

en-jp |

| [153] |

NBLR+POSwemb;

LSTM |

The use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for the initial pre-training of word embeddings, followed by a subsequent fine-tuning process. |

OpenNER;

NLP&CC 2013 CLSC |

en-es

en-ca

en-eu |

| [154] |

TL-AAE-BiGRU |

The use of Automatic Alignment Extraction (AAE) is employed to acquire bilingual parallel text and afterward align bilingual individuals inside a shared vector space through the application of a linear translation matrix. |

Product comments on Amazon |

en-ch

en-de |

| [155] |

Conditional Language Adversarial Network (CLAN) |

The model may be enhanced by the use of conditional adversarial training, which involves training both the language model and discriminator in a manner that maximizes their performance. |

Websis-CLS-10 Dataset |

en-de

en-fr

en-jp |

| [33] |

ATTM |

The training samples should be further refined. |

COAE2014 |

ch-de

ch-en

ch-fr

ch-es |

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of Existing Techniques

Contemporary models utilised in cross-lingual sentiment analysis (CLSA) exhibit a combination of encouraging potential and technical limitations. As this discipline progresses, comprehending the practical advantages and disadvantages of these models is essential for both scholarly and applied research settings.

5.1.1. Strengths

Transformer-based designs like mBERT (Multilingual BERT), XLM-R (Cross-lingual RoBERTa), and mT5 have markedly enhanced efficacy in multilingual sentiment analysis. These models get advantages from pretraining on extensive multilingual corpora, enabling them to acquire contextual embeddings that generalise effectively across languages, even in zero-shot or few-shot scenarios. Their language-agnostic representations facilitate the efficient transfer of sentiment knowledge from high-resource to low-resource languages.

Hybrid architectures (e.g., CNN-BiLSTM-BERT) augment performance by integrating the advantages of many model types: convolutional layers collect local n-gram features, BiLSTM captures long-range relationships, and BERT provide contextual embeddings. This collaboration results in enhanced precision in sentiment analysis across many topics and languages. Furthermore, CLSA models have shown useful in noisy, real-world social media messages, exhibiting resilience in multilingual online contexts.

5.1.2. Limitations

Despite their advantages, current CLSA models can entail high computational costs, necessitating robust GPUs and substantial memory, which may impede resource-limited implementations. Optimising large transformer models in many languages frequently incurs substantial training and inference expenses.

A further constraint is domain adaptability. Models developed on conventional benchmarks or general-purpose datasets sometimes encounter difficulties when applied to specialised areas like healthcare, disaster response, or finance. Linguistic subtleties, like idiomatic phrases, sarcasm, and code-switching, provide issues that existing models often mismanage, particularly in low-resource languages.

Furthermore, the absence of interpretability in deep learning-based CLSA models generates apprehensions regarding their implementation in sensitive or high-stakes contexts. The opaque nature of models such as mBERT complicates the comprehension of emotional decision-making, posing challenges for transparency, auditing, and compliance.

Despite substantial progress in the field through existing approaches, a compromise persists among performance, computing efficiency, and flexibility. Future research should concentrate on developing models that are accurate, efficient, interpretable, and adept at addressing the complete range of language and domain-specific difficulties in multilingual contexts.

In summary, the current state-of-the-art models and methodologies utilized in cross-lingual sentiment analysis represent the forefront of research in natural language processing. Researchers and practitioners are making significant advancements in the field of sentiment analysis by utilizing pre-trained language models such as BERT, cross-lingual embedding alignment, dedicated multilingual models, zero-shot learning, and innovative unsupervised methods. These approaches allow sentiment analysis to surpass linguistic barriers and offer precise insights across a wide range of languages and cultures. These technological breakthroughs exhibit considerable potential for many applications, ranging from the surveillance of global social media platforms to the analysis of international corporate data.

6. Limitations and Challenges

The limited availability of labeled data is a substantial challenge in the field of cross-lingual sentiment analysis. Pre-existing models depend on a substantial amount of annotated data to optimize their performance for certain tasks. Nevertheless, several languages suffer from a scarcity of the requisite resources essential for the efficient training of models. The phenomenon of scarcity is most evident in languages that are spoken by tiny populations or have little representation in the internet domain [

131,

152].

The restricted availability and accuracy of sentiment analysis models can be attributed to the paucity of labeled data in specific languages. Numerous solutions have been investigated by researchers and practitioners to effectively tackle this particular issue. These strategies encompass a wide range of approaches and methodologies.

6.1. Zero-Shot Learning

Zero-shot learning techniques [

35,

84,