4.1. Cost-Effectiveness

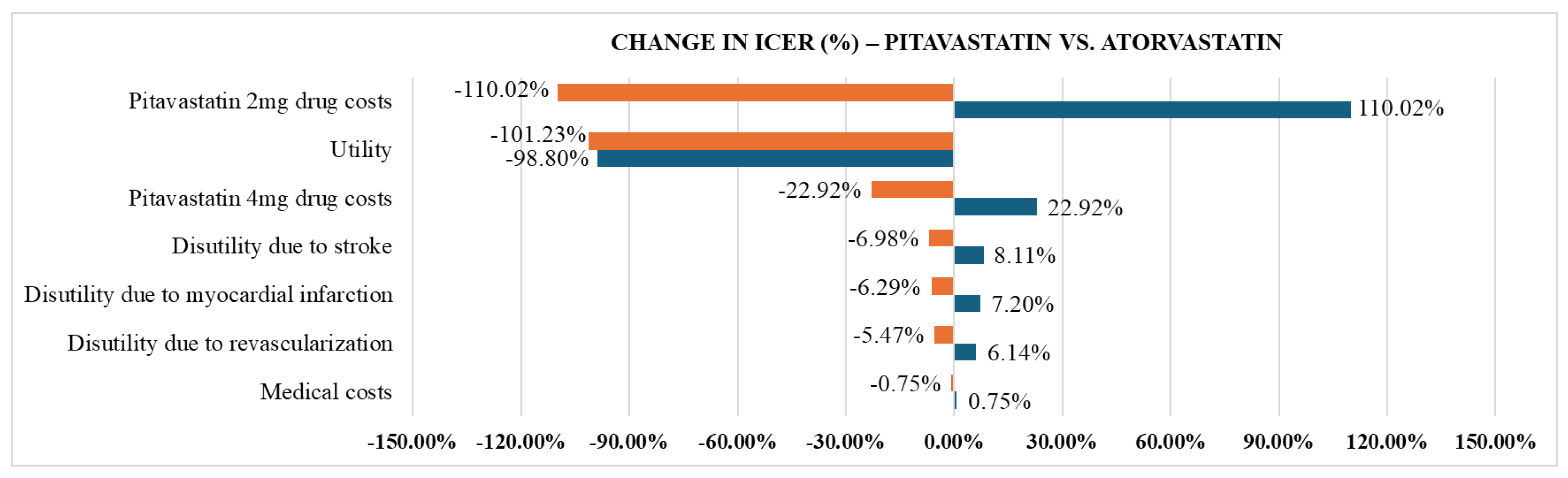

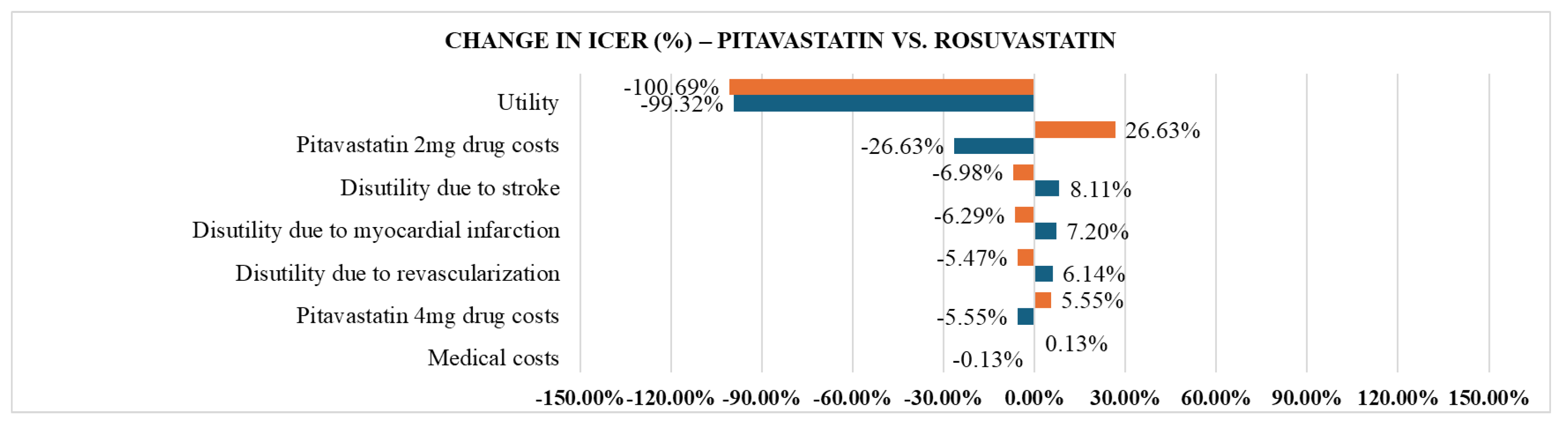

The study reveals that pitavastatin is more cost-effective than atorvastatin but more expensive than rosuvastatin over 3 months. Although pitavastatin yielded a slightly lower QALY, the difference was minor and offset by its lower cost compared to atorvastatin. In contrast, when compared to rosuvastatin, pitavastatin yielded a negative ICER (–45,868,678 VND/QALY), signifying that rosuvastatin is both more effective and less costly, thereby establishing it as the dominant strategy in the current model. The divergence in cost-effectiveness trends when comparing pitavastatin to atorvastatin versus rosuvastatin stems primarily from differences in drug pricing, a factor confirmed by one-way sensitivity analysis as having the most significant impact on ICER values. In Vietnam, rosuvastatin is widely available as a generic medication, while pitavastatin remains primarily confined to branded formulations. As a result, the price per tablet of pitavastatin is two to three times higher than that of generic rosuvastatin. Consequently, the total cost of pitavastatin treatment is more than double that of rosuvastatin.

Regarding the comparison with atorvastatin, the ICER of pitavastatin versus atorvastatin was well below Vietnam’s GDP per capita threshold (114 million VND/QALY), strengthening the conclusion that pitavastatin offers greater cost savings as a “very cost-effective” treatment option.

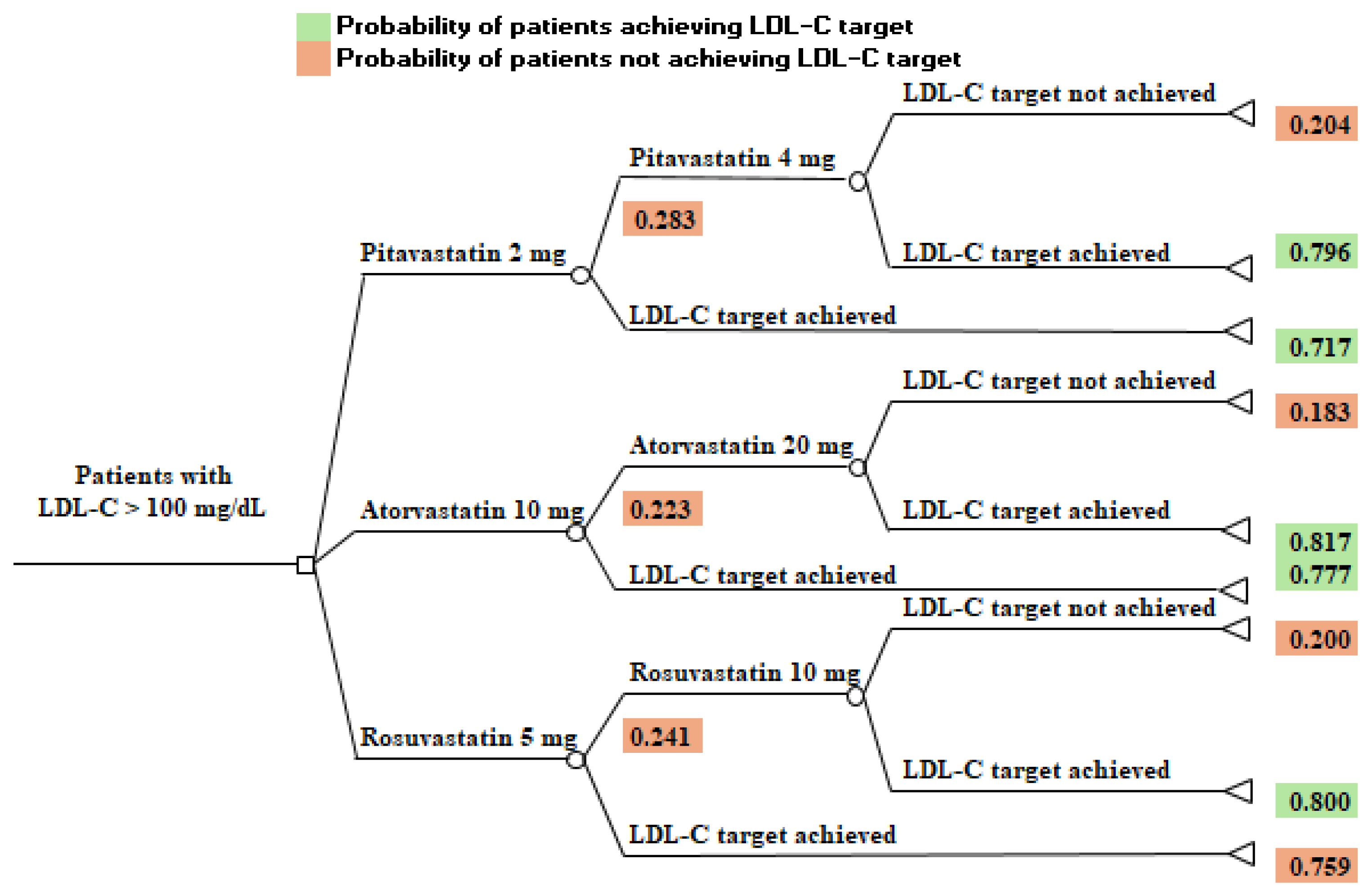

However, this conclusion holds only under the condition that the probability of achieving LDL-C targets remains high. In our study, a large proportion of patients successfully achieved LDL-C targets across all three treatment arms, with calculated rates of

94.22% for pitavastatin, 95.91% for atorvastatin, and

95.18% for rosuvastatin. While these figures are consistent with previous estimates from a systematic review in Asia (which reported LDL-C goal attainment with pitavastatin ranging from 75% to 95%) [

31]. The values reported in our model are at the

upper bound of that range, raising questions about real-world plausibility. Achieving a 95% success rate in LDL-C control would require patients to strictly adhere to the prescribed regimen throughout the entire 12-week treatment period and to sustain that adherence over the subsequent 14 years. In reality, however,

non-adherence to statin therapy is common, with many patients discontinuing treatment or missing doses, which could compromise long-term effectiveness and, consequently, the reliability of ICER projections.

Meta-analyses have revealed that adherence to statin therapy for cardiovascular disease prevention remains low, typically ranging between

50% and 60% [

32]. Even for well-established statins like atorvastatin, which have been widely circulated in healthcare systems, adherence remains suboptimal, with real-world data showing a compliance rate of only

39%, and even lower (

37%) among patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease [

33]. Notably, a large-scale 2019 study in Taiwan assessing long-term statin use in over

180,000 patients following hospital discharge demonstrated significant declines in adherence over time. While 71% of patients were considered adherent in the first six months, this rate dropped to

51% at one year, and further declined to

42% by the end of year seven [

34]. These findings underscore a substantial

gap between the modelled assumption of sustained LDL-C target attainment and real-world treatment dynamics. As a result, the

idealized ICER of pitavastatin, although favorable, may lack sufficient credibility to persuade healthcare providers or policymakers to shift from atorvastatin to pitavastatin, particularly when assessing

long-term cost-effectiveness. Not to mention, Vietnam is classified as a

lower-middle-income country [35], where the government is more likely to allocate its limited healthcare budget to address

acute conditions with immediate mortality risks, rather than invest in managing risk factors with

delayed or invisible outcomes, such as lipid control. In this context, pitavastatin is a cost-effective option, but it is not affordable to implement on a large scale in clinical practice.

However, the demonstrated cost-effectiveness of pitavastatin over atorvastatin at 12 weeks may still offer value as an alternative treatment option. Our results estimated that patients treated with pitavastatin 2 mg had around

a 71.7% chance of achieving the LDL-C target, which is similar to a Japanese study that reported a 60–70% success rate depending on cardiovascular risk levels [

36]. One notable benefit of pitavastatin is its

high tolerability, as it can avoid metabolism by CYP3A4, a common pathway for many other statins, including atorvastatin [

37]. As such, pitavastatin is especially appropriate in clinical scenarios where LDL-C lowering is

not the sole therapeutic goal, and patients require

polypharmacy to manage conditions such as

HIV [

38], impaired glucose metabolism in diabetes mellitus [

39], reducing CVD events [

40], problems with hepatic and renal function [

41]. Although transitioning to pitavastatin may slightly reduce QALY, it can save total healthcare costs and reduce the likelihood of

complications, making it an

economically reasonable choice. On the other hand, Asian populations are known to be more sensitive to statins.

Lower doses already show strong LDL-C lowering; however, at the same time, patients are at a

higher risk of musculoskeletal

side effects [42]. Based on these findings, our analysis can give clinicians and healthcare specialists a

viable option for statin-naïve individuals, particularly

older adults or those at increased risk of intolerance.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

The study employed a decision tree model to visualize the progression of health states, a strength when conducting cost–utility analysis in dyslipidemia. Unlike Markov models, the decision tree assumes a one-way progression, where each health state happens only once and does not repeat in cycles. This structure enables simplified assumptions and facilitates precise tracking of intervention effectiveness over a short-term horizon. In addition, the analysis compared pitavastatin with the two most widely used statins in clinical practice, providing clinicians with more insight into choosing the most effective statin for their patients. Regarding cost, the drug prices were taken from Vietnam’s official databases, so the cost-effectiveness of pitavastatin calculated in this evaluation is relevant and applicable to the real-world healthcare context.

On the other hand, this study has several limitations that may affect the generalizability and practical applicability of its findings. First, the analysis was limited to a 12-week time horizon. This relatively short period is insufficient to model major cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular-related mortality, or long-term maintenance treatment costs. Second, most of the input data were derived from international studies (e.g., LDL-C reduction effectiveness, utility weights, and complication probabilities). In contrast, local data from Vietnam remain limited, particularly in terms of cost profiles and patient quality of life. Differences in population characteristics, treatment conditions, and the healthcare system may result in model outcomes that do not accurately reflect real-world clinical practice in Vietnam. Additionally, this study focused solely on direct costs and did not account for indirect costs, such as productivity loss or other societal expenses. These limitations underscore the need for future research that is designed with a longer time horizon and incorporates better integration of real-world Vietnamese data and comprehensive health economic analysis, in order to enhance the reliability and applicability of findings for pharmaceutical policymaking and clinical practice.