1. Introduction

The skin's primary function as a barrier is executed by the stratum corneum, a resilient layer of flattened, anucleated corneocytes embedded in a lipid-rich matrix. This structure has long been conceptualized by the "bricks and mortar" model, which, while valuable, does not fully capture the dynamic cellular transformations that precede it. The transition from a living granular keratinocyte to a dead corneocyte—a specialized form of programmed cell death now termed corneoptosis [1,2]—is a rapid and highly orchestrated process initiated by a prolonged elevation of intracellular calcium followed by abrupt intracellular acidification [1]. It involves massive cytoplasmic reorganization, marked by the sudden appearance and disappearance of large, electron-dense structures known as keratohyalin granules (KGs) [3,4]. For decades, the function of KGs and the mechanism of their swift assembly and disassembly remained a puzzle.

At the same time, a primary defect in the epithelial barrier has long been implicated in atopic diseases. This link was strikingly confirmed in 2006 by two landmark studies showing that common, loss-of-function variants in the gene encoding Filaggrin (FLG), the major component of KGs, are the direct cause of the common dry skin condition, ichthyosis vulgaris (IV), and represent the most significant known genetic predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis (AD) [5,6]. These null mutations, carried by up to 9% of people of European origin, confer an exceptionally high risk for developing AD, establishing an unequivocal link between an epidermal structural protein and the pathogenesis of complex inflammatory disease. This discovery provided strong support for the "outside-in" hypothesis, where a primary barrier impairment allows for enhanced allergen entry, initiating downstream immune dysregulation and the subsequent "atopic march" to asthma and other allergies [5,7].

Recent advances in cell biology have revealed that many membraneless organelles, like KGs, are in fact biomolecular condensates formed via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [8]. This physical process, driven by multivalent interactions between macromolecules, provides a powerful framework for understanding how cells can rapidly and reversibly compartmentalize their cytoplasm. Here, we synthesize genetic, cell biological, and biophysical evidence to propose a new paradigm: that the formation, function, and pathology of the epidermal barrier are fundamentally driven by the principles of LLPS. We will argue that KGs are dynamic, liquid-like condensates whose lifecycle orchestrates terminal differentiation [9,10]. Crucially, we will integrate this structural pathway with the discovery of a parallel, LLPS-dependent signaling axis involving the kinase RIPK4, which co-regulates differentiation [11]. Finally, we will reinterpret the genetic basis of AD, IV, and the developmental disorder Bartsocas-Papas syndrome as diseases of aberrant phase transitions.

2. A Primer on Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biology

LLPS is a physical process by which a homogenous solution of macromolecules demixes into two coexisting phases: a dense, polymer-rich phase and a dilute, polymer-poor phase [12]. This realization has spurred major efforts to delineate the function of these 'biomolecular condensates' and has highlighted the need for rigorous experimental standards to characterize them both in vitro and in cells [13]. The primary molecular drivers of biological LLPS are intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and other multivalent macromolecules. Unlike globular proteins, IDPs lack a stable tertiary structure. According to the charge-hydrophobicity model, IDPs are distinguished by a unique combination of low mean hydrophobicity and high net charge, which prevents them from collapsing into a single folded state under physiological conditions [14]. This conformational heterogeneity allows them to act as flexible polymers, whose behavior can be described by established physical theories.

From a polymer physics perspective, LLPS is understood as the demixing of a polymer solution. The key determinant is solvent quality. For many aggregation-prone IDPs, the aqueous cellular milieu acts as a "poor solvent," meaning that interactions between polymer segments (chain-chain) are more favorable than interactions with water (chain-solvent) [15]. The thermodynamics of this process for simple polymers is described by the classic Flory-Huggins theory [16], while for charged polymers, it is extended by theories of complex coacervation [17]. In this framework, aggregation can lead to a 'polymer melt' where the chains, now surrounded by each other, act as their own solvent and approach a state of maximal conformational disorder, a concept demonstrated for the elastomeric protein elastin [18].

The interactions that mediate LLPS are multivalent and hierarchical. This has led to the useful scaffold-client framework, where multivalent "scaffolds" drive the phase separation, while "clients," which may lack this ability on their own, are recruited into the condensate and contribute to its function [8,13]. Importantly, cells can actively tune phase transitions through multiple regulatory mechanisms, including post-translational modifications (PTMs) and changes in the ionic environment [19]. The resulting condensates can adopt diverse structures, from simple liquid droplets to complex, multiphasic, or even hollow vesicle-like compartments [20].

This mechanism is a conserved strategy for creating high-performance biomaterials. Spider silk, for example, relies on a similar principle. Recombinantly produced spidroins (spider silk proteins) undergo LLPS to form liquid-like coacervate droplets, a process often initiated by dehydration at an air-water interface. This liquid intermediate state is crucial for the subsequent conformational conversion of the protein into highly ordered, β-sheet-rich structures that crystallize to form the final, exceptionally tough silk fiber [21]. Thus, in both skin and silk, LLPS serves as a vital intermediate step, concentrating and organizing disordered proteins in preparation for their assembly into a functional, solid-state material.

3. The Architects of the Granular Layer and Beyond

3.1. The Filaggrin Family: Master Scaffolds for LLPS

The proteins that form the large granules of stratifying epithelia belong to the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC), a gene cluster rich in S100-fused type proteins [2,22]. Human filaggrin is synthesized as a massive, insoluble polyprotein precursor, profilaggrin (>400 kDa), which is the primary constituent of KGs [4]. The FLG gene has a unique "fused-gene" structure, with a large central exon encoding 10-12 tandem, near-identical filaggrin repeats flanked by N- and C-terminal domains [7]. This genetic architecture is complex, featuring intragenic copy number variation (CNV) that results in individuals having between 10 and 12 filaggrin repeats per allele. This CNV itself contributes to eczema risk in a dose-dependent manner, independent of null mutations [7]. Bioinformatic analysis reveals that FLG and its paralogs are quintessential IDPs, enriched in disorder-promoting residues like glycine and serine and sharing compositional biases that favor LLPS [9,23]. This disordered nature is critical for preventing the formation of rigid, amyloid-like structures [18,24].

This architectural theme is conserved in other EDC proteins. FLG paralogs like Repetin (RPTN) and Filaggrin-2 (FLG2) also form granules in the epidermis. RPTN can form distinct condensates that are immiscible with KGs, suggesting they have different material properties and functions [9]. FLG2, whose truncating mutations are linked to Peeling Skin Syndrome and AD in African Americans [25,26], appears to colocalize with FLG but may have non-overlapping roles [2]. In the inner root sheath of the hair follicle, Trichohyalin (TCHH) is the major component of Trichohyalin Granules (TGs). Like FLG, TCHH is a large, repetitive, S100-fused IDP, but it has a distinct composition rich in arginine and glutamine [2,27]. Truncating mutations in TCHH disrupt TG formation and cause Uncombable Hair Syndrome, demonstrating that LLPS-driven granule formation is a conserved mechanism across different epithelial appendages [28].

3.2. The Keratin Cytoskeleton: A Dynamic Cage

As keratinocytes enter the spinous and granular layers, they assemble a dense network of keratin intermediate filaments (K1/K10). These filaments possess large, low-complexity domains that mediate a crucial interaction with KGs. Rather than being inert bystanders, the keratin filaments actively organize the cytoplasm by "caging" the liquid-like KGs, restricting their fusion and controlling their size [9,29]. This interaction appears to be mediated by the low-complexity domains of K1/K10 binding to the surface of FLG condensates [9].

4. Keratohyalin Granules: An LLPS-Driven Lifecycle

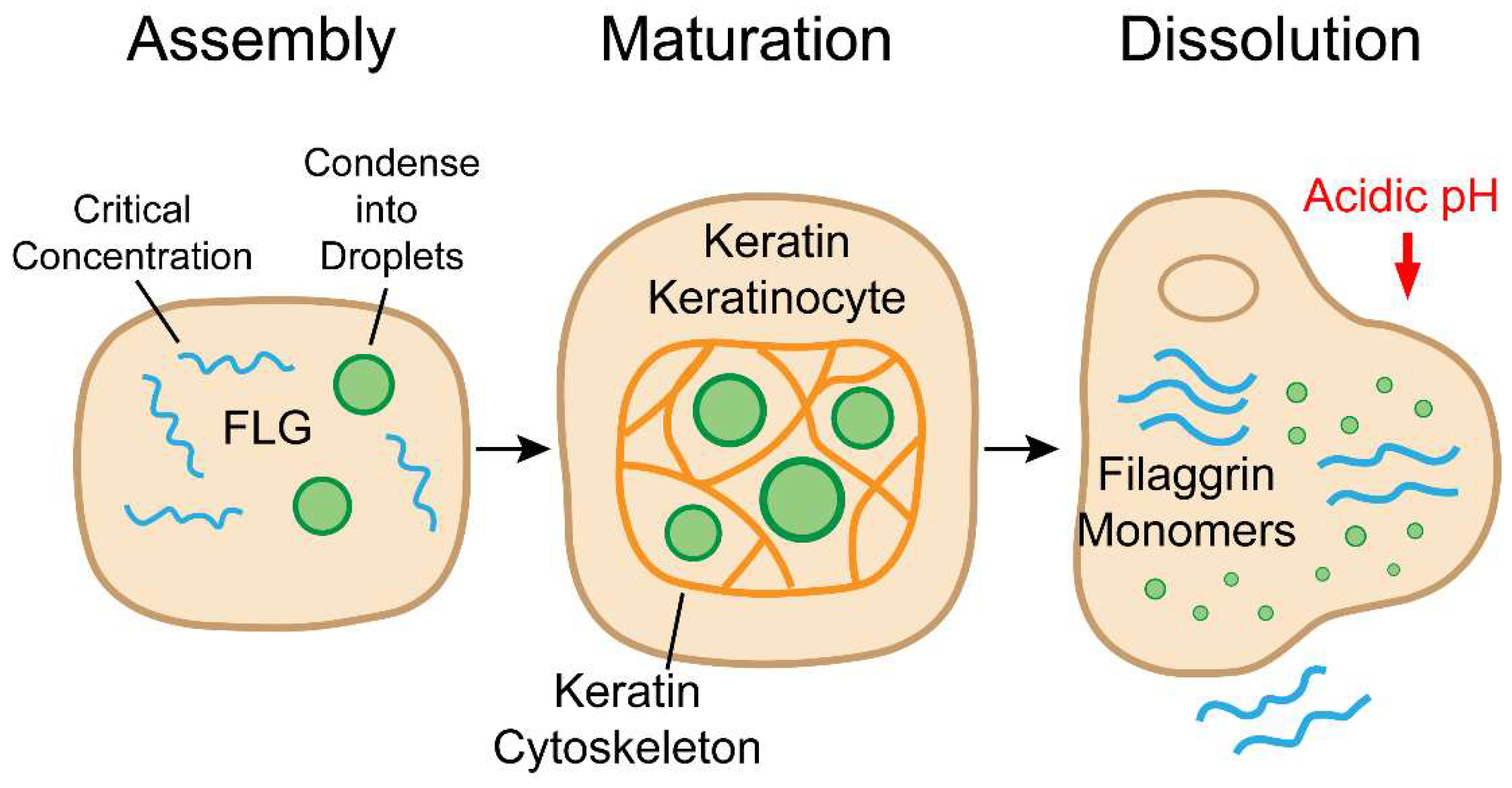

The work of Quiroz et al. (2020) provided definitive evidence that KGs are not inert aggregates but are dynamic biomolecular condensates whose entire lifecycle—assembly, maturation, and dissolution—is governed by LLPS [9] (

Figure 1).

4.1. Assembly: A Concentration- and Valency-Dependent Phase Transition

The formation of KGs is a classic example of a concentration-dependent phase transition. FLG must reach a critical concentration to trigger LLPS. This process is exquisitely sensitive to valency—the number of repeating domains. Quantitative experiments in cells showed that wild-type FLG (12 repeats) forms droplets at a critical concentration of just ~2 µM. In stark contrast, disease-associated variants with four or fewer repeats fail to phase separate under physiological conditions, with critical concentrations skyrocketing to ~130–1500 µM [9]. This provides a direct biophysical explanation for the loss of KGs in patients with severe FLG mutations.

4.2. A Crowded, Structured Liquid: Maturation and Cytoplasmic Organization

Once formed, KGs are highly dynamic, liquid-like droplets, as confirmed by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) [9]. While these observations strongly support a liquid-like state, the field emphasizes that properties such as sphericity and rapid FRAP recovery should be interpreted cautiously in the complex cellular environment and combined with evidence of concentration-dependent assembly to rigorously define a structure as a product of LLPS [13]. Live imaging in mouse skin revealed that as KGs mature, they become progressively more viscous and gel-like. This maturation is accompanied by their "caging" within the K1/K10 keratin network, which prevents runaway fusion and allows the cytoplasm to become progressively crowded [9]. This crowding exerts significant physical force, deforming the nucleus and priming it for later destruction [9,10]. This dynamic, hydrated, and disordered but cohesive state is analogous to the 'liquid structure' described for elastin, where phase separation also produces a functional biomaterial without forming a static, water-excluding core [18,30].

4.3. Dissolution: A Multimodally Regulated Switch for Corneoptosis

The final step is the abrupt dissolution of KGs as keratinocytes transition into the stratum corneum. This disassembly releases a cascade of functional molecules. The profilaggrin polyprotein is dephosphorylated and rapidly cleaved by a series of proteases into multiple monomeric filaggrin units [4]. These monomers bind to and aggregate the keratin cytoskeleton, causing the cell to collapse and flatten into a squame. Subsequently, filaggrin itself is degraded into a collection of small, hygroscopic amino acids and their derivatives, which constitute the skin's Natural Moisturizing Factor (NMF), critical for stratum corneum hydration [7]. These breakdown products also include acidic molecules like urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid, which help maintain the low pH of the stratum corneum (the "acid mantle"), providing antimicrobial defense and regulating enzymatic activity [7].

This entire process, a key step in corneoptosis, is initiated by a rapid drop in intracellular pH that follows a sustained elevation of intracellular calcium lasting approximately 60 minutes [1]. The work by Matsui et al. (2021) demonstrated that this intracellular acidification is essential for the subsequent degradation of both KGs and nuclear DNA [1]. The high histidine content of FLG acts as a pH sensor; acidification protonates these residues, disrupting the condensate and making the profilaggrin accessible to processing enzymes [9]. This LLPS-centric view suggests a refined model for the multimodal regulation of KG dissolution [2,10]. The S100 domain, which promotes the initial LLPS, is likely cleaved early after KG formation to maintain the granule's liquidity [9]. Later, at the granular-to-corneum transition, the pH drop acts as the primary trigger, but is likely followed by PTMs, such as phosphorylation, which further drive disassembly and prevent premature re-aggregation [2]. Finally, pH-activated proteases like SASPase can begin processing the now-accessible FLG scaffold [1].

Figure 1.

The Lifecycle of Keratohyalin Granules (KGs) Driven by LLPS. Keratohyalin granules (KGs) in granular keratinocytes undergo a dynamic, three-stage lifecycle orchestrated by liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). (a) Upon reaching a critical concentration, intrinsically disordered filaggrin (FLG) proteins undergo LLPS to form liquid droplets. (b) These droplets mature into more viscous condensates constrained by the keratin cytoskeleton (K1/K10), organizing the cytoplasm and priming the nucleus for destruction. (c) A drop in intracellular pH triggers dissolution of the granules, releasing FLG monomers that aggregate keratin filaments, drive cell flattening (corneoptosis), and ultimately generate natural moisturizing factor (NMF) components.

Figure 1.

The Lifecycle of Keratohyalin Granules (KGs) Driven by LLPS. Keratohyalin granules (KGs) in granular keratinocytes undergo a dynamic, three-stage lifecycle orchestrated by liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). (a) Upon reaching a critical concentration, intrinsically disordered filaggrin (FLG) proteins undergo LLPS to form liquid droplets. (b) These droplets mature into more viscous condensates constrained by the keratin cytoskeleton (K1/K10), organizing the cytoplasm and priming the nucleus for destruction. (c) A drop in intracellular pH triggers dissolution of the granules, releasing FLG monomers that aggregate keratin filaments, drive cell flattening (corneoptosis), and ultimately generate natural moisturizing factor (NMF) components.

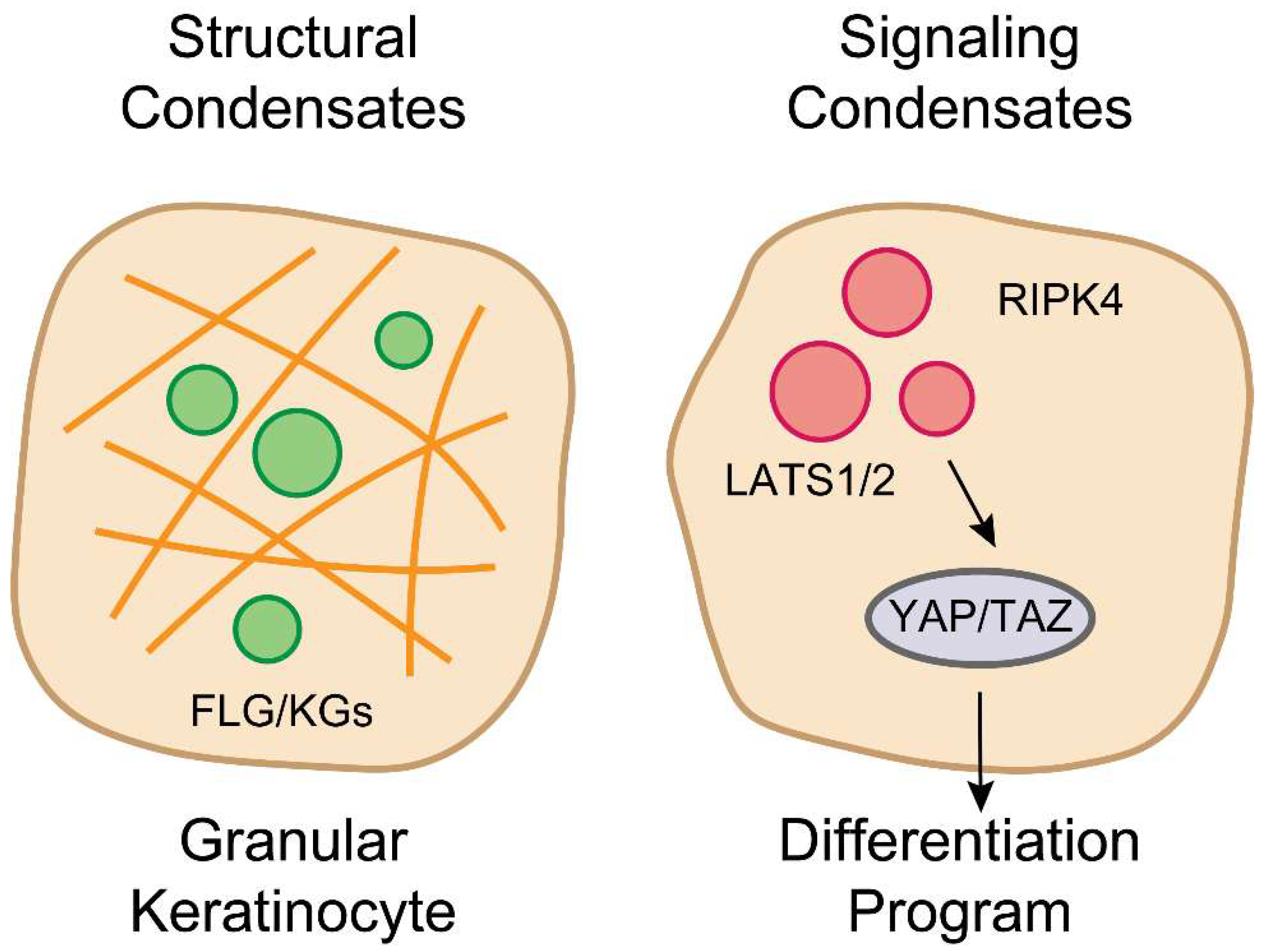

5. The RIPK4-Hippo Axis: A Parallel LLPS-Based Signaling Hub

Recent work has elucidated the precise mechanism of a parallel signaling pathway, also driven by LLPS, that is required for proper epidermal development [11]. Receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 4 (RIPK4), identified through a kinome library screen as an alternative upstream kinase of the Hippo pathway, is essential for keratinocyte differentiation.

Through its ankyrin repeat domains, RIPK4 undergoes LLPS to form signaling condensates in the cytoplasm of differentiating keratinocytes. These condensates act as hubs to recruit and concentrate the Hippo pathway kinases LATS1/2, leading to their direct phosphorylation and activation by RIPK4. This represents a non-canonical, differentiation-specific activation of the Hippo pathway. Activated LATS1/2 then inhibit the transcriptional co-activators YAP/TAZ specifically in the granular layer. While YAP/TAZ are known to promote proliferation in the basal layer [32], their RIPK4-mediated inhibition in the granular layer is necessary to suppress a proliferative program and to upregulate genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, a key lipid component of the skin barrier. This discovery reveals that the skin barrier is regulated by the interplay of at least two distinct LLPS systems: a structural system (FLG/KGs) and a signaling system (RIPK4/LATS) [11] (

Figure 2).

6. Pathophysiology: When Phase Separation Fails

The LLPS paradigm provides a powerful biophysical explanation for the molecular genetics of common and rare skin barrier diseases.

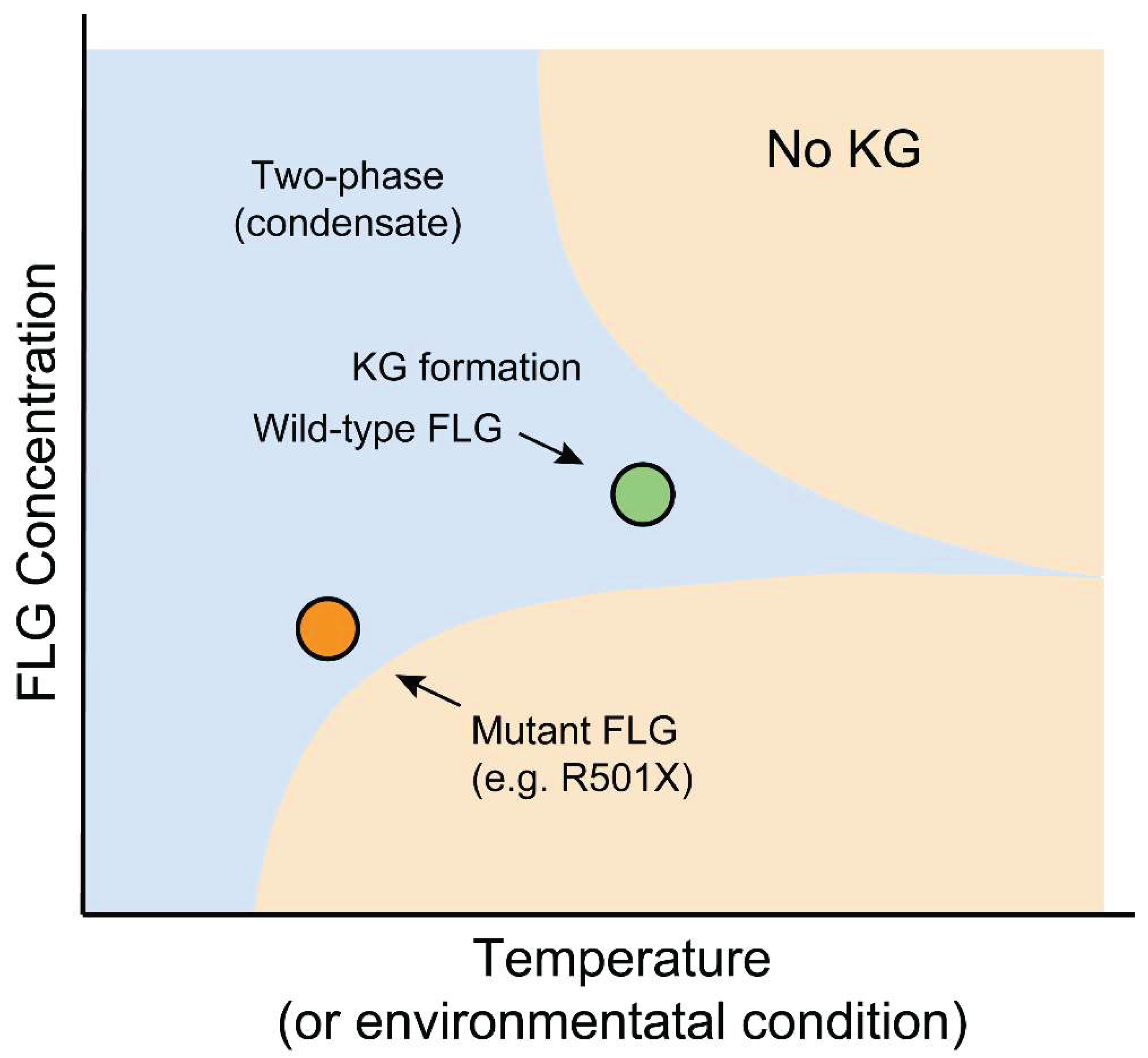

6.1. Atopic Dermatitis and Ichthyosis Vulgaris: Diseases of Altered Critical Concentration

The discovery that common loss-of-function mutations in FLG are the primary cause of IV and the strongest known genetic risk factor for AD was a watershed moment [5,6]. From an LLPS perspective, these genetic findings have clear biophysical consequences. Severely truncating mutations dramatically reduce FLG's multivalency, elevating the critical concentration for phase separation to a point where KGs fail to form [9]. However, the story is more nuanced. Milder mutations, such as those deleting the C-terminal tail, do not abolish KG formation but significantly decrease the viscosity of the resulting condensates. These less-viscous KGs "wet" the nuclear surface rather than deforming it, suggesting that the specific material properties of KGs, not just their presence, are critical for proper function [9]. Therefore, AD and IV can be re-conceptualized not just as diseases of FLG absence, but as disorders of altered phase boundaries and aberrant material properties (

Figure 3).

6.2. Bartsocas-Papas Syndrome: A Disease of Defective Signaling Condensates

The principles of LLPS-driven barrier formation find a compelling parallel in other genetic syndromes. Bartsocas-Papas syndrome, a severe developmental disorder, is caused by inactivating mutations in RIPK4 [31]. Recent work has shown that disease-derived RIPK4 mutants are defective in their ability to activate LATS1/2 because they either lack kinase activity or are unable to undergo LLPS due to truncation of the ankyrin repeat domain [11]. This positions Bartsocas-Papas syndrome as a disease caused by the failure of a signaling condensate, highlighting the importance of LLPS in both structural and regulatory aspects of skin development.

7. Conclusions

The conceptual leap provided by LLPS has resolved the long-standing enigma of keratohyalin granules. Skin barrier formation is not merely a sequence of gene expression events, but a process fundamentally governed by the physical chemistry of phase separation. This process is at least twofold: structural LLPS driven by FLG organizes the cytoplasm, while signaling LLPS driven by RIPK4 co-regulates the differentiation program.

This new paradigm opens exciting avenues for future research. Four major directions stand out: First, understanding the environmental resilience of the barrier. How do external factors like temperature and humidity, which are known to exacerbate AD, directly impact the LLPS dynamics of KGs? Given that FLG exhibits temperature-sensitive phase behavior in vitro, its condensates in the outer epidermis may be exquisitely tuned to respond to environmental shifts [2]. Gene-environment interactions are critical, as studies have shown that factors like early-life cat exposure can enhance the eczema risk conferred by FLG mutations [7]. Second, dissecting the role of intracellular crowding and organelle interactions. The interplay between growing KGs, the keratin network, and membrane-bound organelles is a key area. The link between KG dissolution and organelle degradation during corneoptosis is becoming clearer, with intracellular acidification acting as a common trigger [1]. How KG-induced crowding primes these organelles for degradation remains an open question. Third, identifying the full suite of molecular modulators. The roles of PTMs, FLG paralogs (RPTN, FLG2), and other IDPs like loricrin in tuning KG phase behavior remain largely unexplored. Loricrin, for instance, is an IDP that colocalizes with KGs in human skin and could be a key client or modulator [2,33]. Furthermore, filaggrin deficiency can be acquired, as inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 can down-regulate FLG expression, creating a vicious cycle where inflammation further compromises the barrier [7]. Fourth, exploring LLPS beyond granules. The principle of phase separation may extend to other epidermal structures, such as the assembly of tight junctions [2,34].

Ultimately, understanding the precise biophysical tuning of these LLPS processes offers the potential for novel therapeutic strategies. This bio-inspired approach is already being explored in materials science for applications in drug delivery [35], wound healing [36], and skin electronics [37]. Similarly, LLPS-based biomaterials have been shown to accelerate skin repair [38]. These studies provide a powerful proof-of-concept for designing materials that can create pro-regenerative microenvironments, moving beyond simply suppressing inflammation to actively repairing the barrier at a fundamental, biophysical level. Furthermore, the relevance of LLPS in skin biology may extend beyond barrier function, with emerging evidence linking aberrant phase separation to the progression of skin cutaneous melanoma, suggesting new therapeutic targets for skin cancers [39].

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, F.Y., L., H.W., and M.D.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and W.X.; supervision, L.W. and W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 10-2 to W.X.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32470739 to L.W.), and the Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology, Ministry of Education (Grant No. KL202506).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Atopic Dermatitis |

| AFM |

Atomic Force Microscopy |

| CNV |

Copy Number Variation |

| EDC |

Epidermal Differentiation Complex |

| FLG |

Filaggrin |

| FLG2 |

Filaggrin-2 |

| FRAP |

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching |

| IDP |

Intrinsically Disordered Protein |

| IV |

Ichthyosis Vulgaris |

| KG |

Keratohyalin Granule |

| LLPS |

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation |

| NMF |

Natural Moisturizing Factor |

| PTM |

Post-Translational Modification |

| RIPK4 |

Receptor-Interacting Serine/Threonine Kinase 4 |

| RPTN |

Repetin |

| TCHH |

Trichohyalin |

| TG |

Trichohyalin Granule |

References

- Matsui, T.; Kadono-Maekubo, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuya, T.; Kido, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Kakegawa, S.; Amagai, M.; Kubo, A. A unique mode of keratinocyte death requires intracellular acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020722118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avecilla, A.R.C.; Quiroz, F.G. Cracking the Skin Barrier: Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation Shines under the Skin. JID Innov. 2021, 1, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brody, I. An ultrastructural study on the role of the keratohyalin granules in the keratinization process. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1959, 3, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandilands, A.; Sutherland, C.; Irvine, A.D.; McLean, W.H. Filaggrin in the frontline: role in skin barrier function and disease. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.N.; Irvine, A.D.; Terron-Kwiatkowski, A.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, H.; Lee, S.P.; Goudie, D.R.; Sandilands, A.; Campbell, L.E.; Smith, F.J.; et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.J.; Irvine, A.D.; Terron-Kwiatkowski, A.; Sandilands, A.; Campbell, L.E.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, H.; Evans, A.T.; Goudie, D.R.; Lewis-Jones, S.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; McLean, W.H.I. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz, F.G.; Fiore, V.F.; Levorse, J.; Polak, L.; Wong, E.; Pasolli, H.A.; Fuchs, E. Liquid-liquid phase separation drives skin barrier formation. Science 2020, 367, eaax9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Pelkmans, L. Liquid droplets in the skin. Science 2020, 367, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Lu, Z.; Fang, Y.; et al. RIPK4 promotes epidermal differentiation through phase separation and activation of LATS1/2. Dev. Cell 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, C.P.; Eckmann, C.R.; Courson, D.S.; Rybarska, A.; Hoege, C.; Gharakhani, J.; Jülicher, F.; Hyman, A.A. Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science 2009, 324, 1729–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uversky, V.N.; Gillespie, J.R.; Fink, A.L. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins 2000, 41, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.V.; Wang, X.; Vitalis, A.; Crick, S.L. A polymer physics perspective on driving forces and mechanisms for protein aggregation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 469, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flory, P.J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne, C.P.; Tompa, P.; Pappu, R.V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, S.; Pomès, R. The liquid structure of elastin. eLife 2017, 6, e26526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söding, J.; Zwicker, D.; Sohrabi-Jahromi, S.; Boehning, M.; Kirschbaum, J. Phosphorylation as a switch for the all-or-none formation of membraneless organelles. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Hong, Y.; Najafi, S.; et al. Spontaneous Transition of Spherical Coacervate to Vesicle-Like Compartment. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2305978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, P.; Zemke, F.; Wagermaier, W.; Linder, M.B. Interfacial Crystallization and Supramolecular Self-Assembly of Spider Silk Inspired Protein at the Water-Air Interface. Materials 2021, 14, 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischke, D.; Korge, B.P.; Marenholz, I.; Volz, A.; Ziegler, A. Genes encoding structural proteins of epidermal cornification and S100 calcium-binding proteins form a gene complex (“epidermal differentiation complex”) on human chromosome 1q21. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1996, 106, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, F.G.; Chilkoti, A. Sequence heuristics to encode phase behaviour in intrinsically disordered protein polymers. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, S.; Baud, S.; Miao, M.; Keeley, F.W.; Pomès, R. Proline and glycine control protein self-organization into elastomeric or amyloid fibrils. Structure 2006, 14, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, J.; Sarig, O.; Godsel, L.M.; et al. Filaggrin 2 deficiency results in abnormal cell-cell adhesion in the cornified cell layers and causes peeling skin syndrome type A. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, D.J.; Gupta, J.; Apter, A.J.; et al. Filaggrin-2 variation is associated with more persistent atopic dermatitis in African American subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Kim, I.G.; Marekov, L.N.; et al. The structure of human trichohyalin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 12164–12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ü Basmanav, F.B.; Cau, L.; Tafazzoli, A.; et al. Mutations in three genes encoding proteins involved in hair shaft formation cause uncombable hair syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 1292–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Bouameur, J.E.; Bär, J.; et al. A keratin scaffold regulates epidermal barrier formation, mitochondrial lipid composition, and activity. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 211, 1057–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichheld, S.E.; Muiznieks, L.D.; Keeley, F.W.; Sharpe, S. Direct observation of structure and dynamics during phase separation of an elastomeric protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4408–E4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.; O'Sullivan, J.; Missero, C.; et al. Exome sequence identifies RIPK4 as the Bartsocas-Papas syndrome locus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, K.; Mohseni, M.; Kirak, O.; et al. Yap1 acts downstream of α-catenin to control epidermal proliferation. Cell 2011, 144, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, K.; Hohl, D.; McBride, O.W.; et al. The human loricrin gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 18060–18066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, O.; Maraspini, R.; Pombo-García, K.; et al. Phase Separation of Zonula Occludens Proteins Drives Formation of Tight Junctions. Cell 2019, 179, 923–936.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.L.; Huang, W.P.; Fang, Y.; et al. Fabrication of “Spongy Skin” on Diversified Materials Based on Surface Swelling Non-Solvent-Induced Phase Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 57783–57792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, R.; Liu, G.; et al. Phase separation-based electrospun Janus nanofibers loaded with Rana chensinensis skin peptides/silver nanoparticles for wound healing. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 109864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, Y.; Kim, D.H. Phase-separated stretchable conductive nanocomposite to reduce contact resistance of skin electronics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Neufurth, M.; Schepler, H.; et al. Liquid–liquid phase transition as a basis for novel materials for skin repair and regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2024, 12, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Pei, S.; Zhang, P.; et al. Liquid-liquid phase separation throws novel insights into treatment strategies for skin cutaneous melanoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).