1. Introduction

Maxillary transverse deficiency (MTD) is a common orthodontic condition that affects craniofacial function and aesthetics, leading to complications such as dental crowding, posterior crossbite, and compromised nasal airflow [

1]. Addressing MTD effectively requires orthopaedic expansion of the maxillary arch, particularly in adolescent and adult patients where conventional orthodontic methods may be ineffective due to increased skeletal resistance [

2,

3]. Traditional rapid palatal expansion (RPE) is a widely utilised technique for addressing MTD in growing patients [

4,

5]. The concept of RPE dates back to 1860, when Angell first demonstrated that separating the midpalatal suture could widen the maxilla. Conventional RPE appliances (tooth-borne “Haas” or hyrax expanders) became a standard for correcting MTD in growing patients [

6,

7]. By the 2000s, clinicians sought methods to expand the adult maxilla nonsurgically, directly targeting the palatal suture using miniscrews to avoid the need for Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (SARPE). Pioneering attempts at bone-anchored expansion, such as the Dresden Distractor [

1,

8], showed that miniscrews could be used to directly apply expansion forces to the palatal bones. Garib et al. (2008) [

9] and Tausche et al. (2007) [

10] reported successful “implant-supported” expansion in adults, laying the groundwork for hybrid approaches. Lee et al. (2010) [

11] introduced the term MARPE (Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion) for a device combining orthodontic miniscrews with a traditional expander to transmit forces to the basal bone [

12,

13]. MARPE has emerged as a clinically viable, non-surgical alternative to conventional rapid palatal expansion, particularly for skeletally mature patients and those in early permanent dentition [

12,

13,

14,

15]. By incorporating miniscrews that anchor expansion forces directly into the maxillary basal bone, MARPE effectively minimises undesired dentoalveolar effects (e.g. gingival recession, periodontal bone loss) while optimising skeletal expansion. Unlike conventional RPE, which relies solely on dental anchorage (first molars and premolars), MARPE appliances can be classified into two main types: bone-anchored MARPE, which derives its support exclusively from miniscrews inserted into the palatal vault, and hybrid MARPE, which combines miniscrew and dental anchorage [

15]. This difference in anchorage significantly influences the biomechanical response by altering the distribution of forces within the maxillofacial complex, thereby affecting the magnitude and pattern of skeletal expansion. Moreover, the type of cortical engagement - bicortical versus monocortical -further modulates stability and stress distribution. Bicortical anchorage, where the miniscrew engages both the palatal and nasal cortical plates, provides superior mechanical performance, reduced implant deformation, and promotes more parallel midpalatal suture separation compared to monocortical engagement, which involves only a single cortical interface [

16].

While overall clinical reports highlight high efficacy in correcting MTDs and favourable long-term stability—particularly in cases of posterior crossbite and airway improvement [

17,

18,

19] —the underlying skeletal response remains highly variable and patient-specific. Younger adults, typically with a mean age around 22 years, demonstrate higher success rates, likely due to greater sutural patency and bone plasticity [

20,

21]. Hounsfield unit measurements further support these observations: lower bone density in the middle and posterior nasal spine regions is positively associated with expansion efficiency, whereas denser anterior areas offer limited predictive value [

20]. Moreover, cortical bone thickness is a critical determinant of miniscrew stability. Thicknesses below 0.62 mm have been linked to a 41% reduction in retention rates [

22,

23]. Transient soft-tissue discomfort, pain, or inflammation may also be observed during active expansion, particularly in skeletally mature patients [

24].

While patients may experience a temporary decline in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)—primarily due to discomfort during the initial activation phase—these effects typically resolve as treatment progresses, with most individuals returning to baseline well-being [

25]. Long-term improvements in breathing, sleep quality, chewing efficiency, and speech have been documented, particularly in patients with nasal airway obstruction or obstructive sleep apnoea [

2,

14,

26]. However, asymmetric skeletal expansion occurs in up to 34% of cases, and rare but serious events such as maxillary fractures have been reported. For instance, Hanai et al. (2025) [

27] documented a fracture extending from the infraorbital foramen to the alveolar process in a patient with thin cortical bone and advanced midpalatal suture fusion. Numerical results indicate that the zygomatico-maxillary suture experiences high stress during expansion, increasing fracture risk in anatomically susceptible individuals [

27,

28].

Furthermore, other complications include dentoalveolar effects such as buccal bone thinning (0.10–0.33 mm), gingival recession, root resorption, and transient infraorbital nerve paraesthesia [

21,

27]. Hardware-related issues—miniscrew loosening (5–18.5% of cases) and expander deformation—are often linked to excessive activation forces or inadequate bicortical engagement [

20,

29]. Expander design further impacts outcomes; devices with shorter extension arms can generate forces exceeding 400 N, doubling the stress of conventional expanders and elevating complication risks [

30]. Post-adolescent patients face a nearly 10% annual increase in complication likelihood [

29].

Optimising MARPE protocols requires understanding the balance between skeletal expansion and dentoalveolar compensation, which is highly sensitive to cortical thickness, suture morphology, and appliance design [

1,

31]. In this context, the finite element method (FEM) has emerged as a valuable in-silico approach for exploring these dynamics. By reconstructing three-dimensional anatomical geometries from computed tomography (CT) or CBCT data [

4,

32,

33], FEM enables quantitative analysis of stress-strain distributions within the midpalatal suture, circummaxillary structures, and bone-implant interfaces under clinically relevant boundary conditions [

34,

35]. This capability is critical for optimising MARPE protocols, as the technique aims to maximise skeletal expansion while minimising dentoalveolar compensation—a balance highly sensitive to individual variations in cortical thickness, suture morphology, and appliance design [

13,

36].

FEM-based studies have systematically evaluated the biomechanical effects of screw placement, expander configuration, and force vectors, identifying consistent stress concentrations at the palatal suture and paraskeletal regions [

37,

38]. In addition, FEM further clarify how variables such as miniscrew geometry, cortical bone density, and constraint types influence displacement patterns, providing actionable insights for patients with advanced skeletal maturation [

39,

40]. Nevertheless, key limitations persist in translating FEM findings to clinical practice. Many models inadequately represent the viscoelastic and time-dependent behaviour of sutural tissues, overlook soft tissue contributions, or lack validation against experimental or clinical datasets—compromising their predictive accuracy [

41,

42]. Additionally, simplifications in mesh resolution and loading scenarios may obscure critical nonlinear responses, such as microdamage accumulation or sutural interdigitation effects, which are pivotal for understanding relapse mechanisms.

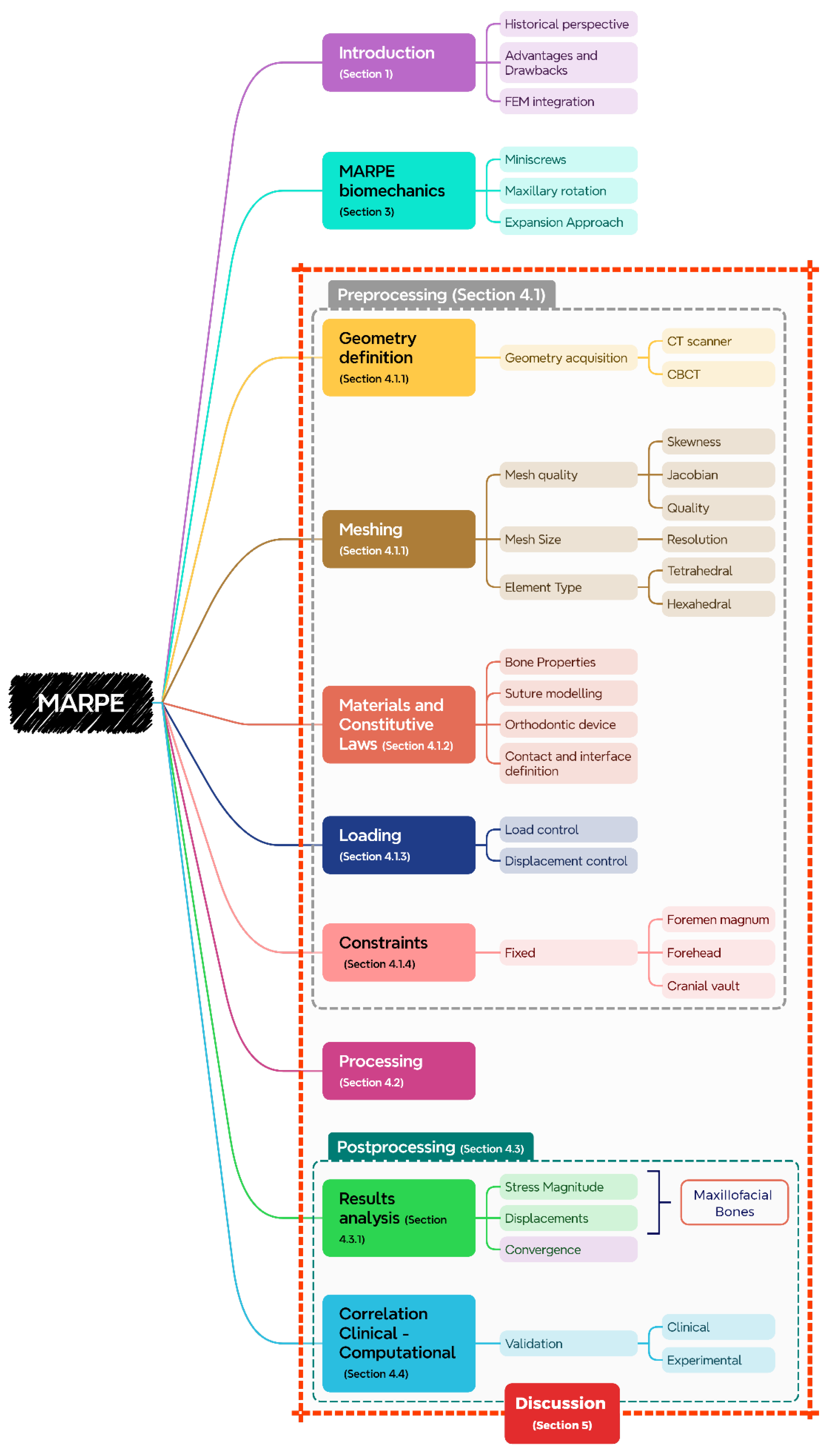

This narrative review critically evaluates the methodological rigour and translational relevance of FEM in MARPE research, with a focus on reconciling computational advancements with persistent gaps. By analysing model fidelity in anatomical reconstruction, boundary condition rationalization, contact mechanics, and validation strategies, this work highlights pathways to refine in-silico frameworks (

Figure 1). Addressing these limitations is essential for developing evidence-based, patient-tailored MARPE protocols that reliably predict long-term skeletal stability.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review utilised five primary academic databases—PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, and Semantic Scholar—supplemented by AI-assisted tools such as Elicit (Ought, Oakland, United States), STORM (Stanford University, Stanford, United States), and ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, California) search to enhance coverage. The core search strategy combined the keyword “MARPE” with the exact phrases “Finite Element Analysis” or “Finite Element Method,” and the terms “Stress” or “Strain,” ensuring a focus on both methodological and mechanical aspects of MARPE. To specifically target studies addressing mesh quality in orthodontic FEM, additional keywords such as “Orthodontics FEM implants,” “Mesh Quality,” “Skewness,” and “Aspect Ratio” were used. These terms helped identify publications discussing the reliability and numerical precision of FEM simulations involving MARPE devices.

Search queries in Elicit were framed around the research question: “How can finite element analysis (FEA) be used to model the mechanical response of a MARPE device implanted in the skull?” Emphasis was placed on extracting information about key modelling steps, including geometry creation, mesh generation, material properties, and loading conditions. In STORM, the search was driven by clinically and computationally oriented questions covering validation methodologies, critical design parameters, and common complications associated with MARPE: “What are the clinical drawbacks, complications, and unplanned maxillofacial bone changes associated with MARPE how do they impact treatment outcomes?”, “What advancements in finite element analysis methodologies could potentially address the variability in clinical outcomes associated with MARPE devices?”, “What are the main gaps currently identified in the integration of clinical data and finite element analysis (FEA) specifically for MARPE devices in orthodontics?”, “Using finite element analysis, how does Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) affect stress and strain distribution in the appliance, cranial bones, and craniofacial sutures?”

ChatGPT was used to support exploratory searches with a CIDI-based prompts [

43,

44] as follows:

Context:

"I am researching the biomechanics of Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) using finite element analysis (FEA)."

Instructions:

"I need a comprehensive, in-depth literature review on this topic."

Details:

Focus specifically on stress and strain distribution in:

the appliance

cranial bones

craniofacial sutures

Include the most recent studies (last 10 years).

Summarise key methodologies, such as:

boundary conditions

material properties

sutural modelling approaches

Highlight major findings and their biomechanical implications.

Identify research gaps or inconsistencies across the literature.

Input:

"Provide proper citations with DOI links whenever possible."

A total of 70 studies published since 2014 were reviewed. Inclusion criteria focused on works that applied FEM to MARPE or reported craniofacial biomechanical responses during expansion. 14 studies detailed FEM parameters, while only 6 included clinical data to validate computational outcomes (

Table 1).

3. MARPE Biomechanics

The biomechanics of MARPE differ fundamentally from those of conventional RPE due to the use of miniscrews, which direct forces primarily to the midpalatal suture. This configuration transmits mechanical loads through the maxillary bone rather than the dentition, thereby reducing overall craniofacial stress and producing a more favourable expansion pattern [

13,

39]. Additionally, MARPE alters the maxillary centre of rotation, shifting it from the frontomaxillary suture or superior orbital fissure to the region of the frontozygomatic suture. This difference in rotational behaviour has been associated with greater nasal cavity expansion in MARPE-treated patients [

32,

49].

The MARPE protocol often includes a two-stage, cyclic expansion approach-beginning with rapid activation followed by low-force oscillatory loading-which generates alternating tensile-compressive strains to enhance craniofacial remodelling by progressively weakening circummaxillary sutures [

29,

50]. However, the success of MARPE is closely tied to the patient’s skeletal maturity. As individuals age, particularly beyond the third decade of life, the midpalatal suture becomes increasingly interdigitated and resistant to orthopaedic forces, limiting the extent of skeletal expansion. In such cases, adjunctive procedures such as corticotomies may be necessary to overcome suture resistance and reduce the risk of complications like alveolar bone dehiscence [

14,

22,

29,

33].

Precise planning using CBCT improves positioning of expanders and miniscrews, thereby enhancing treatment efficiency and minimising adverse outcomes [

51]. Nonetheless, emerging evidence suggests that the strain levels induced by MARPE—similar to those observed in fully osseointegrated dental implants—may be insufficient to trigger substantial bone remodelling, potentially explaining the limited long-term skeletal effects reported in some studies [

52,

53,

54].

Miniscrew stability is a key determinant of MARPE success. While bicortical anchorage (engaging both palatal and nasal floors) is theorised to enhance stress distribution, current evidence does not indicate a significant advantage over mono-cortical configurations [

55]. For improved stability and force delivery, implants of at least 8 mm in length are recommended, and using four miniscrews is advised in adult patients with highly interdigitated sutures [

56].

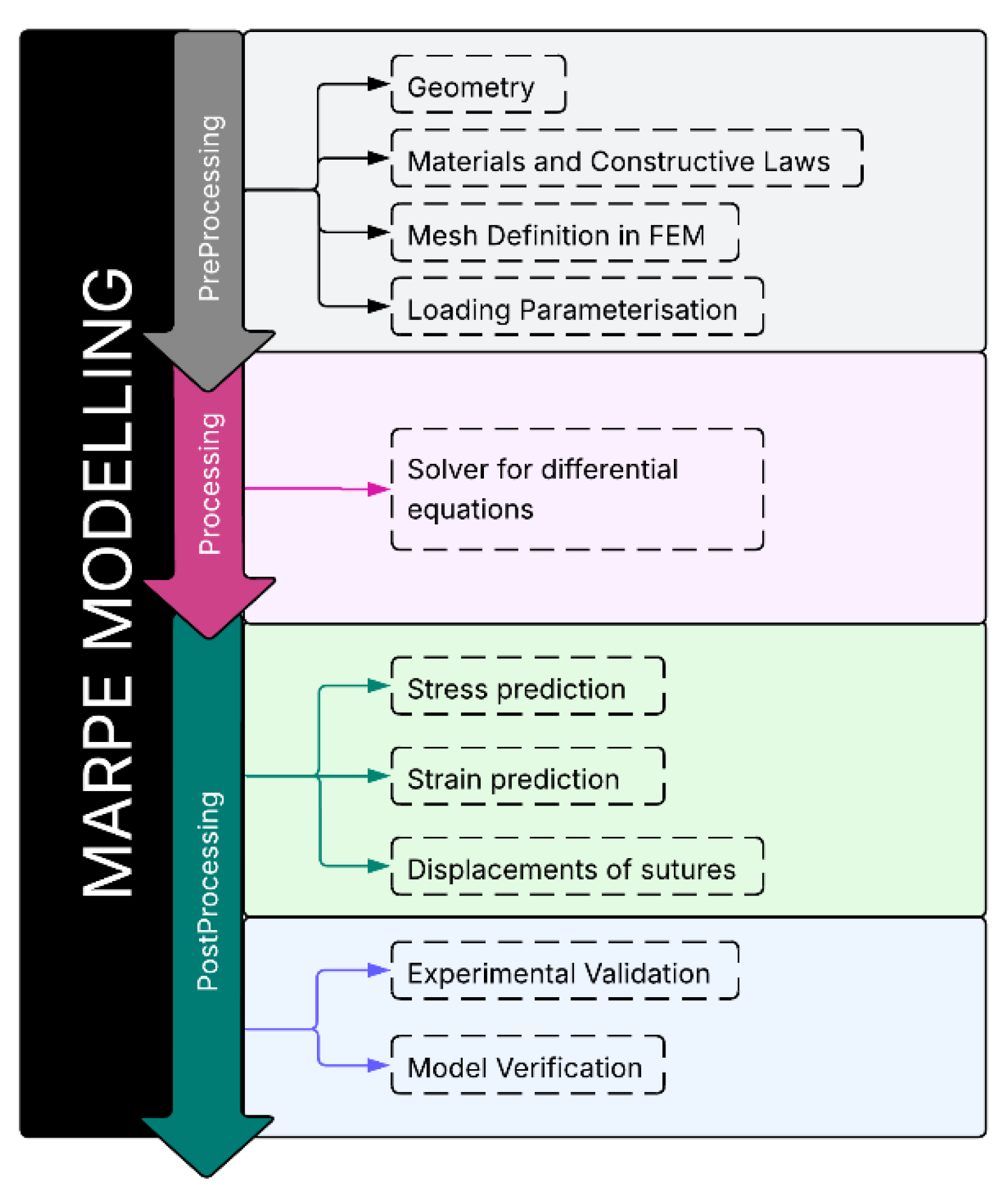

4. FEM-Based Biomechanical Evaluation of MARPE

The FEM workflow included anatomical preprocessing, solver-based processing, and postprocessing for biomechanical outputs, which were subsequently validated against clinical evidence to ensure physiological relevance and interpretative accuracy (

Figure 2).

4.1. Preprocessing Stage

4.1.1. Geometric Definition and Meshing Strategy

3D FEM models have been constructed by detailed 3D X-ray scans of adult human skulls to evaluate the biomechanical effects of MARPE on the craniofacial complex. Scanning parameters typically included slice thicknesses ranging from 0.18-0.3mm and voxel dimensions between 0.3-0.463 mm, providing detailed volumetric data suitable for accurate geometric reconstruction [

34,

37,

42,

45].

Anatomical segmentation of key craniofacial structures was conducted using a combination of semi-automatic and manual techniques. Specialised software, including Mimics, 3D Slicer, or ITK-SNAP, facilitated segmentation through density thresholding and Boolean operations to distinguish and isolate anatomical regions accurately [

38,

42,

47]. The segmentation process prioritised the accurate delineation of critical structures essential for MARPE simulations. The periodontal ligament was modelled as a uniform 0.2 mm layer enveloping the dental roots to replicate physiological conditions [

57]. Craniofacial sutures (e.g. midpalatal or zygomaticomaxillary) were manually delineated with widths ranging from 1.5-2 mm, in alignment with anatomical data from prior studies [

36,

37].

Accurate modelling of the mid-palatal suture - central to transverse expansion biomechanics - is crucial for predicting mechanical responses to MARPE. Stress and displacement patterns showed to be highly sensitive to the number, positioning, and angulation of miniscrews [

39,

40]. In patients with craniofacial anomalies, such as bilateral cleft lip and palate, altered bone morphology further amplifies the need for precise modelling, particularly in regions like the maxillary and pterygoid bones, which experience concentrated mechanical stresses during MARPE activation [

42].

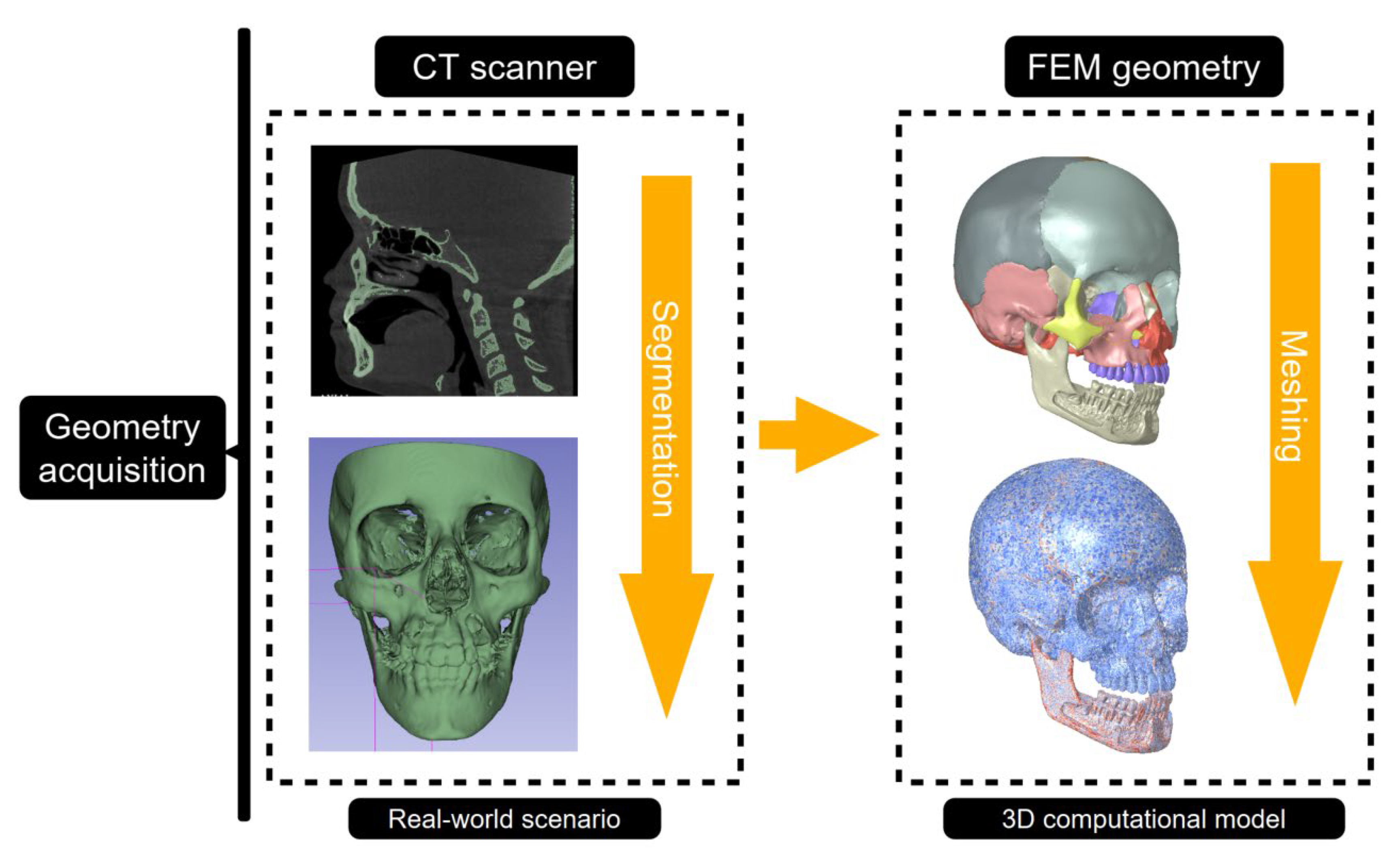

Three-dimensional craniofacial geometries were typically reconstructed from computed tomography datasets (

Figure 3). To enhance anatomical fidelity and prepare models for FEM analysis, extensive image-derived processing steps were applied, including artifact removal, surface smoothing, and mesh optimisation, using software such as Mimics 3-Matic, Geomagic Studio, and Meshmixer. A core-shell modelling strategy was frequently employed to differentiate cortical from trabecular bone, with an offset of approximately 2 mm delineating the inner trabecular volume [

47,

48].

Finalised anatomically accurate models were exported as stereolithography (.STL) files and subsequently converted into volumetric meshes compatible with FEM solvers. Tetrahedral elements were predominantly utilised due to their flexibility in discretising complex anatomical structures, including cortical and cancellous bone, sutures, dental tissues, and miniscrews [

34,

37,

42,

45]. In some cases, specific components, such as the MARPE appliance itself, were discretised with hexahedral elements to improve local stress resolution and enhance numerical accuracy [

47,

48].

In all reviewed studies, FEM simulations were conducted under static loading conditions. Time-dependent or cyclic loading protocols, such as those mimicking chewing cycles, were not implemented. Additionally, masticatory muscle forces—including those from the masseter, temporalis, or pterygoid muscles—were not represented in any boundary conditions or external loading schemes. Instead, forces were applied as fixed magnitudes to miniscrew positions or appliance arms, reflecting simplified expansion mechanics.

Mesh resolution across MARPE finite element studies varied widely, depending on modeling aims (e.g. global displacements, or local stress analysis) and computational limitations. However, a greater number of nodes or elements does not necessarily equate to improved accuracy, particularly if mesh quality criteria - such as element regularity, size transition, and convergence behaviour - are not adequately controlled.

Mesh resolution across MARPE finite element studies varied considerably, with node counts ranging from approximately 45,000 to over 5.5 million and elements from ~40,000 to over 10 million. High-resolution models were constructed by Patiño et al. (2024) (~5.5 million nodes; 1.2 million elements) and Kaya et al. (2023) (2.3–2.5 million nodes; 9.7–10.5 million elements), while coarser meshes were used by Seong et al. (2018) (158,070 nodes; 41,480 elements) and MacGinnis et al. (2014) (91,933 nodes; 344,451 elements) [

13,

38,

41,

42]. Intermediate mesh densities were observed in studies by Gupta et al. (2023) and Rai et al. (2025) (107,858 nodes; 579,088 elements), Oliveira et al. (2021) (251,164 nodes; 137,817 elements), and Mamboleo et al. (2024) (612,101 nodes; 335,834 elements) [

39,

40,

45,

47]. However, the impact of mesh density on model accuracy and performance was rarely quantified, highlighting a critical gap in standardising mesh validation practices in MARPE simulations.

Element sizes were typically region-specific: finer meshes (1–3 mm) were reserved for high-strain zones such as the midpalatal suture and miniscrew-bone interface, while peripheral areas employed coarser elements up to 5 mm to reduce computational costs [

34,

37]. Although mesh quality metrics—such as aspect ratio, Jacobian determinants, and skewness—are essential for numerical reliability, they were seldom reported [

34,

36,

45]. Instead, most studies described general refinement procedures—such as smoothing, artifact removal, and eliminating distorted elements—as a means to ensure convergence and numerical stability [

47,

58].

4.1.2. Materials and Constitutive Laws

In accordance with established modeling conventions in previous MARPE-related finite element studies [

36,

37,

41,

42,

45,

47], anatomical structures and orthodontic appliances were predominantly idealised as homogeneous, isotropic, and linearly elastic materials. While explicit rationales for these assumptions were not consistently articulated across studies, their systematic application implies a methodological necessity to balance anatomical complexity against the computational demands of large-scale biomechanical simulations.

4.1.2.1. Bone Properties

Craniofacial bones, including cortical and trabecular regions, were modelled separately to reflect their distinct biomechanical properties (

Table 2). Cortical bone was typically assigned a Young’s modulus between 13,000 and 14,700 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of ~0.3 [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Trabecular bone exhibited lower stiffness, with reported moduli ranging from 1,370 MPa to 7,900 MPa and similar Poisson’s ratios [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

45,

46,

48]. Some variability was noted, with cortical moduli occasionally reported up to 20,000 MPa and trabecular moduli around 2,000 MPa [

41].

4.1.2.2. Suture Interface Modelling

Craniofacial sutures, critical for accurately predicting stress distribution and deformation patterns in MARPE simulations, were typically modelled as linear elastic, isotropic materials with substantially lower stiffness than bone (

Table 3). Reported Young’s moduli ranged from 10-68 MPa, coupled with near-incompressible Poisson’s ratios (~0.49) to reflect their high deformability [

34,

36,

37,

38,

41].

The midpalatal, zygomaticomaxillary, and pterygomaxillary sutures were consistently modelled across the reviewed studies, typically connecting the maxilla with adjacent bones such as the zygomatic, pterygoid, and frontal bones (

Table 3). In all cases, the suture interfaces were assigned bonded contact conditions. This type of contact definition implies a rigid constraint at the interface, wherein both normal and tangential displacements are fully restricted [

59]. Mechanically, a bonded contact assumes that no separation or sliding can occur between the adjoining surfaces under load, effectively simulating a perfectly adherent interface. While this idealisation simplifies computation and enhances model stability, it does not account for the limited mobility and viscoelastic behaviour observed in craniofacial sutures in vivo. Nonetheless, the uniform application of bonded contact across studies reflects a widely accepted approximation within the current finite element modelling framework for MARPE-related simulations.

While some studies explicitly reported suture mechanical properties, others assumed standard linear isotropic behaviour without numerically specifying material parameters (

Table 2 and

Table 3). This variability in model detailing may limit comparability across simulations and influence the interpretation of biomechanical outcomes. Although modelling approaches varied, particularly in accounting for suture maturation [

13,

48], the consistent representation of sutures as compliant connective tissues aimed to replicate their biomechanical role under expansion loading.

4.1.2.3. Orthodontic Device and Implant Properties

Orthodontic devices, including MARPE appliances and miniscrews, were consistently modelled with properties of biomedical-grade metals. Stainless steel components were assigned an elastic modulus of 190,000-200,000 MPa and ν = 0.29-0.30, while titanium miniscrews (Ti-6Al-4V) were modelled with E values ranging from 110,000-114,000 MPa and ν = 0.30-0.34 [

37,

42,

45].

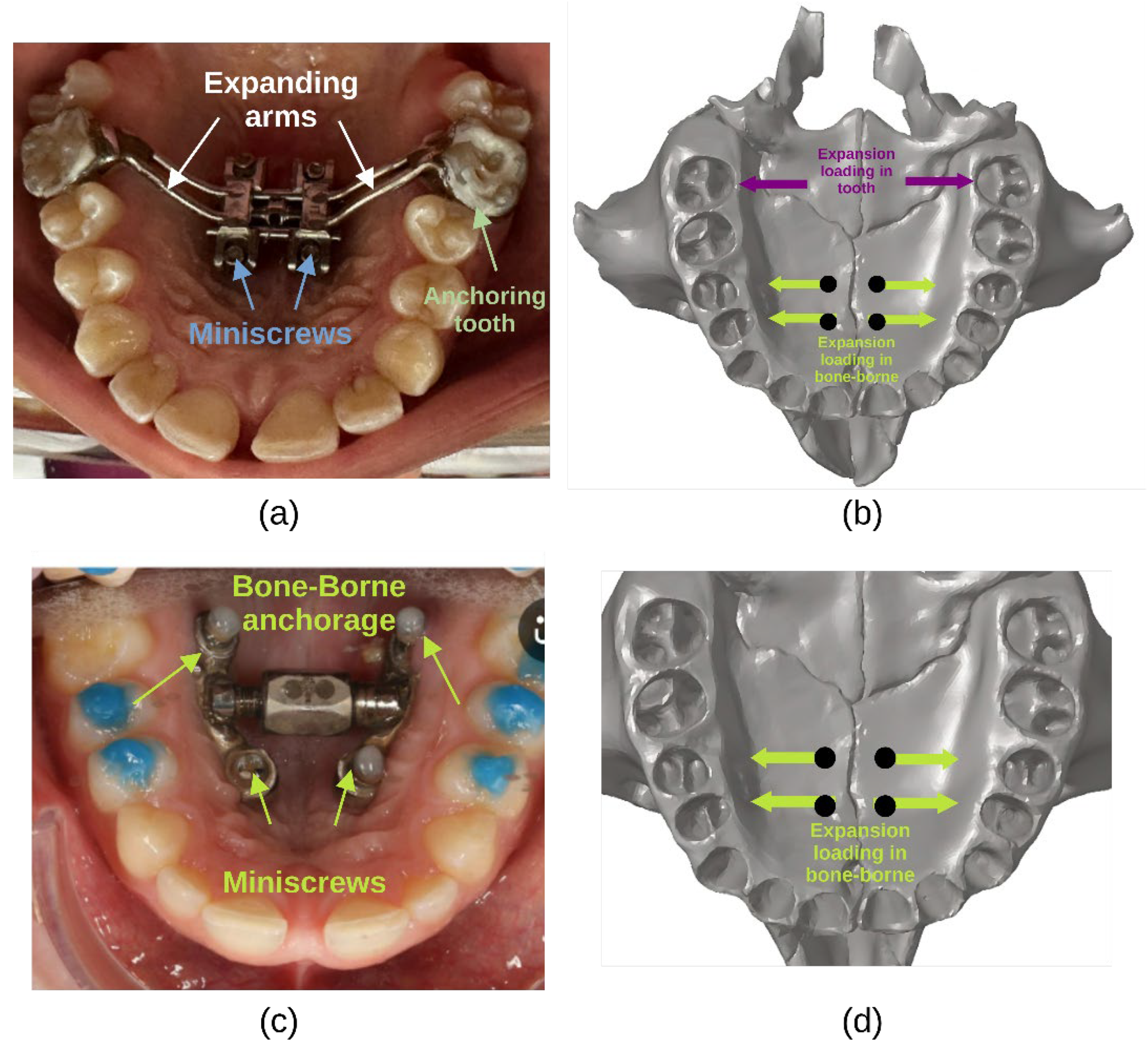

4.1.3. Loading Parameterisation

MARPE-FEM models typically employ either force or displacement-controlled loading to replicate clinical activation protocols (

Figure 4). Expansion forces range from 7.85-9.81 N per side to simulate the transverse forces applied through the expander appliance [

13,

58]. Alternatively, some studies define fixed lateral force magnitudes, such as 100 N applied transversely to the dental anchorage or palatal bone [

38] or 44.5 N per activation turn [

41], to evaluate stress distribution and skeletal displacement.

Another adopted approach involves incremental transverse displacements, simulating activation steps of 0.10-0.25 mm per turn of the expansion screw [

35,

45]. Oliveira et al. (2021) [

45] modelled 0.25 mm per activation step, accounting for both open and closed midpalatal suture conditions, whereas Murugan et al. (2018) used similar incremental activations, continuing expansion until reaching material deformation or failure thresholds. Mamboleo et al. (2024) employed a 0.25 mm displacement per activation turn (0.125 mm per side) to assess biomechanical responses under realistic expansion conditions.

Forces are typically applied at the miniscrew interfaces, anchor teeth (first premolars and first molars), or basal palatal bone [

36,

42,

47] examined the influence of force vector direction, applying protraction forces of approximately 1000 gf per side at angles ranging from −45° to +30° relative to the occlusal plane, demonstrating that load direction significantly influences maxillary displacement and rotation.

4.1.4. Constraints

In FEM models developed for MARPE, constraint assignment is crucial to emulate the anatomical and mechanical boundary conditions of the craniofacial complex. The literature demonstrates a consistent trend of applying fixed boundary conditions at the foramen magnum in all translational and rotational directions [

13,

41,

47]. This approach stabilises the cranial base and minimises rigid body motion during simulation. Some studies extend these constraints to include the forehead or posterior cranial vault [

36,

46,

48], simulating a more extensive stabilisation framework. Alternatively, a few models utilise localised constraints (fixed implants or posterior skull stabilisation) to focus stress distribution around the midpalatal suture or miniscrew interfaces [

39,

42].

4.2. Processing

The processing stage, commonly defined in computational mechanics as the step involving the assembly and solution of system equations, remains insufficiently documented in MARPE-related finite element studies. This lack of detail is not necessarily due to methodological oversight but rather results from the inherent limitations of commercial software environments, such as ANSYS and Altair OptiStruct. In these platforms, solver operations, including matrix assembly, numerical integration, and equation handling, are managed as proprietary processes. Consequently, users have limited control and visibility over these computational steps [

60]. Although methodological standards encourage clear reporting of solver selection, boundary conditions, and convergence strategies to enhance reproducibility, various studies [

42,

45] mainly address the pre-processing and post-processing phases, with little attention to the processing stage.

The limited description of processing steps in MARPE modeling also reflects the relatively recent focus on computational approaches within orthodontic biomechanics. Earlier studies primarily emphasized clinical outcomes rather than modeling details, leading to a gap in documentation. More recent efforts, such as that by Kaya et al. (2023), have started to address this issue by reporting solver specifications and static analysis execution. Nonetheless, the proprietary nature of solver algorithms still constrains the reporting of finer computational details, which challenges reproducibility in MARPE modeling studies.

4.3. Postprocessing

4.3.1. Sutures Displacement and Stress-Strain Prediction

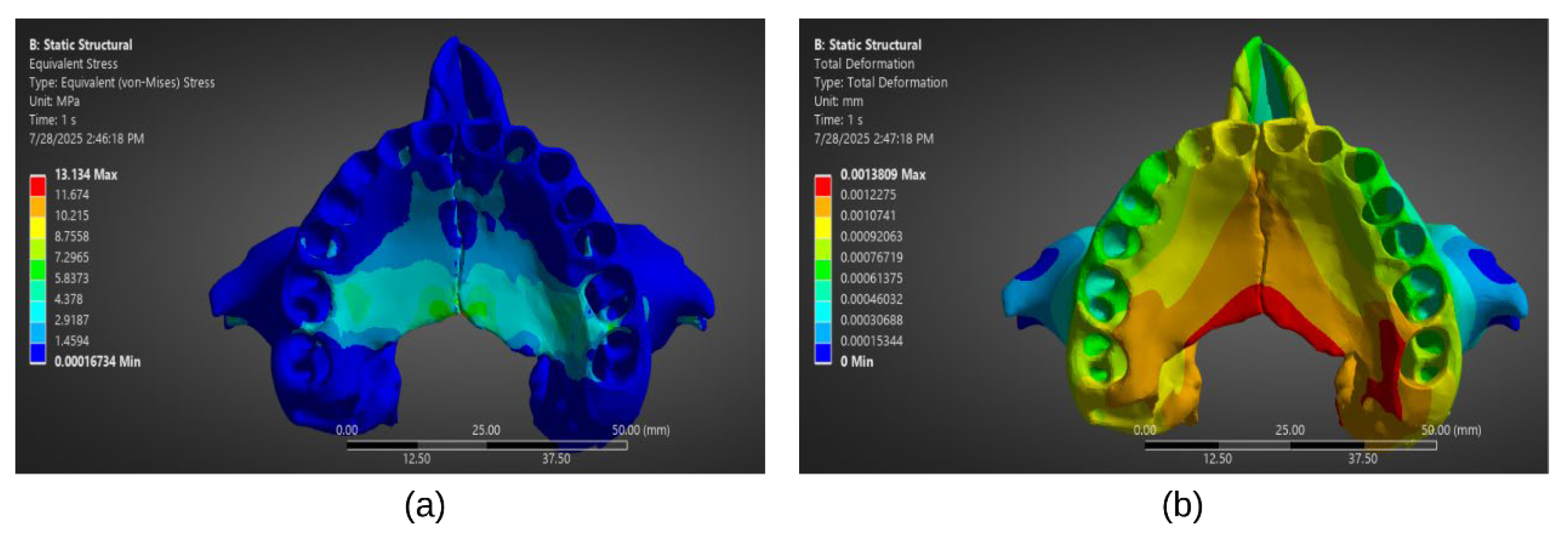

Following convergence of the numerical solution during the processing stage, stress and strain field plots can be extracted for post-processing analysis (

Figure 5). Cortical bone experiences the highest stresses during MARPE activation, particularly in the regions surrounding miniscrews, with values reaching up to 70.27 MPa [

47], mainly concentrated around the miniscrew cavities. In contrast, trabecular bone exhibits lower stress magnitudes, with reported peaks around 5.51 MPa [

47], consistent with its more compliant mechanical nature. The choice of MARPE design and anchorage strategy substantially influences stress distributions. For instance, hybrid appliances incorporating both dental and skeletal anchorage showed broader stress dispersion across the midpalatal suture, resulting in higher strain levels (~4000 µƐ) compared to bone-only or tooth-borne appliances Patiño et al. 2024 and Oliveira et al. (2021) reported that in open suture conditions, stresses in miniscrews ranged from 5,765-10,366 MPa, while appliance arms exhibited stresses up to 9,157 MPa. Conversely, purely bone-anchored expanders confined stress concentrations primarily to the palatal vault, mitigating dentoalveolar impacts [

42,

45].

Sutural displacement patterns reveal a quasi-parallel separation of the midpalatal suture, aligning with MARPE’s orthopaedic objectives. Mamboleo et al. (2024) [

47] quantified an average midpalatal suture displacement of 0.247 mm per 0.25 mm screw activation, corresponding to one activation turn. Similarly, Murugan et al. (2018) observed maximum midpalatal suture displacements of 5.81 mm for Type 1 MARPE and 8.68 mm for Type 2 designs over multiple activations. Displacement magnitudes were notably lower in the anchor teeth compared to the midpalatal region, reinforcing the skeletal nature of MARPE-induced movements. Interestingly, variations in displacement were observed in craniofacial anomalies, with asymmetrical deformation and localised higher strain concentrations on the more severely affected side, particularly in bilateral cleft lip and palate patients [

42].

Beyond stress and displacement, FEM contributes to understanding strain propagation through the craniofacial skeleton. Studies highlight that surgical interventions, such as pterygomaxillary disjunction, significantly alter mechanical responses. Kaya et al. (2023) reported that surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion lowered stress concentrations in the frontomaxillary and zygomaticomaxillary sutures compared to non-surgical MARPE, promoting a more favourable expansion pattern and reducing mechanical overload risks.

Furthermore, the impact of anchorage asymmetry has been underscored. Oliveira et al. (2021) [

45] found that asymmetric miniscrew placements resulted in localised von Mises stresses ranging from 5,765-10,366 MPa on open suture models, significantly higher than symmetric configurations. This underscores the importance of balanced, symmetric anchorage to distribute orthopaedic forces evenly and prevent stress overload. Murugan et al. (2018) corroborated this finding, reporting stress concentrations of 21.1 MPa at the pterygomaxillary junction and 28.1 MPa at the midpalatal suture during maximal MARPE activation.

No additional stress–strain outcomes have been identified in the reviewed MARPE-FEM studies to date.

4.4. Correlation Between Clinical and Computational Data

Validation studies are crucial for verifying the accuracy of computational models in orthodontics, especially in MARPE assessments. These studies ensure FEM models reflect in-vivo biomechanical responses. Despite advances, FEM models often simplify biological structures, highlighting the need for rigorous experimental validation to support clinical decision-making and treatment optimisation [

61,

62].

4.4.1. Experimental Validation

To the best of our knowledge, the databases explored did not report experimental validation studies directly assessing MARPE-induced skeletal changes through FEM; this underscores the continued importance of integrating experimental methodologies to substantiate computational models prior to clinical application. While such validation efforts appear limited in the context of MARPE, studies in other orthodontic domains have sought to validate computational models through experimental techniques, enhancing confidence in their predictive accuracy. Chatzigianni et al. (2011) [

63] evaluated FEM predictions of miniscrew displacement and rotation underloading conditions by comparing them with microCT experimental measurements. Their findings demonstrated a strong concordance between numerical and experimental results, further supported by statistical validation techniques such as the Altman-Bland test and Youden plot. Similarly, Geramy et al. (2018) [

61] validated FEM predictions related to orthodontic loop mechanics by comparing numerical simulations with experimental data obtained using a universal testing machine. Their results confirmed a high degree of agreement for force, moment, and moment-to-force ratio measurements across various activation ranges and angular configurations.

4.4.2. Clinical Validation

Beyond experimental approaches, clinical validation remains essential for assessing the translational accuracy of computational models in real-world orthodontic applications. Knoops et al. (2018) [

62] conducted a validation study on a probabilistic FEM used for predicting soft tissue changes following orthognathic surgery. Their model was compared against pre- and postoperative CBCT scans from eight patients, demonstrating its predictive capability in clinical scenarios. Likewise, Likitmongkolsakul et al. (2018) [

64] compared FEM-based orthodontic tooth movement predictions with actual clinical outcomes in two patients, reporting deviations ranging from 0.003-0.085 mm or 0.36-8.96%. These findings suggest that, while computational models can approximate clinical outcomes with reasonable accuracy, further refinement and validation with larger patient cohorts are needed to enhance their predictive reliability. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies have directly validated MARPE-induced skeletal changes in the clinical setting against FEM predictions.

4. Discussion

The current literature on MARPE biomechanics reveals two critical methodological shortcomings that compromise the comparability of results and their translation into clinical protocols. First, the absence of standardised protocols for miniscrew selection and placement—particularly regarding the use of bicortical versus monocortical anchorage—introduces significant variability in force distribution patterns and expansion outcomes. This inconsistency not only obstructs cross-study comparison but also impairs the development of evidence-based guidelines. Second, the biomechanical strain levels induced by MARPE are rarely quantified with sufficient precision. This gap arises from a combination of factors, including the limited use of high-resolution imaging modalities (low-dose CBCT), reliance on simplified material models, and widespread use of displacement-driven boundary conditions [

37], which may obscure the true force-strain relationships. As a result, the link between applied mechanical stimuli and biological remodelling remains poorly characterised.

To strengthen clinical relevance, future investigations must prioritise the standardisation of implant positioning protocols, explicitly favouring bicortical anchorage to ensure predictable load transfer. Moreover, accurate strain quantification should be achieved through the integration of validated material properties, improved imaging resolution, and force-driven simulation frameworks. Establishing clearer correlations between strain magnitudes and outcomes such as bone remodelling efficacy or post-expansion relapse will enable a more robust biomechanical foundation for MARPE-based interventions.

5.1. Anatomical Fidelity: Segmentation Challenges and Structural Simplifications

A persistent methodological limitation in current MARPE-FEM is the inadequate reporting and validation of mesh quality. While mesh density is routinely mentioned, essential quality metrics—such as element skewness, aspect ratio, and Jacobian determinants [

60,

65]—are frequently omitted. This lack of standardised reporting introduces uncertainty in the accuracy and convergence reliability of simulations, particularly in zones of elevated stress concentration, such as the midpalatal suture and miniscrew interfaces. Without transparent mesh quality assessment, models risk producing artifacts that compromise both mechanical interpretation and clinical applicability. To mitigate this issue, future studies must implement and report standardised mesh validation criteria to ensure numerical stability and reproducibility across research groups.

Equally concerning are the anatomical simplifications that persist in model construction, particularly regarding the uniform assignment of a 0.2 mm thickness to the periodontal ligament (PDL) [

57]. This assumption disregards known patient-specific anatomical variability and fails to capture the PDL’s significant biomechanical influence on local stress gradients [

13,

36]. The physiological accuracy of these models—specifically in terms of stress distribution and soft tissue deformation—is thereby undermined, limiting their value in predicting real-world outcomes. Enhanced anatomical fidelity, particularly through individualised segmentation of PDL and surrounding tissues, would significantly improve the biomechanical relevance of simulations. Finally, the absence of standardised validation frameworks—especially those benchmarking simulation outputs against experimental or clinical data—further limits interstudy comparability and clinical translation. Rigorous validation protocols are essential to elevate MARPE modelling from exploratory analysis to predictive decision-support tools in orthodontics.

5.2. Constitutive Accuracy: Material Properties and Loading Conditions

A critical methodological weakness in existing MARPE-FEM is the inconsistent implementation of loading conditions, particularly the use of displacement-controlled versus force-driven paradigms. Displacement-driven simulations [

40,

45] often yield unrealistically high stress values that exceed the known failure thresholds of craniofacial tissues, despite the absence of clinical failure. These discrepancies likely arise from overly rigid boundary conditions, insufficient mesh refinement, or simplified linear material models. The concern extends beyond MARPE; other dental implant FEM studies [

66,

67,

68] have reported stress magnitudes surpassing material strength by more than fivefold. To improve physiological realism, future simulations should prioritise force-driven protocols, incorporate convergence testing, and calibrate boundary constraints based on anatomical or in vivo data. Such methodological rigour is essential to avoid misleading numerical outputs and to ensure that FEM predictions align with clinical and biomechanical expectations.

In contrast, force-driven simulations [

38,

46] may underrepresent physiological loads, potentially leading to underestimation of tissue strain and limiting predictive utility. This inconsistency diminishes interstudy comparability and restricts the translational relevance of simulation outcomes.

Another methodological simplification observed across all reviewed MARPE-FEM studies is the exclusive reliance on static simulation frameworks and the omission of masticatory muscle forces. No study incorporated cyclic or time-dependent loading to simulate the dynamic nature of chewing, nor did any include muscle-driven vectors such as those from the masseter or temporalis muscles [

13,

36,

58]. Instead, loading conditions were uniformly modelled as constant forces applied to miniscrews or expansion devices. While such simplifications aid convergence and reduce computational cost, they do not reflect the true physiological environment, potentially leading to under- or overestimation of mechanical responses. The absence of muscle-driven boundary conditions is particularly relevant given the role of functional loading in craniofacial adaptation. Incorporating these forces in future simulations may enhance model fidelity and improve alignment with in vivo biomechanics.

Equally problematic is the frequent modelling of the bone–miniscrew interface as a perfectly bonded contact [

37,

41,

48,

58]. This assumption overlooks clinically observed phenomena such as micromotion, partial osseointegration, and implant loosening [

20], all of which are critical determinants of primary stability and long-term success. Ignoring these dynamic biomechanical interactions may lead to misleading conclusions regarding implant stress transfer and anchorage effectiveness. Incorporating nonlinear or frictional contact models—already standard in some dental implant simulations—would provide a more physiologically accurate representation of interface mechanics [

31]. Additionally, the continued reliance on linear-elastic, isotropic material models to describe craniofacial bone fails to capture the anisotropic [

38,

47,

48], heterogeneous properties evident in-vivo. This simplification limits the realism of stress field predictions and weakens their applicability to patient-specific scenarios [

69]. Future studies should integrate anisotropic constitutive models derived from high-resolution imaging and calibrate all applied loads and constraints using experimental or clinical benchmarks to ensure physiological fidelity and clinical relevance.

5.3. Clinical Validation: Methodological Gaps and Translation Challenges

A critical limitation in current MARPE-FEM is their continued reliance on qualitative clinical observations or subjective expert assessments, which substantially undermines their scientific robustness and clinical translatability [

39,

40]. Despite the availability of imaging technologies (e.g. CBCT), quantitative validation methods (e.g. voxel-wise displacement analysis, landmark deviation metrics, or spatial overlap indices), remain largely underutilised [

64]. Moreover, there is a marked absence of longitudinal CBCT validation datasets capable of capturing post-expansion and post-treatment anatomical changes, further restricting efforts to benchmark model predictions against patient-specific outcomes. Limited sample sizes and high inter-patient variability compound these challenges, making it difficult to establish reproducible, generalisable validation protocols across diverse clinical populations.

Beyond these gaps, the biomechanical behaviour of craniofacial structures over time—especially in relation to bone remodelling and orthodontic relapse—is rarely modelled with sufficient fidelity [

29]. Current MARPE-FEM studies typically omit long-term simulations, thereby failing to account for the complex temporal dynamics that shape treatment outcomes. Integrating follow-up imaging data, time-dependent material property evolution, and biological remodelling processes into simulation workflows would significantly improve predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the incorporation of multiscale modelling approaches—particularly agent-based models that capture cellular-scale phenomena such as osteoblast-osteoclast interactions—can complement FEM by linking microscopic biological activity to macroscopic tissue behaviour. These strategies, when embedded in standardised validation frameworks, hold the potential to transform MARPE-FEM from a diagnostic aid into a robust clinical decision-support tool.

5.4. Future Perspectives in Numerical Modelling for Orthodontics

The future of numerical modelling in orthodontics is increasingly shaped by the convergence of artificial intelligence, advanced imaging technologies, and patient-specific biomechanical simulations [

70]. Beyond its established role in automating diagnostics such as cephalometric analysis, AI is now being applied to mesh quality optimisation, material parameter estimation, and inverse FEM for learning constitutive laws directly from clinical data. These developments allow for the construction of more physiologically accurate and computationally efficient models, improving both predictive capacity and clinical relevance. When coupled with high-resolution imaging modalities (CBCT and intraoral scanning) these AI-enhanced workflows support the generation of individualised craniofacial geometries and mechanical profiles, enabling the simulation of diverse treatment scenarios tailored to each patient.

FEM remains fundamental in evaluating orthodontic force systems, incorporating patient-specific parameters such as bone density distributions and heterogeneous soft tissue properties. Advancing clinical applicability necessitates standardised validation protocols and annotated open-access datasets. Integrating FEM with agent-based and probabilistic models holds potential for enhancing predictive accuracy and treatment optimisation.

Finally, future developments in MARPE-FEM should also consider the integration of masticatory muscle forces and dynamic chewing cycles into simulation protocols. Incorporating time-dependent boundary conditions derived from musculoskeletal modelling or in vivo electromyographic data could significantly improve physiological realism. This advancement would allow models to more accurately reflect the mechanical environment experienced during function, enhancing their predictive value for both bone remodelling and appliance performance.

6. Conclusion

MARPE offers a non-surgical solution for maxillary transverse correction in adolescents and adults. This review synthesises clinical and computational evidence on MARPE-induced adaptations, emphasising FEM for biomechanical insights. While FEM elucidates stress distributions, displacement patterns, and sutural responses during expansion, current models are limited by anatomical simplifications, assumptions of bone isotropy/linear elasticity, inadequate suture mechanics, and insufficient clinical validation. To enhance predictive accuracy, future models should integrate detailed anatomy, anisotropic bone properties, age-specific sutural behaviour, and validated loading protocols. Robust validation frameworks using longitudinal CBCT data are critical to align simulations with clinical outcomes. As MARPE evolves, refined computational modelling will optimise device design, reduce complications, and improve treatment precision. Interdisciplinary collaboration and methodological transparency are essential to advance FEM from theoretical exploration to a clinically actionable tool. Prioritising these improvements will support evidence-based, patient-specific MARPE applications in orthodontics.

Author Contributions

Edgar Rivera: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Visualisation, Supervision. Carlos Avila: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. Gabriela Lopez: Investigation, Visualisation, Writing - Original Draft. Paola Tapia: Investigation, Visualisation, Writing - Original Draft. Daniel Ilbay: Investigation, Visualisation, Writing - Original Draft. Paulina Mantilla: Writing - Review & Editing, Formal analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acronym |

Meaning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANSYS |

Engineering simulation software by ANSYS Inc. |

| CBCT |

Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| CIDI |

Context-Instruction-Details-Input (prompting method) |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| FEA |

Finite Element Analysis |

| FEM |

Finite Element Method |

| MARPE |

Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion |

| MTD |

Maxillary Transverse Deficiency |

| OHRQoL |

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life |

| PDL |

Periodontal Ligament |

| RPE |

Rapid Palatal Expansion |

| SARPE |

Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion |

| STL |

Stereolithography (file format) |

References

- Bin Dakhil N, Bin Salamah F. The Diagnosis Methods and Management Modalities of Maxillary Transverse Discrepancy. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Wang K, Jiang C, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, et al. The short- and long-term changes of upper airway and alar in nongrowing patients treated with Mini-Implant Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- McMullen C, Al Turkestani NN, Ruellas ACO, Massaro C, Rego MVNN, Yatabe MS, et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of skeletal and dental effects of treatment with maxillary skeletal expansion. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2022;161:666–78. [CrossRef]

- Chun J-H, de Castro ACR, Oh S, Kim K-H, Choi S-H, Nojima LI, et al. Skeletal and alveolar changes in conventional rapid palatal expansion (RPE) and miniscrew-assisted RPE (MARPE): a prospective randomized clinical trial using low-dose CBCT. BMC Oral Health 2022;22:114. [CrossRef]

- Mehta S, Wang D, Kuo C-L, Mu J, Vich ML, Allareddy V, et al. Long-term effects of mini-screw–assisted rapid palatal expansion on airway: Angle Orthod 2021;91:195–205. [CrossRef]

- Haas, A. Rapid Expansion ofthe Maxillary Dental And Nasal Cavity by Opening The Midpalatal Suture. Angle Orthod 1961;31:73–90.

- Angell, EH. Treatment of Irregularity of the Permanent or Adult Teeth. The Dental Cosmos 1860;1:540–4.

- Sicca N, Benedetti G, Nieri A, Vitale S, Lopponi G, Mura S, et al. Comparison of Side Effects Between Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) and Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (SARPE) in Adult Patients: A Scoping Review. Dent J (Basel) 2025;13:47. [CrossRef]

- Garib DG, Navarro RDL, Francischone CE, Oltramari PVP. Rapid maxillary expansion using palatal implants. Journal of Clinical Orthodontics 2008;42:665–71.

- Tausche E, Hansen L, Hietschold V, Lagravère MO, Harzer W. Three-dimensional evaluation of surgically assisted implant bone-borne rapid maxillary expansion: a pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131. [CrossRef]

- Lee KJ, Park YC, Park JY, Hwang WS. Miniscrew-assisted nonsurgical palatal expansion before orthognathic surgery for a patient with severe mandibular prognathism. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2010;137:830–9. [CrossRef]

- Ventura V, Botelho J, Machado V, Mascarenhas P, Pereira FD, Mendes JJ, et al. Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE): An Umbrella Review. J Clin Med 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- MacGinnis M, Chu H, Youssef G, Wu KW, Machado AW, Moon W. The effects of micro-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) on the nasomaxillary complex—a finite element method (FEM) analysis. Prog Orthod 2014;15:52. [CrossRef]

- Kapetanović A, Theodorou CI, Bergé SJ, Schols JGJH, Xi T. Efficacy of Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) in late adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 2021;43:313–23. [CrossRef]

- Mehta S, Arqub SA, Vishwanath M, Upadhyay M, Yadav S. Biomechanics of conventional and miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion. J World Fed Orthod 2024;13:105–12. [CrossRef]

- Lee RJ, Moon W, Hong C. Effects of monocortical and bicortical mini-implant anchorage on bone-borne palatal expansion using finite element analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2017;151:887–97. [CrossRef]

- Choi EHA, Lee KJ, Choi SH, Jung HD, Ahn HJ, Deguchi T, et al. Skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion based on the length of the miniscrew: a randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod 2023;93:390. [CrossRef]

- Santana LG, Marques LS. Do adjunctive interventions in patients undergoing rapid maxillary expansion increase the treatment effectiveness? A systematic review. Angle Orthod 2020;91:119. [CrossRef]

- Chandran A, Mohode Associate Professor R, Mahindra Professor RK, Suryawanshi Associate Professor G, Mohode R, Mahindra RK, et al. Anatomical variation consideration and guidelines for MARPE placement: A review. International Journal of Applied Dental Sciences 2023;9:40–6. [CrossRef]

- Javier E-N, María José G-O, Pablo E-L, Marta O-V, Martín R. Factors Affecting MARPE Success in Adults: Analysis of Age, Sex, Maxillary Width, and Midpalatal Suture Bone Density. Applied Sciences 2024;14:10590. [CrossRef]

- Zeng W, Yan S, Yi Y, Chen H, Sun T, Zhang Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and stability of miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion in mid to late adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023;23:1–22. [CrossRef]

- Angelieri F, Cevidanes LHS, Franchi L, Gonçalves JR, Benavides E, McNamara JA. Midpalatal suture maturation: Classification method for individual assessment before rapid maxillary expansion. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2013;144:759–69. [CrossRef]

- Redžepagić-Vražalica L, Mešić E, Pervan N, Hadžiabdić V, Delić M, Glušac M. Impact of implant design and bone properties on the primary stability of orthodontic mini-implants. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021;11:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Yoon A, Payne J, Suh H, Phi L, Chan A, Oh H. A retrospective analysis of the complications associated with miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion. AJO-DO Clinical Companion 2022;2:423–30. [CrossRef]

- Kapetanović A, Noverraz RRM, Listl S, Bergé SJ, Xi T, Schols JGJH. What is the Oral Health-related Quality of Life following Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE)? A prospective clinical cohort study. BMC Oral Health 2022;22:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hariharan A, Muwaquet Rodriguez S, Hijazi Alsadi T. The Role of Rapid Maxillary Expansion in the Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Monitoring Respiratory Parameters—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2024;14:116. [CrossRef]

- Hanai U, Muramatsu H, Akamatsu T. Maxillary Bone Fracture Due to a Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Case Report. J Clin Med 2025;14:1928. [CrossRef]

- Holberg C, Rudzki-Janson I. Stresses at the cranial base induced by rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod 2006;76:543–50.

- Winsauer H, Walter A, Katsaros C, Ploder O. Success and complication rate of miniscrew assisted non-surgical palatal expansion in adults - a consecutive study using a novel force-controlled polycyclic activation protocol. Head Face Med 2021;17:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Faria SR de, Andrade TR de, André CB, Montalli VAM, Barbosa JA, Basting RT. MARPE expander activation load with different configurations of extender arms heights: in-vitro evaluation. Dental Press J Orthod 2024;29:e242458. [CrossRef]

- ASME. ASME V&V 40:2018 - Credibility in Medical Device Modeling. 2018.

- Cantarella D, Dominguez-Mompell R, Moschik C, Sfogliano L, Elkenawy I, Pan HC, et al. Zygomaticomaxillary modifications in the horizontal plane induced by micro-implant-supported skeletal expander, analyzed with CBCT images. Prog Orthod 2018;19. [CrossRef]

- Ahn J-W, Choi J-Y, Kim S-H. Is midpalatal suture maturation the major predictor of the success rate of pure bone-borne maxillary skeletal expander?: A CBCT study. Semin Orthod 2025;31:290–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Xu Y, Li C, Zhang L, Yi F, Lu Y. Displacement and stress distribution of the craniomaxillofacial complex under different surgical conditions: a three-dimensional finite element analysis of fracture mechanics. BMC Oral Health 2021;21. [CrossRef]

- Pan S, Gao X, Sun J, Yang Z, Hu B, Song J. Effects of novel microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expanders manufactured by 3-dimensional printing technology: A finite element study. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2023;164:700–11. [CrossRef]

- Moon W, Wu KW, MacGinnis M, Sung J, Chu H, Youssef G, et al. The efficacy of maxillary protraction protocols with the micro-implant-assisted rapid palatal expander (MARPE) and the novel N2 mini-implant—a finite element study. Prog Orthod 2015;16. [CrossRef]

- Murugan R, Shanmugham G, B S, MS K, Murugan N. Stress distribution and displacement of maxilla in micro-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion: A comparative three dimensional finite element analysis. Journal of Clinical Dentistry and Oral Health 2018;2. [CrossRef]

- Kaya N, Seker ED, Yücesoy T. Comparison of the effects of different rapid maxillary expansion techniques on craniofacial structures: a finite element analysis study. Prog Orthod 2023;24. [CrossRef]

- Gupta V, Rai P, Tripathi T, Kanase A. Stress distribution and displacement with four different types of MARPE on craniofacial complex: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Int Orthod 2023;21. [CrossRef]

- Rai P, Gupta V, Tripathi T, Kanase A. Influence of Three Different Vertical Positions of MARPE Expander on Maxillofacial Complex: A Finite Element Analysis. Journal of Indian Orthodontic Society 2025;59:26–35. [CrossRef]

- Seong EH, Choi SH, Kim HJ, Yu HS, Park YC, Lee KJ. Evaluation of the effects of miniscrew incorporation in palatal expanders for young adults using finite element analysis. Korean J Orthod 2018;48:81–9. [CrossRef]

- Patiño AMB, Rodrigues M de P, Pessoa RS, Rubinsky SY, Kim KB, Soares CJ, et al. Biomechanical behavior of three maxillary expanders in cleft lip and palate: a finite element study. Braz Oral Res 2024;38. [CrossRef]

- Hardman P. Structured Prompting for Educators 2023. https://drphilippahardman.substack.com/p/structured-prompting-for-educators (accessed July 13, 2025).

- Avila C, Ilbay D, Rivera D. Human-AI Teaming in Structural Analysis: A Model Context Protocol Approach for Explainable and Accurate Generative AI 2025. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira PLE, Soares KEM, De Andrade RM, De Oliveira GC, Pithon MM, Araújo MTDS, et al. Stress and displacement of mini-implants and appliance in mini-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion: Analysis by finite element method. Dental Press J Orthod 2021;26. [CrossRef]

- Suresh S, Sundareswaran S, Sathyanadhan S. Effect of microimplant assisted rapid palatal expansion on bone-anchored maxillary protraction: A finite element analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2021;160:523–32. [CrossRef]

- Mamboleo E, Ouldyerou A, Alsharif K, Ngan P, Merdji A, Roy S, et al. Biomechanical Analysis of Orthodontic Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion on Dental and Bone Tissues: A Finite-Element Study. J Eng Sci Med Diagn Ther 2024;7. [CrossRef]

- Ouldyerou A, Mamboleo E, Gilchrist L, Alsharif K, Ngan P, Merdji A, et al. In-silico evaluation of orthodontic miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expanders for patients with various stages of skeletal maturation. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh N, Kaur S, Kaur R. MARPE. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2021:86–95. [CrossRef]

- Elshehaby M, Albelasy NF, Elbialy MA, Hafez AM, Abdelnaby YL. Evaluation of pain intensity and airway changes in non-growing patients treated by MARPE with and without micro-osteoperforation: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2024;24:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Moura DB de, Silva EA da, Costa N, Ponte AR da, Santos WRA dos, Souza JRS de. Mini-implant-assisted rapid maxillary expansion (MARPE) for correction of maxillary transverse deficiency in adults: Literature review. Research, Society and Development 2024;13:e91131247735–e91131247735. [CrossRef]

- Marcián P, Borák L, Valášek J, Kaiser J, Florian Z, Wolff J. Finite element analysis of dental implant loading on atrophic and non-atrophic cancellous and cortical mandibular bone - a feasibility study. J Biomech 2014;47:3830–6. [CrossRef]

- Villa-Obando YA, Correa-Osorio SM, Castrillon-Marin RA, Vivares-Builes AM, Ardila CM. Effect of Anchorage Modifications on the Efficacy of Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2024. [CrossRef]

- Walter A, Winsauer H, Crespo E, Walter D, Winsauer C, Schwärzler A, et al. Adult maxillary expansion: CBCT evaluation of skeletal changes and determining an efficiency factor between force-controlled polycyclic slow activation and continuous rapid activation for mini-screw-assisted palatal expansion - MASPE vs. MARPE. Head Face Med 2024;20:70. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Sun W, Li Q, Dong W, Martin D, Guo J. Skeletal effects of monocortical and bicortical mini-implant anchorage on maxillary expansion using cone-beam computed tomography in young adults. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2020;157:651–61. [CrossRef]

- Nienkemper M, Pauls A, Ludwig B, Wilmes B, Drescher D. Multifunctional use of palatal mini-implants. J Clin Orthod 2012;46.

- Mengoni M, Ponthot JP, Boman R. Mesh management methods in finite element simulations of orthodontic tooth movement. Med Eng Phys 2016;38:140–7. [CrossRef]

- André CB, Rino-Neto J, Iared W, Pasqua BPM, Nascimento FD. Stress distribution and displacement of three different types of micro-implant assisted rapid maxillary expansion (MARME): a three-dimensional finite element study. Prog Orthod 2021;22:20. [CrossRef]

- ANSYS. Introduction to Contact. 2020.

- Haider, A. Enhancing Transparency and Reproducibility in Finite Element Analysis through Comprehensive Reporting Parameters A Review. El-Cezeri Fen ve Mühendislik Dergisi 2024. [CrossRef]

- Geramy A, Mahmoudi R, Geranmayeh AR, Borujeni ES, Farhadifard H, Darvishpour H. A comparison of mechanical characteristics of four common orthodontic loops in different ranges of activation and angular bends: The concordance between experiment and finite element analysis. Int Orthod 2018;16:42–59. [CrossRef]

- Knoops PGM, Borghi A, Ruggiero F, Badiali G, Bianchi A, Marchetti C, et al. A novel soft tissue prediction methodology for orthognathic surgery based on probabilistic finite element modelling. PLoS One 2018;13. [CrossRef]

- Chatzigianni A, Keilig L, Duschner H, Götz H, Eliades T, Bourauel C. Comparative analysis of numerical and experimental data of orthodontic mini-implants. Eur J Orthod 2011;33:468–75. [CrossRef]

- Likitmongkolsakul U, Smithmaitrie P, Samruajbenjakun B, Aksornmuang J. Development and Validation of 3D Finite Element Models for Prediction of Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Int J Dent 2018;2018:4927503. [CrossRef]

- Nemade A, Shikalgar A. The Mesh Quality significance in Finite Element Analysis. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE 2020;17:44–8. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos MBF, Meloto G de O, Bacchi A, Correr-Sobrinho L. Stress distribution in cylindrical and conical implants under rotational micromovement with different boundary conditions and bone properties: 3-D FEA. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2017;20:893–900. [CrossRef]

- Tsouknidas A, Lympoudi E, Michalakis K, Giannopoulos D, Michailidis N, Pissiotis A, et al. Influence of Alveolar Bone Loss and Different Alloys on the Biomechanical Behavior of Internal-and External-Connection Implants: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2015;30:e30–42. [CrossRef]

- Tsouknidas A, Giannopoulos D, Savvakis S, Michailidis N, Lympoudi E, Fytanidis D, et al. The Influence of Bone Quality on the Biomechanical Behavior of a Tooth-Implant Fixed Partial Denture: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2016;31:e143–54. [CrossRef]

- Shin H, Hwang CJ, Lee KJ, Choi YJ, Han SS, Yu HS. Predictors of midpalatal suture expansion by miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion in young adults: A preliminary study. Korean J Orthod 2019;49:360–71. [CrossRef]

- Surendran A, Daigavane P, Shrivastav S, Kamble R, Sanchla AD, Bharti L, et al. The Future of Orthodontics: Deep Learning Technologies. Cureus 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).