1. Introduction

Sustainability is a paradigm that can exacerbate the growing pressure humans exert on using natural resources, accelerate climate change, and lead to the loss of global ecosystems. The previous report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) confirmed that anthropogenic activities continue to exert unprecedented pressure on the Earth system, which overlaps in many critical aspects with several ecological objectives of global importance (Zhou et al., 2023). However, contemporary societies should be able to cope with this reality. In that case, they face the challenge of designing and implementing strategies to significantly reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining economic viability and social well-being. The transition to more sustainable production and consumption models requires a deep understanding of the environmental impacts from the extraction to the final disposal of raw materials that uses for generation of products and services that respond to this concern. (Gottinger et al., 2023; Apostolopoulos et al., 2023).

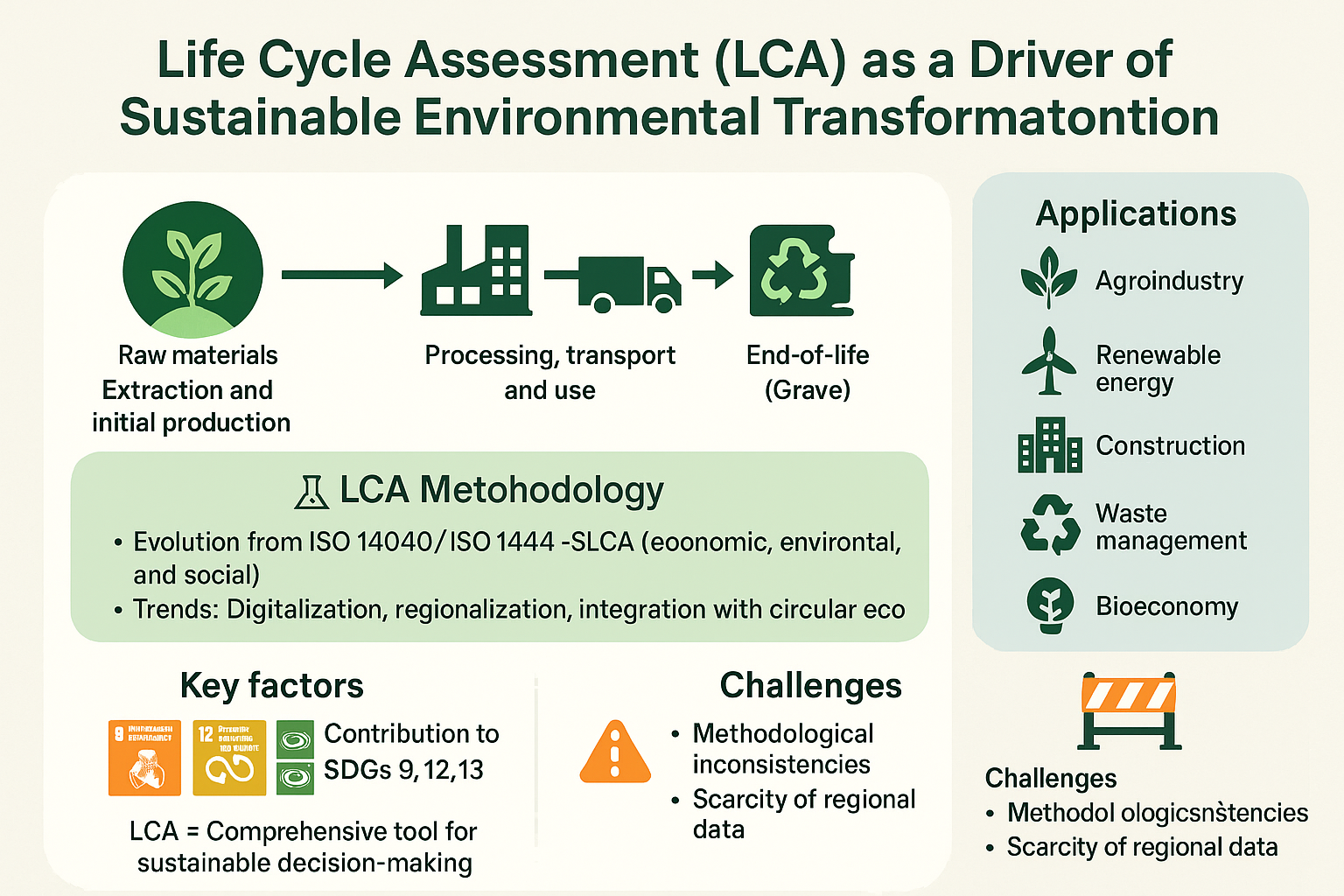

In this sense, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has become an essential methodological tool for systematically quantifying and assessing the environmental impacts of products, processes, and systems. Established as a standard by the International Organization for Standardization and embodied in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, LCA provides a comprehensive environmental analysis system that covers everything from the extraction of raw materials ("cradle") to the final disposal or recycling of products ("grave") (Barbieri & Santos, 2020). The LCA method thus not merely identifies nodal issues from which significant environmental impacts spring, but also markedly increases the contrast between alternative technologies and business processes, thus providing a key tool for decision-makers embarking upon sustainable development (Hicks, 2023).

In recent years, the acceptance of LCA has also been growing, with the scale and spread that we can see today: there has been a lot more scientific publication on this subject, and its principles are increasingly being written into public and commercial policies. It is also in line with the international environmental commitments that the EU is fulfilling (Tagne et al., 2022); for example, it has integrated lifecycle analysis into its European Green Deal and the new Circular Economy and underlines the need for LCA-based environmental reporting for products of all kinds (Röck et al., 2021). Meanwhile, countries like China are gradually integrating the lifecycle approach into their national environmental management regulations, thereby demonstrating their widespread acceptance in the international community (Tang et al., 2024).

LCA has proven particularly useful in the agro-industrial sector for maximizing resource efficiency and identifying new sustainable policies. Recent studies have used LCA to assess the environmental impacts of different cultivation systems, management methods, and food chains (Lago-Olveira et al., 2024). For example, wine research has applied LCA to calculate the environmental benefits of alternative technologies, such as ozonated water used in sustainable control of grapevine diseases, demonstrating significant reductions in the environmental footprint compared to traditional methods. These studies examine greenhouse gas emissions and other ecological indicators such as water scarcity, human toxicity, and eutrophication (Lago-Olveira et al., 2024).

At the energy level, LCA has become a fundamental tool for evaluating and comparing different energy sources and conversion technologies. Multiple studies have applied LCA methodologies to analyze the environmental performance of renewable energy sources such as solar photovoltaic, wind, and bioenergy, as well as emerging technologies such as green hydrogen and energy storage (Hernández-López et al., 2024). These studies have contributed to understanding the environmental benefits and limitations of different energy options, considering direct emissions during generation and issues related to the equipment's manufacturing, installation, and final disposal. For example, recent work on photovoltaic panels has used LCA to evaluate various end-of-life scenarios, including recycling and materials recovery, demonstrating that the cell processing stage accounts for approximately 37% of the total environmental impact (Hernández-López et al., 2024).

In the manufacturing sector, LCA has increased production efficiency and product sustainability, which is consistent with environmental stewardship. Research in the chemical, textile, electronics, and automotive industries uses LCA to determine how materials can be substituted with less toxic or more environmentally friendly materials. Furthermore, recording eco-design or production process improvements will impact a country's production chain. These studies have shown that the most significant opportunities for environmental improvement are not necessarily found in the production phase but rather in stages such as the extraction and processing of raw materials or during the product's service phase—which highlights the need to adopt a holistic lifecycle approach when managing the environment (Paturu & Varadarajan, 2024).

The construction sector, which consumes around 40% of energy and emits 30% of greenhouse gases, has gradually shifted its focus towards greater use of LCA to assess and improve the environmental performance of buildings and infrastructure (Figueiredo et al., 2024). Many studies have used LCA in different types of buildings or construction methods, as well as in various forms of alternative materials and the design of sustainable buildings. Recent research has explored the integration of LCA with digital technologies such as Digital Twin and blockchain to develop dynamic environmental assessments that are capable of aggregating data immediately throughout the building lifecycle, thus innovating compared to the traditional approach based on static historical information (Figueiredo et al., 2024).

LCA has been a key factor in waste treatment, evaluating different treatment and recovery routes, from recycling and composting to incineration with energy recovery or controlled landfill. These studies have identified the best environmental options for different waste streams and multiple impact categories, such as climate change, human toxicity, acidification, and eutrophication (Ceraso & Cesaro, 2024). For example, recent studies on managing plastic waste from express shipments in China have applied Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to compare different management models (landfill, incineration, and mechanical pelletization). So much so that the mechanical pelletization process has significant environmental advantages, generating a potential environmental impact of -215.54 pt, a value much lower than that of landfill (78.45 pt) or incineration (-121.77 pt) (Xu et al., 2024).

Despite significant advances in applying LCA across different sectors, a literature review reveals serious methodological and conceptual discrepancies that complicate comparing studies and consolidating knowledge. These discrepancies are evident in defining functional units and system boundaries, applying impact assessment methods, and interpreting results (Bishop et al., 2021). Take, for example, the field of bioplastics. Recent reviews reveal serious flaws in LCA studies, such as the exclusion of additives from index series, the failure to consider multi-use recyclable plastics and even meaningless accounting of biogenic carbon (Bishop et al., 2021). These methodological disagreements restrict the comparative scope of studies and can lead to contradictory conclusions about the sustainability of specific products or processes.

In this sense, life cycle assessment (LCA) has been increasingly developing, starting from a pure environmental perspective at the initial phase and moving to a more comprehensive approach that includes economic, social, and sometimes even cultural aspects. Thus, a Sustainability Life Cycle Assessment (SLA) was born (Troullaki et al., 2021). This conceptual and methodological approach also responds to the need to assess sustainability from a holistic perspective that simultaneously considers the three component aspects of sustainable development: environment, society, and economy. However, SLA also faces numerous significant challenges in its techniques and methods, particularly in coherently integrating the three dimensions due to insufficient data to assess the social component (Kalbar & Das, 2019).

In this context of the methodological and conceptual evolution of LCA, the central question that inspires this systematic review is: How has Life Cycle Research influenced the environmental transformation of production systems, and what methodological and institutional factors determine its effectiveness as a tool for sustainability? Two specific questions arise from this general issue: (1) To what extent are methodological convergences and divergences in applying LCA in different types of companies, and in each case, how do they affect the comparability and robustness of the set of results? (2) To what extent has incorporating LCA in more complete forms, such as SCL, allowed for successfully addressing the interrelations between sustainability environmental, economic, and social aspects?

Despite the proliferation of reviews in this field of study and the increasing use of LCA methodologies, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding systematic analyses that examine LCA's methodological and conceptual evolution comparatively over time as a tool for environmental transformation. Currently, there are several concerns due to the imbalance in LCA applications, as its deployment is very detailed in specific productive sectors. Instead, practical details related to its development and general use are examined, and the opportunities for LCA's role in guiding sustainable development are not considered (Rodríguez et al., 2020). Overall, institutional and organizational barriers that prevent the widespread adoption of LCA as an environmental management tool persist across diverse geographical contexts and different sectors of society.

Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to critically analyze the status of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as a key element in environmental transformation, its current methodological trends and success factors, and the barriers to its practical implementation in different sectors and geographic regions based on scientific evidence from 2018 to 2024. The specific objectives of this research are to Compare the methodological approaches used in LCA studies of different productive sectors and specify best practices to increase the robustness and comparability of results; examine the evolution of LCA toward more comprehensive approaches such as SCA, analyzing the methodologies proposed to integrate economic and social aspects, evaluating their real contribution to a more holistic understanding of sustainability.

Thus, the systematic review significantly contributes to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, especially SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Furthermore, SDG 13 (Climate Action) addresses the information accumulated on LCA to assess and improve sustainability in processes, products, and services. These results will be particularly valuable for researchers and practitioners wishing to address sustainability-related issues and for managers interested in guiding their decisions toward a more science-based, sustainable economy. This includes identifying effective strategies to reduce the climate pressures exerted by production systems and promoting more circular and climate-stable economic models.

2. Theoretical Foundation

The evolving regime of environmental sustainability, first conceived in the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987), has radically changed; it has evolved from a theoretical principle to a specific methodological tool for practical application. The acceleration of environmental degradation processes, the loss of biological diversity, and the resurgence of widespread extreme weather events have instilled a growing urgency to transition to production and consumption formats that respect the Earth's biophysical limits. The demand for more advanced methods to understand these impacts on our development patterns and pathways (including industrialization and urbanization) has led Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to its current strong position for such purposes (Hauschild et al., 2018).

The application of Life Cycle Assessment is therefore considered an integrative approach to addressing the environmental sustainability of products, processes, and services throughout their value chain. This approach provides a holistic view that clarifies critical points requiring improvement or intervention (ISO, 2006a). This field of study has experienced exponential growth in the last decade, with an annual increase in scientific publications of 30% since 2010 (Moutik et al., 2023). This growth consolidated the discipline in the academic sphere and brought greater importance to public policy and business management. This is where the systematic quantification of environmental impacts is essential for making well-informed decisions.

According to ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, the LCA cycle consists of four interconnected stages, thus determining its methodological structure: objective definition and scoping, inventory analysis (ICC), impact assessment (LCIA), and interpretation of results (ISO, 2006b). The first stage delimits all relevant aspects of a study, including the functional unit and system boundaries. The inventory analysis completes and quantifies the material and energy flows associated with the activity under analysis. The impact assessment characterizes these flows according to different environmental impact categories. Finally, interpretation recapitulates the results and suggests ways to improve environmental performance. This completes a cycle that can provide feedback on how the analysis is conducted and the results themselves.

The evolution of concepts and approaches in this field reflects how these theories have adapted to changing ecological priorities worldwide. LCA, which initially focused more on energy analysis and material balances, has since incorporated new impact categories, more complex assessments (making them feasible from eco-social perspectives), and economic considerations into its toolkit, complementing the traditional environmental perspective (Guinée et al., 2011). Initiatives that were not endorsed by GLAM (Global Guidance for Lifecycle Impact Assessment) seek to harmonize methodologies and characterization factors across all scales worldwide and include innovations such as the potential extinction of species and the effects of microplastics in their analyses (Schumacher & Willems, 2024).

When applied to different areas, such as the food industry, which has served to compare conventional systems with alternative systems, this has simultaneously allowed for the identification of ways to balance different impact categories, leading to the optimization of resource efficiency once these have been identified (McAuliffe et al., 2018). Many manufacturing companies have promoted the application of LCA, leading to the development of eco-innovation and eco-design in the initial stages of product development, minimizing their environmental impacts from conception (Zheng et al., 2018). When comparing the environmental impacts of different energy sources, LCA has been used frequently in this sector to validate the differences between conventional and renewable sources, incorporating indirect impacts that are omitted in simplified energy assessments. Construction is a field in which environmental impact is significant, given the average life of a building and its applicable period over time. As a result, LCA has recorded a notable increase in the search for materials with a lower green footprint (Dong & Ng, 2015).

There is a consistent pattern in the scientific literature on LCA: the life cycle assessment is now adopted at all stages to avoid shifting environmental burdens between them; standardized impact categories are recognized; the methodology established by international standards marks a starting point (Brandão et al., 2024). At the same time, there are disagreements regarding assessment methods, the selection of functional units, and their integration into the socioeconomic dimensions of the system. These disagreements underscore any sustainable development framework's intrinsic complexity and highlight the normative nature of many methodological choices. Thus, it is necessary to interpret the results clearly and in their context.

The alignment of LCA and the SDGs represents a strategic opportunity that can serve as a real channel for achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda, both in products and services. These conceptual frameworks show that no procedure allows us to establish and analyze associations or provide feedback between the two trends (E Sanyé-Mengual & Sala, 2022). LCA makes a significant contribution to SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production) through quantitative impact data that allows the identification of inappropriate procedures and the development of more efficient alternatives within supply chains. LCA can calculate greenhouse gas emissions and provide information that helps adopt more effective measures to address international environmental commitments (SDG 13, climate action). Specifically, regarding SDG 9 (Industry Innovation and Infrastructure), LCA contributes to innovation by being oriented towards sustainable development and constructing infrastructures that improve and are less harmful to the environment (Cremiato et al., 2018).

In academic departments of environmental management or sustainable development where there is an urgent need to understand the effects of the most important factors for decarbonization and energy transition, LCA provides crucial information for preventing environmental damage caused by business activities. Computerized systems can be of great help. Furthermore, biodiversity is slowly becoming one of the most critical elements for planetary sustainability. Following the Kunming-Montreal framework, indicators are been developed in 2021 to measure trends in depreciated biodiversity gains and losses (Marques et al., 2019). One of these, called "Net Biodiversity Gain," allows for systematic observation and monitoring of biodiversity.

Due to the robust life cycle assessment methodology, some limitations must be considered when applying it. The data intensity required for comprehensive analyses may prevent its use in data-poor settings. The uncertainties associated with modeling complex and dynamic systems introduce variability into the results, requiring open and honest communication. The most appropriate way to include temporal and spatial aspects in impact assessments remains a difficult methodological challenge (Hauschild et al., 2018). These limitations have encouraged additional developments such as Social Cycle Assessment (SCA) and Sustainability Cycle Assessment (SCA), which integrate the three dimensions of sustainable development with a comprehensive assessment (Iofrida et al., 2018).

New trends show a sustained effort to overcome these problems and expand the use of LCA. Combined with artificial intelligence, big data, and digital twins, they make it possible to collect, process, and implement information, eliminating time constraints for application in different scenarios. The Social Footprint methodology can quantify large-scale social impact through national statistics; However, specific data on technologies or companies is unavailable; this methodology covers more than 99% of the world regarding GDP, population, and carbon footprint (Weidema, 2018). Furthermore, introducing LCA into conceptual frameworks such as the circular economy has changed the analysis and its limitations, leading to assessments that extend beyond a single product to interconnected production systems (Niero & Kalbar, 2019).

In summary, LCA is considered a basic and high-quality tool for advancing environmental sustainability, providing appropriately analyzed quantitative evidence in different contexts that provides a basis for decision-making. Replacing a crude and fragmented assessment with a systemic approach increasingly reflects an understanding of contemporary sustainability challenges. This methodological reinforcement based on international standards combined with original proposals aims to expand the scope of application and the significance of its results. In the context of multiple and intertwined crises in the environmental field, LCA is emerging as an important link between sustainability theory and its practical implementation. It can serve as a guide for promoting transitional paths that integrate economic and social well-being goals with effectively conserving ecosystems that sustain life on Earth.

3. Materials and Methods

The literature review follows the PRISMA 2020 method, which includes the systematic identification of relevant literature, preliminary selection of studies, eligibility assessment based on specific criteria, and the final inclusion of papers for analysis. This systematic approach ensures the transparency and reproducibility of the research process, two essential aspects if the underlying literature review is to have high academic value (Page et al., 2021).

The strategic choice of Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect as databases are based on "their prestige and notoriety," "their high impact," and their "interdisciplinary nature." This strategic choice allows us to focus directly on research, as they are home to disciplines as diverse as environmental science, engineering, economics, and social sciences (Moutik et al., 2023). Furthermore, these platforms, along with the other existing registries in our country, are ideal for a comprehensive review of sources related to Life Cycle Assessment and sustainability.

The 2018-2024 period was chosen considering the dynamics of change within each discipline. Thus, significant changes were made in international environmental policies, advanced LCA methodology, and its application in different sectors during that period. It is also important to note that this period coincides with a widespread proposal toward consolidating the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, which is an important catalyst in both the theory and practice of this activity. In recent years, according to Sanyé-Mengual and Sala (2022), an upward trend has been observed, this trend combine the circular economy, sustainability indicators, and the lifecycle approach.

To ensure a systematic search of relevant literature, a search strategy was created that combined keywords with Boolean operators, forming the following basic equation: ("life cycle assessment" OR "LCA" OR "análisis de ciclo de vida") AND ("sustainability" OR "sostenibilidad") AND ("environmental impact" OR "impacto ambiental") AND (2018–2024). We used this formula in each article's title, abstract, and keyword fields to maintain the thematic relevance of the results. Given the need to capture basic terminology and the idiomatic variations in which it appears, which reflect the breadth of the literature currently available, the structure responds to these terms included in the review of the databases, aligned with the object of study.

When defining parameters to determine which studies would include in the research and which would exclude, the quality and relevance of those studies considered to guaranteed through the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusivity aspects established rigorously, prioritizing: 1. Articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, thus guaranteeing the quality of the methodological research at its source; 2. Studies published in English or Spanish because these are the predominant languages in the global scientific literature on this topic; 3. Works published from 2018 onward guarantee the currency of the findings; 4. Studies that explicitly establish conceptual or methodological connections between lifecycle analysis and sustainability; and 5. Works that present empirical applications and clear methodological developments with relevant and beneficial conceptual frameworks for integrating lifecycle analysis into sustainability strategies.

In compliance with the exclusion criteria, the following considered: (1) conference proceedings, editorials, congresses, letters to the editor, or other material not subject to peer review; (2) articles without access to their full content, so they could not be thoroughly evaluated; (3) research that only deals with technical aspects of LCA, without directly relating sustainability as an integrative conceptual framework; (4) studies whose main objective was not the link between LCA and sustainability; and (5) literature reviews that were not systematic or narrative, giving priority to works with a more rigorous and methodologically sound approach. As Hauschild et al. (2018) explain, this precise delimitation is essential to ensure the thematic coherence and methodological soundness of the primary data set analyzed.

The methodological process continued with the serial selection of studies through various filtering phases. First, after searching the selected databases, the results were exported directly to a bibliographic manager, enabling better document management without worrying about duplicates. Next, the title and abstract are reviewed to screen the documents, followed by what is known as a close reading of the text. Consequently, this process allowed for incremental and well-founded discrimination, ultimately constituting the definitive corpus of studies that would serve as the analytical basis for the present research.

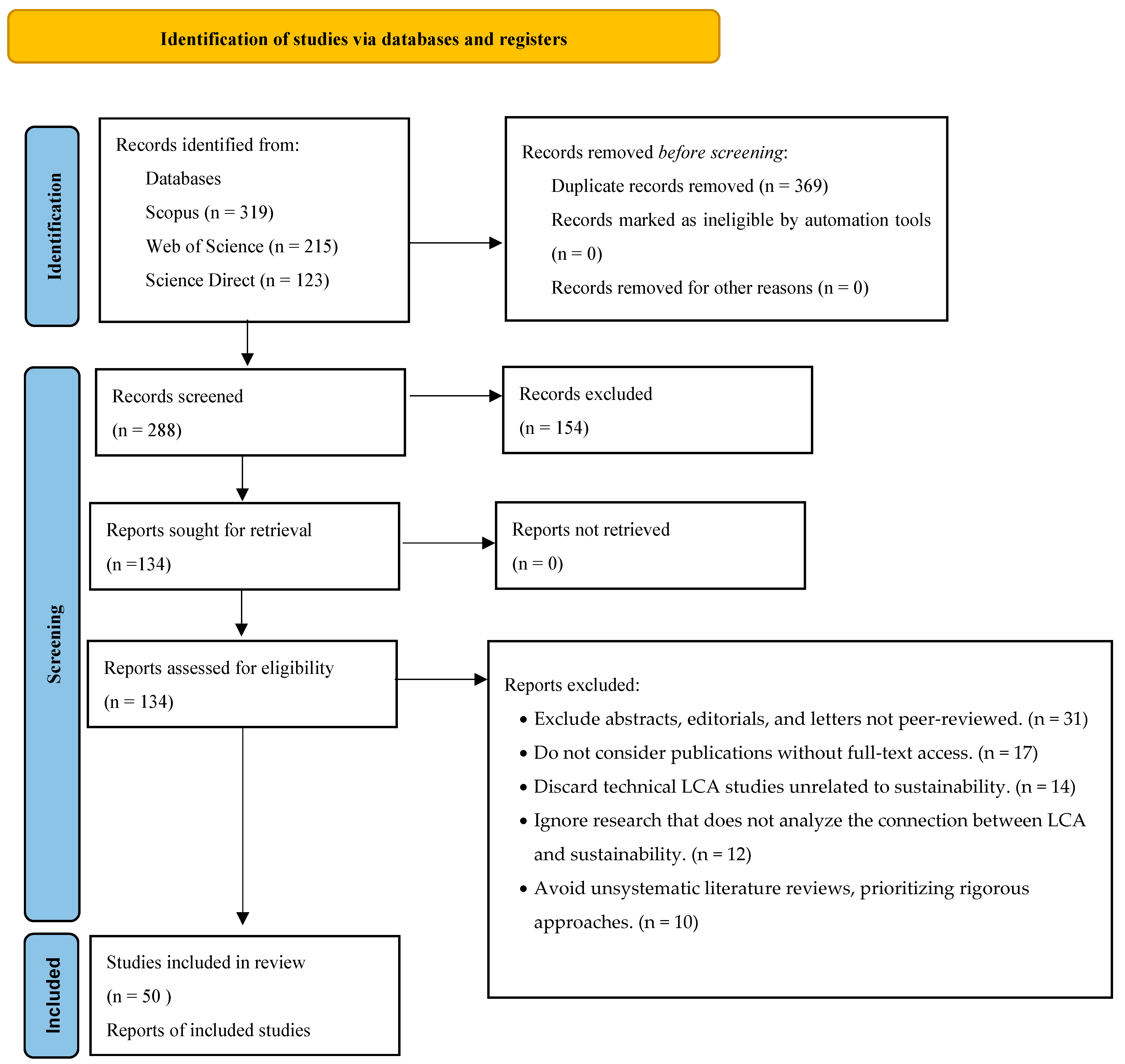

This systematic review conducted a rigorous literature selection process, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) model's guidelines to ensure transparency, traceability, and methodological consistency. The process followed the four stages: identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion.

In the identification phase, the first process, 657 information sources were selected from three high-impact scientific databases: Scopus (n = 319), Web of Science (n = 215), and Science Direct (n = 123). These platforms were selected for offering comprehensive thematic coverage, accurately reflecting the content of peer-reviewed publications, and being internationally recognized as primary sources for analyzing relevant scientific literature. Other records from manual literature and institutional records were not considered.

Immediately afterward, before beginning the screening, 369 duplicate documents were excluded using similarity detection software (Mendeley). Other records could also have been eliminated for various reasons (inappropriate topics or indexing errors). Although this number is not detailed in the database, it is indicated as "n = 0" in the PRISMA diagram.

In the screening phase of the titles and abstracts of the remaining 288 records, we sought to discard those that did not align with the previously defined objectives and inclusion criteria. As a result of this preliminary review, 154 studies that did not meet the minimum requirements regarding topic, document type, and scientific quality were excluded.

In the eligibility assessment phase, we attempted to obtain the full texts of those studies that passed the screening process (n=134). From the full texts retrieved, the 134 articles were subjected to a comprehensive analysis for their methodological and conceptual relevance. At this stage, 84 studies were excluded for various reasons: 31 were abstracts, editorials, and letters to the editor that had not been peer-reviewed; 17 lacked access to the full text; and 14 were technical studies on lifecycle assessment that had no direct relationship to sustainability. Of the remaining 12, the relationship between LCA and sustainability was not explicitly addressed. Furthermore, 10 were non-systematic literature reviews whose methodology did not meet the standards required for such research.

As a result of this systematic and judicious process, the final inclusion phase included 50 studies that fully met the criteria for quality, thematic relevance, accessibility, and methodological validity (See

Figure 1). These studies form the documentary and theoretical basis for this systematic review and allow us to jointly address the phenomenon under study with reliable and up-to-date scientific support.

VOSviewer was used to conduct a parallel bibliometric approach to qualitative analysis. This tool allowed for graphical visualization of the network of interrelationships between key concepts and networks of terminological co-occurrence, thereby identifying thematic clusters, emerging trends, and conceptual patterns. The bibliometric approach is not the focus of this study, but its purpose is to complement the documentation developed qualitatively.

The internationally validated Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) instrument was used to ensure the methodological quality of the included studies.

Table 1 summarizes the quality assessment of some of the most significant studies reviewed.

The resulting demonstrative process provided an objective view of the methodological robustness of the analyzed research, significantly increasing the solidity of the previous conclusions. Furthermore, it is worth noting that using CASP requires a series of fundamental requirements: clarity of objectives, adequacy of the method, validity of the results, and applicability of its conclusions. Thus, another scientific quality filter was also established. As Iofrida et al. (2018) point out, this assessment approach is essential for distinguishing between different research paradigms and the corresponding epistemological consequences in Social LCA.

In short, the methodological approach developed comprises a combination of systematic review, quantitative analysis, bibliometric exploration, and critical appraisal. Thanks to this multi-methodological approach, not only were important articles identified from recent literature, but convergences and divergences between different conceptual frameworks were also established. Although the results may be ambiguous, they allow for presenting the type of arguments typically presented in some instances. Therefore, this approach seems highly appropriate for interdisciplinary and dynamic fields, as it combines perspectives that complete the interpretation of the results (Guinée et al., 2011).

Another relevant aspect that should be acknowledged in the present study is methodological limitations. First, the language restriction to publication in English and Spanish may exclude some interesting works in other languages. Similarly, the fact that the temporal coverage starts afterward since a fix point may mean that earlier developments are lost, which would undoubtedly benefit the analysis from a historical perspective. Content-relevant reports, such as doctoral theses, other scientific documents, and foreign publications, may also be excluded when repositories are not included. However, these restrictions were not imposed arbitrarily but were considered as feasibility, rigor, and methodological consistency criteria.

During the selection process, special attention was given to studies demonstrating the link between life cycle assessment and sustainability conceptual frameworks, especially those that propose explicit connections with the Sustainable Development Goals. This selective focus reflects the primary objective of the research: to examine the transformative potential of LCA as a tool for meeting global environmental goals (Niero & Kalbar, 2019).

Finally, this methodology provides a robust procedural model that ensures the comprehensiveness and quality of document analysis. The combination of qualitative, quantitative, and evaluative approaches guarantees a methodological foundation consistent with the standards of high-impact scientific publications. This solid construction allows for a rigorous analysis of Life Cycle Assessment conceptual and applied development (LCA) as a transformative environmental tool.

4. Results

Dimensions of Life Cycle Assessment in Sustainability

Table 2.

summarizes the dimensions that allow the analysis of evolution, methodological trends, barriers, and sectors where the life cycle can be implemented.

Table 2.

summarizes the dimensions that allow the analysis of evolution, methodological trends, barriers, and sectors where the life cycle can be implemented.

| Dimension |

Evolution 2018-2024 |

Methodological Trends |

Barriers |

Featured Sectors |

| LCA Methodology |

The transition from purely environmental approaches with ReCiPe and CML methods (2018-2019) to dynamic frameworks with digital integration (2022-2024), including the consolidation of methods for regionalization and uncertainty (2020-2021). |

Integration of specific temporal and geographic scales. Advanced mapping and validation methods. Adaptation of ISO standards to specific contexts. Consistent approaches for systemic change. |

Inconsistencies in system boundaries. Limited availability of primary data. Increasing model complexity. Insufficient standardization. Limited comparability across studies. |

Renewable energy. Sustainable mobility. Sustainable construction. Waste management. Bioeconomy and biomaterials. |

| Sustainable LCA |

Evolution from initial integration proposals (2018-2019) towards consolidated frameworks such as FELICITA with fuzzy logic and participatory approaches (2022-2024). |

Simultaneous integration of environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Quantifiable social indicators. Participatory approaches. Transparent multi-criteria methods. The balance between complexity and applicability. |

Subjectivity in the weighting of dimensions. Limited social and economic data. Incommensurability of impacts. Communication complexity. And a lack of methodological consensus. |

Bioeconomy and agri-food. Integrated mobility. Circular models. Sustainable urbanism. Public policies. |

| Temporal Dimension |

Progression from static approaches (2018-2019) towards dynamic methods with predictive capacity and integration with complex models and real-time evaluation (2022-2024). |

Dynamic modeling with variable temporal resolution. Integration with prospective analysis. Evaluating emerging technologies. Considering systemic feedback. Robust uncertainty quantification. |

Projections, computational complexity, the limited availability of temporal data, long-term validation, and the representativeness of future scenarios all involve uncertainty. |

Energy transition. Adaptive resource management. Long-term infrastructure. Disruptive innovation. Climate adaptation. |

| Sectoral Applications |

Diversification from traditional sectors (2018-2019) towards complex and interconnected systems with highly adapted methodologies (2022-2024). |

Sector-specific functional units. Consideration of entire value chains. Integrated complementary methodologies. Relevant impact categories. Sector-specific allocation. |

Limited intersectoral comparability, reduced methodological transferability, disparity in sectoral data, complexity in global supply chains, and technological specificities are also issues. |

Biorefineries. Battery technologies. Agribusiness. Biocomposites. Electronic waste. Smart urban systems. |

| Circular Economy |

Evolution from initial adaptations for recycling (2018-2019) towards integrated LCA-Circularity frameworks with holistic evaluation of circular strategies (2022-2024). |

Boundary expansion for multiple cycles, specific circularity methods, evaluation of product-service systems, integration with a circular design, and consideration of material and energy cascades. |

Complexity in circular modeling. Multicyclic allocation. Indirect effects and rebound. Modeling complex systems. Long-term uncertainty. |

Recovery of critical materials. Product service systems. Industrial symbiosis. Remanufacturing. Collaborative consumption. |

| Regionalization |

Transition from generic factors (2018-2019) to advanced methods of complete regionalization adapted to different administrative levels (2022-2024). |

Regional characterization factors. Consideration of local energy mixes. Adaptation to specific regulatory frameworks. Inclusion of socioeconomic conditions. Multi-scale spatial assessment. |

Limited regional data. Low interregional transferability. Questionable local representativeness. Multiregional complexity. Variability of local conditions. |

Territorial planning. Global chains. Local water management. Territorial food systems. Sustainable urban management. |

| Digitalization |

Progression from traditional software (2018-2019) to advanced integration with blockchain, IoT, digital twins, and machine learning (2022-2024). |

Data collection and processing automation. Real-time monitoring. Blockchain traceability. Artificial intelligence modeling. Interoperability between systems. |

High implementation costs. Specialized technical requirements. Limited interoperability. Data privacy and security. And management and validation complexity. |

Industry 4.0. Precision agriculture. Smart buildings. Advanced supply chains. Real-time environmental monitoring. |

| Policies and Communication |

Evolution from limited academic applications (2018-2019) to a key tool for policy design and integration into corporate reports (2022-2024). |

Adaptation to policy frameworks. Integration into policy analysis. Life-cycle-based instruments. Evaluation of regulatory measures. Support for sustainable development goals. Democratization and accessible visualization. |

Technical-political gap. Oversimplification. Institutional resistance. Regulatory integration. Jurisdictional harmonization. Communications complexity. |

Sustainable product policies. Decarbonization strategies. Green public procurement. Labeling. Environmental economic instruments. Corporate communication. |

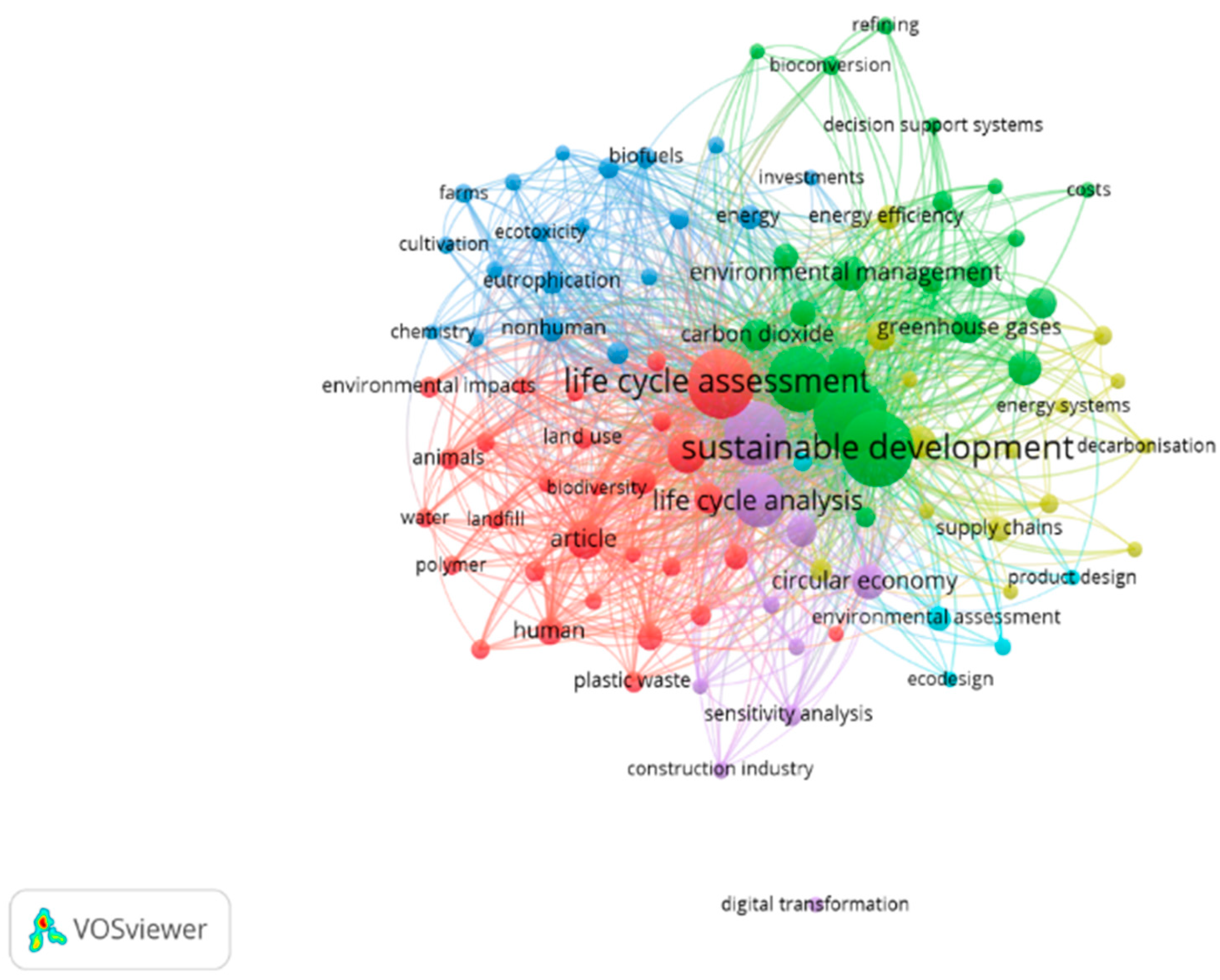

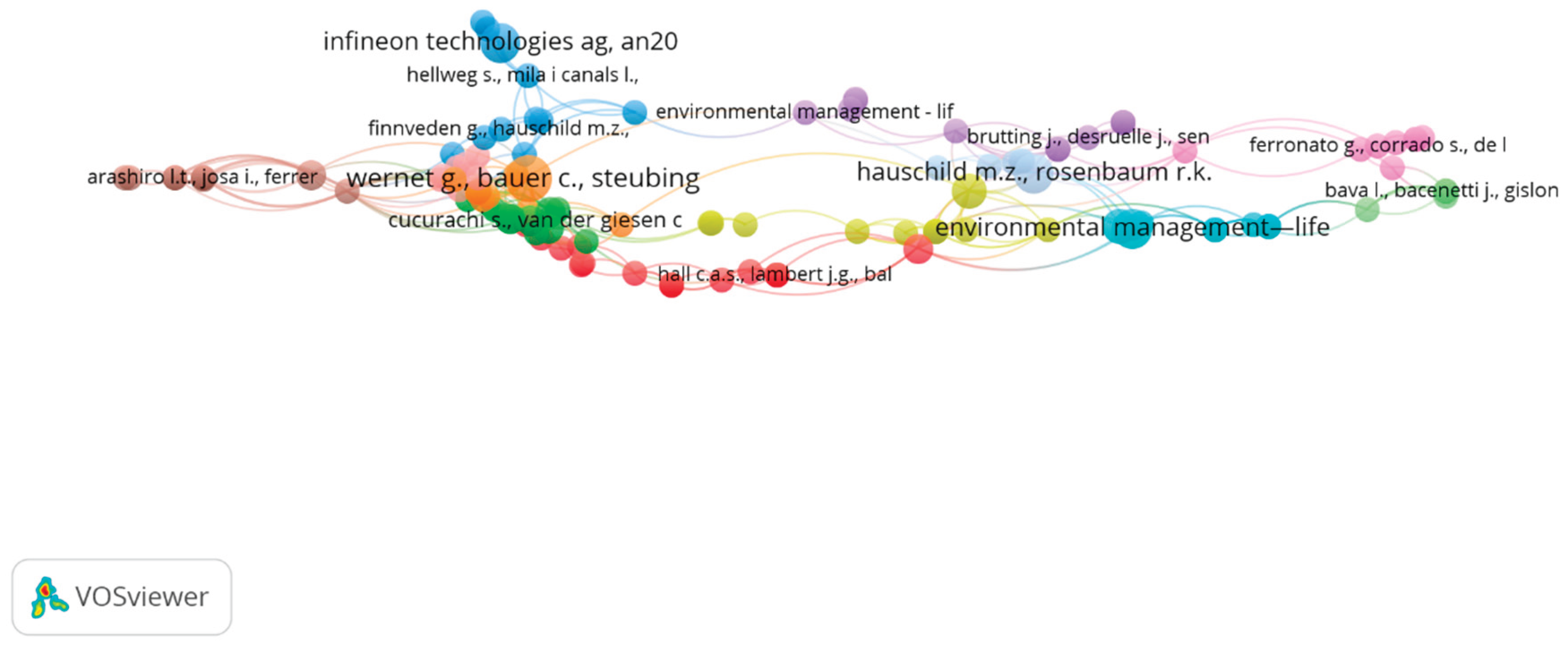

Next, reviewing the bibliometric analysis with VOSviewer demonstrates the conceptual relationships or key themes among all the data. The co-occurrence map (

Figure 2) projects all directions and interrelationships, showing the nodes and complexity of LCA's role in the current academic discourse on environmental transformation.

The research proposes a renewed perspective on sustainability, placing life cycle assessment (LCA) as a central tool for driving systemic environmental change. The bibliometric analysis visualized in the image using VOSviewer supports this premise by highlighting, through the co-occurrence networks of terms, the relevance and centrality of LCA in current academic discourse.

The LCA methodology emerges as the central node. The term "life cycle assessment" is interconnected throughout the network and is closely associated with "sustainability." This turning point has ultimately become key to everything done to guide and achieve sustainability strategies, positioning itself as a bridge between management and sustainable development policies. In other words, LCA does not act independently instead operates in various areas—environmental, economic, and social—and its methods integrate judgment criteria throughout the entire value chain.

The network is organized into five main clusters, each representing a complementary thematic focus. The green cluster, which immediately features terms such as "environmental management," "greenhouse gases," and "energy efficiency," reflects the concerns of those advocating for positive environmental change. The inclusion of this group indicates that LCA research and practice are closely intertwined with emissions measurement and the optimization of energy processes, aligned with current global priorities for reducing greenhouse gases and transitioning to sustainable energy systems.

On the other hand, the red cluster, which contains keywords such as "human," "biodiversity," "land use," "plastic waste," "environmental impacts," and so on, reveals a greener and more social aspect, linking it to the life cycle of ecosystems and population. This group expands the scope of LCA beyond purely environmental metrics, considering other terms such as environmental justice and human health. Likewise, the cluster terminology, for example, "animals" or "nonhuman," also indicates a growing interest in interspecies aspects, representing a new trend for total sustainability theory.

The blue cluster focused on "biofuels," "ecotoxicity," "cultivation," and "eutrophication," shows where agricultural and industrial sustainability intersect. Indeed, for bioenergy, LCA assesses the critical balance between benefits and secondary harms based on energy needs, pollution, and soil and water degradation. This cluster reveals fundamental tensions in the trade-off between fossil fuels and renewable energy options to avoid detrimental effects, confronting us with the need for more integrated approaches to their assessment.

The yellow cluster, which includes "decarbonization," "supply chains," and "energy systems," highlights LCA's contribution to the assessment of supply chains and energy transitions. We see a shift here toward broad and complex scales, not just based on a single sustainable process but also with interconnectedness between production, distribution, and consumption. This systemic approach aligns LCA with multi-level governance frameworks, which are particularly relevant in industrial and energy decarbonization.

Finally, the purple cluster, which originates from elements such as the "circular economy," "eco-design," and the "construction industry," positions LCA as the methodological support for the circular economy and sustainable design strategies. This group also represents an evolution of LCA with proactive applications to measure impacts, in addition, predict and avoid them from the moment of product design and process development.

Furthermore, although the clusters are different, there are multiple interconnections that run through them, it reflects through the links between the words sustainability and LCA that are not fragmented in research but operates as an interdisciplinary and intersectoral field. The peripheral placement of the words "digital transformation" indicates emerging science fields approaching combining digital technologies with sustainability.

In short, bibliometrics has confirmed that Life Cycle Assessment has surpassed its original function as an environmental assessment tool and has become an integrative driver of environmental transformation. Through this central position, science, technology, politics, and design enter a single systematic sustainability paradigm. This central role confirms the research hypothesis while opening a map of areas of interaction, challenges, and opportunities that are redefining current sustainability.

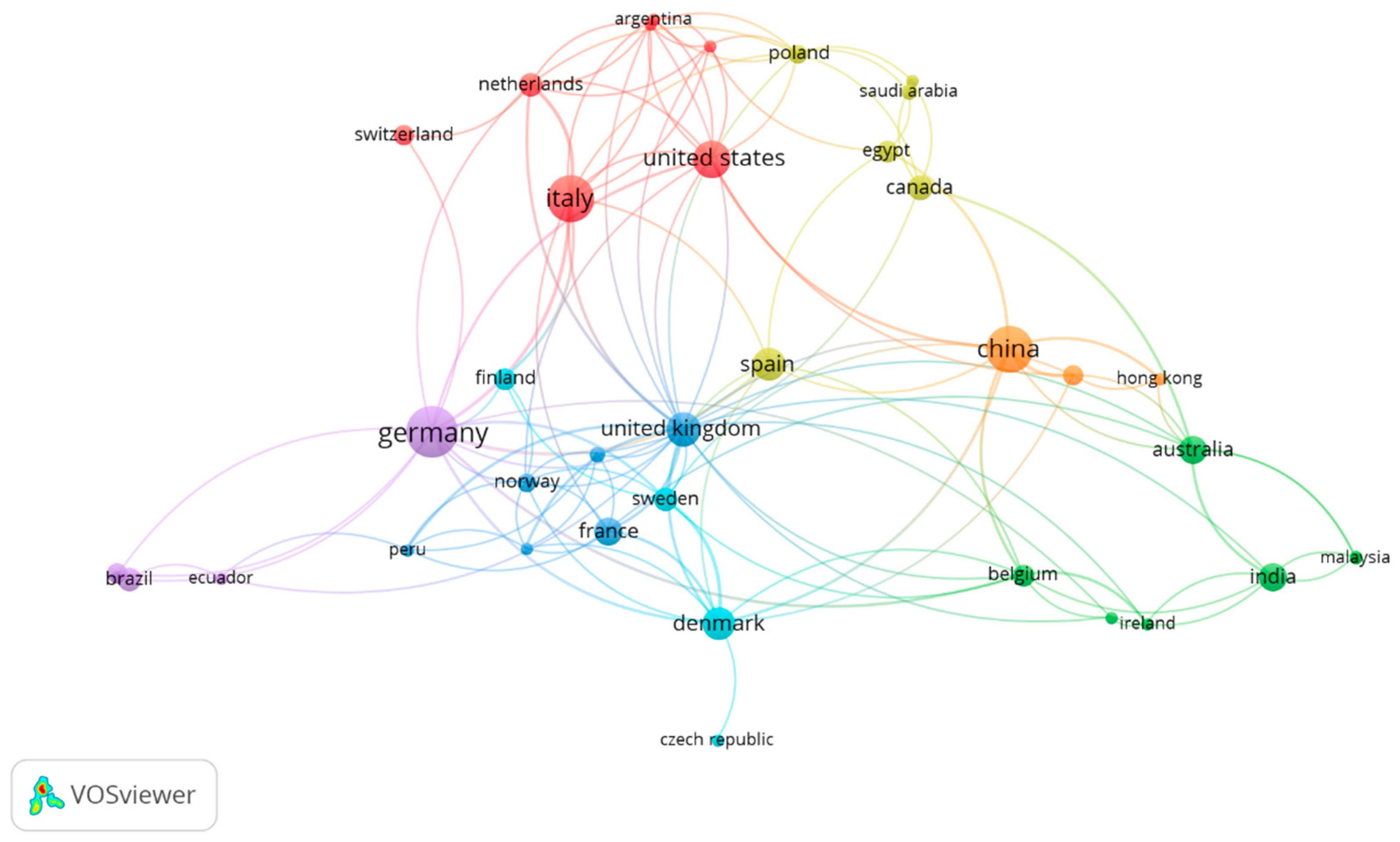

In the context of a terminological analysis, it is essential to examine the international scientific collaboration patterns defining this field. As seen in

Figure 3, the co-authorship structure is increasingly global, highlighting global dynamics in how knowledge is generated in LCA and sustainability.

The Geographic Bibliometrics Figure, created in VOSviewer, presents co-authorship relationships of the countries within the Life Cycle and Sustainable Development research field. Visualization not only expresses the intensive scientific production of each country, according to the size of the nodes but also reveals the international cooperation network (through the links between nodes), thus breaking down the overall framework of research in this field.

At the level of territorial spheres in the world: United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, China, and Spain can boast high academic output due to their size and extensive connectivity. They are the main centers of knowledge and while also playing a pivotal role in the articulation of international collaborations. This superiority implies that the dynamics of sustainability and lifecycle assessment (LCA) of research are centered on established scientific powers, which act as fields that attract researchers and their collaboration networks.

The network's polycentric structure shows, for example, that the United States maintains powerful connections with Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain but also carries out extensive cooperation with Argentina, China and Canada, so it can be said to operate in both a global and regional framework. As a result of exchanges with studies in developed and emerging regions, which suggests that the LCA model has geographic penetration, it facilitates the transmission of knowledge in areas with different environmental and economic demands.

Similarly, Germany is one of the most important European nodes, as it has close ties with France, Great Britain, Sweden, and Norway, extending to Latin American countries with connections in Brazil and Ecuador. This network is an exception for cooperation among European countries, although it also indicates expansion into Latin America driven by a mutual interest in industrial sustainability and environmental management. The presence of Peru and Ecuador in the German node strengthens the North-South flow of knowledge, which is associated with technology transfer and joint projects on sustainable development and biodiversity.

As a central hub in Asia, China is closely linked to Australia, Hong Kong, India, and Malaysia, as reflected in these connections. This network represents a collaborative Asia-Pacific pact and is likely a response to the exponential growth of environmental policy research among emerging economies, which must address common challenges such as pollution, climate change, and rapid urbanization. China's interaction with the United States and Spain demonstrates that they are also already part of global sustainability research networks, at least partially overcoming geopolitical and linguistic barriers.

An important aspect of the network is that it presents the United Kingdom as a hub, connecting with almost all clusters, from Germany and France to Spain, Denmark, India, and Australia. This position as a scientific intermediary provides the United Kingdom with a connection between Europe, Asia, and Oceania, facilitating the circulation of knowledge and contributing to intercontinental networks.

Color-coded cluster analysis reveals geographic and linguistic clustering as well as thematic and strategic clustering. The red cluster, dominated by the United States and Italy, may reflect more applied forms of research; the blue cluster, led by the United Kingdom and France, reflects more European methodological or normative approaches. The green cluster, with countries such as India, Australia, Malaysia, and Ireland, points to collaboration that addresses issues arising from sustainability in the Global South and the Commonwealth economy.

Finally, the relative peripherality of countries such as the Czech Republic, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Argentina indicates limited participation in international collaborative networks. However, their footprints suggest opportunities for scientific growth and expansion.

In summary, the bibliometric map shows that research on Life Cycle Assessment and environmental sustainability is developed within a global framework characterized by multiple centers of production and collaboration. Leading countries concentrate on research and act as connecting nodes between diverse regions and scientific traditions. This pattern of international collaboration reinforces the hypothesis that sustainability, as a scientific field, is inherently interdisciplinary, transnational, and intersectoral, relying on global networks to address complex environmental problems.

In summary, the bibliometric map shows that research on Life Cycle Assessment and environmental sustainability is developed within a global framework characterized by multiple centers of production and collaboration. Leading countries concentrate on research and act as connecting nodes between diverse regions and scientific traditions. This pattern of international collaboration reinforces the hypothesis that sustainability, as a scientific field, is inherently interdisciplinary, transnational, and intersectoral, relying on global networks to address complex environmental problems.

Based on the completed bibliometric statistics, it seems reasonable to conclude that examining individual scientific collaboration networks is essential.

Figure 4 shows the peer relationships that leading scholars in the field maintain with each other, with collaboration nodes and clusters.

The figure shows the co-authorship map among the prominent authors in the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) field and environmental sustainability. This Map was generated by VOSviewer and represents the bibliometric analysis of scientific collaboration networks. It allows us to identify the most influential researchers in the area and the connections that articulate the entire academic community around this topic.

Wernet G., Bauer C., and Steubing B.'s key positions are notable, as their labels are more connected. The core of these researchers has served as a collaborative focus, thus demonstrating their responsibility regarding the production and flow of knowledge within this field. Their close connection with other authors indicates an open and collaborative research policy, which allows for integrating different disciplinary perspectives.

Within this core, there are several different groups represented in various colors. Most are small co-authorship groups around a central researcher from a single institution or country, working on specific projects but sharing standard lines of research. For example, the blue clusters, Hellweg S., Mila i Canals L., and Finnveden G.—are well known for their methodological contributions to LCA and active participation in developing international standards and guidelines. These members are consistently close to each other, pointing to a direct relationship between applied sustainability research and methodological innovation. On the other hand, the green cluster, represented in this case by Hauschild M.Z. and Rosenbaum R.K., focuses on environmental impact assessments and indicator standardization. These authors, recognized for their work with characterization and standardization frameworks, occupy a strategic position that connects the Wernet et al. core with more specific lines of research in impact modeling.

Furthermore, it is essential to mention that on the map, we find the red cluster with researchers such as Hall CAS and Lambert JG, whose contributions are aligned with energy-ecological analysis, expanding the scope of LCA to complementary disciplines such as energy systems assessment and ecological economics. This group's representation extends the scope of action between disciplines, highlighting non-traditional LCA links. The brown cluster occupies the far left of the map, place to Arashiro LT, Josa I., and Ferrer, demonstrating that the internal links within this community are more concentrated. Collaboration is likely oriented toward more specific or local interests; they may work on case studies for specific sectors such as construction or waste management. Their peripheral location indicates a weaker connection with central networks. However, this does not necessarily mean they are less important in their specialized field.

The emergence of institutional actors such as Infineon Technologies AG is also noteworthy. It demonstrates the industry's involvement in co-authorship networks, reinforcing the applicative and translational nature of the knowledge produced in LCA. This link between academia and industry reflects a growing trend toward technology transfer and the practical implementation of scientific results.

In structural terms, the network presents a longitudinal and densely interconnected configuration at its core, even with some dispersion toward the extremes. This is characteristic of consolidating scientific fields that have already achieved articulated core communities but continue to expand into new areas of application and collaboration. The coexistence of various bridges and interconnections becomes visible in the lines connecting nodes of different colors. This suggests interdisciplinary fluidity is essential in sustainability, where scientific integration is a basic requirement for addressing complex problems.

Overall, the bibliometric analysis shows that research on Life Cycle Assessment and environmental sustainability is structured around a robust, well-coordinated, collaborative core, with regional thematic networks and sectoral applications, providing national and local balance. This co-authorship pattern supports the hypothesis that LCA and its advancement as a driver of environmental change will not rely solely on scientific production per se but instead can articulate communities of practice and interdisciplinary and interinstitutional collaborative networks.

5. Discussion

The systematic review explored the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as a current instrument for environmental transformation and identified methodological trends, success factors, and barriers that were experienced from 2018 to 2024. The results indicate that sectoral applications of LCA and its conceptual and methodological approaches have undergone significant transformations over time, highlighting, once again, its central role as an instrument for operationalizing sustainable development in a wide variety of productive contexts.

The bibliometric analysis reveals that Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) connects environmental assessments and decision-making oriented toward sustainable development. This fact is evidenced by the word "life cycle assessment" high centrality and close semantic relationship with 'sustainable development' in terminological co-occurrence networks. Its central position confirms the transition of LCA from a mere analytical tool to a comprehensive framework for transforming production systems, which aligns with research such as those by Hauschild et al. (2018) regarding the expansion of Life Cycle Assessment in contemporary environmental management.

Regarding sectoral applications, these results lead to a continuing diversification, ranging from traditional sectors to complex and interconnected systems. In the energy sector, works like that of Hernández-López et al. (2024) have already evaluated renewable technologies through life cycle assessment. These methodologies include end-of-life scenarios and transportation aspects, thus demonstrating their applicability to critical points in the energy value chain. In parallel, alternative practices have also been studied in the agri-food sector such as using ozonated water to irrigate vineyards (Lago-Olveira et al., 2024). This further demonstrates the suitability of LCA for comparing sustainable innovations with conventional methods. This trend toward increasingly specific applications with a greater ability to adjust to sectoral details, only highlights once again that LCA is a highly versatile tool in sectoral transitions, however, also raises problems of intersectoral comparability that hinder the generation of interdisciplinary knowledge.

In terms of methodological innovation, there is a shift from static approaches focused on direct environmental impacts to dynamic frameworks incorporating economic and social dimensions. The progressive incorporation of digital technologies such as blockchain or digital twins, demonstrated by Figueiredo et al., represents an emerging trend that overcomes traditional Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) problems related to data availability and updating. Finally, the evolution toward Sustainability Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) reflects an attempt to coherently incorporate the three dimensions of sustainable development, even though significant methodological problems remain, especially regarding quantifying social impacts and balancing incommensurable categories. This is illustrated by recent observations by Troullaki et al. on the epistemological barriers in integrated sustainability research (2021).

Among the most notable findings is the progressive adoption of LCA studies in certain regions, thus overcoming the initial methodological universalism and moving toward approaches that consider specific geographic, sociocultural, and economic contexts. This recent shift is fueled by increasing evidence of the importance of local factors in determining environmental impacts, especially in areas such as drought and species diversity, where the specific situation of each environment significantly modifies the results. However, this regional approach introduces new challenges regarding local-level data availability and comparability between studies conducted in different contexts.

Regarding the restrictions and challenges, the review conducted in Ireland identifies persistent methodological inconsistencies that only hamper comparisons across studies. Bishop et al. (2021) found divergences in aspects such as the definition of functional units, system boundaries, and impact assessment methods. These differences hamper knowledge integration and can lead to contradictory conclusions about the sustainability of specific products or processes. Furthermore, the increasing complexity of models and the integration of multiple dimensions present significant challenges for effectively communicating results to non-specialist decision-makers, potentially limiting their practical impact.

Regarding the impact of LCA on environmental policies and decision-making, the results show an evolution from an almost exclusively academic approach to the gradual adoption of inspection reports, regulatory adjustments, company reports, and even systems for verifying results. The documentation by Röck et al. (2021) on incorporating the lifecycle approach into formal frameworks such as the European Green Deal exemplifies LCA's progress towards an evidence-based policy tool. However, a significant gap persists between the methodological rigor required by scientific and technical assessments and the simplicity required for its practical use in decision-making, leaving some questions about the most appropriate compromises between accuracy and applicability.

Among the convergences identified in the study's analysis, there were only three: whether the lifecycle paradigm should be used to avoid or shift environmental burdens from one stage to another, the adoption of standardized impact sets, and the basic methodological structure established by international standards. These convergences provide an everyday basis for expanding knowledge and sharing certain established practices. Instead, the most significant differences center on aspects such as the choice of valuation methods, the definition of the system's operational boundaries, and the integration of socioeconomic aspects, highlighting the normative nature of methodological decisions in the field of LCA.

This research has demonstrated the contribution of life cycle assessment (LCA) to SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production) through its ability to identify unsustainable production patterns and its relevance in optimizing production processes. These conclusions are consistent with the "Life Cycle Assessment in European Environmental Policy" presented by Sanyé-Mengual & Sala (2022), which established that LCA could be used for countries integrated into an international system and the credible performance of the different products or agents involved in this. The contribution of LCA to SDG 13 (Combating climate change) materializes in the rigorous calculation of greenhouse gas emissions throughout the value chain, which provides information for designing more effective mitigation strategies. It also helps SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by stimulating innovation towards sustainability, especially in sectors such as construction and infrastructure where there are increasingly more alternatives such as that of Paturu & Varadarajan (2024), which demonstrated our usefulness in contrasting production-service systems in urban contexts.

The theoretical implications of findings such as these emphasize the need for future methodological frameworks that better consider the multiple dimensions of sustainability, effectively bringing together disciplines rather than the approach taken until today. In turn, the conclusions suggest the need to design approaches that explicitly examine how socio-ecological systems interrelate and the challenges they face, taking a broader view of the dynamic and complex challenges of sustainability. In practical terms, the results indicate the importance of simplifying the application of LCA to make it more accessible to organizations with limited resources and technical capabilities, creating communication formats that allow for greater accessibility without compromising methodological rigor.

Future research should address methodological harmonization to improve comparability across studies, develop more robust and contextualized social indicators for LCA, and effectively integrate LCA with other conceptual frameworks such as the circular economy and ecosystem services assessment. In turn, it would be worthwhile to systematically analyze the institutional and organizational factors that facilitate or hinder the application of LCA as an environmental management tool in different geographic and economic contexts.

In summary, the systematic review confirms the role of LCA as a facilitating tool primarily for changing our environment, evolving from a mere analytical technique to a comprehensive system that provides information for sustainable decisions. However, fully unleashing its potential requires addressing significant challenges regarding methodological consistency, integration of multiple dimensions, and effective communication of results. These changes are crucial to strengthening its contribution to achieving the SDGs and transitioning to more resilient and regenerative economic models.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review allowed us to analyze the Life Cycle Assessment tool and its status for environmental transformation from 2018-2024, demonstrating how it has established itself as an essential tool for operationalizing sustainability in diverse contexts. The findings highlight the evolution of LCA from a purely evaluative approach to the adoption of a detailed framework for sustainability-oriented decisions that, in short, meet the overall objective of critically examining its contribution to changes in production systems.

The systematic review's analysis has addressed the central question: What influence has Life Cycle Assessment research had on the ecological transformation of production systems, and what methodological or institutional factors determine its effectiveness as a tool for sustainability?

Therefore, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) today is no longer just a comprehensive tool for examining a product's environmental impact but also a means of systemic change that can catalyze comprehensive transformations in production systems.

The transformation materializes in three main dimensions: The first that considered Methodological Transformation, indicates a shift from a vision based purely on the environment in a temporal space (2018-2019) to more dynamic and integrative frameworks that incorporate all economic, social, and environmental areas of the LCA (European Buildings Performance Survey, 2022-2024) with more comprehensive evaluation results and contextualized policies. The second, Applicative Transformation shows how LCA moved from a traditional sectorized space based on environmental impact to more interconnected sectors, from individual to complex systems—for example, renewable energy, sustainable construction, bioeconomy, and circular models. The third transformation was institutional, adopting international LCA regulatory frameworks (European Green Deal, SDGs) and becoming part of public policies, corporate reporting, and certification systems.

Regarding methodological convergences and divergences in sectoral applications, the analysis reveals significant similarities, such as the widespread adoption of the lifecycle paradigm, which has made it possible to avoid the displacement of environmental burdens; the use of homogeneous impact categories implemented by international standards; and the formalized and accepted methodological basis of ISO 14040 and 14044. The divergences are found in the definition of functional units (significant discrepancies between sectors make intersectoral comparison difficult), system boundaries (inconsistencies in the inclusion and exclusion of lifecycle stages), and impact characterization methods (in the selection of impact categories and characterization factors). Furthermore, they also reveal similarities in integrating socioeconomic aspects (different approaches are used, but there is no consensus on their methodology). These differences are challenging when comparing studies and achieving systematic knowledge; they are a critical barrier to generalizing results and conducting quantitative analyses across multiple studies.

The question of the effectiveness of LCA and its integration of sustainability dimensions does not lead to the conclusion that the introduction of LCA in comprehensive contexts such as S-LCA (Sustainability Life Cycle Assessment) has achieved the goal, just only partial progress and has yet to resolve issues. Partial achievements include the development of conceptual frameworks that incorporate fuzzy logic to address uncertainties, the use of participatory methods to incorporate stakeholder perspectives into assessments, and progress in quantifying social impacts through approaches such as social footprinting. Critical limitations include dimensional incommensurability, in which fundamental difficulties persist in coherently integrating environmental, economic, and social aspects; the availability of social data shows structural limitations in the availability and quality of technology-specific social data; The subjectivity in weighting demonstrated by the lack of consensus on criteria for submitting direct alternatives with the same systematic rigor that does not require collaboration with oppositions; and finally the difficulties of complex communication where it is not possible to summarize and weigh multidimensional results for communication that decision-makers can directly use.

Several factors must work together among the factors that determine the effectiveness of LCA as an instrument for environmental transformation. This can encompass both methodological and institutional areas. In the first field of study, there are four fundamental impediments: the lack of uniformity, highlighted by the lack of protocol standards by sector, which limits the possibility of comparing studies with each other; the growing complexity due to the inclusion of multiple dimensions, which makes it much more technically and computationally difficult; the lack of data, often abysmal, especially in emerging economies where the lack of primary information is critical for the robustness of assessments; and the difficulties faced in transparently communicating doubts and differences inherent in LCA models. At the same time, institutional factors pose equally demanding barriers: the persistent gap between technical and political knowledge reflects a fundamental incompatibility between the methodological rigor required for scientifically valid assessments and the simplicity of decision-making in individual second-part reports. Narrow technical capabilities are significant access barriers for organizations with limited human and financial resources; institutional resistance, embodied in organizational inertia, hinders the adoption of comprehensive approaches both in the long and short term; and geographical inequality, where scientific and technical capabilities are naturally concentrated in industrialized countries, thus accentuating the development of LCA inequalities worldwide.

LCA has contributed primarily through SDG 12 (Sustainable Production and Consumption), which allows for the identification of unsustainable patterns and optimization of production processes; SDG 13 (Climate Action), through the systematic quantification of greenhouse gas emissions along entire value chains; and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), by catalyzing sustainability-oriented innovations, especially in resource-intensive sectors. This overlap confirms the potential of LCA as a tool for operationalizing the 2030 Agenda, considering products and processes.

It will be valuable to systematically explore the institutional and organizational factors that facilitate or hinder its implementation in different contexts. This topic has been addressed little at present but could well be essential to understanding its effectiveness as a transformational tool. In the future, the harmonization of methodologies should also be addressed to improve the comparability of studies. Although this is barely noticeable in our current academic literature, it is important to understand if we want to know whether it produces real effects on the development of social indicators for sustainability.

LCA has demonstrated its transformative potential as a driver of change toward more sustainable production systems. However, fully realizing this potential requires addressing fundamental challenges operating simultaneously on three interrelated fronts: the technical front, where it is necessary to harmonize methods and develop easily accessible tools that overcome barriers to LCA implementation (without neglecting strictly scientific approaches); the institutional front, which requires the planned development of human and technical competencies to carry out assessments and action frameworks that facilitate the adoption of LCA in public and corporate policies; and the epistemological front, which poses a conceptual challenge: moving toward truly comprehensive approaches that overcome current disciplinary barriers and address the inherent complexity of contemporary socio-ecological systems from a broader perspective. Only the strategically designed convergence of these diverse multidimensional efforts will ultimately consolidate LCA as an essential tool on the path toward development models that effectively combine economic prosperity, social equity, and ecological recovery. Thus, it contributes to the substantial achievement of the 2030 Agenda and the fulfillment of global climate commitments of contemporary environmental urgency.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D.A.L. and E.B.A.; methodology, D.A.L.; software, D.A.L.; validation, D.A.L. and E.B.A.; formal analysis, D.A.L. and E.B.A.; investigation, D.A.L. and E.B.A.; resources, D.A.L. and E.B.A.; data curation, D.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation D.A.L.; writing—review and editing, E.B.A.; visualization, E.B.A.; supervision, D.A.L.; project administration, D.A.L.; funding acquisition, D.A.L. and E.B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad César Vallejo, grant number P-2022-174 and The APC was funded by Universidad César Vallejo.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was exempted from ethical review and approval because it is not applicable as it does not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Vice-Rectorate for Research at César Vallejo University for the administrative and technical support received during the research and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Apostolopoulos, V., Mamounakis, I., Seitaridis, A., Tagkoulis, N., Kourkoumpas, D. S., Iliadis, P., Angelakoglou, K., & Nikolopoulos, N. (2023). An Integrated Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing Approach Towards Sustainable Building Renovation Via a Dynamic Online Tool. Applied Energy, 334(October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R., & Santos, D. F. L. (2020). Sustainable business models and eco-innovation: A life cycle assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 121954. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G., Styles, D., & Lens, P. N. L. (2021). Environmental performance comparison of bioplastics and petrochemical plastics: A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) methodological decisions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 168, 105451. [CrossRef]

- Brandão, M., Weidema, B. P., Martin, M., Cowie, A., Hamelin, L., & Zamagni, A. (2024). Consequential Life Cycle Assessment: What, Why and How? (M. A. B. T.-E. of S. T. (Second E. Abraham (Ed.); pp. 181–189). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Ceraso, A., & Cesaro, A. (2024). Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of municipal solid waste management systems: a review. Journal of Environmental Management, 368, 122143. [CrossRef]

- Cremiato, R., Mastellone, M. L., Tagliaferri, C., Zaccariello, L., & Lettieri, P. (2018). Environmental impact of municipal solid waste management using Life Cycle Assessment: The effect of anaerobic digestion, materials recovery and secondary fuels production. Renewable Energy, 124, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. H., & Ng, S. T. (2015). A social life cycle assessment model for building construction in Hong Kong. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 20(8), 1166–1180. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, K., Hammad, A. W. A., Pierott, R., Tam, V. W. Y., & Haddad, A. (2024). Integrating Digital Twin and Blockchain for dynamic building Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Journal of Building Engineering, 97(October), 111018. [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G., Hauschild, M. Z., Ekvall, T., Guinée, J., Heijungs, R., Hellweg, S., Koehler, A., Pennington, D., & Suh, S. (2009). Recent developments in Life Cycle Assessment. Journal of Environmental Management, 91(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Gottinger, A., Ladu, L., & Blind, K. (2023). Standardisation in the context of science and regulation: An analysis of the Bioeconomy. Environmental Science and Policy, 147(October 2022), 188–200. [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J. B., Heijungs, R., Huppes, G., Zamagni, A., Masoni, P., Buonamici, R., Ekvall, T., & Rydberg, T. (2011). Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(1), 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2), e1230. [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M. Z., Rosenbaum, R. K., & Olsen, S. I. (Eds.). (2018). Life Cycle Assessment (1st ed.). Springer Cham. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, D.-A., Vega-De-Lille, M. I., Sacramento-Rivero, J. C., Ponce-Caballero, C., El-Mekaoui, A., & Navarro-Pineda, F. (2024). Life cycle assessment of photovoltaic panels including transportation and two end-of-life scenarios: Shaping a sustainable future for renewable energy. Renewable Energy Focus, 51(October). [CrossRef]

- Hicks, A. (2023). Using counterintuitive sustainability examples in teaching life cycle assessment: A case study. RESOURCES CONSERVATION & RECYCLING ADVANCES, 19. [CrossRef]

- Iofrida, N., De Luca, A. I., Strano, A., & Gulisano, G. (2018). Can social research paradigms justify the diversity of approaches to social life cycle assessment? The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23(3), 464–480. [CrossRef]

- Kalbar, P. P., & Das, D. (2019). Advancing life cycle sustainability assessment using multiple criteria decision making. In Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Decision-Making: Methodologies and Case Studies (Issue Lcc). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Lago-Olveira, S., Cancela, J. J., Tubío, M., Moreira, H. F., Moreira, M. T., & González-García, S. (2024). Environmental benefits of ozonated water for sustainable grapevine disease control: A life cycle and carbon sequestration analysis. JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION, 478. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E., Martín, A. J., Mitchell, S., Nabera, A., Santos, L. F., Pérez-Ramírez, J., & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. (2024). The need to integrate mass- and energy-based metrics with life cycle impacts for sustainable chemicals manufacture. Green Chemistry, 26(17), 9300–9309. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A., Martins, I. S., Kastner, T., Plutzar, C., Theurl, M. C., Eisenmenger, N., Huijbregts, M. A. J., Wood, R., Stadler, K., Bruckner, M., Canelas, J., Hilbers, J. P., Tukker, A., Erb, K., & Pereira, H. M. (2019). Increasing impacts of land use on biodiversity and carbon sequestration driven by population and economic growth. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3(4), 628–637. [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, G. A., Takahashi, T., & Lee, M. R. F. (2018). Framework for life cycle assessment of livestock production systems to account for the nutritional quality of final products. Food and Energy Security, 7(3), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Moutik, B., Summerscales, J., Graham-Jones, J., & Pemberton, R. (2023). Life Cycle Assessment Research Trends and Implications: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(18). [CrossRef]

- Niero, M., & Kalbar, P. P. (2019). Coupling material circularity indicators and life cycle based indicators: A proposal to advance the assessment of circular economy strategies at the product level. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 140(July 2018), 305–312. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Mcdonald, S., … Mckenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, 372. [CrossRef]

- Paturu, P., & Varadarajan, S. (2024). Assessing environmental sustainability by combining product service systems and life cycle perspective: A case study of hydroponic urban farming models in India. Science of the Total Environment, 927(April), 172232. [CrossRef]