1. Introduction

Given the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions drastically, it is essential to change our transport systems radically, especially by reducing individual car use and supporting the uptake of low-carbon and/or active modes of transport, such as public transport, cycling and walking (Climate Change Committee, 2023; Jaramillo et al., 2022). Recently, a range of light, electric transport modes have emerged in academic and policy discussions as potential avenues for sustainable urban mobility, such as electric cargo bikes.

Electric-assist cargo bikes, or e-cargo bikes, are bicycles designed to carry goods or passengers, either at the front or at the back of the bicycle. In this paper, we consider e-cargo bike use in domestic settings. In the UK, e-cargo bikes fall under the ‘Electric Assisted Pedal Cycle’ regulation with a motor assistance of a maximum continuous power of 250w, which only occurs when pedalling up to speeds of 25 km/h (GOV.UK, 2024). Their batteries typically have a published range of 50-80 km (Narayanan & Antoniou, 2022). E-cargo bikes are popular as a van replacement for business and logistics use (Cairns & Sloman, 2019). They are also well suited to household use with their capacity to transport goods (e.g. groceries) and/or passengers, making them ideal low-carbon and active alternatives to cars, particularly for families (Marincek et al., 2024). Despite their growing popularity in countries such as Switzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands, the adoption of e-cargo bikes remains relatively low in the UK – with 4,000 sold in 2022 for both logistics and domestic use (Garidis, 2023).

The limited adoption of e-cargo bikes may stem from negative perceptions and beliefs held by individuals who have not yet used these modes, referred to as imagined barriers in this study. Research has shown that imagined barriers often diminish when individuals gain direct experience with transport modes (Joachim et al., 2018). This highlights the value of trial programs in overcoming imagined barriers to transport modes. Trials are interventions designed to encourage behavioural change with limited risk and uncertainty (Strömberg et al., 2016). Our study examines how trial loans may influence the barriers to adopting sustainable modes such as e-cargo bikes. This is particularly crucial considering the urgent need to shift towards more sustainable urban mobility.

This study contrasts imagined and experienced barriers to e-cargo bike adoption by analysing the views of two groups with different knowledge and experience of e-cargo bikes. First, we examine the barriers to e-cargo bike adoption as imagined by English individuals who do not use e-cargo bikes. These perceptions were collected through responses to an open-ended question in a representative national survey on e-micromobility (n=484). Then, we compare these imagined barriers with the experienced barriers of individuals (n=49) who participated in trial loans of e-cargo bikes in the suburbs of Leeds, Oxford and Brighton, captured through semi-structured interviews. Participants had access to e-cargo bikes directly at home for a month, similar to a long-term lease model.

The research question guiding this study is: What are the imagined barriers to e-cargo bike adoption, and how do they compare to actual barriers experienced by e-cargo bike trial participants? By comparing imagined and experienced barriers, we seek to uncover how such trials can effectively address barriers to e-cargo bike adoption and how barriers may differ with experience. This can, in turn, inform policy interventions that aim to support the adoption of sustainable transport modes such as e-cargo bikes.

Next, we present our theoretical background on barriers to cycling and trials.

Section 3 outlines our mixed-method approach combining qualitative survey responses and interview data.

Section 4 presents our results on barriers to e-cargo bike adoption. We discuss our findings, considering the potential of trials to overcome barriers in

Section 5 and conclude in

Section 6.

2. Theoretical Background

This section first reviews empirical studies on barriers to cycling adoption, as these may be relevant to e-cargo bike adoption. Second, we discuss trials in relation to barriers.

2.1. Barriers to E-(Cargo) Cycling

Scholarly work has extensively examined barriers to the adoption of cycling, and to a lesser extent, the adoption of e-bikes and e-cargo bikes specifically. There are numerous barriers specific to short-term sharing schemes (e.g. Teixeira et al., 2023; Hess & Schubert, 2019), but these fall outside the scope of this study which focuses on trials that mimic long-term lease models of use. In the review of scholarship on cycling, we identified three key sets of barriers to e-cargo cycling: spatial, material and societal barriers.

A first set of barriers relates to space. The lack of suitable infrastructure, both for riding and parking is widely discussed (Bourne et al., 2020; Dill & Rose, 2012; Jones et al., 2016; Marincek et al., 2024). Moreover, there are concerns about feeling unsafe among other traffic (mostly motorised vehicles such as cars), which is especially prominent when carrying children (Marincek et al., 2024). These barriers tend to discourage cycling in general (Félix et al., 2019).

A second set of barriers concerns material elements of e(-cargo) bikes. This includes the vehicle and its electric assistance. Their relatively high cost is a barrier, which results in fear of theft, as well as their bulkiness, which makes them hard to manoeuvre (Bourne et al., 2020; Dill & Rose, 2012; Jones et al., 2016; Marincek et al., 2024; Melia & Bartle, 2021). Battery-related issues are also barriers, such as so-called ‘range anxiety’ or impracticality of charging (Bourne et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2016).

Finally, a third set of barriers relates to the perceptions and images of users. Just like cycling, electric and/or cargo cycling can reflect negative associations. Indeed, several studies found evidence of stigma around e-bikers, who are perceived as ‘cheating’ (Jones et al., 2016; Popovich et al., 2014). In the Dutch context, users of cargo bikes have been associated with gentrification and ‘green leftist yuppy’ stereotypes (Boterman, 2020).

These barriers can differ across different socio-demographic groups and geographical contexts (Harms et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016). For example, a study of non-users showed that women would find it more difficult than men to ride an e-cargo bike (Lahon & Engelen, 2024). Grudgings et al. (2018) also demonstrate that in low-cycling contexts, women tend to cycle less. However, the gender gap in use is smaller than expected in several UK-based e-bike studies (Melia & Bartle, 2021; Philips, Brown, et al., 2024). Differences in barrier perceptions also emerge between users and non-users, as shown by Hess & Schubert’s (2019) study on shared e-cargo bikes in Switzerland and Speak et al.’s (2023) work on shared e-scooters in the UK. Safety especially stands out as a key barrier for non-users, while users discuss conflicts with other modes in public space, due to the necessity of sharing the infrastructure (Speak et al., 2023).

2.2. Trials and Barriers

‘Soft’ behavioural interventions have gained currency in transport research as a way to encourage people to shift to more sustainable travel habits, in contrast with ‘hard’ measures such as infrastructure change (Cairns et al., 2008; Pan & Ryan, 2024). These interventions often aim to address psychological and economic barriers to behavioural change (Cairns et al., 2008). Central to these interventions are trials, which allow individuals to test alternative transport modes through e.g. free public transport passes (Abou-Zeid & Ben-Akiva, 2012; Thøgersen, 2009) or temporary bicycle loans (Strömberg et al., 2016), thereby reducing the inherent uncertainty of behavioural change. While trials effectively eliminate cost barriers, they mainly influence people who were already inclined to change (Abou-Zeid & Ben-Akiva, 2012). Nonetheless, Strömberg and colleagues (2016) highlight that small-scale trial experiments create observable examples of sustainable travel behaviours, influencing broader social networks and normalising sustainable travel choices.

Trial programs can also be understood through the lens of innovation studies. Rogers’ (1995) theory of the diffusion of innovations points to the role of trials in reducing uncertainty and providing experiences. Trials can also be seen as protected spaces where sustainable transport innovations develop and stabilise, referred to as niches in transitions studies (Smith & Raven, 2012). These can be created, protected and managed through strategic niche management (Markard et al., 2012). Experimentation with innovations such as pilot programs or living labs is a key mechanism to niche creation and development (Kemp et al., 1998; Sengers et al., 2019). Overall, trials have potential to change individual behaviours but also to foster societal transitions more broadly.

Several studies have investigated bicycle trials as a strategy to disrupt long-term mobility habits and increase the likelihood of adopting bicycles. Cairns et al. (2017) observed that 6-8 weeks e-bike loans to 80 employees in Brighton led to 38% saying they would cycle more in the future and at least 70% expressing interest in e-bike access. Moser et al. (2018) studied a Swiss e-bike/car key exchange program where two-week e-bike trials weakened participants’ long-term habitual associations with car use. In Norway, Fyhri et al. (2017) found that even 2–4-week e-bike loans increased the willingness to purchase e-bikes, although infrastructure limitations remained a persistent external barrier. Fewer studies focused on cargo bike trials, with Bjørnarå et al.’s (2019) Norwegian study that found increased cycling and decreased car use in parents with children and in Sweden, where cargo bike trials opened up possibilities for car-free lifestyles for many participants (Börjesson Rivera & Henriksson, 2014).

3. Methodology

This section outlines the methodology used for data collection and analysis. This paper adopts a mixed-method data collection approach that utilises two qualitative data sources. We combine survey responses — to collect the barriers as imagined by individuals who have not used an e-cargo bike, with interview data — to understand the barriers as experienced by people who have used an e-cargo bike as part of trial loans. By integrating these two datasets, we combine the larger audience of survey responses with the depth of interview data. We then analysed the data qualitatively through thematic analysis.

These two datasets were collected as part of a UK-based research project (ELEVATE), and the project design and data collection methods are presented in detail in Philips, Azzouz, et al. (2024). Ethical approval for both interviews and surveys was obtained from the University of Leeds Ethics Committee (Reference FREC 2023-047701198).

3.1. Dataset 1. Qualitative Survey Comments – Imagined Barriers

The first dataset, qualitative responses to an open question to capture imagined barriers from individuals who have not used an e-cargo bike, was collected from an online survey of 2000 English adults, which aimed to understand ownership, use of and attitudes towards e-micromobility. The survey was designed as part of the ELEVATE project, and the market research company Yougov Plc was commissioned to collect representative data in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, social class and region. Some quantitative survey results are available in Philips et al. (2025). As well as sections collecting socio-demographics and transport data, three survey sections investigated use, access and attitudes towards e-bikes, e-cargo bikes and e-scooters successively. At the end of the section on e-cargo bikes, respondents were asked if they would like to make any comments about e-cargo bikes.

Figure 1 presents the information provided in the survey about e-cargo bikes.

This paper uses the responses from the sub-set of respondents who never used an e-cargo bike (n = 1908), to this optional open-ended question (n = 484). While our quantitative findings (reported elsewhere) provided objective insights into the level of interest, attitudes and some barriers for those individuals at the time of asking, the approach of this paper focuses on understanding how subjective opinions (i.e. imagined barriers) might affect the adoption of e-cargo bikes. Open-ended questions can capture insights that were not covered by closed questions, thereby reducing the risk of missing important issues (O’Cathain & Thomas, 2004). Responses to open-ended questions tend to be more biased than those to closed-ended questions, with people with the most negative views more likely to comment (Rodrigue et al., 2024). As such, this dataset is not intended to be representative of public perceptions, but rather to explore the views of a vocal minority eager to express their opinions about e-cargo bikes.

While the overall sample was representative of the English population, there was some tendency in respondents to the open-ended question. Adults over 50 (31% commented) were more likely than adults under 35 (17% commented) to leave a comment. Gender differences were not significant, with 26% of men commenting compared to 24% of women.

3.2. Dataset 2. Interviews – Experienced Barriers

Second, to capture the barriers

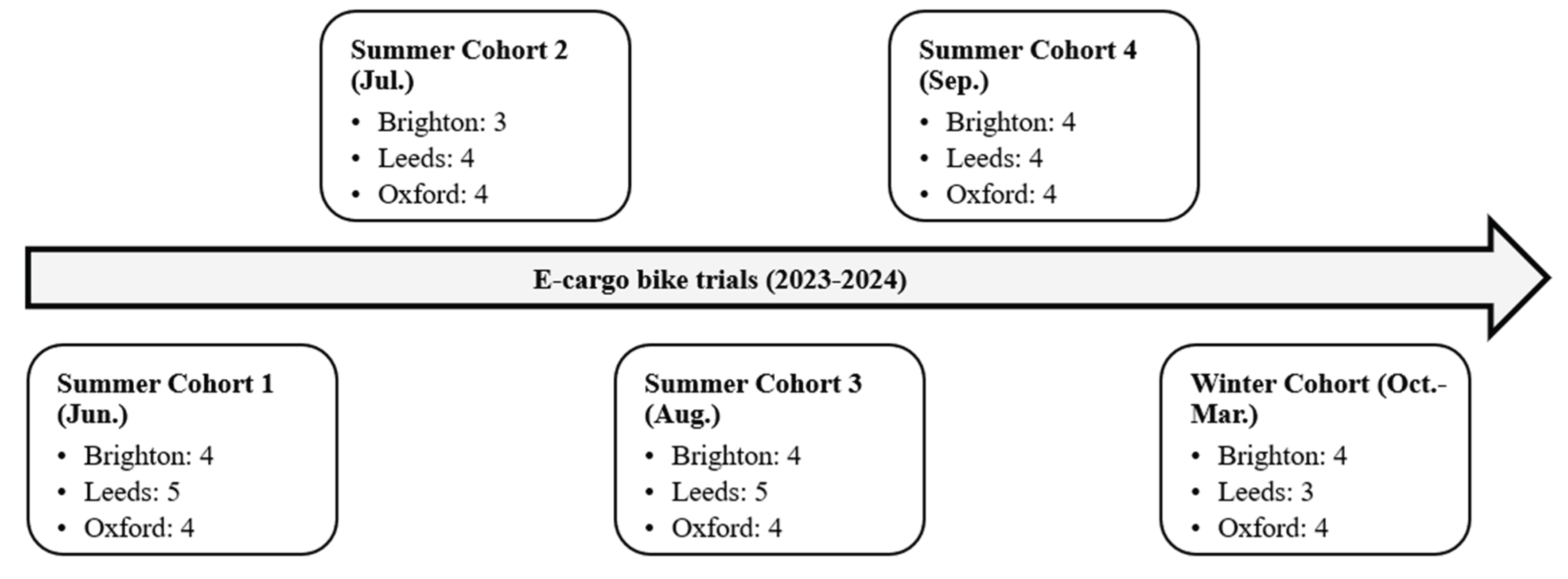

experienced by people who have used e-cargo bikes, we conducted interviews with people in households that had participated in a e-cargo bike research trial. Between June and September 2023, 49 households were lent an e-cargo bike for one month each. They lived in the suburbs of three UK cities: Preston Park and Hove Park (Brighton & Hove), Guiseley, Otley and Yeadon (Leeds), and Kennington (Oxford). Leeds has low cycling rates, comparable to the rest of England, whereas Oxford is known for its high levels of cycling, and Brighton is intermediate. Among the households, 11 were loaned an e-cargo bike for a longer period in the winter between October 2023 and March 2024 (see

Figure 2). Participating households were interviewed multiple times during their trial periods. The interviews collected information on participants’ expectations, hopes, experiences, concerns and perceptions regarding the adoption and use of e-cargo bikes. They also explored participants’ willingness to use and purchase an e-cargo bike in the future, as well as the potential impact on their car usage. We recorded all interviews with the participants’ consent and transcribed them for analysis. This study considers a total of 108 interviews. The anonymised dataset is available from the UK Data Service’s online data repository (Cass et al., 2024).

3.3. Data Analysis

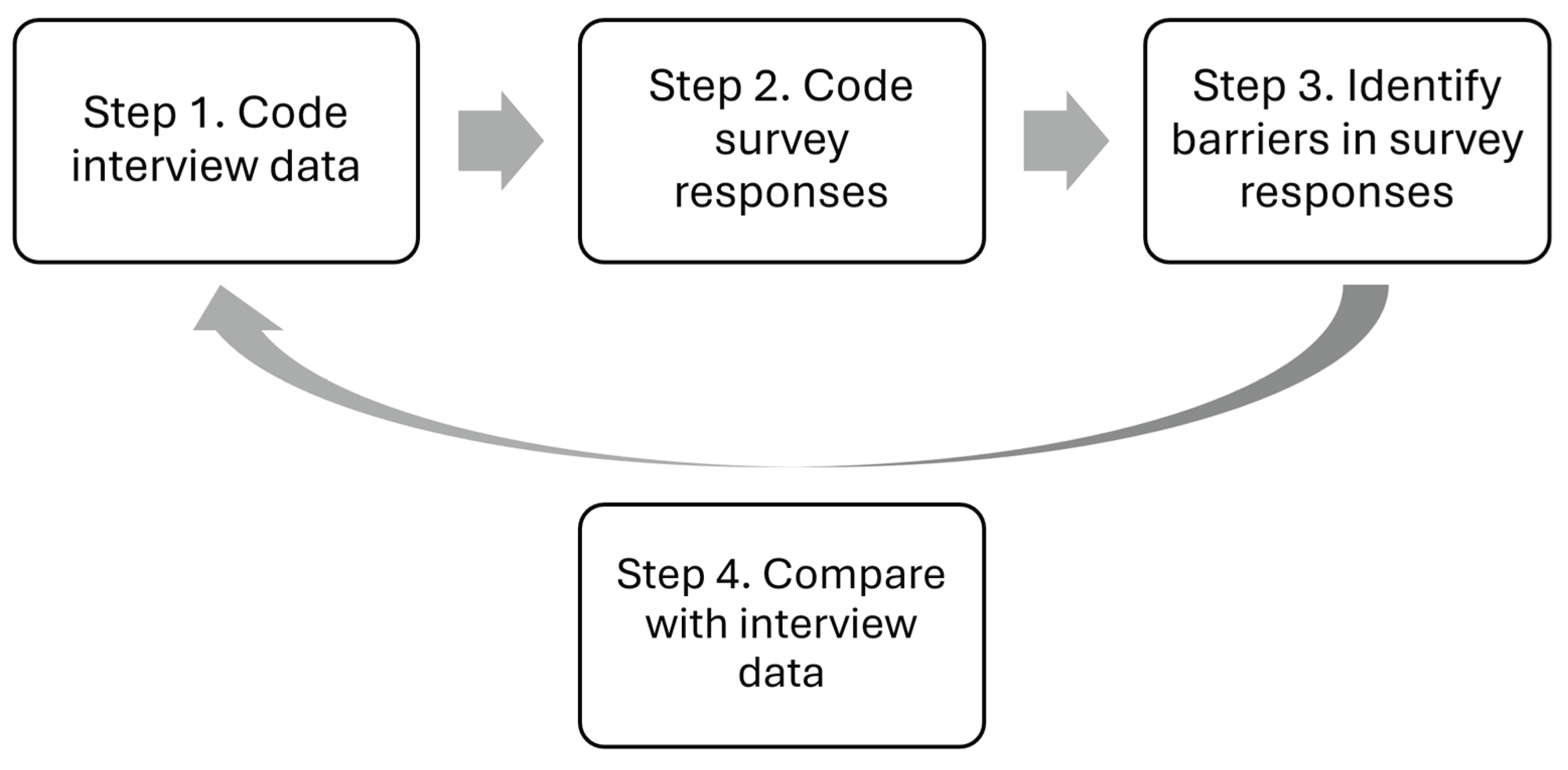

We analysed the comments on perceived barriers from survey respondents and interview data on experienced barriers from trial participants following a qualitative thematic approach, in four steps summarised in

Figure 3. First, we analysed interviews with codes developed deductively by the project team based on the interview questions. We also included inductive elements in the initial stage of coding. Four project members were involved in coding, using the NVivo 14 collaborative version. Intercoder reliability was guaranteed through test coding and co-coding at different stages of the coding process.

Second, based on the interview coding framework, we developed a new coding framework with codes relevant to the qualitative survey comments. These guided the deductive coding of the survey entries. In addition, inductive coding has been used to capture elements that the existing interview framework did not address. Third, we grouped the survey codes under the three sets of barriers, informed by our literature review on barriers to e-(cargo) cycling in

Section 2.1.

Fourth, we matched interview codes relevant to the themes that emerged from our analysis of survey responses (see

Table 1). We then compared interview and survey data per theme to uncover imagined and experienced barriers to e-cargo bike adoption.

4. Results

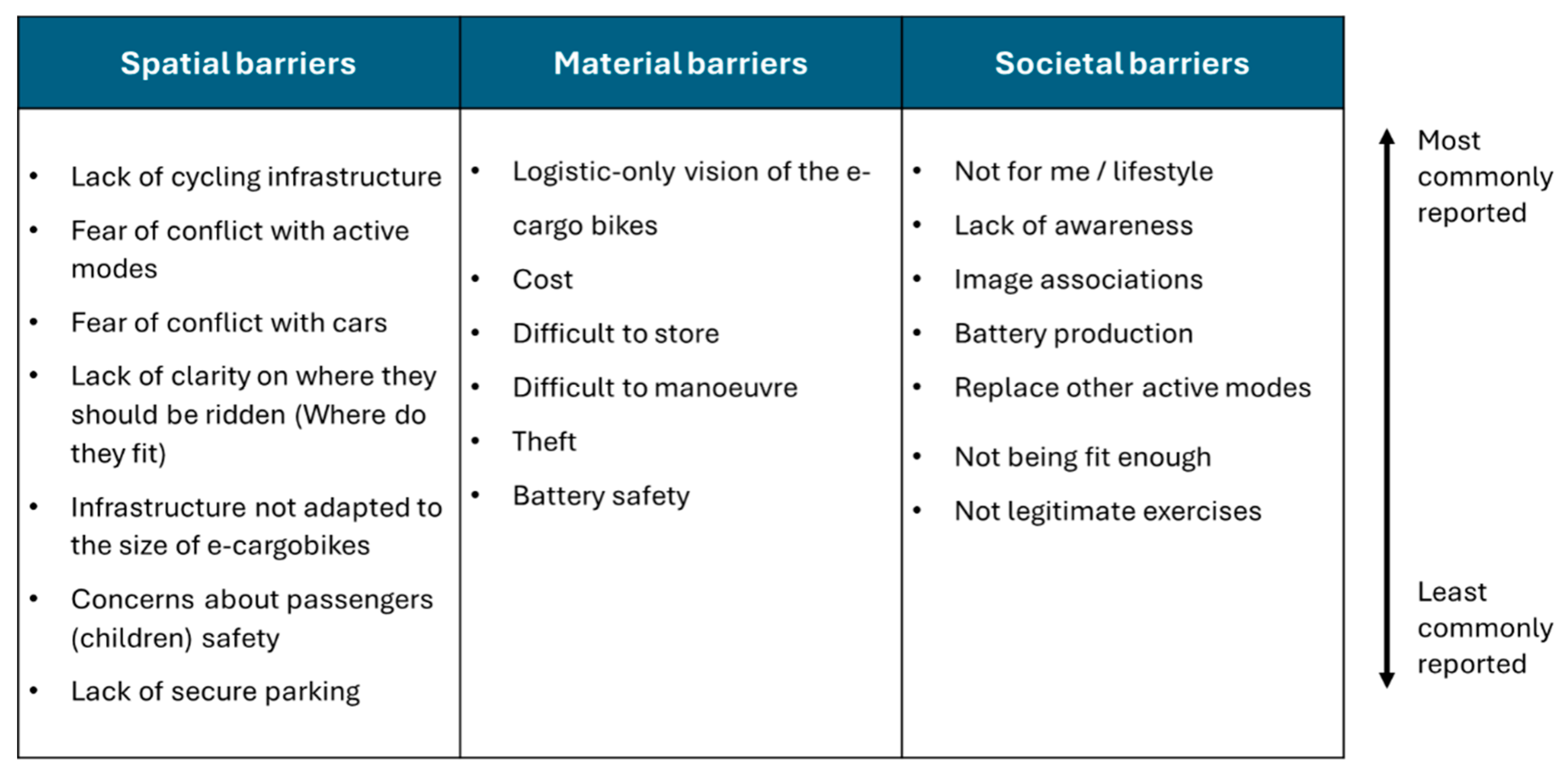

This section presents our findings on the barriers to e-cargo bike adoption as imagined by survey respondents, in comparison with the barriers as experienced by e-cargo bike trial participants on three distinct, but related sets of barriers uncovered in our literature review: Spatial (4.1.), Material (4.2.) and Societal (4.3.) barriers. An overview of the barriers found in the survey is presented in

Figure 4. These barriers form the building blocks of our analysis and interview data is then used in the next three sections to contrast these results.

4.1. Spatial Barriers

The first set of barriers to e-cargo bike adoption found in our research data are spatial. This subsection presents concerns regarding the infrastructure needed for e-cargo bike use, as well as the spatial conflicts and subsequent safety challenges perceived by survey respondents, compared with how they are experienced by trial participants.

4.1.1. Infrastructure

A recurring concern for survey respondents is the lack of infrastructure for e-cargo bikes specifically or for cycling in general. Some had positive views around these bikes but insisted that government investment on high quality cycling infrastructure needs to happen first. On that aspect, survey respondents compared the UK with the Netherlands, as exemplified by this quote: “This isn’t Holland. This country (...) doesn’t have the system in place or the space on busy roads for cargo bikes. We are making our roads bigger and faster and don’t even have proper, countrywide, safe cycle lanes!” (Female, 65-69, survey).

This concern about cycling infrastructure was also shared by some trial participants. Although some found it “totally doable to move around” (Brighton, Female, 30-34, int.), others noted that “the cycle infrastructure doesn’t quite marry up to the quality of the bike” (Brighton, Male, 35-39, int.). Existing UK infrastructure is often perceived as badly maintained, discontinuous or of poor quality.

Survey respondents were also deterred by the size of e-cargo bikes, which would enhance problems related to the infrastructure: “they are too big to be on the road” (Male, 40-44, survey); “it looks difficult to navigate or fit in a bicycle lane” (Female, 40-44, survey), suggesting that they might require enhanced cycling infrastructure.

Trial participants experienced difficulties to manoeuvre on cycle infrastructure due to tight junctions, bollards or narrow alleys, but also because some cycling lanes were too narrow. Additionally, certain paths used by cyclists were not suitable for e-cargo bikes such as off-road routes such as canal towpaths or those involving specific bridges or barriers such as A-frames which are designed to prevent motorbikes access to some routes. Despite these barriers, manoeuvrability difficulties were somewhat overcome as skills develop, as argued by this participant who borrowed a long-john bike: “once you got used to the width of the bike, you realise you can take it quite a few places (Oxford, Female, 40-44, int.)”

Finally, the availability of secure on street parking at destinations is a concern for both survey respondents and trial participants.

4.1.2. Spatial Conflicts and Safety

Many of the survey responses perceive that e-cargo bikes (will) generate conflicts with other active modes, especially pedestrians. Several respondents fear that e-cargo bikes are used on footpaths, which would be especially dangerous for visually impaired individuals and people with disabilities. For instance, the unusual length of the e-cargo bike could be an issue, as these individuals could “collide with the cargo section thinking the bike had passed” (Female, 75-79, survey). A wheelchair user was also concerned that parked shared e-cargo bikes would block the pavements and be even more difficult to bypass than current shared e-bikes or e-scooters (Female, 30-34, survey).

In contrast, trial participants experienced few conflicts with pedestrians and cyclists, most trial participants experienced problems sharing road space with cars. A number mentioned feeling unsafe while riding in traffic, both at the beginning of the trials and after the trials, even if they were fairly confident riders. As a result, some participants made alterations to their trips, such as an Oxford participant who exclusively used cycle paths to avoid interactions with cars, making their trip longer (Oxford, Male, 35-39, int.). However, several trial participants mentioned that the bulkiness of the e-cargo bike made them feel safer among car traffic, such as this Brighton participant: “You feel safer because it’s a larger road presence, it’s a more dominant road presence” (Brighton, Male, 45-49, int.).

Another key perceived barrier emerging from survey responses relates to the safety of passengers, especially children. This is exemplified by this quote: “The thought of having ’little people’ at the front seems dangerous to me given the hazards cyclists face. e.g. poor drivers, potholes, winter weather etc. Kids find it hard to sit still! (Male, 55-59, survey)”.

This concern was shared by many trial participants. Yet, this apprehension is often nuanced, as articulated by this Brighton participant: “I also was a little bit anxious about them falling off and getting run over by a car or, you know, having an accident and stuff. Yeah, there is the danger element. But yeah, I’d always much rather my kids be out in the fresh air” (Brighton, Female, 40-44, int.). Another recurring argument from trial participants was the change in motorists’ behaviours at the sight of children. One Leeds participant, compared riding the e-cargo bike carrying children to the hostile behaviours of drivers when riding a road bike in sports cycling clothing: “when somebody sees that it’s a bloke stood upright with two kids in the front clearly doing a chore rather than a pleasure ride, I think people do give you more space and patience” (Leeds, Male, 40-44, int.). Overall, our data suggests that worries regarding the safety of children as passengers reduce with increased use and experience, which might relate to an increase in skills and confidence.

These arguments around spatial conflicts and safety raise the critical question of where e-cargo bikes fit in space. Although the legal position is that they can be used in the same places as conventional cycles, for some survey respondents, e-cargo bikes should be used exclusively on roads, while others claim that e-cargo bikes belong only on segregated bicycle paths. In addition, some survey respondents believed e-cargo bikes do not fit in either car, pedestrians or shared spaces: “Very dangerous to the rider if used on a road. Very dangerous to pedestrians if used on the footpaths or seaside promenade” (Male, 65-69, survey). This issue was also raised by some trial participants, who expressed feeling uneasy about riding on the road among car traffic, but also sometimes in shared spaces as they, with the electric assistance, are often significantly faster than bicycles and pedestrians.

4.2. Material Barriers

In this section, we discuss first the perceived characteristics of the e-cargo bike and its costs. Then, we outline its cargo capacity to carry passengers and loads.

4.2.1. Vehicle Characteristics

A first impression about e-cargo bikes among survey respondents is that “they seem very bulky and unwieldy” (Female, 25-29, survey). Concerns arise on how to balance and ride on these bigger bikes: “There may be issues with a large load on the front in terms of steering and cornering and securing the load” (Male, 55-59, survey). As for trial participants, they had mixed views regarding the size and the weight of e-cargo bikes

1. Some did not manage to use it and feel confident, whilst many needed some time to adapt and learn: “Once you get used to the balance and get used to the weight of it, it’s fine. It’s like any other new thing that you do, it just takes a little while to get used to it” (Oxford, Male, 45-49, int.). There were also specific instances, particularly on long-john bikes, where it seems more difficult to ride: with heavy cargo, while starting up hill or on narrow infrastructure.

This size also poses an issue for home storage. It is an important barrier mentioned by survey respondents which prevents them from owning one. Secure storage was a pre-requisite for trial participation. Some participants stored bikes in their homes and felt the manual handling getting bikes through narrow corridors or up steps would be impractical in the long term. Having secure storage at ground level would have made it easier to use regularly, according to some participants.

Regarding the electric assistance, some survey respondents perceived that the battery could be a fire hazard, which mirrors issues in the UK around media representation of e-bikes vs illegal 2-wheel mopeds and poor regulation of sales of low-quality e-moped conversion kits. Others were concerned about their environmental impact. Among trial participants, while the electric assist brings benefits, there were still battery-related challenges. One was not allowed to bring the battery in their office building, because building managers perceived e-bikes as a fire risk. Due to the risk of theft, participants were also asked by the project team to remove the battery and take it with them when parting at destinations where theft might be an issue. Battery range was not an issue, but remembering to charge the battery was an extra, although not difficult, task.

The perceived high purchase costs of e-cargo bikes also make people resist early in the adoption process. Some survey respondents think they could get a second-hand car or a small e-car for a lower cost, which would bring them more value. For many trial participants, the price was still a concern that would prevent purchase. This cost is also perceived as higher when considering the high risk of theft. When regular use was possible and owning an e-cargo bike could help reduce or avoid car ownership, then the total cost of ownership was seen as more worthwhile: “financially it should make loads of sense to get [an e-cargo bike] rather than a car because it’s (...) way cheaper to run but they just can’t quite do everything” (Leeds, Female, 40-44, int.). In some instances, such as longer trips, regular users still tended to rely on a car, allowing families to reduce, but not fully replace car ownership. For a few participants, the cargo element was not necessary for their daily tasks and therefore they felt that a conventional e-bike would be enough, especially considering costs.

4.2.2. Cargo Element

Survey respondents showed a general lack of awareness of e-cargo bikes and their purpose. The survey contained images of domestic e-cargo bikes, but some respondents presumed they were for logistics rather than domestic use. The emphasis on the word ‘cargo’ brings a logistics-oriented vision of e-cargo bikes: “Up until now I have never heard of them. They appear to relate to business use rather than personal” (Female, 65-69, survey). Others imagined only the transport of large loads and therefore concluded that an e-cargo bike would not be suitable for them: “Cool but a hire van holds well more stuff” (Male, 45-49, survey). In contrast, our participants became well aware of e-cargo bikes’ domestic application

For survey respondents, shopping was imagined as the main practical use of the e-cargo bike. This functionality was also appreciated by trial participants. Survey respondents who were enthusiastic about e-cargo bikes said that it could help them to not rely on their cars for these trips or support those for which walking while carrying weight is currently difficult. Some saw shopping as the main purpose but still had concerns regarding e-cargo bikes’ carrying capacity and others were afraid they would not have secure parking near the shops. A few respondents highlighted that a normal bike is sufficient for carrying loads, possibly with accessories: “You can get a lot of shopping on a normal bike with panniers” (Male, 65-69, survey). In contrast, many trial participants were positively surprised by the e-cargo bike’s carrying capacity, including big loads such as a kayak. As one participant put it, e-cargo bikes can be seen as “in-between walking and a car in terms of carrying stuff” (Brighton, Female, 70-74, int.).

Some survey respondents also worried that transported loads would get wet in the e-cargo bike, but trial participants felt the rain cover was sufficient for keeping kids and cargo dry. This ease of carrying cargo facilitated multi-purpose trips among participants, for example, facilitating the carrying of a second coat to get changed into on arrival or enabling “a lot of running around, collecting stuff and delivering them” (Brighton, Female, 70-74, int.).

A number of survey respondents perceived carrying passengers as being dangerous: “I’m in favour of these being used to transport goods however I’m not in favour of them being used to transport other people in them. It’s far too dangerous” (Female, 50-54, survey). Few explicitly discussed any benefits of carrying passengers, while these benefits were frequently mentioned by trial participants: “the benefits of it have been transporting the kids. The fact that I can put two kids in there with all their bags from whatever they’re doing, if it’s nursery, taking them to a friend’s house or taking them to a sports club I can get it all in.” (Leeds, Male, 40-44, int.). The e-cargo bike appears ideal for young children who cannot yet cycle (long journeys). Yet, some children would not accept using the e-cargo bike, making it difficult, for some families to rely on that mode. Moreover, a few participants remarked on the negative perception of some other parents who shared concerns about their own children’s behaviours if they were to use one: “I don’t think I’d trust mine [my kids] to do that, to hold on and just sit there” (Leeds, Female, 40-44, int.). Some parents just thought they were strange, and others had quite positive perceptions of cargo bikes.

4.3. Societal Barriers

After discussing spatial and material barriers, this subsection presents the societal barriers to e-cargo bike adoption found in our data. It identifies diverging views on e-cargo bikes as sustainable and active travel before discussing images and cultural perceptions related to their use.

4.3.1. Sustainability

Sustainability appears as a motivation for e-cargo bike adoption for some survey respondents. For instance, one respondent compared e-cargo bikes to e-bikes as being both “very beneficial to the environment” (Male, 75-59, survey). This aligns with the trial participants perspective, as the low environmental impact of e-cargo bikes compared to cars was a motivation for use for some participants. Beyond lowering their mobility-related carbon emissions, some trial participants also saw e-cargo bike use as an educational experience for their children about sustainable alternatives to cars, as this Oxford participant puts it: “knowing that I was making a positive contribution to the environment, that I was displaying positive behaviours to the kids” (Oxford, Male, 30-34, int.) and this Leeds participant: “I suppose finally to be a role model to my daughter so that she can see that it’s possible to live a life without a car” (Leeds, Male, 40-44, int.).

On the other hand, some survey respondents were concerned that e-cargo bikes could replace other active modes, such as walking and cycling, and potentially hinder sustainable mobility. This concern is nuanced in our interview data, as trial participants suggested that the e-cargo bike substitution for active modes depends on the type of trip they were taking in terms of, for example, distance. Lastly, the production and recycling of e-cargo bike batteries stand out as a concern for their negative environmental impact in several survey responses. In the interviews, this aspect is barely mentioned.

4.3.2. Health and Physical Ability

The health benefits of e-cargo bikes seem controversial and are often under-discussed among the survey respondents. While a few survey respondents acknowledged their health advantages, many did not view it as a legitimate form of exercise, particularly when compared to walking and cycling. In contrast, trial participants considered e-cargo cycling as exercise, although at a lower intensity than human-powered cycling. This is especially the case when climbing hills, according to two Brighton participants. A Leeds-based participant also mentioned that e-cargo bike rides were usually longer and more frequent than conventional cycling, thus compensating for the electric assist. Moreover, participants highlighted how e-cargo bikes enabled them to combine utility trips and exercising, such as doing school runs. As one Brighton-based female participant shared; “When you’ve got two young children, it isn’t always possible to do a regular exercise, (…) so being able to just go on like a 15-minute cycle ride (…) is great” (Brighton, Female, 30-34, int.).

A notable finding is that survey respondents perceived their own physical limitations as both a barrier and a motivation for using e-cargo bikes. Some individuals mentioned their age or a disability that could limit their cycling capabilities despite the electric assist, especially in hilly landscapes. Conversely, others considered e-cargo bikes as a promising solution to improve their mobility. One respondent noted: “I am disabled and can’t walk far without sticks but can cycle. I would really appreciate having an e-cargo bike for shopping and helping me get about more without relying on a car” (Female, 65-69, survey). This perspective is supported by our interview data, where some users perceived that e-cargo bikes would be useful to individuals who can no longer cycle due to age or fitness levels. Overall, this suggests that e-cargo bikes could enhance the accessibility of active travel options for those with physical limitations.

4.3.3. Image and Cultural Perceptions

A final subtheme under societal barriers is the concern of image and cultural perceptions of e-cargo bike use. Several survey respondents mentioned that they would not like to be seen on one, because they look ugly and bulky or are associated with particular ‘eco-conscious’ stereotypes: “If I were to own one, I would hope very much that it was stolen if I used it. I mean, come on now, have you seen them? I am not a tree-hugging, lentil-munching vegan, and I would not want to be thought of as one by being seen on such a ridiculous contraption” (Male, 55-59, survey). Some survey responses seem to emphasise a polarisation in British society, between “hippies and eco warrior types” and “some of us living and WORKING

2 in the real world” (Male, 55-59, survey). This polarisation between cyclists and motorists is also mentioned in participants’ interviews which deplore the animosity around Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and the hostile ‘culture war’ rhetoric against cyclists.

These comments contrast with most trial participant experiences, who noted a positive reception within their local communities, with people nodding, smiling and inquiring about the e-cargo bike. Still, some did note that the novelty of e-cargo bikes made them feel out of place, such as this Leeds participant: “The [e-cargo bike] feels very niche, and I felt like I was some sort of (…) weirdo with the [e-cargo] bike, (…) everyone looks at it (…) you could tell like you’re thinking that’s a clown bike” (Leeds, Female, 30-34, int.). Additionally, multiple trial participants mentioned that e-cargo bike use could be a way to ease the existing stigma against cyclists and further normalise cycling practices.

5. Discussion

In this section, we contrast imagined and experienced barriers and seek to highlight how trials can effectively address some of these barriers to e-cargo bike adoption. First, we discuss how the imagined and experienced relative (dis-)advantage of e-cargo bikes are often compared to alternative modes. Then, we point out some barriers that trials do not completely overcome, specifically around the compatibility with the existing infrastructure, and make suggestions for alternative policies. Finally, we highlight how trials, beyond direct adoption, can bring broader awareness about the benefits of this alternative transport mode.

5.1. Relative Material (Dis-)advantages of E-Cargo Bikes

Both trial participants and survey respondents tend to compare the relative (dis-)advantages of e-cargo bikes to alternative transport modes, mainly cars and bicycles. This aligns with Rogers (1995) who identifies relative advantage as a key element influencing adoption and defines it as the evaluation of the benefits brought by an innovation compared to what it replaces. In our study, it directly relates to individuals’ willingness to change their mobility habits, which largely rely on cars in the British context.

In our findings, e-cargo bikes are recognised by both trial participants and some survey respondents for overcoming some material limitations of conventional bicycles, for instance, in terms of carrying cargo or passengers. However, they are also perceived as lacking certain advantages of cars, such as weather protection or the safety of children in traffic. Yet, this does not seem to be a barrier for participants, and parents seem to be dominant among owners of e-cargo bikes, aligning with existing cargo bike studies (e.g., Marincek et al., 2024; Riggs, 2016). In addition, the ability to travel more sustainably and actively by avoiding car use is perceived as a relative advantage of e-cargo bikes. Some survey respondents did express concerns about the environmental impact of electrification, especially regarding battery production and disposal, as well as the shift away from other active modes. This criticism resonates with academic work on the environmental implications of e-micromobility modes (Şengül & Mostofi, 2021).

Due to the electric-assistance, the perceptions of e-cargo bikes’ contribution to physical activity differed across trial participants and survey respondents. Indeed, some survey respondents point out how conventional bicycles require more physical activity than e-cargo bikes. However, while some trial participants also point out that the intensity is lower, most recognise that it allows for a more frequent use of the bike, increasing overall activity. This finding concurs with existing e-bike studies that found that e-bike users tend to cycle longer distances than regular bicycle users (Fishman & Cherry, 2016; Fyhri et al., 2017), resulting in increased physical activity (Gojanovic et al., 2011). Similarly, Hall et al. (2019) found that experienced mountain bikers did not perceive riding an e-mountain bike as physically demanding, while most did reach a lower but vigorous level of exertion while riding it. This perception of ease, while still bringing health benefits, can reduce adoption barriers, incentivising those who could be discouraged by the effort of active mobility.

Finally, another important comparison with other modes is with regards to cost and perceived financial value. Our results show how the initial investment for purchasing an e-cargo bike can deter potential users, especially when compared to the cost of a regular bicycle. Yet, people often evaluate this cost compared to the cost of cars and the value that ownership brings them. This is also pointed out by Thomas (2022) where participants compared with the running costs of owning a car, such as parking fees and gas. For people willing to change, trials can, through experience, reduce uncertainties associated with e-cargo bike adoption while the commitment is still reversible (e.g., car has not been sold) and without financial risk (Stromberg et al., 2016). In another dataset, most of our participants perceived e-cargo bikes as better value for money after participating in the trial (ANONYMISED). For others and many survey respondents, without an identified need for it and desire to change, the cost is seen as prohibitive, and trials would not help to overcome this barrier.

5.2. Compatibility with Existing Infrastructure

Some barriers to e-cargo bike adoption are not fully overcome by trials and would need broader policies or infrastructural changes to be tackled. A key barrier arising in our study relates to e-cargo bikes’ compatibility with existing road infrastructure. Many trial participants and survey respondents perceive infrastructure as built for cars, making it unsafe for cyclists, as has been highlighted in previous research (Bourne et al., 2020). Additionally, trial participants pointed out that when cycling infrastructures exist, they are not always adapted to e-cargo bikes and some participants therefore preferred to ride on the main road.

Further adaptation to infrastructure and spatial organisation would enable the adoption of e-cargo bikes but also benefit other active modes. In the Netherlands, a knowledge platform focused on cycling recently proposed guidelines reconsidering the default width of cycle lanes. Where cycle lanes are too narrow, the organisation suggests encouraging cargo bikes to use roads by reducing speed limits to 30km/h (CROW Fietsberaad, 2022). Some participants in our trials stated that with an e-cargo bike they occupy more space on the road than with a conventional bike and therefore feel safer. Another study with e-bike users in the UK highlighted the ability to keep up with traffic speed as a benefit of the electric assistance (Jones et al., 2016).

A recurring topic in survey responses was the fear of crashes and concerns for the safety of passengers, particularly children. This resonates with cycling research that identifies perceived safety as a key barrier to (e-cargo) cycling (Marincek et al., 2024). Such concerns are especially exacerbated by the presence of motorised traffic, a finding supported by our study. This suggests that safety concerns are not inherently linked to e-cargo bikes and should be viewed within the broader context of car dominance. Our findings show that embodied user experiences can help alleviate these barriers, suggesting that trialability can foster confidence. Consistent with existing cargo bike research (Thomas, 2022), trial participants reported that the noticeable presence of e-cargo bikes on the road – compared to regular bicycles – made them feel safer.

Storage and parking also emerged as a significant barrier perceived by both groups, particularly due to the size, weight and value of e-cargo bikes. Considering this, cities are looking for solutions such as broadened bicycle parking spaces or cargo bike-specific racks (Parking.Brussels, 2021). These adaptations seem essential to support e-cargo bike adoption, but also facilitate the use of adapted cycles, such as tricycles or handcycles (National Transport Authority, 2023).

5.3. Societal Awareness and Wider Impacts

Beyond individual use and adoption, our study revealed the wider impacts of trial programs in terms of acceptance and awareness of e-cargo bikes as a mobility option.

Our investigation shows a lack of familiarity with e-cargo bikes among survey respondents; notably, 49 respondents explicitly stated they had never even heard of them. This result aligns with the relative limited presence of e-cargo bikes in the UK compared to other European countries such as Germany or the Netherlands. For many, the word e-cargo bike directly echoes a bulky and logistic-oriented vision. This perception is reflected by common definitions of cargo, such as the Cambridge dictionary definition: the goods carried by a ship, aircraft, or other large vehicle. As such, many individuals have not imagined e-cargo bikes as something they could ever use for personal transport. This logistic-centred vision is also reflected in existing cargo bike literature that has considered domestic use to a lesser extent (Narayanan & Antoniou, 2022).

In contrast, trial participants were already familiar with e-cargo bikes, as they had agreed to participate in free trial loans, though most had no previous experience in riding them. Beyond the participants’ own experience, such trials can have ripple effects and help normalise their domestic use. Participants’ experiences are observable to others and can influence broader public perceptions, and possibly adoption (Strömberg et al., 2016).

Lastly, image and perception barriers stood out strongly in the survey responses. These barriers may contribute to e-cargo bike resistance, as individuals are influenced by what their social circles approve of (Joachim et al., 2018). This barrier reflects Horton (2007) and Glachant & Behrendt (2024) on issues of identity, such as the stigma surrounding cycling and scootering practices, respectively in the UK and the Netherlands. This concern seems especially strong in the UK, where cyclists are often framed as risk-takers, assertive and deviant from the dominant practice of car driving, which is considered the norm (Aldred, 2013). From the perspective of survey respondents, e-cargo cycling can be viewed as a way to demonstrate environmental values – resonating with Boterman’s (2020) research on cargo bikes in the Netherlands. Trial participants’ experiences, on the other hand, reflect more positive perceptions, particularly regarding interactions with local communities. This suggests a potential pathway to shift cultural perceptions of cycling in the UK, which is crucial given that these perceptions act as barriers to cycling adoption (Horton & Jones, 2015).

6. Conclusion

This study adopts a mixed-method approach to compare the imagined barriers of individuals who have not used an e-cargo bike to the experienced barriers of those who participated in long-term e-cargo bike trial loans in the suburbs of Brighton, Leeds and Oxford. Our findings are structured around three sets of barriers: spatial, material and societal.

This paper’s contributions are twofold. First, it contributes to the emerging e-cargo bike literature with a study on domestic use that focuses on perceptions and how they relate to adoption. These public perceptions can greatly influence the adoption of new innovations and practices, particularly when an innovation is trying to move beyond the early adopter phase (Rogers, 1995) or for the niche to stabilise and develop (Markard et al., 2012; Smith & Raven, 2012), in innovation studies terms. Second, it advances scholarship on trial programs as interventions to encourage the adoption of sustainable mobility modes, which is crucial given the pressing need to decarbonise urban mobility.

Material barriers are often addressed through trial experiences, as participants get more comfortable and familiar with e-cargo bikes. These trials also allow participants to evaluate, without taking financial risks, the relative advantages of e-cargo bikes, such as usability, sustainability and physical activity, compared to alternatives. Societal barriers, mostly related to the general lack of familiarity with e-cargo bikes and the stigmatisation of cyclists in the UK, were generally overcome for participants. Trials could play a role in mitigating these barriers for non-users of e-cargo bikes through the observability of positive participant experiences. In contrast, spatial barriers, such as poor cycling infrastructure and the prioritisation of motor traffic, persist and cannot be overcome through trials alone.

By identifying the significant gaps between imagined and experienced perceptions, it provides an opportunity for manufacturers, businesses and policymakers to challenge misconceptions, myths and misinformation. Building on our findings, we propose the following policy recommendations. As evidenced by the 10 households who decided to purchase e-cargo bikes within a year after the trial, trials are a promising strategy to disrupt long-term mobility habits and promote e-cargo bike adoption. Policymakers may then consider experimenting with trials as ways to deliberately support sustainable transport technology niches for fostering mobility transitions. However, cycling infrastructure remains an issue despite the trials, and improvements are needed alongside policy to limit car use. Attention should be given to rural areas (A roads) where (e-cargo) cyclists share the road with fast-driving cars. Moreover, price stood out as a significant barrier to adoption among non-users. Policies could tackle this barrier through subsidies, such as those directed to electric car purchase (Behrendt, 2018), and possibly cycle to work schemes

Our research has limitations that might lead to further research. First, it was conducted in the car-centric British context, which may affect the perception of e-cargo cycling and limit the transferability of our findings. It would be relevant to examine other contexts with a strong cycling culture, such as the Netherlands. Second, our methodology and the selection of our datasets may bring some limits with regards to representativity. As such, our results do not show which are the most pressing barriers to overcome, but rather identify barriers that are imagined by some individuals. Future research could evaluate the weight of these barriers by running another representative survey questioning, with close-ended questions, the importance of each identified imagined barrier.

Funding

This work is supported by UK Research and Innovation under Grant [UKRI EP/S030700/1] and is part of the CREDS research community.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the interviewees and survey respondents for their input. We are also grateful to the members of the ELEVATE project who all contributed to the broader project design, data collection and/or analysis.

| 1 |

It should be noted that not all participants tried the same bike: long-tail and long-john bikes were available, of various brands. The type of bike received depended on the city and to some extent on participants’ need to carry children, but not based on an individual morphology. All this can influence participants’ experience regarding size, weight and stability. Bikes un-ladened weight varies from 30kg (Benno Boost longtail) to approx. 60kg (Raleigh stride long-john). |

| 2 |

Emphasis in original. |

References

- Abou-Zeid, M., & Ben-Akiva, M. (2012). Travel mode switching: Comparison of findings from two public transportation experiments. Transport Policy, 24, 48–59. [CrossRef]

- Aldred, R. (2013). Incompetent or Too Competent? Negotiating Everyday Cycling Identities in a Motor Dominated Society. Mobilities , 8(2), 252–271. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, F. (2018). Why cycling matters for electric mobility: towards diverse, active and sustainable e-mobilities. Mobilities, 13(1), 64–80. [CrossRef]

- Bjørnarå, H. B., Berntsen, S., te Velde, S. J., Fyhri, A., Deforche, B., Andersen, L. B., & Bere, E. (2019). From cars to bikes – The effect of an intervention providing access to different bike types: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 14(7), e0219304. [CrossRef]

- Börjesson Rivera, M., & Henriksson, G. (2014). Cargo Bike Pool : A way to facilitate a car-free life? Resilience - the New Research Frontier. Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Development Research Conference. , 273–280. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-172043.

- Boterman, W. R. (2020). Carrying class and gender: Cargo bikes as symbolic markers of egalitarian gender roles of urban middle classes in Dutch inner cities. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(2), 245–264. [CrossRef]

- Bourne, J. E., Cooper, A. R., Kelly, P., Kinnear, F. J., England, C., Leary, S., & Page, A. (2020). The impact of e-cycling on travel behaviour: A scoping review. Journal of Transport & Health, 19, 100910. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S., Behrendt, F., Raffo, D., Beaumont, C., & Kiefer, C. (2017). Electrically-assisted bikes: Potential impacts on travel behaviour. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 103, 327–342. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S. , & Sloman, L. (2019). Potential for e-cargo bikes to reduce congestion and pollution from vans in cities.

- Cairns, S. , Sloman, L., Newson, C., Anable, J., Kirkbride, A., & Goodwin, P. (2008). Smarter choices: Assessing the potential to achieve traffic reduction using “Soft measures.” Transport Reviews, 28(5), 593–618. [CrossRef]

- Cass, N., Azzouz, L., & Marks, N. (2024). Elevate Project: Participant Interview Data, 2023-2024. UK Data Service. [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Committee. (2023). Progress in reducing emissions. 2023 Report to Parliament.

- CROW Fietsberaad. (2022). Geactualiseerde aanvevelingen voor de breedte van fietspaden 2022.

- Dill, J., & Rose, G. (2012). Electric bikes and transportation policy. Transportation Research Record, 2314, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Félix, R., Moura, F., & Clifton, K. J. (2019). Maturing urban cycling: Comparing barriers and motivators to bicycle of cyclists and non-cyclists in Lisbon, Portugal. Journal of Transport & Health, 15, 100628. [CrossRef]

- Filipe Teixeira, J., Diogo, V., Bernát, A., Lukasiewicz, A., Vaiciukynaite, E., & Stefania Sanna, V. (2023). Barriers to bike and e-scooter sharing usage: An analysis of non-users from five European capital cities. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 13, 101045. [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E., & Cherry, C. (2016). E-bikes in the Mainstream: Reviewing a Decade of Research. Transport Reviews, 36(1), 72–91. [CrossRef]

- Fyhri, A., Heinen, E., Fearnley, N., & Sundfør, H. B. (2017). A push to cycling—exploring the e-bike’s role in overcoming barriers to bicycle use with a survey and an intervention study. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 11(9), 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Garidis, S. (2023). Bicycle Association UK e-bike market results, e-bike summit 5 September 2023. In Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

- Glachant, C., & Behrendt, F. (2024). Negotiating the bicycle path: A study of moped user stereotypes and behaviours in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 107, 301–320. [CrossRef]

- Gojanovic, B., Welker, J., Iglesias, K., Daucourt, C., & Gremion, G. (2011). Electric bicycles as a new active transportation modality to promote health. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(11), 2204–2210. [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. (2024, December 10). EAPC standards and legal requirements. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/electrically-assisted-pedal-cycles-eapcs/electrically-assisted-pedal-cycles-eapcs-in-great-britain-information-sheet.

- Grudgings, N., Hagen-Zanker, A., Hughes, S., Gatersleben, B., Woodall, M., & Bryans, W. (2018). Why don’t more women cycle? An analysis of female and male commuter cycling mode-share in England and Wales. Journal of Transport and Health, 10, 272–283. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C., Hoj, T. H., Julian, C., Wright, G., Chaney, R. A., Crookston, B., & West, J. (2019). Pedal-Assist Mountain Bikes: A Pilot Study Comparison of the Exercise Response, Perceptions, and Beliefs of Experienced Mountain Bikers. JMIR Formative Research, 3(3), e13643. [CrossRef]

- Harms, L., Bertolini, L., & te Brömmelstroet, M. (2014). Spatial and social variations in cycling patterns in a mature cycling country exploring differences and trends. Journal of Transport & Health, 1(4), 232–242. [CrossRef]

- Hess, A. K., & Schubert, I. (2019). Functional perceptions, barriers, and demographics concerning e-cargo bike sharing in Switzerland. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 71, 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Horton, D. (2007). Fear of Cycling. In P. Rosen, P. Cox, & D. Horton (Eds.), Cycling and Society (pp. 133–152). Ashgate.

- Horton, D. , & Jones, T. (2015). Rhetoric and Reality: Understanding the English Cycling Situation. In P. Cox (Ed.), Cycling Cultures (pp. 63–77). University of Chester Press.

- Jaramillo, P. , Kahn Ribeiro, S., Newman, P., Dhar, S., Diemuodeke, O. E., Kajino, T., Lee, D. S., Nugroho, S. B., Ou, X., Hammer Stromman, A., & Whitehead, J. (2022). Transport. In Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change. (pp. 1049–1160). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Joachim, V., Spieth, P., & Heidenreich, S. (2018). Active innovation resistance: An empirical study on functional and psychological barriers to innovation adoption in different contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 71, 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Jones, T., Harms, L., & Heinen, E. (2016). Motives, perceptions and experiences of electric bicycle owners and implications for health, wellbeing and mobility. Journal of Transport Geography, 53, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R., Schot, J., & Hoogma, R. (1998). Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 10(2), 175–198. [CrossRef]

- Lahon, M., & Engelen, M. (2024). Quel Potentiel du Vélo Cargo Aupres des Familles en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale ? https://bx1.be/categories/news/apres-trois-ans-de-test-bruxelles-mobilite-tire-un-bilan-positif-du-projet-cairgo-bike/.

- Marincek, D., Rérat, P., & Lurkin, V. (2024). Cargo bikes for personal transport: A user segmentation based on motivations for use. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955–967. [CrossRef]

- Melia, S., & Bartle, C. (2021). Who uses e-bikes in the UK and why? International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. [CrossRef]

- Moser, C., Blumer, Y., & Hille, S. L. (2018). E-bike trials’ potential to promote sustained changes in car owners mobility habits. Environmental Research Letters, 13(4), 044025. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S., & Antoniou, C. (2022). Electric cargo cycles - A comprehensive review. Transport Policy, 116, 278–303. [CrossRef]

- National Transport Authority. (2023). Cycle Design Manual. https://www.nationaltransport.ie/publications/cycle-design-manual/.

- O’Cathain, A., & Thomas, K. J. (2004). “Any other comments?” Open questions on questionnaires - A bane or a bonus to research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 4(1), 1–7.

- Pan, M., & Ryan, A. (2024). Promoting Sustainable Transportation Modes: A Systematic Review of Behavior-Change Strategies. Transportation Research Record.

- Parking.Brussels. (2021). Stratégie de stationnement - vélos cargo en Région Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Philips, I., Azzouz, L., Séjournet, A. de, Anable, J., Behrendt, F., Cairns, S., Cass, N., Darking, M., Glachant, C., Heinen, E., Marks, N., Nelson, T., & Brand, C. (2024). Domestic Use of E-Cargo Bikes and Other E-Micromobility: Protocol for a Multi-Centre, Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024, Vol. 21, Page 1690, 21(12), 1690. [CrossRef]

- Philips, I., Brown, L., & Cass, N. (2024). E-bike use and ownership in the Lake District National-Park UK. Journal of Transport Geography, 115, 103813. [CrossRef]

- Philips, I., Cairns, S., de Séjournet, A., Anable, J., Azzouz, L., Behrendt, F., Brand, C., Cass, N., Darking, M., Glachant, C., Heinen, E., Marks, N., & Nelson, T. (2025). E-Cargo Bikes as a Personal Transport Mode in the UK: Insights from National Surveys and Suburban Trials. Prepring.Org. [CrossRef]

- Popovich, N., Gordon, E., Shao, Z., Xing, Y., Wang, Y., & Handy, S. (2014). Experiences of electric bicycle users in the sacramento, california area. Travel Behaviour and Society, 1(2), 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Riggs, W. (2016). Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, L., Soliz, A., Manaugh, K., Kestens, Y., & El-Geneidy, A. (2024). Opinions matter: Contrasting perceptions of major public transit projects in Montréal, Canada. Transport Policy, 157, 34–45. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (3rd ed.). Free Press.

- Sengers, F., Wieczorek, A. J., & Raven, R. (2019). Experimenting for sustainability transitions: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Şengül, B., & Mostofi, H. (2021). Impacts of e-micromobility on the sustainability of urban transportation—a systematic review. Applied Sciences, 11(13), 5851. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., & Raven, R. (2012). What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy, 41(6), 1025–1036. [CrossRef]

- Speak, A., Taratula-Lyons, M., Clayton, W., Shergold, I., Speak, A., Taratula-Lyons, M., Clayton, W., & Shergold, I. (2023). Scooter Stories: User and Non-User Experiences of a Shared E-Scooter Trial. Active Travel Studies, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, H., Rexfelt, O., Karlsson, I. C. M. A., & Sochor, J. (2016). Trying on change – Trialability as a change moderator for sustainable travel behaviour. Travel Behaviour and Society, 4, 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. (2009). Promoting public transport as a subscription service: Effects of a free month travel card. Transport Policy, 16(6), 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. (2022). Electric bicycles and cargo bikes—Tools for parents to keep on biking in auto-centric communities? Findings from a US metropolitan area. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 16(7), 637–646. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).