Safety Components and GRAS Process

The safety of all ingredients used in foods is paramount. The legal definition of ingredient safety in the United States is codified in the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 170.3(i) and 21 CFR 570.3(i)). These regulations stipulate that, based on the preponderance of scientific evidence, there is a reasonable certainty of no harm under the conditions of use. Thus, the final safety of a food ingredient is mediated through fundamental concepts of harm, viz., benefits and risks.

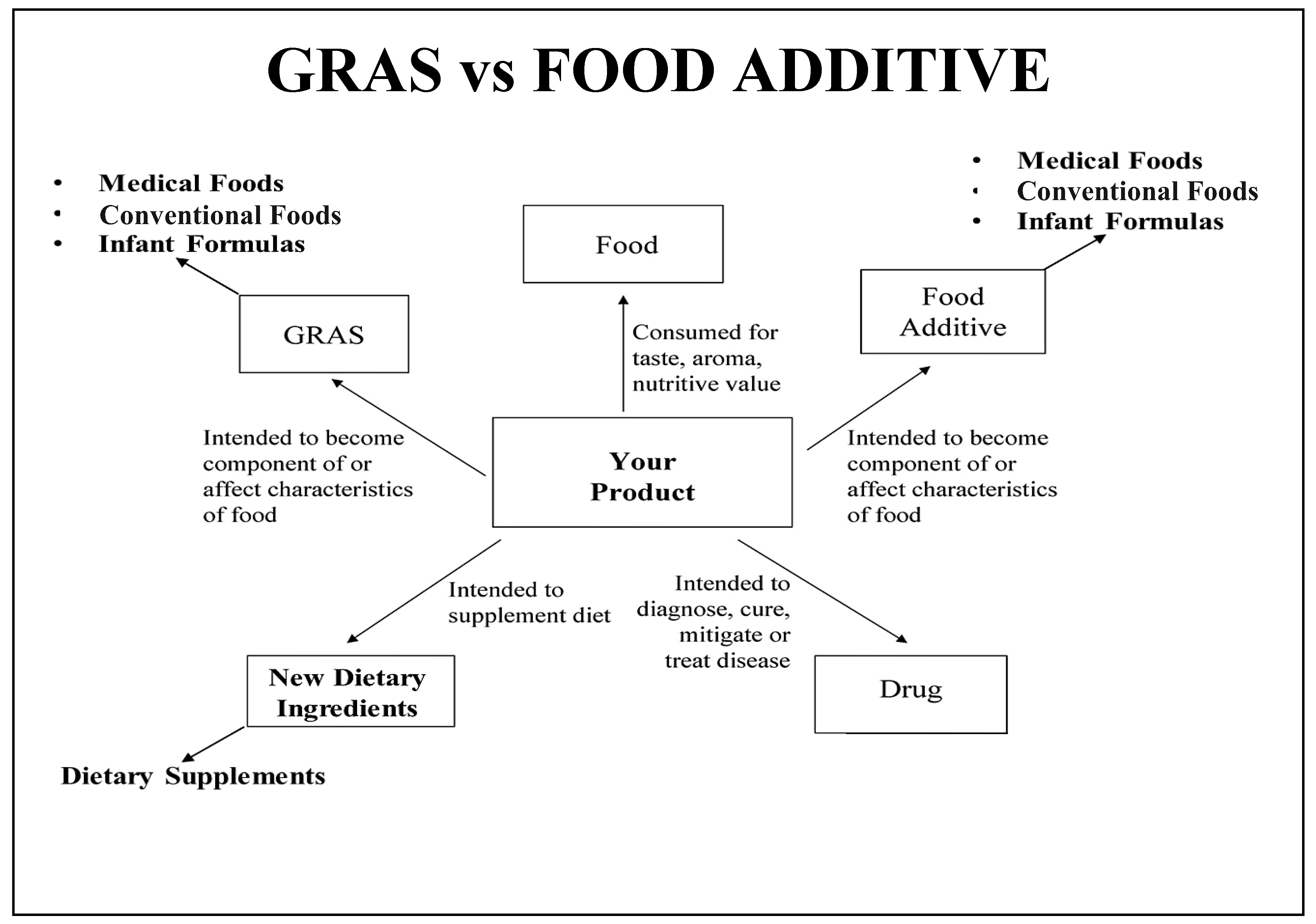

All ingredients used in the design and formulation of infant formulas intended to be marketed in the United States must adhere to the safety criteria for food additives or GRAS (

Figure 1). The requirements for food additive petitions are stipulated in a 2009 FDA guidance document [

5]. The final rule for GRAS was published in 2016 [

6]. This action reflected, in part, the increased incorporation of novel ingredients in the food supply since the introduction of the Food Additives Amendment to the Food, Drug & Cosmetic(FD&C) Act in 1958.

Food additives introduced to the US market after 1958, as stipulated by Congress, must undergo pre-market approval. Yet, the FD&C amendment noted that the agency had not reviewed some food ingredients. In 1969, the US government initiated the evaluation of GRAS substances, a process that commenced in 1972. The GRAS notification process began in 1997.

While many argue that the GRAS affirmation process is biased by sponsor involvement and by the panel of scientific experts, it is essential to acknowledge a conflict of interest (COI) declaration by prospective GRAS panel members and the absence of sponsor involvement (other than providing pertinent data) in the GRAS panel review. The COI issue was discussed in a 2009 IOM report [

7] and addressed in the 2016 final ruling for GRAS [

6]. This COI notice is intended to ensure that the GRAS panel members are independent and are devoid of any relationship with the GRAS sponsor and related companies associated with the food ingredient under review.

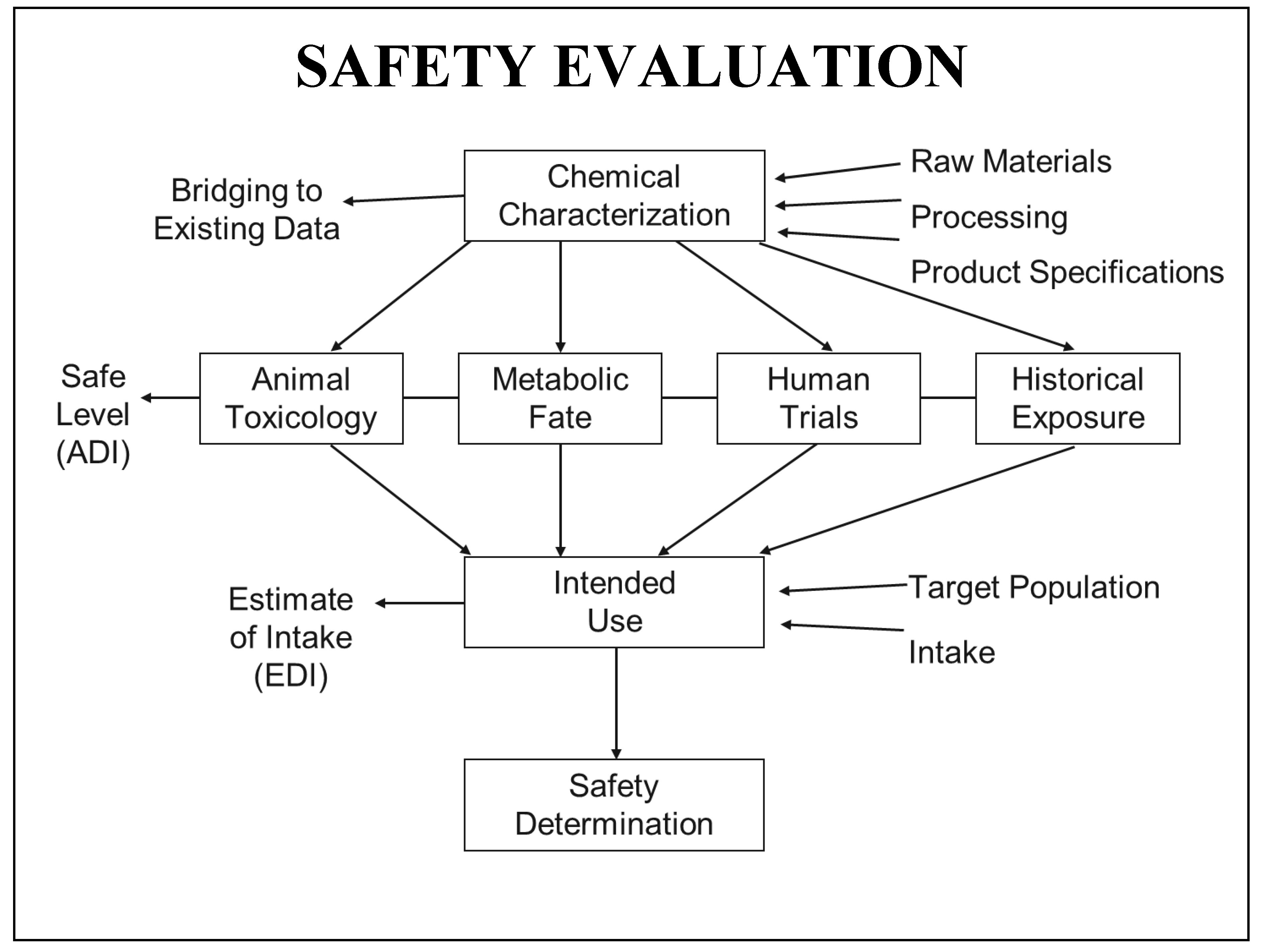

The criteria for assessing ingredient safety and toxicology are identical for food additives and GRAS ingredients (

Figure 2). The only differences are the time for review and potential approval, as well as the data required for the intended technical effect. For a food additive, the FDA mandates a 120-day review period. Importantly, the agency must act on a petition within 180 days. Similarly, the FDA must respond to a GRAS notification within 180 days. On the other hand, with a GRAS affirmation dossier approved by the panel of experts, the reviewed food ingredient can be immediately introduced into commercial distribution. Regarding ingredients intended for infant formula, critical clinical data would have been included in the GRAS dossier. While a food additive petition and GRAS dossier require the same basic information, some investigators suggest that the food additive petition requires more safety information.

Interestingly, a food additive petition requires premarket approval by the FDA, whereas a GRAS affirmation process does not require FDA notification. This latter point is an issue for some organizations that contend the GRAS affirmation is a GRAS loophole that could compromise food safety [

8].

Within the chemical characterization step, physicochemical properties and technical functional effects are assessed using current analytical technologies. This step considers potential processing impurities, environmental contaminants, biological toxins, and heavy metals, such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic. Information available in the public scientific literature and regulatory agencies is leveraged in this process. Traditional toxicological evaluations typically include acute and chronic studies involving appropriate animal models plus mutagenicity and carcinogenicity using

in vitro,

in vivo assays and rodent bioassays. These evaluations are presented in the updated FDA Red Book (FDA) [

9] and outlined in the scientific International Council for Harmonization (ICH) guidelines [

10].

The ICH guidelines consider impurities, dose selection for carcinogenicity studies, genotoxicity, toxicokinetics, reproductive toxicity, and immunotoxicity. Many companies follow OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) guidelines for toxicological assessments [

11]. These types of toxicological studies in practice lead to the establishment of a NOAEL (no-observed-adverse-effect level). A typical margin of safety (MoS) is then applied to NOAEL to establish a dose considered safe for humans. A typical MoS value is 100, thereby providing a dose of a food ingredient that does not exceed health thresholds (e.g., non-genotoxic, non-carcinogenic). This dose, NOAEL/100, is often expressed as mg/kg body weight per day (mg/kg bw/day) and is known as the Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI).

Preclinical safety assessments are considered before designing appropriate clinical studies. Those clinical studies followed traditional protocols approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). For example, the recent inclusion of oligosaccharides, such as 2’-fuctosyllactose, lacto-N-neotetraose, fructooligosaccharides, and galactooligosaccharides. The safety of these substances was reviewed by GRAS panel members whose training and experience qualified them as experts. The GRAS documentation for these substances is available at the FDA GRAS Inventory website [

12].

During the past several decades, many new ingredients have been introduced into infant formulas marketed in the United States. While some infant formula components are not listed in the Infant Formula Act, including lactoferrin, polyunsaturated fatty acids, probiotics, and oligosaccharides, they are now commonly found in infant formulas in an attempt to mimic the health benefits of human milk. The US regulations have not established minimum or maximum values for these components.

Impact of Environmental Chemicals on Infant Development

Chemicals in the environment can have lasting and detrimental effects on infants and young children, as these individuals are still developing and are therefore more susceptible to known and unknown pathways of toxicity than adults. This susceptibility can lead to alterations in cognitive performance, delays in puberty and behavioral development, and adverse effects on the immune system. Major factors accounting for this early life-stage susceptibility include: allometric scaling (higher food (formula) to body weight consumption ratio); immature metabolic capacity for chemical detoxification and excretion (allows greater distribution of chemicals to different organ systems); and immaturity of the blood-brain barrier (allows chemical access to the developing brain).

Environmental contaminants of particular concern for infantile and early life exposure include heavy metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium [

13,

14,

15], plasticizers such as phthalates [

16], ‘forever chemicals’ like PFAS [

17], microplastics and nanoplastics [

18], endocrine disrupting chemicals such as PCBs, dioxins, some pesticides, and flame retardants [

19,

20], and some food additives and dyes classified either as direct (e.g., colorants, flavoring agents, preservatives) or indirect (based on processing equipment that includes adhesive, dyes and coatings, and packaging) [

21]. Given that infants not fed on human breast milk rely primarily on formula as their primary nutritional source, they may experience a greater risk from these environmental contaminants.

Consumer Reports recently tested 41 types of powdered formula for several toxic chemicals, including heavy metals, and published their findings on March 18, 2025 [

22]. Mercury and cadmium were not detected or were well below levels of concern in the infant formulas tested; however, concern remained over the detectable levels of arsenic and lead. The risks and effects of these contaminants through formula depend on the levels and duration of exposure, as well as whether the infant may have already been exposed prenatally through the intrauterine environment and during a vulnerable stage of development. Here, we review evidence as to: (1) which environmental contaminants (focusing on heavy metals as examples) may be most beneficial to test for; (2) summarize what existing recommendations and guidelines have been established internationally for environmental contaminants; and (3) briefly identify research gaps in scientific understanding of environmental contaminants in infant formula.

International Guidelines

In the United States, there are no established maximum allowable levels set for any environmental contaminants in infant formula. While the FDA’s Closer to Zero Initiative, launched in 2021, aims to develop action levels for heavy metals in juices and foods intended for infants and children, particularly in food where some contamination is unavoidable, infant formula has not been included. Furthermore, no clear consequences or enforceable regulations have been established yet for any contaminants that exceed the hypothetical action levels [

23]. Although many formula manufacturers in the United States may already conduct independent testing for environmental pollutants, such as heavy metals, it is essential to standardize testing practices across the industry as well as an established list of which environmental contaminants are most relevant to assess. Evaluation should include both individual ingredients and finished products [

24]. Additionally, increased transparency from the US FDA regarding the frequency of testing and the most recent contaminant levels is critical for rebuilding consumer trust in the safety of US formulas.

For several specific environmental contaminants, maximum levels have already been established for infant formula in the European Union, Canada, and Australia/New Zealand; however, even among our international counterparts, there is variation on which environmental contaminants to monitor (

Table 1). The European Union (EU) maintains the most extensive maximum allowable limits for infant formula contaminants, including aflatoxins, lead, cadmium, arsenic, tin since it is an anti-rust barrier between the steel and the epoxy lining of canned infant formulas, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and melamine, with updates implemented by the European Commission [

25]. By comparison, Australia has proposed maximum limits for only four infant formula contaminants (lead, vinyl chloride, aluminum, and acrylonitrile) in its own 2023 updated review on the regulation of infant formula products revised under Proposal P1028 – Infant Formula [

26]. For Canada, maximum limits are proposed for only lead (0.01 ppm) in infant formula [

27]. Codex Alimentarius (Codex) an international food standards body established by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO), of which the US is a member, provides another reference with recently updated contaminant specifications in infant formulas (for lead and melamine) [

28]. Regardless of the initial selection of regulated environmental contaminants in infant formula, a systematic review cycle should be conducted at least every five years with an established expert panel, allowing for an expanding list as research identifies additional harmful substances.

While there has been research conducted in mouse models as well as in cross-sectional population-based studies, the health effects of mild-moderate heavy metal exposure in infants are relatively understudied. Toxic metals do not exist in isolation and can often disrupt the homeostasis of essential elements [

29]. Thus, additional studies are needed to examine whether exposure to a mixture of contaminants could have synergistic effects on one another and potentially interact with some of the newly added bioactive ingredients. Understanding these interactions may help guide the establishment of maximum allowable levels that have not yet been determined and established.

As mentioned previously, while human milk is the ideal source of nutrition with multiple immunological benefits, infants can also be exposed to environmental contaminants, specifically heavy metals, through the maternal environment and diet [

30]; consequently, effective reduction of ecological contaminants for all infants, regardless of diet, requires not only regular monitoring systems, but also a collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure that environmental regulations are in place to safeguard our food supply from industrial heavy metal pollution through soil, air and water pathways.

New Approach Methods (NAMs) for Basic Research and Discovery in Risk Science

Toxicology testing plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety of regulated products and is typically conducted in animal studies. NAMs are being developed for toxicity testing to enhance the capacity to quickly and accurately predict the potential risk from chemical, physical, or biological agents in the animal-free zone, leveraging the latest advances in science and technology, such as organs-on-chip or mathematical modeling.

The EPA defines a NAM as “any technology, methodology, approach, or combination thereof that can be used to provide information on chemical hazard and risk assessment that avoids the use of intact animals” [

31]. NAMs are part of the FDA’s Predictive Toxicology Roadmap to support replacement, reduction, and refinement (3Rs) of animal studies” [

32].

A shared vision for the future of toxicity testing in the 21st century was formalized in a federal collaboration among the NIH, EPA, and FDA [

33]. The overarching goal is to screen large numbers of chemicals for the potential to disrupt cellular processes underlying adverse health effects using high-throughput robotics and computer modeling. Various modalities are part and parcel to this effort with the integration of information and knowledge from NAMs vital for translation to improved healthcare strategies, including high-throughput screening (HTS) for ascertaining bioactivity profiles of chemical-biomolecular target interactions assayed across an in-vitro concentration range; high-throughput kinetics (HTK) as an in-silico tool for in-vitro to in-vivo extrapolation of dosimetry across species and life-stage; structure-activity relationships (SAR) to as a computational tool to infer / predict bioactivity potential for untested chemicals having structural similarity to tested chemicals; microphysiological systems (MPS) to directly test chemical effects using human cell-based organotypic culture models; adverse outcome pathways (AOP) for evidence-based elucidation of toxicity pathways from molecular initiating event to adverse outcome of regulatory value in risk science; and agent-based modeling (ABM) for reconstructing cellular dynamics in-silico using computer models harboring self-organizing intelligence based on known biology [

34].

Safety by Design

Throughout this manuscript, numerous aspects of the safety of infant formula ingredients and the finished products have been presented. While potential environmental contaminants are briefly discussed in this manuscript, the extensive list of classic mycotoxins and endotoxins, along with their respective maximum levels in infant formula, has not been established in the United States or by the Codex. However, GRAS dossiers for infant formula ingredients typically address this issue by leveraging upper limits, tolerable intake levels, and margins of exposure, using WHO guidelines for a range of pesticides. The EU infant formula pesticide limits are typically not detectable, which is set at a level of less than 10 ppb [

35]. In addition, the European Union has established maximum residue levels for mycotoxins, heavy metals, and pesticides [

25]. A typical surrogate indicator of mycotoxin exposure is aflatoxin B1 at 15 ppb; however, neither Codex, the European Union, nor the United States has codified an action level of mycotoxins in infant formula

per se.

Potential microbial contamination standards have been reactionary in the United States. Regardless, the FDA has established strict microbial limits for infant formula. Of primary concern for the agency are Salmonella (absent in 25g), Cronobacter (absent in 10g), coliforms (maximum not specified), Shiga-toxin producing

E. coli. (maximum limit not established) and

Bacillus cereus. Staphylococcus aureus (not detected in 1g) and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (not detected in 1 g) are typically included in the product specifications. The limit for

B. cereus is not explicitly stated in US regulations; however, the FDA requires that

B. cereus must not be detected in infant formula. This organism continues to receive attention due to its production of an emetic toxin and up to five different enterotoxins, the assessment of which is not specified for infant formula ingredients or the finished product [

36].

Enterobacter sakazakii, now known as

Cronobacter sakazakii, an environmental contaminant, is a serious source of infections in infants. This organism forms a biofilm, which can become problematic on the surfaces of food production equipment and facility structures. These biofilms are difficult to eliminate due to their resistance to typical cleaning and sterilization procedures [

37].

The FDA has not established maximum levels for yeast and molds and has yet to address viruses that may pose a public health risk. Fortunately, thermal processing conditions for producing powder and liquid forms of infant formula can inactivate most viruses and other microbes. Regardless of these microbial hurdles, the FDA’s safety standards for infant formula ingredients and quality control procedures are intended to assure the safety and quality of the finished product [

38].

Conclusion

The safety, regulation, and availability of infant formula are vital public health concerns that demand coordinated oversight, scientific rigor, and more well-defined guidelines (

Table 2). The 2022 formula shortage exposed critical vulnerabilities in the US regulatory framework, prompting initiatives like Operation Stork Speed to reevaluate and modernize policies. This manuscript underscores the need for streamlined FDA approval processes, enhanced transparency in ingredient safety through GRAS and food additive pathways, and stronger protections and guidelines on levels of microbials as well as environmental contaminants, such as heavy metals. We have highlighted advances in preclinical diagnostic tools, such as New Approach Methods (NAMS), that can supplant animal testing with human cell-based

in vitro assays and

in silico models, which present as a possible resource for more predictive and efficient safety assessments. Moving forward, harmonizing our standards and methods required to evaluate and incorporate new infant formulas into our market in alignment with international guidelines, will be key to safeguarding the nutrition of the nation’s most vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial Support

JTB has received honoraria or travel funds from the Global Organization for EPA and DHA, the global dairy platform, Danone, and research support from the National Cattlemen's Beef Association. MIG has previously served as a scientific advisor for Begin Health and Bobbi. VC has served on the Speaker’s Bureau for Nutricia and Abbott Nutrition. Authors have no additional financial support to declare.

Abbreviations

Adverse outcome pathways (AOP)

Agent-based modeling (ABM)

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

Amino Acid-Based Formulas (AAF)

Codex Alimentarius (Codex)

Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy (CMPA)

European Union (EU)

Extensively Hydrolyzed Formulas (EHF)

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

High-throughput kinetics (HTK)

High-throughput screening (HTS)

Human Milk Fortifier (HMF)

International Council for Harmonization (ICH)

Live biotherapeutic products (LBP)

Microphysiological systems (MPS)

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

New Approach Methods (NAM)

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Structure-activity relationships (SAR)

Parts per billion (ppb)

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)

World Health Organization (WHO)

References

- Video of FDA panel on infant formula, June 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/live/MmE6rlMJdwA).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). 2024. Challenges in Supply, Market Competition, and Regulation of Infant Formula in the United States. The National Academies Press. Washington, DC. [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA, Long-Term National Strategy to Increase the Resiliency of the U.S. Infant Formula Market. https://www.fda.gov/food/infant-formula-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/long-term-national-strategy-increase-resiliency-us-infant-formula-market. Posted January 10, 2025; Accessed June 4, 2025.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Protein Quality and Growth Monitoring Studies: Quality Factor Requirements for Infant Formula. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA, Docket FDA-2020-D-1922. 2023. Guidance for Industry: Recommendations for Submission of Chemical and Technological Data for Direct Food Additive Petitions. Update from March 2009. Posted October 17, 2023.

- Federal Register 81(159). 2016. 54960-55055. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-08-17/pdf/2016-19164.pdf.

- Institute of Medicine. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. National Academies Press. 2009. Washington, DC.

- Neltner T, Maffini M. Generally Recognized as Secret: Chemicals Added to Food in the United States. National Research Defense Council, 2014.

- Redbook 2000. Guidance for Industry and Other Stakeholders: Toxicological Principles for the Safety Assessment of Food Ingredients. https://www.fda.gov/files/food/published/Toxicological-Principles-for-the-Safety-Assessment-of-Food-Ingredients.pdf.

- International Conference on Harmonization. (ICH M3 (R2) Non-clinical safety studies for the conduct of human clinical trials for pharmaceuticals – Scientific guideline. 2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-m3-r2-non-clinical-safety-studies-conduct-human-clinical-trials-pharmaceuticals-scientific-guideline#current-effective-version-9045.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. Updated 2025. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/testing-of-chemicals/test-guidelines.

- U.S. FDA. GRAS Notices. https://www.hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices.

- Rodríguez-Barranco M, Lacasaña M, Aguilar-Garduño C, Alguacil J, Gil F, González-Alzaga, B et al. Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 454-455 (2013) 562-77. [CrossRef]

- Sanders AP, Claus Henn B, Wright RO. Perinatal and Childhood Exposure to Cadmium, Manganese, and Metal Mixtures and Effects on Cognition and Behavior: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2(3) (2015) 284-94. [CrossRef]

- Rahman A, Granberg C, Persson LA. Early life arsenic exposure, infant and child growth, and morbidity: a systematic review. Arch. Toxicol. 91 (2017) 3459-3467. [CrossRef]

- Shea, KM. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. Pediatric exposure and potential toxicity of phthalate plasticizers. Pediatrics. 111(6 Pt 1) (2003) 1467-74. [CrossRef]

- van Beijsterveldt IALP, van Zelst BD, de Fluiter KS, van den Berg SAA, van der Steen M, Hokken-Koelega ACS. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure through infant feeding in early life. Environ. Int. 164 (2022) 107274. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Shi Y, Yang L, Xiao L, Kehoe DK, Gun'ko YK, Boland JJ, et al., Microplastic release from the degradation of polypropylene feeding bottles during infant formula preparation. Nat. Food. 1(11) (2020)746-754. [CrossRef]

- Pajurek M, Mikolajczyk S, Warenik-Bany M. Occurrence and dietary intake of dioxins, furans (PCDD/Fs), PCBs, and flame retardants (PBDEs and HBCDDs) in baby food and infant formula. Sci. Total Environ. 903 (2023) 166590. [CrossRef]

- Hatzidaki E, Pagkalou M, Katsikantami I, Vakonaki E, Kavvalakis M, Tsatsakis AM, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Persistent Organic Pollutants in Infant Formulas and Baby Food: Legislation and Risk Assessments. Foods. 12 (2023) 1697. [CrossRef]

- Soni S, Kurian JW, Kurian C, Chakraborty P, Paari KA. Food additives and contaminants in infant foods: a critical review of their health risk, trends and recent developments. Food Prod. Process Nutr. 6 (2024) 63. [CrossRef]

- Consumer Reports. (2025) https://www.consumerreports.org/babies-kids/baby-formula/baby-formula-contaminants-test-results-a7140095293. Accessed July 30, 2025.

- U.S. FDA. Closer to Zero: Reducing Childhood Exposure to Contaminants from Foods. (2025) https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/closer-zero-reducing-childhood-exposure-contaminants-foods. Accessed , 2025.

- Bair, EC. A Narrative Review of Toxic Heavy Metal Content of Infant and Toddler Foods and Evaluation of United States Policy. Front Nutr. 9 (2022) 919913. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2023) Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Official Journal of the European Union\ 2023;L 119\(103\-57\. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/915/oj/eng. (Amended July 16, 2024; Accessed July 9, 2025).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (2023) P1028 - Infant Formula Products. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/special-purpose-foods/infant-formula-products Published July 26, 2023; Accessed July 19, 2025.

- Government of Canada. (2024) List of Contaminants and Other Adulterating Substances in Foods. In: F. A. N. D. Health Canada's Bureau of Chemical Safety. ed. Ottawa, Canada\: Government of Canada\; 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/chemical-contaminants/contaminants-adulterating-substances-foods.html. (Published December 2024; Modified February 2025; Accessed July 9, 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. (2024) General Standard For Contaminants And Toxins In Food And Feed (Codex Stan 193-1995). Revised 2024. https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/fr/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B193-1995%252FCXS_193e.pdf. (Accessed July 9, 2025).

- Andrade VM, Aschner M, Marreilha Dos Santos AP. Neurotoxicity of metal mixtures. Adv. Neurobiol. 18 (2017) 227-265. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrasco I, Carbonero-Aguilar P, Dahiri B, Moreno IM, Hinojosa M. Comparison between pollutants found in breast milk and infant formula in the last decade: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 875 (2023) 162461. [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. (2020) New Approach Methods Work Plan. https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/epa-new-approach-methods-work-plan-reducing-use-vertebrate-animals-chemical (updated December 2021; Accessed July 9, 2025).

- U.S. FDA. (2017) FDA’S Predictive Toxicology Roadmap. https://www.fda.gov/media/109634/download. (content current as of March 5, 2024; Accessed July 9, 2025).

- Toxicology in the 21st Century (Tox21). (2023) https://tox21.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Tox21_FactSheet_Jan2023.pdf (Accessed July 9, 2025).

- Knudsen TB, Spencer RM, Pierro JD, Baker NC. Computational biology and in silico toxicodynamics. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 23 (2020)1 19-126. [CrossRef]

- European Directive 2006/141/EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2006/141/oj/eng.

- Dietrich R, Jessberger N, Ehling-Schulz M, Märtlbauer E, Granum PE. The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus cereus. Toxins (Basel). 13(2) (2021) 98. [CrossRef]

- Ling N, Forsythe S, Wu Q, Ding Y,. Zhang J, Zeng H, et al., Insights into Cronobacter sakazakii Biofilm Formation and Control Strategies in the Food Industry. Engineering. 6(4) (2020) 393-405. [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA. Infant Formula, Posted May 13, 2025; https://www.fda.gov/food/resources-you-food/infant-formula. Accessed July 28, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).