1. Introduction

Although physicians in ancient times recognized the existence of diseases without a clear organic cause—Hippocrates, around 400 BC, described a condition known as hysteria—it is only in modern medicine that functional disorders have come to be understood not as imaginary, but as the result of complex interactions between the brain, nervous system, and psychological factors. Today, functional disorders are no longer considered exclusively psychogenic but are seen as neurobiologically mediated disturbances of brain networks. Modern diagnostic frameworks now classify functional neurological symptoms as a distinct entity, and their association with maladaptive brain plasticity is the subject of increasing research interest. Why are functional vestibular disorders significant? The answer is simple: among all causes of dizziness, FVDs stand out with a prevalence exceeding 20%, making them the most common cause of dizziness in the adult population. They also represent by far the most frequent form of chronic dizziness, followed by bilateral vestibulopathy, which account for a much smaller proportion of around 5% [

1].

The prevalence of FVDs as the primary cause of vertigo is approximately 10% in neuro-otology centers. Psychiatric comorbidity rates among patients with structural vestibular disorders are significantly higher—nearly 50%—especially in those with vestibular migraine, vestibular paroxysmia, and Ménière’s disease [

2,

3]. Three equally prevalent patterns describe the interaction between psychological and balance disorders: dizziness can arise as a consequence of primary anxiety; vestibular disorders can act as triggers for the development of psychological symptoms; or they may exacerbate pre-existing psychological conditions [

4].

With the introduction of a new, integrative diagnostic framework—which, unlike the traditional dichotomous approach, acknowledges the potential overlap between different diagnostic categories—the Behavioral Subcommittee of the Bárány Society’s Vestibular Disorders Classification Committee established clinical criteria for diagnosing persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD). This diagnosis serves as an umbrella term encompassing several previously described FVDs, including phobic postural vertigo (PPV) [

6], space and motion discomfort (SMD) [

7], visual vertigo (VV) [

8], and chronic subjective dizziness (CSD) [

5,

9]. In the most recent 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), FVDs are not classified separately from structural vestibular disorders; instead, they are grouped within acute, episodic, and chronic vestibular syndromes. According to the Bárány Society, the diagnostic criteria for PPPD include:

Persistent, non-spinning dizziness characterized by sensations of disorientation and unsteadiness, present for most days over a period of at least three months. Symptoms may intensify over time but can also diminish in certain cases.

Although not directly caused by external stimuli, symptoms are exacerbated by three categories of provocation:

Upright posture – symptoms worsen during standing or walking and are significantly reduced when sitting; they typically do not occur while lying down, except in cases of comorbidity (most commonly with vestibular migraine or benign paroxysmal positional vertigo), in which case they follow an episodic pattern.

Hypersensitivity to active or passive motion stimuli, including one’s own movements.

Exposure to large or complex visual stimuli within a wide visual field (e.g., shopping malls, busy streets, screens, striped patterns on floors, walls, or clothing).

Presence of precipitating (“triggering”) factors is essential—these may include acute or recurrent dizziness episodes, or physical and psychiatric illnesses. In cases of acute or recurrent illness, PPPD initially presents intermittently and later becomes persistent. When associated with chronic conditions, PPPD typically develops slowly and progressively.

Symptoms cause significant disability and functional impairment.

Symptoms are not better explained by any other disease or disorder.

The establishment and growing awareness of PPPD diagnostic criteria have significantly bridged a gap in otoneurological diagnostics. Previously, epidemiological data indicated that approximately 25% of dizziness cases in the general population remained undiagnosed; today, that figure has been reduced to just 2%. Although the causes of balance disorders are numerous—numbering in the hundreds—only a few are considered common. These include PPPD, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular migraine, central vestibular syndromes, Ménière’s disease, vestibular neuronitis, and bilateral vestibulopathies. Collectively, these account for over 90% of all cases. In contrast, the remaining 10% comprises hundreds of rare causes, each with a prevalence below 0.6%.

This corresponds to fewer than 5 in 10,000 adults, which meets the European Union’s threshold for defining a rare disease [2,10]. Such statistics underscore the importance of being familiar not only with the most common causes of dizziness, but also with the less common and rare ones, to ensure diagnostic accuracy and resolve complex differential diagnostic dilemmas. “When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras.” This well-known clinical aphorism, originally coined by Dr. Theodore Woodward in the 1940s at the University of Maryland, encourages prioritizing common diagnoses over rare ones [

11]. While we agree with this pragmatic approach, it’s important to acknowledge that zebras—though uncommon—are sometimes encountered in clinical practice. Fortunately, significant advances in vestibular science and diagnostic techniques—particularly the introduction of the video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP)—have greatly improved our ability to timely recognize the “zebras” of vestibular pathology.

2. Materials and Methods

This review ws conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

12]. The objective was to synthesize current knowledge on FVDs, with a specific focus on characterizing UFVDs. Accordingly, the review aims to evaluate current diagnostic frameworks, clinical subtypes, and available treatment strategies.

A systematic literature search was performed using PubMed as the primary database. The search strategy included the following keywords: functional vestibular disorders, persistent postural-perceptual dizziness, voluntary nystagmus, and chronic dizziness. Boolean operators (AND/OR/NOT) were applied, and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were used when applicable.

Articles were selected based on criteria aligned with the PICOS framework (see

Table 1). Eligible studies addressed functional vestibular symptoms in the absence of identifiable organic pathology, described diagnostic and treatment approaches, or proposed unclassified vestibular entities, such as voluntary nystagmus. Only publications in English or German were considered. Studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on structural vestibular disorders—such as Ménière’s disease, BPPV, or vestibular neuritis. Additional exclusion criteria included animal or cadaveric studies, as well as letters, editorials, opinion pieces, and systematic reviews lacking complete primary data.

The literature search in the PubMed database was conducted on July 24, 2025. The initial search used the term “functional vestibular disorders”, applying filters for human studies and publications in English or German. This query yielded 8,499 results.

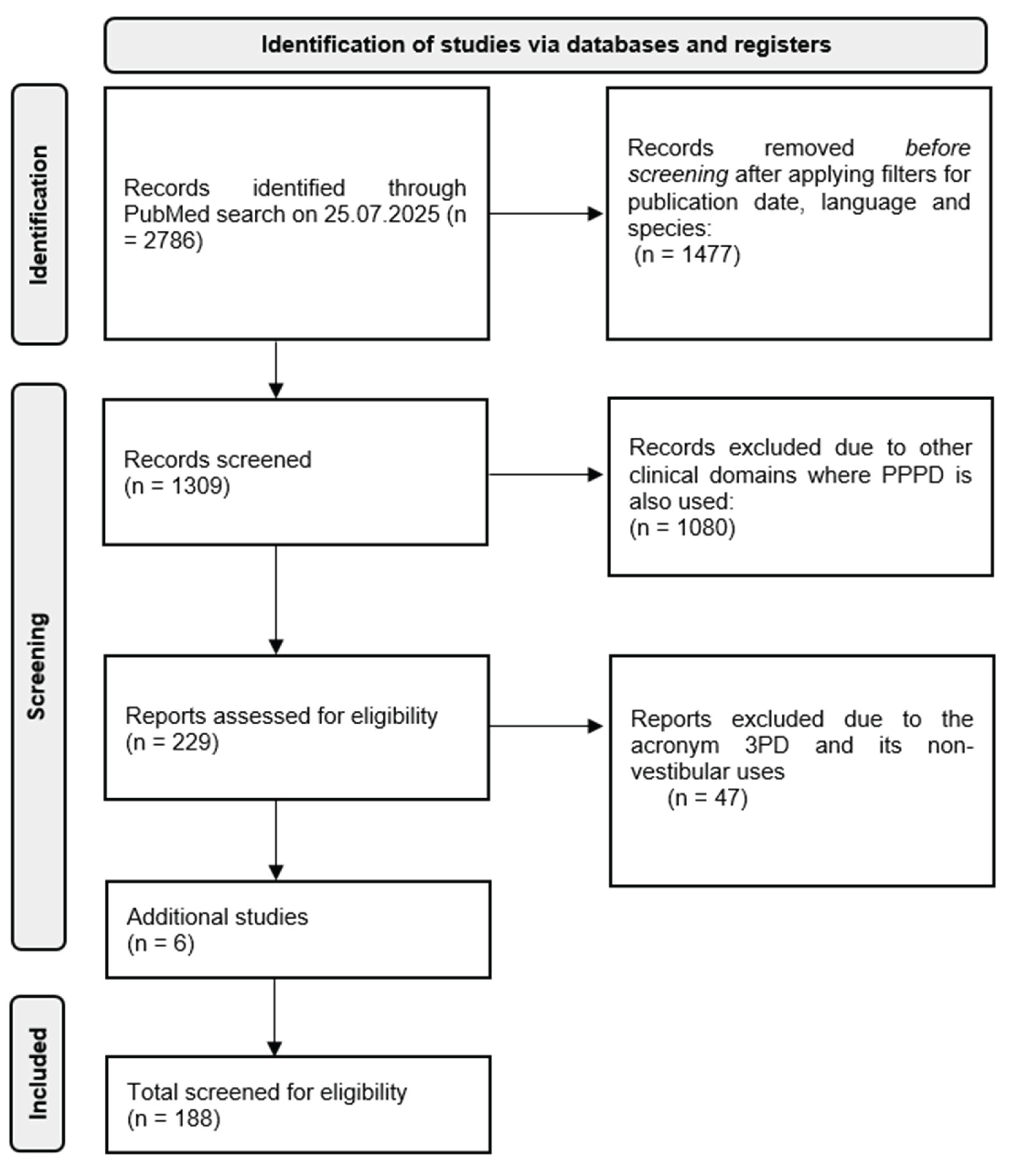

Given the high number of articles and the focus on PPPD as an umbrella diagnosis within the FVDs spectrum, the search was refined in a second stage. This stage centered on the term “persistent postural-perceptual dizziness” and its synonyms and spelling variants: PPPD, 3PD, and persistent postural perceptual dizziness (without hyphens). The unfiltered search yielded 2,786 articles. After applying filters for human studies, English or German language, and a publication date range from 1995 to 2025, the number was reduced to 1,309 articles. To eliminate unrelated results from other clinical domains in which the acronym PPPD is also used (e.g., porokeratosis, pancreatic surgery), Boolean NOT operators were applied. This refinement reduced the results to 229 articles. Further exclusion of non-vestibular uses of the acronym 3PD resulted in a final dataset of 182 articles, with duplicates removed. Subsequently, the search was expanded to include additional terms such as “voluntary nystagmus”, as well as older foundational articles and studies addressing therapeutic approaches. This yielded six additional relevant publications, which were included in the final review.

Figure 1.

Screening for eligible papers according to PRISMA standards.

Figure 1.

Screening for eligible papers according to PRISMA standards.

3. Unclassified Functional Vestibular Disorders

In addition to the four precursor conditions (PPV, SMD, VV and CSD) which together contributed to the development of PPPD as a unifying and overarching diagnostic entity, these conditions can be broadly categorized into three subgroups based on their provoking factors: those exacerbated by complex visual stimuli, by active movements, or by a combination of both [

13]. In parallel with PPPD, there exists a smaller subset of UFVDs. These disorders have a functional (non-organic) etiology but do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for established entities such as PPPD. Unclassified functional vestibular disorders are considerably less common than PPPD and currently remain poorly characterized in terms of clinical evaluation and nosology [

5].

3.1. Chronic, Persistent Dizziness Outside PPPD Criteria

One subtype of UFVDs includes chronic, persistent dizziness, instability, and spatial disorientation that is unrelated to head or body position, activity level, or exposure to external motion and visual stimuli. In cases of chronic dizziness without identifiable triggers, other conditions or nonspecific somatization may be at play. These patients may fall under the broader category of functional balance disorders but do not meet the diagnostic criteria for PPPD, as their symptoms are not clearly associated with motion, visual input, or posture. Instead, their symptoms tend to be tonic and background-like—often described as a “constant fogginess,” “unsteadiness,” or a sense of “disconnection from the environment”—and are present even at rest or during complete inactivity [

14].

In patients with chronic dizziness in the absence of provoking stimuli, a thorough differential diagnosis is essential. Potential etiologies include:

Psychogenic factors, such as anxiety and depression, which are common comorbidities of chronic subjective dizziness and may act as primary drivers of symptoms [

2].

Somatization disorders, which can mimic PPPD but lack a vestibular basis, often presenting with additional functional somatic symptoms [

15].

Dysfunctional somatosensory processing, involving neurological disruption in sensory integration that may result in dizziness, imbalance, and other somatic sensations [

14].

Bilateral vestibulopathy, particularly mild or compensated forms, which may be overlooked if caloric testing or vHIT results are borderline. These patients typically do not report vertigo but describe sensations such as “floating” or “walking on a boat” [

16,

17,

18].

3.2. Experiences of Simultaneous Movement in Different Spatial Planes

A particularly rare but clinically significant manifestation within the UFVDs spectrum involves complex sensations of simultaneous self-motion across multiple spatial planes. Patients describe these experiences as concurrent rotation around different axes—for example, “I spin simultaneously backward and upward.” Such sensations may present as a swirling of the entire visual field or as kaleidoscopic environmental motion, occasionally accompanied by altered gravitational perception or even feelings of disembodiment.

The underlying neurophysiological mechanism is presumed to involve dysintegration of multisensory input at the level of the vestibular nuclei, or disrupted processing within higher vestibulo-cortical pathways, particularly in the parieto-insular vestibular cortex and the temporoparietal junction [

19,

20]. In some cases, these phenomena may reflect vestibulo-perceptual dissociation, in which the expected congruence among sensory modalities—vestibular, proprioceptive, and visual—becomes unstable or fragmented [

21].

Clinical observations suggest that such perceptual experiences often co-occur with chronic somatic conditions such as chronic pain, fibromyalgia, or chronic fatigue syndrome, where disruptions in body schema and interoceptive awareness are commonly observed [

22]. Emotional and attentional factors—such as heightened vigilance or altered interoception—may also contribute to the emergence of these perceptual instabilities [

23,

24].

Although still poorly classified, these complex multisensory distortions are critical to advancing our understanding of functional vestibular disorders, particularly in their relationship to bodily self-consciousness and multisensory integration.

3.3. Voluntary Nystagmus

A third unclassified functional vestibular disorder is voluntary nystagmus (VN). As early as the mid-19th century, some authors observed that certain individuals could voluntarily induce nystagmus-like eye movements without external stimuli. Patients typically induce these eye movements consciously—most often horizontal—accompanied by oscillopsia and a sensation of instability or discomfort.

Approximately 5–8% of the healthy population can produce voluntary nystagmus, usually during convergence. It is not associated with vestibular or neurological pathology [

25]. The phenomenon likely originates in supranuclear control mechanisms of eye movements, particularly those involved in saccades and fine tracking. VN can be distinguished from pathological forms of nystagmus by its specific characteristics: high frequency (10–25 Hz), low amplitude (up to 6°), relatively short duration (up to 35 seconds), and its occurrence in otherwise healthy individuals.

Although the underlying mechanism is presumed to be neurological, psychological factors may also play a role [

26]. This is supported by case reports, including three individuals with VN who were associated with military service [

27]. Voluntary nystagmus appears to occur more frequently among relatives, suggesting a possible autosomal dominant genetic predisposition.

It is crucial to differentiate VN from pathological nystagmus to avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures or misinterpretation of findings.

3.4. General Characteristics of Unclassified Functional Vestibular Disorders

Unclassified functional vestibular disorders are characterized by dizziness, imbalance, or instability that are neurophysiologically reversible and not caused by structural lesions of the vestibular system. These conditions are frequently associated with anxiety, somatization, stress, or maladaptive sensorimotor integration. Patients often exhibit hypersensitivity to movement, visual stimuli, or specific environments such as shopping malls, car rides, or high places. Symptoms may present as constant, intermittent, or situational.

How can they be distinguished from persistent postural-perceptual dizziness?

Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness is a well-defined clinical syndrome characterized by chronic dizziness lasting three months or more, with symptom exacerbation during movement, exposure to complex visual stimuli, and while standing. In contrast, UFVDs do not meet all PPPD diagnostic criteria. These disorders may present with shorter duration, irregular symptom patterns, differing triggers, and lower consistency. They often overlap with psychogenic dizziness, unspecified post-traumatic dizziness, or conversion disorder.

4. Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of FVDs requires thorough exclusion of organic vestibular diseases. A wide range of vestibular and audiological laboratory tests are essential for this purpose, including videonystagmography, pure tone audiometry, vHIT, and VEMP. Posturographic assessments may reveal discrepancies in multisensory integration—such as deviations from verticality in the sensory organization test—indicating dysfunction in the integration of visual, somatosensory, and vestibular inputs [

28].

In addition to objective testing, psychological assessment tools, such as the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), are valuable for identifying comorbid anxiety and somatoform disorders that frequently coexist with FVDs.

5. Treatment

Treatment of FVDs is multimodal and complex. Although there is general consensus on managing PPPD and other FVDs through patient counseling and education, psychotropic medications, vestibular rehabilitation (VR), and psychotherapeutic interventions [

29,

30,

31], the most common outcome is symptom reduction rather than complete resolution [

32]. Unfortunately, no large-scale, long-term studies have yet definitively evaluated the effectiveness of individual treatment components or their combinations for FVDs.

5.1. Pharmacotherapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used in the treatment of FVDs [

33]. Initially, these drugs were thought to have limited efficacy because dizziness is a frequent side effect. However, numerous subsequent studies have demonstrated their benefit despite this [

34,

35,

36]. Both SSRIs and SNRIs alleviate dizziness by increasing serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the synaptic cleft, thereby reducing the sensitivity of the vestibular nuclei.

Selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have certain advantages over SSRIs, as they also increase norepinephrine levels, which may be particularly beneficial in patients with fatigue, low energy, and chronic pain. However, SNRIs may cause side effects such as increased blood pressure, sweating, nausea, and insomnia, especially at higher doses.

Treatment with these medications results in approximately a 50% reduction of primary symptoms in 60–70% of patients. Comorbid anxiety and depression also significantly improve with their use. Initial dosing typically starts at one-quarter to one-half of the usual antidepressant dose, gradually titrated to standard levels. Higher doses may be required in patients with psychiatric comorbidities or predominant anxiety symptoms, sometimes up to twice the typical dose used for depression. Treatment duration is generally recommended for 3–4 months.

Short-term benzodiazepine use may be beneficial for patients with pronounced comorbid anxiety or depression but is otherwise of limited value. High-potency benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam, clonazepam) are preferred over low-potency agents (e.g., diazepam, oxazepam) due to greater efficacy and lower risk of addiction. Treatment should start at the lowest effective dose and be gradually increased until symptoms are controlled. Continuous use beyond six months is not recommended due to tolerance and dependence risks.

Non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics, such as buspirone—a 5-HT1A receptor agonist—should also be considered. Buspirone does not cause tolerance or dependence.

5.2. Vestibular Rehabilitation

Numerous clinical studies have demonstrated the benefits of VR in patients with dizziness. However, only a few prospective clinical studies have specifically included patients with FVDs and shown symptom reduction following VR [

37,

38]. In these cases, greater improvements were observed for symptoms triggered by self-movements compared to those provoked by visual motion in the environment.

Vestibular rehabilitation for FVDs focuses on identifying provoking movements and demonstrating to patients that their fear of performing these movements is unfounded. Classical adaptation and substitution exercise protocols are generally unsuitable for functional vestibular disorders. Instead, individually tailored habituation and/or exposure exercises are employed, involving real-life provocative stimuli and situations such as escalators, elevators, walking at heights, boat rides, or highway driving. This exposure-based approach integrates physical treatment—such as balance and postural control exercises—with psychological components aimed at reducing fear and sensitivity to symptom-provoking movements. This process is crucial for habituation and reducing vestibular hypersensitivity.

Recently, virtual reality has been increasingly explored as a tool for exposure therapy in FVDs. Virtual reality allows controlled and gradual exposure to challenging visual and vestibular stimuli within a safe environment. Some studies suggest that virtual reality may benefit patients with pronounced fear or those who avoid real-life exposure; however, current evidence is insufficient to consider it a replacement for real-world exposure, which remains the gold standard.

Conditioning exercises targeting impaired posture during standing and walking may also be beneficial. Sessions should be performed in sets of five repetitions, at least twice daily. Moderate aerobic activity or a walking program is recommended, as greater physical activity correlates with improved recovery prospects. It is important to start with simpler exercises that are gradually intensified to avoid symptom exacerbation, which often leads patients to discontinue therapy prematurely. The best outcomes are typically achieved after 3–6 months of consistent exercise.

5.3. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The cognitive-behavioral model of PPPD, developed in 2017, expands on Staab’s model by integrating biopsychosocial factors into the conceptualization of health anxiety [

39]. Similar to acute vestibular syndromes, CBT shows promising results in the treatment of PPPD. Therapeutic interventions based on the fundamental theoretical principles of CBT have proven effective in addressing most symptoms related to anxiety and depression, which are highly prevalent conative components of FVDs. Therefore, it is unsurprising that CBT is effective in treating these conditions. However, participation in cognitive-behavioral therapy can sometimes be hindered by the physical symptoms patients experience [

29].

Cognitive-behavioral therapy combines cognitive and behavioral therapies, each retaining its specific focus. Cognitive therapy targets inappropriate or harmful cognitions, such as negative automatic thoughts, core beliefs, and cognitive schemas. Behavioral therapy, based on the premise that disease symptoms are learned, uses learning processes to eliminate them. Cognitive therapy initially modifies cognition and, in the long term, behavior; behavioral therapy first changes behavior, with cognition following later. The combined application in CBT facilitates faster improvement and longer remission.

Key CBT techniques include changing negative automatic thoughts, refocusing attention, reattribution, systematic and gradual exposure (desensitization), sudden exposure (flooding), biofeedback, among others. The exposure technique, as in other anxiety disorders, has a stronger therapeutic effect than cognitive techniques alone because it enables experiential testing and restructuring of catastrophic beliefs.

6. Prognosis

Despite verified efficacy in treating symptoms of FVDs, SSRIs/SNRIs, vestibular rehabilitation, cognitive-behavioral therapy and exposure therapy have not proven effective in maintaining long-term therapeutic effects. Patients sometimes hold negative beliefs about their prognosis. Therefore, CBT should include education emphasizing that complete remission of symptoms may not occur, but significant improvement is achievable [

31] Prognosis varies significantly between patients with and without comorbidities. In patients without comorbidities, who constitute the majority (60–80%), improvement occurs in more than half of cases following persistent therapy lasting 3–4 months. Conversely, patients with comorbidities (20–40%) often show little progress despite therapy, even after 6 months. It should be noted that the majority (over 70%) of patients continue to experience symptoms and have a significantly impaired quality of life several years after disease onset [

40,

41].

7. Conclusions

Functional vestibular disorders, particularly PPPD, represent a significant yet often underrecognized cause of dizziness. Advances in diagnostic criteria and understanding of brain-vestibular interactions have improved identification and reduced diagnostic uncertainty. However, UFVDs remain underexplored, highlighting the need for further clinical research and nuanced diagnostic approaches. Awareness of both common and rare balance disorders is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and A.K.; methodology, S.M. and L.D.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M., T.M., and A.K.; formal analysis, T.M. and P.D.; investigation, S.M., Z.B., and L.D.; resources, S.M. and L.D.; data curation, S.M. and T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and Z.B.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and A.K.; supervision, A.K. and P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

FVDs — functional vestibular disorders

UFVDs — unclassified functional vestibular disorders

PPPD — persistent postural-perceptual dizziness

PPV — phobic postural vertigo

SMD — space and motion discomfort

VV — visual vertigo

CSD — chronic subjective dizziness

VN — voluntary nystagmus

ICD-11 — 11th International Classification of Diseases

BPPV — benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

vHIT — video Head Impulse Test

VEMP — vestibular evoked myogenic potentials

CBT — cognitive-behavioral therapy

VR — vestibular rehabilitation

References

- Strupp, M.; Thurtell, M. J.; Shaikh, A. G.; Brandt, T.; Zee, D. S.; Leigh, R. J. Pharmacotherapy of Vestibular and Ocular Motor Disorders, Including Nystagmus. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, C.; Tschan, R.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Dieterich, M. Who Is at Risk for Ongoing Dizziness and Psychological Strain after a Vestibular Disorder? Neuroscience 2009, 164, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, M.; Staab, J. P. Functional Dizziness: From Phobic Postural Vertigo and Chronic Subjective Dizziness to Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2017, 30, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, J. P.; Ruckenstein, M. J. ; Ruckenstein, M. J. Expanding the Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Dizziness. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 133, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Horii, A.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD): Consensus Document of the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders. J. Vestib. Res. 2017, 27, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. Phobischer Attacken Schwankschwindel. Ein Neues Syndrom. Munch. Med. Wochenschr. 1986, 128, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, R. G.; Woody, S. R.; Clark, D. B.; Lilienfeld, S. O.; Hirsh, B. E.; Durrant, J. D.; Furman, J. M. Discomfort with Space and Motion: A Possible Marker of Vestibular Dysfunction Assessed by the Situational Characteristics Questionnaire. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1993, 15, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, A. M. Visual Vertigo Syndrome: Clinical and Posturography Findings. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1995, 59, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staab, J. P.; Ruckenstein, M. J.; Amsterdam, J. D. A Prospective Trial of Sertraline for Chronic Subjective Dizziness. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. VIIIth Nerve Vascular Compression Syndrome: Vestibular Paroxysmia. Baillieres Clin. Neurol. 1994, 3, 565–575. [Google Scholar]

- Sotos, J. G. Zebra Cards: An Aid to Obscure Diagnoses; Mt. Vernon Book Systems: Mt. Vernon, VA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-9818193-0-3. [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 2021.

- Yagi, C.; Morita, Y.; Kitazawa, M.; et al. Subtypes of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 652366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkirov, S.; Hoeritzauer, I.; Colvin, L.; Carson, A.; Stone, J. Functional Neurological Disorders: Advances in Understanding and Management. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, P.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W. Management of Functional Somatic Syndromes and Bodily Distress. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingler, V. C.; et al. Causative Factors and Epidemiology of Bilateral Vestibulopathy in 255 Patients. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 66, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucieer, F.; Vonk, P.; Guinand, N.; Stokroos, R.; Kingma, H.; van de Berg, R. Full Spectrum of Reported Symptoms of Bilateral Vestibulopathy Needs Further Investigation—A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupp, M.; Kim, J. S.; Murofushi, T.; Straumann, D.; Jen, J. C.; Rosengren, S. M.; Della Santina, C. C.; Kingma, H. Bilateral Vestibulopathy: Diagnostic Criteria Consensus Document of the Classification Committee of the Bárány Society. J. Vestib. Res. 2017, 27, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, C.; Blanke, O. The Thalamocortical Vestibular System in Animals and Humans. Brain Res. Rev. 2011, 67, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. Perception of Self-Motion: The Vestibular System and the Importance of Visual Input. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1999, 12, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, W.; Porten, K.; Gass, K.; Dieterich, M.; Brandt, T.; Tschan, R. Body Representation Disturbances in Functional Dizziness: A Review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 151, 110641. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A. D. Interoception: The Sense of the Physiological Condition of the Body. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003, 13, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A. K.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H. D. An Interoceptive Predictive Coding Model of Conscious Presence. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchley, H. D.; Garfinkel, S. N. Interoception and Emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, R. J.; Zee, D. S. The Neurology of Eye Movements, 5th ed.; Contemporary Neurology Series; Oxford Academic: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn, J. R. Incidence and Characteristics of Voluntary Nystagmus. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1978, 41, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, H. Voluntary Nystagmus. Neurology 1973, 23, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söhsten, E.; Moraes, R.; Tavares, C.; Lima, I.; Almeida, R. Posturographic Profile of Patients with Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness on the Sensory Organization Test. J. Vestib. Res. 2016, 26, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaski, D. Neurological Update: Dizziness. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 1864–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axer, H.; Finn, S.; Wassermann, A.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Klingner, C. M.; Witte, O. W. Multimodal Treatment of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suica, Z.; Behrendt, F.; Ziller, C.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Treatments in Patients with Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness: A Systematic Review and Effect Sizes Analyses. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1426566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterston, J.; Chen, L.; Mahony, K.; Gencarelli, J.; Stuart, G. Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness: Precipitating Conditions, Co-morbidities and Treatment with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 795516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, R.; Rust, H.; Baumann, T.; Gürkov, R.; Straumann, D.; Kraut, K. Treatment of Dizziness: An Interdisciplinary Update. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staab, J. P.; Ruckenstein, M. J.; Solomon, D.; Shepard, N. T. Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Dizziness with Psychiatric Symptoms. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002, 128, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horii, A.; Uno, A.; Kitahara, T.; Mitani, K.; Takeda, N.; Kubo, T. Effects of Fluvoxamine on Anxiety, Depression, and Subjective Handicaps of Chronic Dizziness Patients with or without Neuro-Otologic Diseases. J. Vestib. Res. 2007, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N. M.; Parker, S. W.; Wernick-Robinson, M.; Beevers, C. G.; Wilhelm, S.; Rauch, S. L.; Pollack, M. H. Fluoxetine for Vestibular Dysfunction and Anxiety: A Prospective Pilot Study. Psychosomatics 2005, 46, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. J.; Goetting, J. C.; Staab, J. P.; Shepard, N. T. Retrospective Review and Telephone Follow-Up to Evaluate a Physical Therapy Protocol for Treating Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness: A Pilot Study. J. Vestib. Res. 2015, 25, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, A.; Zimatore, G.; Badaracco, C.; De Angelis, E.; Tufarelli, D. Effects of Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy on Emotional Aspects in Chronic Vestibular Patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, M. G.; Cane, D. A. A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2017, 24, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Redfern, M. S. Psychological Factors Influencing Recovery from Balance Di-sorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2001, 15, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Breuer, P.; Thomalske, C.; Hoffmann, S. O.; Hopf, H. C. Anxiety Disorders and Other Psychiatric Subgroups in Patients Complaining of Dizziness. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).