Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Targets of Mycobacteria for Antitubercular Drugs Discovery

2.1. Cell Wall of M. tuberculosis

2.2. Nucleic Acids

2.2.1. Purine and Pyrimidine Ribonucleotide Synthesis

2.2.2. Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Replication

2.2.3. DNA Repair

2.3. Protein Synthesis (RNA Translation)

2.4. Energy Metabolism

3. Natural Products with Potent Antimycobacterial Activities

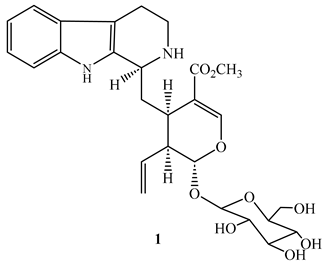

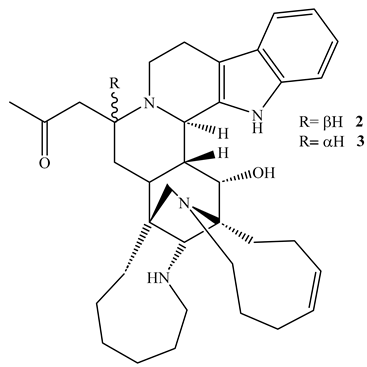

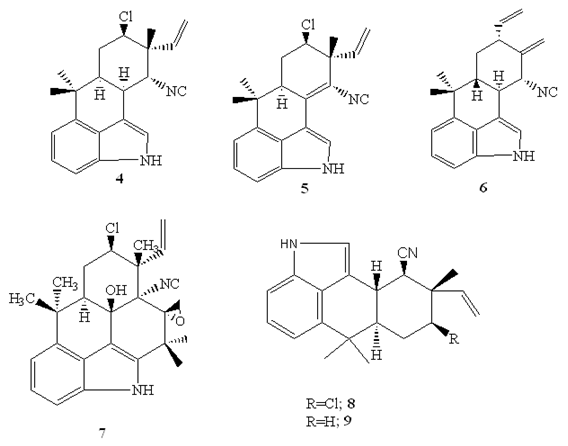

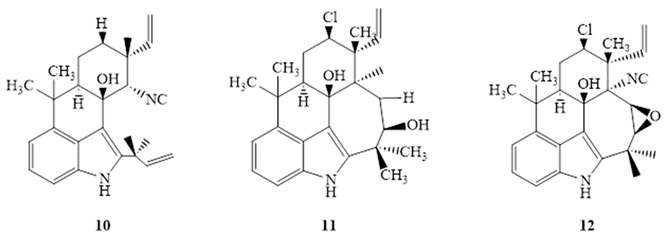

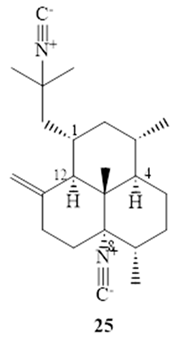

3.1. Alkaloids

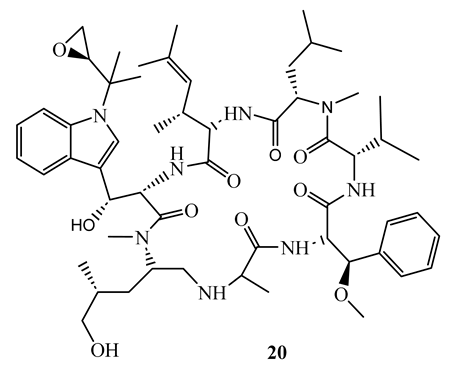

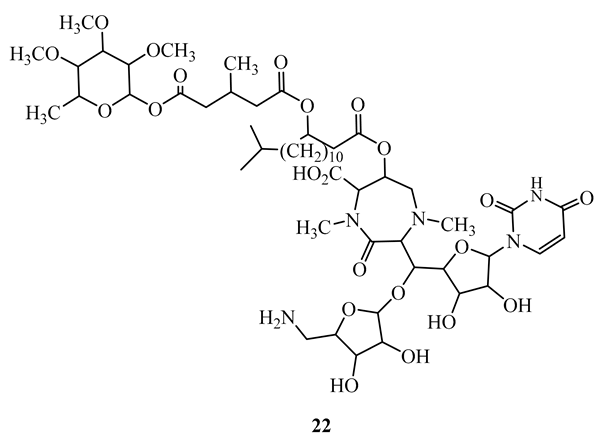

3.2. Simple Amides and Peptides

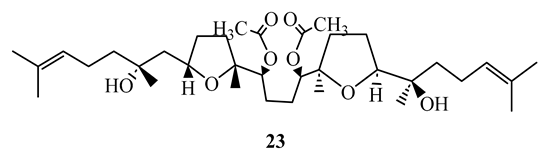

3.3. Terpenoids

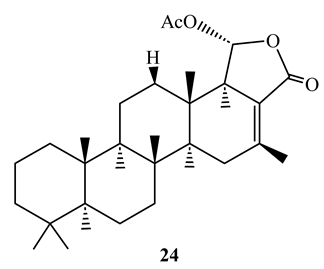

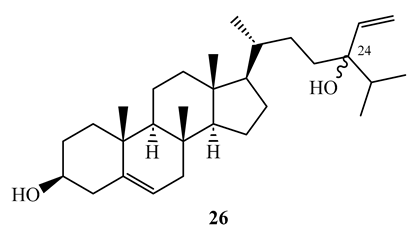

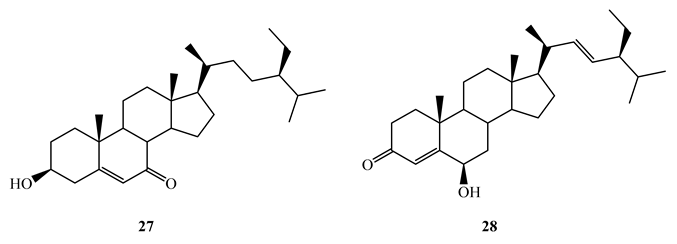

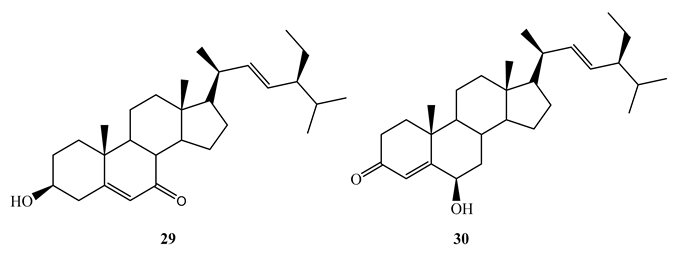

3.4. Steroids

3.5. Miscellaneous Compounds

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrahams, K.A.; Besra, G.S. Mycobacterial Drug Discovery. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2023.

- Bueno-Sánchez, J.G.; Martínez-Morales, J.R.; Stashenko, E.E.; Ribón, W. Anti-Tubercular Activity of Eleven Aromatic and Medicinal Plants Occurring in Colombia. Biomed. Rev. Inst. Nac. Salud 2009, 29, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Amzel, L.M. Tuberculosis Drug Targets. Curr. Drug Targets 2002, 3, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.D.; Zumla, A.I. Tuberculosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2011, 378, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, A.; Rehman, G.; Ul-Islam, M.; Khattak, W.A.; Lee, Y.S. Challenges in the Development of Drugs for the Treatment of Tuberculosis. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorte, R. Exploration of Nature’s Chemodiversity: The Role of Secondary Metabolites as Leads in Drug Development. Drug Discov. Today 1998, 3, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kana, B.D.; Karakousis, P.C.; Parish, T.; Dick, T. Future Target-Based Drug Discovery for Tuberculosis? Tuberculosis 2014, 94, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrish, E.; Sit, C.S.; Cao, S.; Kandror, O.; Spoering, A.; Peoples, A.; Ling, L.; Fetterman, A.; Hughes, D.; Bissell, A.; et al. Lassomycin, a Ribosomally Synthesized Cyclic Peptide, Kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Targeting the ATP-Dependent Protease ClpC1P1P2. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Trifonov, L.; Yadav, V.D.; Barry, C.E.; Boshoff, H.I. Tuberculosis Drug Discovery: A Decade of Hit Assessment for Defined Targets. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, C.E. Interpreting Cell Wall “virulence Factors” of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetye, G.S.; Franzblau, S.G.; Cho, S. New Tuberculosis Drug Targets, Their Inhibitors, and Potential Therapeutic Impact. Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 68–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hoyos, M.; Perez-Herran, E.; Gulten, G.; Encinas, L.; Álvarez-Gómez, D.; Alvarez, E.; Ferrer-Bazaga, S.; García-Pérez, A.; Ortega, F.; Angulo-Barturen, I.; et al. Antitubercular Drugs for an Old Target: GSK693 as a Promising InhA Direct Inhibitor. EBioMedicine 2016, 8, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaniço, A.; Moreira, R.; Lopes, F. Drug Discovery in Tuberculosis. New Drug Targets and Antimycobacterial Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 150, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, H.J.; Cheema, S.; Lal, S.; Raut, C.P.; Kalia, V.C. In Search of Drug Targets for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2007, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, M.R.; Morbidoni, H.R.; Alland, D.; Sneddon, S.F.; Gourlie, B.B.; Staveski, M.M.; Leonard, M.; Gregory, J.S.; Janjigian, A.D.; Yee, C.; et al. Targeting Tuberculosis and Malaria through Inhibition of Enoyl Reductase: Compound Activity and Structural Data. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 20851–20859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozwarski, D.A.; Vilchèze, C.; Sugantino, M.; Bittman, R.; Sacchettini, J.C. Crystal Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Enoyl-ACP Reductase, InhA, in Complex with NAD+ and a C16 Fatty Acyl Substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 15582–15589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirude, P.S.; Madhavapeddi, P.; Naik, M.; Murugan, K.; Shinde, V.; Nandishaiah, R.; Bhat, J.; Kumar, A.; Hameed, S.; Holdgate, G.; et al. Methyl-Thiazoles: A Novel Mode of Inhibition with the Potential to Develop Novel Inhibitors Targeting InhA in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8533–8542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida Da Silva, P.E.A.; Palomino, J.C. Molecular Basis and Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Classical and New Drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 1417–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Xiang, X.; Xie, J. Crucial Components of Mycobacterium Type II Fatty Acid Biosynthesis (Fas-II) and Their Inhibitors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 360, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miggiano, R.; Morrone, C.; Rossi, F.; Rizzi, M. Targeting Genome Integrity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: From Nucleotide Synthesis to DNA Replication and Repair. Molecules 2020, 25, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biochemical and Structural Investigations on Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate Synthetase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. PLoS ONE. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0175815 (accessed on 11 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Breda, A.; Martinelli, L.K.B.; Bizarro, C.V.; Rosado, L.A.; Borges, C.B.; Santos, D.S.; Basso, L.A. Wild-Type Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate Synthase (PRS) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A Bacterial Class II PRS? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.F.; Evans, J.C.; Mizrahi, V. Nucleotide Metabolism and DNA Replication. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedstrom, L. IMP Dehydrogenase: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2903–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditse, Z.; Lamers, M.H.; Warner, D.F. DNA Replication in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-C.; Chen, F.-C. The Evolutionary Landscape of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Genome. Gene 2013, 518, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus, M.A.; Gerrick, E.R.; Xu, W.; Park, S.W.; Long, J.E.; Boutte, C.C.; Rubin, E.J.; Schnappinger, D.; Ehrt, S.; Fortune, S.M.; et al. Comprehensive Essentiality Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Genome via Saturating Transposon Mutagenesis. mBio 2017, 8, e02133-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiche, M.A.; Warner, D.F.; Mizrahi, V. Targeting DNA Replication and Repair for the Development of Novel Therapeutics against Tuberculosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durbach, S.I.; Springer, B.; Machowski, E.E.; North, R.J.; Papavinasasundaram, K.G.; Colston, M.J.; Böttger, E.C.; Mizrahi, V. DNA Alkylation Damage as a Sensor of Nitrosative Stress in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, V.; Andersen, S.J. DNA Repair in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. What Have We Learnt from the Genome Sequence? Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 29, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sharma, S.; Kaushal, P.S. Protein Synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a Potential Target for Therapeutic Interventions. Mol. Aspects Med. 2021, 81, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Chang, J.; Cui, Z.; Li, X.; Meng, R.; Duan, L.; Thongchol, J.; Jakana, J.; Huwe, C.M.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Zhang, J. Structural Insights into Species-Specific Features of the Ribosome from the Human Pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, 10884–10894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.N. Ribosome-Targeting Antibiotics and Mechanisms of Bacterial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehlsgaard, J.; Douthwaite, S. The Bacterial Ribosome as a Target for Antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bald, D.; Koul, A. Respiratory ATP Synthesis: The New Generation of Mycobacterial Drug Targets? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 308, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bald, D.; Villellas, C.; Lu, P.; Koul, A. Targeting Energy Metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a New Paradigm in Antimycobacterial Drug Discovery. mBio 2017, 8, e00272-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, S.; Hung, D.T. The Expanding Diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Drug Targets. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.; Kouznetsov, V. Antimycobacterial Susceptibility Testing Methods for Natural Products Research. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J.H.; Ferraro, M.J. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: A Review of General Principles and Contemporary Practices. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2009, 49, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orme, I.; Program, T.D.S. Search for New Drugs for Treatment of Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1943–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, O.A.; Udo, E.E.; Varghese, R. Antimycobacterial Activities of Novel 5-(1H-1,2,3-Triazolyl)Methyl Oxazolidinones. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 289136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Junior, A.R.; Oliveira Ferreira, R.; de Souza Passos, M.; da Silva Boeno, S.I.; Glória das Virgens, L.d.L.; Ventura, T.L.B.; Calixto, S.D.; Lassounskaia, E.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Braz-Filho, R.; et al. Antimycobacterial and Nitric Oxide Production Inhibitory Activities of Triterpenes and Alkaloids from Psychotria nuda (Cham. & Schltdl.) Wawra. Mol. 2019, 24, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Hu, J.-F.; Kazi, A.B.; Li, Z.; Avery, M.; Peraud, O.; Hill, R.T.; Franzblau, S.G.; Zhang, F.; Schinazi, R.F.; et al. Manadomanzamines A and B: A Novel Alkaloid Ring System with Potent Activity against Mycobacteria and HIV-1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13382–13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lantvit, D.; Hwang, C.H.; Kroll, D.J.; Swanson, S.M.; Franzblau, S.G.; Orjala, J. Indole Alkaloids from Two Cultured Cyanobacteria, Westiellopsis Sp. and Fischerella muscicola. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5290–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Krunic, A.; Chlipala, G.; Orjala, J. Antimicrobial Ambiguine Isonitriles from the Cyanobacterium Fischerella ambigua. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Krunic, A.; Santarsiero, B.D.; Franzblau, S.G.; Orjala, J. Hapalindole-Related Alkaloids from the Cultured Cyanobacterium Fischerella ambigua. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveh, A.; Carmeli, S. Antimicrobial Ambiguines from the Cyanobacterium Fischerella Sp. Collected in Israel. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

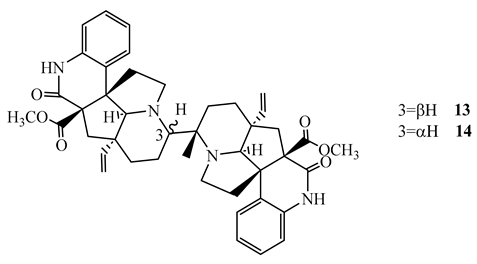

- Gao, X.-H.; Fan, Y.-Y.; Liu, Q.-F.; Cho, S.-H.; Pauli, G.F.; Chen, S.-N.; Yue, J.-M. Suadimins A-C, Unprecedented Dimeric Quinoline Alkaloids with Antimycobacterial Activity from Melodinus suaveolens. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7065–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

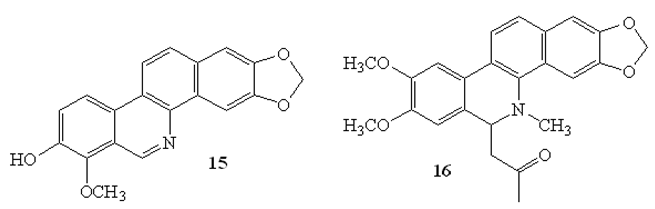

- Luo, X.; Pires, D.; Aínsa, J.A.; Gracia, B.; Duarte, N.; Mulhovo, S.; Anes, E.; Ferreira, M.-J.U. Zanthoxylum capense Constituents with Antimycobacterial Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro and ex vivo within Human Macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

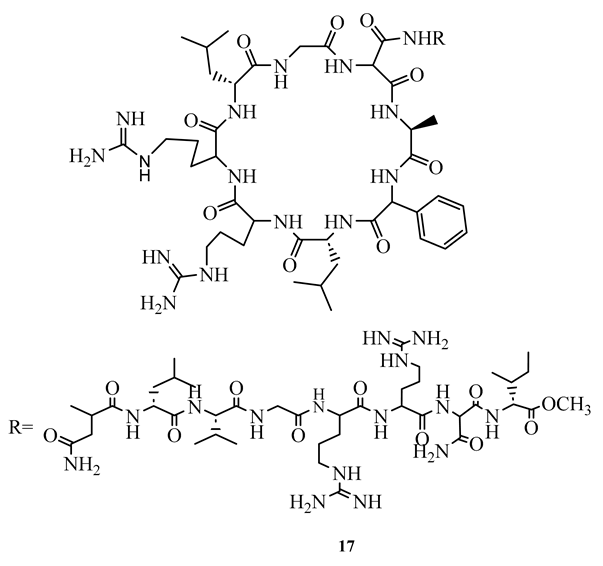

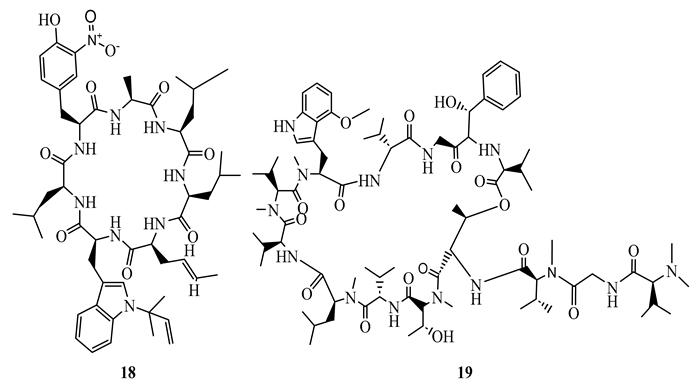

- Choules, M.P.; Wolf, N.M.; Lee, H.; Anderson, J.R.; Grzelak, E.M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R.; Gao, W.; McAlpine, J.B.; Jin, Y.-Y.; et al. Rufomycin Targets ClpC1 Proteolysis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02204-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Kim, J.-Y.; Chen, S.-N.; Cho, S.-H.; Choi, J.; Jaki, B.U.; Jin, Y.-Y.; Lankin, D.C.; Lee, J.-E.; Lee, S.-Y.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of the Tuberculosis Drug Lead Ecumicin. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6044–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Nakagawa, N.; Doi, N.; Hattori, S.; Naganawa, H.; Hamada, M. Caprazamycin B, a Novel Anti-Tuberculosis Antibiotic, from Streptomyces Sp. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeno, S.I.S.; Passos, M.d.S.; Félix, M.; Calixto, S.D.; Júnior, A.R.C.; Barbosa Siqueira, L.F.; Muzitano, M.F.; Braz-Filho, R.; Vieira, I.J.C. Antimycobacterial Activity of Milemaronol, a New Squalene-Type Triterpene, and Other Isolate? Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20925589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonganuchitmeta, S.; Yuenyongsawad, S.; Keawpradub, N.; Plubrukarn, A. Antitubercular Sesterterpenes from the Thai Sponge Brachiaster Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledroit, V.; Debitus, C.; Ausseil, F.; Raux, R.; Menou, J.-L.; Hill, B. Heteronemin as a Protein Farnesyl Transferase Inhibitor. Pharm. Biol. 2004, 42, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, K.; Prudhomme, J.; Le Roch, K.G.; Franzblau, S.G.; Rodríguez, A.D. Natural Product-Based Synthesis of Novel Anti-Infective Isothiocyanate- and Isoselenocyanate-Functionalized Amphilectane Diterpenes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, G.A.; Franzblau, S.G.; Montenegro, G.; Hoffmann, J.J.; Maiese, W.M.; Timmermann, B.N. Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Growth by Saringosterol from Lessonia nigrescens. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Lugo, M.-T.; Wang, Y.; Franzblau, S.G.; Suarez, E.; Timmermann, B.N. Antitubercular Sterols from Thalia multiflora Horkel Ex Koernicke. Phytother. Res. PTR 2005, 19, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

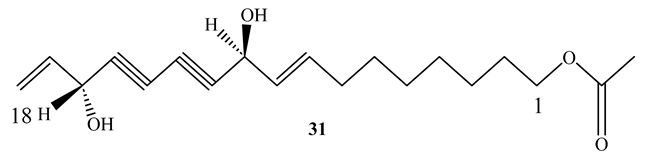

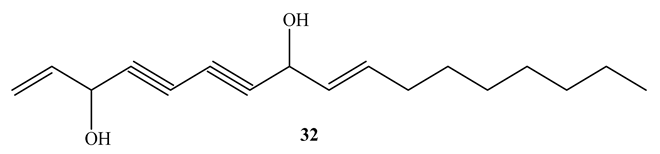

- Deng, S.; Wang, Y.; Inui, T.; Chen, S.-N.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Cho, S.; Franzblau, S.G.; Pauli, G.F. Anti-TB Polyynes from the Roots of Angelica sinensis. Phytother. Res. PTR 2008, 22, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

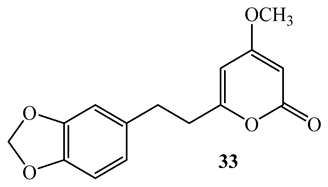

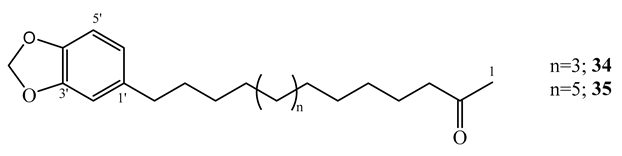

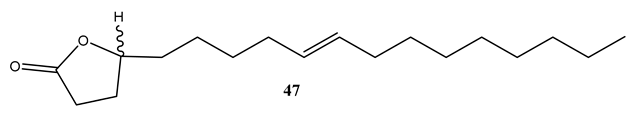

- Mata, R.; Morales, I.; Pérez, O.; Rivero-Cruz, I.; Acevedo, L.; Enriquez-Mendoza, I.; Bye, R.; Franzblau, S.; Timmermann, B. Antimycobacterial Compounds from Piper sanctum. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1961–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wube, A.A.; Bucar, F.; Gibbons, S.; Asres, K. Sesquiterpenes from Warburgia ugandensis and Their Antimycobacterial Activity. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

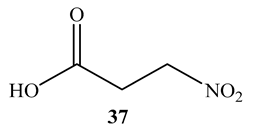

- Chomcheon, P.; Wiyakrutta, S.; Sriubolmas, N.; Ngamrojanavanich, N.; Isarangkul, D.; Kittakoop, P. 3-Nitropropionic Acid (3-NPA), a Potent Antimycobacterial Agent from Endophytic Fungi: Is 3-NPA in Some Plants Produced by Endophytes? J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

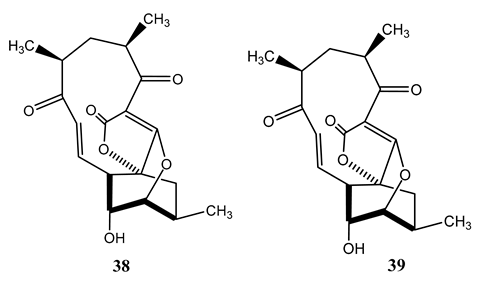

- Goodfellow, M.; Stach, J.E.M.; Brown, R.; Bonda, A.N.V.; Jones, A.L.; Mexson, J.; Fiedler, H.-P.; Zucchi, T.D.; Bull, A.T. Verrucosispora Maris Sp. Nov., a Novel Deep-Sea Actinomycete Isolated from a Marine Sediment Which Produces Abyssomicins. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2012, 101, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

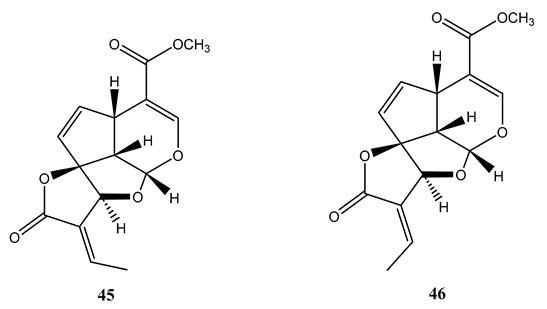

- Freundlich, J.S.; Lalgondar, M.; Wei, J.-R.; Swanson, S.; Sorensen, E.J.; Rubin, E.J.; Sacchettini, J.C. The Abyssomicin C Family as in vitro Inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberc. Edinb. Scotl. 2010, 90, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bister, B.; Bischoff, D.; Ströbele, M.; Riedlinger, J.; Reicke, A.; Wolter, F.; Bull, A.T.; Zähner, H.; Fiedler, H.-P.; Süssmuth, R.D. Abyssomicin C-A Polycyclic Antibiotic from a Marine Verrucosispora Strain as an Inhibitor of the p-Aminobenzoic Acid/Tetrahydrofolate Biosynthesis Pathway. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2004, 43, 2574–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

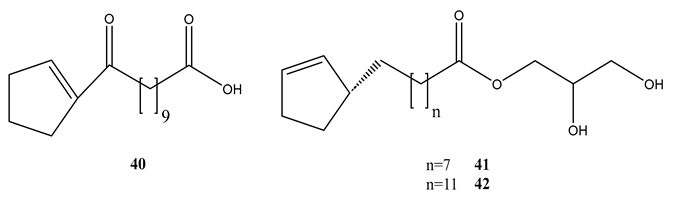

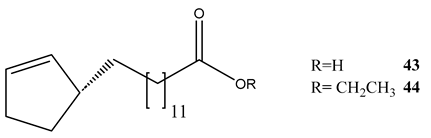

- Wang, J.-F.; Dai, H.-Q.; Wei, Y.-L.; Zhu, H.-J.; Yan, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-H.; Long, C.-L.; Zhong, H.-M.; Zhang, L.-X.; Cheng, Y.-X. Antituberculosis Agents and an Inhibitor of the Para-Aminobenzoic Acid Biosynthetic Pathway from Hydnocarpus anthelminthica Seeds. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, A.; Sharma, U.; Singh, D.; Dobhal, M.P.; Singh, S. Anti-Mycobacterial Activity of Plumericin and Isoplumericin against MDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Case, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.-J.; Tan, G.T.; Van Hung, N.; Cuong, N.M.; Franzblau, S.G.; Soejarto, D.D.; Fong, H.H.; et al. Anti-Tuberculosis Constituents from the Stem Bark of Micromelum hirsutum. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uc-Cachón, A.H.; Borges-Argáez, R.; Said-Fernández, S.; Vargas-Villarreal, J.; González-Salazar, F.; Méndez-González, M.; Cáceres-Farfán, M.; Molina-Salinas, G.M. Naphthoquinones Isolated from Diospyros anisandra Exhibit Potent Activity against Pan-Resistant First-Line Drugs Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strains. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 27, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, S.; Shaw, R.; Patra, M.M.; Calcuttawala, F.; Mukherjee, N.; Das Gupta, S.K. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Thymidylate Synthase (ThyX) Is a Target for Plumbagin, a Natural Product with Antimycobacterial Activity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | MIC (µM) | Cytotoxicity (IC50 (µM, Vero) | |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | M. smegmatis | ||

| Hapalindole A (4) | <0.6 | 18.2 | 31.9 |

| Hapalindole I (5) | 2 | >100 | >100 |

| Hapalindole X (6) | 2.5 | 78.8 | 35.2 |

| Compound | MIC (µM) | Cytotoxicity (IC50, µM, Vero) | |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | M. smegmatis | ||

| Ambiguine C isonitrile (10) | 7.0 | 59.6 | 78.3 |

| Ambiguine M isonitrile (11) | 7.5 | 25.8 | 79.8 |

| Ambiguine E isonitrile (12) | 21 | 1.4 | 42.6 |

| Compound | MIC (µM) | |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | M. bovis BCG | |

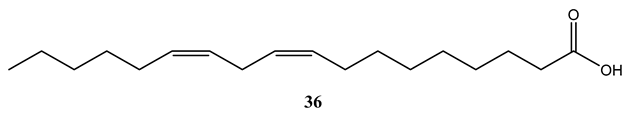

| Anthelminthicin A (40) | 5.54 | 13.8 |

| Anthelminthicin B (41) | 16.7 | 0.52 |

| Anthelminthicins C (42) | 4.38 | 11.2 |

| Chaulmoogric acid (43) | 9.82 | 2.36 |

| Ethyl chaulmoograte (44) | 16.8 | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).