1. Introduction

The skin is the most important organ in the human body and is composed of the epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous tissues, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, nerves, and muscles[

1]. The skin can enhance the function of its skin barrier by preventing the breakdown of lipids in the epidermis. Skin disorders can be caused by bacteria that alter the skin texture, fungi that develop on the skin, unknown germs, allergic reactions, or microorganisms that produce pigments[

2]. Prolonged skin conditions may potentially lead to tissue cancer in the human body [

3,

4,

5]. Skin disorders must be treated immediately to prevent future growth and spread. Currently, research is primarily focused on the use of imaging technology to assess the impact of different skin disorders on the skin.

Inadequate data and a focus on standardised procedures, such as dermoscopy (the inspection of the epidermis using skin surface microscopy), have made it difficult for medical practitioners to generalise the findings from prior work in dermatological computer-assisted grouping. Skin-related disorders can be quickly and precisely classified using computer-aided diagnostics to offer therapies based on patient complaints [

6]. This study provides a trustworthy approach for accurately diagnosing skin conditions by employing supervision techniques that reduce the cost of diagnosis. A grey-level co-occurrence matrix was used to track the development of ill growth. The accuracy of the diagnosis is crucial for a full examination of the anomaly, better therapy, and reduced drug costs.

Data-driven diagnosis is crucial because of the complexity of skin illnesses, lack of qualified dermatologists, and ineffective distribution of dermatologists. The identification of skin diseases is now easier and faster because of the development of lasers and photonics-based treatments for skin diseases. However, such diagnoses are expensive and scarce. Deep learning models are comparatively productive when used to perform classification processes using images and data. The precise determination of abnormalities and classification of disease categories from X-ray, MRI, CT, PET, and signal data, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) images, have become necessities in the field of medical diagnosis [

7]. Accurate illness categorisation will enable a more effective course of therapy. Deep learning models can solve complex problems by automatically identifying input data properties. They are also adaptable enough to evolve as the problem under consideration develops. Deep learning models can gather inferred data to locate and study features in unexposed data patterns, providing enormous efficiency even with simple computational models. Therefore, scientists have considered using deep learning models to classify skin infections based on images of the affected area.

The primary goal of this study is to provide a state-of-the-art method for reliably classifying skin illnesses from input photos, specifically MobileNetV3with an LSTM component [

8,

9]. The MobileNetV3 model is computationally effective for use with portable computing devices and low-resolution images, and LSTM is efficient in handling gradient fading over iterations in neural networks, facilitating faster model training. The proposed methodology would aid in the efficient and unobtrusive diagnosis of diseases in patients with the least amount of work and expenditure.

1.2. Related Works

Skin diseases are recognised and categorised using various automated technologies. Epidermal diagnosis of these skin illnesses does not involve radiological imaging technologies, in contrast to most other diagnostic techniques. By using image processing techniques, such as image alteration, equalisation, enhancement, edge detection, and segmentation, the state can be ascertained based on standard images [

10,

11].

The most commonly used approaches for artificial neural networks detecting and diagnosing anomalies in radiological imaging data are artificial neural networks and convolutional neural networks (CNN) [

12,

13]. The CNN approach for identifying skin disorders has yielded promising results [

14]. Working with images captured using a smartphone or digital camera presents challenges because CNN models are neither scale-nor rotation-invariant. To achieve high model performance, both neural network approaches require enormous amounts of training data, which require substantial computational effort [

15]. Because neural network-based models are more abstract, they cannot be modified to meet specific requirements. Moreover, the number of trainable parameters in the ANN increases with improved image quality, requiring substantial training efforts to yield accurate results. The ANN model has problems because of the contraction and expansion of gradients. Data obtained by CNN do not accurately describe the size and magnitude of an object [

16,

17].

MobileNetV2 is a CNN model that has various advantages over previous CNN models, including lower computing costs, smaller network size, and interoperability with mobile devices [

18]. MobileNetV2 features were assigned a timestamp as they were stored in the LSTM network [

4]. When MobileNetV2 was paired with LSTM, the accuracy improved by up to 85.34 percent [

14,

16,

17,

19,

20,

21].

Histogram equalisation is a simple and effective method for enhancing images. The equalizing approach has never been employed in a video system since it has the ability to substantially modify the brightness of a picture in certain conditions; this is why the technology has never been implemented. This study proposes a unique histogram equalisation approach termed equal-area dualistic sub-image histogram equalisation. Deep Learning (DL) is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) discipline in which a computer program analyses raw data and automatically learns the discriminating characteristics required for finding hidden patterns in it. Over the past decade, this discipline has seen significant breakthroughs in the capacity of

DL-based algorithms can be used to analyse many forms of data, particularly images [

22] and natural language.

Table 1.

A review of prior research focusing on the application of machine and deep learning methods in the classification of skin diseases.

Table 1.

A review of prior research focusing on the application of machine and deep learning methods in the classification of skin diseases.

| Methodology |

Findings |

Drawbacks |

Ref No |

| Integrating the LSTM with the MobileNet V2 |

Biomarker-based features, eHealth security, user-friendly apps. |

The model’s precision is dramatically decreased to just below 80 percent |

[23] |

| Deep learning |

The performance of the model may be further enhanced by using the bidirectional LSTM. |

If weight optimizations were used to include information about the present state, the model would be more robust. |

[24] |

| Hybrid Deep CNN |

To deploy and evaluate the system in real-world IoT environments to assess its performance and scalability. |

The proposed system is more complex to implement and manage than traditional IDS systems. |

[25] |

| Transfer learning |

Can be further enhanced by ensembling different deep learning models |

Minimal dataset |

[10] |

| Machine learning |

Using metaheuristic algorithm to further improve classification rate. |

Limited generalization to diverse skin types and conditions due to potential bias in training data. |

[26] |

| Transfer learning |

In future, various skin diseases such as chickenpox, smallpox, lumpy skin disease etc., will be targeted. |

Only 4 pre-trained models are applied and small dataset. |

[4] |

| DKCNN |

Enhancing precision even more for particular categories of skin diseases such as melanoma, melanocytic nevi, and benign keratosis-like lesions |

Limited ability to handle highly diverse or rare skin lesion types due to the focus on lightweight and dynamic kernel-based architecture. |

[24] |

| Transfer learning |

Improving skin disease detection using advanced DCNNs and transfer learning. |

The limited size and data imbalance of publicly available skin lesion datasets. |

[27] |

| Squeeze algorithm |

To make it compatible with Jetson Nano and the Google Coral Board. |

The major limitation of the system is that specificity and sensitivity are still lower than accuracy. |

[28] |

| Computer-aided diagnosis |

Use of hybrid methodologies of CNNs with handcrafted feature extraction approaches |

Yields a high computational cost. |

[29] |

| Transfer Learning |

Refine preprocessing techniques to improve skin cancer classification. |

Comparing skin cancer classification studies is challenging due to varying datasets and class numbers. |

[30] |

| Deep Learning |

Test diverse deep-learning techniques and datasets to improve skin disorder classification. |

Lack of dimensionality reduction methods to select the best features among all extracted features |

[3] |

| Deep Learning |

Detailed evaluation of the proposed model for skin disease detection and classification in adversarial environments. |

The proposed approach demonstrated a high misclassification rate for the Malignant. |

[31] |

| Artificial Intelligence |

Explore AI’s ability to use non-visual metadata like medical history for improved dermatology diagnostics. |

Inadequate standardized dermatology datasets hinder AI-based diagnosis reliability and practicality. |

[12] |

| Model Fusion |

Develop a lightweight model for versatility and evaluate it using diverse skin disease benchmark datasets. |

Proposed model had high training resource demands and relatively slow training speed. |

[22] |

1.3. Dataset Description

The DermNet dataset offers an extensive collection of high-resolution images showcasing a diverse array of dermatological conditions, including melanoma, psoriasis, and dermatitis. Its inclusiveness, which features various skin tones, ages, and ethnic backgrounds, simplifies the training of machine learning algorithms. High-quality images support in-depth analysis and precise diagnostic model development, benefiting automated dermatological diagnosis and expanding our understanding of skin diseases.

The dataset comprised images of 23 different skin disorders. There are approximately 19,500 photos in total, of which 15,500 are divided into the training and test sets. The photos were in JPEG format and had three RGB channels. Although the resolutions vary from image to image and from category to category, this imagery is not often of very high resolution.The classifications include vascular tumors, melanoma, eczema, seborrheic keratoses, ringworm, bullous illness, poison ivy, and acne.

Table 2.

Dataset Description.

Table 2.

Dataset Description.

| Class Label |

Abbreviation |

Super-Class Name |

No. of Images |

No. of Sub-Classes |

| 0 |

ACROS |

Acne and Rosacea |

912 |

21 |

| 1 |

AKBCC |

Actinic Keratosis, Basal Cell Carcinoma, and other Malignant Lesions |

1437 |

60 |

| 2 |

ATO |

Atopic Dermatitis |

807 |

11 |

| 3 |

BUL |

Bullous Diseases |

561 |

12 |

| 4 |

CEL |

Cellulitis, Impetigo, and other Bacterial Infections |

361 |

25 |

| 5 |

ECZ |

Eczema Photos |

1950 |

47 |

| 6 |

WXA |

Exanthems and Drug Eruptions |

497 |

18 |

| 7 |

ALO |

Alopecia and other Hair Diseases |

195 |

23 |

| 8 |

HER |

Herpes, Genital Warts and other STIs |

554 |

15 |

| 9 |

PIG |

Pigmentation Disorder |

711 |

20 |

| 10 |

LUPUS |

Lupus and other Connective Tissue diseases |

517 |

20 |

| 11 |

MEL |

Melanoma and Melanocytic Nevi |

635 |

15 |

| 12 |

NAIL |

Nail Fungus and other Nail Disease |

1541 |

48 |

| 13 |

POI |

Poison Ivy and other Contact Dermatitis |

373 |

12 |

| 14 |

PSO |

Psoriasis Lichen Planus and related diseases |

2112 |

39 |

| 15 |

SCA |

Scabies Lyme Disease and other Infestations and Bites |

611 |

25 |

| 16 |

SEB |

Seborrheic Keratoses and other Benign Tumors |

2397 |

50 |

| 17 |

SYS |

Systemic Disease |

816 |

43 |

| 18 |

TIN |

Tinea Candidiasis and other Fungal Infections |

1871 |

19 |

| 19 |

URT |

Urticaria |

603 |

18 |

| 20 |

VASC |

Vascular Tumors |

569 |

17 |

| 21 |

VASCP |

Vascular Tumors, Mollusca Contagiosa and other |

1549 |

26 |

| Total |

|

|

21844 |

622 |

2. Materials and Methods

The current study used the integration of LSTM with MobileNetV3, along with an associated architectural diagram. In this configuration, MobileNetV3 was used to categorise different forms of skin diseases, and LSTM was used to enhance the model performance by keeping track of the context of the characteristics encountered in the earlier stages of image classification [

32].

2.1. The MobileNet Model Architecture Designed for Image Classification

The model MobileNetV3, based on a CNN, is frequently used to classify photographs. Adopting the MobileNet design has several advantages, chief among them being that the model requires far less computing effort than a conventional CNN model, making it suitable for use with PCs with low processing capacities [

33]. The MobileNet model is a reduced convolution layer structure that can be used to differentiate between minute details that depend on two customisable characteristics that efficiently flip between the parameter accuracy and latency [

34]. The advantage of the MobileNet strategy is that it reduces the number of networks required. The MobileNet architecture is equally successful, with only a few features, such as recognition. A depth-first design underpins MobileNet, and the main framework relies on several abstraction layers and appears to be a quantised setup that accurately assesses the complexity of typical problems. Point-wise complexity describes the difficulty of 1 × 1. In-depth platforms are constructed using in-depth structures, abstraction layers, and standard rectified linear units (ReLU) [

35].

In computer vision, the creation of embedded device models is a new field of deep learning research that was essentially launched with the release of MobileNet V1 in 2017 [

36]. Numerous significant advancements, including MNasNet, EffNet, ShuffleNet (V1 and V2), and CondenseNet, were the result of this. Approximately the middle of the last year, the second generation of MobileNet emerged. Presently, the latest version of MobileNet is MobileNetV3, the third edition.

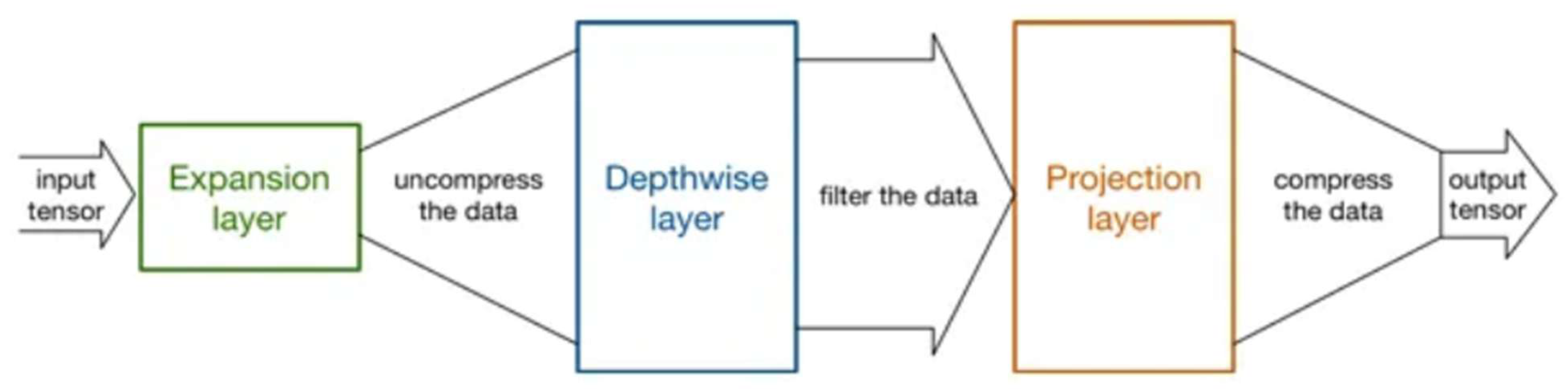

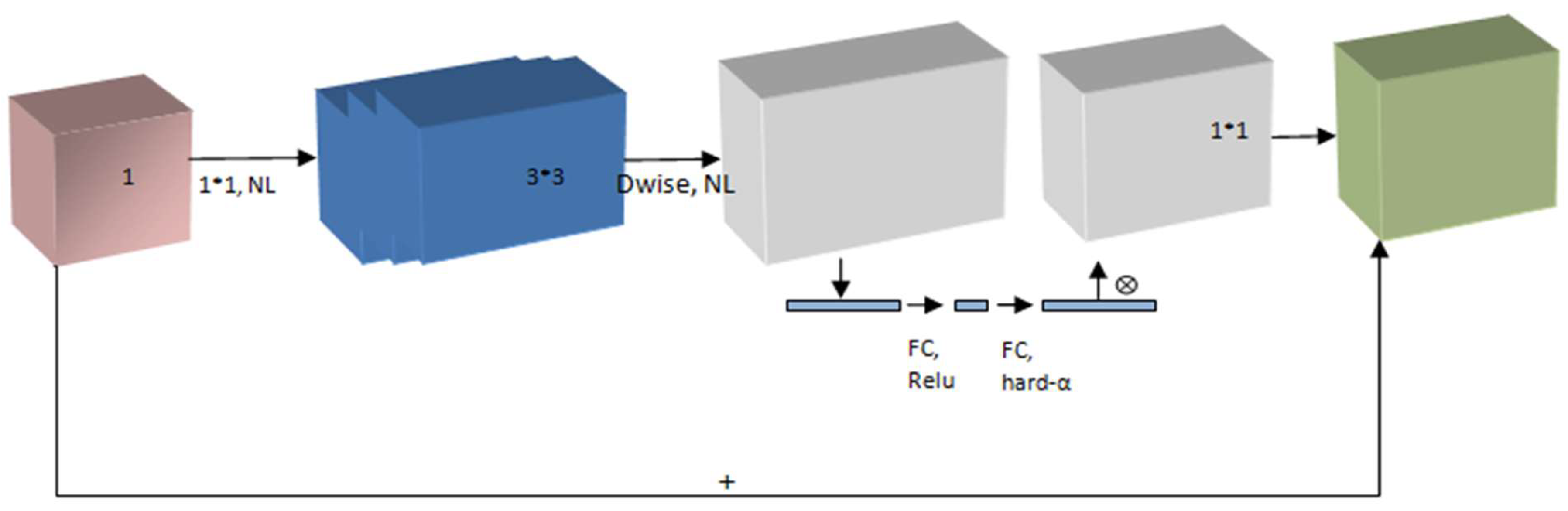

Figure 1.

The structure of MobileNetV3 Model.

Figure 1.

The structure of MobileNetV3 Model.

The resolution multiplier variable reduces both the dimensionality of the input image and the internal representation of every layer. The input variable is called a, and the output variable is called b. The feature vector map has dimensions Ms × Ms and the filter has dimensions Fs × Fs. The multiplier value was considered to be between 1 and n for the experimental study on the classification of dermatological illnesses [

37]. The circumstances determine the multiplier value. The symbol for the arbitrary resolution multiplier in Equation (1) uses the variable cost as a measure of the computational effort, which can be evaluated using V_cost.

The value Xe indicates the overall computing effort for the fundamental abstract layers of the design and can be evaluated using Equation (2):

The value of

was assumed to be 1. Equation (2) now becomes

The suggested method integrates depth-wise and point-wise convolutions that are bound by the depletion variable P, which is computed using Equation 4:

The two hyper-feature resolution multipliers and width multipliers enable context-dependent customisation of a suitably sized window for effective prediction [

23]. The recommended model requires an image with input dimensions of 224 × 224 × 3 pixels. The first two values (224, 224) represent the image height and width. These integers should always exceed 32. There were three input channels, as indicated by the third value.

As shown in

Figure 2, the MobileNet architectures operate on the idea of replacing complex convolutional layers, where each layer is composed of a convolutional layer of size 3 that buffers the input data and a convolutional layer of size 1 pointwise that incorporates these filtered parameters to generate a new component. The goal of the aforementioned strategy is to speed up and simplify the model compared with the traditional convolutional model.

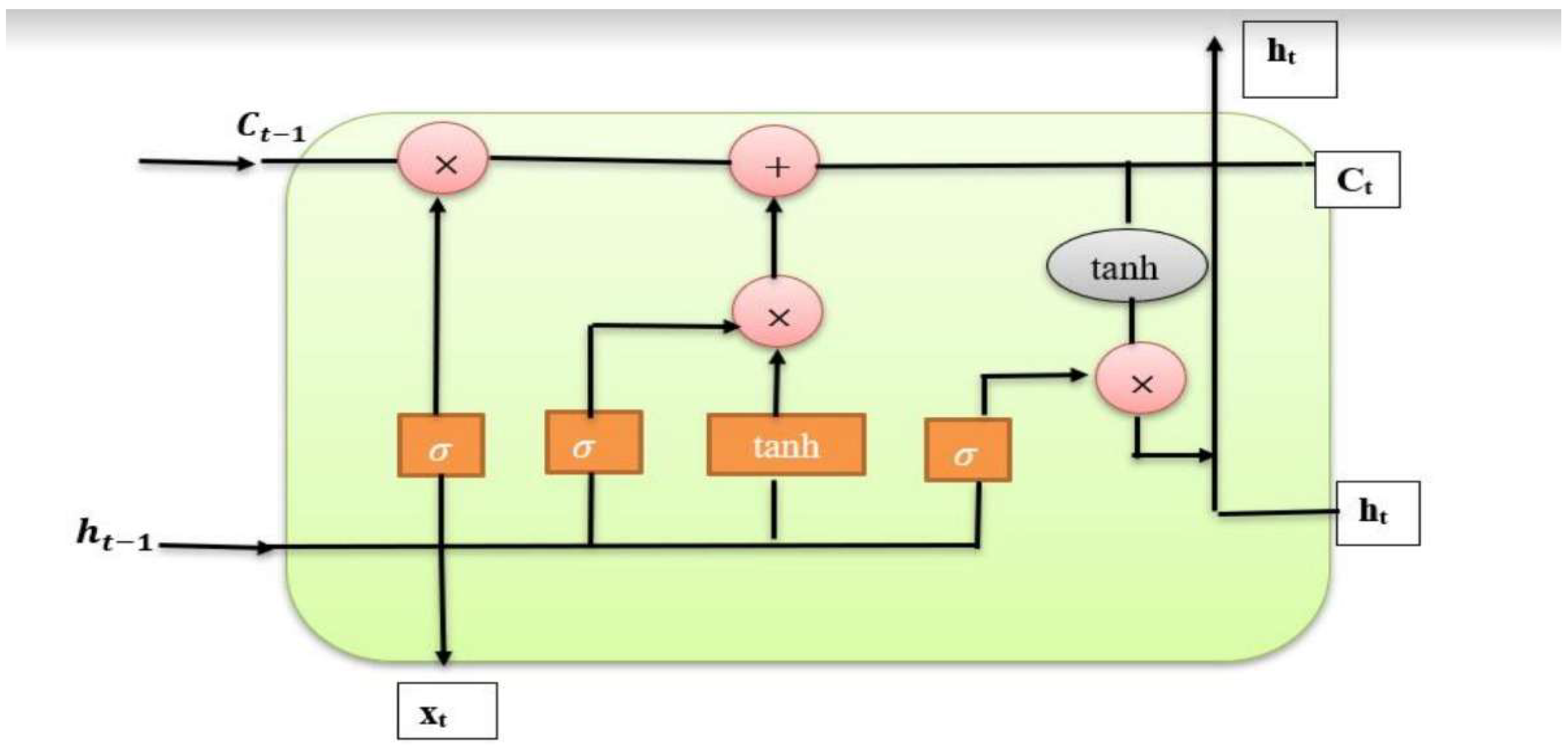

2.2. LSTM Model

An LSTM is a specific type of RNN designed to learn long-term dependency. Since Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997) originally presented LSTMs, several designs for these units have been created[

23,

38]. In brief, LSTM is a crucial component that is often employed in recurrent neural network architectures. It is particularly helpful in situations that require pattern estimation and excels at learning sequences. Memory blocks are supervised by memory cells, which in the LSTM structure are made up of an input gate, an output gate, a forget gate, and a link called a “window connection.” The abstract LSTM layer module is composed of the following components:

The computations within the LSTM module control the activation function of the persistent abstract LSTM memory. This module maintains the Pt state at time t while effectively managing memory. The input hidden state vector ht and the internal operations of the LSTM affect this state.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have emerged as a significant advancement in the domain of neural networks, particularly when used with sequential inputs. Owing to their capacity to recognise and analyse long-range relationships in sequential data, these networks have been widely used in several applications, including time-series forecasting, speech recognition, and natural language processing. The complicated workings of LSTM networks, along with their design, training procedures, and practical applications, were explored in depth in this study[

39].

Figure 3.

The design of the LSTM module.

Figure 3.

The design of the LSTM module.

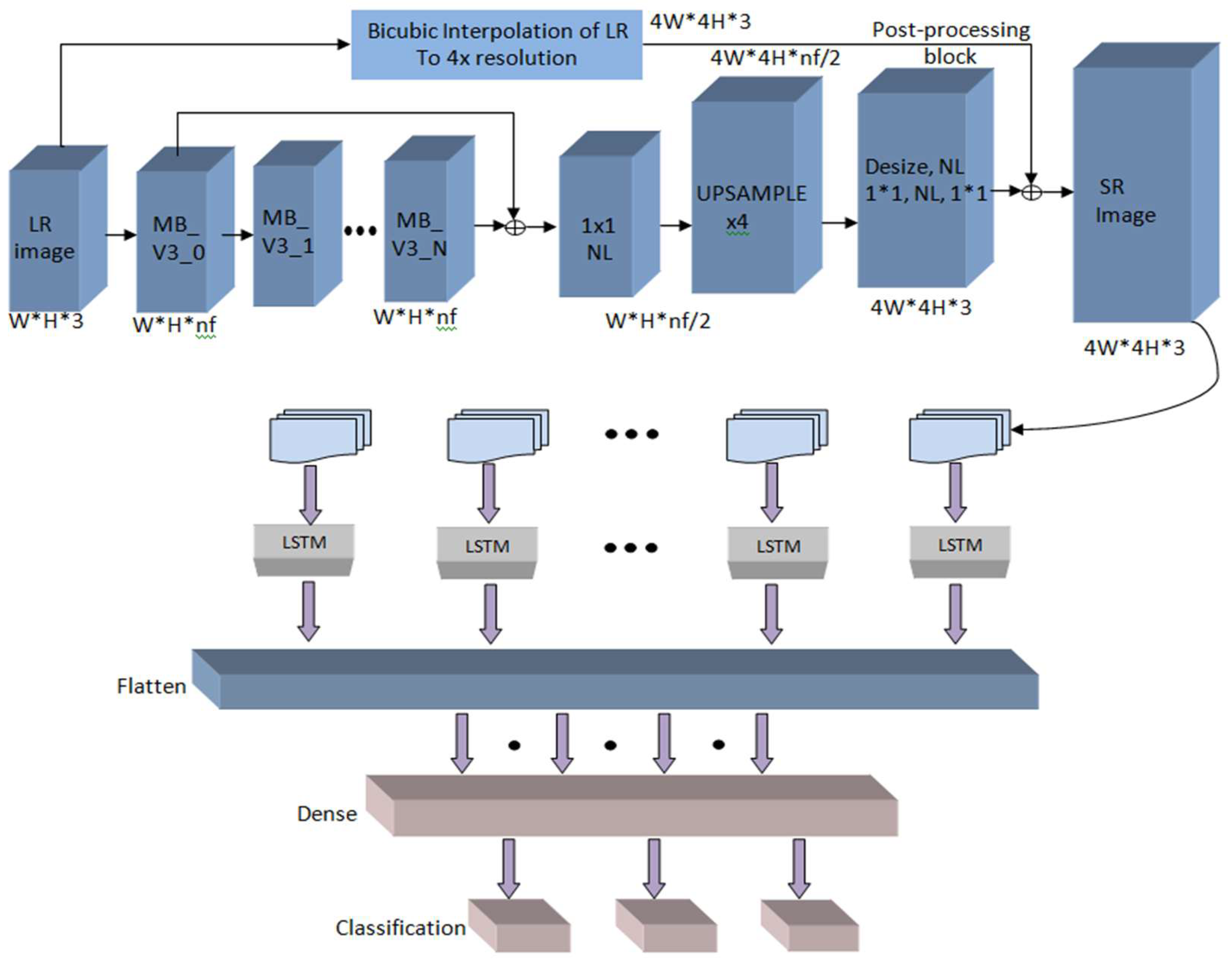

2.3. The Design of the Model That Combines MobileNet V3 and LSTM

Long short-term memory (LSTM) is a critical component of recurrent neural network topologies [

24]. It excels in learning sequences and is especially valuable for pattern estimation. Memory blocks are supervised by memory cells, which in the LSTM structure consist of an input gate, an output gate, a forget gate, and a link known as a “window connection.” Together, these elements comprise an abstract LSTM layer module.

The activation function of the persistent abstract LSTM memory module is controlled by calculations performed across the LSTM modules. This module maintains the Pt state at time t, while efficiently managing memory. This state is determined by both the hidden state vector (vt) of the input and the internal operations of the LSTM.

The variable ik is the input to the LSTM block at time ‘k’. The weights Wiα, Wiβ, Wif and Wic are are related to the input gate, output gate, forget gate, and cell stated gate, respectively. Whα, Whβ, and Wγf are the weights correlated with the hidden recurrent layer.

Figure 4.

The structure of the suggested model involving MobileNet V3 and LSTM.

Figure 4.

The structure of the suggested model involving MobileNet V3 and LSTM.

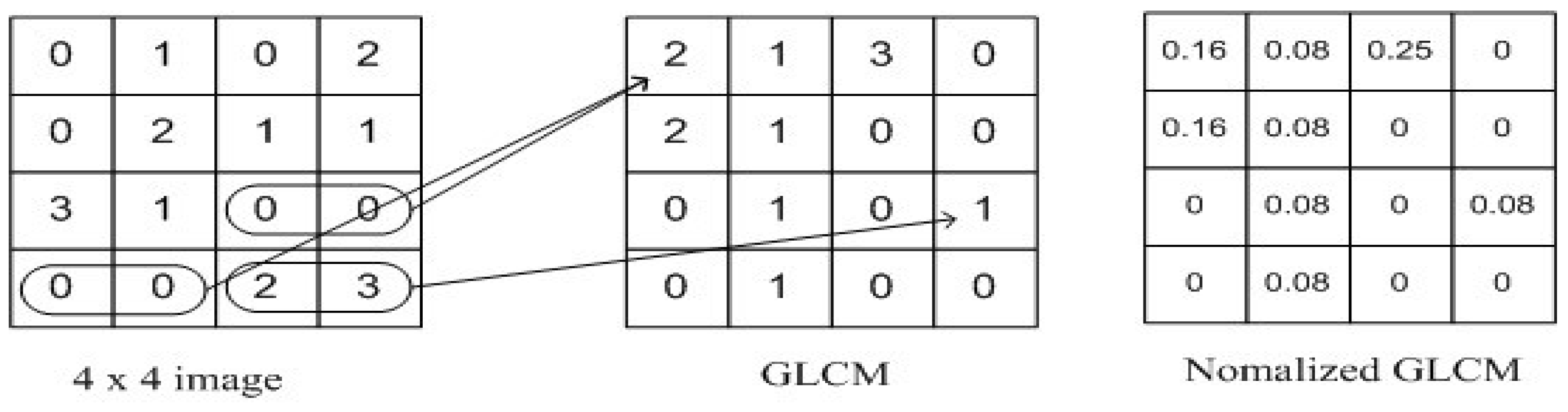

2.3.1. Grey Level Correlation Matrix

For texture analysis, the grey-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) was used. We simultaneously considered the reference pixel and the nearby pixel at the same time[

40]. Prior to computing the GLCM, we established a particular spatial relationship between the reference and neighbouring pixels. The definition of a neighbour may be, for example, one pixel to the right of the current pixel, three pixels above, or two pixels diagonally (one of NE, NW, SE, or SW) from the reference. As soon as a spatial relationship was established, we generated a GLCM of size (Range of Intensities × Range of Intensities) with all parameters set to 0. A 256x256 GLCM, for example, will be included in an 8-bit single-channel image. Next, we raise that matrix cell for each pair of intensities we find for the designated spatial link as we proceed through the image.

Figure 5.

Grey Level Correlation Matrix.

Figure 5.

Grey Level Correlation Matrix.

2.3.2. Gray Level Co-Occurrence Matrix

The Grey-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) method, coupled with the iterative sequence of the localized intensity coefficient, serves as a technique for extracting texture attributes. By analysing the distribution of intensity levels within a defined window, the GLCM captures the spatial distribution structure of the pixel colour and intensity. The primary objective of GLCM is to tabulate the intensity histogram to observe variations in pixel intensity values across an image. Equation (10) plays a crucial role in establishing the relationship between the reference and neighbouring pixels within the GLCM model. Here, the variable

represents the occurrence matrix with dimensions m × m, where m corresponds to the number of gray levels in the image.

The variable

in Equation (10) represents the histogram of the intensity value (i, j) at dimension m of the image. Equation (11) normalises the constituent parts of the occurrence matrix.

The normalisation of the matrix components rescales their dimensions to fall within the range of 0 to 1, which can be further adjusted based on probability considerations. Equation (12) offers a method to calculate both the number of elements and dimensions of the feature vector, denoted by the variable (l, m).

The GLCM technique was used to approximate the progression of disease development based on the gathered texture-based information. This model evaluates skin condition using the GLCM method.

3. Results and Discussion

The results and analysis of the recommended approach for diagnosing skin conditions are covered in more detail in this section. We evaluated the effectiveness of our technique by combining MobileNet V3 with LSTM, considering variables such as training, accuracy, and validation loss. As shown below, the effectiveness of our method is contrasted with that of other existing models in terms of Specificity, Sensitivity, Accuracy, and Jaccard Similarity Index (JSI).

3.1. Performance Evaluation of the Approach

The DermNet dataset, which is briefly explained in

Section 3, was used to apply the suggested approach. The frequency with which the proposed model accurately categorises skin ailments is determined by the recommended MobileNet V3 model, the implementation results of the LSTM model, and statistical analysis utilising numerous performance evolution indicators, including but not limited to accuracy metrics.

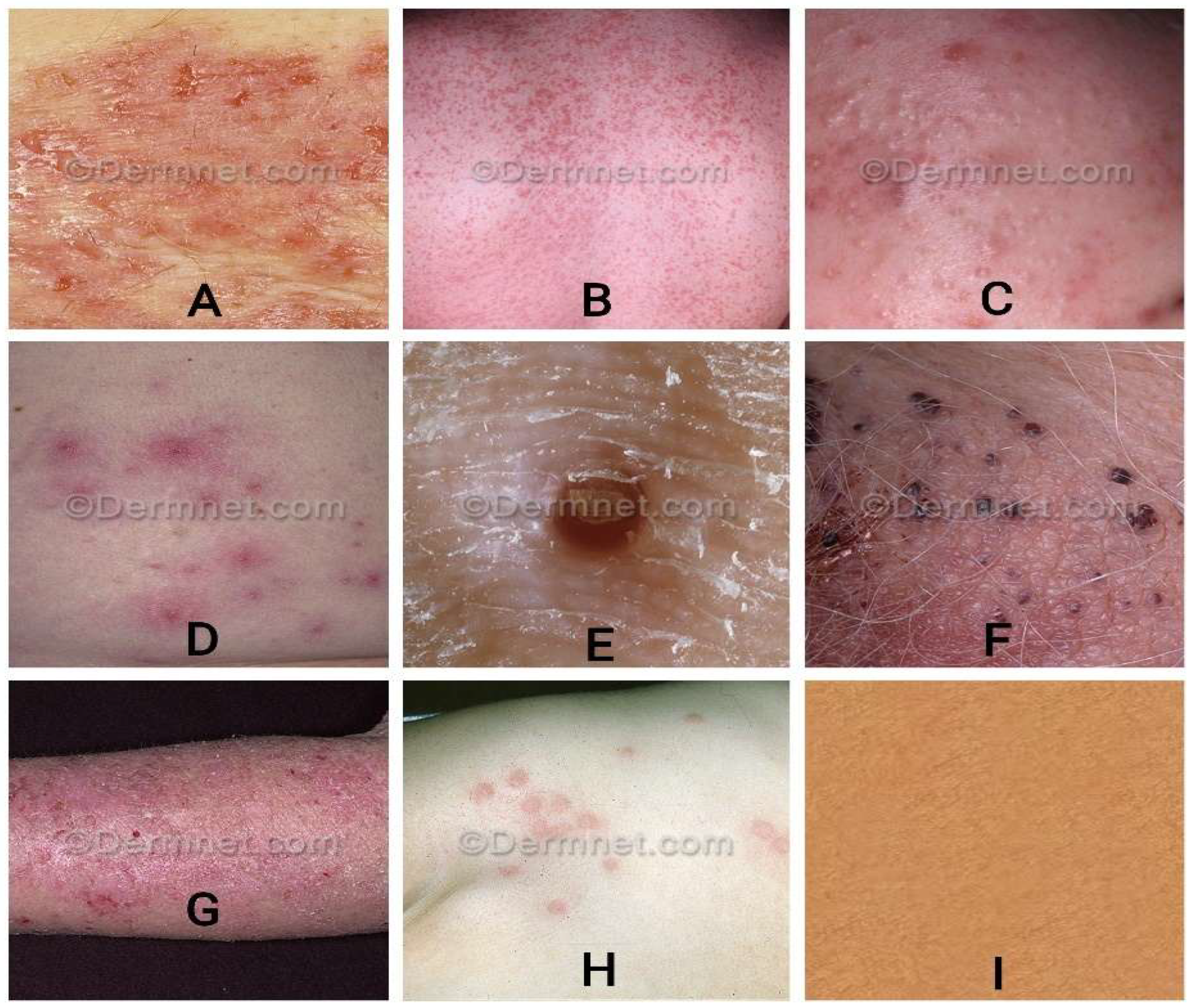

Figure 6.

Images of various image classes from the DermNet dataset. Images of various diseases are as follows: (A) bullous, (B) exanthem, (C) Skin Acne, (D) Cellulitis Impetigo,(E) molluscum, (F) vascular, (G) eczema, (H) scabies, and (I) normal skin.

Figure 6.

Images of various image classes from the DermNet dataset. Images of various diseases are as follows: (A) bullous, (B) exanthem, (C) Skin Acne, (D) Cellulitis Impetigo,(E) molluscum, (F) vascular, (G) eczema, (H) scabies, and (I) normal skin.

Table 3.

Hyper parameters configuration.

Table 3.

Hyper parameters configuration.

| MODEL |

Torch vision, MobileNet V3 |

| BASE LEARNING RATE |

0.1 |

| LEARNING RATE-POLICY |

Step-wise |

| WIEGHT DECAY |

0.0001 |

| CYCLIC LENGTH |

10 |

| PCT-START |

0.9 |

| MOMENTUM |

0.95 |

| BATCH SIZE |

50 |

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix for Different Classes of Images and its Accuracy.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix for Different Classes of Images and its Accuracy.

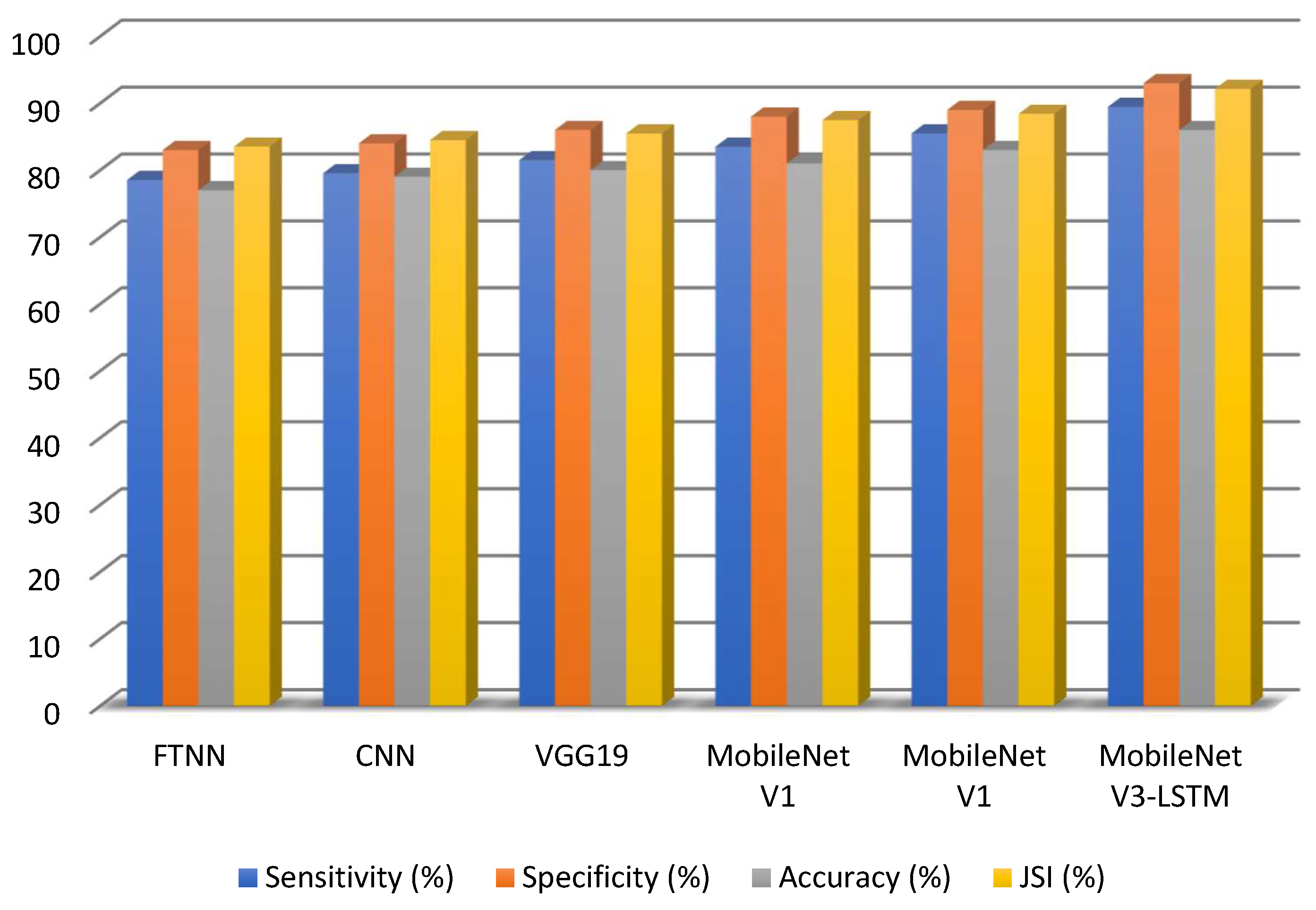

3.2. Past Study Analogy

The approach’s performance is compared to that of a Fine-Tuned Neural Network (FTNN), a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a VGC model, and several MobileNet models.

To evaluate the model’s performance, experiments were performed on a supplementary computer with repeated executions of the model. The ratings are based on how frequently the proposed model correctly categorises the True Positive skin disease and correctly identifies that the image is not of that specific skin category as the True Negative. The number of times the proposed model correctly detects the condition is sometimes addressed as a False Positive. The assumed False Negative is the number of times the recommended model erroneously evaluated the skin ailment.

The recommended model was evaluated for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy using metrics such as True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN). The Jaccard Similarity Index, Specificity, Sensitivity, and Accuracy were examined. The symbols for specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and the Jaccard Similarity Index are represented as Sn, Sp, A, and Ji, respectively.

The equations represent the metrics respectively,

The table shows how well our recommended technique performs in terms of JSI, Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy compared to other pertinent approaches.

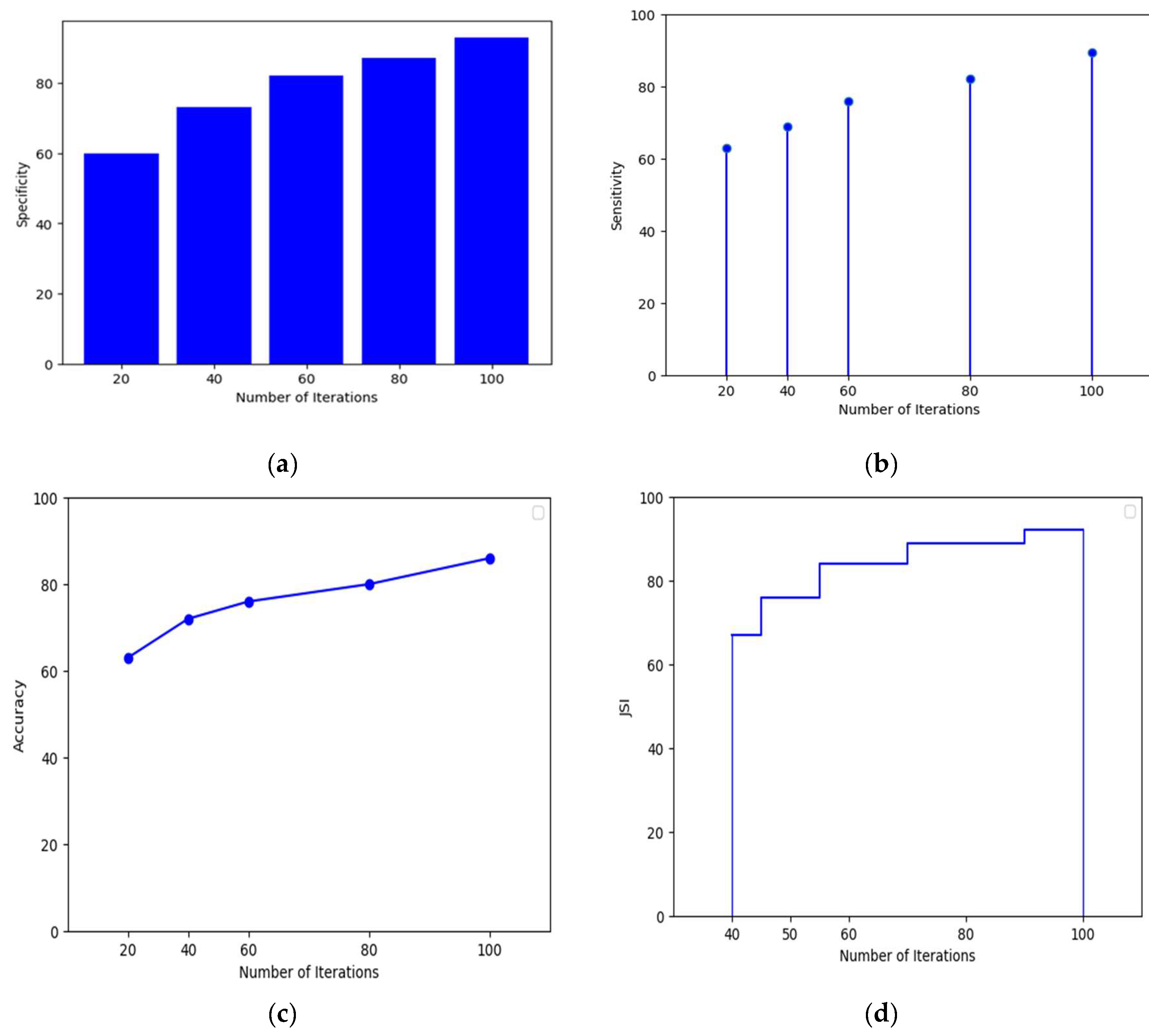

Figure 8.

(a) shows the Specificity of MobileNetV3-LSTM with respect to total number of iterations (b) illustrates the Sensitivity of MobileNetV3-LSTM with respect to number of iterations. (c) shows the MobileNetV3-LSTM’s accuracy in terms of iterations. (d) showcases the JSI of MobileNetV3-LSTM in terms of iterations.

Figure 8.

(a) shows the Specificity of MobileNetV3-LSTM with respect to total number of iterations (b) illustrates the Sensitivity of MobileNetV3-LSTM with respect to number of iterations. (c) shows the MobileNetV3-LSTM’s accuracy in terms of iterations. (d) showcases the JSI of MobileNetV3-LSTM in terms of iterations.

Table 4.

The evaluation criteria used to measure the effectiveness of different methods.

Table 4.

The evaluation criteria used to measure the effectiveness of different methods.

| Algorithms |

Sensitivity(%) |

Specificity(%) |

Accuracy(%) |

JSI(%) |

| MobileNet V3-LSTM |

89.46 |

93.00 |

86.00 |

92.14 |

| FTNN |

78.52 |

83.00 |

77.00 |

83.51 |

| CNN |

79.54 |

84.00 |

79.00 |

84.49 |

| VGG19 |

81.49 |

86.00 |

80.00 |

85.48 |

| MobileNet V1 |

83.49 |

88.00 |

81.00 |

87.46 |

| MobileNet V2 |

85.49 |

89.00 |

83.00 |

88.41 |

The Results Achieved by Comparing Existing Models with MobileNetV3-LSTM illustrates in

Figure 9. The performance of the proposed model was compared with that of several approaches, including the Lesion Index Calculation Unit (LICU) approach, Fuzzy Support Vector Machine with Probabilistic Boosting for Segmentation, the Compact Deep Neural Network, the SegNet model, U-Net model, Decision Tree and Random Forest approaches.

Table 5.

The progress of the disease’s growth of different methods.

Table 5.

The progress of the disease’s growth of different methods.

| Algorithms |

Sensitivity

(%) |

Specificity

(%) |

Accuracy

(%) |

| SegNet |

78.52 |

83.00 |

77.00 |

| U-Net |

79.54 |

84.00 |

79.00 |

| Yuan (CDNN) |

81.49 |

86.00 |

80.00 |

| MobileNet V3-LSTM |

89.46 |

93.00 |

86.00 |

Figure 10 shows the results obtained by comparing existing models with MobileNetV3-LSTM for monitoring the progression of disease growth.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we present MobileNet V3-LSTM, a unique technique for automated skin disease classification that combines MobileNet V3 and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. This novel solution uses the computational efficiency of MobileNet V3 for lightweight computing devices and LSTM’s sequence modelling capabilities of LSTM to extract critical contextual information from picture characteristics.

The application of the grey-level co-occurrence matrix, which enabled us to monitor the progression of skin conditions, was one of the key advancements of our method. This matrix provides vital insights into the progression of skin disorders, considerably improving diagnostic accuracy and speed. By including this matrix in our model, we not only increased its capacity to diagnose and categorise skin illnesses but also opened the door for more complete disease knowledge.

MobileNet V3-LSTM outperformed other state-of-the-art models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNN) and very deep convolutional networks (VGG), according to our experimental results on the Dermnet dataset. The model’s remarkable sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and Jaccard Similarity Index (JSI) proved its utility in precisely classifying illnesses.

The invention of the MobileNet V3-LSTM method represents a major advancement in computer-assisted dermatological diagnosis, and we have created a reliable and effective approach for the automated classification of skin illnesses by combining deep learning, sequence modelling, and the grey-level co-occurrence matrix. This technology has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs by assisting medical practitioners in making early and accurate diagnoses. Our strategy acts as a stepping stone for the creation of more advanced and useful technologies in dermatology and other fields as we continue to improve in the fields of medical imaging and artificial intelligence.

5. Future Directions

Future studies on computerised skin disease classification should focus on integrating various data sources, creating real-time diagnostics for portable devices, enhancing model interpretability, and diversifying datasets for improved generalisation. Other crucial research topics include scalability, continuous learning, clinical validation and privacy-preserving AI. These initiatives show the potential for developing dermatology and other healthcare-related fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and J.C; methodology, H.K, J.C, N.R and R.P; software, H.K, J.C and N.R; validation, H.K, J.C and N.R; formal analysis, H.K, J.C, N.R and R.P; investigation, H.K, J.C, N.R and R.P; resources, H.K, A.V, J.C, N.R and R.P; data curation, H.K, A.V and J.C; writing—original draft preparation, H.K, A.V, J.C, N.R and R.P; writing—review and editing, H.K, A.V; visualization, H.K, A.V, J.C, N.R and R.P; supervision, A.V, N.R and R.P; project administration, A.V and N.R; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The third author, Harichandra Khalingarajah, is a recipient of the INTI International University Graduate Research Scholarship Scheme 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EffNet |

EfficientNet |

| FTNN |

Fine-Tuned Neural Network |

| GLCM |

Grey-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| JSI |

Jaccard Similarity Index |

| LICU |

Lesion Index Calculation Unit |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| MN |

MnasNet |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| SqueezeNet |

A smaller neural network architecture designed for efficient use |

| U-Net |

A type of convolutional neural network for image segmentation |

| V1/V2/V3 |

MobileNet Versions 1, 2, and 3 |

| VGG |

Visual Geometry Group |

References

- J. Salazar et al., “The Human Dermis as a Target of Nanoparticles for Treating Skin Conditions,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Pop and Z. Diaconeasa, “Recent Advances in Phenolic Metabolites and Skin Cancer,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 18, Art. no. 18, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Almuayqil, S. S. N. Almuayqil, S. Abd El-Ghany, and M. Elmogy, “Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Early Signs of Skin Diseases Using Multi Types Feature Fusion Based on a Hybrid Deep Learning Model,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 23, Art. no. 23, Jan. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Z. Khan and I. Ullah, “Efficient Technique for Monkeypox Skin Disease Classification with Clinical Data using Pre-Trained Models,” Journal of Innovative Image Processing, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 192–213, Jun. 2023.

- J. D. Strickley et al., “Immunity to commensal papillomaviruses protects against skin cancer,” Nature, vol. 575, no. 7783, pp. 519–522, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. G. Debelee, “Skin Lesion Classification and Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Systematic Review,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 19, Art. no. 19, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Mienye, T. G. D. Mienye, T. G. Swart, G. Obaido, M. Jordan, and P. Ilono, “Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Review,” Information, vol. 16, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, L. J. Hu, L. Shen, and G. Sun, “Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Jun. 2018, pp. 7132–7141. [CrossRef]

- W. Ai, “Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Framework for Bearings Based on a Hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU Network,” Scientific Innovation in Asia, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1–7, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Sadik, A. R. Sadik, A. Majumder, A. A. Biswas, B. Ahammad, and Md. M. Rahman, “An in-depth analysis of Convolutional Neural Network architectures with transfer learning for skin disease diagnosis,” Healthcare Analytics, vol. 3, p. 100143, Nov. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, M. M. Liu, M. Zhu, M. White, Y. Li, and D. Kalenichenko, “Looking Fast and Slow: Memory-Guided Mobile Video Object Detection,” Mar. 2019; 25, arXiv:arXiv:1903.10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. N. Bajwa et al., “Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Skin Diseases Using Deep Neural Networks,” Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ji, L. Z. Ji, L. Li, and H. Bi, “Deep Learning-Based Approximated Observation Sparse SAR Imaging via Complex-Valued Convolutional Neural Network,” Remote Sensing, vol. 16, no. 20, Art. no. 20, Jan. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Sandler, A. M. Sandler, A. Howard, M. Zhu, A. Zhmoginov, and L. -C. Chen, “MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Jun. 2018, pp. 4510–4520. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Rabano, M. K. S. L. Rabano, M. K. Cabatuan, E. Sybingco, E. P. Dadios, and E. J. Calilung, “Common Garbage Classification Using MobileNet,” in 2018 IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology,Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Dec. 2018, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- M. A. M. Almeida and I. A. X. Santos, “Classification Models for Skin Tumor Detection Using Texture Analysis in Medical Images,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 6, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Anand, S. V. Anand, S. Gupta, S. R. Nayak, D. Koundal, D. Prakash, and K. D. Verma, “An automated deep learning models for classification of skin disease using Dermoscopy images: a comprehensive study,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 81, no. 26, pp. 37379–37401, Nov. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Brosch, L. Y. W. T. Brosch, L. Y. W. Tang, Y. Yoo, D. K. B. Li, A. Traboulsee, and R. Tam, “Deep 3D Convolutional Encoder Networks With Shortcuts for Multiscale Feature Integration Applied to Multiple Sclerosis Lesion Segmentation,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 20 May 1229; 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Alphonse and M. S. Starvin, “A novel maximum and minimum response-based Gabor (MMRG) feature extraction method for facial expression recognition,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 78, no. 16, pp. 23369–23397, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J. Wang, Y. Duan, B. Fu, J.-R. Kang, and Y. Shi, “MobileNet Based Apple Leaf Diseases Identification,” Mobile Netw Appl, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 172–180, Feb. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Rigel, R. J. S. Rigel, R. J. Friedman, A. W. Kopf, and D. Polsky, “ABCDE - An evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma,” JAMA dermatology, vol. 141, no. 8, pp. 1032–1034, Aug. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Wei et al., “A Skin Disease Classification Model Based on DenseNet and ConvNeXt Fusion,” Electronics, vol. 12, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Srinivasu, J. G. P. N. Srinivasu, J. G. SivaSai, M. F. Ijaz, A. K. Bhoi, W. Kim, and J. J. Kang, “Classification of Skin Disease Using Deep Learning Neural Networks with MobileNet V2 and LSTM,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Jan. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. R. Kshirsagar, H. P. R. Kshirsagar, H. Manoharan, S. Shitharth, A. M. Alshareef, N. Albishry, and P. K. Balachandran, “Deep Learning Approaches for Prognosis of Automated Skin Disease,” Life (Basel), vol. 12, no. 3, p. 426, Mar. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Hameed, A. M. N. Hameed, A. M. Shabut, and M. A. Hossain, “Multi-Class Skin Diseases Classification Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Support Vector Machine,” in 2018 12th International Conference on Software, Knowledge, Information Management & Applications (SKIMA), Dec. 2018, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- C.-Y. Zhu et al., “A Deep Learning Based Framework for Diagnosing Multiple Skin Diseases in a Clinical Environment,” Front. Med., vol. 8, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Arjun and K. S. Kumar, “A combined approach of VGG 16 and LSTM transfer learning technique for skin melanoma classification,” International journal of health sciences, vol. 6, no. S1, Art. no. S1, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Shinde et al., “Squeeze-MNet: Precise Skin Cancer Detection Model for Low Computing IoT Devices Using Transfer Learning,” Cancers, vol. 15, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. O. Molina-Molina, S. E. O. Molina-Molina, S. Solorza-Calderón, and J. Álvarez-Borrego, “Classification of Dermoscopy Skin Lesion Color-Images Using Fractal-Deep Learning Features,” Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 17, Art. no. 17, Jan. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Arshed, S. M. A. Arshed, S. Mumtaz, M. Ibrahim, S. Ahmed, M. Tahir, and M. Shafi, “Multi-Class Skin Cancer Classification Using Vision Transformer Networks and Convolutional Neural Network-Based Pre-Trained Models,” Information, vol. 14, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Ravi, “Attention Cost-Sensitive Deep Learning-Based Approach for Skin Cancer Detection and Classification,” Cancers, vol. 14, no. 23, Art. no. 23, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Vardasca, J. G. R. Vardasca, J. G. Mendes, and C. Magalhaes, “Skin Cancer Image Classification Using Artificial Intelligence Strategies: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 10, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Nie, M. Z. Nie, M. Xu, Z. Wang, X. Lu, and W. Song, “A Review of Application of Deep Learning in Endoscopic Image Processing,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 10, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, J. Y. Yuan, J. Sun, and Q. Zhang, “An Enhanced Deep Learning Model for Effective Crop Pest and Disease Detection,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 10, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Mienye and T. G. Swart, “A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning: Architectures, Recent Advances, and Applications,” Information, vol. 15, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Wu, and Y. Iwahori, “Advances in Computer Vision and Deep Learning and Its Applications,” Electronics, vol. 14, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Jan. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Behara, E. K. Behara, E. Bhero, and J. T. Agee, “Skin Lesion Synthesis and Classification Using an Improved DCGAN Classifier,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 16, Art. no. 16, Jan. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, “Long Short-Term Memory,” Neural Computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735–1780, Nov. 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang and V. Chouvatut, “Video-Based Sign Language Recognition via ResNet and LSTM Network,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 10, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, X. X. Huang, X. Liu, and L. Zhang, “A Multichannel Gray Level Co-Occurrence Matrix for Multi/Hyperspectral Image Texture Representation,” Remote Sensing, vol. 6, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).