Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Leukemias and Their Diagnostic Process

3. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

3.2. Methodology

-

Q1: ("artificial intelligence" OR "AI" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning") AND ("histopathology" OR "digital pathology" OR "histological image" OR "microscopic image") AND ("diagnosis" OR "diagnostic support" OR "classification")Broad general query covering applications of artificial intelligence in histopathological and cytological image analysis in hematology, without limiting to specific leukemia types.

-

Q2: ("artificial intelligence" OR "AI" OR "deep learning" OR "machine learning") AND ("leukemia" OR "leukaemia" OR "AML" OR "ALL" OR "CML" OR "CLL") AND ("diagnosis" OR "diagnostic aid" OR "detection" OR "classification") AND ("histopathology" OR "cytology" OR "microscopic image" OR "blood smear" OR "bone marrow smear")A more specific query targeting the use of machine learning and deep learning methods in leukemia diagnostics based on microscopic images, particularly focusing on blood and bone marrow cell morphology.

-

Q3: ("convolutional neural network" OR "CNN" OR "deep learning") AND ("blood smear" OR "bone marrow smear" OR "cytological image" OR "histopathology") AND ("leukemia" OR "blood cancer" OR "hematological malignancy")Query focusing on AI applications in automatic classification and detection of hematological diseases, with an emphasis on computer-aided diagnostic systems.

-

Q4: ("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning") AND ("leukemia subtype" OR "ALL subtypes" OR "AML subtypes" OR "FAB classification" OR "immunophenotyping") AND ("classification" OR "differentiation" OR "subtype detection")Query focused on systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and review articles on the role of AI in leukemia diagnostics, capturing trends and current knowledge summaries.

-

Q5: ("machine learning" OR "deep learning") AND ("SVM" OR "support vector machine" OR "random forest" OR "CNN" OR "neural network") AND ("leukemia" OR "hematological malignancy") AND ("image analysis" OR "cell classification")Technical query covering innovative algorithms, neural network architectures (e.g., CNN), and explainable AI systems in morphological image analysis for hematologic diagnostics.

- Language: English

- Publication types: Articles, Reviews

- Topic: AI in histopathological/cytological diagnostics of leukemias

- 1.

-

From each publication set, we selected papers whose abstracts/titles contained at least one keyword from the:

- AI group (“artificial intelligence”, “ai”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “neural network”, “cnn”, “convolutional neural network”, “computer-aided diagnosis”, “automated diagnosis”, “intelligent system”)

- Morphological image analysis group (“histopathology”, “histopathological”, “cytology”, “cytological”, “microscopic image”, “blood smear”, “bone marrow”, “digital pathology”, “cell morphology”, “image analysis”)

- 2.

- From the publications passing the previous screening, we additionally selected only those where the abstracts/titles contained the word ”leukemia”.

- 3.

- Abstracts and titles of the selected publications were then analyzed, and those outside our thematic scope were excluded.

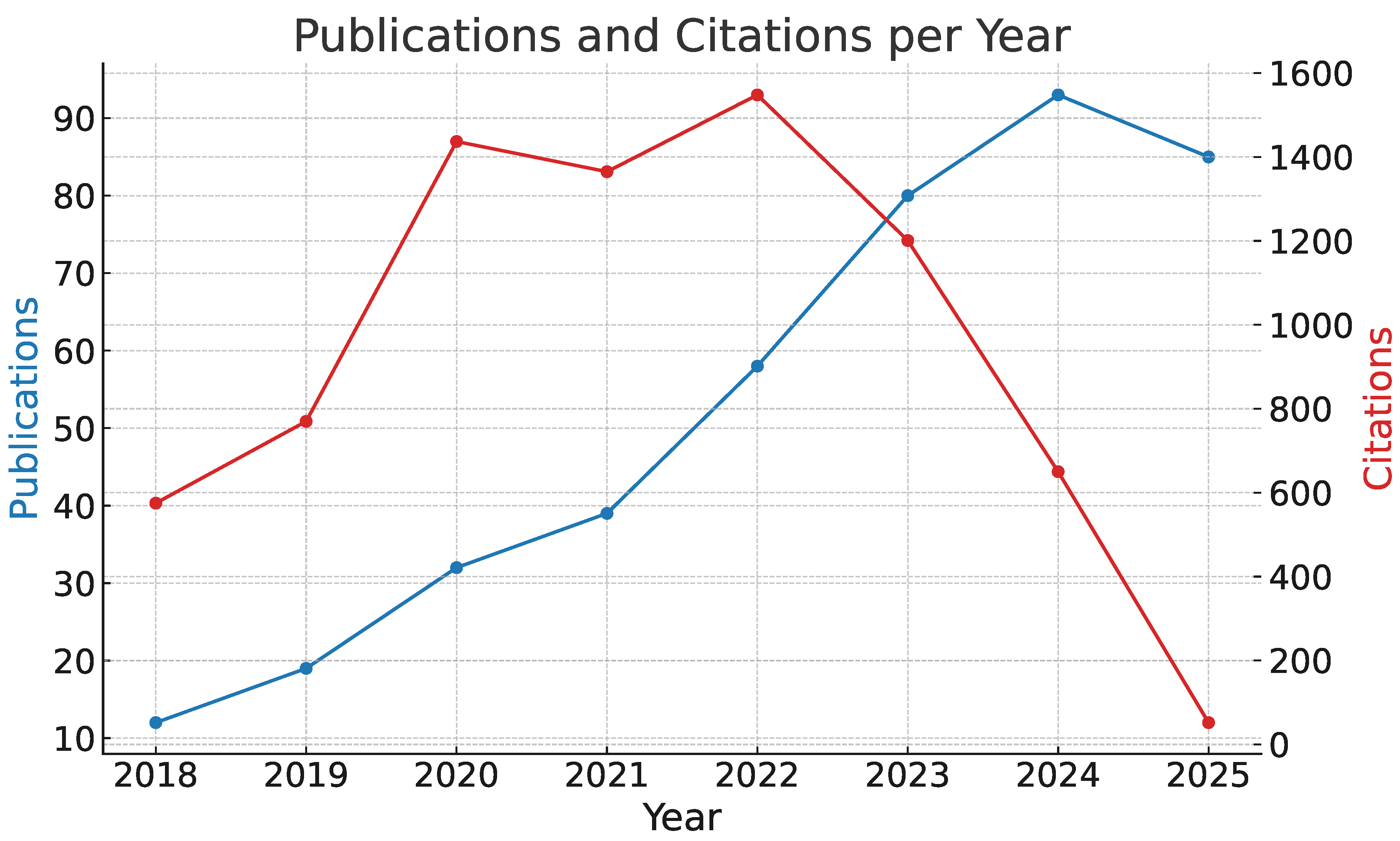

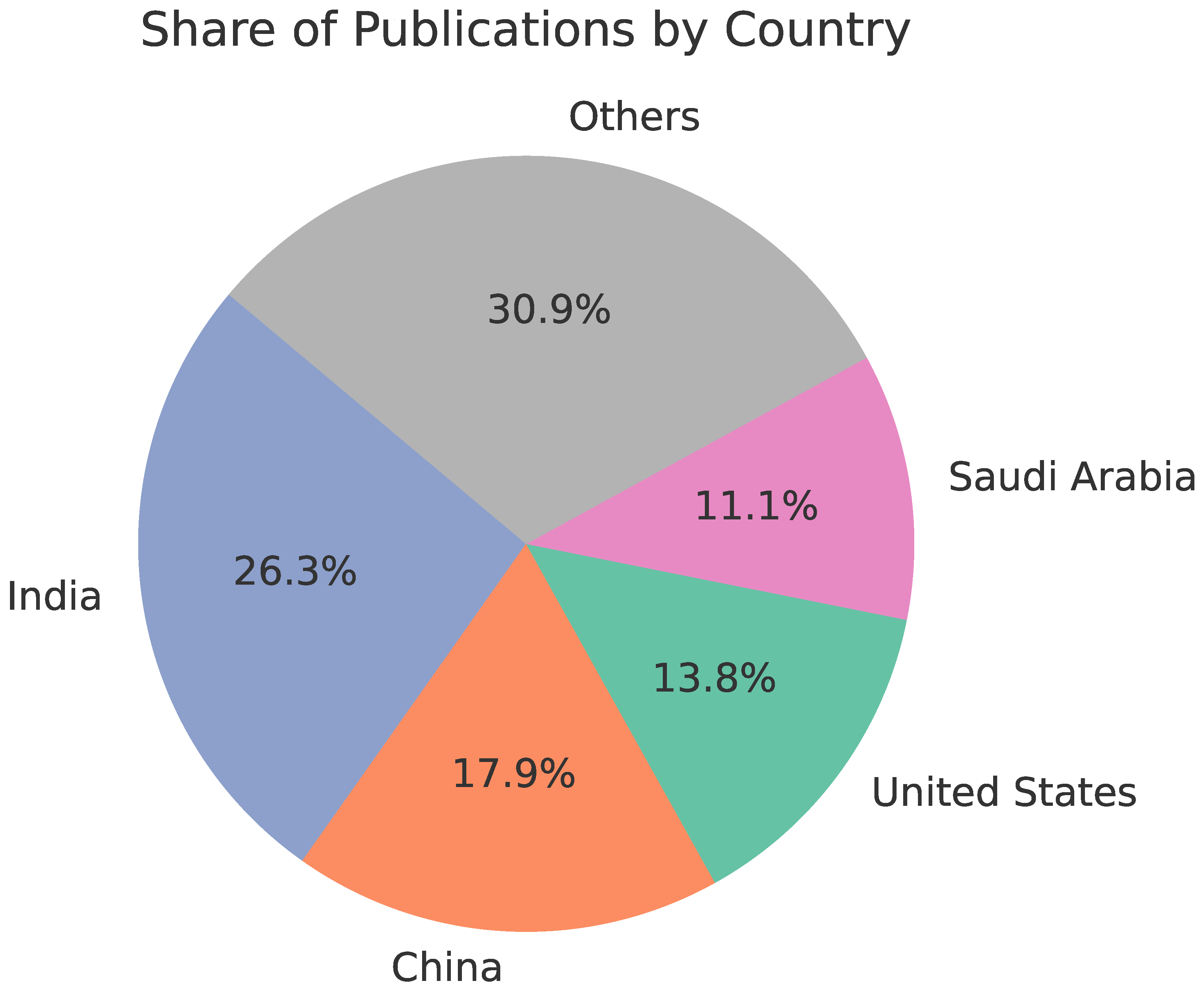

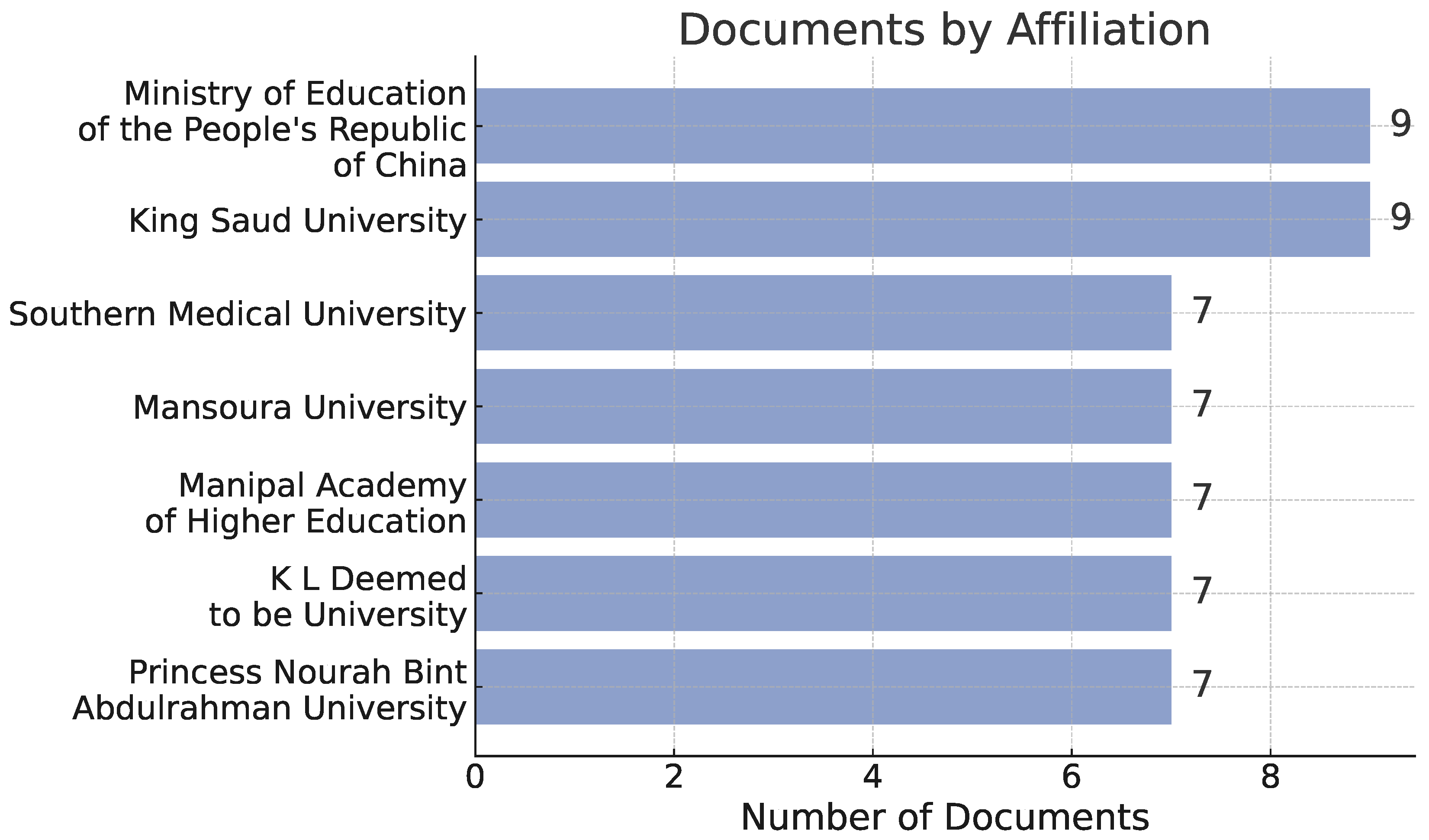

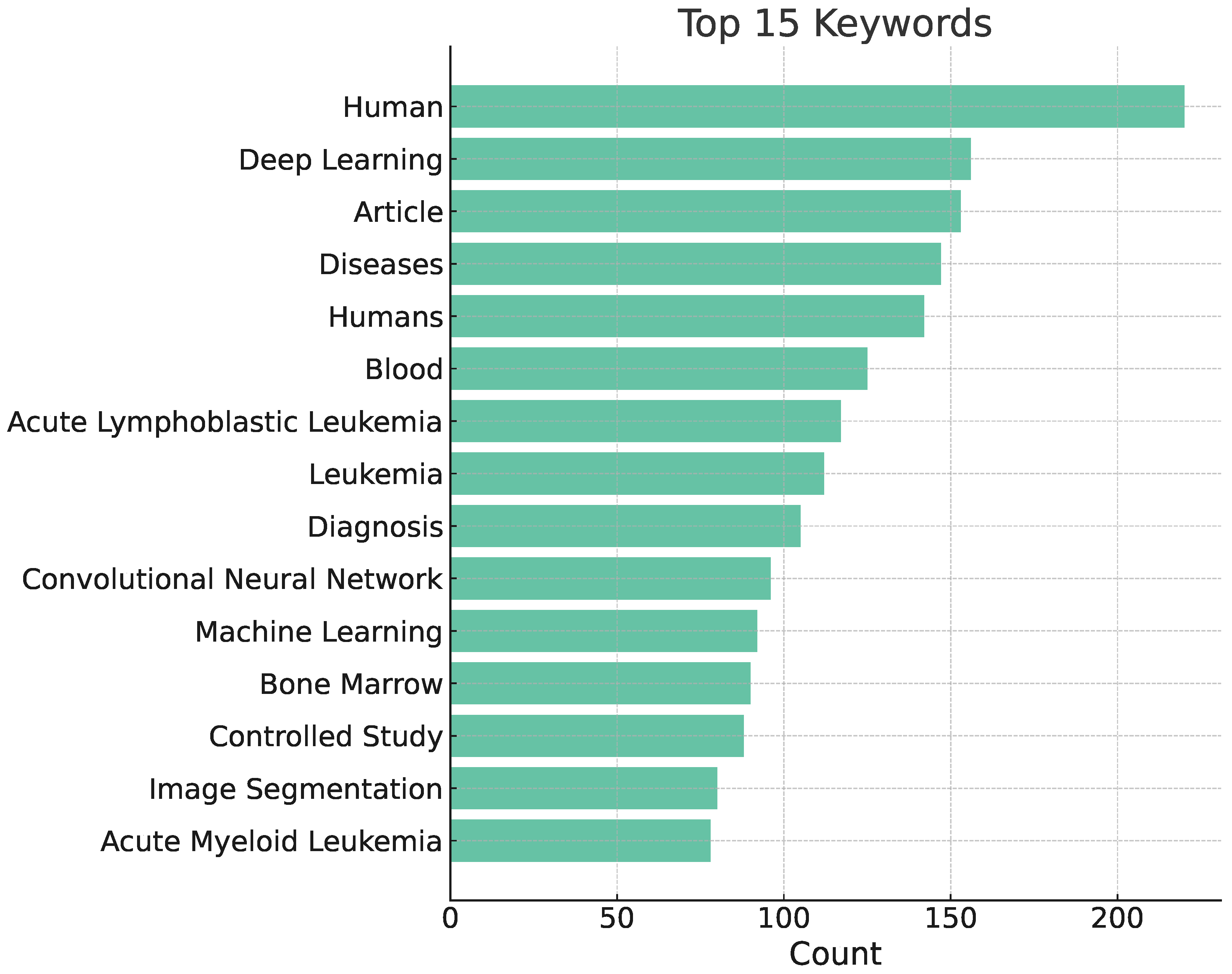

3.3. Results

- Q1: 46,690 publications retrieved from Scopus → 10,939 after the first selection stage → 336 after the second selection stage

- Q2: 22,418 publications retrieved from Scopus → 4,438 after the first selection stage → 381 after the second fselection stage

- Q3: 2,397 publications retrieved from Scopus → 825 after the first selection stage → 299 after the second selection stage

- Q4: 1,780 publications retrieved from Scopus → 286 after the first selection stage → 147 after the second selection stage

- Q5: 2,646 publications retrieved from Scopus → 820 after the first selection stage → 255 after the second selection stage

3.4. Limitations

3.5. Conclusions

4. Datasets

5. Image Processing Methods Used for Histopathological Diagnostics of Leukemias

-

Classical — staged or modular processing approach, whereby distinct phases can be identified:

- -

- preliminary processing (e.g., denoising, normalisation),

- -

- features extraction (e.g., segmantation, edge detection, Hough transform),

- -

- classification (e.g., SVM, random forest).

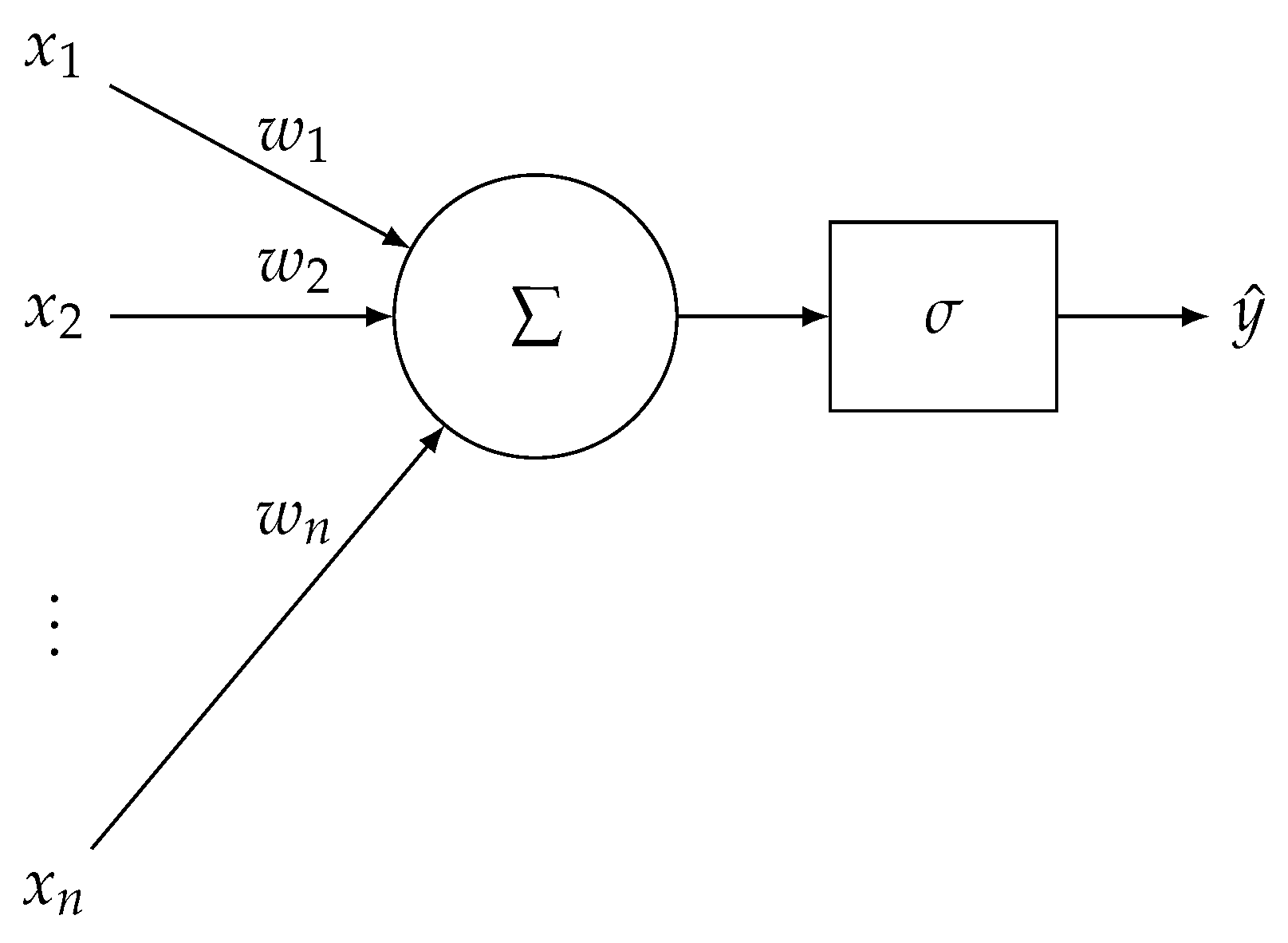

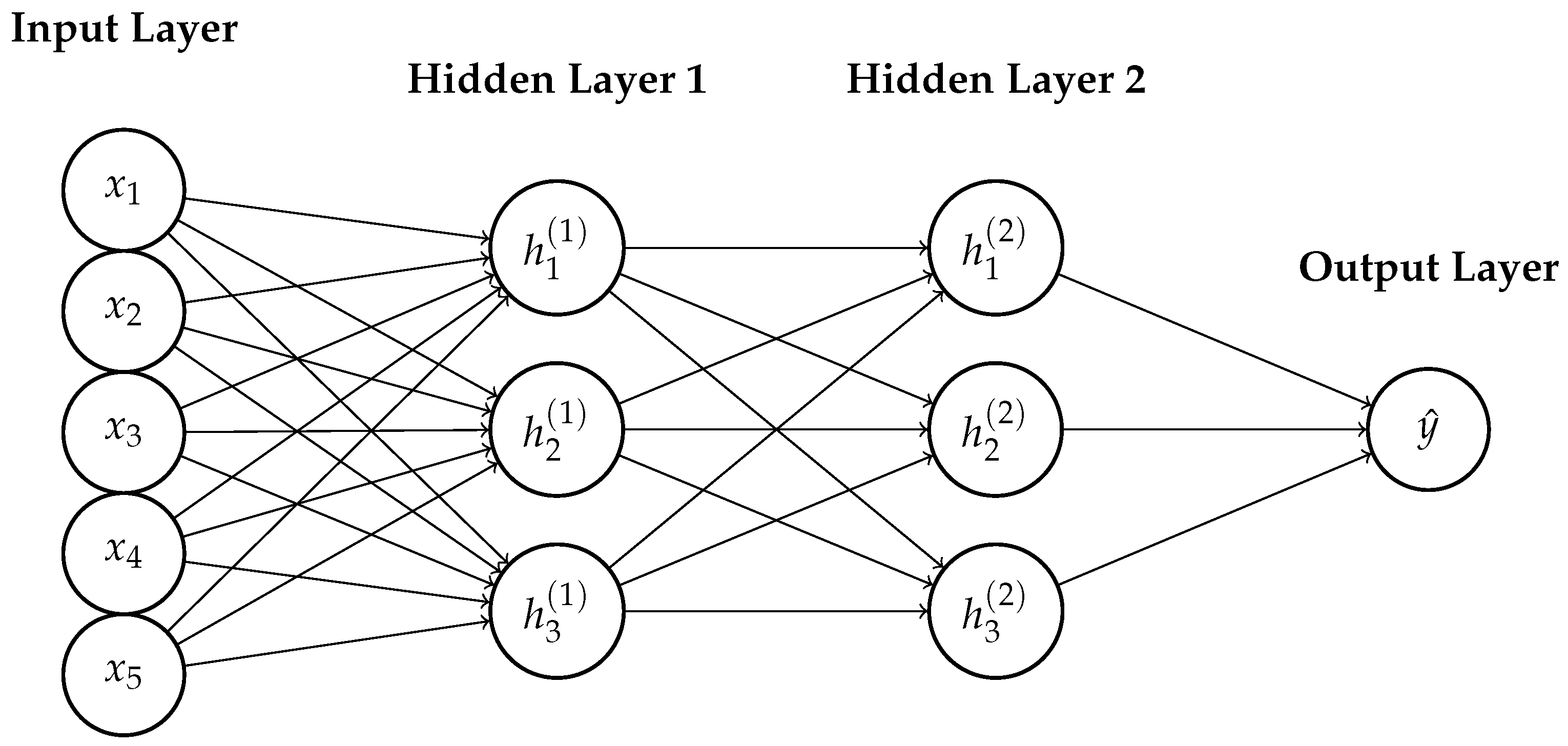

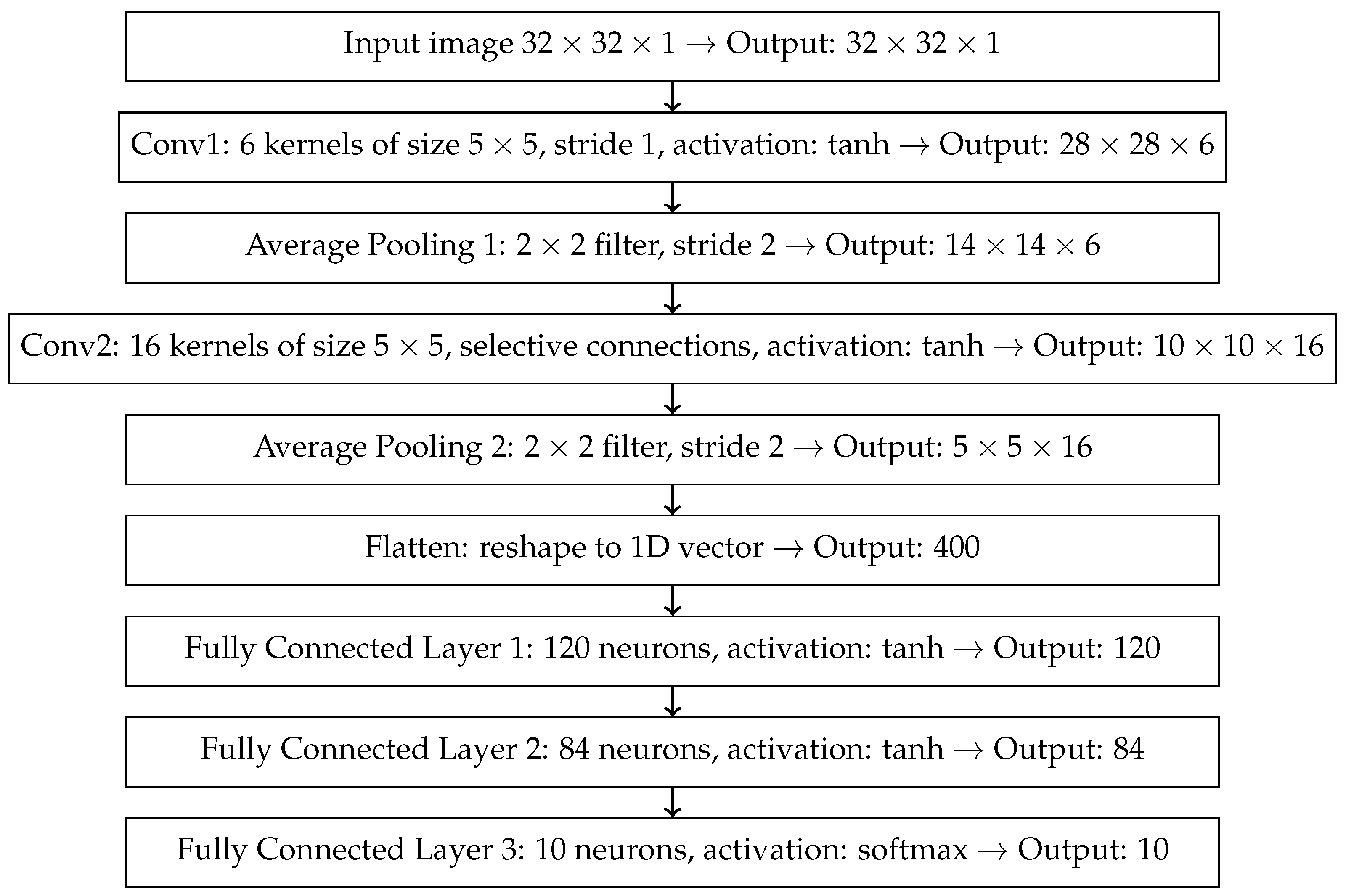

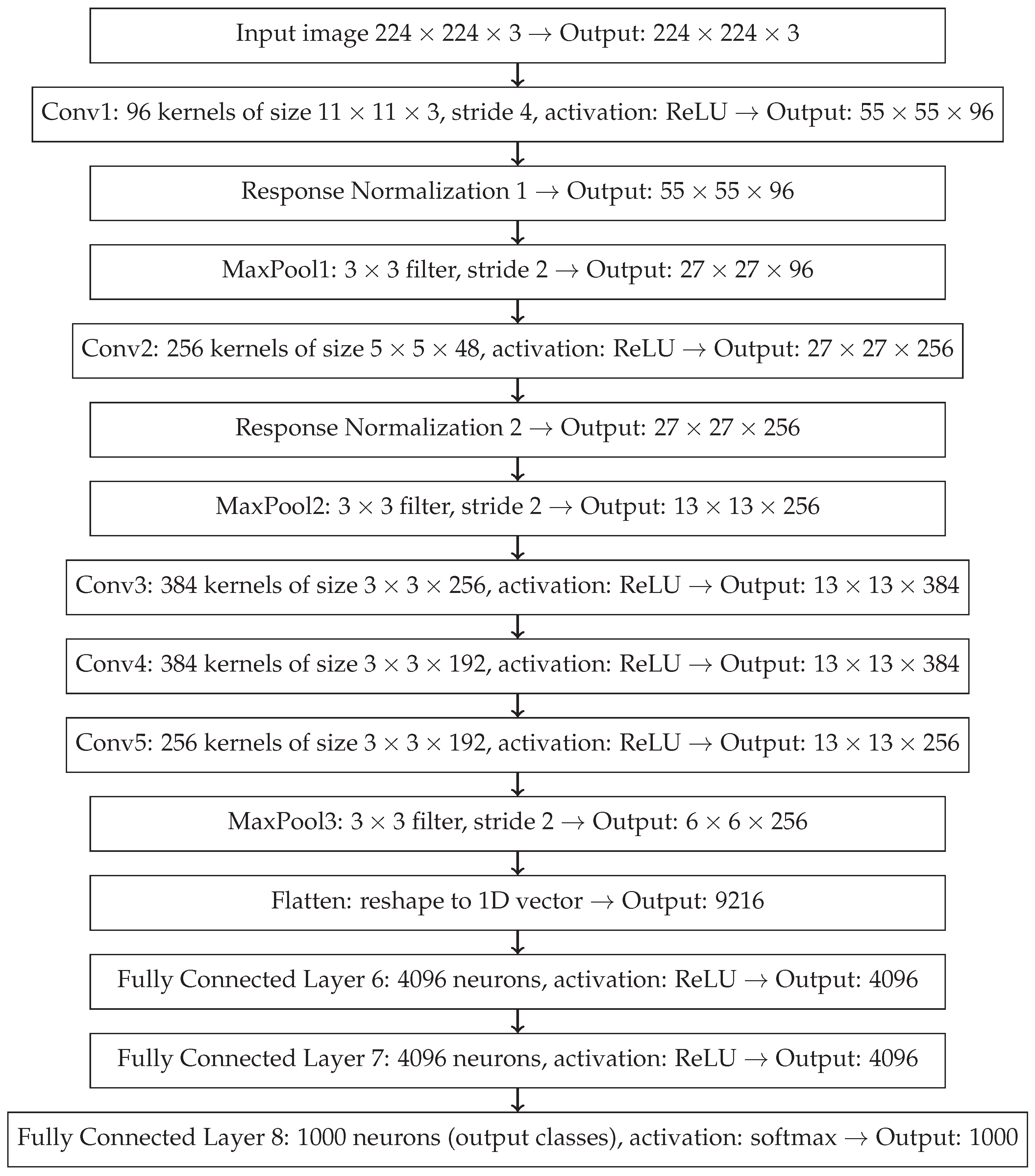

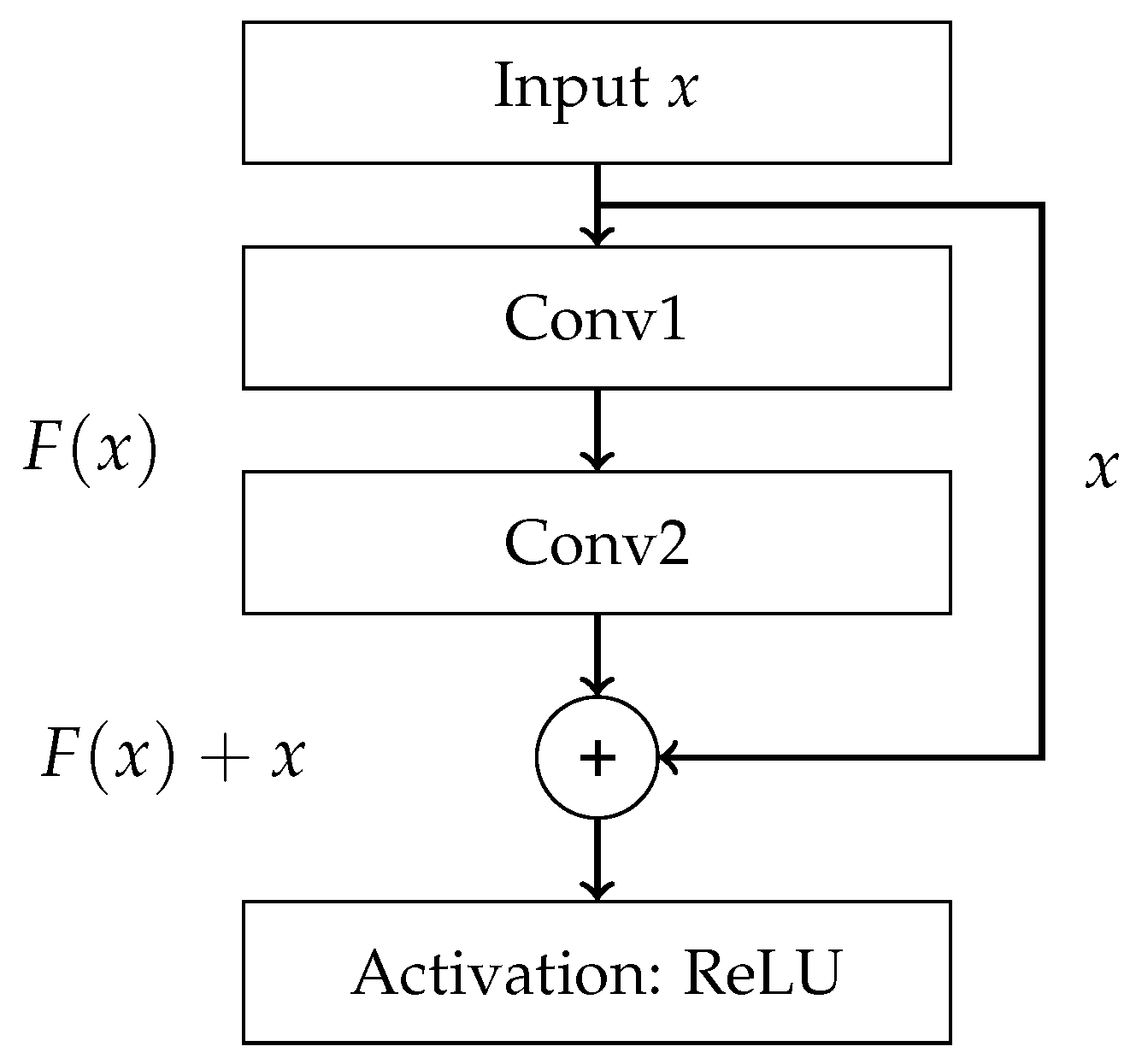

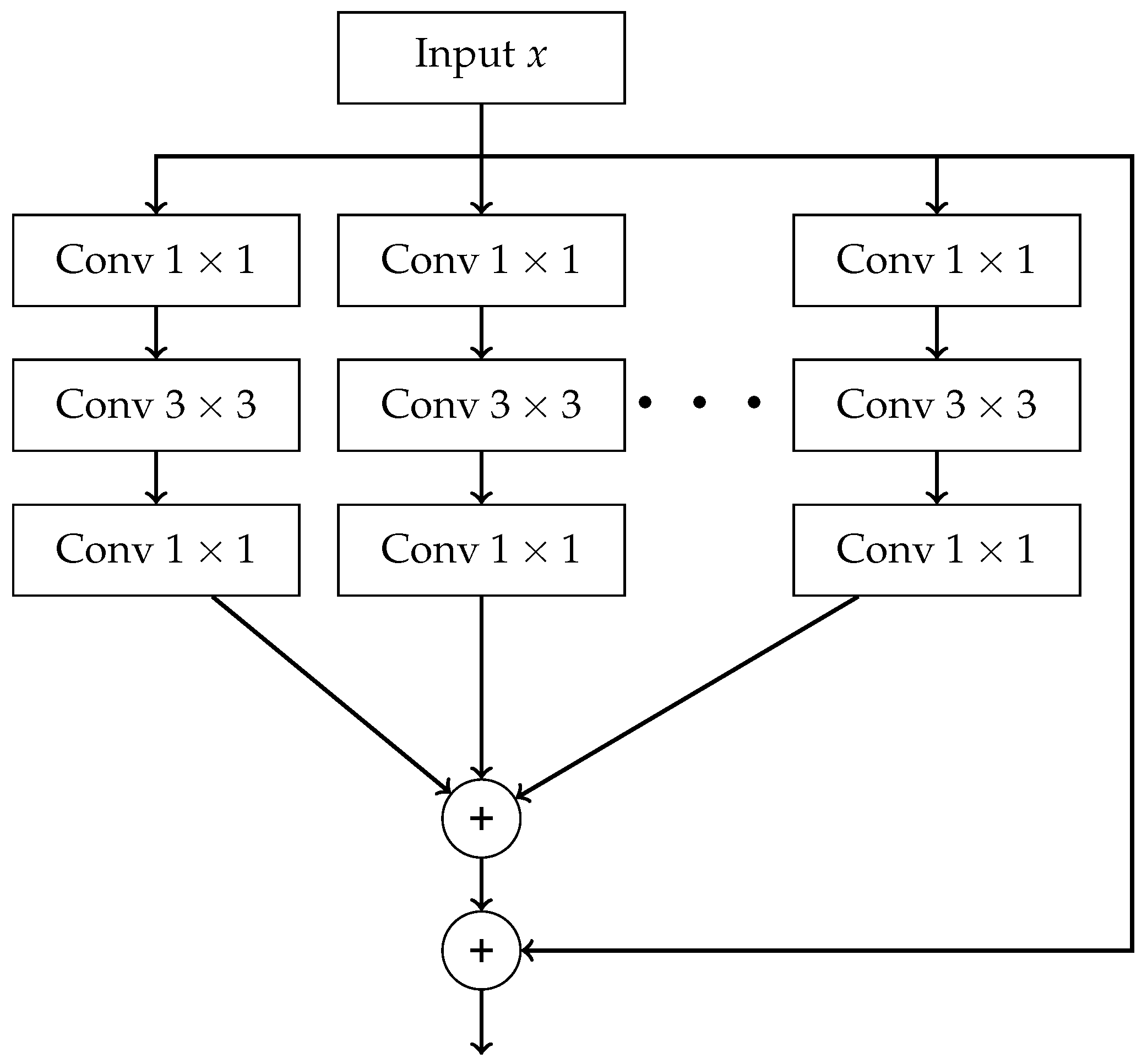

- End-to-End — final result is produced directly from raw data without any intermediate processing steps. Such processing can be carried out using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and its advanced variants, which includes models such as AlexNet, VGG16, ResNet, ResNeXt, and DenseNet.

- Gradient — each tree approximates the gradient of the loss function with respect to the current prediction.

- Boosting — combining many weak learners into a single strong model.

- 1.

- Assignment step — each data point is assigned to the cluster whose centroid is closest.

- 2.

- Update step — for each cluster , the centroid is updated as the mean of the data points assigned to cluster , as show in equation (21).

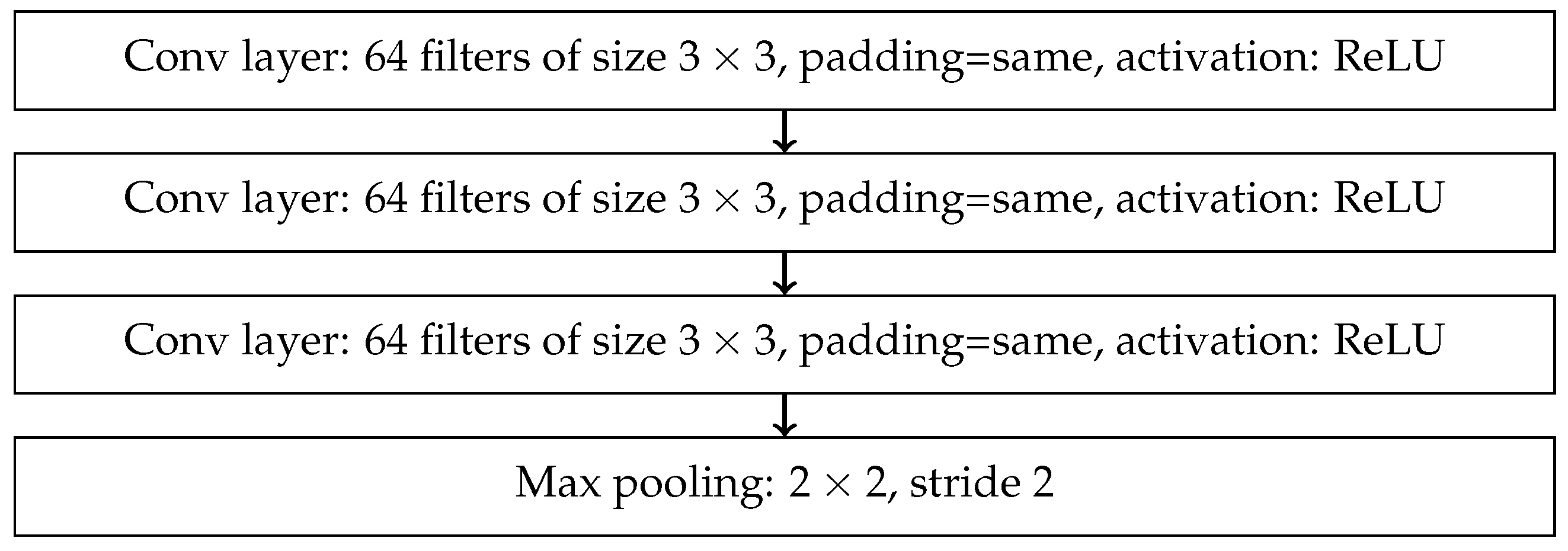

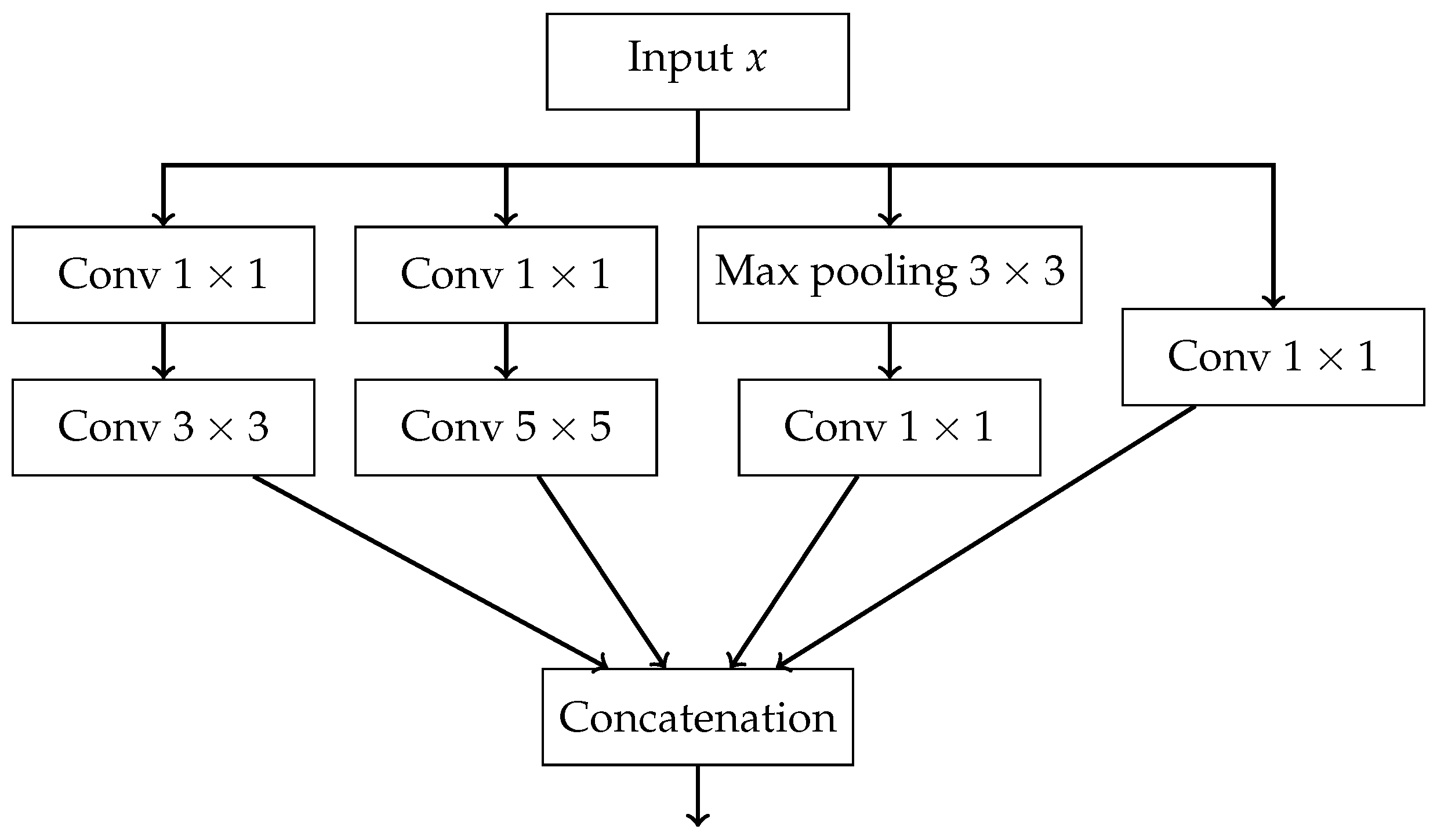

- a sequence of followed by convolutions,

- a sequence of followed by convolutions,

- a max pooling followed by convolution,

- a single convolution.

- The outputs of all paths are concatenated along the channel dimension.

6. Discussion on Biases and Limiations of AI Used in Histopathology

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| HTLV-1 | Human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type 1 |

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| CML | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia |

| HCL | Hairy-Cell Leukemia |

| PLL | Prolymphocytic Leukemia |

| LGLL | Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| MPAL | Mixed-phenotype Acute Leukemia |

| MM | Multiple Myeloma |

| FAB | French-American-British Classification |

| DIC | Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbour |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| RF | Random Forest |

| GB | Gradient Boosting |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RC | Ridge Classifier |

| MLP | Multilayer Perception |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

| WCSS | Within-Cluster Sum of Squares |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| FNR | False Negative Rate |

| FDA | Food and Drugs Administration |

| VGG | Visual Geometry Group |

Appendix A

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today, 2024. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today, Accessed: 2025-07-09.

- Medycyna Praktyczna – Podręcznik Pediatrii. Epidemiologia. Zagadnienia ogólne – Nowotwory wieku dziecięcego. https://www.mp.pl/podrecznik/pediatria/chapter/B42.71.13.1, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-09.

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2024, 74, 12–49, [https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.3322/caac.21820]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, F. Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer Journal 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.H.; Pawlina, W. Histology: A Text and Atlas. With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2019; p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukasaki, K. Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma. Hematology 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Hernandez, A.; Moturi, K.; Hanson, V.; Andritsos, L.A. Hairy Cell Leukemia: Where Are We in 2023?, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.; Bladek, P.; Goksu, B.; Murga-Zamalloa, C.; Bixby, D.; Wilcox, R. T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia: Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, and Treatment, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Drillet, G.; Pastoret, C.; Moignet, A.; Lamy, T.; Marchand, T. Large granular lymphocyte leukemia: An indolent clonal proliferative disease associated with an array of various immunologic disorders. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2023, 44, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.S.; Yohannan, B.; Gonzalez, A.; Rios, A. Mixed-Phenotype Acute Leukemia: Clinical Diagnosis and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; Catovsky, D.; Daniel, M.T.; Flandrin, G.; Galton, D.A.G.; Gralnick, H.R.; Sultan, C. Proposals for the Classification of the Acute Leukaemias French-American-British (FAB) Co-operative Group. British Journal of Haematology 1976, 33, 451–458, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaghan, M. Ryan, MSN, F.B. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Summary. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallek, M.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Eichhorst, B. Seminar Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1524–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epidemiological, genetic, and clinical characterization by age of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia based on an academic population-based registry study (AMLSG BiO). Annals of Hematology 2017, 96, 1993–2003. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckett, Y.; Chan, O. Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. Updated 2023 Aug 26. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459149/. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/chronic-myeloid-leukemia/about/statistics.html, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- Park, S.; Park, Y.H.; Huh, J.; Baik, S.M.; Park, D.J. Deep learning model for differentiating acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia in peripheral blood cell images via myeloblast and lymphoblast classification. Digital Health 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaretti, S.; Zini, G.; Bassan, R. Diagnosis and subclassification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Eden, R.E.; Coviello, J.M. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. Updated 2023 Jan 16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531459/. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- Penn Medicine. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. https://www.pennmedicine.org/conditions/chronic-myeloid-leukemia, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- Rai, K.R.; Sawitsky, A.; Cronkite, E.P.; Chanana, A.D.; Levy, R.N.; Pasternack, B.S. Clinical Staging of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 1975, 46, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, N.; Kars, A.; Kansu, E.; Ozdemir, O.; Barista, I.; Gullu, I.; Guler, N.; Ozisik, Y.; Dundar, S.; Firat, D. Comparison of Rai and Binet classifications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology 1997, 2, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Haematolymphoid tumours [Internet]. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2024. WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 11. Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

- Bain, B.J. Routine and specialised techniques in the diagnosis of haematological neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Pathology 1995, 48, 501–508, [https://jcp.bmj.com/content/48/6/501.full.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehkharghanian, T.; Mu, Y.; Tizhoosh, H.R.; Campbell, C.J. Applied machine learning in hematopathology, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Browman, G.P.; Neame, P.B.; Soamboonsrup, P. The Contribution of Cytochemistry and Immunophenotyping to the Reproducibility of the FAB Classification in Acute Leukemia. Blood 1986, 68, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, J.N.; Schmittmann, T.; Riechert, S.; Kramer, M.; Sulaiman, A.S.; Sockel, K.; Kroschinsky, F.; Schetelig, J.; Wagenführ, L.; Schuler, U.; et al. Deep learning identifies Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in bone marrow smears. BMC Cancer 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karar, M.E.; Alotaibi, B.; Alotaibi, M. Intelligent Medical IoT-Enabled Automated Microscopic Image Diagnosis of Acute Blood Cancers. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.; Khanna, K.; Singh, V. LeuFeatx: Deep learning–based feature extractor for the diagnosis of acute leukemia from microscopic images of peripheral blood smear. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musleh, S.; Islam, M.T.; Alam, M.T.; Househ, M.; Shah, Z.; Alam, T. ALLD: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Detector. In Proceedings of the Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. IOS Press BV; 2022; Vol. 289, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, M.; H, S.; L, J.A.; Gandomi, A.H. ALNett: A cluster layer deep convolutional neural network for acute lymphoblastic leukemia classification. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunadi, I.; Senan, E.M. Multi-Method Diagnosis of Blood Microscopic Sample for Early Detection of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Based on Deep Learning and Hybrid Techniques. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manescu, P.; Narayanan, P.; Bendkowski, C.; Elmi, M.; Claveau, R.; Pawar, V.; Brown, B.J.; Shaw, M.; Rao, A.; Fernandez-Reyes, D. Detection of acute promyelocytic leukemia in peripheral blood and bone marrow with annotation-free deep learning. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, N.; Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yang, S.; Xie, J.; Su, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cheng, Q.; et al. Diagnosing acute promyelocytic leukemia by using convolutional neural network. Clinica Chimica Acta 2021, 512, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, M.; Akkus, Z.; Jevremovic, D.; Nguyen, P.L.; Roh, D.; Al-Kali, A.; Patnaik, M.M.; Nanaa, A.; Rizk, S.; Salama, M.E. Classification of monocytes, promonocytes and monoblasts using deep neural network models: An area of unmet need in diagnostic hematopathology. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldú, L.; Merino, A.; Acevedo, A.; Molina, A.; Rodellar, J. A deep learning model (ALNet) for the diagnosis of acute leukaemia lineage using peripheral blood cell images. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałczyński, K.; Śmigiel, S.; Gackowska, M.; Ledziński, D.; Bujnowski, S.; Lutowski, Z. IoT application of transfer learning in hybrid artificial intelligence systems for acute lymphoblastic leukemia classification. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Method for Diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Based on ViT-CNN Ensemble Model. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Chou, F.I.; Ho, W.H.; Tsai, J.T. Classifying microscopic images as acute lymphoblastic leukemia by Resnet ensemble model and Taguchi method. BMC Bioinformatics 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dese, K.; Raj, H.; Ayana, G.; Yemane, T.; Adissu, W.; Krishnamoorthy, J.; Kwa, T. Accurate Machine-Learning-Based classification of Leukemia from Blood Smear Images. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia 2021, 21, e903–e914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferlach, T.; Pohlkamp, C.; Heo, I.; Drescher, R.; Hänselmann, S.; Lörch, T.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, C.; Nadarajah, N. Automated Peripheral Blood Cell Differentiation Using Artificial Intelligence - a Study with More Than 10,000 Routine Samples in a Specialized Leukemia Laboratory. Blood 2021, 138, 103–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.E.; Chen, P.; Medeiros, L.J.; Wistuba, I.I.; Jaffray, D.; Wu, J.; Khoury, J.D. Artificial intelligence strategy integrating morphologic and architectural biomarkers provides robust diagnostic accuracy for disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of Pathology 2022, 256, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Hu, J. Classification of acute myeloid leukemia M1 and M2 subtypes using machine learning. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.N.; Middeke, J.; Riechert, S.; Schmittmann, T.; Sulaiman, A.; Kramer, M.; Sockel, K.; Kroschinsky, P.; Schuler, U.; Schetelig, J.; et al. Deep learning detects acute myeloid leukemia and predicts NPM1 mutation status from bone marrow smears. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, M.; Guo, P.; Wei, Y.; Tan, Y.; Shi, H. Artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis of hematologic diseases based on bone marrow smears using deep neural networks. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, A.; Jha, R.K.; Sinha, R.; Jha, K. Automated detection and classification of leukemia on a subject-independent test dataset using deep transfer learning supported by Grad-CAM visualization. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Arabyarmohammadi, S.; Leo, P.; Meyerson, H.; Metheny, L.; Xu, J.; Madabhushi, A. Automatic myeloblast segmentation in acute myeloid leukemia images based on adversarial feature learning. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Guo, F.; Ni, X.; Hu, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Rapid screening of acute promyelocytic leukaemia in daily batch specimens: A novel artificial intelligence-enabled approach to bone marrow morphology. Clinical and Translational Medicine 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.L.; Huang, Z.B. An ensemble-acute lymphoblastic leukemia model for acute lymphoblastic leukemia image classification. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2024, 21, 1959–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawahar, M.; Anbarasi, L.J.; Narayanan, S.; Gandomi, A.H. An attention-based deep learning for acute lymphoblastic leukemia classification. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aby, A.E.; Salaji, S.; Anilkumar, K.K.; Rajan, T. Classification of acute myeloid leukemia by pre-trained deep neural networks: A comparison with different activation functions. Medical Engineering and Physics 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, V. Artificial Intelligence Powered Automated and Early Diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cancer in Histopathological Images: A Robust SqueezeNet-Enhanced Machine Learning Framework. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labati, R.D.; Piuri, V.; Scotti, F. All-IDB: The acute lymphoblastic leukemia image database for image processing. In Proceedings of the 2011 18th IEEE international conference on image processing. IEEE; 2011; pp. 2045–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Fišer, K.; Sieger, T.; Schumich, A.; Wood, B.; Irving, J.; Mejstříková, E.; Dworzak, M.N. Detection and monitoring of normal and leukemic cell populations with hierarchical clustering of flow cytometry data. Cytometry Part A 2012, 81A, 25–34, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/cyto.a.21148]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaian, S.; Madhukar, M.; Chronopoulos, A.T. Automated screening system for acute myelogenous leukemia detection in blood microscopic images. IEEE Systems Journal 2014, 8, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzu, L.; Caocci, G.; Ruberto, C.D. Leucocyte classification for leukaemia detection using image processing techniques. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2014, 62, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoh, S.C.; Srisukkham, W.; Zhang, L.; Todryk, S.; Greystoke, B.; Lim, C.P.; Hossain, M.A.; Aslam, N. An Intelligent Decision Support System for Leukaemia Diagnosis using Microscopic Blood Images OPEN. Nature Publishing Group 2015, 5, 14938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.; Singh, A.; Bhadauria, H.S.; Virmani, J. Computer Aided Diagnostic System for Detection of Leukemia Using Microscopic Images. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science. Elsevier B.V. 2015; Vol. 70, pp. 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Najafabadi, T.; Araabi, B. Automatic Recognition of Acute Myelogenous Leukemia in Blood Microscopic Images Using K-means Clustering and Support Vector Machine. Journal of medical signals and sensors 2016, 6, 183–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigorra, L.; Merino, A.; Alférez, S.; Rodellar, J. Feature Analysis and Automatic Identification of Leukemic Lineage Blast Cells and Reactive Lymphoid Cells from Peripheral Blood Cell Images. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.; Singh, A.; Bhadauria, H.S.; Virmani, J.; Devgun, J.S. Classification of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia using hybrid hierarchical classifiers. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2017, 76, 19057–19085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P.T. Blood Cells. Kaggle dataset, 2025. Downloaded from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/paultimothymooney/blood-cells.

- Rehman, A.; Abbas, N.; Saba, T.; Rahman, S.I.u.; Mehmood, Z.; Kolivand, H. Classification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia using deep learning. Microscopy Research and Technique 2018, 81, 1310–1317, [https://analyticalsciencejournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jemt.23139]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, S.; Tehsin, S. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia detection and classification of its subtypes using pretrained deep convolutional neural networks. Technology in Cancer Research and Treatment 2018, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, E.; Ramesh, D. Phase classification of chronic myeloid leukemia using convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology, RAIT 2018. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 6 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Guang, P.; Li, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Haque, N. AML, ALL, and CML classification and diagnosis based on bone marrow cell morphology combined with convolutional neural network: A STARD compliant diagnosis research. Medicine (United States) 2020, 99, E23154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandradevan, R.; Aljudi, A.A.; Drumheller, B.R.; Kunananthaseelan, N.; Amgad, M.; Gutman, D.A.; Cooper, L.A.; Jaye, D.L. Machine-based detection and classification for bone marrow aspirate differential counts: initial development focusing on nonneoplastic cells. Laboratory Investigation 2020, 100, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösler, W.; Altenbuchinger, M.; Baeßler, B.; Beissbarth, T.; Beutel, G.; Bock, R.; von Bubnoff, N.; Eckardt, J.N.; Foersch, S.; Loeffler, C.M.; et al. An overview and a roadmap for artificial intelligence in hematology and oncology. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2023, 149, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P.; Smyk, R. Comparison of thresholding algorithms for automatic overhead line detection procedure. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2022, pp. 149–155.

- Hough, P.V. Method and means for recognizing complex patterns, 1962. US Patent 3,069,654.

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E. Use of the Hough transformation to detect lines and curves in pictures. Communications of the ACM 1972, 15, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D.H. Generalizing the Hough transform to detect arbitrary shapes. Pattern recognition 1981, 13, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding machine learning: From theory to algorithms; Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals of statistics 2001, pp. 1189–1232.

- Cox, D.R. The regression analysis of binary sequences. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1958, 20, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1609.04747 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2005, 67, 301–320, [https://academic.oup.com/jrsssb/articlepdf/2967/2/301/49795094/jrsssb_67_2_301.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE transactions on information theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L. Machine Perception of Three-Dimensional Solids. PhD thesis, 1963.

- Sobel, I.; Feldman, G. A 3×3 isotropic gradient operator for image processing. Pattern Classification and Scene Analysis 1973, pp. 271–272.

- Prewitt, J.M.; et al. Object enhancement and extraction. Picture processing and Psychopictorics 1970, 10, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1409.1556 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1492–1500.

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4700–4708.

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 1–9.

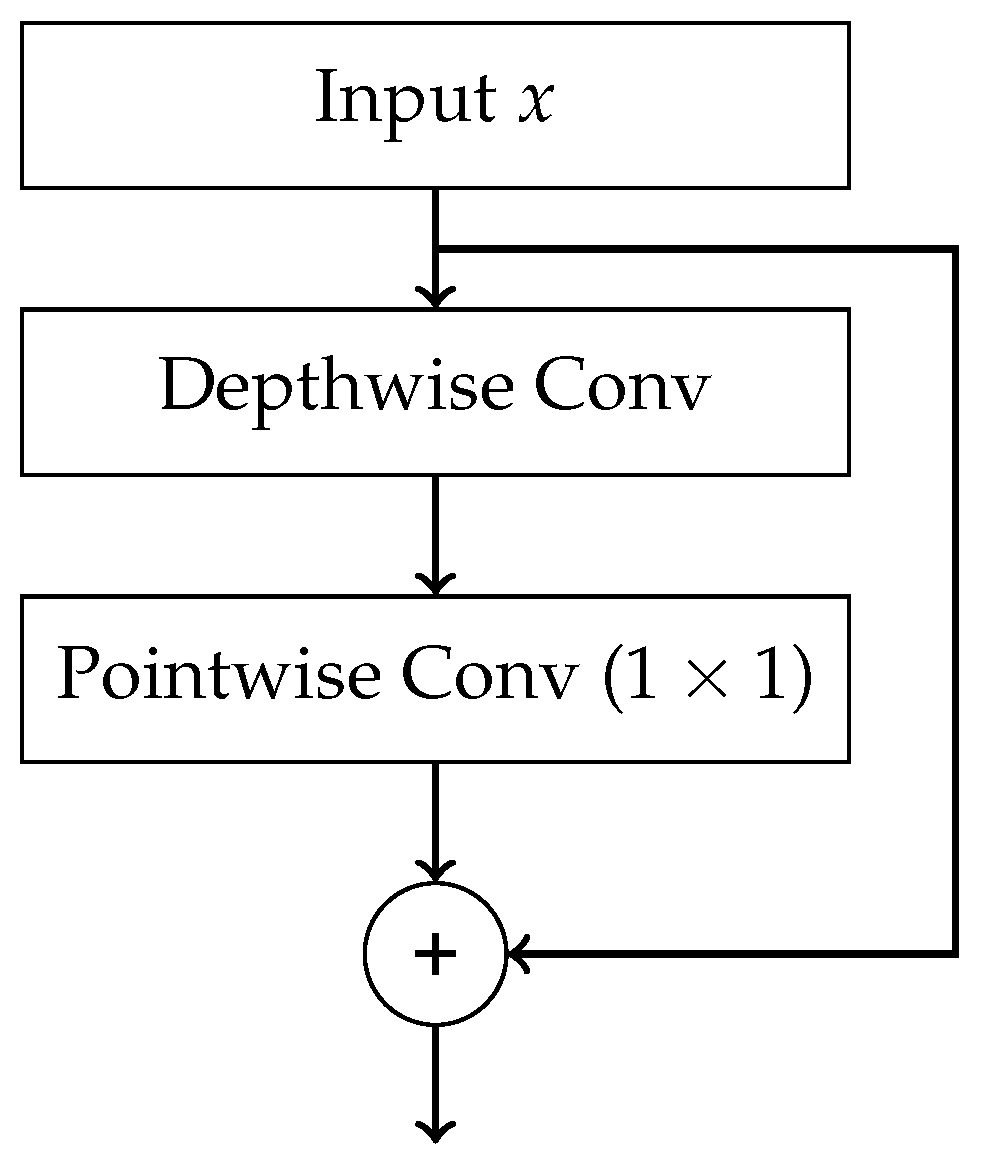

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1251–1258.

- Kazemi, et al.: Automatic recognition of AML in microscopic images. Technical report.

- Musleh, S.; Islam, M.T.; Alam, M.T.; Househ, M.; Shah, Z.; Alam, T. ALLD: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Detector. In Proceedings of the Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. IOS Press BV; 2022; Vol. 289, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, Y.H.; Huh, J.; Baik, S.M.; Park, D.J. Deep learning model for differentiating acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia in peripheral blood cell images via myeloblast and lymphoblast classification. Digital Health 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Guo, F.; Ni, X.; Hu, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Rapid screening of acute promyelocytic leukaemia in daily batch specimens: A novel artificial intelligence-enabled approach to bone marrow morphology. Clinical and Translational Medicine 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldú, L.; Merino, A.; Alférez, S.; Molina, A.; Acevedo, A.; Rodellar, J. Automatic recognition of different types of acute leukaemia in peripheral blood by Image Analysis. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2019, 72, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.T.; Muhsen, I.N.; Salama, M.E.; Owaidah, T.; Hashmi, S.K. Machine learning applications in the diagnosis of leukemia: Current trends and future directions, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mantri, R.; Khan, R.A.H.; Mane, D.T. An Efficient System for Detection and Classification of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Using Semi-Supervised Segmentation Technique. International Research Journal of Multidisciplinary Technovation 2025, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reta, C.; Altamirano, L.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Diaz-Hernandez, R.; Peregrina, H.; Olmos, I.; Alonso, J.E.; Lobato, R. Segmentation and classification of bone marrow cells images using contextual information for medical diagnosis of acute leukemias. PloS one 2015, 10, e0130805. [Google Scholar]

- Matek, C.; Schwarz, S.; Spiekermann, K.; Marr, C. Human-level recognition of blast cells in acute myeloid leukaemia with Convolutional Neural Networks. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Saini, L.M. Robust technique for the detection of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Power, Communication and Information Technology Conference (PCITC), 2015, pp. 657–662. [CrossRef]

- Rolls, G. An Introduction to Specimen Processing. https://www.leicabiosystems.com/knowledge-pathway/an-introduction-to-specimen-processing/, 2019. Accessed: 2025-07-22.

- Taqi, S.A.; Sami, S.A.; Sami, L.B.; Zaki, S.A. A review of artifacts in histopathology, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Balis, U.G.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Lujan, G.; Mcclintock, D.S.; Pantanowitz, L.; Parwani, A. Contemporary whole slide imaging devices and their applications within the modern pathology department: A selected hardware review, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Basak, K.; Ozyoruk, K.B.; Demir, D. Whole Slide Images in Artificial Intelligence Applications in Digital Pathology: Challenges and Pitfalls, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sellaro, T.L.; Filkins, R.; Hoffman, C.; Fine, J.L.; Ho, J.; Parwani, A.V.; Pantanowitz, L.; Montalto, M. Relationship between magnification and resolution in digital pathology systems. Journal of Pathology Informatics 2013, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, N.; Rahim, S.N.A.; Omar, W.F.A.W.; Zulkarnain, S.; Sinha, S.; Kumar, S.; Haque, M. Preanalytical Errors in Clinical Laboratory Testing at a Glance: Source and Control Measures. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhleh, R.E.; Idowu, M.O.; Souers, R.J.; Meier, F.A.; Leonas, G.B. Mislabeling of Cases, Specimens, Blocks, and Slides A College of American Pathologists Study of 136 Institutions. (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:969-974) 2011.

- Packer, M.D.C.; Ravinsky, E.; Azordegan, N. Patterns of Error in Interpretive Pathology: A Review of 23 PowerPoint Presentations of Discordances. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2021, 157, 767–773, [https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article-pdf/157/5/767/49102733/aqab190.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehan, L.M.; Lewis, J.S.; Mehrad, M.; Ely, K.A. Patterns of Major Frozen Section Interpretation Error: An In-Depth Analysis From a Complex Academic Surgical Pathology Practice. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2023, 160, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 18 grudnia 2017 r. w sprawie standardów organizacyjnych opieki zdrowotnej w dziedzinie patomorfologii. Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, poz. 2435/2017, Dz.U. 2017 poz. 2435, 2017. Available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170002435. Accessed: 2025-07-22.

- Mutter, G.L.; Milstone, D.S.; Hwang, D.H.; Siegmund, S.; Bruce, A. Measuring digital pathology throughput and tissue dropouts. Journal of Pathology Informatics 2022, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.G.; Crook, M. Pathology tests: is the time for demand management ripe at last? Technical report, 2003.

- Feng, C.; Liu, F. Artificial intelligence in renal pathology: Current status and future, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Neto, P.C.; Montezuma, D.; Oliveira, S.P.; Oliveira, D.; Fraga, J.; Monteiro, A.; Monteiro, J.; Ribeiro, L.; Gonçalves, S.; Reinhard, S.; et al. An interpretable machine learning system for colorectal cancer diagnosis from pathology slides. npj Precision Oncology 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.M.; Pereira, E.M.; Salles, P.G.; Godrich, R.; Ceballos, R.; Kunz, J.D.; Casson, A.; Viret, J.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Ferreira, C.G.; et al. Independent real-world application of a clinical-grade automated prostate cancer detection system. Journal of Pathology 2021, 254, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices, 2024. Accessed: 2025-07-20.

| AML | ALL | CML | CLL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age of patient | 65 years [15] | 11 years [16] | 66 years [17] | 70 years [18] |

| Onset and disease dynamics | acute | acute | gradual | gradual |

| Subtypes, | M0-M7 (FAB) | B-ALL, T-ALL | numerous (based on genetic abnormalities) | indolent/aggressive |

| Percentage of blasts in pathological specimen required for diagnosis | 10% or 20% depending on mutations [19] | 20% lymphoblasts [20] | less than 10% in chronic phase, more than 20% in blastic phase [21] | criterion not defined for CLL |

| Staging scales | - | - | chronic, accelerated, blastic phases [22] | RAI [23], Binet [24] |

| Dataset name | Year | Images | Resolution | Magnification | Problem / Type | Citations | Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | 2022 | 6 963 | X | 50 | classification | 55 | bone marrow smear |

| [30] | 2022 | 445 | X | X | classification | 47 | blood smear |

| [31] | 2022 | 18 365 | X | X | classification | 113 | blood smear |

| [32] | 2022 | 260 | X | classification | 6 | X | |

| [33] | 2022 | 10 661 | X | X | classification | 43 | X |

| [34] | 2022 | 368 | X | classification | 77 | X | |

| [35] | 2023 | 1 625 full micrographs and 20 004 single cell | 100 and 50 | classification | 40 | peripheral blood and bone marrow | |

| [36] | 2021 | 13 504 | X | X | classification | 40 | bone marrow smear |

| [37] | 2021 | 935 | 100 | classification | 13 | peripheral blood | |

| [38] | 2021 | 16 450 | X | X | classification | 140 | peripheral blood |

| [39] | 2021 | 260 | X | X | classification | 25 | blood smear |

| [40] | 2021 | 10 661 | X | X | classification | 129 | X |

| [41] | 2021 | 12 528 | X | X | classification | 23 | X |

| [42] | 2021 | 520 | 100 | classification | 90 | blood smear | |

| [43] | 2021 | 8 425 | 10 | classification | 8 | blood smear | |

| [44] | 2022 | 125 | X | 20 | classification | 41 | lymph node biopsy |

| [45] | 2022 | 122 | X | classification | 36 | bone marrow smear | |

| [46] | 2022 | 10 632 | X | 50 | classification | 86 | bone marrow smear |

| [47] | 2023 | 11 788 full micrographs and 131 300 single cell | X | X | classification | 29 | bone marrow smear |

| [48] | 2023 | 1 250 | 40 and 100 | classification | 60 | blood smear | |

| [19] | 2024 | 42 386 single cell | X | classification | 4 | peripheral blood | |

| [49] | 2024 | 204 | X | X | segmentation | 8 | cytology |

| [50] | 2024 | 15 719 | X | 10 and 100 | classification | 2 | bone marrow smear |

| [51] | 2024 | 3 527 | X | X | classification | 7 | X |

| [52] | 2024 | 362 | X | classification | 27 | X | |

| [53] | 2025 | 669 single cell | X | X | classification | 4 | X |

| [54] | 2025 | 3 256 | X | classification | X | blood smear | |

| [55] | 2011 | 109 | 300 to 500 | segmentation | 641 | blood smear | |

| [55] | 2011 | 260 | 300 to 500 | classification | 641 | blood smear | |

| [56] | 2011 | 123 | X | X | classification | 57 | bone marrow or peripheral blood |

| [57] | 2014 | 80 | X | classification | 193 | X | |

| [58] | 2014 | 33 | and | 300 to 500 | classification | 369 | X |

| [59] | 2015 | 180 | X | X | classification | 172 | blood smear |

| [60] | 2015 | 130 | X | classification | 150 | X | |

| [61] | 2016 | 330 | 100 | classification | 83 | X | |

| [62] | 2017 | 916 | X | X | classification | 50 | peripheral blood |

| [63] | 2017 | 260 | X | X | classification | 130 | X |

| [64] | 2018 | 410 | X | classification | X | blood smear | |

| [65] | 2018 | 330 | X | 100 | classification | 359 | X |

| [66] | 2018 | 368 | X | classification | 377 | X | |

| [67] | 2018 | 536 | X | classification | 10 | X | |

| [68] | 2020 | 104 | 100 | classification | 52 | bone marrow smear | |

| [69] | 2020 | 17 | X | 40 | classification | 111 | bone marrow aspirate |

| Reference | Material | Diagnose | Use of the model | Dataset size | Segmentation method | Classifier | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [96] | blood smear, bone marrow | AML | detection of AML | 330 | pattern recognition-based | SVM | 96% accuracy |

| [62] | blood smear | AML | telling reactive lymphoid cells from myeloid and lymphoid blasts | 696 | pattern recognition-based | SVM | 82% accuracy |

| [57] | blood smear | AML | AML detection + classification into subtypes | 80 (40 ALM and 40 non-ALM) | k-means (k=3) | SVM | 98% accuracy |

| [97] | blood smear | ALL, AML | classification | 15,000 images (80/20 split, 10-fold CV for ML) | None; image resizing | DenseNet121 (DL); SVM, KNN, RF, DT (ML) | DenseNet121 → Acc: 98.7%, Prec: 98.9%, Rec: 98.3%, F1: 98.6%; SVM → Acc: 96.2% |

| [53] | blood smear | ALL, AML | classification of leukemia types | ALL-IDB (260) + LISC (257) | HSV color space + k-means clustering | Hybrid CNN + Vision Transformer (HCVT) | ALL-IDB: 99.12%, accuracy LISC: 97.28% accuracy |

| [98] | blood smear | AML, ALL | classification of AML vs ALL | 15,684 images (104 AML, 86 ALL patients) | no segmentation (weakly supervised learning on full smear images) | EfficientNet-B4 (transfer learning) | AUC = 0.981, accuracy = 95.3% |

| [99] | bone marrow smear | AML, ALL | detection | 15,719 images from 83 APL patients + 118 control samples | Color-based segmentation of karyocytes | CNN with attention modules (CELLSEE); backbones: ResNet18, ResNet34, ResNet50 | AUC = 0.9708 (CELLSEE50); Accuracy = 93.8%; Recall = 90.8% |

| [100] | blood smear | AML, ALL | X | 4394 | X | Naive Bayes, K-NN, RF, SVM | 85,8% accuracy |

| [48] | bone marrow | ALL/AML | classification into 21 morphological categories | 17152 | manual segmentation | CNN (ResNeXt) | 91.7% accuracy, avg F1-score 87.3% |

| [43] | blood smear | AML, CLL, MDS, CML, etc. | differential cell classification | 10,082 patients / 4.9M images (training: 8,425) | automatic cell cropping using scanning system | Xception | 96% accuracy; 91% blast detection; 95% concordance for pathogenic cases |

| [101] | blood smear, bone marrow | ALL, AML, CML, CLL | leukemia diagnosis | X | various (thresholding, morphological ops, clustering) | SVM, k-NN, ANN, CNN, DT, Naive Bayes, RF | accuracy ranges from 85% to >99% depending on study |

| [69] | bone marrow | AML, MM (tested), nonneoplastic (trained) | detection and classification tasks, using a two-stage system | 10,000 annotated cells (9269 nonneoplastic, plus AML, MM cases) | Faster R-CNN–based detection | VGG16 convolutional network | 97% accuracy AML |

| [102] | blood smear | ALL | segmentation and classification of blast cells | ALL-IDB: 559 | k-means | custom CNN (8 layers) | accuracy: 100% ALL detection; 99% subtypes classification |

| [54] | peripheral blood smear | Acute leukemia, MDS, CML | Automated blast detection | 114 patient samples; 100 leukocytes per smear | automated image capture and classification; no manual segmentation | CellaVision DM96 (proprietary pattern recognition system) | Sens: 93.3%, Spec: 86.8%, PPV: 87.9%, NPV: 92.6%, Acc: 90.4% |

| [103] | bone marrow | ALL | diagnosis of ALL, classification of ALL into subtypes | 633 | Pattern-recognition based | KNN, RF, SL, SVM, RC | 94% accuracy, 92% AML vs ALL |

| [37] | blood smear | ALL | classification of full smear image | 520 images; 80/20 train/test split | None; resized and normalized full images | Custom CNN (4 conv layers + dense layers) | Acc: 96.37%, Prec: 96.00%, Rec: 97.00%, F1: 96.48% |

| [49] | blood smear | ALL | classification | 392 cells (236 ALL, 156 normal), 108 images; 70/10/20 split | Manual cropping of WBC patches (224×224); no segmentation network | Vision Transformer (ViT); ViT-FF variant | Acc: 98.72%, Prec: 98.81%, Rec: 98.73%, F1: 98.72% |

| [40] | blood smear | ALL | classification | 20,000 images | Pre-segmented single-cell images; DERS augmentation | ViT + EfficientNet-b0 (ensemble, weighted sum 0.7/0.3) | Accuracy: 99.03%, Precision: 99.14% |

| [41] | blood smear | ALL | localization + classification | 392 cells (236 blast, 156 normal), 108 images | UNet (integrated in end-to-end model) | UNet + ResNet18 (ALL-NET architecture) | Acc: 98.68%, Prec: 98.70%, Rec: 98.80%, F1: 98.75% |

| [51] | blood smear | ALL | classification of leukemic vs normal cells | 260 cell images | manual cropping | custom CNN + k-NN, SVM, RF | up to 99.61% accuracy |

| [52] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification | 260 cell images | manual cropping | VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3 + GLCM + SVM, k-NN | up to 99.17% accuracy |

| [33] | blood smear | ALL | feature extraction and classification of leukemic cells | 234 cell images | manual cropping | VGG16, ResNet50, DenseNet121 + SVM, k-NN, RF, DT | up to 99.14% accuracy |

| [35] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB1: 108 images (59 ALL, 49 healthy) | HSV color space + color thresholding | VGG16, ResNet50, AlexNet + SVM, RF, KNN | ResNet50+SVM: 99.12% accuracy, 100% sensitivity, 98.1% specificity |

| [33] | blood smear | ALL | feature extraction and classification of leukemic cells | 234 cell images | manual cropping | VGG16, ResNet50, DenseNet121 + SVM, k-NN, RF, DT | up to 99.14% accuracy |

| [29] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB: 260 images (150 ALL, 110 healthy) | adaptive histogram equalization + Gaussian filtering | custom CNN | 99.3% accuracy, 98.7% sensitivity, 100% specificity |

| [45] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB1: 108 images (59 ALL, 49 healthy) | HSV color space + thresholding + morphological operations | VGG16 + SVM, KNN, ensemble (bagged trees) | Ensemble: 99.1% accuracy, 100% recall; SVM: 98.1% accuracy |

| [67] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB1: 108 images | thresholding + morphological operations + K-means | SVM, compared with k-NN, Naive Bayes, Decision Tree | 94.23% accuracy, 92.13% precision, 95.55% recall |

| [42] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB1: 108 images, ALL-IDB2: 260 cells | thresholding + morphological operations | CNN (13 layers) | 99.1–99.33% accuracy; >98% sensitivity and specificity |

| [35] | blood smear | ALL | detection and classification of ALL | ALL-IDB1: 108 images (59 ALL, 49 healthy) | HSV color space + color thresholding | VGG16, ResNet50, AlexNet + SVM, RF, KNN | ResNet50+SVM: 99.12% accuracy, 100% sensitivity, 98.1% specificity |

| [59] | blood smear | ALL | ALL detection, classification into subtypes | 180 | pattern recognition-based | MLP, SVM, EC | 97% accuracy |

| [104] | blood smear | ALL | diagnosis of ALL and classification into subtypes (L1, L2) | 14692 | Lab color space + k-means clustering + morphology | CNN | 0,99 AUC |

| [63] | blood smear | ALL | classification into subtypes | 260 | threshold-based | SVM, SSVM, KNN, ANFIS, PNN | 99% accuracy |

| [44] | blood smear | ALL | detection + classification ALL into subtypes | 180 | SDM-based clustering + simple morphological operations | MLP, SVM, Dempster-Shafer ensemble | 96,67% accuracy SVM, 96,72% accuracy Dempster-Shafer |

| [60] | blood smear | ALL | ALL detection | 130 | threshold-based | SVM | 90% accuracy |

| [66] | blood smear | ALL | detection of ALL, classification into subtypes | 760 | X | DCNN | accuracy for detection 99,50%, accuracy for classification 96,06% |

| [65] | bone marrow | ALL | classification of ALL into subtypes | 330 | Threshold-based | CNN | 97,78 % accuracy |

| [58] | blood smear | ALL | ALL detection | 33 | threshold-based | SVM | 92% accuracy |

| [105] | blood smear | ALL | ALL detection | 45 | pattern recognition-based | ANN, KNN, k-means, SVM | 100% specific, 95% sensitive |

| [36] | blood smear | Leukemia (via blast detection among WBCs) | localization + Classification | 400 WBCs from 260 images | Manual cropping using ground truth; pre-processing: histogram equalization, morphology | AlexNet + LBP + HOG → SVM | Acc: 97.5%, Prec: 96.8%, Rec: 95.3%, F1: 96.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).