Methods

Many authors have described the mathematical foundations and calculation equations for Loop Analysis, and they are not repeated here (Levins, 1974, 1975, 1998; Dambacher et al., 2003a, b, 2007; Wright & Lane, 1986; Lane, 2024a). While applications of this qualitative network technique include studies of a range of terrestrial and aquatic ecological systems, many ecologists are using Loop Analysis for improving causal understanding for marine Ecosystem-Based Management for social-ecological systems (Babcock, et al., 2016; Carey, et al., 2013; Coll, et al. (2019); Martone, et al., 2017; Metcalfe, et al., 2013; Ortiz & Levins, 2017; Reum et al., 2015; Wildermuth, et al., 2018; Lane, 1998, 2021). Loop analysis focuses on delineating the feedbacks in ecosystems and has roots in cybernetics. As a signed digraph technique, Loop Analysis is also a valuable methodology for Relational Biology, which emphasizes network configurations, such as food webs, by examining the overall network arrangement in contrast to the reductionist approach of focusing on node composition. Iñiguez et al. (2020) delineated the differences between graphs and networks at the mesoscale of ecosystems.

Loop models contain a set of nodes, links or edges, paths or pathways, and loops. An arrowhead is used to denote a positive effect on the node it touches, and a circlehead is used to denote a negative effect on the node it touches. These links represent the Community Matrix's traditional alpha values or interaction coefficients with intra-specific interactions along the main diagonal and inter-specific interactions filling the off-diagonal elements of the matrix. The external drivers of the model system, also referred to as parameter inputs in Loop Analysis, are designated by a larger but detached arrowhead for a positive effect on the node it touches and a similar circlehead for a negative input. The term, ‘driver’, is used here for consistency. The signs (0, +, -) of paths and loops are calculated via algebraic multiplication of the signs of their respective links. A path of X nodes has X-1 links, whereas a loop of X nodes has X links. Loops as closed paths are feedbacks. Feedback is defined as the effect of a node on itself through intervening nodes, resulting in closed loops of circular causality embedded in dynamic systems. Negative feedback stabilizes systems, allowing a thermostat, for example, to maintain a stable internal environment, or homeostasis. Positive feedback causes a system to continue its current trajectory while amplifying deviations, which eventually lead to the system's disintegration or it spins out of control, increasing uncontrolled, resulting in an unstable outcome in either case.

Using calculation equations, it is possible to determine the changes in standing crop for each node given that a driver has impacted the network and that initial impact is carried through all operating pathways. Predictions are entered into a square matrix known as the Community Effects Matrix, and predictions for a single driver to a node are read across its corresponding row. If desired, a correlation matrix can be calculated for each row. Turnover rates of node abundances can usually be inferred from the standing crop results for adjacent nodes. The modeller can calculate feedback at every level N for a system of 1 to N nodes and determine probable stability using the two Routh-Hurwitz criteria: (1) the system must have more negative feedback than positive, and (2) short negative loops are more stabilizing than long ones. Lever et al. (2022) also concluded that long negative loops are more destabilizing than short negative loops. As a qualitative technique, Loop Analysis does not deal directly with the strength of the links. The approach does not quantify flows of matter and energy inputting into an ecosystem, transversing several ‘black boxes’, and then exiting as output to the environment, whereby feedback is defined as a part of the output being used as an input. Thus, every loop is a feedback whose sign is determined by multiplying the algebraic signs of its links. It is assumed that each link may transmit information, matter, or energy, singularly or in combination.

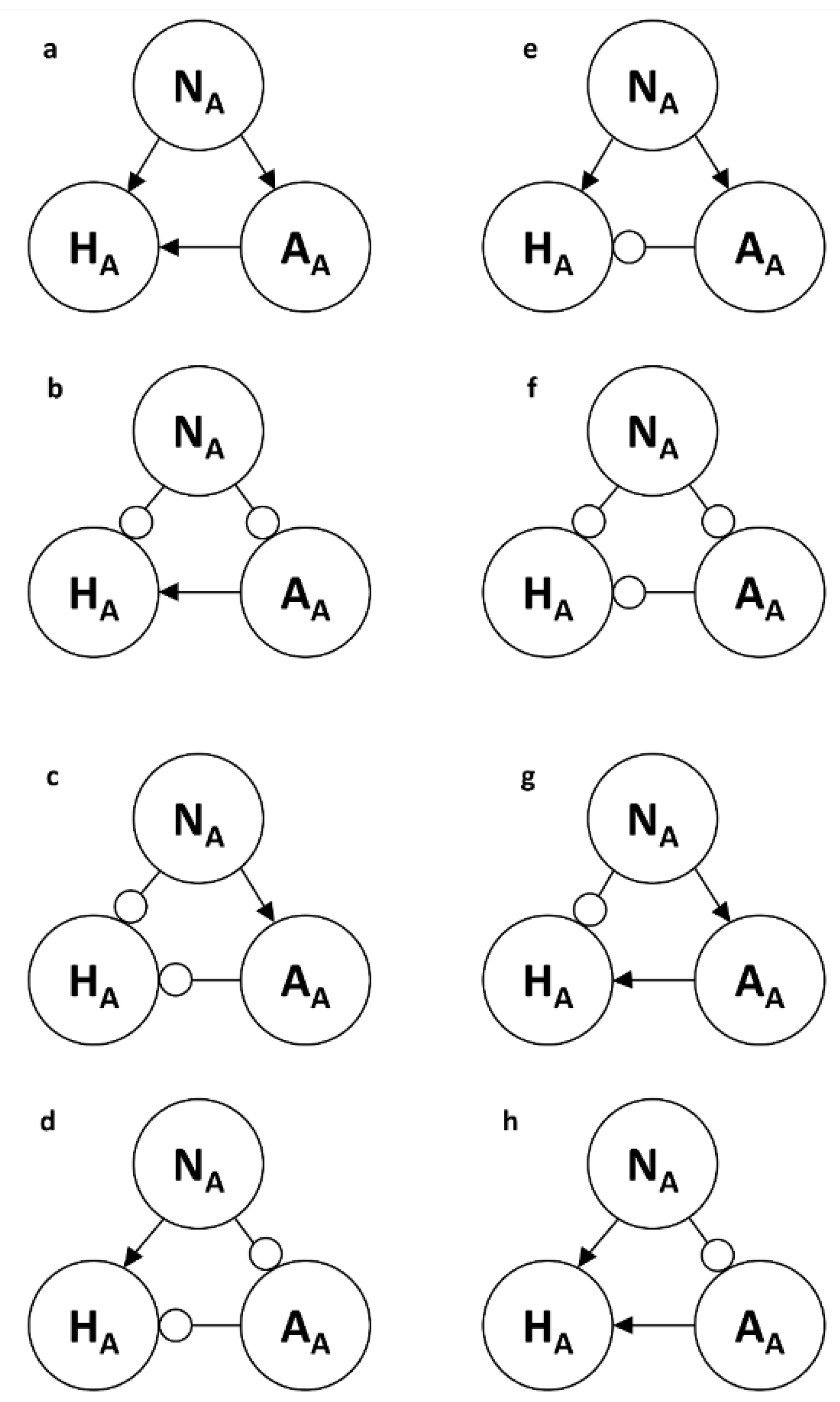

As a qualitative technique, Loop Analysis offers considerable flexibility compared to other modelling techniques. The nodes do not need to be represented in the same units (for example, numbers of individuals, grams of carbon, kilocalories of energy). In addition, there are nine mathematically possible qualitative link types between each pair of nodes, including the null case, so Loop Analysis can include all pairwise interactions, whether trophic or non-trophic. All N2 elements of the community matrix can be used, giving considerable flexibility to the range of interactions that can be studied. Many food webs represent a predator-prey interaction with only a single link and one arrowhead touching the predator. This impoverishes the potential ecological information and provides an unrealistic view of both pathways and loops in ecological systems, as no link is envisioned from the predator to the prey, only from the prey to the predator. Feedback is incompletely represented. When an ecosystem is represented by a set of models, two loop nodes can exhibit several different relationships (qualitative links) over an annual cycle; these links are termed ‘volatile’.

In Loop Analysis, a predator-prey pair constitutes a feedback loop of length two, and causality flows both ways as the predator is helped (+) and the prey is harmed (-). Frequently, multiple pathways between two nodes can produce ambiguous predictions that can only be resolved by semi- or full quantification (Lane & Levins, 1977). Those operating pathways can be identified and distinguished from those that do not, since each valid pathway must possess a complement in which non-path nodes are part of one or more disjunct feedback loops that share no nodes in common. Patten et al. (2011) concluded, “Pathways, in ecosystems, and across landscapes serve to structure, canalize, and otherwise constrain contemporary interactions. Several network properties, both structural and functional, can also be calculated using Loop Analysis (Lane, 2016, 2018a, 2024a).

Most loop analysis modeling has been used in two ways. First, in hypothetical or Type I loop modelling, the investigator constructs the loop model from their conceptual view of what the key nodes and links structure the system. The model construction is hypothetical. Most Type 1 models consist of fewer than ten to twelve nodes since intuition is increasingly strained as the number of nodes increases arithmetically. In contrast, the number of links can potentially increase geometrically. Thus, these models are often limited to fewer nodes and links than ecological reality necessitates, but even so, they can facilitate the comparison of hypotheses and management options (Babcock et al., 2016). Often, self-damping loops (short negative self-loops) are inserted to introduce more stability. However, these can be positioned arbitrarily at the expense of biological reality, and sometimes they can create unnecessary ambiguity (Lane, 2021).

Lane (1986; 2016; 2018a) developed Type II Loop Analysis using marine plankton data sets to construct larger loop models via a data-based procedure by comparing changes in the loop nodes in the field or laboratory with model predictions. These models are termed ‘biologically reasonable’. Ecological Skeletons summarize the most frequent nodes and links found in a set of loop models of these biologically reasonable networks, thus significantly reducing the number of potential ecosystem representations. Ecological Skeletons can also summarize loop models structures across two or more ecosystems, producing core models. Type II Loop Analysis facilitates the identification of causal pathways that explain abundance changes observed in the natural system, as well as the entry points and signs of external drivers. This reveals internal causal relationships that may operate as system constraints. Loop Analysis is a holistic methodology in that all nodes, links, and complement feedbacks are simultaneously involved in each prediction and in identifying causal relationships, such as an operating pathway, like a trophic cascade or escalade. Lane (2024a) described the step-by-step process of conducting Type II Loop Analysis and discussed its algorithmic and non-algorithmic features.

The community effects matrix (CEM) for each composite network was calculated using equations described in Dambacher et al. (2003a). Firstly, the matrix describing all directed changes from a community matrix (CM) is,

It is equivalent to the negative of the inverse of the community matrix (-CM

-1) and Levins’ original Loop Analysis algorithm. To account for cases where an equal number of positive and negative feedback cycles lead to an ambiguous effect of one node on another, the absolute-feedback (Taf) and weighted-predictions (W) matrices are calculated as,

where T is the matrix transpose. When W

ij = 1, all complementary feedback cycles are of the same sign, leading to complete sign determinacy. W

ij = 0 indicates equal positive and negative feedback cycles leading to complete sign ambiguity. When finalizing the community effects matrix, positive and negative M

ij values were replaced with ‘+’ and ‘- ‘symbols. If W

ij = 0, the corresponding M

ij zero value was replaced with a ‘?’ symbol to denote sign ambiguity.

System stability was assessed by evaluating each system against the two “Hurwitz criteria” described in Dambacher et al. (2003b), derived from Hurwitz’s principal theorem (Hurwitz [1895] 1964). For a system to be considered stable, these conditions state that:

Connectivity (C

1) and linkage density (C

2) were calculated for each model as,

where L designates the number of non-zero links and N the number of nodes in the network.

The number of auto-regulatory or self-loops was counted by tallying the number of positive and negative loops of length one on the diagonal of the community matrix. The two-node feedback loops were counted by counting link pairs that travel from a starting node to a neighbouring node and back to the starting node. Three- and four-node feedback loop motifs and three-node feedforward, bi-parallel, and bi-fan motifs were tallied by finding the number of occurrences of each motif in the network using the ‘subgraph_isomorphisms’ igraph function. To avoid counting motif duplicates (such as the loops A-B-C-A and B-C-A-B, as they represent the same motif functionally), the number of feedback loops found was divided by the nodes they contained, and the number of bi-fan motifs was divided by two. Feedback loop signs and feedforward loop types, as well as whether they led to ambiguous or unambiguous effects, were calculated by analyzing the signs of the links forming each feedforward loop. These results are detailed in separate tables.

The significance of the network motifs from composite model 16 was tested against 500 randomly generated networks. The Erdős-Rényi (1959) G(n, m) random graph model was used to generate random networks with the same number of nodes (21) and edges (69) as the composite model. The signs (-, +) were randomly assigned to each edge with equal probability. The mean and standard deviation of the number of motifs were calculated over all 500 random networks. Z-scores comparing those numbers to those found for the composite model 16 were calculated. At α = 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01, absolute z-score values of over 1.645, 1.960, and 2.576, respectively, were considered statistically significant, indicating a significant difference in the number of motifs between the random and composite networks. All analyses were performed using the R statistical software (R Core Team, 2020). Analyses involving motifs were performed using the R ‘igraph’ package (Csárdi & Nepusz, 2006) and associated functions.

Keystone Species and Node Relevance

Notions of keystoneness and species control, which are defined as one species changing the abundance of another, are beginning to be seen in studies of ecological networks using measures of centrality, percolation ‘experiments’ that involve removing species sequentially, and in structural controllability of asymmetric pollinator food webs (Cagua, et al., 2019). Designating the first node of change as a controller, akin to a keystone predator, can be problematic, and this special status is sometimes overstated. A single population designated as important is termed a keystone, named after the ‘keystone’ at the top of a stone arch, affording a strategic position in holding the structure together.

Initially, a keystone species was a top predator. Over time, the keystone concept has been expanded to include other species such as keystone prey, ecological engineers, super spreaders, teachers, etc. In addition, the array of keystone actions included other roles besides control per se. For example, Trosvik and de Muinck (2015) identified four species groups that have different keystone roles in the human gastrointestinal gut microbiota. Although keystones are always internal components of a food web, it is not as easy to conceptualize a small diatom as a keystone species compared to a hungry shark with glistening, sharp teeth. A keystone species is a priori not equal to the rest (Power et al., 1996). It is often defined as “having a disproportionately large effect on community dynamics related to its abundance” (Modlmeier et al., 2014). These authors provided clarification of the keystone terminology and an array of individual to population-level examples. The term ‘equal’ has different meanings; however, it is relative to the level of the biological hierarchy being discussed and the structural/functional context of the species.

On a population level, species may be unequal due to adaptations, abundances, feeding preferences, behavioral traits, growth rates, and other factors. On a community level, they can be unequal because of their food web configuration context. However, the fact that a keystone species might be the first receiver of an external perturbation is of no special significance since all nodes along the path jointly carry the impact to the end node. The node does not control anything; it only passes on an impact from an environmental driver. All nodes along an operating path subsequently change, causing more important consequences for the whole food web’s structure and function than the keystone merely as a conduit. Sometimes keystones are associated with specific pathways, such as trophic cascades and escalades (Lane 2017a, b).

In addition, Power et al. (1996) concluded: “An increasing body of evidence suggests that keystone species are context dependent. Keystone species are not necessarily dominant controlling agents in all parts of their range but instead play keystone roles only under certain conditions…Nevertheless, ecologists still lack the empirical basis needed to detect, interpret, and predict general patterns in the occurrence of keystone species or to apply the concept for management”. This is probably true. Robert Paine knew the rocky intertidal zone so well that he was one of the first investigators to understand ecological context-dependency in a profound, biologically meaningful way. For example, he reported that in his Piaster spp. communities in the rocky intertidal zone, starfish function as a keystone predator in some communities but not others. Thus, their functional roles were context-dependent. Several other authors besides Paine have discussed the importance of context-dependent differences in the roles of species, especially those labelled as keystones in their food webs (Jonsson et al., 2015; Salomon et al., 2010; Bruno & O’Connor, 2005; Power et al., 1996), and these authors have hypothesized diverse explanations of how species are context-dependent. Barrios-O’Neill et al. (2017) reported that “keystone functionality can be transient concerning environmental context” and that non-consumptive in that behavioral aspects of food web interactions can also influence the role of potential keystones. Estrada (2011) concluded that “…there is no universal way of detecting keystone species in the food web, although several measures for their a priori identification have been proposed.”

Because assigning a ‘control’ function to every known keystone species has been problematic, as is the prevalence of context-dependent food webs, it is not surprising that no list of invariant keystone characteristics has ever been created. Many believe the keystone concept has been applied too rigidly, based on one food web structure, one keystone species, and one driver, when in nature, all three are highly dynamic and pluralistic. For example, Mills et al. (1993) concluded the concept has been used too narrowly: “…Neither the science of ecology nor the protection of biodiversity is advanced by continuing to label certain species as keystone... Suppose they [investigators] abandon the keystone-species concept and the rigid structure it imposes on species interactions. In that case, investigators are less likely to assume that interactions or their strengths in distributions are constant in space and time”.

In addition to the keystone concept, other authors have described individual species as exceptional in their food webs based on their position in the network configuration. When ecologists label a species important in a network, they refer to the structural-functional role that species serves within the rest of its network structure or topology, a branch of mathematics that studies the deformations of geometrical objects due to stretching without breaking. For example, a sphere can become an ellipsoid without fracturing. Too often, ‘keystoneness’ described above is attributed to properties of the species (such as large body size, superior ability to catch prey, or effective fear generator in the landscape) rather than its relational network context. In network theory, various calculations are used to determine node importance. The first type is related to network centrality, and clustering measures are calculated based on the node’s centrality, specifically its degree (the number of links it has to other nodes). For example, Jonsson et al. (2015), Jordán et al. (2008), and Estrada (2007) have concluded that highly connected species are most important. Loop Analysis does not support this view, nor do machine networks. A television set with all nodes connected is nonfunctional. Evolution selects for self-organization with discrete qualitative structure, not merely increases in nodes, links, and nodes/link (Cottam & Ranson, 2017; Lane, 2018a).

The second type of network measure is percolation, which involves not just a structural measure. However, there are changes in the quality of the nodes, such as a virus infecting some nodes but not others, or information influencing only certain nodes in a social network. Percolation ‘experiments’ in the field, lab, or by computer can be conducted in which a series of nodes are removed sequentially, sometimes randomly. The resultant network is analyzed to determine how much robustness (~functional integrity) it has lost and whether a ‘percolation threshold’ has been crossed, leading to fragmentation, cascading failures, and network breakdown. Thus, percolation theory deals with network robustness, an area developed in statistical physics and mathematics.

Both Newman (2010) and Barabási (2016) described the concept and its application in network studies. For example, Jonsson et al. (2015) studied eleven species traits of species randomly removed from 100 randomly generated food webs of fifty species each to determine if there were secondary extinctions. They found that some large-bodied, high-trophic-level species, such as secondary predators, could be important in maintaining the integrity of food web structure. However, species with other traits, such as predator stress capacity or structural sensitivity, could be the most important in more degraded food webs. They concluded that food web structure and extinction risk are causally related and that species’ roles in their food webs change with food web degradation. This work also bears upon the previous subsection in that it confirms keystone status whenever applicable. It is not so much associated with the uniqueness of the phenotypic traits or prowess of a species, but instead with the context dependency that the whole food web confers on a species in its network configuration. This explains many negative field observations about potential keystones that fail to assume that role. Piravenan et al. (2013) used topological centrality to develop a percolation centrality measure in epidemic networks, in which, in addition to topological position, nodes could be characterized by their susceptibility to a virus. Complex systems exude endless surprises. Essentially, the context-dependent notion means that the entire network is continually important, and ignoring the context dependency of the entire food web carries some risk.

Two Species Systems

While single species can add constraints and opportunities to a food web, so can two-species systems. Predator-prey interactions are often fundamental to discussions of ecological control in food webs. They represent some of the most common direct interactions, as exploitation competition and mutualism often involve a third node with indirect linkages. Predator-prey interactions form the bulk of the loops in food webs and, as such, are worthy of some attention here. The predator is most often ascribed the ‘controller’ role (C1) in the relationship since the number of predators decreases the number of prey designated as the ‘controlee’ (C2). Density change is usually the control process (C3) resulting from lowered prey abundances (C4). Tiselius and Møller (2017) concluded, “predation is the strongest force acting on populations, and it is therefore not surprising that the most visible controlling factor in food webs is the presence or absence of predators”. Since all species consume prey or other resources, these two conclusions are questionable and not supported by Loop Analysis.

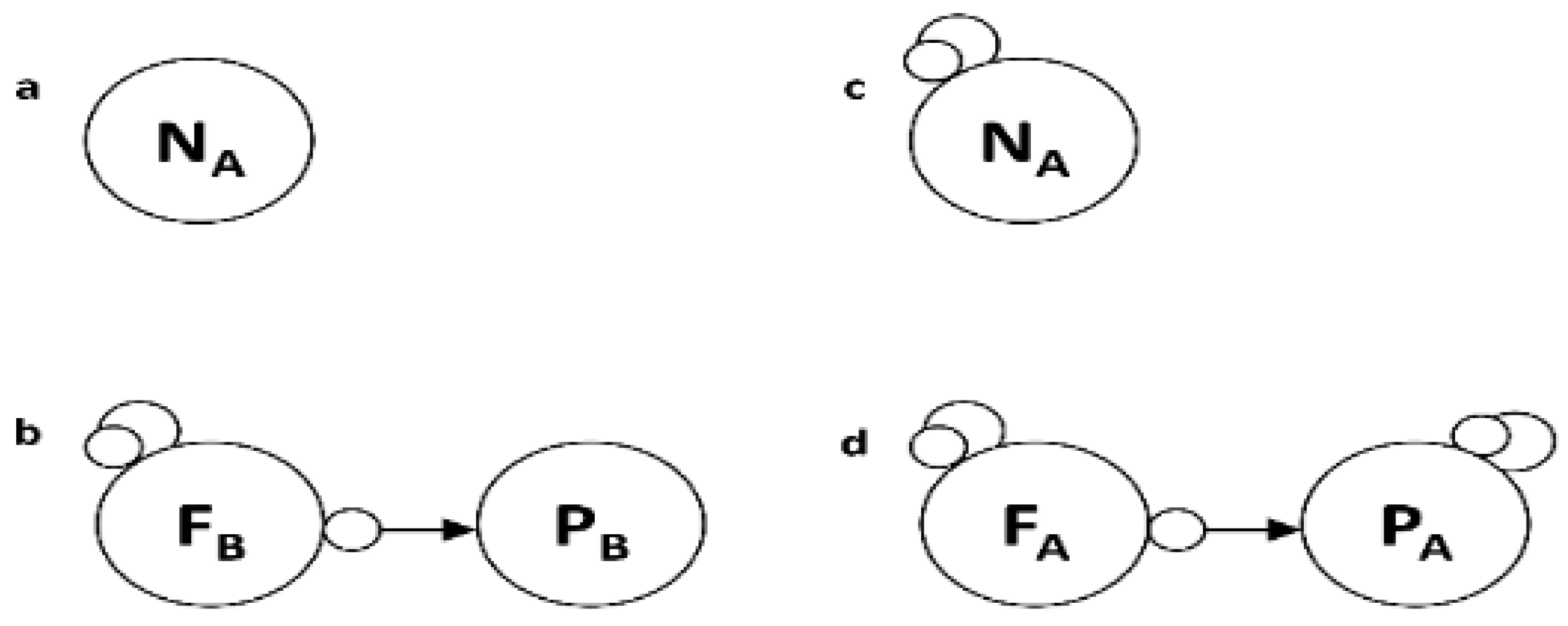

Many food web representations draw a line from the prey to the predator with an arrowhead on the latter. The relationship, however, is two-way and asymmetric in Loop Analysis: the prey is harmed (-) represented by a circlehead touching the prey, and the predator benefits (+) shown by an arrowhead touching the predator (

Figure 1b,d.). Thus, the relationship cannot be described as two isolated links or a simple one-way relationship. Instead, it is a closed feedback loop of length two, which cycles causality continuously in multiple locations throughout a food web. Being short negative feedback loops (+ times - = -), each predator-prey interaction imbues the food web with stability. Low densities of prey, however, can cause the predators to decrease in numbers. In the latter instance, should we refer to the prey as a controller and the predator as a controlee? Feedback causality is endless, and for a loop, the starting node is arbitrary and entirely lost in the system's evolutionary history.

Predator-prey systems are renowned for their oscillatory behavior and the limit cycles they generate. Hastings (2001) reported that “a spatially coupled predator-prey system is an example of a cyclic ecological system where coexistence depends on oscillations. Transient dynamics of models with no stable persistent solutions are shown to be a reasonable explanation of persistence over ecological timescales…”. This same predator prey interaction, however, can produce -, +, or zero correlations when occurring in a paired oscillatory time series (Arditi & Ginzburg, 2012; Loeuille & Loreau, 2004), and additional counterintuitive results can occur when these species pairs are embedded in a food web, which always occurs in nature.

Although time lags are inevitable and ubiquitous, they are often unspecified in control discussions. Garay-Narváez and Ramos-Jiliberto (2009) and Dambacher and Ramos-Jiliberto (2007) have provided several insightful examples of two-species loop models of predator-prey systems and complications of food chains involving coupled predator-prey loop models. Many things in nature come in pairs, but control does not operate on only two nodes in a network. Furthermore, indirect pathways can easily dominate the effects of a direct two-node interaction (Higashi and Patten, 1989; Patten and Higashi 1991). Thus, without a detailed study, it is usually impossible to conclude that any predator is ‘controlling’ its prey, given how the control process is usually defined (Hall, Stanford, and Haver, 1992). As Hall (2020) pointed out that even for one of the most famous examples of oscillatory predator-prey behavior in the hare-lynx populations in the Canadian Hudson Bay fur trade study, investigators: (1) used data from spatially discrete populations, (2) used harvested fur pelts as a surrogate for field abundances, (3) revealed that sometimes peak abundances of lynx preceded those of hares, which was nonsensical since hares do not consume lynx, and (4) hares often exhibit oscillatory cycles when lynx are absent such as in insular environments, which is consistent with the inherent population dynamics of a single species discussed in the previous section (Dambacher, et al., 1999). Arditi and Ginzburg (2012) and Ginzburg and Colyvan (2004) have also provided detailed and sophisticated discussions of predator-prey dynamics, including an alternative explanation of the traditional lynx-hare case study. Hall (2020) did not generally give much credence to predator-prey control, concluding: “Every organism is controlled by the environmental conditions of their micro or macro location. He believed instead that there are energy gains and costs along environmental gradients (Hall et al., 1992; Hall, 2020). Nevertheless, predators a priori are almost always labelled as controllers in ecological systems.

Johannessen (2014) questioned whether predators even have a deleterious effect on their prey. He hypothesized that predator-prey relationships between herbivores and phytoplankton exhibited synergism in the lower levels of food webs in Norwegian waters. He defined this as a relationship that helped both species. Thus, although predators have a direct negative effect on their prey by consuming them, they facilitate the recycling of nutrients that benefit the prey’s longer-term interest in sustaining its production. He suggested this gave the grazed algae a competitive advantage. He also hypothesized that the synergy would promote ecosystem resilience and a temporal dependency or autocorrelation that would help dampen the adverse effects of physical and chemical drivers. Thus, the prey would ‘give up’ a portion of their production to their predators for a stable nutrient supply. This is like an ecological tax that all species must pay to benefit from food web participation. Johannessen (2014) also proposed a synergistic relationship between zooplankton and their planktivorous predators.

Species have many things to do to survive. There is no rule or reason why they can only do one thing at a time, especially considering each species has a multitude of functions necessary for its survival and reproduction. Perhaps, not all predation is solely damaging to the prey. For example, in cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis, their coexistence involves many complicated positive and negative aspects (Furla, 2005; Lane, 2018a). A sophisticated cost-benefit analysis would be required to determine the net effect. In summary, one and two-species systems can be complicated and surprising, often requiring expansion to a larger set of nodes and links for complete understanding. The notion of control can be elusive. Now, let us consider extending the two-link predator-prey dynamics to sets of these interactions embedded in food chains.

Food Chains

Are Trophic Cascades and Escalades Controllers?

Food chains consisting of coupled predator-prey pairs constitute the dominant pathways that occur in food webs. Hessen and Kaardvedt (2014) concluded, “one of the most successful and intuitive terms in ecology is that of the food chain”. Barbier and Loreau (2018) stated that “the food chain has become one of the most widely studied [concepts] in empirical and theoretical ecology”. However, they admitted “its fundamental predictions have a checkered history of success outside of textbook examples”. Food chains have no side linkages. A food chain has only two pathways: down a trophic cascade or up a trophic escalade (Lane, 2017a). One cannot travel sideways, despite the preponderance of marine omnivores that create side links and web-like structures. Furthermore, these pathways lack operative feedback, which is typically considered essential for control (Lissack, 2021). How could a straight line of causality in any sense, be a control system? Bossier et al. (2020) applied Lane’s (2017a,b) trophic cascade concepts to the Black Sea ecosystem with an integrated food web model. Despite the trophic cascade concept being a simple linear pathway, it has been enthusiastically imbued with almost magical explanatory and predictive capabilities (Ripple et al., 2016; Terborgh & Estes, 2010; Piovia-Scott et al., 2017). Reiners et al. (2017) found that bottom-up/top-down control was a frequent choice of respondents when asked to identify the most useful ecological concepts of the last 100 years.

Although trophic cascades have been defined in numerous ways (Ripple et al., 2016), the definition used here derives from evaluating causal pathways in Loop Analysis models. It is modified from Lane (2017a): “A trophic cascade is all or part of an operating pathway, including at least three adjacent nodes and two links, starting with a node at or near the top of the food web and ending with a node at or near the bottom, with all the links on the pathway representing predator-prey and/or consumer-resource (trophic) interactions that produce a distinctive checkerboard pattern of changes in the standing crops [nutrient concentrations and species abundances] of the path nodes”. In contrast, “causal pathways that begin at or near the bottom of a food web are termed trophic escalades if they include at least three adjacent path nodes and two trophic links” (Lane, 2017a). Escalades usually exhibit singular patterns of all increases or all decreases in the food chain nodes if the top trophic level is self-damped. If there is no self-damping at the top, then zero values in standing crops alternate levels of the food chain, beginning with the zero at the lowest level for a model with an even number of trophic levels and a sign (+ or -) for an odd number of trophic levels. In nature, this type of pattern is less evident than the checkerboard pattern, but it occurs six times more frequently than trophic cascades in marine plankton communities (Lane, 2017a, b). The size and duration of the effects in both trophic cascades and trophic escalades are often left unspecified in most definitions and reports of field and laboratory studies.

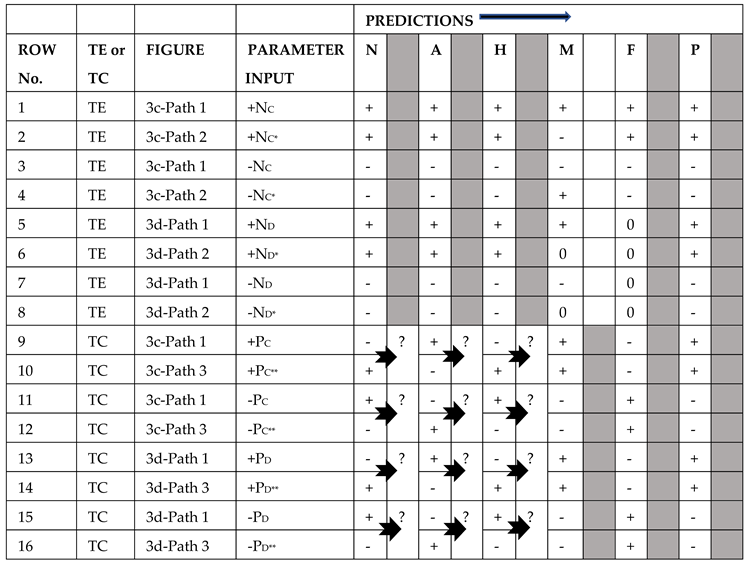

Table 1 summarizes the possible patterns. Lane (2017a, b) discussed the history of trophic cascade/trophic escalade concepts and identified several invalid assumptions that permeate the trophic literature, as did Leroux and Loreau (2015).

Because trophic cascades and trophic escalades exhibit discernible patterns in the field and laboratory, they have been elevated to special importance in marine and other food webs. Nature abounds in patterns. Mobus and Kalton (2015) defined pattern as “a set of components that stand in an organizational relationship with one another from one instant of a system to another”. Both trophic cascades and escalades produce identifiable patterns in the field and laboratory. The human brain is designed for pattern recognition, and over evolutionary time, our survival has depended upon this capability in a natural world brimming with dangers. Patterns are the shiny objects that capture our attention, and ecologists frequently identify patterns at the individual, population, and community levels, which advance our understanding of the natural world. For example, Cury (2018) detected four patterns during his career: optimal environmental window, extended homing strategy, wasp-waist ecosystems, and ‘one third’ for marine birds. He concluded these patterns were both accurate and valuable. Winemiller and Layman (2005) distinguished four types of food web patterns (Christmas tree, onion, spiderweb, and Internet). Ecologists become more excited about trophic cascade and escalade patterns than the stripes on a fish or the coiling of a snail shell, because these trophic patterns occur across the food web, albeit on only a single pathway, and can be identified in nature. They hope these patterns will explain ecosystem-level causality that is urgently needed as the environmental crisis deepens. Unfortunately, this hope is ill-founded since even if a pattern in nature is recognizable or its formation is explainable, it does not guarantee its usefulness or importance. Many patterns are merely by-products of other processes such as (1) opposing chemical gradients in development that cause stripe patterns in coral reef fish and individual agent-based actions that produce fish schools like cellular automata (Wolfram, 2002), or (2) mathematical artifacts and constraints such as fractals, symmetries, tessellations, and Fibonacci sequences (Ball, 1999; Solé & Goodwin, 2000; Bejan & Zane, 2012). Link et al. (2015) identified hockey-stick and sigmoidal patterns of cumulative biomass and production in 120 marine ecosystems and used these patterns to identify ecosystems undergoing perturbation. The authors described these patterns as ‘emergent’, but it seems much more likely that they were patterns of collective properties.

Given the inherent heterarchical structure of marine food chains and food webs, trophic cascades and escalade patterns are inevitable. Every food web of three or more levels has the potential for a classic checkerboard top-down trophic cascade pattern as defined here and a bottom-up trophic escalade. They are common, almost at the level of the mathematical artifact. Chains of predator-prey loops can only produce the canonical checkerboard pattern of alternating plus and minus values when the driver enters at the top. Thus, these patterns originate because food web conceptualization a priori generates their existence, and trophic cascade/trophic escalades can exist in nature when drivers initiate them. However, not all claims of trophic cascade and escalade occurrences are undoubtedly valid. Ecologists often claim they are unique and essential (Terborgh et al., 2010; Estes et al., 2011), but this is not true regarding ecosystem dynamics.

Trophic cascades, and to a lesser extent, trophic escalades, have often been the primary focus in ecological control theory (Harvey et al., 2012). Heath et al. (2014) contrasted two ways control has been used to conceptualize top-down phenomena: (1) “the role of a varying factor in exerting an influence on other components of the system”…(2) “mechanisms or processes within food webs, specifically self-limitation processes or density dependence phenomena, which lead to alteration in the per capita rate of change in a population as a direct function of its abundance” as discussed here in terms of one-species autoregulation. They concluded that lumping disparate control processes under one ‘control umbrella’ is confusing. Trophic control notions have also expanded the original concept of simple machine control, as trophic cascades are now viewed as controlling entire food webs. The assumption that trophic control exists as a simple mechanism via a single pathway is often taken for granted, with little to no attempt at explanation or validation (Leroux & Loreau, 2015; Lassalle et al., 2012). For example, Mittelbach (2012) concluded, “Trophic cascades are evidence of the importance of top-down control in many ecosystems and may highlight the consequences of losing top predators from systems worldwide”. Although trophic cascades can also be equally activated when the environment improves for a top predator, rather than just when a predator is declining, these phenomena are rarely mentioned as initiating trophic cascades. Examples include a fishing fleet ceasing operations, a rise in a desirable temperature, or some other environmental factor that improves the life of a top predator. When predators decline to low levels, they are simply unable to be important initiators of trophic cascades.

Frank et al. (2005) equated control with the occurrence of trophic cascades, thus making control a necessary but unspecified aspect of their somewhat circular definition: “Trophic cascades are defined by (i) top-down control of community structure by predators, and (ii) conspicuous indirect effects two or more links from the primary one”. Their definition also includes the notion of control at the food web/ecosystem level, yet, interestingly, no one discusses what happens with the nodes not on a pathway or how a trophic cascade changes the overall network configuration. How can this be a food web-wide phenomenon when only a few components of a few trophic levels are included in the control process (C3), and similarly, the result (C4) consists of only changes in the densities of the same few nodes? In addition, what is the controller (C1): the first node on the path, such as a keystone predator, or the whole pathway, and what is the controlee (C2): just the pathway's nodes after the first one, or the total food web?

Although ecologists have generally favored trophic cascades over trophic escalades as the primary controllers of ecosystems, this has been a long-standing controversy. Atkinson et al. (2014) noted, “the role of the top-down and bottom-up control on the food web is hotly debated for various reasons. They are scale dependent and sensitive to precisely how we define the evidence for top-down control.” Getz et al. (2003) attempted to resolve the controversy using Metabolic Control Analysis, yielding mixed and conditional results, while acknowledging numerous limitations. Marine ecosystems are more sensitive to perturbation at lower trophic levels than at higher ones, a phenomenon that has been observed in marine systems for more than 100 years in various locations, using different datasets, approaches, and conceptualizations. For example, Harvey et al. (2012) reported a preponderance of bottom-up effects in a 20-year data set for Puget Sound, although they also noted some top-down ones. They concluded that if some bottom-up processes dominate, management efforts with top-level predators may be less successful. Could it be otherwise, given the nutrient-poor nature of most marine environments? How could the animals exist if nutrients were not available from the lower levels to nourish top predators, if not from the bottom up, given the drivers occurring at the bottom of the marine food webs? Bottom-up ‘control’ is less frequently discussed, except under the amorphous topics of nutrient limitation and climate change. So-called controllers for trophic escalades would occur at the lowest trophic node (nutrients) compared to the apex predators for trophic cascades.

Many authors have proposed that trophic cascade/escalade-induced patterns could be theoretically significant and pragmatically relevant for ecosystem management. For example, Frank et al. (2005) claimed “the existence of top-down control of ecosystem structure (implied by trophic cascades) creates opportunities for the understanding and manipulation/management of exploited ecosystems, because exploitation is generally focused on top predators”. Often, a trophic cascade is suggested as the controller. The causal logic of their argument can be briefly stated as: (1) an external driving force makes the world worse or better for a top predator, which in turn (2) initiates a trophic cascade, which then (3) controls the abundance/diversity patterns of lower food web components, and thus, the food web. (4) Furthermore, since ecologists understand this form of control, they can manage food webs. Although authors ascribe a ‘control’ function a priori inherent in trophic cascades and escalades (Frank et al., 2005, 2006), they are only non-autonomous pathways defined by the patterns they produce. They operate solely based on how non-path nodes are configured, as shown in Loop Analysis (see below). While admitting that “trophic control is difficult to quantify, largely because it cannot be directly observed”, these papers did not define the term, but said it could be inferred since “strong positive correlations indicate resource control, as both populations are driven by factors regulating productivity, and strong negative correlations indicate consumer control, as predators suppress the abundance of their prey”, however, when trophic escalades produce alternating zeros, correlations are weak not strong. Here, the authors use trophic control as a population-level term to describe the direct relationship between two adjacent predator-prey nodes in a food web and then extrapolate this to a higher level of the hierarchy: the food web, without knowing how the food web is configured. This five-part logic is flawed.

Whereas apex predators impact or affect ecosystems, these terms are not synonyms for control. Loeuille and Loreau (2004) distinguished control and effect as follows: “control indicates the factor (resource or predator) that limits the abundance or biomass of a trophic level; effect describes the consequence of perturbing the system at either the top or the bottom”. (Note that the control they define is at the population-level as a predator consuming a prey, which is the routine job of every predator.) There has been a notion of false equivalency among control and effect (impact) in that if the driver initiates an effect (+ or -) via a significant change in the standing crop of the node it enters, sometimes this is seen as equivalent to ‘strong control’ or sometimes the initially impacted node is considered to be a controller. Change is only an impact or effect initiated by a driver. For example, changes in species abundances occur ubiquitously in food webs and are associated with all pathways and complementary processes operating simultaneously, as well as with internal processes within particular nodes. Thus, no single species or path can control a whole food web.

In addition, trophic cascades and escalades make up only a tiny percentage of all causal pathways in food webs. However, all other operating pathways function precisely as trophic cascades and escalades by causing changes in abundance and turnover rates in the participating path nodes, beginning with a first node that has either been externally perturbed or altered internally. Thus, trophic cascades and escalades are not ‘special’ to an ecosystem; they are only important to investigators because their recognizable patterns provide a veneer of ecosystem-level understanding. Initially, trophic cascade and escalades were viewed hopefully as an ecological Rosetta Stone (Estes, Burdin, and Doak, 2016; Garvey and Whiles (2016), to understand ecosystem causality, but this was based upon the invalid premise that a single causal pathway could control the whole network and not the more valid reverse notion: the overall system embedding a causal pathway determines whether it is even operational or not.

A Comparative Loop Analysis of Six Food Chains

Relatively small loop diagrams can support the points made in this section.

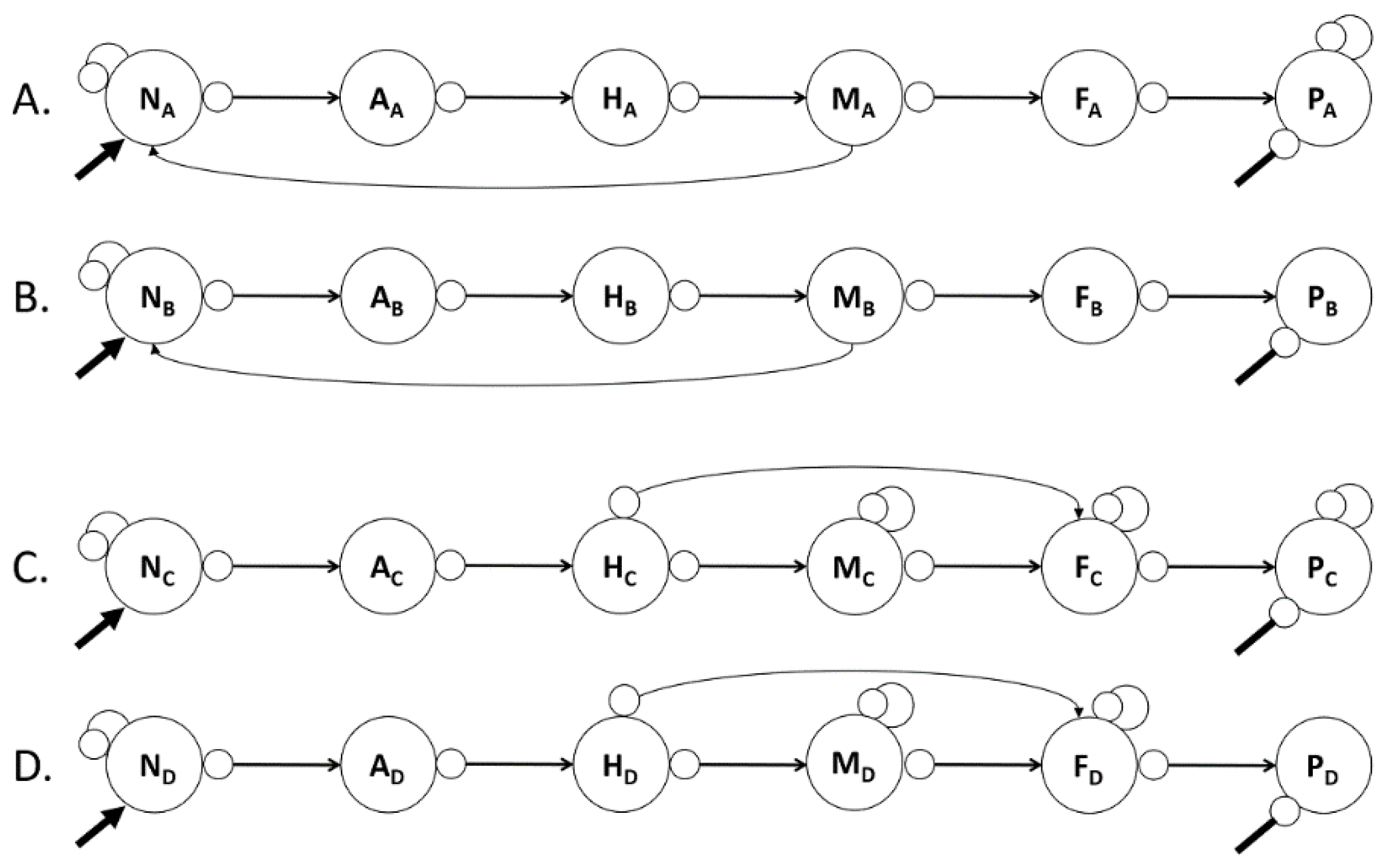

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 compare variations in predictions of abundances for alternative configurations of a six-node loop model of a pelagic marine food chain. These models also provide additional information on the Loop Analysis methodology and its applications.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the total of all pathways, complements, and drivers operating simultaneously in a single food web, which produces changes in species abundances and nutrient concentrations. A trophic escalade or cascade does not produce more potent effects than other pathways simply because its pattern is recognizable. Heath et al. (2014) analysed the mathematics of trophic cascade relationships and reported results consistent with those of Loop Analysis.

Figure 2 illustrates two food chains, 2a and 2b, each with six nodes. Two external drivers simultaneously impact both food chains. First, nutrient enrichment at the bottom of the food chain is a positive driver to the nutrient node (see the more prominent, disconnected line with an arrowhead), which initiates a trophic escalade. Second, a similar disconnected line ending with a circle-head, which initiates a trophic cascade, illustrates an adverse effect on the top predator. Figures 2a and 2b represent the same food chain, except that the top predator PA is self-damped, while P

B is not.

Table 3 illustrates that trophic escalades and trophic cascades exhibit distinct yet different patterns of changes in the abundances of food chain nodes (Lane, 2017a). Trophic cascades always produce a checkerboard pattern, although whether the first node at the top of the food web changes positively or negatively relates to the sign of the driver (Rows 5 and 6). The checkerboard pattern is inevitable mathematically because of the algebraic multiplication of negative signs down the food chain from P to N. Multiplying an odd number of negative signs gives a negative product, whereas multiplying an even number of negative signs results in a positive product.

In Rows 1-4 of

Table 3, patterns for trophic escalades are illustrated. Nutrient enrichment is indicated in the diagram as a + driver. However, predictions for a negative input are also given. As with trophic cascades, the initial nutrient change depends on the sign of the driver. If it is negative, all nodes up the food chain will also be negative, and conversely, if it is positive, all nodes up the food chain will change positively. Zeros frequently appear in trophic escalade predictions because the final node may not be self-damped, causing some of the upward pathways to lack valid complements as the causal effect proceeds up the food chain to the top predator, as illustrated in

Figure 2b and

Table 3: Rows 3 and 4. Most investigators focus on trophic cascades compared to trophic escalades, even though the latter is many times more common than the former. This may be partially explained by the common occurrence of alternating zero predictions for trophic escalades, which makes trophic escalade identification more challenging in field data (

Table 3, Rows 3 and 4), as well as a lack of focus on the ecological theory of trophic escalades. Trophic escalades do not produce alternating checkerboard sign patterns but can exhibit single signs (+ or -) with or without intervening zeros (Rows 1-4). There can also be all-zero predictions if the nutrient node is buffered by a satellite node, for example, a toxic phytoplankton species that takes up nutrients but is not consumed by animals in the food chain (Lane & Levins, 1977). The satellite itself, however, will have a nonzero prediction.

Figure 3 and

Table 4 and

Table 5 illustrate how complicated notions of ecological control can become even in a food chain by adding only one or two side links and feedbacks involving more than three nodes. For example, in Figures 3a and 3b, nitrogen excretion is added as a single side link and trophic cascade predictions below the constriction and escalade predictions above it occur similar to those of wasp waist food webs without relying on any controller constricted bottom-top pathways as per common explanations (Bakun, 2006; Fauchald et al., 2011; Atkinson et al., 2014; Hunt & McKinnell, 2006; Cury, et al. 2000). Thus, small forage fish such as the anchovy, sardine, caplin, and herring are designated as controllers in the middle of the food web. Nodes involved with the wasp-waist phenomenon are usually small forage fish that affect predator populations above them and prey populations below. Hunt & McKinnell (2006) hypothesized that the wasp-waist species influence energy flows mainly in upwelling zones, where initially larger predators control the forage fish, which in turn escape top-down control and overwhelm their predators (predator pit) (Bakun, 2006). Atkinson et al. (2014) termed this ‘middle-out control’.

Nitrogen excretion of meso-predator to the nutrient pool and the top predator is self-damped.

Nitrogen excretion of meso-predator to the nutrient pool and the top predator is not self-damped.

Herbivores have two predators, and the top predator is self-damped.

Herbivores have two predators, and the top predator is not self-damped.

In Figures 3a and 3b, the driver to the piscivore (P) is negative (

Table 4: Rows 5 and 7).

Table 3 also gives the predictions for a positive driver to P (Rows 6 and 8), which is not illustrated. A negative driver typically indicates exploitative fishing or an external predator not represented in the loop model. P would not usually spend its whole life cycle under negative external forcing unless extinction is the endpoint of its existence. For example, temperature may change favourably with a positive effect on P. Depending on whether the driver increases or decreases P, the rest of the changes in the food chain nodes alternate with the nutrient level. Usually, zeros do not appear in trophic cascade predictions. An exception would occur when there was an undamped second predator on F (or some lower node), which acted as a satellite node with only one input and one output to the rest of the network (not illustrated). This second predator would buffer F (or a lower node) and all nodes below it, producing zero predictions down the food chain since any downward pathway would leave the second predator (or competitor in the case of algae) as part of an invalid complement.

Once the directed changes are predicted, it is possible to make qualitative correlation matrices for each row of predictions and identify overall patterns of change. For example, in

Table 4, for trophic escalade predictions, both Row 1 and Row 2 nodes are all positively correlated. In Rows 3 and 4, A, M, and P are positively correlated with each other, but not correlated with N, H, and F. Rows 5-8 for trophic cascades all exhibit negative correlations for adjacent pairs of nodes and positive correlations for pairs of nodes connected by an intervening node. Thus, negative and positive correlations occur down a food chain, while only positive correlations occur up a food chain, producing trophic cascades and trophic escalades, respectively.

In Figures 3a and 3b, the same six-node food chain is complicated by a nitrogen excretion link by the meso-predator and an additional prey species for F (small fish). Predictions for trophic escalades (the first four rows of

Table 4) remain unchanged from their counterparts in

Figure 2. As the pathway proceeds upwards from nutrient to meso-predator, it cannot return to N via the M-N link because this would violate the definition of a pathway. The pathway can only proceed to F and P. Thus, in this model, the excretion of nitrogen by M does not affect the overall dynamics of the system when considering trophic escalades. It is different, however, for the trophic cascade patterns in the bottom eight rows of

Table 4, where two pathways operate simultaneously (Rows 5-12). P, F, and M predictions remain the same, but once the downward pathway (P-F-M) reaches M, it can branch into two pathways. Path 1 follows the food chain, as shown in

Figure 2, and Path 2 originates from M-N-A-H. When this second pathway ends at A, the change in A is zero because H, the only complement node, is not in a loop, thus making Path 2 to algae (A) non-operative (Rows 6, 8, 10, 12). Other authors have frequently observed trophic cascades stopping at the zooplankton level. A strong meso-predator (M) excretion link would explain this observation most simply, although other hypotheses are possible. Figures 3a and 3b note that the nitrogen excretion link also produces a four-node, one-way, positive loop (N-A-H-M-N), which is destabilizing.

With the introduction of the strong nitrogen excretion link operating in Path 2 in Figures 3a and 3b, the loop predictions essentially bifurcate into a classic trophic cascade checkerboard pattern for the top three nodes of the food web. In contrast, the bottom three nodes exhibit a classic trophic escalade pattern, essentially a discontinuity in predictions. This bifurcated pattern, consisting of one-half trophic cascade and one-half trophic escalade, results in a wasp-waist pattern in pelagic ecosystems, as mentioned earlier. Thus, a typical wasp-waist pattern can be generated by a single metabolic process depicted as a side link in Figures 3a and 3b, not by assuming a middle species is a ‘controller’. In a food chain, however, every node is a species or a trophic level, like a wasp-waist node. One node embedded in a food chain cannot be a constrictor of the pathway effects. Furthermore, how long a wasp-waist configuration could endure in the pelagic zone over the annual cycle is unclear.

Figures 3c and 3d show a new predator-prey link representing the consumption of herbivores (H

C and H

D) by small fish (F

C and F

D, respectively). There are also self-damping loops on the meso-predator M

C, F

C, M

D, and F

D. In

Figure 3d, P

D without self-damping becomes a satellite node to F

D, producing zero predictions for M and F (Table X: Rows 6 and 8) in the trophic escalade calculations for Path 2. When there is more than one pathway between two nodes, as in Rows 1 and 2, and predictions are not the same since M is increasing in Row 1 and decreasing in Row 2, question marks are entered in

Table 4 to indicate ambiguity.

In food chains with no side links (Figures 2a and 2b), all pathways beginning at the top or bottom are either trophic cascades or trophic escalades, provided they have a minimum of three nodes. There are no other options, but with one or two side links, the classic trophic cascade/trophic escalade patterns can quickly blur (

Table 5: Rows 9-16) as food chains transition to food webs. These patterns have an inherent fragility. Trophic cascades or trophic escalades may not even be discernible in real-world food webs. However, food webs can exhibit other kinds of strong operating pathways, such as those initiated by drivers to the middle nodes, which are not diagrammed here.

Trophic cascades/trophic escalades have been frequently regarded as relevant to management, using the logic that trophic pathways can reveal ecosystem-level causality needed to analyze anthropogenic and natural stressors in marine ecosystems and associated socio-economic systems, acting as controllers. The hope has been that since trophic cascades and trophic escalades can traverse all trophic levels; they potentially permit us to observe singular patterns at the ecosystem level, however, Arditi and Ginzburg (2012) pointed out that “studies of food chains are on the edge of two domains of ecology: population and community ecology. The properties of food chains are determined by their basic link, which is the interaction between two species: a consumer and its resource, or a predator and its prey. Studying this basic chain link is a part of population ecology, while the more complex food webs, consisting of many food chains, belong to community ecology”. Thus, food chains are at best a weak concept at the ecosystem level. Individually, they are only fragile, isolated threads of potential causality into the future because they are so transitory and isolated. They are often extracted from their ecosystems in a reductionist manner by severing all other links with the whole network. Many of the claims advocating for trophic cascade/escalades as the ‘silver bullet’ for understanding marine ecosystems and making management operational (Frank et al. 2005, 2006) appear to be unrealistic and exaggerated. Hessen and Kaardeveld (2014) concluded that trophic cascades are useless for food web management.

In summary, the trophic cascade/trophic escalades theory has been overly reductionist with too many simplistic assumptions, especially regarding ecological control. Suppose trophic cascade/trophic escalades were functional control ‘levers’ as some authors have claimed. In that case, it seems there would be some tangible proof of their management efficacy by now, more than fifty years after the Green World Hypothesis and initial trophic cascade publications, and even longer from initial anecdotal field observations of their existence. Pershing et al (2015) made a similar observation. Many trophic cascade/trophic escalade control claims have never been tested theoretically or empirically. Barbier and Loreau (2018) also called for meaningful integration of these areas. Loop Analysis might be a good way to do this. Now we turn to a consideration of how food webs are regulated through a set of constraints.

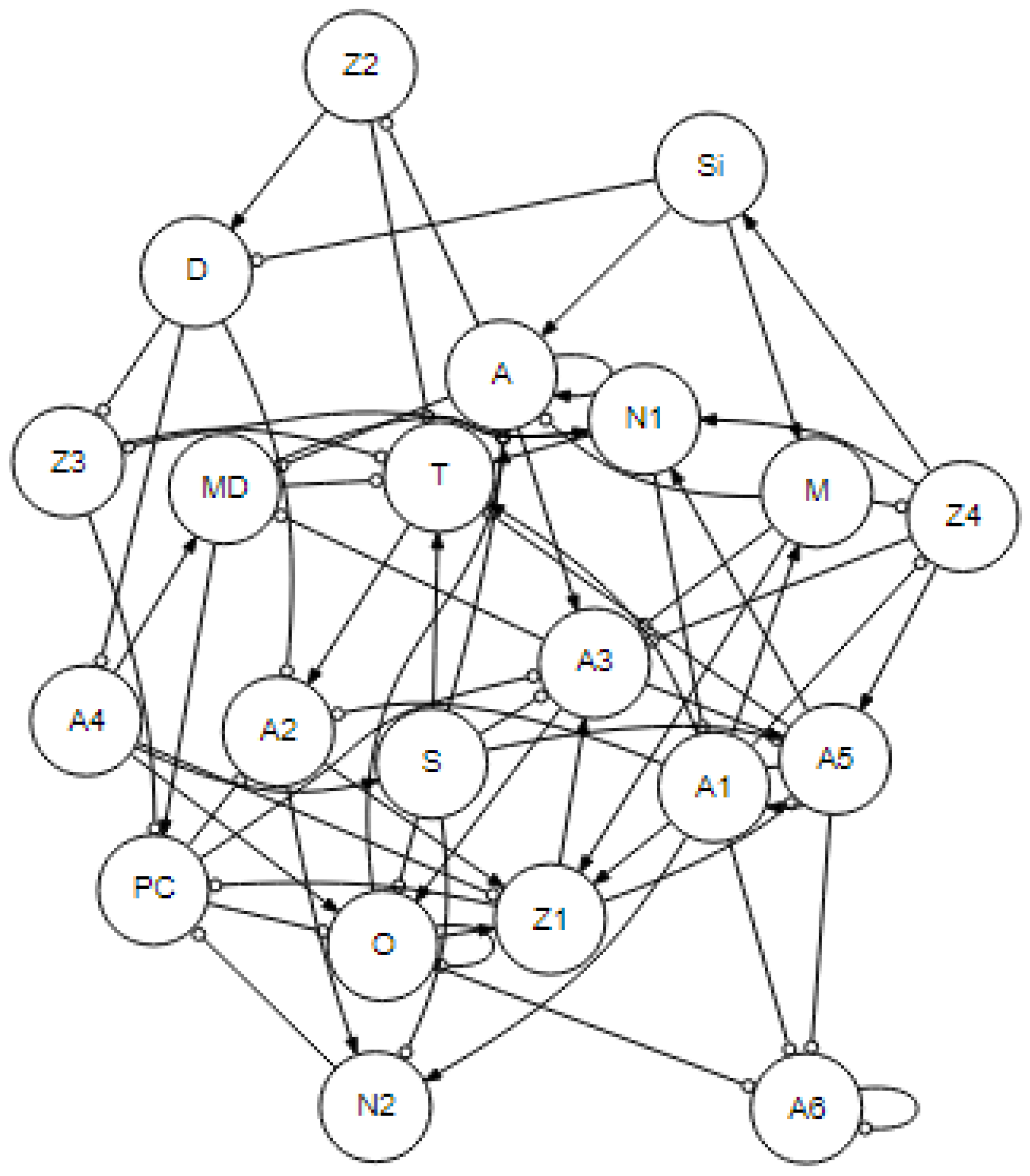

Food Webs

This section is organized into five parts: (1) Control Versus Constraint in Ecological Networks’ gives a brief summary of research and thinking in this area; (2) Network Context: The Ecosystem as a Complex Ecosystem Chimera provides a conceptual view on how plankton ecosystems function and evolve, which is necessary to understand how they self-organize and employ constraints; (3) ‘Self-organization and Constraint: Ecological Skeletons in Marine Food Webs illustrate the specific network structure used as the basis to understand control and constraint in this paper. Constraint is a function of a system’s organization, and it is important to determine the underlying network arrangement before constraint can be proposed. (4) Network Motifs: Comparison of Biologically Reasonable Versus Random Food Webs compares the results from network analysis in non-ecological areas of systems biology to ecological networks; and (5) Some Benefits of Using Loop Analysis for Identifying Internal Constraints of Food Webs lists reasons why Type II LA is a valuable tool to study constraints in ecological networks.

Control Versus Constraint in Networks

Much of the thinking in this paper directly or indirectly aligns with the work of Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela (1980) on autopoietic, autonomous systems rooted in 2nd Order Cybernetics using structural coupling and conceptual causal network models, Robert Rosen’s (1991, 2000, 2012) Relational Biology for self-organizing, anticipatory systems with Graph Theory and Category Theory models, Richard Levins’ (1973, 1975) Loop Analysis with its focus on ecological feedback in signed digraphs, and Bernard Patten’s Environs Theory (Nielsen, et al., 2020; Patten et al., 2011) using transactional (input-output) carbon flow networks in Systems Ecology. All four approaches depend on conceptualizing networks. While the four network representations differ from one another, the most notable shared feature is their pattern of node interactions or links, which are essentially both functional and relational. As Hofmeyer (2008) explained, “Nothing in an organism makes sense except in the light of the functional context”; the same is true for ecosystems.

Since a network’s structural arrangement is a set of functional links, in a fundamental way, function transcends structure, as Robert Rosen (1991, 2000) always asserted. The network structure is both functional and relational, contrary to the traditional biological belief that structure comes first, followed by function second. Additionally, a node located in a network has much more functionality than an isolated node or a small set of nodes in a linear array, such as a 2-species interaction or food chain pathway without feedback. Networks, primarily those rich in feedback loops, provide system functions that are impossible to anticipate by knowing only their nodes. Feedback is a central feature in control as well as many types of constraints (Leonard, 2021).

Emergence can also be an outcome. We are just beginning to understand the emergent properties that constrained networks produce, such as consciousness in the human brain and ‘aliveness’ in life itself. It is not easy to imagine emergence to occur separately from a network. Finding emergence in ecological networks is an ongoing process, and the use of unrealistic network models has hindered its success. Perhaps, the entire nature of reality, including space at the quantum and cosmic levels, consists of relational networks (Rovelli, 2014, 2018). Although Carlo Rovelli, as a theoretical physicist, has not worked at the ecological level, if his loop quantum gravity interpretation proves true through experimental verification, it is unlikely to exclude any systems between his two extreme levels of interest. Due to the power of networks, reductionism, despite its previous dominance in science, will never be sufficient to understand complex living systems, such as ecosystem chimeras or environs networks. Richard Levins' favorite quote from Hegel, “the truth is the whole,” suggests that the ultimate reality of living systems can be found in their wholeness as vibrant, dynamic, ever-changing networks. We cannot understand the whole by examining a collection of parts while severing the links that create organization and meaning for a system. The essence of an ecosystem lies in its interconnectedness, not its stuff.

Control

Much of our understanding of the theory of control and its machine applications has emerged from first-order cybernetics, which was developed in the mid-20th century by Norbert Wiener (1948, 1961, 2nd ed.), Ross Ashby (1952, 1956), and others. These early cyberneticists sought to compare control and communication within and between machines and living organisms. Much of control system theory in engineering comes from these initial contributions and concepts. Although second-order and third-order cybernetics have emerged, many of the early concepts persist in current applications to living systems. For example, Cosentino and Bates (2019) provided a detailed description of how engineering control notions can be used in biology, including bifurcations, hysteretic switches, oscillations, and some feedback functionalities. Raginsky (2023) explained, however, that first-order cybernetics is inadequate for understanding autonomous living systems, which motivated the development of second-order cybernetics and the pioneering work of Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana on autopoietic systems (Varela, 2025; Maturana & Varela, 1980). While cybernetic thinking has been helpful in biology and ecology in seeking similarities between living systems and machines, and will continue to be for the foreseeable future, the application of cybernetic concepts to living systems does not render them isomorphic to machines. There are significant differences between the two types of systems, which necessitate a thorough analysis and understanding (Patten, 1959; Patten & Odum, 1981; Whipple et al., 2014).

Nielsen et al. (2020) concluded that “Ecologists from the beginning of the subject have always been concerned with issues of control-allogenic or autogenic at the physiological, population, community, and ecosystem levels of organization.” Some authors have recognized that the term ‘control’ is too absolute and oversimplified for food webs and have substituted terms like regulation (Leroux & Loreau, 2015). However, this distinction has not always been helpful because the term has been used too frequently as a synonym for control. For example, Heath et al. (2014) used ‘regulation’ to distinguish density-dependent phenomena like self-shading or cannibalism. The authors’ notion of ‘regulation’, however, was limited to a scattering of density-dependent processes, often small negative self-loops, throughout a food web, rather than the entire network configuration with its total set of feedback loops and subgraph structures. Barbier and Loreau (2018) also emphasized the importance of density dependence in trophic dynamic models. However, even taken together, a few small balancing loops are insufficient to characterize the independent, self-organized existence of a food web.

The frequent use of the term ‘control’ in food web studies, particularly in the reductionist context of the machine metaphor (Henning & Scarfe, 2013), is also problematic for such complex systems. Rosen (1991) explained: “Physics as we know it today is entirely the science of mechanism, and mechanisms, as I argue, are very special as material systems. Biology involves a class of systems more general than mechanisms. The relative positions of physics and biology have become interchanged; rather than physics being general and biology special, it becomes more the other way around” (Rosen, 1991). The current tectonic shift in scientific focus from simple, closed, mechanical, context-independent systems to the current one on complex, open, context-dependent, self-organized, anticipatory living systems is essentially a paradigm shift in the sense of Kuhn (1970). Bongard and Levin (2021) argue that recent developments in biotechnology, AI, and synthetic biology have rendered the machine metaphor considerably outdated. There is growing emphasis today on making machines life-like rather than reducing organisms to machine simplicity. For example, physics and engineering now look to biology for design inspiration, such as creating solar panels that resemble leaves and prostheses that resemble human limbs.

While we continue to rely on the simple linear causality and reductionist analysis to understand nature, how can closed systems inform open ones? Physics has struggled to consider open systems, yet we have relied on physics and its mechanisms to serve as conceptual scientific guides, even to the extent of determining what questions can be asked and what concepts and processes can be applied to biological systems (Lane, 2024b). A brief review of the contrasts among the various current interpretations of quantum theory and the associated controversies that have raged unabated for over a hundred years corroborates that physics does not possess all truths for all systems, not even its own. Many aspects of the living world, such as function, autopoiesis, cognition, anticipation, causal closure, efficient cause, and final cause or purpose, are not tolerated in the closed realm of forces, momentum, and particles, but are inherent in self-organized, autonomous biological systems. This irrational embrace of physical simplicity fundamentally belies our experience of living systems, which consists of a networked reality characterized by feedback and feedforward causality, among other types, intricately constrained within time and space in a context-dependent manner.

If food webs are incompatible with the machine metaphor, conclusions about their control using this conceptualization are also dubious. Taken to the logical extreme, this would mean that every predator that consumes prey, or a herbivore that eats a plant, ‘controls’ its prey or food resource, thus making all biotic nodes controllers. For food webs, how is it decided what % of the standing crop of prey must be consumed by predators to achieve a ‘control effect’? What about dwindling prey populations controlling their predators? This diffuse notion of control is not useful. While most species in a food web are consumers of others, the term ‘control’ is too strong, negative, and misleading. Terms like impact, effect, influence, increase, and decrease are more appropriate when discussing simple predation. At a minimum, if the term ‘control’ is used at any level of the biological hierarchy, a few questions should be asked: (1) What level of the biological hierarchy is of central interest? (2) What is the controller (C1), the controlee (C2), the process (C3), and the result (C4)? Moreover, control over what? If the result, C4, is genuine control at the ecosystem level, then this requires clear documentation.

Living systems, such as food webs, are self-organizing and autopoietic, meaning they create themselves. They are autonomous, and their organization is causally closed (Rosen, 1991, 2000); thus, to understand how they maintain their networked organization, realize the functions necessary for life, unbroken over eons of time since the first prokaryotes existed on earth over 4.5 billion years ago (Coale et al, 2024), requires a deeper examination beyond a two node predator-prey interaction or a linear food chain path. It is more than machine control. To achieve this, we need to understand how constraints, especially self-generated constraints, are formed and function within an ecological network. Currently, we may only understand ecosystem constraints ‘through a glass darkly’, it is a ‘work in progress’, but an important one if we are to deal with a deteriorating planet successfully.

Constraints

Several definitions of constraints for systems have been proposed. Joslyn (2001) defined constraint as “any restriction or limitation, for example, a boundary or set of initial conditions in dynamical systems so that relational constraints reduce the state space populated in a mathematical description.” Juarerro (2023) defined a constraint as “a structure-producing causal influence that determines what part of the phase space a system will occupy out of many possible trajectories it might initiate. The cause does not have to be a force of A acting on B, but can include patterns, especially habituated ones, boundaries, and organizational structures.” A constraint is not only a piece of matter like the proverbial brick wall or a pipe carrying water, but a network of linkages. One such ‘organizational structure’ is the plankton community lattice (see below). Biological constraints are context-dependent and are not just random forces acting on particles. “Constraints are like riverbanks; they do not push the water, but they guide it where it flows” (Juarrero, 2023). A system’s network accomplishes this by framing the possible pathways through which energy, matter, and information flow within a system, ensuring that flow is impossible in other pathways, and thus shaping its phase space of potentialities. This immediate space is akin to Kauffman’s (2019) expanded notion of the ‘adjacent possible’, and Lane’s (1986, 2017) concept of the abstract meso-universe (see below). Life is only a minute subset of its potentialities, just like the set of known chemical molecules is a tiny subset of the chemical networks that could exist.

Ecosystem constraints themselves can be highly dissimilar. Some are material, while others are virtual, and most are interconnected to attain successful biological functionality, ecosystem identity, and evolutionary persistence. Juarrero (2023) distinguished among constitutional, enabling, internal, governing, dynamic (temporal), external, and contextual constraints. Patten et al. (2011) provided an even more exhaustive list of constraints based on the assumption that constraints and system organization are inextricably linked. They also included species as being constraints because each has a range of functionalities, so that “The species list in an ecosystem or region represents an established set of biological infrastructure constraints that enable both function and change”. With so many structural and functional features involved in ecosystem constraints, it might be easier to ask, ‘What cannot be a constraint?’.

Biological systems, such as ecosystems, have evolved creatively to employ a set of constraints that ecologists have not always had the imagination to discover. Patten et al. (2011) concluded that “constraints, as a category, are understudied in ecology, poorly understood in ecological phenomenology, and (our hypothesis) comprise a ubiquitous organizing force in nature…Navigating existing constraints and contributing to the establishment of more of them are, in fact, the central work of living nature.” These authors advanced the unconventional hypothesis that although constraints are often viewed negatively as impeding or inhibiting systems, “the driver of organization is constraint”, which is primarily based upon providing requisite ecosystem functions to ensure a positive outcome. We believe that Patten et al.’s (2011) conclusion is correct.

Juarrero (2023) agreed with Patten et al. (2011) that while constraints limit degrees of freedom operative in a system, they were essential to the maintenance of a system’s self-organization and coherence. Coherence relates to the identity of a system that, while ever changing, retains its robust ‘selfness’. Living systems continually turnover and replenish the atoms that constitute them while maintaining their identity. Juarrero (2023) concluded, " Each aspect of a differentiated coherent dynamic embodies and enacts a distinct set of constrained interdependencies with its own logic of emergent properties and powers. Coherent parts-to-whole and whole-to-parts relations induced by constraints persist in the face of change. Their patterns are metastable, realized as vectors of complex attractors; they define ecosystems,...” Sacco et al., (2025) have even gone beyond self-organization in living systems to conclude that biological networks also represent cognition at non-ecological levels in the biological hierarchy (Lyon, 2025). Although their conclusion is intriguing and supported by their experimental data, it is beyond the goal of this paper to explore how ecosystems process information and may have cognition. These are open questions to be explored in a subsequent paper, but if true, would also involve constraints.

A significant portion of our current understanding of control and constraint in biological systems originates from the molecular level, utilizing reductionistic approaches that can be characterized as bottom-up, involving gene regulatory and protein interaction networks (Pezzulo & Levin, 2016). These authors reasoned that there has been much less work on top-down approaches, in part due to the misguided fear of invoking teleology and the taboo subject of vitalism. They argued that more top-down models are needed to understand the regulation and goal-seeking of whole systems, like Type II Loop Models used below. The authors provide several examples of properties observed in top-down models, including feedback control, optimality principles, least action and least effort principles, the virtual governor effect, attractor theory, and the free energy principle. Pezzulo and Levin (2016) defined a virtual governor as “an emergent relational property or phenomenon of the entire system,” which serves as one knob for entrainment. They suggest, “Much as the boiler is best regulated by policies that manage pressure and temperature, and not the individual velocities of each of the gas molecules, biological systems may be best amenable to models that include information structures (organ shape, size, topological arrangements, and complex anatomical metrics) not defined at the molecular cellular level, but nevertheless serving as the most causally potent ‘knobs” regulating the large-scale outcomes”. What could these knobs be in ecosystems?

How constrained are food webs? This is a difficult question to answer definitively, but it seems likely that constraint is extensive. Palsson (2015) identified four categories of constraint that are modified here for plankton food webs: (1) physical-chemical laws and constants, (2) spatial-topological-temporal limitations, (3) environmental factors and their spatial-temporal patterns, and (4) self-imposed biological constraints. Although these four categories are not mutually exclusive and often overlap, they provide a framework for the subsequent discussion. We have moved the topological constraints to Category 4 for ease of explanation, as most of that discussion is essentially about the network topology of loop models we use to delineate network structure. Patten et al (2011) provided an even finer taxonomy of constraints based upon epistemic and ontic categories. However, there is not enough space here to explore them systematically in the plankton networks below.

- (1)

Physical-Chemical Laws and Constants: The experience of existence includes many types of external constraints, limitations, boundaries, and other influences related to physical-chemical laws and constants like the nature of matter, fundamental forces such as gravity, electromagnetism, strong and weak nuclear forces; universal constants like the speed of light, the gravitational constant, the proton to electron mass constant, the cosmological constant etc., and laws of nature such as the laws of thermodynamics, law of gravitation, and law of mass action. For example, the speed of light is seen as a constraint on momentum. Living systems, as combinations of matter and energy, are part of the physical universe; however, they are proportionally a small percentage of all matter and energy. Nevertheless, living systems are subject to the same physical and chemical laws as nonliving matter. For this paper, we assume these external, universe-wide constraints and laws provide a backdrop or landscape for life. Patten et al. (2011) detailed the roles of several physical-chemical constraints operative in ecosystems. Additionally, Patten’s Environs Theory provides a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness and wholeness of ecosystems, encompassing their physical, chemical, and biological features.

- (2)