1. Introduction

Multidimensional poverty represents a structural challenge that disproportionately affects rural communities, particularly small-scale agricultural producers in developing regions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This approach recognizes that poverty is not limited to income deprivation but involves simultaneous deficits in areas such as education, health, housing, and working conditions, generating persistent inequalities that hinder sustainable development [

5,

6]. Consequently, the uncertainty and magnitude of environmental change have compounded longstanding issues of marginalization and multidimensional poverty among rural farmers [

7].

Therefore, the first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda calls on countries to eradicate poverty in all its forms and dimensions, advocating for more comprehensive measurement methodologies such as the Multidimensional Poverty Index [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In this context, Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSS), such as fair trade certification, have been promoted as instruments to improve the living conditions of smallholder farmers. These certifications aim not only to ensure fairer prices and access to international markets but also to foster sustainable agricultural practices, social cohesion, and equity [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In the case of Honduras, a country highly dependent on the agricultural sector and characterized by lagging rural social indicators—it is essential to assess whether fair trade certifications contribute meaningfully to reducing poverty from a multidimensional perspective [

17,

18]. This need for measurement becomes even more relevant considering coffee's strategic importance in the national economy. Honduras ranks as the seventh-largest coffee producer globally, exporting to 64 countries and generating more than USD 1.39 billion in annual foreign exchange. As of September 2023, annual production reached 6.9 million 46-kg bags of coffee, 57% of which were certified or specialty coffees. Germany is the leading importer of Honduran coffee (21% of total exports), followed by Belgium (9.6%) and Italy (5.2%) [

19]. This context underscores the importance of analyzing whether the added value of certifications translates into tangible improvements in the living conditions of small-scale producers.

This analysis gains depth when examining the structure of the Honduran coffee sector. According to data from the Honduran Coffee Institute (IHCAFE) [

19], the sector comprises more than 120,000 farming families, spread across 210 municipalities in 15 departments. Of these, 92% are smallholders with coffee plots smaller than 3.5 hectares. Regarding export destinations, 55% of Honduran coffee goes to Europe, 33% to North America, 6% to Asia, and the remaining 6% to other global markets. Honduras stands out as the largest coffee producer in Central America, the third in the Americas, and the seventh largest exporter worldwide.

Nevertheless, despite the growth of certification initiatives and their role in the export dynamic, there remains a scarcity of empirical studies in Honduras that evaluate their effectiveness beyond income particularly in dimensions such as education, health, housing, and employment. This gap in literature limits evidence-based policymaking and hinders decision-making by producers, cooperation agencies, and governments alike.

To analyze the impact of certification, it is necessary to address the core concepts underpinning this study, structured into three key dimensions: (1) the concept and functioning of fair trade; (2) cooperatives and voluntary sustainability certification in the coffee sector; and (3) the multidimensional poverty approach as an indicator of well-being in rural communities.

1.1. Fair Trade and Its Impact on Small-Scale Producers

Fair trade is an alternative model of international exchange that seeks to transform global trade relations through principles of equity, sustainability, and the empowerment of producers [

20,

21,

22]. The World Fair Trade Organization [

23] defines it as an approach based on dialogue, transparency, and respect, aimed at achieving greater equity in global trade. According to [

24], fair trade emerged as a civil society response to socially regulate international markets, particularly in the agricultural sector.

One of its main objectives is to reduce poverty through solidarity-based exchange mechanisms, which has motivated the adoption of certification systems. Studies such as [

16] highlight that fair trade certification has had positive effects on the income and living conditions of cooperative members, although these benefits do not always extend to non-organized agricultural workers.

The growth of fair trade has been linked to increasing social and environmental awareness among consumers, who are willing to pay higher prices for certified products [

25,

26,

27]. This trend is further reinforced by the growing demand for transparency and sustainability in supply chains [

28,

29].

However, doubts remain about its actual impact. Some studies find that certification does not always result in significant improvements compared to non-certified producers [

17,

30]. Moreover, [

31] points out persistent inequalities in the coffee value chain, where most of the added value is captured by actors in the Global North, while producing countries receive only a minimal share.

In Latin America, agricultural cooperatives, especially in the coffee sector, have been the main vehicles for implementing fair trade. These organizations facilitate access to differentiated markets, promote technical training, and enable producers to negotiate under better conditions [

32,

33]. Their collective structure also strengthens resilience in the face of market volatility [

34,

35]. However, their effectiveness depends on their ability to adapt to local conditions and to include the most vulnerable producers [

36,

37]. Overall, the literature suggests that fair trade can contribute to rural development and poverty reduction, provided that organizational structures are strengthened and inclusive outreach is expanded.

1.2. Cooperatives and Voluntary Sustainability Certification in the Coffee Sector

In the context of fair trade and agricultural sustainability, coffee cooperatives—composed primarily of small-scale producers—have assumed a strategic role in promoting rural development. Through collective production and associative work, these organizations strengthen the productive and commercial capacities of their members while facilitating access to Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSS) such as Fairtrade, UTZ, Rainforest Alliance, and 4C [

38,

39,

40]

VSS have gained prominence as global governance mechanisms that promote economic, social, and environmental incentives for producers who comply with international standards [

41,

42,

43]. Fairtrade certification offers benefits such as guaranteed minimum prices, community development premiums, and access to premium markets, which can translate into higher incomes and improved social services [

44,

45,

46].

Despite these advances, the literature also highlights significant limitations: high certification costs, structural barriers, and inequalities in value distribution within supply chains [

47,

48,

49]. These tensions are especially relevant in regions such as Honduras, where cooperatives have played a key role in the adoption of these certifications. Although they have improved access to fairer markets and encouraged sustainable practices [

50,

51], their effects on reducing multidimensional poverty are not always sustainable or equitable, which calls for a deeper contextual analysis to evaluate their true effectiveness [

52]

1.3. Multidimensional Poverty: Its Dimensions and Relation to the Sustainable Development Goals

The approach on multidimensional poverty acknowledges that poverty is not limited to the lack of income but encompasses multiple deprivations that affect quality of life, such as education, health, housing, and access to decent employment [

53,

54]. This framework allows for a more comprehensive characterization of poverty conditions and provides an empirical basis for designing more effective public policies. In line with this vision, the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and adopted by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), considers various simultaneous deprivations experienced by households [

55]. Its purpose is to capture poverty in broader terms than income alone, including deprivation in fundamental capabilities. Multiple studies have demonstrated its utility for analyzing structural conditions in rural areas as well as vulnerability to climate change [

56,

57,

58]

These dimensions are also aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, thus providing both a normative and operational framework for analysis.

SDG 4, which aims to ensure inclusive and quality education, is directly linked to overcoming structural deficits in human capital. In agricultural contexts, low levels of schooling, illiteracy, and poor school attendance hinder both the adoption of new technologies and participation in local development processes. This situation has been widely documented in rural areas of Pakistan, Nigeria, and China, where educational deprivation reinforces cycles of poverty [

59,

60,

61]. In Honduras, the MPI includes indicators such as school attendance, average years of schooling, and functional illiteracy [

62]

Regarding SDG 3, which relates to health and well-being, limitations in access to safe drinking water, basic sanitation, and medical services are critical determinants of vulnerability in rural areas. These conditions affect quality of life, increase the burden of preventable diseases, and reduce household productivity. Recent studies in Asian contexts have confirmed that such deficits disproportionately affect poor rural households [

63,

64]. The Honduran MPI incorporates variables in this dimension such as the type of cooking fuel used, availability of safe water, and access to adequate sanitation [

62].

The link between employment and poverty is clearly reflected in SDG 8, which promotes decent work and inclusive economic growth. In rural areas, informality, underemployment, and lack of social protection limit social mobility opportunities and perpetuate economic insecurity. The persistence of child labor reinforces this intergenerational dynamic of exclusion. International literature has documented these conditions across various regions, highlighting their structural impact [

54,

65,

66,

67]. In Honduras, the MPI includes indicators such as underemployment, lack of social security, and the presence of child labor [

62].

SDG 11, which focuses on sustainable and inclusive communities, highlights housing precarity as a core component of rural poverty. Overcrowding, poor-quality construction materials, and lack of services such as electricity or legal ownership hinder access to basic conditions of well-being. According to various studies, these deficiencies not only affect physical and mental health but also limit the educational and economic trajectories of households [

57,

68]. The Honduran MPI addresses this dimension through variables such as floor, roof, and wall materials, overcrowding, and property ownership [

62]

Finally, various international experiences have shown that these deprivations can be addressed in an integrated manner. Climate-smart agroforestry has had positive impacts on employment, health, and food security [

69], while in Mediterranean regions, the MPI has been used as a diagnostic tool to guide agricultural development and water management projects with a territorial approach [

70]. These initiatives suggest that frameworks such as the SDGs and the MPI not only enable the measurement of deprivation but also support the development of public policies that are more coherent with rural realities and structural challenges.

Table 1.

IPM Honduras: Dimensions and indicators.

Table 1.

IPM Honduras: Dimensions and indicators.

| Health |

Education |

Work |

Home |

| Access to adequate water systems (HE1) |

Years of education for household members aged 15-49 (E1) |

Social Security (W1) |

Access to electricity (HO1) |

| Adequate sanitation access (HE2) |

School attendance (E2) |

Underemployment (W2) |

Floor material (HO2) |

| Type of fuel for cooking (HE3) |

Illiteracy (E3) |

Child labor (W3) |

Roof material (HO3) |

| |

|

|

Wall material (HO4) |

| |

|

|

Overcrowding (HO5) |

| |

|

|

Heritage collection (HO6) |

Numerous studies have identified a positive correlation between the implementation of sustainability certifications and the reduction of multidimensional poverty in rural contexts [

63,

71]. However, it has been noted that such benefits do not always result in significant improvements in health, education, or housing, indicating that certification alone may not be sufficient [

72]

In this regard, [

30] found that Fairtrade certification has contributed positively to agricultural performance, pricing, and the financial stability of producers. Nevertheless, its impact on multidimensional poverty varies depending on factors such as education level, access to credit, and institutional environment [

16,

73].

In the Honduran context, the effectiveness of fair trade certification as a poverty reduction strategy depends on the availability of infrastructure, financing, and government support [

17,

19]. Therefore, it becomes necessary to analyze specifically how and to what extent these certifications influence the quality of life of small-scale agricultural producers

Given this context, the present research aims to evaluate the effect of fair trade certification on multidimensional poverty among smallholder farmers. To this end, the following research question is posed:

Research Question:

What is the effect of fair trade certification on multidimensional poverty among small-scale agricultural producers?

Null Hypothesis (H₀):

There is no significant difference in levels of multidimensional poverty between certified and non-certified small-scale agricultural producers.

Alternative Hypothesis (H₁):

Certified small-scale agricultural producers exhibit significantly lower levels of multidimensional poverty compared to their non-certified counterparts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Data Collection

According to the National Supervisory Council of Cooperatives of Honduras (CONSUCOOP) [

74], as of May 2024, the country has 192 registered coffee cooperatives, reflecting the significance of the cooperative model in the organization and commercialization of Honduran coffee. Likewise, the Honduran Coordinator of Small Fair Trade Producers (CHPP-Fairtrade) [

75] reports that, as of February 2025, there are 72 Honduran organizations certified under Fair Trade, 37 of which are coffee cooperatives officially registered.

2.2. Sampling Design and Analytical Techniques

Data collection was carried out between December 2024 and March 2025 using the Google Forms platform to facilitate participation by coffee producers. The sample consisted of 419 coffee producers selected from 16 cooperatives located across various regions of Honduras: eastern, western, southern, and central areas. Among these cooperatives, 8 were Fair Trade certified and 8 were not, allowing for a balanced comparison between the two groups (see

Table 2). In each cooperative, 25 farmers were surveyed, ensuring an equitable distribution of the sample. This sampling strategy provided adequate representation of producers' conditions across different coffee-growing zones, ensuring the validity and reliability of the data collected.

The analysis techniques were developed in three phases: 1) Univariate Descriptive Analysis, 2) Non-parametric Analysis using the Mann–Whitney U Test, y 3) Non-parametric Analysis using the Chi-Square Test

2.2.1. Phase 1: Univariate Descriptive Analysis

In the first stage, a univariate descriptive analysis was conducted on 15 ordinal items covering the dimensions of multidimensional poverty: health (HE1–HE3), education (E1–E3), employment (W1–W3), and housing (HO1–HO6). The objective was to statistically characterize the individual behavior of each variable by analyzing distributional properties such as shape, dispersion, and central tendency.

Although the variables are ordinal, classical descriptive statistics were used as a complement to the non-parametric approach applied in later phases. This type of analysis is helpful when ordinal levels are numerous and uniformly spaced.

For each item, the following statistics were calculated:

Minimum and maximum values to observe the empirical range.

Arithmetic mean and variance as traditional measures of central tendency and dispersion.

Skewness, to evaluate the symmetry of the distribution.

Kurtosis, as an indicator of the concentration of data around the distribution center.

These values helped identify response bias, significant asymmetries, or atypical clustering. Summary tables with key statistics per item were also created as exploratory groundwork for the hypothesis tests conducted in the following phases.

2.2.2. Phase 2: Mann–Whitney U Test

In the second phase, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare the distribution of ordinal poverty items between groups defined by the categorical variable CERT (certification status). This test is appropriate for comparing two independent groups when the dependent variables are ordinal or do not follow a normal distribution, as in this study.

Each of the 15 items (HE1–HE3, E1–E3, W1–W3, HO1–HO6) was tested based on certification status, with a significance level of α = 0.05. The U statistics and the corresponding two-tailed p-value were calculated for each test, indicating whether statistically significant differences existed in the response distributions by CERT group.

The null hypothesis in each case assumed that the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of the corresponding items were equal across groups. Rejection of the null hypothesis indicated a significant difference in response patterns. These test results provided a robust approximation of structural differences between certification groups in relation to the various poverty dimensions analyzed.

2.2.3. Phase 3: Chi-Square Test

In the third phase, the Chi-Square (χ²) test of independence was used to assess the existence of significant associations between the ordinal items of multidimensional poverty and the categorical variable CERT (certification status). Since the χ² test requires categorical data, the ordinal variables were recoded into grouped levels based on frequency and empirical relevance, while preserving interpretive validity.

Contingency tables were created for each of the 15 items, cross-tabulated with CERT levels. The χ² statistic, corresponding degrees of freedom, and p-values were calculated using a critical level of α = 0.05. Rejection of the null hypothesis indicated a significant relationship between the item and certification status, while failure to reject it suggested statistical independence.

This phase complemented the previous one by detecting patterns of association between response categories and certification group membership, thus enriching the understanding of the phenomenon from a categorical and relational perspective.

2.3. Analyzed Cooperatives

The cooperatives selected for the study are distributed across different coffee-growing regions of Honduras: central, western, eastern, and southern.

Table 3 presents the participating cooperatives, both certified and non-certified, along with their respective departments and regions.

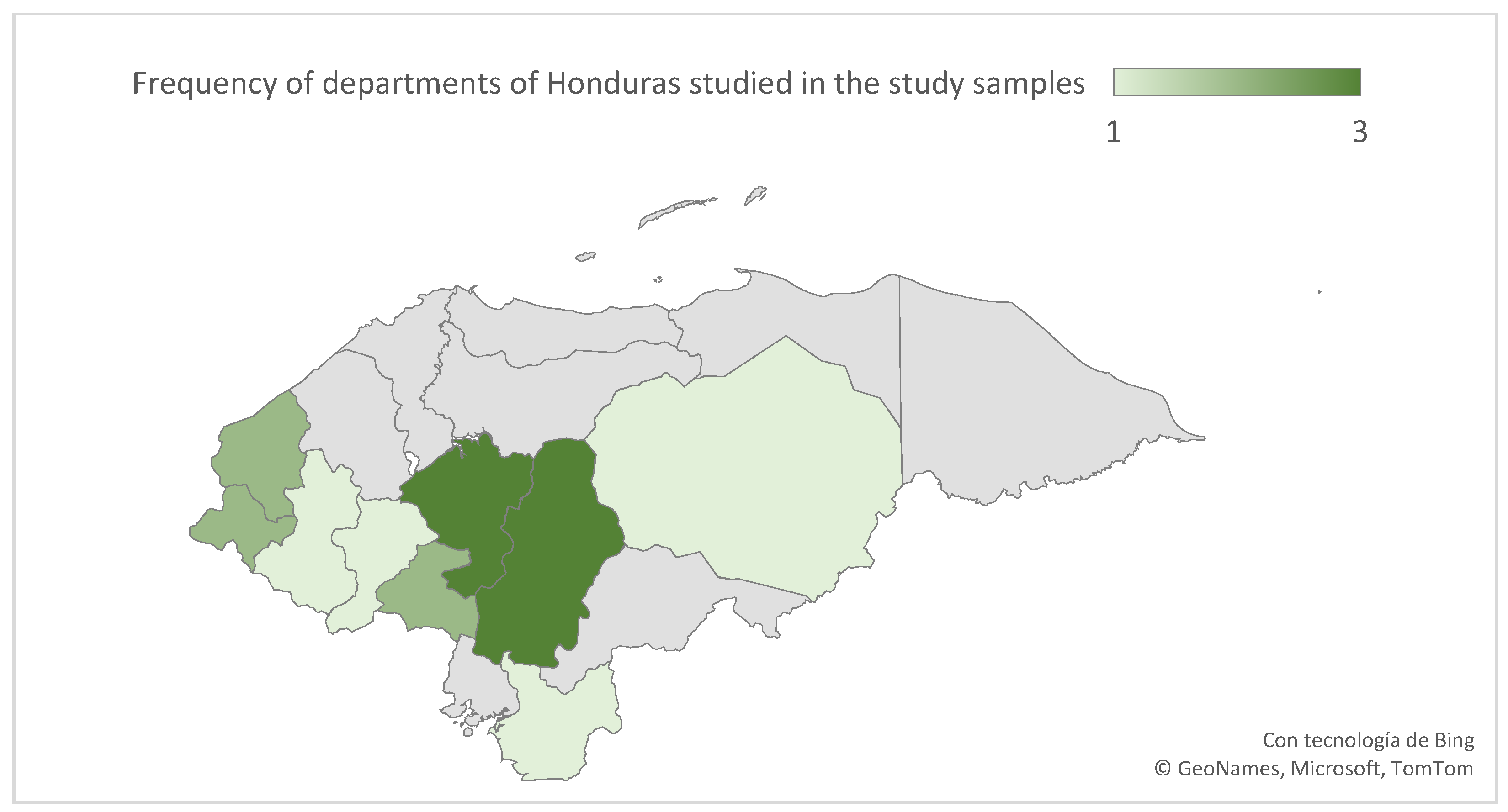

In addition, the sample is distributed across nine of the 15 coffee-producing departments in Honduras: Francisco Morazán, Copán, Olancho, Choluteca, Intibucá, Ocotepeque, La Paz, Comayagua, and Lempira (

Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Univariate Descriptive Analysis

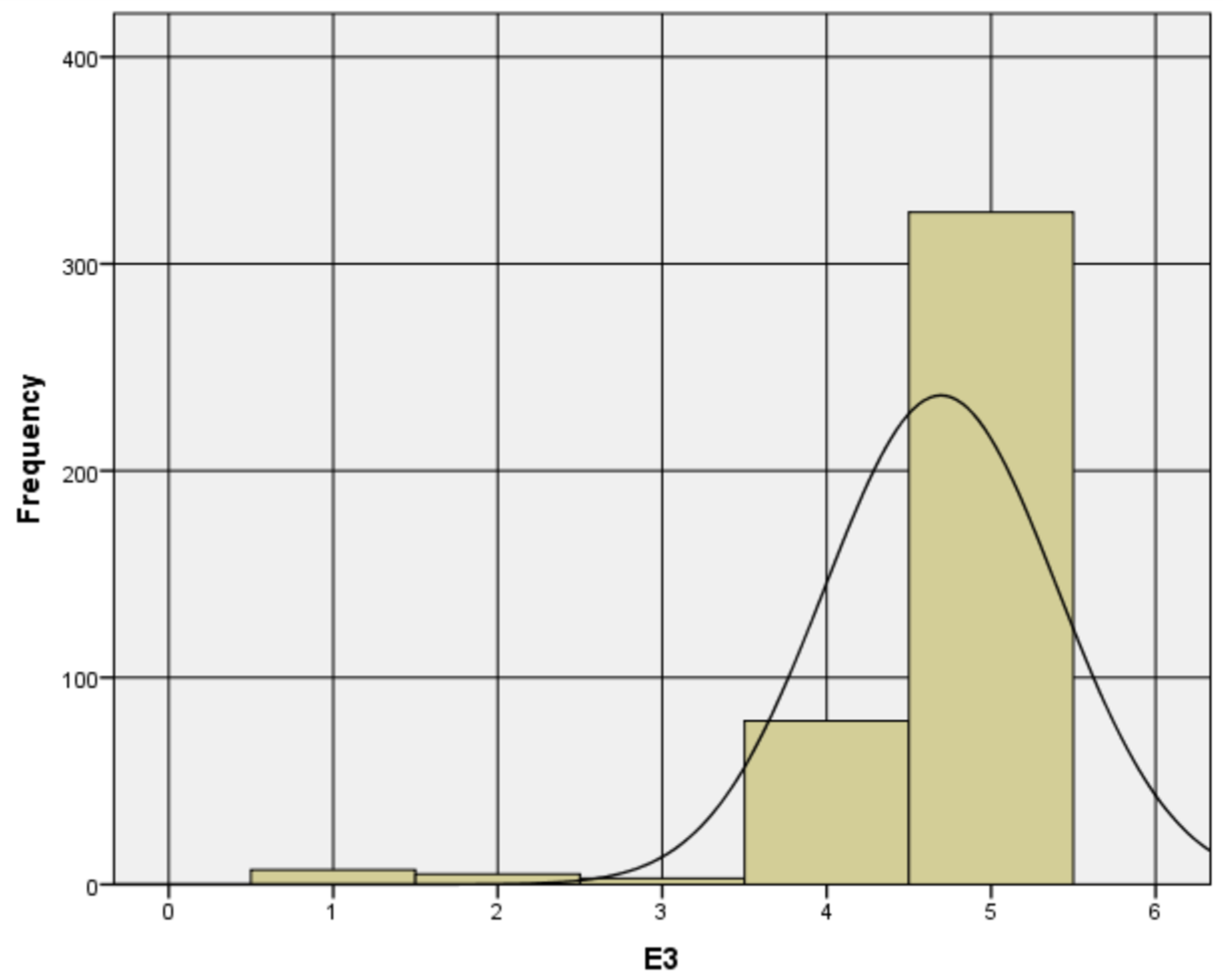

The univariate descriptive analysis revealed substantial variations among the items that compose the dimensions of multidimensional poverty (see

Table 4). Measures of central tendency and dispersion showed differences in the concentration and spread of responses, with means falling within ranges consistent with the ordinal nature of the items. The distributions displayed varying levels of skewness, both positive and negative, indicating response biases toward higher or lower values depending on the item. Similarly, the kurtosis values allowed for the identification of data structures that were roughly concentrated around the mean, suggesting differentiated response patterns across dimensions. These results offer a preliminary empirical characterization of multidimensional poverty conditions prior to conducting inferential comparative analyses between certification categories. Notably, item E3 exhibited kurtosis and skewness values that were considerably atypical, which suggests that a high proportion of households have adults over the age of 16 who are literate (see

Figure 2).

3.2. Phase 2: Mann–Whitney U test

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test showed statistically significant differences in the distribution of a considerable set of multidimensional poverty items when comparing the groups defined by the certification variable (CERT). In particular, significant differences were observed in items HE1, HE3, E1, E2, E3, W1, HO1, HO5, and HO6, suggesting that conditions associated with health, education, work, and home are differentially distributed according to the level of certification. In contrast, items HE2, W2, W3, HO2, HO3, and HO4 did not show statistically significant differences between groups, maintaining comparable distributions

Table 5.

Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U Test by across categories of CERT.

Table 5.

Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U Test by across categories of CERT.

| Variables |

Sig |

Decision |

| HE1 |

0.004 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| HE2 |

0.497 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| HE3 |

0.000 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| E1 |

0.001 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| E2 |

0.000 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| E3 |

0.039 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| W1 |

0.018 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| W2 |

0.075 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| W3 |

0.375 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| HO1 |

0.000 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| HO2 |

0.145 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| HO3 |

0.106 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| HO4 |

0.696 |

Retain the null hyphotesis |

| HO5 |

0.000 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

| HO6 |

0.000 |

Reject the null hypothesis |

These findings reinforce the hypothesis that certification is associated with significant inequalities in specific dimensions of multidimensional poverty, especially those related to health and housing. The use of a non-parametric test supports these results without requiring assumptions of normality, which is consistent with the ordinal nature of the data.

3.3. Phase 3: Chi-Square Test

The application of the chi-square test revealed statistically significant associations between the certification variable (CERT) and several of the multidimensional poverty items. Significant relationships were found for HE1, HE2, E2, W1, W2, HO1, HO2, HO5, and HO6, which are largely consistent with the findings obtained using the Mann–Whitney U test. These associations indicate that the frequencies observed in the response categories of these items vary non-randomly according to the type of certification. On the other hand, items HE3, E1, E3, W3, HO3, and HO4 do not meet the validity requirements of the Chi-Square test (more than 20% of the cells have expected counts less than 5).

Table 6.

Pearson Chi-Square Tests by Certification and Multidimensional Poverty.

Table 6.

Pearson Chi-Square Tests by Certification and Multidimensional Poverty.

| Variables |

N of valid cases |

Expected counts less than 5 (%). |

Test

validity

|

Value |

df |

Asymp. Sig.

(2-sided)

|

| HE1 |

419 |

0.0% |

Yes |

24.323 |

4 |

0.000** |

| HE2 |

419 |

0.0% |

Yes |

21.056 |

4 |

0.000** |

| HE3 |

419 |

40.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| E1 |

419 |

25.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| E2 |

388 |

20.0% |

Yes |

29.965 |

4 |

0.000** |

| E3 |

419 |

60.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| W1 |

419 |

0.0% |

Yes |

10.240 |

4 |

0.037* |

| W2 |

419 |

0.0% |

Yes |

56.512 |

4 |

0.000** |

| W3 |

403 |

25.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| HO1 |

419 |

20.0% |

Yes |

19.562 |

4 |

0.001** |

| HO2 |

419 |

20.0% |

Yes |

11.884 |

4 |

0.018* |

| HO3 |

419 |

40.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| HO4 |

419 |

50.0% |

No |

Not applicable |

| HO5 |

418 |

0.0% |

Yes |

20.446 |

2 |

0.000** |

| HO6 |

419 |

0.0% |

Yes |

28.625 |

4 |

0.000** |

These results reinforce the evidence that certain dimensions of multidimensional poverty particularly those related to health, education, and household conditions are structurally associated with certification status, thereby supporting the hypothesis of structural inequalities between groups.

4. Discussion

The literature indicates that participation in fair trade cooperatives is often associated with higher incomes and improved quality of life, consistent with previous studies conducted in Nicaragua [

76] and Costa Rica [

77]. While the economic benefits are clear, the impacts on education and health are more heterogeneous, with improvements observed in school attendance and certain well-being indicators [

78]. Similarly, participation in organic and fair trade markets contribute to reducing farmers’ vulnerability [

41], although challenges remain in extending these benefits to those facing barriers to meeting certification standards [

32,

79].

The comparative analysis between the results obtained using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Chi-square test reveals a general trend of convergence in the detection of significant differences between certification groups in terms of multidimensional poverty dimensions. However, it is particularly important to highlight those items in which both tests produce divergent results, as this suggests methodological differences sensitive to the type of scale and the way in which the association or difference is operationalized.

Thus, our study, within the education dimension, the results reveal significant differences in years of schooling (E1), school attendance (E2), and literacy (E3), supporting the positive influence of fair trade on educational attainment. This effect is linked to increased coffee income and reduced dropout rates [

78], as well as cooperative investment of premiums in educational projects [

41]. Other studies reinforce this pattern, highlighting the positive impacts of projects funded with premiums [

80] and differences between organic and fair trade standards, with the latter more closely related to educational improvements [

81]. However, the motivation for obtaining certification is not directly associated with the producers’ education level and may be constrained among lower-income farmers [

14,

45]. As [

82] argues, certifications strengthen capacities, but their educational effects require the support of strategic partnerships.

In the health dimension, partial improvements associated with certification were observed, with differences in access to safe drinking water (HE1) and cooking fuel type (HE3), the sanitation item (HE2) did not show significant differences in the Mann-Whitney U test, but it did show a significant association in the Chi-Square test. Previous studies show that prolonged participation in fair trade programs contributes to improved access to medical treatment and generates indirect benefits for community well-being [

78,

83]. Fair Trade’s financial support, particularly in contexts of volatile prices, has enabled community initiatives that enhance health [

79], with positive outcomes in sustainability and public health in certified systems. [

42]

In the employment domain, the findings show improvements only in social security coverage (W1), while child labor (W3) does not exhibit significant differences between certified and non-certified producers, and underemployment (W2) did not show significant differences in the Mann-Whitney U test, but it did show a significant association in the Chi-Square test. This aligns with studies indicating that although Fair Trade increases income and economic stability, its impact on working conditions remains limited [

41,

78]. Research in Nicaragua highlights that Fair Trade standards are not stringent enough regarding temporary labor, which hinders the payment of fair wages [

32]. Despite progress from Premium programs, protecting labor rights continues to be a challenge [

24].

Regarding the housing dimension, significant differences were found in access to electricity (HO1), overcrowding (HO5), and household asset ownership (HO6), indicating improvements in material living conditions among fair trade-linked households. However, no significant changes were observed in roof, and wall materials (HO3 and HO4), and floor (HO2) did not show significant differences in the Mann-Whitney U test, but it did show a significant association in the Chi-Square test. These improvements are linked to increased household wealth and collective investments promoted by cooperatives [

78], aligning with studies that emphasize the role of housing infrastructure in household well-being [

68].

Finally, the comparative analysis between the Mann–Whitney U test and the Chi-square test revealed a general convergence in identifying significant differences between certification groups, although some items such as HE2, W2, and HO2 yielded divergent results across tests. These discrepancies stem from the nature of the methods: while the U test assesses global distributions of ordinal variables, the χ² test detects category-level associations, making it more sensitive to specific differences. Thus, the complementary use of both approaches in social research allows for a more comprehensive understanding of inequalities and specific patterns associated with multidimensional poverty.

5. Conclusions

The results of our research support several dimensions of the alternative hypothesis: fair trade-certified producers experience fewer deprivations in various dimensions of multidimensional poverty compared to their non-certified counterparts, although improvements are not universal. Considering the significance of the Mann-Whitney U test and/or the χ2 test observed significant differences in education (E1–E3), health (HE1–HE3), and partially work (W1 and W2) and housing conditions (HO1, HO5, HO6), indicating that certification and cooperative action are associated with measurable material and social gains. However, indicators such as child labor (W3) and the quality of roofing and wall construction materials (HO3 and HO4) do not show a significant difference or a direct relationship with fair trade certification, which indicates that it is a facilitating factor but not a guarantee of sustainable development.

International evidence supports and nuances these findings: members of fair trade organizations report higher subjective well-being and quality of life, especially with longer cooperative membership [

76], but effects vary across countries and market channels, making generalization risky [

76,

77]. Studies on small-scale producers show that premiums and cooperative networks can reduce vulnerability, improve incomes, and enable investments in education, health, and local infrastructure, though benefits depend on global prices, organizational capacities, and compliance barriers [

32,

41,

79]. Voluntary certifications open pathways toward more sustainable practices but do not, by themselves, ensure systemic change [

84].

From a public policy and sustainability perspective, the linkages between social outcomes in agricultural supply chains and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—particularly SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 3 (health), SDG 4 (education), SDG 8 (decent work), and SDG 11 (sustainable communities)—require integrated indicators that simultaneously capture income, basic services, and household assets. Recent evaluations show that the social impacts of commodity production remain undermeasured compared to environmental impacts and depend on local resources and systemic conditions; operationalizing comparable metrics is key to guiding future interventions [

85].

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Cross-sectional design prevents causal inference, and the use of self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias. Additionally, geographic representativeness is limited to specific coffee-growing regions, so findings are not generalizable to all production areas. Future research could incorporate longitudinal designs, mixed methods, and qualitative indicators to capture community dynamics, perceptions of well-being, and decision-making processes within cooperatives. Furthermore, comparative studies across certifications (organic, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance) and diverse territorial contexts will help better understand which factors enable or constrain the impact of Fair Trade in sustainably reducing multidimensional poverty.

Overall, our findings suggest strengthening cooperative governance, expanding access to infrastructure financing (water, sanitation, housing), and building alliances among producers, certifiers, governments, and NGOs can amplify the positive effects already observed in education, partial health, formal employment, and household assets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-L., and A.V.-M.; methodology, J.M.-L. and G.S.-S.; validation, A.V.-M.; formal analysis, J.M.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.-B., J.M.-L.; writing—review and editing, J.M.-L., N.C.-B., A.V.-M. and G.S.-S.; supervision, A.V.-M.; project administration, J.M.-L. and N.C.-B.; funding acquisition, A.V.-M., N.C.-B. and G.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has received partial funding for the article processing charge (APC), thanks to Basal Funds from the Chilean Ministry of Education, directly or via the publication incentive fund from the following Higher Education Institutions: Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2025), Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Code: APC2025), Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad de Las Américas (Code: APC2025), and Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (Code: APC2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committee of the Doctoral Program in Business Management of POSFACE—UNAH (protocol code N. 100519, on 28 August 2024). All respondents have signed an informed consent form, and the data presented are completely anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Graduate Unit of the Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Administrativas y Contables (POSFACE), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras (UNAH).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ogutu, S. O.; Qaim, M. Commercialization of the small farm sector and multidimensional poverty. World Development 2019, 114, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, M.; Ross, H.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, N.; Pervaiz, U. Measuring multidimensional poverty among farm households in rural Pakistan towards sustainable development goals. Sarhad journal of agriculture 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fu, C.; Li, X.; Ren, F.; Dong, J. What do we know about multidimensional poverty in China: Its dynamics, causes, and implications for sustainability. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2023, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Nguyen-Thi-Lan, H.; Nguyen-Manh, D.; Tran-Duc, H.; To-The, N. Analyzing the status of multidimensional poverty of rural households by using sustainable livelihood framework: policy implications for economic growth. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 16106–16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeje, M. T.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyn, N.; Ayalew, Z.; Nigussie, Z.; Berihun, D.; Adgo, E.; Elias, A. Multidimensional poverty and inequality: Insights from the upper blue Nile basin, Ethiopia. Social Indicators Research 2020, 149, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S.; Lahoti, R. How serious is the neglect of intra-household inequality in multidimensional poverty and inequality analyses? Evidence from India. The Review of Income and Wealth 2021, 67, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. Environmental change and the livelihood resilience of coffee farmers in Jamaica: A case study of the Cedar Valley farming region. Journal of Rural Studies 2021, 81, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamez, M. J.; Legaz, M. C. G. Desarrollo Sostenible 2018. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/.

- Pomati, M.; Nandy, S. Measuring multidimensional poverty according to national definitions: Operationalising target 1.2 of the sustainable development goals. Social Indicators Research 2020, 148, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDGs and MPI|MPPN. Multidimensional Poverty Peer Network; MPPN. Recuperado el 14 de febrero de 2025, de https://www.mppn.org/sdgs-and-mpi/.

- IPM global explora los vínculos entre pobreza multidimensional y conflicto. (2024, octubre 18). MPPN | Red de Pobreza Multidimensional; MPPN. https://www.mppn.org/es/the-global-mpi-explores-links-between-multidimensional-poverty-and-conflict/.

- Beuchelt, T. D.; Zeller, M. Profits and poverty: Certification’s troubled link for Nicaragua’s organic and fairtrade coffee producers. Ecological Economics: The Journal of the International Society for Ecological Economics 2011, 70, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, E. M.; Bruce, E.; Boruff, B.; Duncan, J. M. A.; Horsley, J.; Pauli, N.; McNeill, K.; Neef, A.; Van Ogtrop, F.; Curnow, J.; Haworth, B.; Duce, S.; Imanari, Y. Sustainable development and the water–energy–food nexus: A perspective on livelihoods. Environmental Science & Policy 2015, 54, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyk, F.; Abu Hatab, A. Fairtrade and sustainability: Motivations for Fairtrade certification among smallholder coffee growers in Tanzania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayleur, C.; Balmford, A.; Buchanan, G. M.; Butchart, S. H. M.; Corlet Walker, C.; Ducharme, H.; Green, R. E.; Milder, J. C.; Sanderson, F. J.; Thomas, D. H. L.; Tracewski, L.; Vickery, J.; Phalan, B. Where are commodity crops certified, and what does it mean for conservation and poverty alleviation? Biological Conservation 2018, 217, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.-M.; Sellare, J.; Kouame, C. N.; Qaim, M. Effects of Fairtrade on the livelihoods of poor rural workers. Nature Sustainability 2019, 2, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, A.; Navichoc, D.; Kilian, B.; Dietz, T. Impact pathways of voluntary sustainability standards on smallholder coffee producers in Honduras: Price premiums, farm productivity, production costs, access to credit. World Development Perspectives 2022, 27, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C. M.; Pérez Zelaya, M. E. Fostering sustainability through environmentally friendly coffee production and alternative trade: The case of Café Orgánico de Marcala (COMSA), Honduras. Critique of Anthropology 2023, 43, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Hondureño del Café (IHCAFE). Recuperado el 15 de febrero de 2025, de https://www.ihcafe.hn.

- Krumbiegel, K.; Maertens, M.; Wollni, M. The role of fairtrade certification for wages and job satisfaction of plantation workers. World Development 2018, 102, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A. Asymmetries and opportunities: Power and inequality in Fairtrade wine global production networks. Area 2019, 51, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Duthie, A. C.; Gale, F.; Murphy-Gregory, H. Fair trade and staple foods: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 279, 123586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Fair Trade Organization WFTO Discover the power of fair trade enterprises with. (2023, mayo 11). https://wfto.com/.

- Raynolds, L. T. Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets. Journal of Rural Studies 2012, 28, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Opal, C. Fair trade: Market-driven ethical consumption. SAGE Publications Ltd. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Becker, R. Das Nationale Programm für nachhaltigen Konsum. Ökologisches Wirtschaften – Fachzeitschrift 2017, 32, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossmann, E.; Gomez-Suarez, M. Words-deeds gap for the purchase of fairtrade products: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M. R.; Smith, J. S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J. J. Against the Green: A multi-method examination of the barriers to green consumption. Journal of Retailing 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, S. Moralising markets, marketizing morality. The fair trade movement, product labeling and the emergence of ethical consumerism in Europe. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 2021, 33, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellare, J.; Meemken, E.-M.; Kouamé, C.; Qaim, M. Do sustainability standards benefit smallholder farmers also when accounting for cooperative effects? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2020, 102, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durevall, D. Fairtrade and market efficiency: Fairtrade-labeled coffee in the Swedish coffee market. Economies 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkila, J.; Nygren, A. Impacts of Fair Trade certification on coffee farmers, cooperatives, and laborers in Nicaragua. Agriculture and Human Values 2010, 27, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, L. Auditing the subjects of fair trade: Coffee, development, and surveillance in highland Chiapas. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 2017, 35, 816–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D. L.; Bro, A. S.; Clay, D. C.; Lopez, M. C.; Tuyisenge, E.; Church, R. A.; Bizoza, A. R. Cooperative membership and coffee productivity in Rwanda’s specialty coffee sector. Food Security 2019, 11, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhiani, W. F.; Karyani, T.; Setiawan, I.; Rustidja, E. S. The effect of performance on the sustainability of coffee farmers’ cooperatives in the Industrial Revolution 4.0 in West Java Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojo, D.; Fischer, C.; Degefa, T. (). The determinants and economic impacts of membership in coffee farmer cooperatives: recent evidence from rural Ethiopia. Journal of Rural Studies 2017, 50, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro-Garza, E.; King, D.; Rivera-Aguirre, A.; Wang, S.; Finley-Lezcano, J. A participatory framework for feasibility assessments of climate change resilience strategies for smallholders: lessons from coffee cooperatives in Latin America. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2020, 18, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnu, M.; Offermans, A.; Glasbergen, P. Certification and farmer organisation: Indonesian smallholder perceptions of benefits. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 2018, 54, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, L. Fair trade coffee exchanges and community economies. Environment & Planning 2018, 50, 1027–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, A.; Planas, J. Cooperation, fair trade, and the development of organic coffee growing in Chiapas (1980–2015). Sustainability 2019, 11, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C. Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua? World Development 2005, 33, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, E.; Marton, S. M. R. R.; Baumgart, L.; Curran, M.; Stolze, M.; Schader, C. Evaluating the sustainability performance of typical conventional and certified coffee production systems in Brazil and Ethiopia based on expert judgements. Frontiers in sustainable food systems 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S. The hidden costs of environmental upgrading in global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 2022, 29, 818–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan Jena, P.; Grote, U. Fairtrade certification and livelihood impacts on small-scale coffee producers in a tribal community of India. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 2017, 39, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoyi, K. T.; Mitiku, F.; Maertens, M. Private sustainability standards and child schooling in the African coffee sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 264, 121713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, P. P.; Fischer, C.; De Leo, F. Virtual water flows and economic water productivity of Italian fair-trade: the case of bananas, cocoa and coffee. British Food Journal (Croydon, England) 2022, 124, 4009–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J. G.; Neilson, J. Reviewing the impacts of coffee certification programmes on smallholder livelihoods. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystems Services & Management 2017, 13, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.-M. Do smallholder farmers benefit from sustainability standards? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Food Security 2020, 26, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangile, J. R.; Kadigi, R. M. J.; Mgeni, C. P.; Munishi, B. P.; Kashaigili, J.; Munishi, P. K. T. Dynamics of coffee certifications in producer countries: Re-examining the Tanzanian status, challenges and impacts on livelihoods and environmental conservation. Agriculture 2021, 11, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Loker, W. “we know our worth”: Lessons from a fair trade coffee cooperative in Honduras. Human Organization 2012, 71, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Camayo, F.; Lundy, M.; Borgemeister, C.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Beuchelt, T. Local food system and household responses to external shocks: the case of sustainable coffee farmers and their cooperatives in Western Honduras during COVID-19. Frontiers in sustainable food systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Njeru, E. M.; Garnett, K.; Girkin, N. Assessing the impact of voluntary certification schemes on future sustainable coffee production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles Aguilar, G.; Sumner, A. Who are the world’s poor? A new profile of global multidimensional poverty. World Development 2020, 126, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Deng, X.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, F. Identification and alleviation pathways of multidimensional poverty and relative poverty in counties of China. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2021, 31, 1715–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinko, C. L. J.; Nicholls, R. J.; Daw, T. M.; Hazra, S.; Hutton, C. W.; Hill, C. T.; Clarke, D.; Harfoot, A.; Basu, O.; Das, I.; Giri, S.; Pal, S.; Mondal, P. P. The development of a framework for the integrated assessment of SDG trade-offs in the Sundarban Biosphere Reserve. Water 2021, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Sendhil, R.; Chandel, B. S.; Malhotra, R.; Singh, A.; Jha, S. K.; Sankhala, G. Are Multidimensional Poor more Vulnerable to Climate change? Evidence from Rural Bihar, India. Social Indicators Research 2022, 162, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Menza, M.; Hagos, F.; Haileslassie, A. Impact of climate-smart agriculture adoption on food security and multidimensional poverty of rural farm households in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboor, A.; Khan, A. U.; Hussain, A.; Ali, I.; Mahmood, K. Multidimensional deprivations in Pakistan: Regional variations and temporal shifts. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance: Journal of the Midwest Economics Association 2015, 56, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Shi, L.; Caihong, M.A.; Wang, Y. Spatial heterogeneity of multidimensional poverty at the village level: Loess Plateau. Acta Geographica Sinica 2018, 73, 1850–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarinde, L. O.; Abass, A. B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Adepoju, A. A.; Fanifosi, E. G.; Adio, M. O.; Wasiu, A. Estimating multidimensional poverty among cassava producers in Nigeria: Patterns and socioeconomic determinants. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honduras-MPPN|OPHI, 2016. Org.uk. Recuperado el 26 de julio de 2025, de https://ophi.org.uk/national-mpi-directory/honduras-mpi.

- Padda, I. U. H.; Hameed, A. Estimating multidimensional poverty levels in rural Pakistan: A contribution to sustainable development policies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 197, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. How can energy poverty affect farmers’ health? Evidence from mountainous areas in China. Energy (Oxford, England) 2024, 290, 130074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, A. Assessment of agricultural sustainability in European Union countries: a group-based multivariate trajectory approach. Advances in Statistical Analysis: AStA: A Journal of the German Statistical Society 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Yang, D.; Wu, X.; He, W.; Kong, Y.; Ramsey, T. S.; Degefu, D. M. Development of multidimensional water poverty in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 325, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathenge, M.; Sonneveld, B. G. J. S.; Broerse, J. E. W. Mapping the spatial dimension of food insecurity using GIS-based indicators: A case of Western Kenya. Food Security 2023, 15, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, A. L. The wellbeing of smallholder coffee farmers in the Mount Elgon region: a quantitative analysis of a rural community in Eastern Uganda. Bio-Based and Applied Economics 2020, 8, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntawuruhunga, D.; Ngowi, E. E.; Mangi, H. O.; Salanga, R. J.; Shikuku, K. M. Climate-smart agroforestry systems and practices: A systematic review of what works, what doesn’t work, and why. Forest Policy and Economics 2023, 150, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladini, F.; Betti, G.; Ferragina, E.; Bouraoui, F.; Cupertino, S.; Canitano, G.; Bastianoni, S. Linking the water-energy-food nexus and sustainable development indicators for the Mediterranean region. Ecological Indicators 2018, 91, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoti, A. I. Trend and determinants of multidimensional poverty in rural Nigeria. Journal of development and agricultural economics 2014, 6, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnbruch, K.; González, P.; Apablaza, M.; Méndez, R.; Arriagada, V. The Quality of Employment (QoE) in nine Latin American countries: A multidimensional perspective. World Development 2020, 127, 104738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E.; Ciravegna, L.; Vezzulli, A.; Kilian, B. Decoupling standards from practice: The impact of in-house certifications on coffee farms’ environmental and social conduct. World Development 2017, 96, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional Supervisor de Cooperativas (CONSUCOOP). https://consucoop.hn/#.

- Fairtrade-CHPP. Recuperado el 19 de febrero de 2025, de hhttps://comerciojusto.hn/category/fairtrade/.

- Geiger-Oneto, S.; Arnould, E. J. Alternative trade organization and subjective quality of life: The case of Latin American coffee producers. Journal of Macromarketing 2011, 31, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah, S. Coffee, Farming Families, and Fair Trade in Costa. Latin America Research Review 2008, 43, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E. J.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. Does fair trade deliver on its core value proposition? Effects on income, educational attainment, and health in three countries. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 2009, 28, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, R. Dynamics of Social Capital among Fair Trade and Non-Fair Trade Coffee Farmers. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2018, 28, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sellare, J. New insights on the use of the Fairtrade social premium and its implications for child education. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 94, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.-M.; Spielman, D. J.; Qaim, M. Trading off nutrition and education? A panel data analysis of the dissimilar welfare effects of Organic and Fairtrade standards. Food Policy 2017, 71, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V. E.; Bacon, C. M.; Olson, M.; Petchers, S.; Herrador, D.; Carranza, C.; Trujillo, L.; Guadarrama-Zugasti, C.; Cordón, A.; Mendoza, A. Effects of Fair Trade and organic certifications on small-scale coffee farmer households in Central America and Mexico. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2010, 25, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. "Market Disintermediation and Producer Value Capture: The Case of Fair Trade Coffee in Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala", Rosa, J.A. and Viswanathan, M. (Ed.) Product and Market Development for Subsistence Marketplaces. Advances in International Management, Vol. 20 2007, pp. 319-340. [CrossRef]

- Glasbergen, P. Smallholders do not Eat Certificates. Ecological Economics: The Journal of the International Society for Ecological Economics 2018, 147, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, M.; Dreoni, I.; Ayompe, L. M.; Egoh, B. N.; Ekayana, D. P.; Favareto, A.; Mumbunan, S.; Nakagawa, L.; Ngouhouo-poufoun, J.; Sassen, M.; Uehara, T. K.; Matthews, Z. Mapping social impacts of agricultural commodity trade onto the sustainable development goals. Sustainable Development 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).