1. Introduction

It is well known that the series expansion in powers of h of a properly differentiable composite function

is in the form (Taylor’s theorem):

if

and

are real-valued “nice” functions. How to evaluate the

-th derivative of

, i.e.,

(in Leibniz notation) or

(in Lagrange’s notation)? The immediate answer to this question is the recursive application of the well-known chain rule for the first derivative of composite functions:

together with Leibniz rule for the first derivative of the product of two functions:

which can be generalized as follows for the product of

differentiable functions

:

and for the

-th derivative of the product of

functions:

where:

are the multinomial coefficients, which appear in the multinomial theorem, i.e., the expression of the

-th power of a sum of

terms,

. The sum in (5) is performed over all

-tuples

of nonnegative integers such that

[

1].

As a simple example, let

,

, and

. Applying (2) and (3) recursively to obtain higher-order derivatives of

, after some tedious calculations we obtain for the third derivative of

:

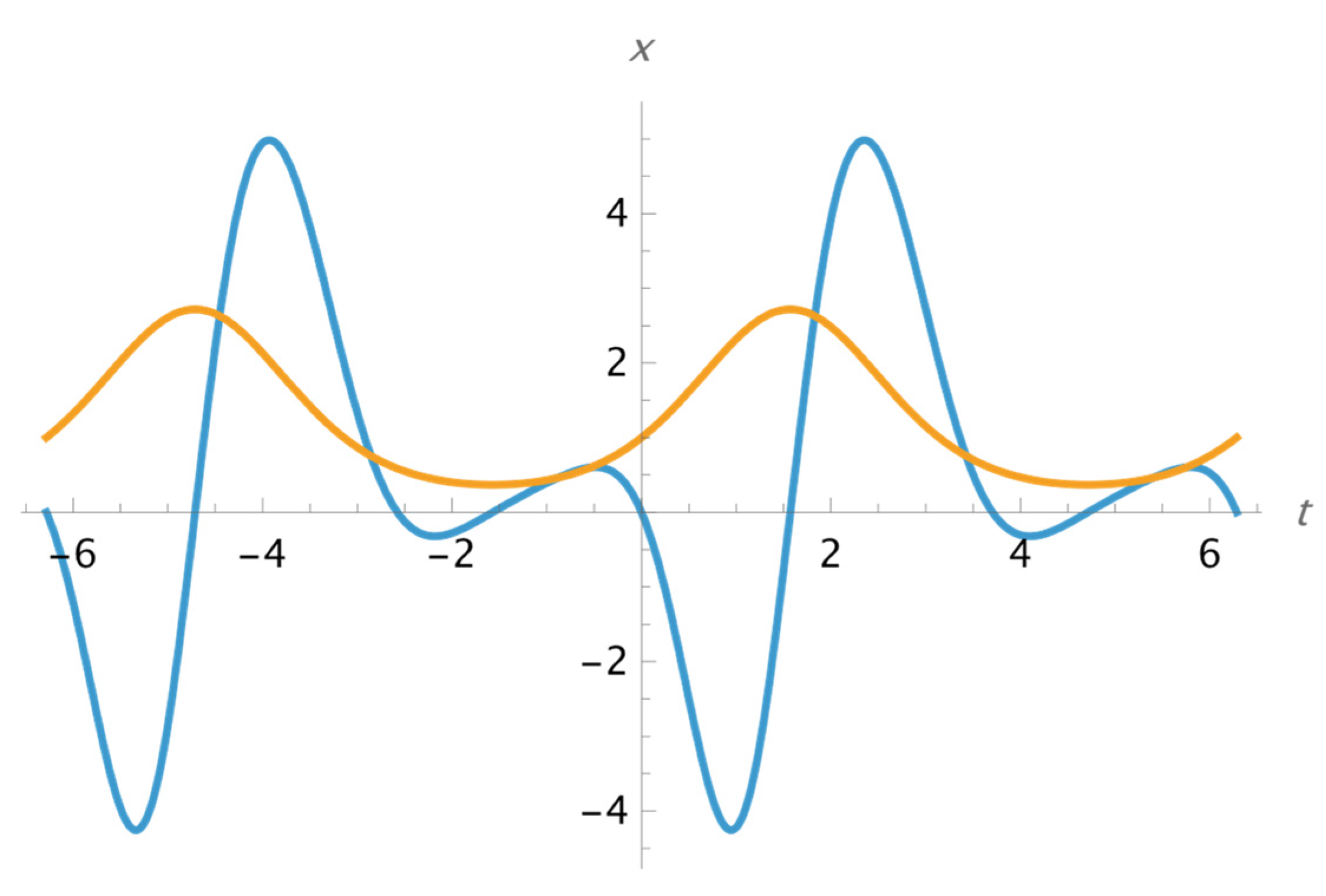

shown in

Figure 1 together with

. Even in this simple case, recursive application of (2) and (3) could lead to cumbersome calculations. For bigger orders of derivation (say, from 5-th order derivatives), the large number of terms to be computed makes the calculation by hand a tedious task.

The generalization of (2) for is the less known - but equally elegant - Faà di Bruno’s formula, published in 1855 and 1857, without any proof or references to previous results, in two alternative forms. The formula is useful for quicker evaluation of m-th derivatives of composite functions without requiring the preliminary evaluation of lesser-order derivatives and with no restrictions on the form of and . Faà di Bruno’s formula has applications in many mathematical and engineering fields, including signal processing issues and mathematical statistics.

This paper revisits the famous formula and its main implications and applications, and outlines a historical portrayal of Faà di Bruno, to make the reader appreciate his versatility and interests, from science to philanthropy. The structure of the paper is as follows. This introduction with the statement of the problem is followed by

Section 2 depicting a short biography of Faà. In

Section 3 his formula is analyzed in three different forms (factorial, combinatorial and determinantal), reworking the simple example of the Introduction to show the calculations to be performed.

Section 4 reviews the most important applications in several scientific fields. Conclusions and references close the work.

2. Historical Notes

The “Cavaliere” Francesco da Paola Virgilio Secondo Maria Faà di Bruno was one of the most original and multifaceted characters of the 19th-century Italian “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), synthesizing an extraordinary experience of science, social engagement and religion: a leading, internationally renowned mathematician, professor at the University of Turin (Italy), Captain of the Royal Army of the Kingdom of Savoy, engineer, inventor, architect, musician and distinguished representative of the social Catholicism [

2,

3].

Born in Alessandria (Italy) on March 29, 1825, Francesco Faà di Bruno (

Figure 2) was the youngest of twelve children -four sons and eight daughters, two of which became nuns - of the marquis Luigi Faà di Bruno and Lady Carolina Sappa de’ Milanesi. He was raised in a home characterized by love of the arts and special attention to the poor, coming from the strong Catholic faith of his family.

He joined the “Regia Accademia Militare di Torino” (Royal Military Academy) in 1840 and participated in the first Italian independence war in 1848. From 1849 to 1851 and from 1854 to 1856 Faà di Bruno was in Paris to improve his mathematical knowledge, attending courses at the Sorbonne, the Collège de France and the École Politechnique. Studying with Augustin Louis Cauchy, Urbain Jean-Joseph Le Verrier (the discoverer of the planet Neptune) Charles Duhamel, Charles F. Sturm, Michael Chasles, and starting a lifelong friendship with Charles Hermite (another Catholic mathematician, three years older than him), in 1856 Faà di Bruno obtained the title of

Docteur ès Sciences Mathèmatiques (Figure 3).

He discussed two theses (on the Theory of Elimination in mathematics and on the series expansion of the perturbing function in astronomy) with a positive scientific evaluation by Cauchy himself, who became Faà’s model for his ability to combine rigorous mathematical research and a philosophical and religious theory of knowledge [

4], influencing Faà’s conception of the relationship between science and faith (“We do not see the centrifugal force, yet we believe in it”). Together with Cauchy, the French abbot François-Napoléon-Marie Moigno (Abbé Moigno) (

Figure 4) was a great inspiration for Faà’s religious and enthusiastic conception of science, making him understand the importance of scientific divulgation, a task to which Faà dedicated many years of his academic life publicly organizing scientific experiments and writing essays on physics, meteorology and chemistry for interested readers, male and female, regardless of their social status [

5].

The Parisian experience marked a fundamental stage in Faà di Bruno’s life: it was in Paris that the orientations of his future scientific and religious - charitable and social - activity were outlined. The stimulating scientific environment and the first-rate mathematicians with whom he worked lead him not only to deal with cutting-edge problems studied by the international scientific community, but also to have a broad view of the organization of knowledge, teaching and science popularization. Moreover, his relationship with the French catholic world and a European cultural background created a personal vision of the catholic church, involved on religious scenarios as well as education and social issues.

After returning to Italy in 1856, Faà gave mathematics lectures at the University of Turin and at the Military Academy, and in 1876 he was appointed professor. Among his most famous students were Corrado Segre and the mathematician Giuseppe Peano. In the same year (at age 51, with a special support given by Pope Pius IX) he became a catholic priest, carrying out a lot of social and philanthropic activities, especially to improve the hard living conditions of female workers in Turin. In 1859 he had founded in the San Donato area of Turin the “Opera di Santa Zita”, a shelter for unoccupied female workers, using his own money and funds collected in churches, and in 1881 the “Congregation of the Minim Sisters of Our Lady of the Suffrage”, helping to establish refuges for the elderly and the poor. His scientific and social program, pursued with tireless energy, pioneer’s spirit and religious fervor, can be summarized in a sentence that might as well be assumed as his life’s motto:

“Peeling potatoes for the love of God is just as beautiful as building cathedrals of science, faith and art” [

2] (p. 280).

Faà di Bruno died in Turin on March 27, 1888, aged 62, a few months after Giovanni Bosco, one of the founders of the Society of St. Francis of Sales and a close friend of him. In the early 20th century, the cause for his canonization started with the declaration of “Servant of God” by the Archdiocese of Turin. In 1971 Pope Paul VI declared him “Venerable”, and on September 25, 1988, he was beatified by Pope John-Paul II on the centennial of his death (

Figure 5). Since 1998, Faà di Bruno is the patron of the Italian Army’s Engineers Corps (“Corpo degli Ingegneri dell’Esercito”).

Faà di Bruno’s contributions to his generation were ascetical writings, several sacred melodies (known and appreciated by Franz Liszt), the project and construction of the bell tower of the Turinese church “Our Lady of the Suffrage”, the invention of some scientific devices (a differential barometer, an electric alarm clock (in Italian, “svegliarino elettrico”), a writing table for the blind), and about 40 original articles, mostly on elliptic functions and elimination theory, published in journals like the “Journal de Mathématiques” (edited by Joseph Liouville), the famous Crelle’s Journal (Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, “Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics”) (

https://www.degruyterbrill.com/journal/key/crll/html), the “American Journal of Mathematics” of the Johns Hopkins University, and others. He also published three books on elimination theory and on the theory and applications of elliptic functions: “Théorie Générale de l’elimination”, containing an inductive proof of his formula [

6], “Calcolo degli errori” (Turin, 1867), translated into French in 1869 (“Traité élémentaire du calcul des erreurs”), and “Théorie des forms binaries” [

7], also translated into German (Leipzig, 1881), his most influential mathematical work, which contained (20 years later!) a formal proof of his eponymously named formula, presented on page 4 of the book. More “modern” proofs of Faà’s result can be found in [8-14].

3. Faà di Bruno’s Formula: Factorial, Combinatorial and Determinantal Forms

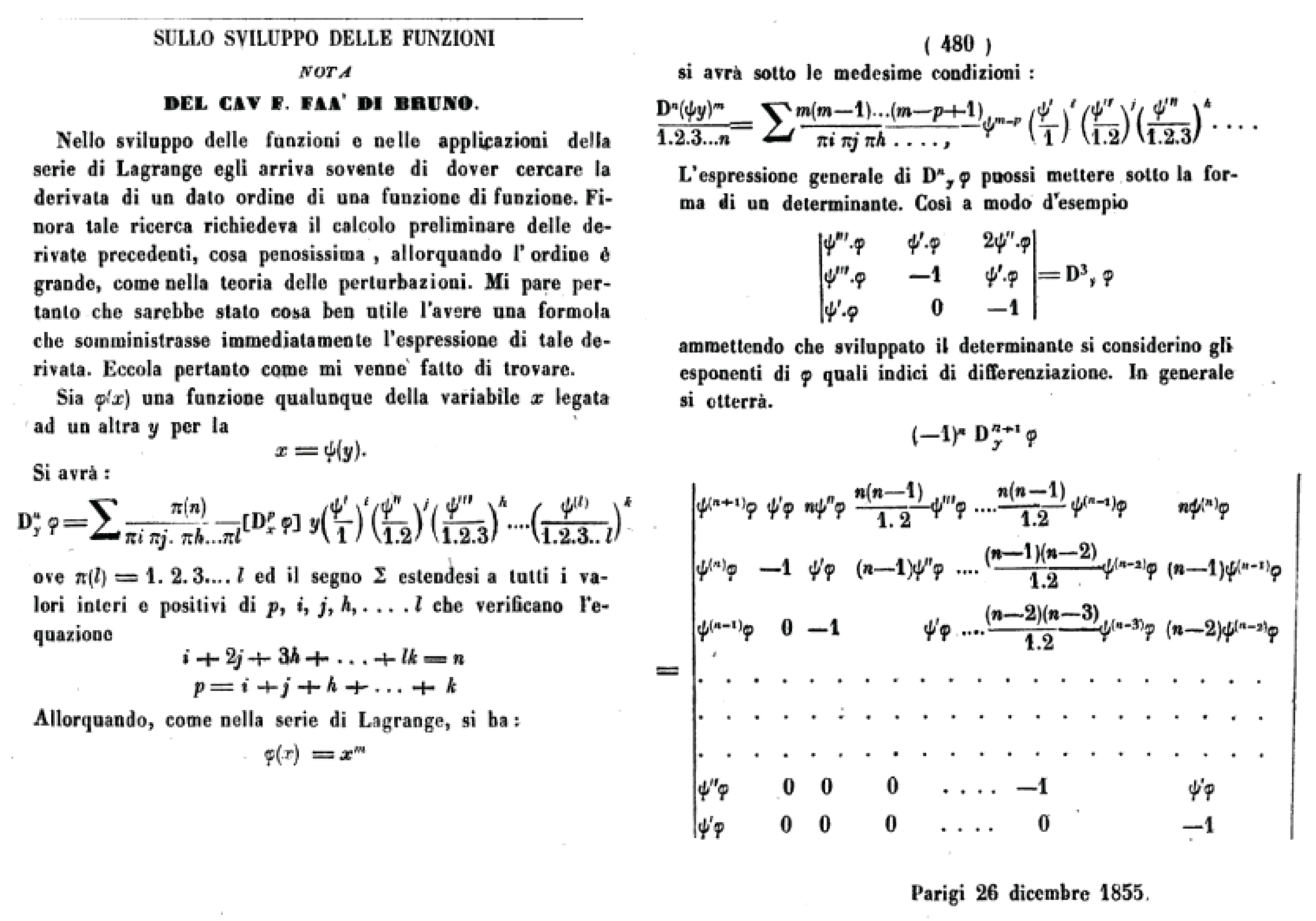

Published in 1855 in a two-page work in the “Annali di Scienze Matematiche e Fisiche” (“Annals of Mathematical and Physical Sciences”,

Figure 6) [

15] and two years later in “The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics” [

16]), Faà di Bruno’s formula generalizes the many formulas known at his age for the

-th derivative of particular composite functions, simplifying the demonstration of some results previously obtained by Edward Waring (1736-1798) and Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827).

The formula states that, if

and

are real-valued functions of one variable, with

and

and

with a sufficient number of derivatives, then the

-th derivative of

, in modern notation, is given by:

where the sum is performed over all the nonnegative integer solutions

of the equation

, and

, the order of the derivative of

, is equal to

. The formula can be proved either by induction or in an elegant alternative form found by Frenkel et al. [

17].

Equation (8) is the so-called “factorial form” of Faà di Bruno’s formula, which is also known in a combinatorial form involving Bell polynomials [

18,

19] and Bell numbers (see later in this paper), developed in the middle of the 20th century by J. Riordan [

20,

21] (Riordan 1946, Riordan 1958), and R. Frucht and G.-C. Rota [

22,

23]:

where the sum is made over the set

of all the partitions

of the set

,

is the cardinality (i.e., the number of blocks) of the partition

, the index

runs through the list of the blocks of the partition

, and

is the cardinality (size) of the block. Despite its elegance, the combinatorial form (9) of Faà’s formula leads to redundant calculations of the terms of

, whereas the form (8) reduces this redundancy.

In the combinatorial form (9), the monomial terms can be collected to give an alternate form:

where the second sum is performed over all the choices of positive integers

which satisfy the constraint:

As thoroughly discussed in [

24,

25], Faà di Bruno’s formula was anticipated (in 1800, 55 years before) by Louis François Antoine Arbogast, a professor of Mathematics in Strasbourg, in his “Traité Du Calcul des Dèrivations” [

26], and successively by A. Lacroix in 1810 and 1819, T. Knight in 1811, H. F. Scherk in 1823, John West in 1838, R. Hoppe in 1845, A. De Morgan in 1846, and J.F.C. Tiburce Abadie (an artillery captain also known as “T.A.”) in 1850. However, Faà developed an elegant and original version of (8), involving a determinant, never published before:

where

,

denotes

and the exponents of

, obtained in the development of the determinant, are to be considered as differentiation indices (e.g.,

means

. This beautiful matrix formulation, also reported in [

27], should be considered the “real” Faà di Bruno’s formula.

It is also worth noting that in 1996 Constantine and Savits presented a multivariate Faà di Bruno’s formula, for computing arbitrary partial derivatives of composite functions [

28]. In [

29] the basic bivariate case, with two functions of two variables, i.e.,

and

is developed, generalizing the result for

functions of

variables. An interesting study of different interpretations of Faà di Bruno’s formula can be found in [

30], where connections are explored with the Lagrange’s inversion formula, Hopf algebras (recently used in quantum field theory [

31], Lie algebras, combinatorial Hopf algebras, and the formula is interpreted in operadic terms (An operad -lexical blend of “operations” and “monad” - is an algebraic structure consisting of abstract operations having a given number of arguments, or inputs, and one output, together with rules on the composition of these operations [

32]).

3.1. A Numerical Example: Third Derivative of a Composite Function

Let . To evaluate the third derivative according to the factorial form (8), we look at the solutions of the equation , with nonnegative integers and (recall that is the order of the derivative of the external function ).

We have three possible solutions:

;

.

In the first case,

and we obtain:

In the second case,

and we get:

In the third case,

and the corresponding term is:

Assembling the terms (13), (14) and (15), the final result is:

With the same reasoning, it can be shown that for

we have:

For a generic value of

, every term of

has the following form:

with

positive integers (obviously,

).

Looking at the combinatorial form (9) of the formula, we also note that the number of terms is equal to , that is, the number of ways of writing the integer as a sum of positive integers, without considering the order, which is the same as the number of partitions of the set .

The total number of partitions of an

-element set is the Bell number

(after the 1934 paper by the mathematician and divulgator Eric Temple Bell [

33]), defined recursively as [

34]:

with

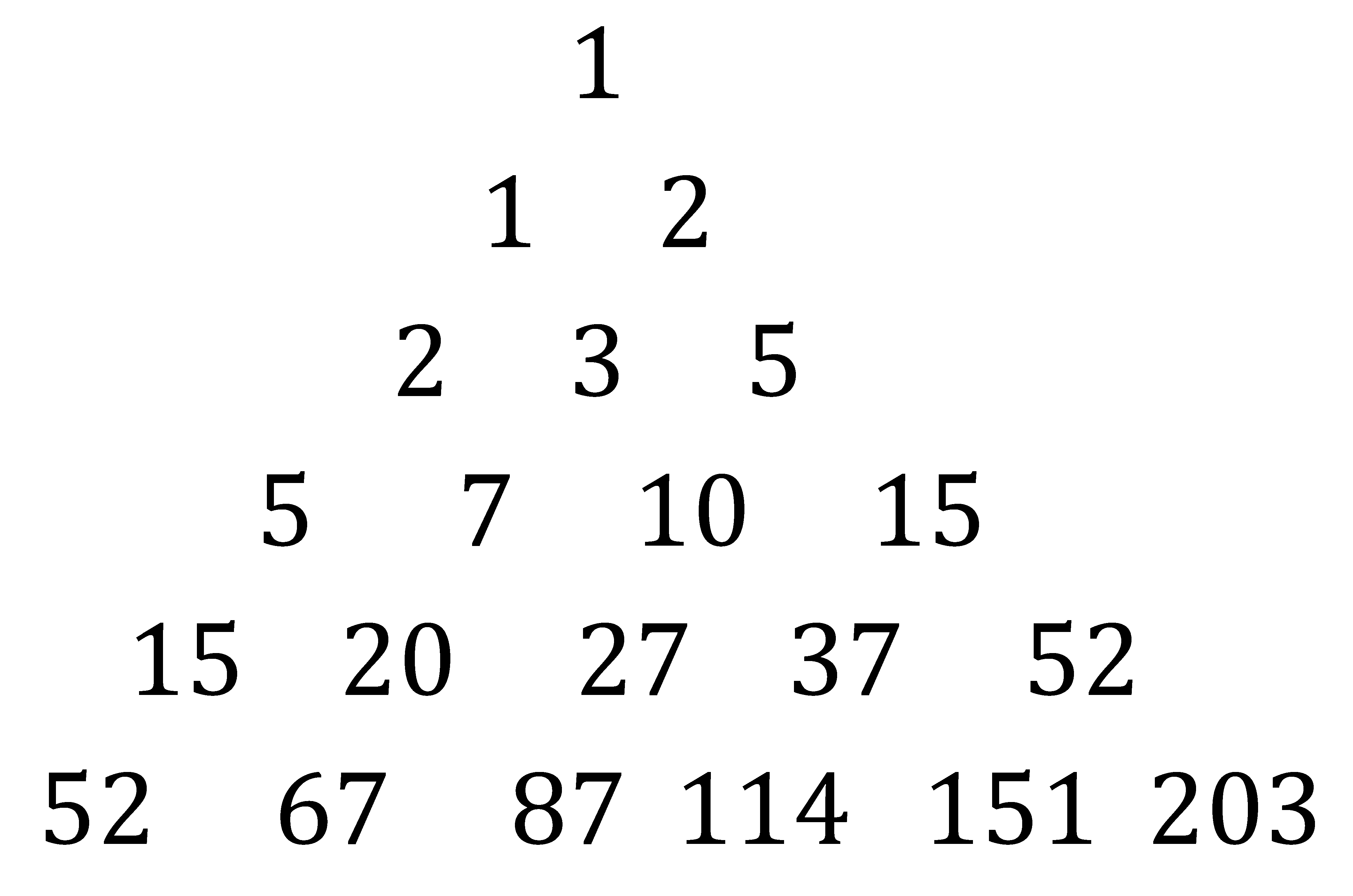

. The first six Bell numbers are

These numbers can be computed using the Bell triangle, constructing by copying the first value of each row from the last value of the preceding row, and, for the successive values of the row, adding the number to the left and to the above left. This rule is similar to the construction rule of Tartaglia’s triangle, since each row of the Bell triangle can be viewed as a weighted sum of binomial coefficients [

35].

The triangle can be computed using the following

Mathematica (the well-known symbolic computation package, now simply named Wolfram) instruction, which uses the built-in functions

BellB[n] for the Bell numbers and

Binomial[n,m] for the binomial coefficients. As an example, the first six rows of the Bell triangle (also called Peirce triangle or Aitken’s array, from the two scientists that discovered independently the sequence in 1880 and 1933 respectively [

36]) are given by the following instruction:

where

are on the left side,

on the right side.

For large

, we recall that the asymptotic expression of

is the wonderful Hardy-Ramanujan formula [

37]:

In

Table 1 the terms of

for

1 to 5 are shown (Mortini [

38] calculates the explicit form of Faà di Bruno’s formula for

up to 10). It is worth noting that the sums of the coefficients of the terms for

are equal to the Bell numbers

respectively.

We can verify the correctness of the result (16) using iteratively the chain rule (2). Using (16) to evaluate the third derivative of our simple example of Sec. 1 , we obtain (7) in a more effective way.

4. Applications of Faà di Bruno’s Formula in Engineering Mathematics

Pure mathematics. Faà di Bruno’s formula has been applied in the integrability theory for nonlinear partial differential equations [

39], in the inversion of multivariate power series [

28,

40], in modular form theory and differential operators [

41], and in the study of inverse relations related to power series [

42].

Combinatorics. The formula has been used to obtain some recurrence formulas for the exponential complete Bell polynomials [

43], combinatorial identities involving Stirling numbers of the first and second kind,

and

, Lah numbers

(also known as Stirling numbers of the third kind), which are the number of partitions of the set

into k nonempty tuples, harmonic numbers [

44], and combinatorial determinant evaluation [

45]. It also helps solving problems involving partitions and arrangements, such as counting labeled structures in graph theory. Very recently, several partition-theoretic generating functions, e.g., the theta quotients from Ramanujan’s lost notebook, MacMahon’s partition functions, and reciprocal sums of parts in partitions, have been revisited through Faà di Bruno’s approach, providing a unified interpretation and a useful framework for deriving new identities [

46].

Mathematical statistics. The formula is used to calculate the

-th order moments and cumulants of a distribution function

and the so-called

-statistics, i.e., symmetric polynomial functions of the observations [

47]. In [

28] the multivariate version of Faà’s formula is used to calculate mixed moments of compound nonhomogeneous and filtered nonhomogeneous Poisson processes. Hoppe [

48] shows that Faà di Bruno’s formula allows one to derive the distribution functions from a finite population for sampling with replacement (multinomial) or sampling without replacement (multivariate hypergeometric). In physics, examples of these distributions are Fermi-Dirac, Bose-Einstein and Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions. Moreover, Faà’s formula has a deep relationship with some sampling formulas in population genetics (due to Ewens and Pitman) developed in the 1990s. Applications of the formula to multivariate normal distributions and distribution of a normalized sum of iid (independent, identically distributed) random variables can be found in [

49].

Physics and Engineering. Faà di Bruno’s formula finds application in solving complex differential equations and modeling physical systems. In nonlinear dynamics, for example, higher-order derivatives of composite functions often appear in perturbation methods or stability analysis [

50].

Aerospace, telecommunications and signal processing. In the study of waveforms and signals, the formula helps compute derivatives of composite functions representing modulated signals. Stochastic point processes and spatial clustering models can benefit from Faà di Bruno’s formula for variational calculus [

51]. Also, higher derivatives of composite functions are involved in approaches for deriving algorithms for multiple target tracking from radar systems [

52], with practical applications using sequential Monte Carlo methods [

53] and Gaussian mixture PHD (Probability Hypothesis Density) filters [

54].

Machine Learning and Optimization. In modern applications like machine learning, Faà di Bruno’s formula is used in backpropagation algorithms for neural networks and fractional gradient computation [

55], as well as for theoretical exploration of the structures inherent to the bio-inspired spiking neural networks (SNN), recently exploited for neuromorphic computing and sparse computation [

56]. The formula also underpins techniques for computing higher-order derivatives, which are essential in optimization problems and training deep learning models.

5. Conclusions

This paper explored the different forms of the famous Faà di Bruno’s formula (12), a brilliant generalization of the chain rule, involving the expression of the -th derivative of a composite function, and elegantly blending calculus with combinatorics, since the formula involves summing over partition of integers. We presented the classic 1855 statement of Faà’s formula, together with more modern forms involving Bell numbers and Bell polynomials, putting in evidence the deep combinatorial structure of the formula and the connections with discrete mathematics and probability theory. The usefulness of Faà’s formula has been demonstrated with a simple example outlining the calculations to be made. A quick review of the principal applications in pure mathematics and several engineering mathematics fields, from control theory, aerospace, telecommunications and signal processing to symbolic calculus, automatic differentiation tools in computer systems, machine learning and optimization, is also presented. In addition, we provided a historical account of the formula and of Faà di Bruno’s original and multifaceted personality, capable of harmonizing positivistic instances, religious faith and social engagement and conceiving science as a fundamental vehicle of freedom and concord towards the realization of union among peoples.

Equation (12) and its different forms, extended to multivariate functions, are a cornerstone of higher-order calculus and, though intimidating at a first glance, they show beautiful symmetry and logic. Faà di Bruno’s formula ability to elegantly handle the complexity of composite functions and their higher-order derivatives makes it an indispensable tool for researchers and practitioners alike. By bridging the gap between abstract theory and real-world problems, this formula continues to demonstrate the timeless relevance of Faà di Bruno’s mathematical ingenuity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and S.P.; investigation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, A.F. and S.P.; supervision, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stanley, R.P. , Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume I, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2012, Vol. I, p. 21.

- Giacardi, L. (Editor), Francesco Faà di Bruno – Ricerca scientifica, insegnamento e divulgazione (“Scientific research, teaching and popularization”). Studi e Fonti per la Storia dell’Università di Torino, XII Deputazione Subalpina di Storia Patria – Torino, Palazzo Carignano, 2004 (in Italian), pp. 671.

- O’Connor, J.J. , Robertson, E.F., Francesco da Paola Virgilio Secondo Maria Faà di Bruno. 2012. Available online: https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Faa_di_Bruno/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Cauchy, A. , Sur la recherche de la vérité. Bulletin de l’Institut Catholique 1842, 14, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Faà di Bruno, F. , Sunti di Fisica, Meteorologia e Chimica con tavole ad uso delle scuole maschili e femminili. G. B. Paravia e Comp., Firenze, Torino, Milano, 1870 (in Italian).

- Faà di Bruno, F. , Théorie Générale de L’Ėlimination. Librairie Centrale des Sciences Leiber et Faraguet, Paris, France, 1859, p. 3. Available online: https://www.google.it/books/edition/Théorie_générale_de_l_éimination/PfYGAAAAcAAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1&dq=theorie+generale+de+l%27elimination+faa+di+bruno&pg=PP7&printsec=frontcover (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Faà di Bruno, F. , Théorie des Formes Binaires. Librairie Brero, Turin, Italy, 1876. Available online: https://archive.org/details/thoriedesformes01brungoog/mode/2up (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Jordan, C. , Calculus of Finite Differences, 2nd Edition. Chelsea Publishing Company, New York, N.Y., 1950, pp. 33-34.

- Roman, S. , The Formula of Faà Di Bruno. The American Mathematical Monthly 1980, 87, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, R.A. and Johnson, C., Topics in Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 421-424.

- Flanders, H. , From Ford to Faà. The American Mathematical Monthly 2001, 108, 559–561. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, S. , Deriving Faà di Bruno’s formula for the derivative of a composite function via composition of integers. 2014. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.0519 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Abel, U. , A new Faà di Bruno type formula. Elemente der Mathematik 2015, 79, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivaraya, K. , Faà di Bruno’s Formula for Generalizing the Chain Rule to Higher Derivatives – An Analysis. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews (IJRAR) 2020, 7, 903–910. [Google Scholar]

- Faà di Bruno, F. , Sullo sviluppo delle funzioni. Annali di Scienze Matematiche e Fisiche 1855, 6, 479–480. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=ddE3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA479&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 30 July 2025). (in Italian).

- Faà di Bruno, F. , Note sur une nouvelle formule de calcul différentiel. The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 1857, 1, 359–360. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=7BELAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA359&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Frenkel, I.B. , Lepowsky, J. and Meurman, A. (Editors), Vertex Operator Algebras and the Monster. Pure and Applied Mathematics Vol. 134. Academic Press, New York, 1988, Chap. 8, Proposition 8.3.4.

- Bell, E.T. , Exponential Polynomials. Annals of Mathematics 1934, 35, 258–277. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1968431 (accessed on 30 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Comtet, L. , Advanced Combinatorics – The Art of Finite and Infinite Expansions. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, Holland, 1974, Sec. 3.4, pp. 137-140.

- Riordan, J.; , Derivatives of composite functions. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 52, No. 8, 1946, p. 664. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/derivatives-of-composite-functions-3jwn31d39f.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Riordan, J. , An Introduction to Combinatorial Analysis. Wiley, New York, 1958, pp. 35-37.

- Frucht, R. A combinatorial approach to the Bell polynomials and their generalizations. In Tutte, W.T. (Editor), Recent Progress in Combinatorics, Proceedings of the 3rd Waterloo Conference on Combinatorics. Academic Press, New York, 1969, pp. 69-74.

- Frucht, R. and Rota, G.-C., Polinomios de Bell y particiones de conjuntos finitos. Scientia 1965, 126, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Craik, A.D. , Prehistory of Faà di Bruno’s Formula. The American Mathematical Monthly 2015, 112, 119–130. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30037410 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Johnson, W.P. , The Curious History of Faà di Bruno’s Formula. The American Mathematical Monthly 2002, 109, 217–234. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2695352 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Arbogast, L.F.A. , Du Calcul des Dérivations. Imprimerie de Levrault, Fréres, Strasbourg, France, 1800. Available online: https://archive.org/details/ducalculdesdri00arbouoft/page/viii/mode/2up (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Knuth, D.E. , The Art of Computer Programming – Volume 1 – Fundamental Algorithms, 3rd Edition. Addyson Wesley Longman, 1997, p. 483.

- Constantine, G.M. , Savits, T.H., A Multivariate Faà di Bruno Formula with Applications. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1996, 348, 503–520. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155187 (accessed on 30 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Leipnik, R.B. and Pearce, C.E.M., The multivariate Faà di Bruno formula and multivariate Taylor expansion with explicit integral remainder theorem. The ANZIAM (Australian & New Zealand Industrial and Applied Mathematics) Journal 2007, 48, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Frabetti, A. and Manchon, D., Five interpretations of Faà di Bruno’s formula. In Kurush, E.F., Fauvet, F. (Editors.), Faà di Bruno Hopf Algebras, Dyson-Schwinger Equations, and Lie-Butcher Series. IRMA Lectures in Mathematical and Theoretical Physics 21. European Mathematical Society, 2015, pp. 91-147.

- Kreimer, D. , Yeats, K., Diffeomorphisms of Quantum Fields. Mathematical Physics, Analysis and Geometry 2017, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, M. , Shnider, S., Stasheff, J., Operads in Algebra, Topology and Physics. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, Volume 96. American Mathematical Society, 2002, pp. 349.

- Bell, E.T. , Exponential Numbers. The American Mathematical Monthly 1934, 41, 411–419. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2300300 (accessed on 30 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wilf, H.S. , generatingfunctionology. Academic Press, 1994.

- Farina, A. , Giompapa, S., Graziano, A., Liburdi, A., Ravanelli, M., Zirilli, F., Tartaglia-Pascal’s triangle: a historical perspective with applications. Signal, Image and Video Processing (SIViP) 2013, 7, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, N.J.A. (Editor), Sequence A011971- Aitken’s array: triangle of numbers {a(n,k), n >= 0, 0 <= k <= n} read by rows, defined by a(0,0)=1, a(n,0) = a(n-1,n-1), a(n,k) = a(n,k-1) + a(n-1,k-1). The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, 1964. Available online: https://oeis.org/A011971 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hardy, G.H. and Ramanujan, S., Asymptotic formulæ in combinatory analysis. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Vol. 2, Issue 17, pp. 75–115. In Collected papers of Srinivasa Ramanujan, AMS Chelsea Publ., Providence, RI, 1918, pp. 276–309.

- Mortini, R. , The Faà di Bruno formula revisited. Elemente der Mathematik 2013, 68, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabat, A. , Efendiev, M.K., On applications of Faà di Bruno’s formula. Ufa Mathematical Journal 2017, 9, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.G.G. and Prochno, J., Faà di Bruno’s formula and inversion of power series. 2022.

- Meguedmi, D. , Sebbar, A., Faà di Bruno’s Formula and Modular Forms. Complex Analysis and Operator Theory 2016, 10, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-S. , Hsu, L.C., Shiue, P.J.-S., Application of Faà di Bruno’s formula in characterization of inverse relations. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2006, 190, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A. , Chen, Z., A unified approach to some recurrence sequences via Faà di Bruno’s formula. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 2011, 62, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzer, H. , Kouba, O., Applications of the Formula of Faà di Bruno: Combinatorial Identities and Monotonic Functions. Results in Mathematics 2021, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenchang, C. , The Faà di Bruno formula and determinant identities. Linear and Multilinear Algebra 2006, 54, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsusaka, T. , Applications of Faà di Bruno’s formula to partition traces. Research in Number Theory 2025, 11, 69. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40993-025-00651-9 (accessed on 30 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, E. Applications of Faà di Bruno’s Formula in Mathematical Statistics. The American Mathematical Monthly 1955, 62, 340–348. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2307040 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hoppe, F.M. , Faà di Bruno’s formula and the distributions of random partitions in population genetics and physics. Theoretical Population Biology 2008, 73, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savits, T.H. , Some statistical applications of Faà di Bruno. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 2006, 97, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Liberzon, D., Higher Order Derivatives of Lyapunov Functions for Stability of Systems with Inputs. IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Nice, France, 2019, pp. 6146-6151. [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.E.; and Houssineau, J. Faà di Bruno’s formula for chain differentials. 2013. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1310.2833v1 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Clark, D.E. , Houssineau, J., Faà di Bruno’s formula and spatial cluster modeling. Spatial Statistics 2013, 6, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, B.-N. , Singh, S., Doucet, A., Sequential Monte Carlo Methods for Multi-Target Filtering with Random Finite Sets. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2005, 41, 1224–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, B.-T. , Vo, B.-N. and Cantoni, A., Analytic Implementations of the Cardinalized Probability Hypothesis Density Filter. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2007, 55, 3553–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canan, C. , Çubukçu, M., Implementation of Caputo type fractional derivative chain rule on back propagation algorithm. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q. , Cheng, J.-Y., Wu, J.-H., Zhang, G., Xiong, H., Gu, B., Zhou, Z.-H., On the Intrinsic Structures of Spiking Neural Networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).