1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal problems are a common occupational risk for dentists worldwide, affecting their muscles, tendons, joints and ligaments due to the physical demands of their work. Awkward positions, whether sitting or standing near patients, can strain the spine and limbs. Postures like bending the neck, raising arms, twisting, and repetitive hand movements put stress on the musculoskeletal and peripheral nervous systems, especially in the neck and upper limbs. Dentists often experience neck pain, shoulder aches, back issues, and upper limb discomfort. Procedures like extractions can further strain the elbow and wrist, sometimes causing chronic tendon sheath inflammation and cumulative trauma disorders over time. The longer or more frequent static strains occur, the greater the risk of injury due to overuse of muscles, joints and other tissues [

1,

2].

Tendons are essential components of the musculoskeletal system, helping transfer loads throughout the body and enabling movement. With around 4,000 tendons and ligaments in the human body, they provide crucial stability and support. These dense connective tissues link muscles to bones, absorbing and distributing forces. Made primarily of collagen fibers and tendon-resident cells, tendons are arranged in a parallel structure within an extracellular matrix (ECM) rich in proteoglycans. This hierarchical organization creates strong, fibrous tissues. Collagen gives tendons their tensile strength, while proteoglycans add viscoelastic properties. The ECM features structural proteins like collagen and elastin, specialized proteins such as fibrillin and fibronectin, and proteoglycans. Once thought to be simple and passive, tendons are now understood as complex structures vital to both health and disease [

3].

Healthy tendons usually heal and restore their balance after an injury, but this process can be more challenging for groups like older adults, postmenopausal individuals, people with obesity, or those with diabetes. These factors increase the risk of tendon injuries and conditions like tendinopathy. Tendinopathy occurs when the tendon’s normal healing process is disrupted, often linked to overuse and resulting in overlapping pathological issues. The term "tendinopathy" refers to various non-rupture tendon problems, including acute, chronic, and degenerative conditions, usually involving persistent pain, swelling, reduced performance, and other difficult symptoms. It’s common in physically demanding jobs and can lead to significant pain and disability. Tendinopathy is marked by changes in the microstructure, composition, and cellular makeup of the tendon [

4,

5].

Tendons, often called "mechanical bridges," are tough, fibrous tissues that link muscles to bones. They transfer muscle forces to bones for joint movement and act like springs, storing and releasing energy. Tendons also help absorb external forces to shield muscles from overload while temporarily storing energy. With a nerve supply and sufficient blood flow, tendons are highly adaptable and tolerant of stress. Their proprioceptive role is vital for maintaining posture and balance. Tendon movement depends on a sensory system that uses elastic mechanisms to store and release energy. Tendon cells detect mechanical signals through deformations in their membrane or cytoskeleton; this tension reaches the nucleus via a mechanosensory system, triggering metabolic responses in mechano-transduction. This process helps maintain tissue balance by adapting to mechanical loads. The cytoskeleton adjusts when the extracellular matrix experiences strain [

6,

7].

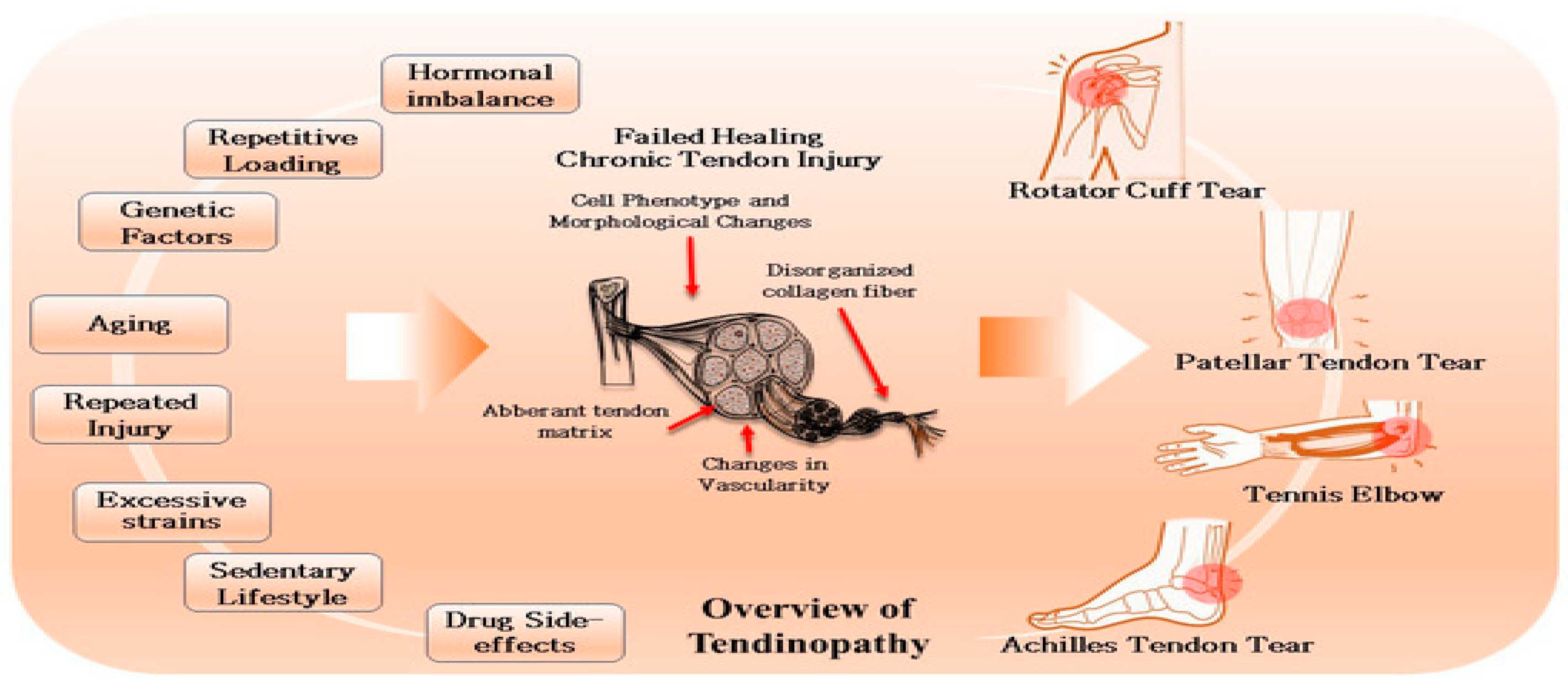

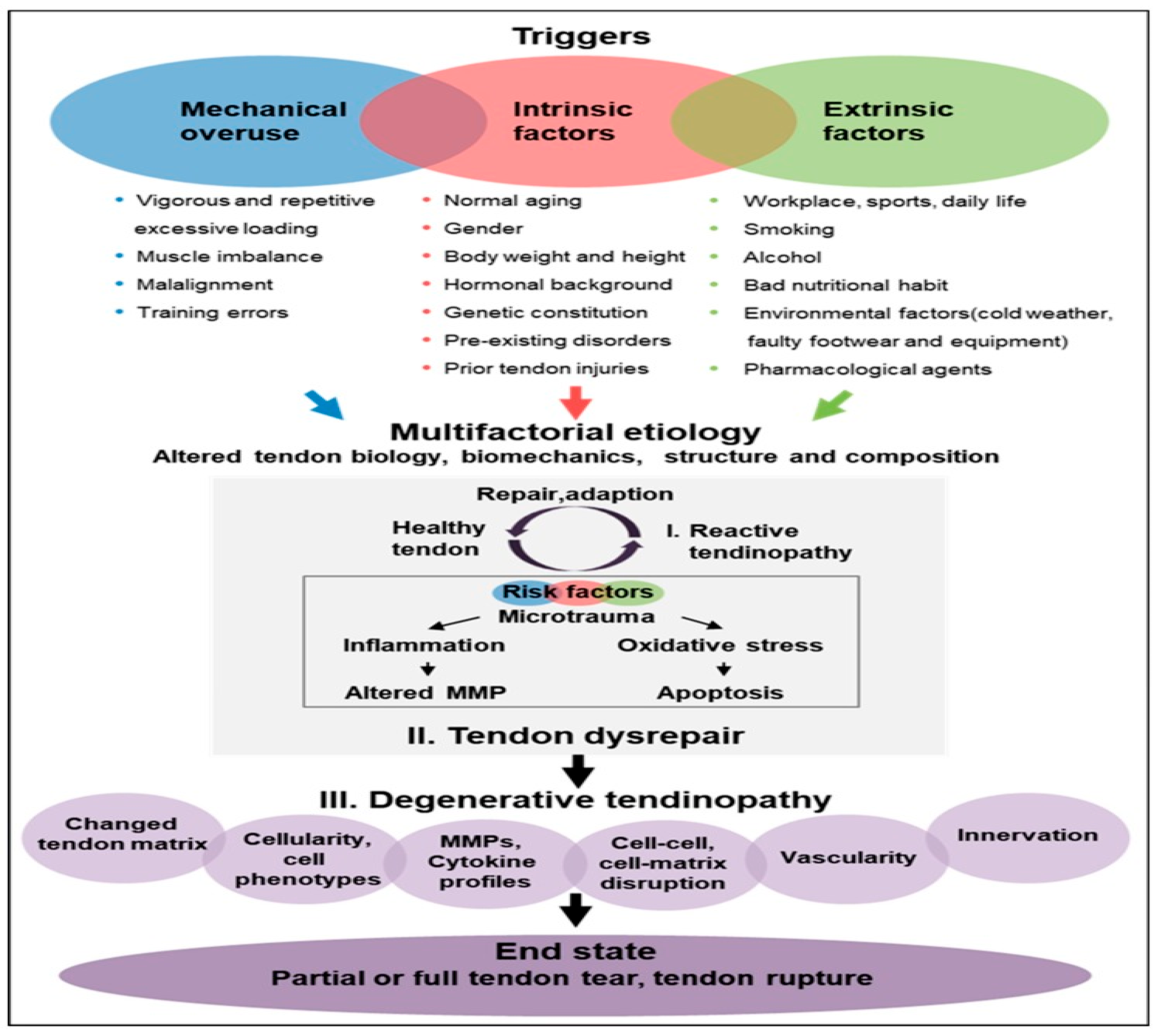

Tendinopathy leads to ongoing pain, reduced performance, swelling, and other symptoms. This condition is associated with compressive loading caused by acute trauma, repetitive stress, or overuse, which interferes with cell communication and causes tissue damage or rupture. Contributing factors include mechanical risks, intrinsic elements like age, gender, and genetics (such as connective tissue disorders), and pre-existing conditions, along with extrinsic factors like lifestyle, poor nutrition, smoking, alcohol, and stress. Environmental factors such as cold weather, footwear, and certain medications also play a role. Repetitive microtrauma from overload or overuse can lead to collagen fibril rupture and activation of the innate immune system. These triggers lead to cellular responses, and inflammation, although the exact mechanisms are still unclear. External cells might encourage vascular and nerve growth, inflammation, and pain, while abnormal tendon stem cell activity can result in fat accumulation and calcification [

8].

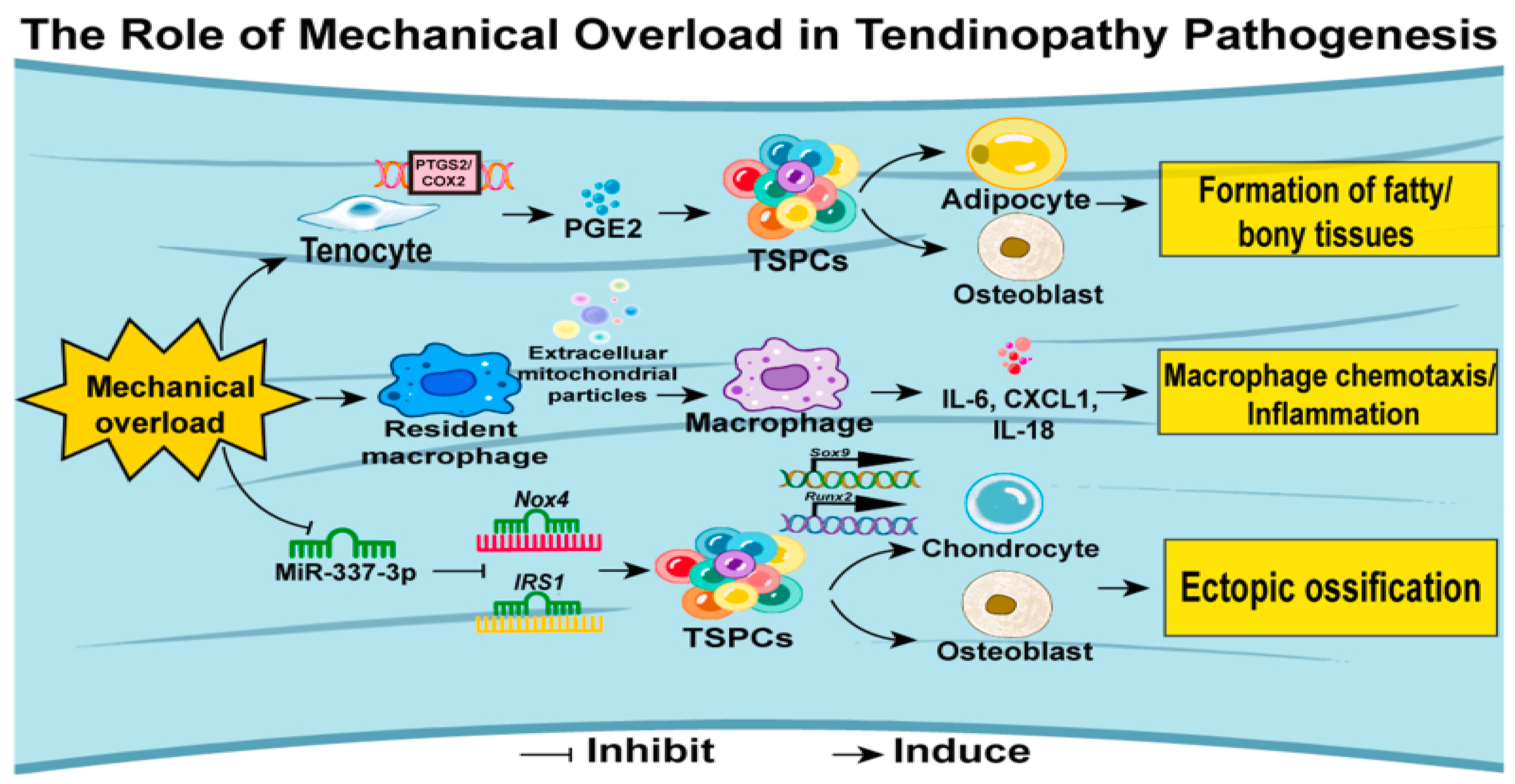

Tendon degeneration is thought to result from three main factors: mechanical overuse, vascularization, and aging. Human tendons adapt to loading by increasing collagen synthesis and metalloproteinase activity, enhancing mechanical strength, viscoelastic properties, and stress resistance, which allows higher load tolerance. However, repetitive activities can subject tendons to significant forces, risking overuse injuries. Repeated tensile loading below the injury threshold may cause microdamage, increasing the risk of tendinopathy or rupture. Microdamage can lead to vascular in-growth, including necrotic capillaries, which compromise vascular function and create local tissue hypoxia, increasing the chances of degeneration. Aging further weakens tendon mechanical properties and metabolism, making them more prone to damage and degeneration. Tendon degeneration often involves fibrin buildup, calcifications, and lipid deposits, resulting from a failure in matrix adaptation and remodeling due to an imbalance between matrix breakdown and synthesis under various conditions [

9].

The causes of tendinopathy are varied, likely interconnected, and still largely unproven. Suggested mechanisms include disrupted apoptosis, mechanical strain, an imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs), genetic factors, nerve growth, and inflammation. Tendinopathy usually develops gradually, causing pain associated with activity, reduced function, and sometimes localized swelling. Clinical exams often reveal pain when the affected area is stretched or pressed. Imaging methods like ultrasound and MRI are particularly useful for confirming the diagnosis. [

10].

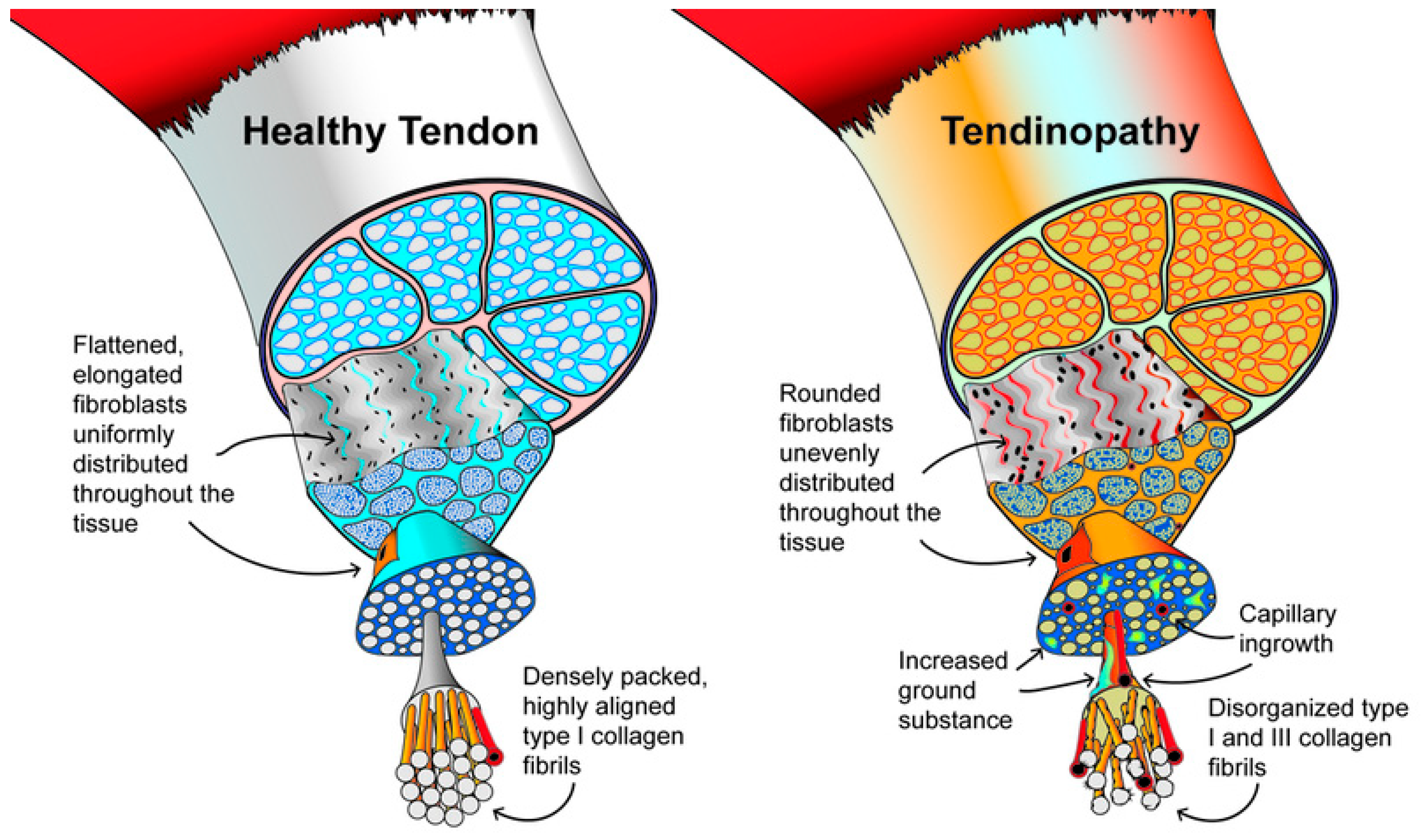

Tendons get their incredible tensile strength from the organized linear alignment of collagen fibrils, which are formed by covalent cross-linking of collagen molecules. The primary component is Type I collagen, making up 60–85% of their dry weight, with the rest consisting of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), glycoproteins, and other collagen types like III, XII, and V. Tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPCs) or Tenocytes consider as fibroblast-like cells, form the basic structure of tendons, neatly positioned between collagen fibrils. They regulate the extracellular matrix (ECM) and respond to external stimuli, helping tendons adapt to mechanical loads [

11].

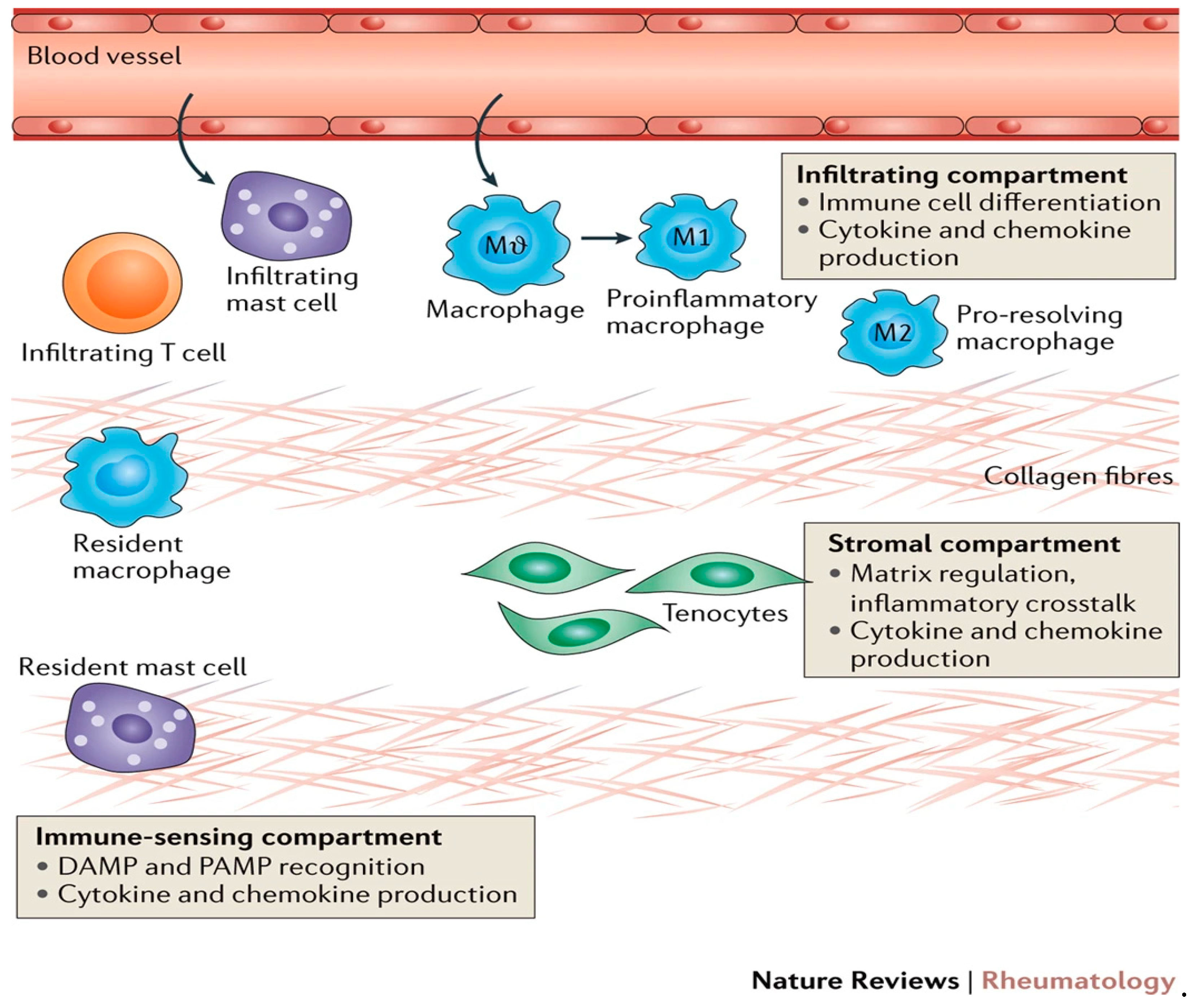

Tendons contain a small group of resident macrophages that typically remain inactive and self-renew under normal conditions. After a tendon injury, these cells become activated, releasing inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6, playing a key role in the repair process and scar tissue formation. Macrophages differentiate into M1 and M2 types, with M1 producing pro-inflammatory mediators and M2 assisting in resolving inflammation and remodeling tissue. The transition from M1 to M2 is crucial for shifting from inflammation to tissue repair and scar formation. Additionally, macrophage-derived exosomes containing miRNA, especially via the miR-21-5p/Smad7 pathway, contribute to peri-tendinous fibrosis after tendon injury, showcasing their complex role in healing and scar formation [

12].

In tendinopathy, the extracellular matrix (ECM) undergoes changes like collagen disorganization and fibrocartilaginous transformation due to increased ECM proteins. Early tendon damage triggers the production of type III collagen as a quick repair, but its disorganized structure weakens the tendon. Over time, type III collagen is replaced by type I collagen, restoring normal structure. Microscopically, tenocytes become rounder, proliferate more, and show signs of apoptosis. Electron microscopy reveals tendinopathic collagen fibers with angulation, varying diameters, and ECM buckling, reflecting reduced integrity. Affected tendons also show increased neovascularization [

13].

In 2008, Cook JL et al. introduced a model for load-induced tendinopathy with three stages: reactive tendinopathy, tendon disrepair, and degenerative tendinopathy. In the reactive phase, the tendon’s cross-sectional area expands due to cell proliferation and matrix changes, reducing stress. Tendon cells take on a chondroid-like shape, increasing protein production, particularly proteoglycans, which retain water and cause fibrosis. With adequate rest, the tendon can recover, but without healing, tendon disrepair occurs. This stage involves matrix breakdown, tendon thickening, collagen disruption, and increased vascularity and nerve growth. Recovery is still possible with proper load management and exercises. The degenerative stage features severe cellular and matrix damage, including apoptosis, disorganized matrix, fiber loosening, and minimal healing capacity. At this point, the tendon is filled with vessels and mucoid substances, with very limited ability to repair [

14].

After a tendon injury, the affected area commonly shows pain, swelling, redness, and reduced function. Once considered a degenerative condition caused by overuse, recent research highlights the role of inflammation in tendon injuries. The debate around inflammation in tendinopathy has evolved. Initially thought to be the main pathological change, inflammation was associated with pain and dysfunction, leading to the term "tendonitis." Later studies found no inflammatory cells like macrophages at the site, leading to the term "tendinitis" being discarded. Advances in pathology and immunology revealed macrophages, T cells, and B cells in chronic tendinopathy through monoclonal antibodies. Increasing evidence now underscores inflammation's role in tendinopathy development [

15].

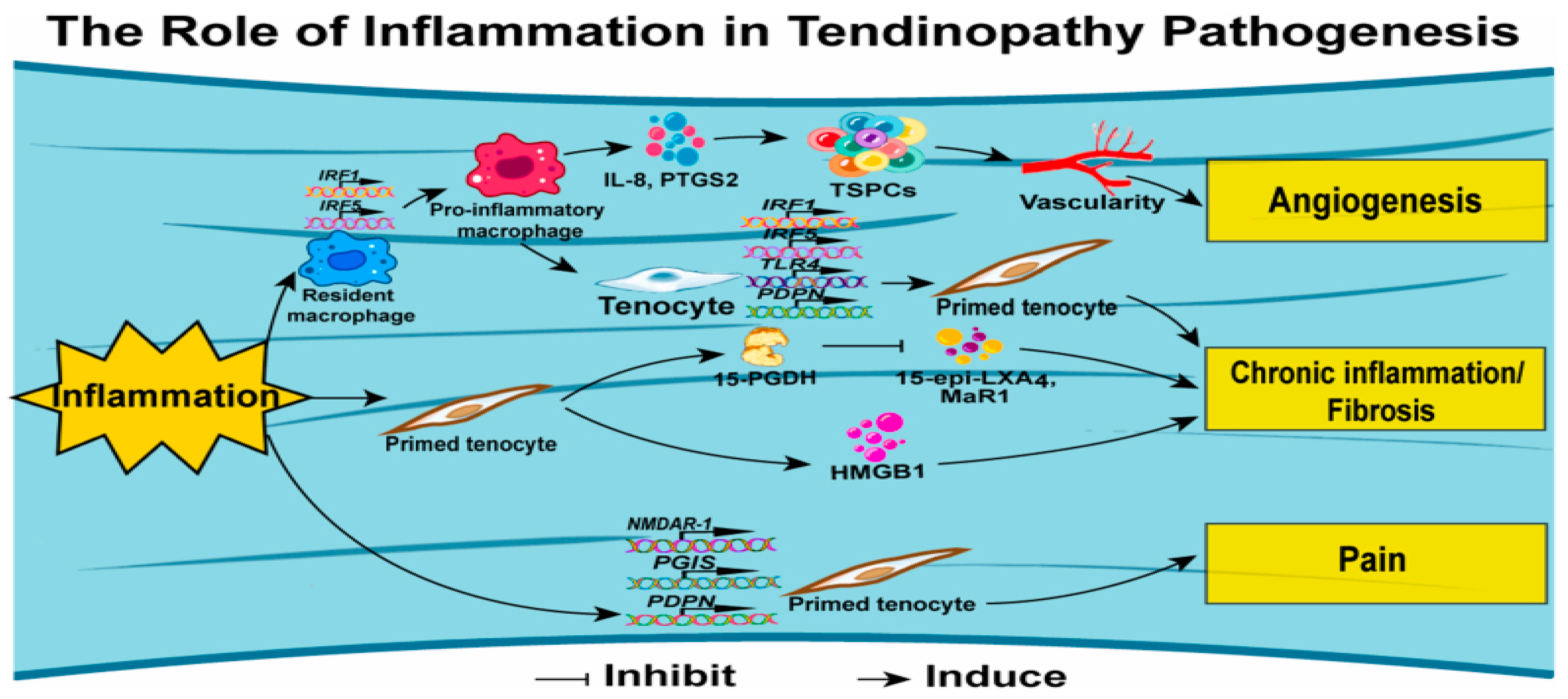

Inflammation plays a vital role in wound healing by clearing dead tissue and waste. The healing process occurs in three stages: inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling. During the inflammatory stage, necrotic cells are removed, and a temporary extracellular matrix forms to support cell renewal. The proliferative phase starts when tissue-resident cells activate and transform into myofibroblasts, aiding tendon repair. Nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB), a key transcription factor, regulates inflammation by promoting mediators like Interleukin-1β, Interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor, and chemokines CCL2 and CXCL10 after tendon injury. These pathways trigger pro-inflammatory gene expression and tissue remodeling to restore balance [

16].

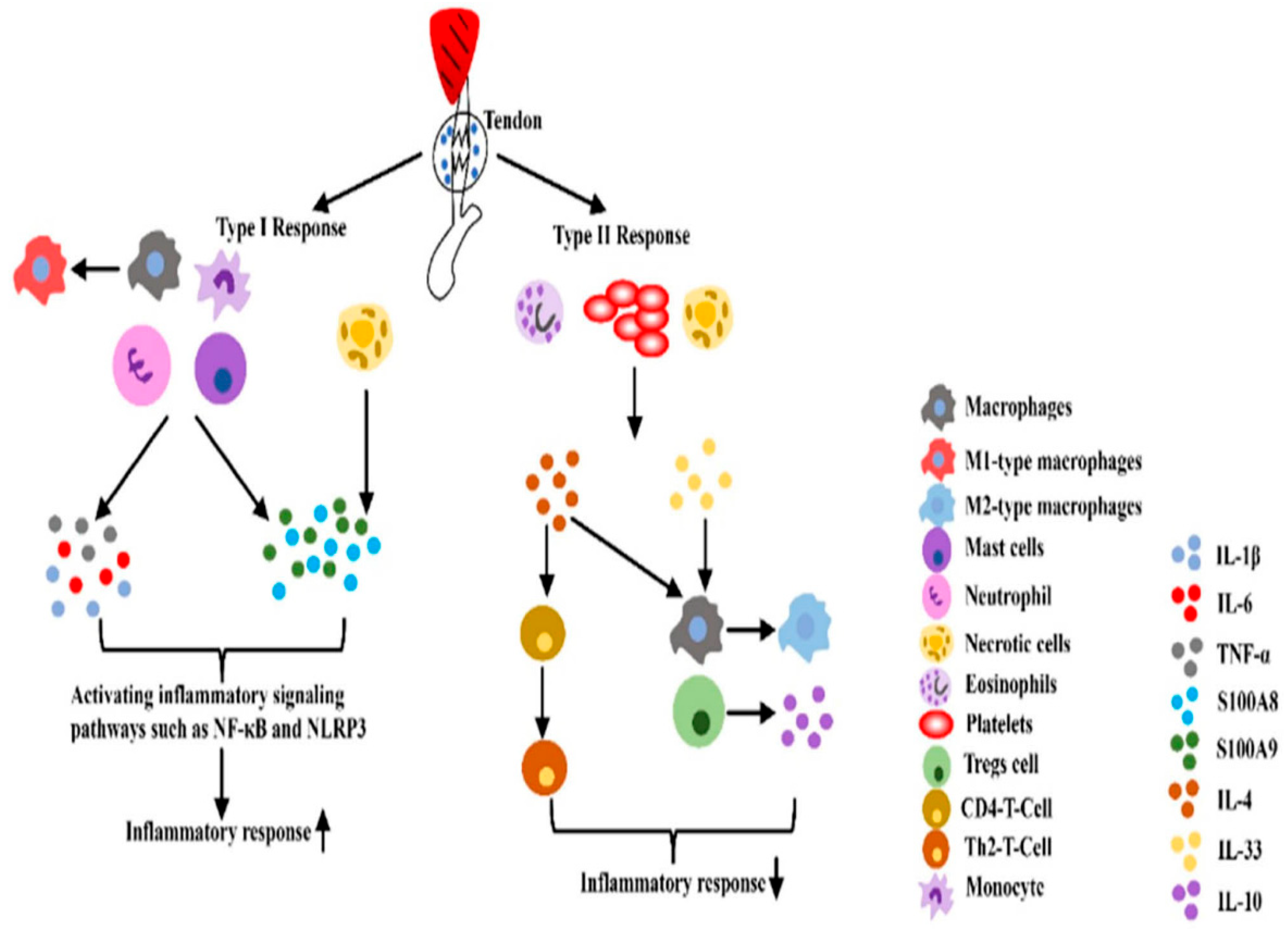

Prolonged inflammation can cause excessive matrix buildup and fibroblast activation, leading to scar tissue formation. To balance the pro-inflammatory type I response, the body triggers a type II immune response, releasing IL-4 or IL-33 from damaged cells. IL-33 activates macrophages, Tregs, and other immune cells, while Tregs produce IL-10, an anti-inflammatory factor that resolves type I inflammation. IL-4 aids this process by promoting M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. IL-1, considered as important regulators of innate and adaptive immunity, and a key cytokine inflammation, contributes to extracellular matrix breakdown, suppression of tendon cell markers, and pain through PGE2-induced vasodilation. After a tendon injury, inflammatory factors like IL-1 and TNF-α are released by neutrophils and macrophages during the exogenous healing phase. IL-1β decreases the expression of early growth response gene 1 (Egr1), Col1, and Col3, while increasing matrix metalloproteinases that promote collagen breakdown, resulting in ongoing tissue degradation [

17].

Inflammatory responses are managed through two-way communication between the brain and the immune system. When tissue is injured, inflammatory mediators are released, directly activating nociceptors. PGE2, produced from arachidonic acid via the COX2 pathway, is released by resident cells in damaged tissue and immune cells, driving inflammation and nociception. During this stage, different signaling pathways work together to balance pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators, maintaining ECM homeostasis. Tendon repair involves endogenous and exogenous healing processes. Endogenous healing depends on tenocytes proliferating, migrating, and producing collagen under cytokine influence. Exogenous healing, led by fibroblasts and inflammatory cells, plays a vital role in tendon recovery. After tendon injuries, inflammatory cells like neutrophils and macrophages release factors such as IL-1β and TNF-α, which activate IκB phosphorylation through various signaling pathways. This leads to its degradation by proteolytic enzymes and activates NF-κB signaling, which regulates the inflammatory response. [

18].

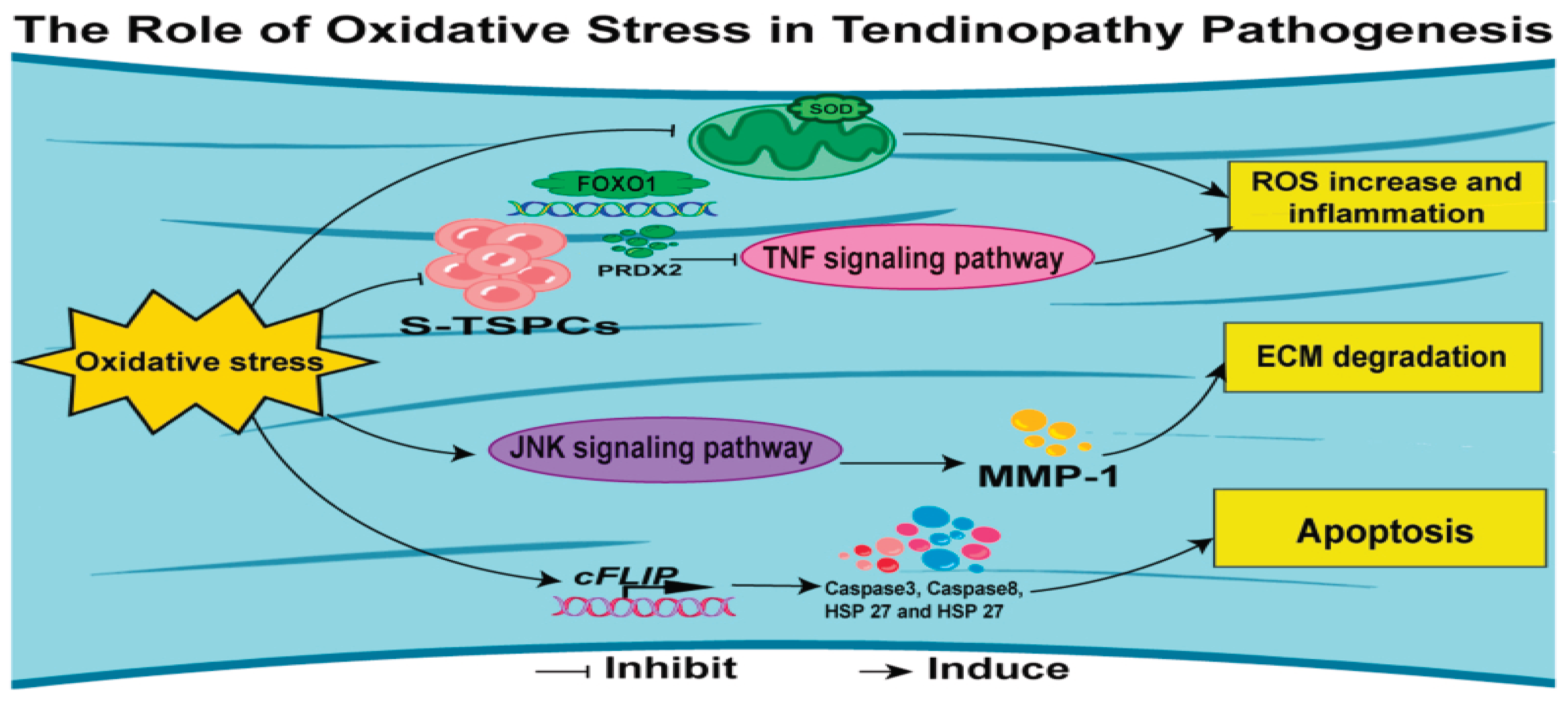

Oxidative stress happens when cells and tissues produce too many reactive oxygen species (ROS), overwhelming the antioxidant system's ability to manage them. Studies show a strong link between oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases, with ROS acting as key signaling molecules. Oxidative stress and inflammation are deeply connected, influencing each other. Inflammatory cells release large amounts of ROS at inflammation sites, causing more oxidative damage, while ROS and their byproducts worsen inflammation and tissue damage. Managing oxidative stress and inflammation, aiding tissue repair, and preventing chronic disease progression are vital strategies. Oxidative stress is also significant in tendinopathy, especially during intense physical activity when the body's defenses against ROS are overwhelmed. Excess ROS can damage cells through oxidative changes, leading to dysfunction and tissue harm. [

12].

Treating tendinopathy typically includes reviewing medical history, performing physical exams, and utilizing advanced imaging to develop effective strategies. Radiographs play a key role in diagnosis, prognosis, and tracking outcomes. MRI is especially useful for chronic cases, while diagnostic ultrasound has gained popularity as a cost-effective option for dynamic tendon assessments. A study comparing ultrasound and MRI with surgical outcomes in 27 patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy found both methods equally effective for prognosis. Although imaging tools aren’t essential for diagnosing tendinopathy, they are valuable for surgical planning. [

19].

Managing tendinopathy is challenging because of its complexity, as treatments don’t always work for everyone, and strong evidence for many therapies is often missing. Traditional approaches focus on reducing pain and inflammation, but studies reveal minimal inflammation in tendons that struggle to heal. Early-stage tendinopathy is usually treated conservatively with activity adjustments, rest, NSAIDs, corticosteroid injections, and cold therapy. Physiotherapy combined with techniques like myofascial therapy, ultrasound, iontophoresis, phonophoresis, and acupuncture can help if there’s no significant structural damage. However, corticosteroids and NSAIDs are debated due to their potential to cause spontaneous tendon ruptures. Other non-surgical options like ultrasound, shock wave therapy, eccentric exercises, and low-intensity laser treatment aim to promote structural repair [

6].

Eccentric Training (EC) is widely regarded as one of the best treatments for tendinopathies, with both eccentric and aerobic exercises helping to improve patient function. EC reliably boosts functionality in those with tendinopathy. Consistent, structured exercise strengthens tendon tissue by encouraging the growth of new collagen fibers. However, exercise can be a double-edged sword; while essential for recovery, overdoing it can be harmful. Too much strain and repeated stretching can cause collagen fibers to slide against each other, break cross-links, and trigger a degenerative process [

20].

Biophysical stimulation is one of the therapeutic methods used to promote healing in tendon and ligament injuries. It includes a range of conservative treatments aimed at supporting recovery, often applied to well-vascularized tissues that are likely to heal without surgery or used alongside surgical procedures. Physical therapy and rehabilitation exercises play a pivotal role in managing tendinopathies. The non-surgical interventions aim to alleviate pain, reduce inflammation, improve blood supply in the affected area, and enhance the overall function of the tendon. The introduction of percutaneous needle electrolysis, applying a galvanic current to activate the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and promote collagen-mediated tendon regeneration, represents an innovative non-surgical approach [

21].

Diet and nutrition are crucial for tendon recovery and prevention, complementing physical treatments. Vitamin C (VC) stands out for its antioxidant benefits and its role in collagen synthesis. Studies reveal that VC supplementation enhances collagen production, aiding tendon repair, while a deficiency in VC can slow healing by reducing pro-collagen production. VC-enriched gelatin has been shown to boost collagen synthesis for up to 72 hours after consumption, underscoring its value for tendon health and metabolism. VC’s impact is even greater when combined with other nutraceuticals. Research indicates that a combination of type 1 collagen peptide, chondroitin sulfate, sodium hyaluronate, and VC significantly improves tendon healing and reduces pain compared to control groups, highlighting the potential of bioactive compounds in tendon therapies. Curcumin, is a natural herbal medication known for its anti-inflammatory effects, also shows promise for tendon injuries [

22].

Regenerative therapies like stem cells and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are showing great potential in treating musculoskeletal issues such as osteoarthritis and tendinopathy. However, their high costs often make them inaccessible for many patients.

Growth factors such as bFGF, GDF5, GDF6 (BMP13), GDF7 (BMP12), IGF1, PDGF, TGF-b1, TGF-b2, VEGF, and their combinations play a key role in tendon and ligament healing and development. To boost the healing process, some studies combine cells and scaffolds with growth factors or PRP. Researchers have also explored approaches like local injections of recombinant proteins, over-expression vectors, and biomaterial carriers for sustained release. While these treatments often show great results in the early stages of healing, their long-term success remains inconsistent and limited [

23].

Biologically active adjuncts are becoming more common in treating tendons injuries, with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) being a popular option. PRP is made from the patient’s blood, spun in a centrifuge to remove red blood cells, leaving a solution rich in platelets and plasma. It contains growth factors like PDGF, VEGF, TGF-β, EGF, FGF, and IGF. Over the last 20 years, research has highlighted PRP’s potential in orthopedics, though high-quality trials proving its effectiveness in ligament and tendon healing are still needed [

24].

Cell therapy is a novel exciting area in tissue engineering, where delivered cells help synthesize matrix materials and support tendon healing. These stem cells are characterized by smaller cell bodies, larger nuclei, multipotency, and self-renewal, with factors like age, growth factors, cytokines, genes, the extracellular matrix (ECM), and media influencing their differentiation. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer advantages over fibroblasts, such as self-renewal, differentiation into various mesenchymal lineages, and secretion of factors that regulate inflammation. Their self-renewal ensures a sufficient cell supply, while their ability to differentiate into tenocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and myoblasts aids in regenerating tendon-to-bone and tendon-to-muscle interfaces. However, recent studies show MSCs primarily support tissue repair by secreting factors that activate local cells or modulate immune responses. The simplest approach involves injecting MSC suspension directly into injury sites, often paired with carriers like collagen or fibrin gel. More advanced methods include tissue engineering, such as seeding MSCs onto scaffolds before implantation or culturing them on scaffolds in vitro to create neo-tendon tissue, providing initial mechanical support for injuries

. [

25].

Nitric oxide therapies have gained popularity in recent years for treating tendinopathies. The most common approach involves using transdermal nitroglycerin, which the body converts into bioactive nitric oxide through its own nitric oxide synthase. At the cellular level, nitric oxide supports tenocyte growth and collagen production, while inhibiting nitric oxide synthase slows tendon healing and decreases the mechanical load required for tendon failure [

26].

Non-surgical treatments for tendinopathy are often ineffective for about a third of patients, leaving them with limited relief and prompting them to reduce activities, quit sports, or consider surgery. Surgical options aim to remove damaged tendon tissue or create controlled trauma to stimulate healing, similar to prolotherapy or PRP. Prolotherapy involves injecting an irritant solution into or around the damaged tendon to trigger inflammation and promote healing of the extracellular matrix often affected by tendinopathy. These solutions may also sclerose small blood vessels and pain-sensitive neurons in the tendon. Surgery is typically a last resort when non-surgical methods fail, with the most common procedure being open debridement of the affected tendon or surrounding tissues, along with necessary repair or augmentation [

27,

28].

Surgical repair is the main approach for complete tendon rupture injuries; However, these procedures often face limitations, with 20-94% of patients experiencing issues like rerupture, elongation, muscle atrophy, impaired function, and poor tendon-bone healing. Studies have also raised doubts about the advantages of surgical repair for tendon ruptures, suggesting it may not be better than nonsurgical treatments in reducing rerupture rates or improving tendon tissue quality [

29].

Epigenetic regulators play a key role in disease development, influencing processes like protein recruitment, DNA methylation, histone deacetylation, DNA replication, transcription, and miRNA activity on target genes. They are crucial in starting, progressing, and controlling inflammation, but their role in tendon pathologies remains unclear. Exploring how epigenetic processes impact tendon-specific inflammatory genes could open the door to new treatments for tendon disorders [

22].

Improving tendon healing outcomes remains a significant challenge. Regenerative medicine and tissue engineering strategies aim to tackle this issue, but the healing process is influenced by numerous factors, making it tough to evaluate all biological and microarchitectural variables for an optimal approach. Traditional molecular methods only partially capture the changes in the healing tendon and its complex extracellular matrix (ECM) caused by regenerative strategies, complicating comparisons. Emerging fields like multiomics offer a way to streamline research and boost the likelihood of successful translation [

30].

Gene delivery is another modality which contributes to tendon healing, it involves introducing external gene sequences into target cells or tissues to alter DNA, either boosting or reducing therapeutic protein production. Viral and nonviral vectors, such as adenoviruses, retro-/lentiviruses, and recombinant adeno-associated viruses, help cells use their own machinery to produce proteins over time, reducing the need for frequent injections or high doses of treatments. However, since nucleic acids degrade rapidly in plasma and lose functionality, effective delivery systems are crucial [

31].

The emerging field of multiomics in regenerative medicine combines various genome-wide disciplines and high-throughput platforms, each marked by a unique -omic suffix. These focus on specific aspects of molecular biology's central dogma, such as genomics, metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Each platform can be further divided into "bulk" (tissue-wide) and "spatial" approaches, which include regional, single-cell, or sub-cellular methods. Nuclear or mitochondrial, the core features of multiomic studies are that they do not require a predefined molecular target and allow individual samples to be fully and multidimensionally analyzed in a single experiment. Multiomics identifies biomolecular profiles connecting genotype to phenotype by studying genetic material, proteins, and metabolites. These platforms are useful for understanding, comparing, and defining phenotypic states (e.g., healthy or diseased) and tracking transitions (e.g., cell programming, development, or treatment response). Each sub-field and platform focus on different aspects of cell and tissue metabolism, which, when integrated, provide a more comprehensive picture than a single 'omic platform and suggest reasons for these phenotypic changes. By validating molecular or metabolic targets identified through multiomic analyses, these techniques offer a clearer picture of the functional state by delivering data at the protein level, encompassing lipids, metabolites, and their possible interactions. This improves understanding of upstream and downstream events could eventually lead to new strategies for enhancing patient outcomes [

32].

The focus is on integrating multi-omics to build detailed cellular maps, creating AI tools to process complex data, and studying biomarkers in diverse patient groups. By combining bulk, single-cell, and spatial approaches, researchers can explore the complex layers of musculoskeletal diseases, addressing both systemic issues and tissue-specific interactions. These breakthroughs offer promising advancements in precision medicine, aiming to restore tissue function and improve outcomes for patients with musculoskeletal disorders [

33].

Figures:

Figure 1.

overview of the multifactorial causes and pathological changes involved in tendinopathy ().

Figure 1.

overview of the multifactorial causes and pathological changes involved in tendinopathy ().

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of tendinopathy pathogenesis (7).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of tendinopathy pathogenesis (7).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the morphological features in healthy tendon and tendinopathy. Modified from Scott et al. (26).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the morphological features in healthy tendon and tendinopathy. Modified from Scott et al. (26).

Figure 4.

Immunobiology of tendinopathy (14).

Figure 4.

Immunobiology of tendinopathy (14).

Figure 5.

Two immune response process in the inflammatory phase of tendinopathy (17).

Figure 5.

Two immune response process in the inflammatory phase of tendinopathy (17).

Figure 6.

The pathogenesis of tendinopathy regarding mechanical overload (12).

Figure 6.

The pathogenesis of tendinopathy regarding mechanical overload (12).

Figure 7.

Mechanisms of tendinopathy concerning inflammation (12).

Figure 7.

Mechanisms of tendinopathy concerning inflammation (12).

Figure 8.

Mechanisms of tendinopathy stemming from oxidative stress (12).

Figure 8.

Mechanisms of tendinopathy stemming from oxidative stress (12).