Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

02 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- Our study population were Roma pregnant mothers aged 18 to 35 years old.

- Their BMI at the beginning of pregnancy and after the completion of pregnancy did not exceed the index of 30.

- Mothers with pre-existing diabetes were excluded.

- Samples and data from non-Roma volunteers of European decent with the same age and BMI, served as the control group.

2.2. Methods

- Fasting glucose and insulin samples from the women’s plasma were used to determine the HOMA-IR index, to determine insulin resistance.

- Data was collected from the medical history of women and their newborns from the Hospital’s archives, and anthropometric data were obtained from women who became pregnant within the study period.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Study

3.1.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Population (Table 1)

- Data from 65 women were collected, with mean age 26.2 years (SD=5.7 years). Almost half of them (49.2%) were controls, and the rest (50.8%) were ROMA mothers.

- Women’s demographical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

- The number of children was significantly greater in the ROMA group (p=0.028), as well as the percentage of smokers (p<0.001).

- Women in the Roma group were significantly younger than those in the Control group (p<0.001).

| Total sample (n=65; 100%) | Group | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=32; 49.2%) |

ROMA (n=33; 50.8%) |

||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Multiparous (number of children) | |||||

| 1 | 27 (41.5) | 17 (53.1) | 10 (30.3) | 0.028+ | |

| 2 | 26 (40) | 13 (40.6) | 13 (39.4) | ||

| 3-4 | 12 (18.5) | 2 (6.3) | 10 (30.3) | ||

| Abortuses history | 9 (13.8) | 5 (15.6) | 4 (12.1) | 0.733++ | |

| PCO | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ | |

| Smoking | 29 (44.6) | 3 (9.4) | 26 (78.8) | <0.001+ | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (4.6) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.1) | >0.999++ | |

| Chronic lung disease | 2 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ | |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ | |

| Chronic renal disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Immuno-compromised condition | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ | |

| Neurologic disorder | 3 (4.6) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.1) | >0.999++ | |

| Psychiatric disorder | 2 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ | |

| Autoimmune disorder | 3 (4.6) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 0.114++ | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 26.2 (5.7) | 29.9 (4.8) | 22.5 (3.9) | <0.001‡ | |

| BMI (kg/m2) before pregnancy | 22.7 (2.2) | 22.7 (2.1) | 22.7 (2.4) | 0.981‡ | |

| BMI (kg/m2) after pregnancy | 24.5 (2.6) | 24.2 (2.4) | 24.8 (2.9) | 0.333‡ | |

| Difference in BMI | 1.84 (1.5) | 1.52 (1.28) | 2.15 (1.65) | 0.095‡ | |

3.1.2. Glucose, Insulin and HOMA- IR in Roma Pregnancies Compared to Control Pregnancies

- Glucose at 0min (p=0.050), at 60min (p=0.001) and at 120min (p=0.034) was significantly lower in the Roma group.

- On the contrary, the mean fasting insulin levels were significantly higher in the Roma group ( p=0.0013)

- As a result,HOMA-IR at 3rd trimester was significantly higher in the Roma group.

3.1.3. Mean Birthweight and Breastfeeding (Table 2)

- Mean birth weight was significantly lower in the Roma group.

- The percentage of breastfeeding in the control group was 90.6% while in the Roma group was significantly lower and equal to 9.1% (p<0.001).

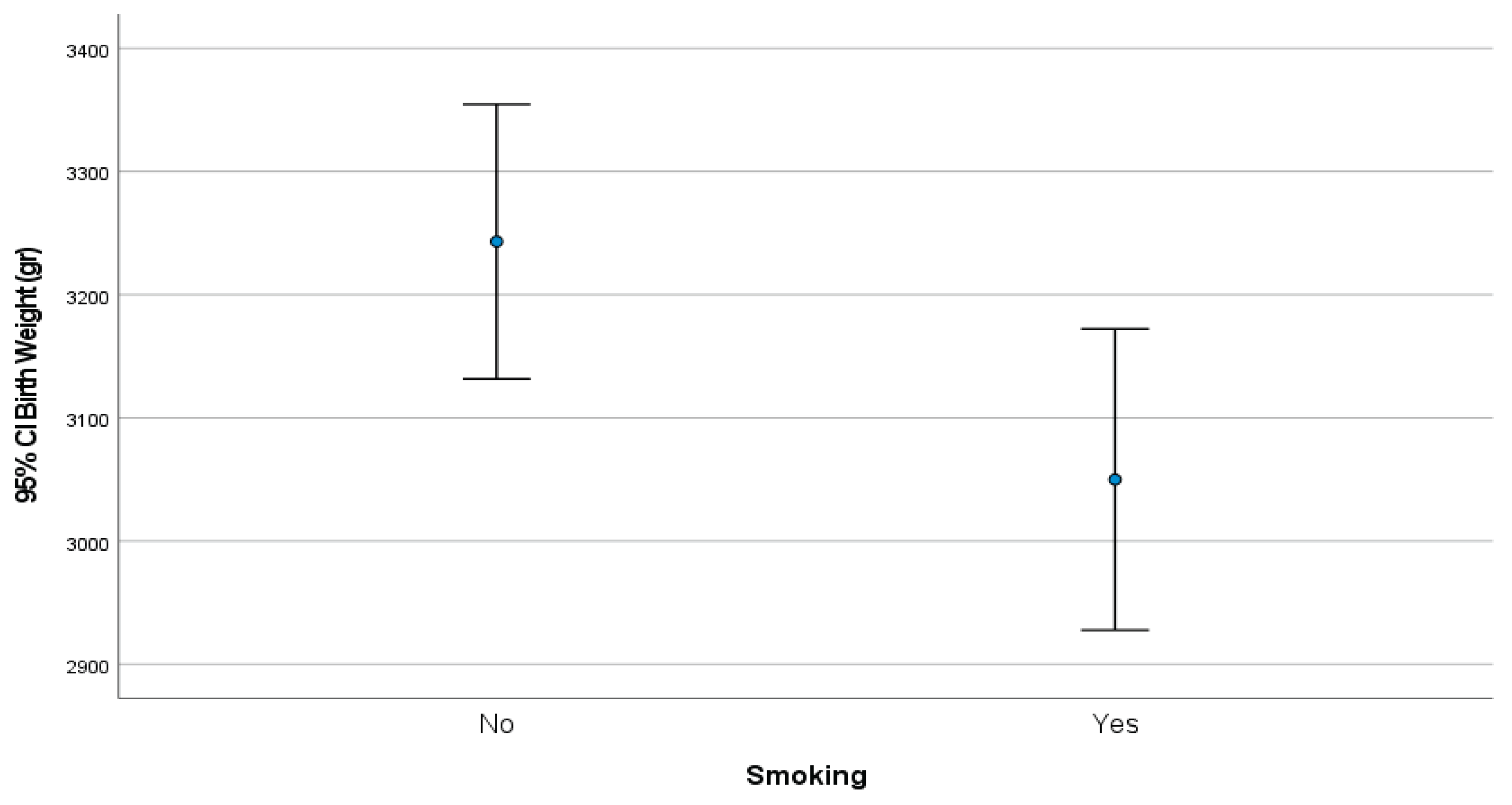

3.1.4. Mean Birthweight Correlated with Smoking Habits (Figure 1)

3.1.5. Association of Maternal Age and BMI with HOMA-IR (Table 3)

- After linear regression analysis, it emerged that age and BMI (after pregnancy) was not significantly associated with women’s HOMA-IR values (at 3rd trimester).

- On the other hand, Roma women had significantly greater HOMA-IR values, compared to controls, after adjusting for their age and after pregnancy BMI.

| β+ | SE++ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.231 |

| Groups(ROMA vs Controls) | 2.02 | 0.62 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) after pregnancy | -0.02 | 0.09 | 0.848 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment- Insulin Resistance |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Melitus |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

References

- American Diabetes Association Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S13–S27. [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 8th ed. IDF; Brussels, Belgium: 2017.

- Feig D.S., Moses R.G. Metformin Therapy during Pregnancy Good for the goose and good for the gosling too? Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2329–2330. [CrossRef]

- Butte NF. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in pregnancy: normal compared with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71(Suppl. 5): 1256S–1261S. [CrossRef]

- Catalano P.M., Tyzbir E.D., et al. Longitudinal changes in insulin release and insulin resistance in nonobese pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;165:1667–1672. [CrossRef]

- Phelps R.L., Metzger B.E., et al. Carbohydrate metabolism in pregnancy: XVII. Diurnal profiles of plasma glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, triglycerides, cholesterol, and individual amino acids in late normal pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1981;140:730–736. [CrossRef]

- Di Cianni G., Miccoli R., et al. Intermediate metabolism in normal pregnancy and in gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2003;19:259–270. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan T.A., Xiang A.H. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 2005;115:485–491.

- Plows, J., Stanley, J., et al. (2018). The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(11), 3342. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes. 2016. p. 16–8.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 2015. p. 75–87.

- The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynaecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 180, 2017.

- 14 ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes, glycaemic targets. 2017th ed. 2017.

- Ferrannini E, Mari A: How to measure insulin sensitivity. J Hypertens 16:895–906, 1998.

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, et al (1985). “Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man”. Diabetologia. [CrossRef]

- Nigatu Β., Workneh T., et al A. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic of St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology .2022; 8:2. [CrossRef]

- Fraser A: The Gypsies. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers,1992.

- Liegeois J-P: Roma, Gypsies, Travellers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Press,. 1994.

- Kalaydjieva L., Gresham D. et al. Genetic studies of the Roma (Gypsies): a review. BMC Medical Romas. 2001; 2:4. [CrossRef]

- Enache, G.; Rusu, E.; et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in the Roma Population from a County in the South Part of Romania (Călăra¸si County)-Preliminary Results. Rom. J. Diabetes Nutr. Metab. Dis. 2016, 23. [CrossRef]

- Živkovi’c, T.B.; Marjanovi’c, M.; et al . Screening for Diabetes Among Roma People Living in Serbia. Croat. Med. J. 2010, 51, 144–150.

- Piko P, Werissa NA, et al. Genetic Susceptibility to Insulin Resistance and Its Association with Estimated Longevity in the Hungarian General and Roma Populations. Biomedicines. 2022 Jul 14;10(7):1703. [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, et al Ethnicity modifies the effect of obesity on insulin resistance in pregnancy: a comparison of Asian, South Asian, and Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Jan;91(1):93-7. Epub 2005 Oct 25. PMID: 16249285. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen BT, Cheng YW, et al The effect of race/ethnicity on adverse perinatal outcomes among patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;207(4):322.e1-6. Epub 2012 Jun 29. PMID: 22818875; PMCID: PMC3462223. [CrossRef]

- Ádány R, Pikó P, et al Prevalence of Insulin Resistance in the Hungarian General and Roma Populations as Defined by Using Data Generated in a Complex Health (Interview and Examination) Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jul 4;17(13):4833. PMID: 32635565; PMCID: PMC7370128. [CrossRef]

- Nunes MA, Kučerová K, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus among Roma Populations-A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Nov 21;15(11):2607. PMID: 30469436; PMCID: PMC6265881. [CrossRef]

- Llanaj E, Vincze F, et al. Dietary Profile and Nutritional Status of the Roma Population Living in Segregated Colonies in Northeast Hungary. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 16;12(9):2836. PMID: 32947945; PMCID: PMC7551568. [CrossRef]

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gestational-diabetes.

- LeMasters K, Baber Wallis A, et al Pregnancy experiences of women in rural Romania: understanding ethnic and socioeconomic disparities. Cult Health Sex. 2019 Mar;21(3):249-262. Epub 2018 May 15. PMID: 29764305; PMCID: PMC6237651. [CrossRef]

- Bejenariu, Simona & Mitrut, Andreea, 2014. “Bridging the Gap for Roma Women: The Effects of a Health Mediation Program on Roma Prenatal Care and Child Health,” Working Papers in Economics 590, University of Gothenburg, Department of Economics.

- Retnakaran R, Qi Y, et al. Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and future risk of pre-diabetes or diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008 Oct;31(10):2026-31. Epub 2008 Jul 15. PMID: 18628572; PMCID: PMC2551649. [CrossRef]

| Total sample (n=65; 100%) | Group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=32; 49.2%) |

ROMA (n=33; 50.8%) |

|||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Glucose (0min) | 82.3 (7.4) | 84.1 (6.6) | 80.5 (7.9) | 0.050‡ |

| Glucose (60min) | 136.4 (28.6) | 147.8 (21.8) | 125.3 (30.3) | 0.001‡ |

|

Glucose (120min) Fasting Insulin |

117.4 (23.5) 15.11(8.87) |

123.6 (19.7) 11.6(6.49) |

111.3 (25.6) 18.63(7.74) |

0.034‡ 0.0013‡ |

| HOMA IR (3rd trimester) | 3.1 (2) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.9 (2.3) | 0.002‡ |

| Birth Weight (gr) | 3157 (337.5) | 3275.5 (323.4) | 3042.1 (314.4) | 0.004‡ |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| HBCA1 (1st trimester) | 5 (4.4 ─5.2) | 5 (4.4 ─5.2) | 4.8 (4.3 ─5.2) | 0.782‡‡ |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Pathological glucose curve | 7 (10.8) | 2 (6.3) | 5 (15.2) | 0.427++ |

| Gestational diabetes | 7 (10.8) | 2 (6.3) | 5 (15.2) | 0.427++ |

| Gestational hypertension | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) | 0.238++ |

| Preeclampsia | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | 0.492++ |

| Gestational age at delivery | ||||

| 35-36w | 4 (6.2) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (9.1) | 0.366++ |

| 37-38w | 10 (15.4) | 3 (9.4) | 7 (21.2) | |

| 39-40w | 35 (53.8) | 20 (62.5) | 15 (45.5) | |

| >40w | 16 (24.6) | 8 (25) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Delivery mode | ||||

| Cesarian | 28 (43.1) | 11 (34.4) | 17 (51.5) | 0.163+ |

| Vaginal | 37 (56.9) | 21 (65.6) | 16 (48.5) | |

| 5 min Apgar score <4 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ |

| Neonatal sepsis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Trauma during labour | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Low birth weight | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | >0.999++ |

| respiratory distress | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | 0.492++ |

| neonatal convulsions | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Neonatal death after delivery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Hypoglycemia | 6 (9.2) | 1 (3.1) | 5 (15.2) | 0.197++ |

| Jaundice | 13 (20) | 5 (15.6) | 8 (24.2) | 0.385+ |

| Breastfeeding | 32 (49.2) | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.1) | <0.001+ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).