Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

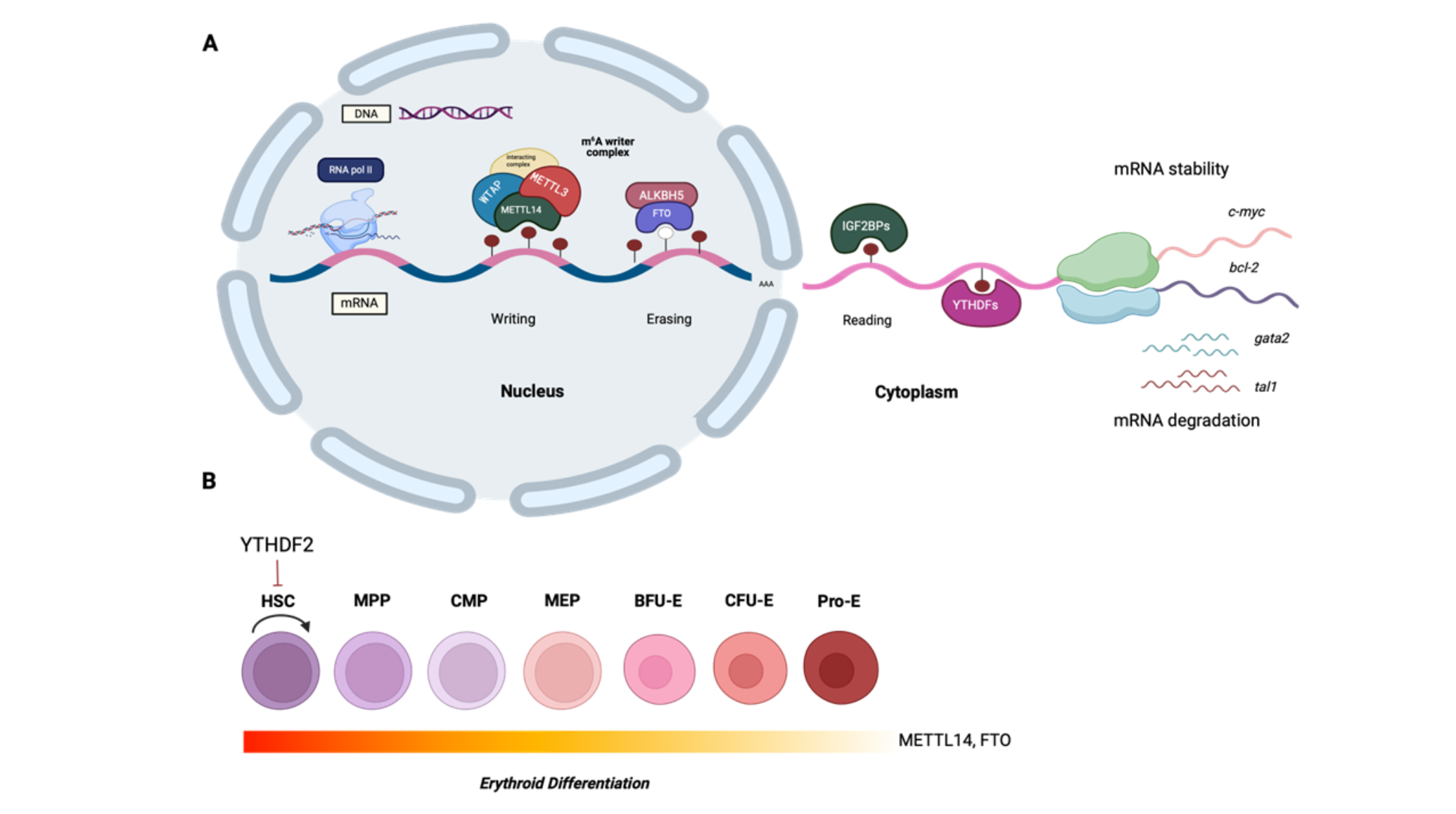

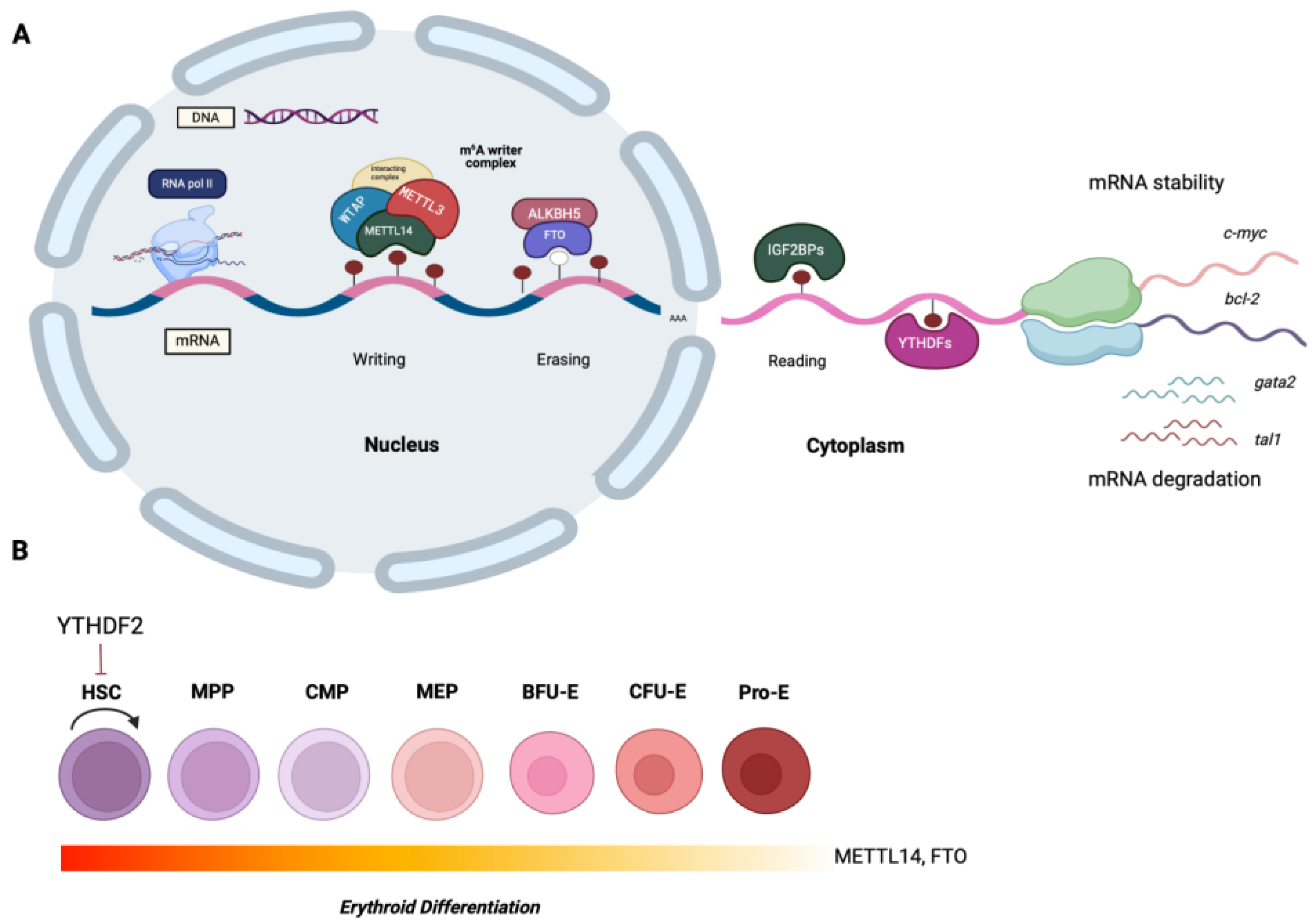

1.1. The Biochemistry of N6-methyladenosine RNA Modification

2. The Role of m6A RNA Methylation in Normal Hematopoiesis and in Disease

2.1. HSCs and Endothelial-to-Hematopoietic Transition

2.2. HSC Self-Renewal and Expansion

2.3. Erythropoiesis

2.4. Ineffective Erythropoiesis and Apoptosis

2.5. The Role of m6A Modification in Thalassemia

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kasper DM, Nicoli S. Epigenetic and epitranscriptomic factors make a mark on hematopoietic stem cell development. Curr Stem Cell Rep. 2018; 4(1):22-32. [CrossRef]

- Yue Y, Liu J, He C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015; 29(13):1343-1355. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Geng X, Li Q, et al. m6A modification in RNA: biogenesis, functions and roles in gliomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020; 39:192. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Liu B, Nie Z, et al. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021; 6(1):74. [CrossRef]

- Zhu ZM, Huo FC, Pei DS. Function and evolution of RNA N6-methyladenosine modification. Int J Biol Sci. 2020; 16(11):1929-1940. [CrossRef]

- VU P, Cheng Y, Kharas G. The biology of m6A RNA methylation in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Cancer Discov. 2019; 9(1):25-33/.

- Rieger MA, Schroeder T. Hematopoiesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012; 4(12):a008250.

- Gekas C, Rhodes KE, Van Handel B, Chhabra A, Ueno M, Mikkola HK. Hematopoietic stem cell development in the placenta. Int J Dev Biol. 2010; 54(6-7):1089-98. [CrossRef]

- Ottersbach K. Endothelial-to-haematopoietic transition: an update on the process of making blood. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019; 47(2):591-601. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Chen Y, Sun B, et al. m6A modulates haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell specification. Nature. 2017; 549(7671):273-276. [CrossRef]

- Lv J, Zhang Y, Gao S et al. Endothelial-specific m6A modulates mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell development via Notch signaling. Cell Res. 2018; 28:249–252. [CrossRef]

- Grinenko T, Eugster A, Thielecke L, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into restricted myeloid progenitors before cell division in mice. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:1898. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Zuo H, Liu J, et al. Loss of YTHDF2-mediated m6A-dependent mRNA clearance facilitates hematopoietic stem cell regeneration. Cell Res. 2018; 28(10):1035-1038. [CrossRef]

- Mapperley C, van de Lagemaat LN, Lawson H, et al. The mRNA m6A reader YTHDF2 suppresses proinflammatory pathways and sustains hematopoietic stem cell function. J Exp Med. 2021; 218(3):e20200829. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Qian P, Shao W, et al. Suppression of m6A reader Ythdf2 promotes hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Cell Res. 2018; 28(9):904-917. [CrossRef]

- Sheng Y, Wei J, Yu F, et al. A critical role of nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 in Leukemogenesis by Regulating MCM Complex-Mediated DNA Replication Blood. 2021; blood.2021011707. [CrossRef]

- Yin R, Chang J, Li Y, et al. Differential m6A RNA landscapes across hematopoiesis reveal a role for IGF2BP2 in preserving hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29(1):149-159. [CrossRef]

- Yao QJ, Sang L, Lin M et al. Mettl3-Mettl14 methyltransferase complex regulates the quiescence of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Res. 2018; 28(9):952-954. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Bao S, Qian Y, et al. Stage-specific requirement for Mettl3-dependent m6A mRNA methylation during haematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2019; 21(6):700-709. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Luo H, Izzo F, et al. m6A RNA methylation maintains hematopoietic stem cell identity and symmetric commitment. Cell Rep. 2019; 28(7):1703-1716. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Vasic R, Song Y, et al. m6A modification prevents Formation of endogenous double-Stranded RNAs and deleterious innate immune responses during hematopoietic development. Immunity. 2020; 16; 52(6):1007-1021. [CrossRef]

- Dzierzak E, Philipsen S. Erythropoiesis: development and differentiation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013; 3(4):a011601.

- Valent P, Büsche G, Theurl I, et al. Normal and pathological erythropoiesis in adults: from gene regulation to targeted treatment concepts. Haematologica. 2018; 103(10):1593-1603. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H, Zheng Z, Cheng T. New paradigms on hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Protein Cell. 2020; 11(1):34-44. [CrossRef]

- Scharf P, Broering MF, Oliveira da Rocha GH, Farsky SHP. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of environmental pollutants on hematopoiesis. Int JMol Sci. 2020; 21(19):6996. [CrossRef]

- Kuppers DA, Arora S, Lim Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine mRNA marking promotes selective translation of regulons required for human erythropoiesis. Nat Commun. 2019; 10:4596. [CrossRef]

- Barbarani G, Fugazza C, Strouboulis J, Ronchi AE. The pleiotropic effects of GATA1 and KLF1 in physiological erythropoiesis and in dyserythropoietic disorders. Front Physiol. 2019; 10:91. [CrossRef]

- Tallack MR, Perkins AC. KLF1 directly coordinates almost all aspects of terminal erythroid differentiation. IUBMB Life. 2010; 62(12):886-890. [CrossRef]

- Lithanatudom P, Leecharoenkiat A, Wannatung T, et al. A mechanism of ineffective erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia/HbE disease. Haematologica. 2010; 95(5):716-723.

- Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, et al. The N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2017; 23(11):1369-1376. [CrossRef]

- Shen C, Sheng Y, Zhu AC, et al. RNA demethylase ALKBH5 selectively promotes tumorigenesis and cancer stem cell self-Renewal in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Stem Cell. 2020; 27(1):64-80. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Li Y, Wang P, et al. Leukemogenic chromatin alterations promote AML leukemia stem cells via a KDM4C-ALKBH5-AXL signaling axis. Cell Stem Cell. 2020; 27(1):81-97.

- Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018; 20(9):1098.

- Feng M, Xie X, Han G, et al. YBX1 is required for maintaining myeloid leukemia cell survival by regulating BCL2 stability in an m6A-dependent manner. Blood. 2021; 138(1):71-85. [CrossRef]

- Jayavelu AK, Schnöder TM, Perner F, et al. Splicing factor YBX1 mediates persistence of JAK2-mutated neoplasms. Nature. 2020; 588: 157–163. [CrossRef]

- Ye J, Wang Z, Chen X, et al. YTHDF1-enhanced iron metabolism depends on TFRC m6A methylation. Theranostics. 2020; 10(26):12072-12089. [CrossRef]

- Weng H, Huang H, Wu H, et al. METTL14 inhibits hematopoietic stem/progenitor differentiation and promotes leukemogenesis via mRNA m6A modification. Cell Stem Cell. 2018; 22(2):191-205.

- Paris J, Morgan M, Campos J, et al. Targeting the RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 selectively compromises cancer stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Stem Cell. 2019; 25(1):137-148. [CrossRef]

- Raffel GD, Mercher T, Shigematsu H, et al. Ott1 (Rbm15) has pleiotropic roles in hematopoietic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104:6001–6006.

- Niu C, Zhang J, Breslin P, et al. c-Myc is a target of RNA-binding motif protein 15 in the regulation of adult hematopoietic stem cell and megakaryocyte development. Blood. 2009; 114 (10): 2087–2096. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Wang C, Fei W, Fang X, Hu X. Epitranscriptomic m6A modification in the stem cell field and its effects on cell death and survival. Am J Cancer Res. 2019; 9(4):752-764.

- Liu S, Zhuo L, Wang J, et al. METTL3 plays multiple functions in biological processes. Am J Cancer Res. 2020; 10(6):1631-1646.

- Xu L, Zhang C, Yin H, et al. RNA modifications act as regulators of cell death. RNA Biol. 2021; 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Wang J, Tahir M, et al. Current insights into the implications of m6A RNA methylation and autophagy interaction in human diseases. Cell Biosci. 2021; 11:147. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Li Q, Li G, et al. The mechanism of m6A methyltransferase METTL3- mediated autophagy in reversing gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells by β-elemene. Cell Death Dis. 2020; 11:969. [CrossRef]

- Ruan H, Yang F, Deng L, et al. Human m6A-mRNA and lncRNA epitranscriptomic microarray reveal function of RNA methylation in hemoglobin H-Constant Spring disease. Sci Rep. 2021; 11:20478. [CrossRef]

- Liao Y, Zhang F, Yang F, et al. MRTTL16 participates in hemoglobin H disease through m6A modification. PLoS ONE 2024; 19(8):e0306043.

- Murakami S, Jaffrey S. Hidden codes in mRNA: Control of gene expression by m6A. Mol Cell. 2022; 82(12):2236-2251. [CrossRef]

- Murakami S, Olarenin-George AO, Liu JF, et al. m6A alters ribosome dynamics to initiate mRNA degradation. Cell, 2025; 188(14):3728-3743. [CrossRef]

- Corovic M, Hoch-Kraft P, Zhou Y, et al. m6A in the coding sequence: linking deposition, translation and decay. Trends Genet. 2025; S0168-9525(25)00132-5. [CrossRef]

- Sommerkamp P, Brown JA, Haltalli MLR, Mercier FE, Vu LP, Kranc KR. m6A RNA modifications: Key regulators of normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 2022;111:25-31. [CrossRef]

- Feng G, Wu Y, Hu Y, et al. Small molecule inhibitors targeting m6A regulators. J Hematol Oncol. 2024; 17:30. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).