Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

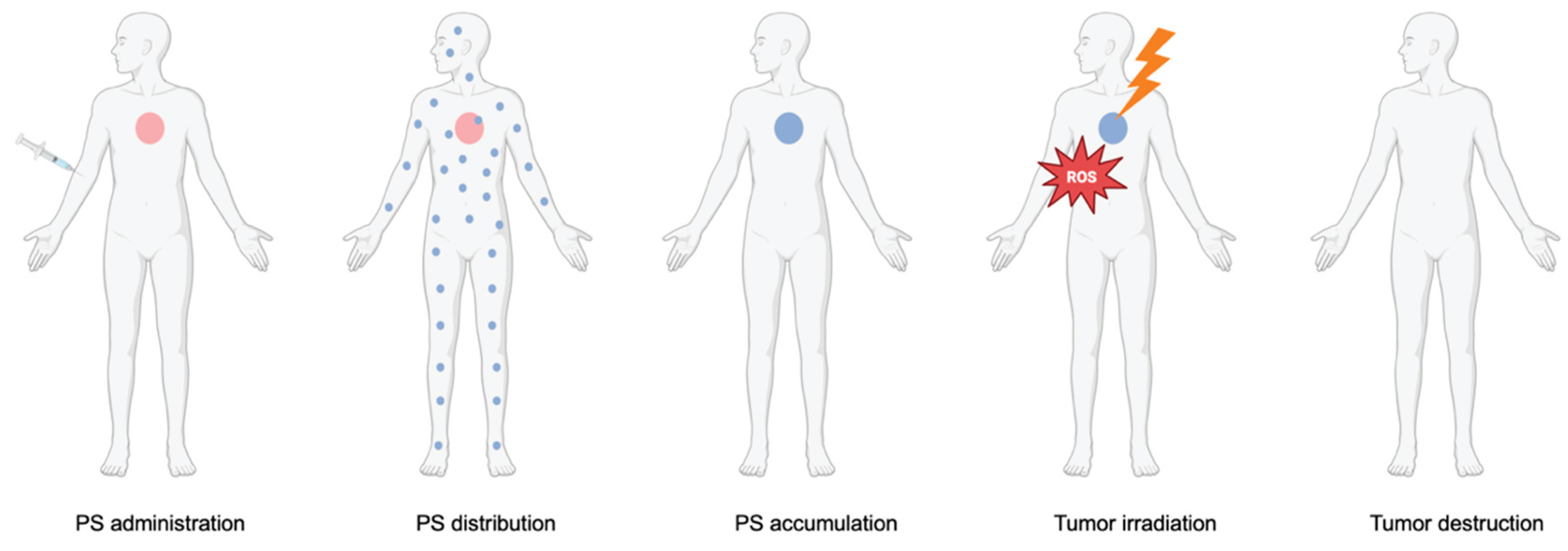

1.2. An overview of Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

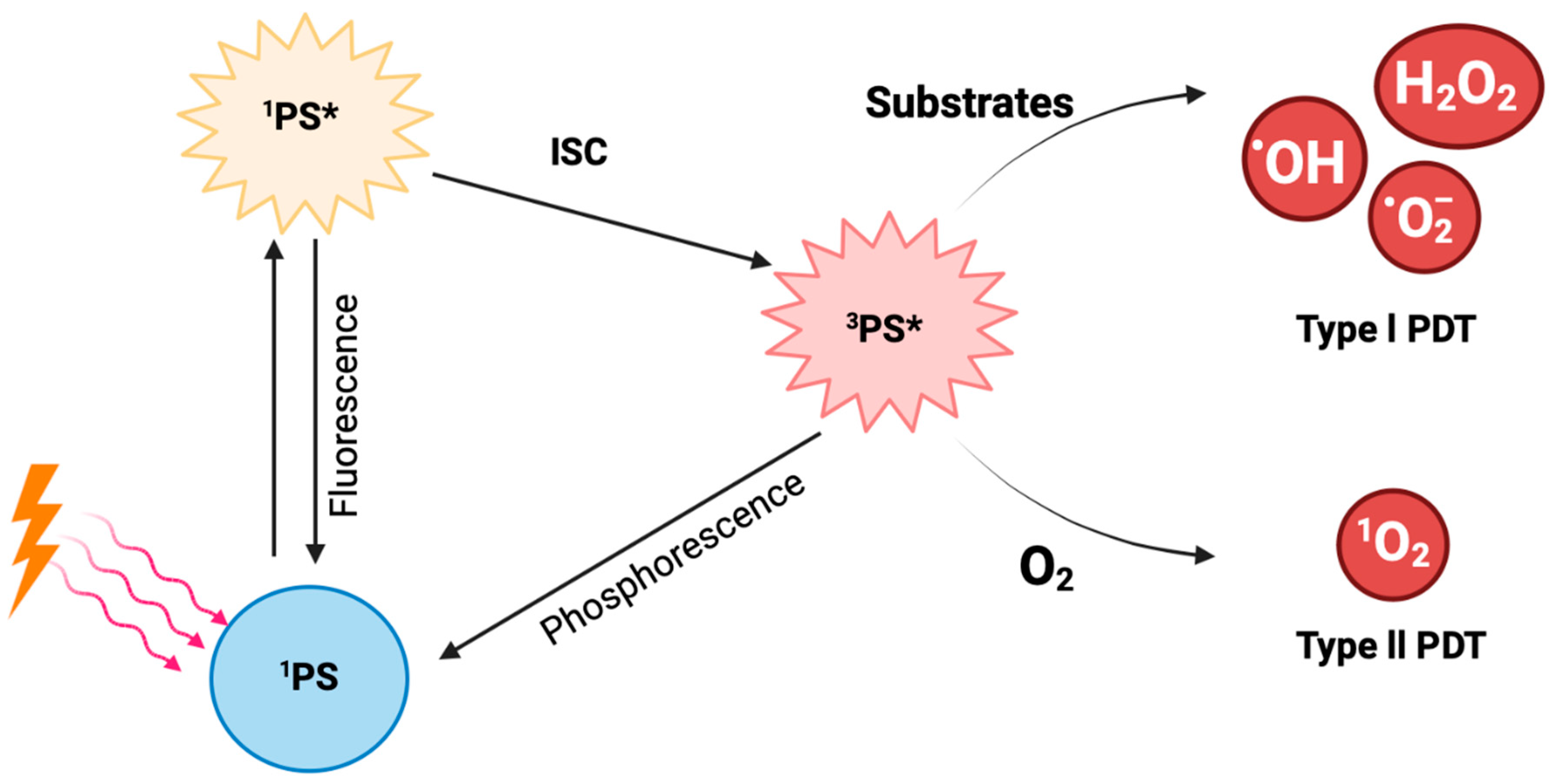

1.3. PDT’s Mechanism of Action

2. Combination of PDT with Other Therapies

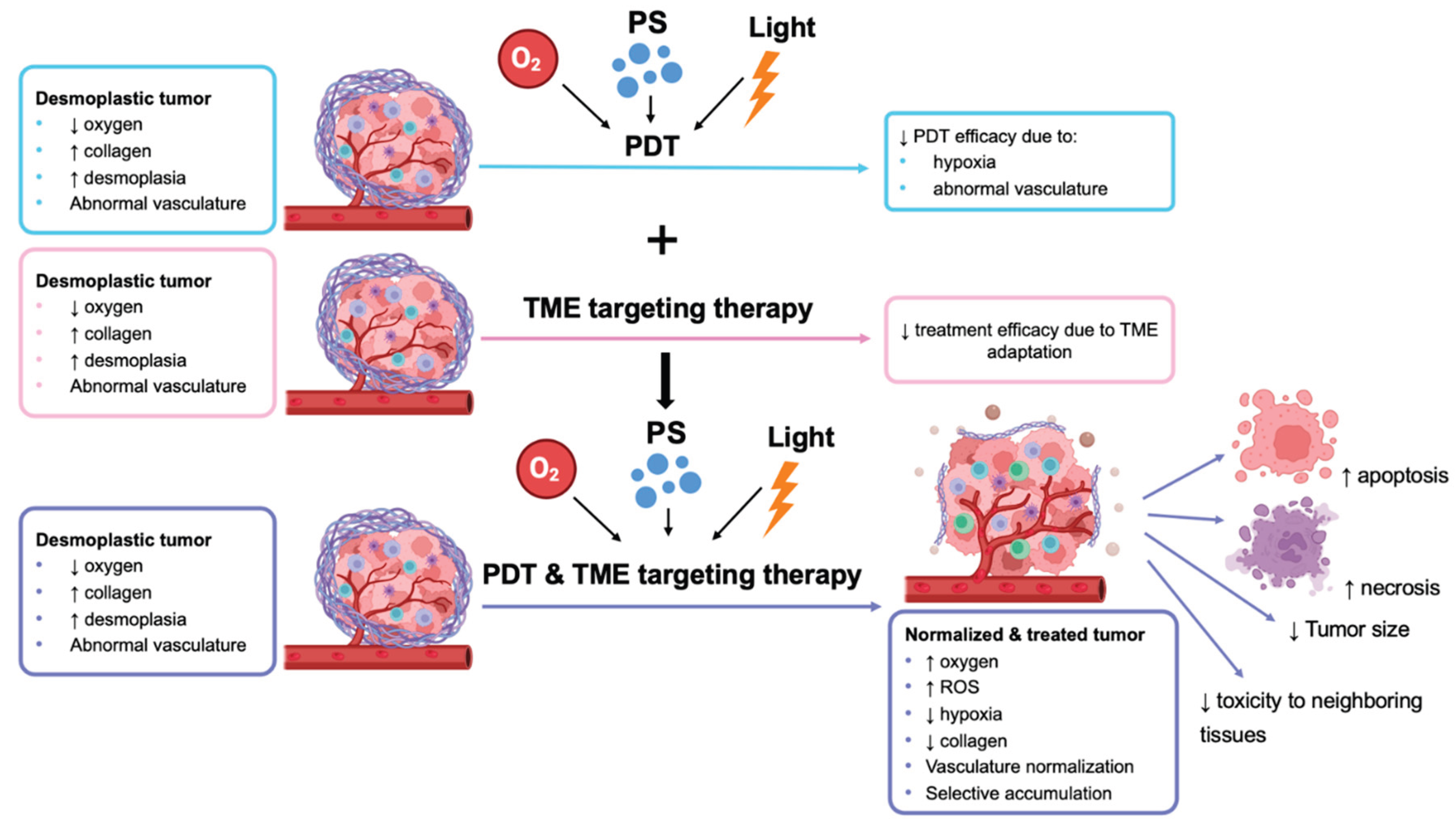

3. PDT and TME-Targeted Therapies

3.1. TME-Targeting Therapies

3.2. Combination of TME-Targeting Therapies

Targeting Hypoxia and TME Vasculature

Targeting Mitochondria and Other ECM Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Q. Wang, X. Shao, Y. Zhang, M. Zhu, F.X.C. Wang, J. Mu, J. Li, H. Yao, K. Chen, Role of tumor microenvironment in cancer progression and therapeutic strategy, Cancer Med 12 (2023) 11149. [CrossRef]

- C. Roma-Rodrigues, R. Mendes, P. V. Baptista, A.R. Fernandes, Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy, Int J Mol Sci 20 (2019). [CrossRef]

- L. Bejarano, M.J. Jordāo, J.A. Joyce, L. Bejarano, M. Jordāo, C. Author, Therapeutic Targeting of the Tumor Microenvironment, Cancer Discov 11 (2021) 933–959. [CrossRef]

- T. Therapeutics, A.E. Yuzhalin, Redefining cancer research for therapeutic breakthroughs, British Journal of Cancer 2024 130:7 130 (2024) 1078–1082. [CrossRef]

- I.I. Verginadis, D.E. Citrin, B. Ky, S.J. Feigenberg, A.G. Georgakilas, C.E. Hill-Kayser, C. Koumenis, A. Maity, J.D. Bradley, A. Lin, Radiotherapy toxicities: mechanisms, management, and future directions., Lancet 405 (2025) 338–352.

- U. Anand, A. Dey, A.K.S. Chandel, R. Sanyal, A. Mishra, D.K. Pandey, V. De Falco, A. Upadhyay, R. Kandimalla, A. Chaudhary, J.K. Dhanjal, S. Dewanjee, J. Vallamkondu, J.M. Pérez de la Lastra, Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics, Genes Dis 10 (2023) 1367–1401. [CrossRef]

- D. van Straten, V. Mashayekhi, H.S. de Bruijn, S. Oliveira, D.J. Robinson, Oncologic Photodynamic Therapy: Basic Principles, Current Clinical Status and Future Directions, Cancers (Basel) 9 (2017). [CrossRef]

- J.H. Correia, J.A. Rodrigues, S. Pimenta, T. Dong, Z. Yang, Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions, Pharmaceutics 13 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Agostinis, K. Berg, K.A. Cengel, T.H. Foster, A.W. Girotti, S.O. Gollnick, S.M. Hahn, M.R. Hamblin, A. Juzeniene, D. Kessel, M. Korbelik, J. Moan, P. Mroz, D. Nowis, J. Piette, B.C. Wilson, J. Golab, Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update, CA Cancer J Clin 61 (2011) 250–281. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Sorrin, M. Kemal Ruhi, N.A. Ferlic, V. Karimnia, W.J. Polacheck, J.P. Celli, H.C. Huang, I. Rizvi, Photodynamic Therapy and the Biophysics of the Tumor Microenvironment, Photochem Photobiol 96 (2020) 232–259. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Algorri, M. Ochoa, P. Roldán-Varona, L. Rodríguez-Cobo, J.M. López-Higuera, Photodynamic therapy: A compendium of latest reviews, Cancers (Basel) 13 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Á. Juarranz, P. Jaén, F. Sanz-Rodríguez, J. Cuevas, S. González, Photodynamic therapy of cancer. Basic principles and applications, Clinical and Translational Oncology 10 (2008) 148–154. [CrossRef]

- G. Gunaydin, M.E. Gedik, S. Ayan, Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment and Diagnosis of Cancer–A Review of the Current Clinical Status, Front Chem 9 (2021). [CrossRef]

- W. Jiang, M. Liang, Q. Lei, G. Li, S. Wu, The Current Status of Photodynamic Therapy in Cancer Treatment, Cancers (Basel) 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- R. Baskaran, J. Lee, S.G. Yang, Clinical development of photodynamic agents and therapeutic applications, Biomater Res 22 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. Kwiatkowski, B. Knap, D. Przystupski, J. Saczko, E. Kędzierska, K. Knap-Czop, J. Kotlińska, O. Michel, K. Kotowski, J. Kulbacka, Photodynamic therapy – mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 106 (2018) 1098–1107. [CrossRef]

- R. V. Huis in ‘t Veld, J. Heuts, S. Ma, L.J. Cruz, F.A. Ossendorp, M.J. Jager, Current Challenges and Opportunities of Photodynamic Therapy against Cancer, Pharmaceutics 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- R. Alzeibak, T.A. Mishchenko, N.Y. Shilyagina, I. V. Balalaeva, M. V. Vedunova, D. V. Krysko, Targeting immunogenic cancer cell death by photodynamic therapy: past, present and future, J Immunother Cancer 9 (2021) 1926. [CrossRef]

- S. Qin, Y. Xu, H. Li, H. Chen, Z. Yuan, Recent advances in in situ oxygen-generating and oxygen-replenishing strategies for hypoxic-enhanced photodynamic therapy, Biomater Sci 10 (2021) 51–84. [CrossRef]

- P.S. Maharjan, H.K. Bhattarai, Singlet Oxygen, Photodynamic Therapy, and Mechanisms of Cancer Cell Death, J Oncol 2022 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P. Nygren, What is cancer chemotherapy?, Acta Oncol (Madr) 40 (2001) 166–174. [CrossRef]

- Tateishi, S. Muramatsu, R. Kubo, E. Yonezawa, H. Kato, E. Nishida, D. Tsuruta, Efficacy and safety of bexarotene combined with photo(chemo)therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, J Dermatol 47 (2020) 443. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z. Zhang, Y. Tang, A pH-Responsive Drug Delivery System Based on Conjugated Polymer for Effective Synergistic Chemo-/Photodynamic Therapy, Molecules 28 (2023). [CrossRef]

- U. Chilakamarthi, N.S. Mahadik, D. Koteshwar, N.V. Krishna, L. Giribabu, R. Banerjee, Potentiation of novel porphyrin based photodynamic therapy against colon cancer with low dose doxorubicin and elucidating the molecular signalling pathways responsible for relapse, J Photochem Photobiol B 238 (2023) 112625. [CrossRef]

- J. Massoud, A. Pinon, M. Gallardo-Villagrán, L. Paulus, C. Ouk, C. Carrion, S. Antoun, M. Diab-Assaf, B. Therrien, B. Liagre, A Combination of Ruthenium Complexes and Photosensitizers to Treat Colorectal Cancer, Inorganics (Basel) 11 (2023) 451. [CrossRef]

- R. Dhar, A. Seethy, S. Singh, K. Pethusamy, T. Srivastava, J. Talukdar, G.K. Rath, S. Karmakar, Cancer immunotherapy: Recent advances and challenges, J Cancer Res Ther 17 (2021) 834–844. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yuan, G. Fan, H. Wu, C. Liu, Y. Zhan, Y. Qiu, C. Shou, F. Gao, J. Zhang, P. Yin, K. Xu, Photodynamic therapy synergizes with PD-L1 checkpoint blockade for immunotherapy of CRC by multifunctional nanoparticles, Molecular Therapy 29 (2021) 2931–2948. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sun, M. Zhao, W. Wang, L. Hong, Z. Wu, G. Luo, S. Lu, Y. Tang, J. Li, J. Wang, Y. Zhang, L. Zhang, 5-ALA mediated photodynamic therapy with combined treatment improves anti-tumor efficacy of immunotherapy through boosting immunogenic cell death, Cancer Lett 554 (2023) 216032. [CrossRef]

- T. Sonokawa, N. Obi, J. Usuda, Y. Sudo, T. Hamakubo, Development of a new minimally invasive phototherapy for lung cancer using antibody–toxin conjugate, Thorac Cancer 14 (2023) 645. [CrossRef]

- S. Yamashita, M. Kojima, N. Onda, M. Shibutani, In Vitro Comparative Study of Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy, Cancers (Basel) 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, Z. Cao, K. Mao, C. Wu, H. Chen, J. Wang, X. Wang, X. Cong, Y. Li, X. Meng, X. Yang, Y.G. Yang, T. Sun, Photodynamic therapy produces enhanced efficacy of antitumor immunotherapy by simultaneously inducing intratumoral release of sorafenib, Biomaterials 240 (2020) 119845. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, P. Wang, X. Wang, L. Shi, Z. Fan, G. Zhang, D. Yang, C.F. Bahavar, F. Zhou, W.R. Chen, X. Wang, Antitumor Effects of DC Vaccine With ALA-PDT-Induced Immunogenic Apoptotic Cells for Skin Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Mice, Technol Cancer Res Treat 17 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N. Trempolec, B. Doix, C. Degavre, D. Brusa, C. Bouzin, O. Riant, O. Feron, Photodynamic Therapy-Based Dendritic Cell Vaccination Suited to Treat Peritoneal Mesothelioma, Cancers (Basel) 12 (2020). [CrossRef]

- M. Vedunova, V. Turubanova, O. Vershinina, M. Savyuk, I. Efimova, T. Mishchenko, R. Raedt, A. Vral, C. Vanhove, D. Korsakova, C. Bachert, F. Coppieters, P. Agostinis, A.D. Garg, M. Ivanchenko, O. Krysko, D. V. Krysko, DC vaccines loaded with glioma cells killed by photodynamic therapy induce Th17 anti-tumor immunity and provide a four-gene signature for glioma prognosis, Cell Death Dis 13 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Korbelik, J. Banáth, W. Zhang, P. Gallagher, T. Hode, S.S.K. Lam, W.R. Chen, N-dihydrogalactochitosan as immune and direct antitumor agent amplifying the effects of photodynamic therapy and photodynamic therapy-generated vaccines, Int Immunopharmacol 75 (2019) 105764. [CrossRef]

- H.S. Hwang, K. Cherukula, Y.J. Bang, V. Vijayan, M.J. Moon, J. Thiruppathi, S. Puth, Y.Y. Jeong, I.K. Park, S.E. Lee, J.H. Rhee, Combination of Photodynamic Therapy and a Flagellin-Adjuvanted Cancer Vaccine Potentiated the Anti-PD-1-Mediated Melanoma Suppression, Cells 9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J.M. Rizzo, R.J. Segal, N.C. Zeitouni, Combination vismodegib and photodynamic therapy for multiple basal cell carcinomas, Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 21 (2018) 58–62. [CrossRef]

- R. Baskar, K.A. Lee, R. Yeo, K.W. Yeoh, Cancer and Radiation Therapy: Current Advances and Future Directions, Int J Med Sci 9 (2012) 193. [CrossRef]

- A.L. Bulin, M. Broekgaarden, D. Simeone, T. Hasan, Low dose photodynamic therapy harmonizes with radiation therapy to induce beneficial effects on pancreatic heterocellular spheroids, Oncotarget 10 (2019) 2625. [CrossRef]

- S. Mayahi, A. Neshasteh-Riz, M. Pornour, S. Eynali, A. Montazerabadi, Investigation of combined photodynamic and radiotherapy effects of gallium phthalocyanine chloride on MCF-7 breast cancer cells, Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 25 (2020) 39–48. [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, Y. Song, Z. Huang, X. Pu, Y. Wang, G. Yin, L. Gou, J. Weng, X. Meng, Photothermal photodynamic therapy and enhanced radiotherapy of targeting copolymer-coated liquid metal nanoparticles on liver cancer, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 207 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Zhou, Y. Gao, Z. Yang, N. Wang, J. Ge, X. Cao, D. Kou, Y. Gu, C. Li, M.J. Afshari, R. Zhang, C. Chen, L. Wen, S. Wu, J. Zeng, M. Gao, Biomimetic Upconversion Nanoplatform Synergizes Photodynamic Therapy and Enhanced Radiotherapy against Tumor Metastasis, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 15 (2023) 26431–26441. [CrossRef]

- B. Doix, N. Trempolec, O. Riant, O. Feron, Low photosensitizer dose and early radiotherapy enhance antitumor immune response of photodynamic therapy-based dendritic cell vaccination, Front Oncol 9 (2019) 811. [CrossRef]

- D. Yao, Y. Wang, K. Bian, B. Zhang, D. Wang, A self-cascaded unimolecular prodrug for pH-responsive chemotherapy and tumor-detained photodynamic-immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer, Biomaterials 292 (2023) 121920. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim, S.A. Kim, G.H. Nam, Y. Hong, G.B. Kim, Y. Choi, S. Lee, Y. Cho, M. Kwon, C. Jeong, S. Kim, I.S. Kim, Original research: In situ immunogenic clearance induced by a combination of photodynamic therapy and rho-kinase inhibition sensitizes immune checkpoint blockade response to elicit systemic antitumor immunity against intraocular melanoma and its metastasis, J Immunother Cancer 9 (2021) 1481. [CrossRef]

- R. Coulson, S.H. Liew, A.A. Connelly, N.S. Yee, S. Deb, B. Kumar, A.C. Vargas, S.A. O’Toole, A.C. Parslow, A. Poh, T. Putoczki, R.J. Morrow, M. Alorro, K.A. Lazarus, E.F.W. Yeap, K.L. Walton, C.A. Harrison, N.J. Hannan, A.J. George, C.D. Clyne, M. Ernst, A.M. Allen, A.L. Chand, The angiotensin receptor blocker, Losartan, inhibits mammary tumor development and progression to invasive carcinoma, Oncotarget 8 (2017) 18640. [CrossRef]

- E. Paolicchi, F. Gemignani, M. Krstic-Demonacos, S. Dedhar, L. Mutti, S. Landi, Targeting hypoxic response for cancer therapy, Oncotarget 7 (2016) 13464. [CrossRef]

- D. Fukumura, R.K. Jain, Tumor microenvironment abnormalities: Causes, consequences, and strategies to normalize, J Cell Biochem 101 (2007) 937–949. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, J. Lu, Q. You, H. Huang, Y. Chen, K. Liu, The mTOR/AP-1/VEGF signaling pathway regulates vascular endothelial cell growth, Oncotarget 7 (2016) 53269. [CrossRef]

- Y. Komohara, Y. Fujiwara, K. Ohnishi, M. Takeya, Tumor-associated macrophages: Potential therapeutic targets for anti-cancer therapy, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 99 (2016) 180–185. [CrossRef]

- R. Noy, J.W. Pollard, Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy, Immunity 41 (2014) 49–61. [CrossRef]

- G.J. Szebeni, C. Vizler, L.I. Nagy, K. Kitajka, L.G. Puskas, Pro-Tumoral Inflammatory Myeloid Cells as Emerging Therapeutic Targets, International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, Vol. 17, Page 1958 17 (2016) 1958. [CrossRef]

- C. Tulotta, P. Ottewell, The role of IL-1B in breast cancer bone metastasis, Endocr Relat Cancer 25 (2018) R421–R434. [CrossRef]

- P.M. Ridker, J.G. MacFadyen, T. Thuren, B. Everett, P. Libby, R.J. Glynn, A. Lorenzatti, H. Krum, J. Varigos, P. Siostrzonek, P. Sinnaeve, F. Fonseca, J. Nicolau, N. Gotcheva, J. Genest, H. Yong, M. Urina-Triana, D. Milicic, R. Cifkova, R. Vettus, W. Koenig, S.D. Anker, A.J. Manolis, F. Wyss, T. Forster, A. Sigurdsson, P. Pais, A. Fucili, H. Ogawa, H. Shimokawa, I. Veze, B. Petrauskiene, L. Salvador, J. Kastelein, J.H. Cornel, T.O. Klemsdal, F. Medina, A. Budaj, L. Vida-Simiti, Z. Kobalava, P. Otasevic, D. Pella, M. Lainscak, K.B. Seung, P. Commerford, M. Dellborg, M. Donath, J.J. Hwang, H. Kultursay, M. Flather, C. Ballantyne, S. Bilazarian, W. Chang, C. East, L. Forgosh, B. Harris, M. Ligueros, E. Bohula, B. Charmarthi, S. Cheng, S. Chou, J. Danik, G. McMahon, B. Maron, M.M. Ning, B. Olenchock, R. Pande, T. Perlstein, A. Pradhan, N. Rost, A. Singhal, V. Taqueti, N. Wei, H. Burris, A. Cioffi, A.M. Dalseg, N. Ghosh, J. Gralow, T. Mayer, H. Rugo, V. Fowler, A.P. Limaye, S. Cosgrove, D. Levine, R. Lopes, J. Scott, R. Hilkert, G. Tamesby, C. Mickel, B. Manning, J. Woelcke, M. Tan, S. Manfreda, T. Ponce, J. Kam, R. Saini, K. Banker, T. Salko, P. Nandy, R. Tawfik, G. O’Neil, S. Manne, P. Jirvankar, S. Lal, D. Nema, J. Jose, R. Collins, K. Bailey, R. Blumenthal, H. Colhoun, B. Gersh, Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, The Lancet 390 (2017) 1833–1842. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, W. Pang, X. Jiang, S. Ding, X. Wei, B. Gu, Light amplified oxidative stress in tumor microenvironment by carbonized hemin nanoparticles for boosting photodynamic anticancer therapy, Light: Science & Applications 2022 11:1 11 (2022) 1–16. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, H. Bai, L. Liu, F. Lv, X. Ren, S. Wang, Luminescent, Oxygen-Supplying, Hemoglobin-Linked Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Therapy, Angewandte Chemie International Edition 58 (2019) 10660–10665. [CrossRef]

- H. Lee, D.K. Dey, K. Kim, S. Kim, E. Kim, S.C. Kang, V.K. Bajpai, Y.S. Huh, Hypoxia-responsive nanomedicine to overcome tumor microenvironment-mediated resistance to chemo-photodynamic therapy, Mater Today Adv 14 (2022) 100218. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Zhu, Z. Zhang, D. He, J. Zhu, Y. Chen, Y. Zhang, Remodeling of tumor microenvironment for enhanced tumor chemodynamic/photothermal/chemo-therapy, J Nanobiotechnology 20 (2022) 388. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhu, Y. Duo, M. Suo, Y. Zhao, L. Xia, Z. Zheng, Y. Li, B.Z. Tang, Tumor-Exocytosed Exosome/Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogen Hybrid Nanovesicles Facilitate Efficient Tumor Penetration and Photodynamic Therapy, Angewandte Chemie 132 (2020) 13940–13947. [CrossRef]

- U. Chilakamarthi, N.S. Mahadik, T. Bhattacharyya, P.S. Gangadhar, L. Giribabu, R. Banerjee, Glucocorticoid receptor mediated sensitization of colon cancer to photodynamic therapy induced cell death, J Photochem Photobiol B 251 (2024) 112846. [CrossRef]

- R. Kv, T.I. Liu, I.L. Lu, C.C. Liu, H.H. Chen, T.Y. Lu, W.H. Chiang, H.C. Chiu, Tumor microenvironment-responsive and oxygen self-sufficient oil droplet nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal/photodynamic combination therapy against hypoxic tumors, Journal of Controlled Release 328 (2020) 87–99. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Liang, Y. Zheng, X.-W. Wu, C.-P. Tan, L.-N. Ji, Z.-W. Mao, J.-H. Liang, Y. Zheng, X.-W. Wu, C.-P. Tan, L.-N. Ji, Z.-W. Mao, A Tailored Multifunctional Anticancer Nanodelivery System for Ruthenium-Based Photosensitizers: Tumor Microenvironment Adaption and Remodeling, Advanced Science 7 (2020) 1901992. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, P. Wang, R. Shi, Z. Zhao, A. Xie, Y. Shen, M. Zhu, Design of the tumor microenvironment-multiresponsive nanoplatform for dual-targeting and photothermal imaging guided photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic cancer therapies with hypoxia improvement and GSH depletion, Chemical Engineering Journal 441 (2022) 136042. [CrossRef]

- Y. Peng, L. Cheng, C. Luo, F. Xiong, Z. Wu, L. Zhang, P. Zhan, L. Shao, W. Luo, Tumor microenvironment-responsive nanosystem achieves reactive oxygen species self-cycling after photothermal induction to enhance efficacy of antitumor therapy, Chemical Engineering Journal 463 (2023) 142370. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Wang, Z.X. Chen, F. Gao, C. Zhang, M.Z. Zou, J.J. Ye, X. Zeng, X.Z. Zhang, Remodeling extracellular matrix based on functional covalent organic framework to enhance tumor photodynamic therapy, Biomaterials 234 (2020) 119772. [CrossRef]

- H. Abrahamse, M.R. Hamblin, New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy, Biochem J 473 (2016) 347. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, W. Pang, X. Jiang, S. Ding, X. Wei, B. Gu, Light amplified oxidative stress in tumor microenvironment by carbonized hemin nanoparticles for boosting photodynamic anticancer therapy, Light: Science & Applications 2022 11:1 11 (2022) 1–16. [CrossRef]

| PS generation | Key characteristics | Representative PS |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Poor tissue penetration Skin hypersensitivity |

Porphyrin Hematoporphyrin |

| 2nd | Higher chemical purity Better tissue penetration Poor water solubility |

Benzoporphyrin 5-Aminolevulinic acid |

| 3rd | Higher tissue selectivity Lower required dose |

Monoclonal antibodies conjugated with PS |

| Reference | Type of cancer | Type of treatment | PDT light source | PS type | Sample | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in humans | Chemotherapy | PUVA or UVB (0.5-4.0 J/cm2 for UV-A, 0.5 2.0 J/cm2 for UV-B) |

Psoralen |

CTCL patients | Higher response rate than monotherapy with chemotherapy |

| [23] | Human breast cancer | Chemotherapy | White light (25 mW cm-2 for 30 min) |

PFE-DOX-2 |

Human breast cancer cells | powerful synergistic chemo-/PDT therapeutic effect |

| [24] | Colon cancer in mice | Chemotherapy | 1200 W lamp (20 J cm− 2, 50 mW cm− 2, 600-720nm) | P-nap 30μM for 24h |

Colon cancer cell line | Tumor regression, relapse prevention |

| [25] | Colorectal in humans | Chemotherapy | Lamp (630-660nm, 75 J/cm2) |

2H-TPyP-arene-Ru and Zn-TPyP-arene-Ru |

CRC cell lines | Cell viability decrease, increased rate of apoptosis |

| [27] | Colorectal in mice | Immunotherapy | NIR laser (660nm, 0.72 J/cm2 for 5 min) |

Temoporfin (0.3mg/kg) | Mice | Combination inhibits growth of tumors |

| [28] | Colorectal in mice and humans | Immunotherapy | Laser (635 nm, 40J/cm2, 3min) | 5-aminolevulinic acid (50 mg/kg) | Various cell lines | Combination results in tumor suppression |

| [29] | Lung cancer in humans | Immunotherapy | Laser (664nm) | mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 (NPe6) (0.1,1,3mg/kg) | Human lung cancer cells | Enhancement of antitumor effect |

| [30] | Human breast ductal carcinoma, Human epidermis carcinoma | Immunotherapy | Laser (690nm, 50 mW/cm2) |

mAb-IR700/ talaporfin Dose not available |

Various cell lines | Combination provides additive treatment effect |

| [31] | Human thyroid and breast cancer in mice | Immunotherapy | Laser (660nm, 0.05W/cm2 for 120 min) |

Chlorin (0.65mg/kg) | Mice | Strong antitumor immune response induction |

| [32] | Skin squamous cell carcinoma in mice | Immunotherapy (vaccine) | LED (630nm, 10mW/cm2, 0.5J/cm2) | 5-aminolevulinic acid (0.5mM for 5h) | Mice | ALA-PDT DC vaccine induces systemic antitumor responses |

| [33] | Peritoneal mesothelioma in mice | Immunotherapy (vaccines) | Daylight LED (2.55 mW/cm2) for 1h, 9.18 J/cm2) |

OR141 Dose not available |

Mesothelioma cell lines & mice | Induction of strong immune response against mesothelioma |

| [34] | Glioma in mice | Immunotherapy (vaccines) | Not available (20 J/cm2) |

Photosens | subcutaneous and orthotopic mouse models | Combination is effective in treating glioma |

| [35] | Squamous cell carcinoma in mice | Immunotherapy (vaccine) | Lamp (665 ± 10 nm, 1 J/cm2, 30 mW/ cm2) | Chlorin e6 (1 μg/ml) |

Mouse tumor models | Immunotherapy is an adjunct to PDT |

| [36] | Melanoma in mice | Immunotherapy (vaccine) | Laser (674nm, 200 mW/cm2 for 15 min) | pheophorbide A (PhA) (5 mg/kg) | Mouse models | Combination suppresses tumors |

| [37] | Multiple basal cell carcinomas in humans | Immunotherapy | LED lamp (630nm, 75J/cm2 for 20-24min) |

5-aminolevulinic acid Dose not available |

BCC Patients | Combination results in effective treatment of BCC |

| [39] | Pancreatic in humans | Radiotherapy | NIR laser (690nm, 150mW/cm2) | benzoporphyrin-derivative (0.25μmol/L) | PanCan cell lines | Restriction of tumor growth and increased necrosis |

| [40] | Breast in mice | Radiotherapy | Laser (660 nm, 150mW, 15.7mW/cm2, 1.8 and 2.8 J/cm2 for 120 & 180s) | GaPcCl (50-100μg/ml) | MCF-7 cells | Decreased cell survival Increased apoptosis |

| [41] | Human liver cancer in mice | Radiotherapy | NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W⋅cm− 2 for 5 min |

RGD-PEG-PAA-MN@LM (100μL) | Mice with HepG2 tumors | Increased ROS production Tumor size decrease |

| [42] | Breast in mice | Radiotherapy | NIR light (10 min, 1 min interval, 0.25 W/cm-2) | RBC/Ce6/UCNPs (0.1 mmol Gd per kg body weight | Mice with 4T1 tumors | Increased ROS production Enhancement of anti-tumor immune response |

| [43] | Squamous cell carcinoma in mice | Radiotherapy & immunotherapy | Daylight LED (2.55 mW/cm2) for 1 h, 9.18 J/cm2) | OR141 (4 and 40 nm/kg) | Mice with SCC7 tumors | Additive effect of DC vaccination peri-radiation |

| [44] | Triple-negative breast cancer in mice | Chemotherapy & immunotherapy | Not available | AIEgen Dose not available |

Cell lines and mice | Enhanced tumor suppression |

| [45] | Intraocular melanoma in mice | Immunotherapy | LED (633nm, 65 mW/cm2 for 3 min) | Chlorin (Ce6) Dose not available |

Syngeneic mouse models | Enhancement of anti-tumor immune response |

| Reference | Target | Cancer type | PS | Light source | Sample | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | TME oxidative stress | Breast in mice | Polymer encapsulated carbonized hemin nanoparticles (P-CHNPs) (8 mg kg−1, 40 μL) | Not available (400–700 nm, 100 mW cm−2, 20 min) |

Mice | Better treatment localization, Reduced tumor size |

| [56] | Hypoxia | Cervical in humans | Hemoglobin (Hb)-linked CPNs (8 mg mL-1 for 12h) | Blue light from luminol (375–550 nm) |

HeLa cells | Increased oxygen production |

| [57] | Hypoxia | Cervical in humans | Paclitaxel loaded human serum albumin nanoparticles conjugated with Azo and Ce6 (RP/CA/PHNPs) (1mg/mL, 2 days for 4h) | Laser (670nm, 150 mW/cm2 for 10 min) | HeLa cells | Tumor growth inhibition |

| [60] | Hypoxia | Colon in mice | Porphyrin based PS containing methoxy-napthalene (P-nap) 5mg/kg | Lamp 1200 W (600–720 nm, 20 J cm− 2, 50 mW cm− 2) |

Mice | Tumor suppression, increased survival |

| [61] | Hypoxia | Prostate in mice | Nanoparticles containing the PS mTHPC, IR780, Perfluorooctylbromide (PFOB@IMHNPs) Dose not available |

NIR laser (660nm for 5 min or 808nm combined with 660nm for 5 min) | Mice | Tumor growth suppression, tumor hypoxia relief |

| [62] | Hypoxia | Breast in mice | PDA-Pt-CD@RuFc NPs (200 μL, 1 mg mL−1, 4 h) | Lasers (450 nm and 808 nm, 1 W cm−2) | Mice | Hypoxia reduction, therapeutic effect enhancement |

| [63] | Hypoxia | Liver in humans | Fe3O4/Au NCs@LCPAA-TPP nanoplatform (500 μg/mL) | NIR laser (808 nm, 1.0 W⋅cm− 2 for 8 min) | Mice | Hypoxia reduction, Induction of apoptosis |

| [58] | TME vasculature |

Colorectal in mice |

AFZDA nanoparticles (0.5 mg/kg every other day for 14 days) |

NIR laser (808 nm laser at 1.5 W for 3 min) | Mice | Tumor vessel normalization |

| [59] | TME vasculature | Breast in mice | Tumor-exocytosed EXO/AIEgen hybrid nanovesicles (DES) (20 mg mL-1) | Laser (532nm, 0.5 W cm-2, 5 min) | Mice | Hypoxia reduction, tumor growth inhibition |

| [64] | Mitochondria | Colorectal in humans | MND-IR@RESV (0 mg/mL, 0.3 mg/mL, 0.6 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL) | NIR laser (808 nm at 1 W cm−2 for 5 min) | Mice | Induction of tumor cell apoptosis |

| [65] | ECM components | Colorectal in mice | PCPP (100 μL, 50 mg kg−1 for 7 days) | Laser (0.5 W cm−2, 10 min) | Mice | Tumor solid stress and hypoxia reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).