Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equations

2.2. Model input parameters

2.3. Vessel responses to transmural pressure variations

3. Results

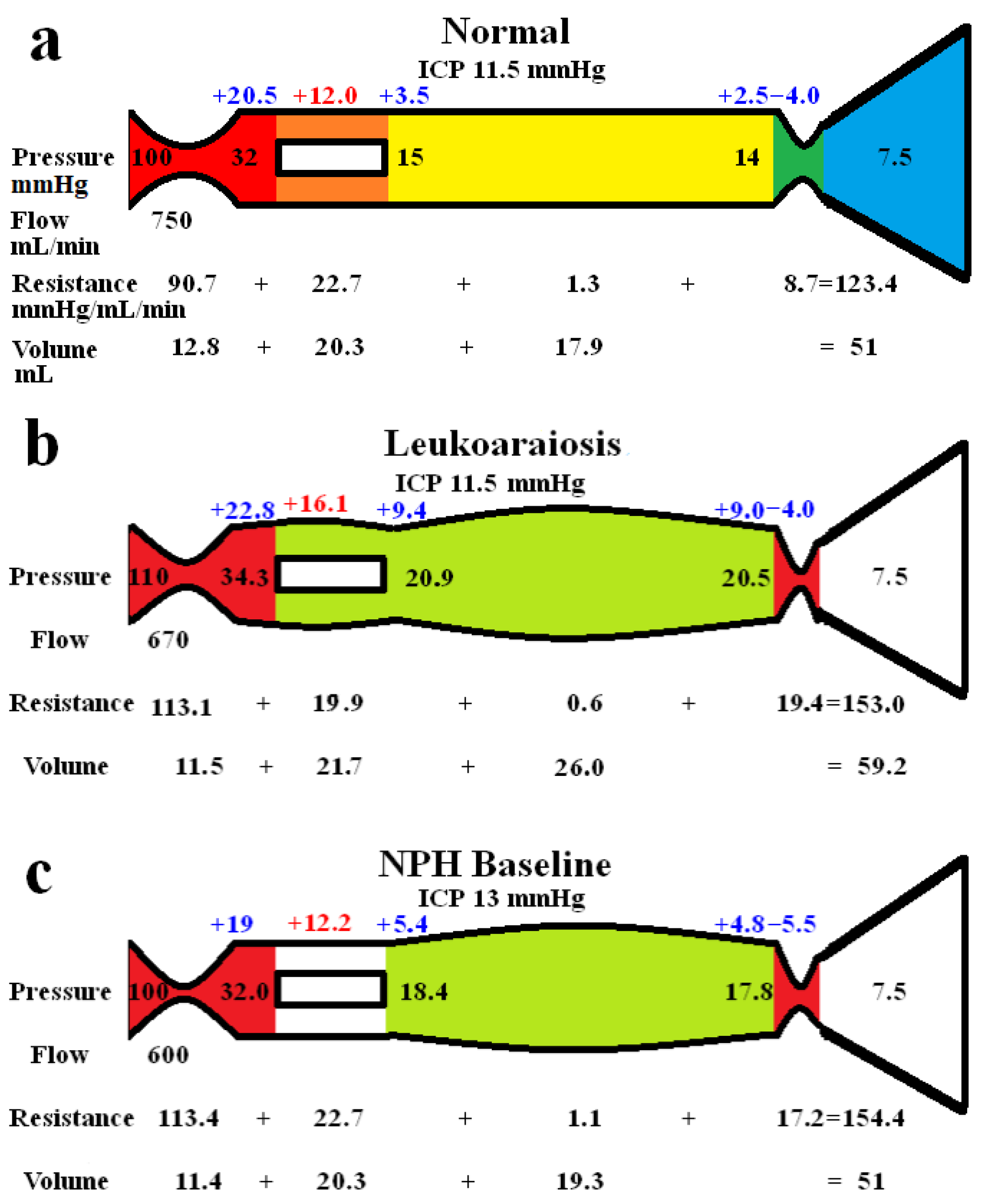

3.1. Whole brain findings

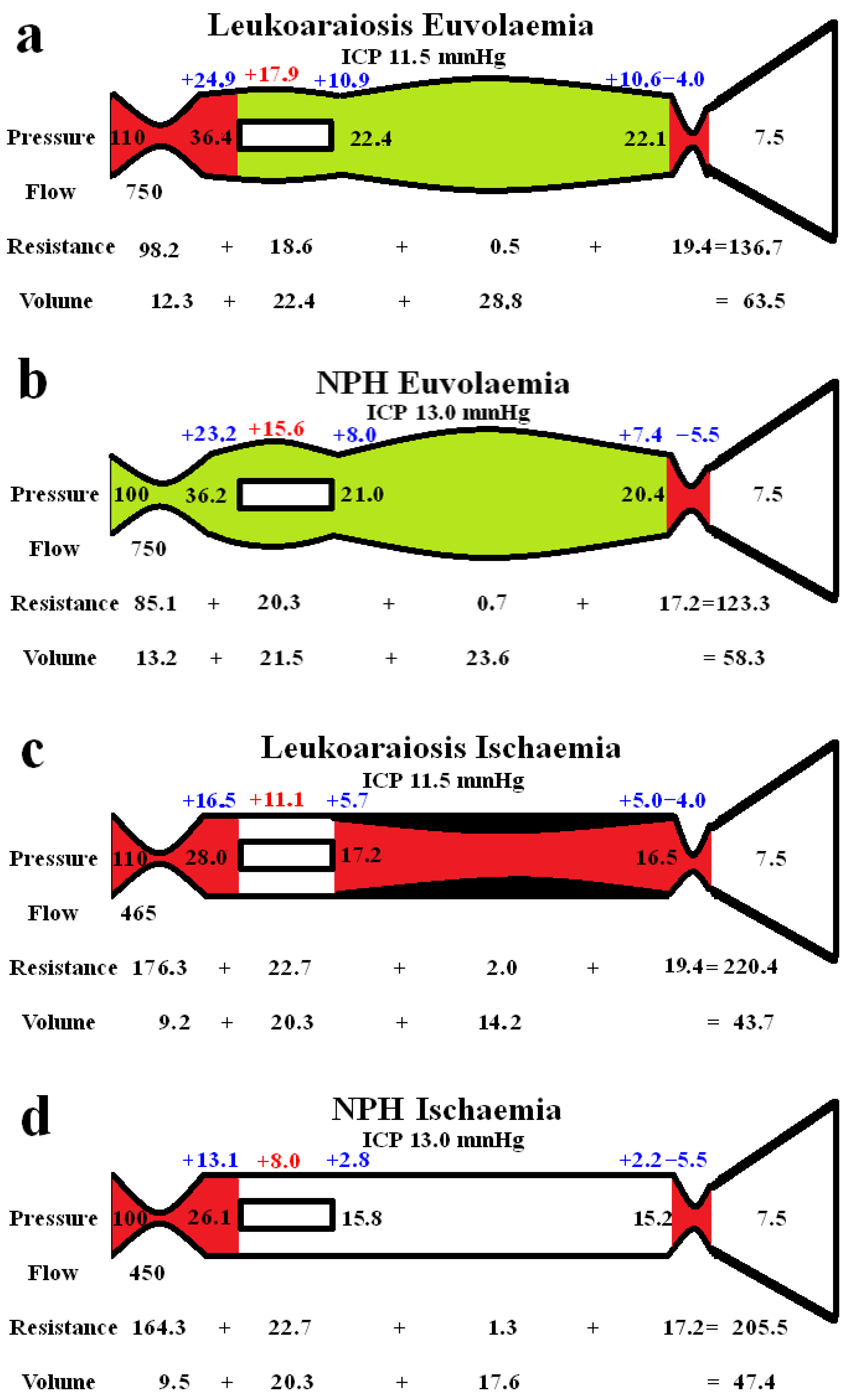

3.2. Differences between the grey and white matter

4. Discussion

4.1. Global brain changes in leukoaraiosis

4.2. Differences between the cortex and white matter

4.3. Pulsatility as a cause of leukoaraoisis

4.4. Clinical utility

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- iu, C.K.; Miller, B.L.; Cummings, J.L.; Mehringer, C.M.; Goldberg, M.A.; Howng, S.L.; Benson, D.F. A quantitative MRI study of vascular dementia. Neurology 1992, 42, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Shim, J.Y.; Lee, H.R.; Na, H.Y.; Lee, Y.J. The relationship between pulse pressure and leukoaraiosis in the elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 54, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoni, L.; Garcia, J.H. The significance of cerebral white matter abnormalities 100 years after Binswanger's report. A review. Stroke 1995, 26, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, A.; Roijer, A.; Rudling, O.; Norrving, B.; Larsson, E.M.; Eskilsson, J.; Wallin, L.; Olsson, B.; Johansson, B.B. Cerebral lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, heart disease, and vascular risk factors in subjects without stroke. A population-based study. Stroke 1994, 25, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzitari, D.; Diaz, F.; Fox, A.; Hachinski, V.C.; Steingart, A.; Lau, C.; Donald, A.; Wade, J.; Mulic, H.; Merskey, H. Vascular risk factors and leuko-araiosis. Arch. Neurol. 1987, 44, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tullberg, M.; Jensen, C.; Ekholm, S.; Wikkelso, C. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: vascular white matter changes on MR images must not exclude patients from shunt surgery. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001, 22, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. A lumped parameter modelling study of cerebral autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus suggests the brain chooses to be ischemic. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. A Lumped Parameter Model Suggests That Infusion Studies Overestimate the Cerebrospinal Fluid Outflow Resistance in Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davson, H.; Welch, K.; Segal, M.B. Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Cerebrospinal Fluid; Churchill Livingstone: 1987.

- Zislin, V.; Rosenfeld, M. Impedance Pumping and Resonance in a Multi-Vessel System. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursino, M. A mathematical study of human intracranial hydrodynamics. Part 1--The cerebrospinal fluid pulse pressure. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1988, 16, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.H.; Timperman, A.L. Effect of intracranial hypotension on cerebral blood flow. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1971, 34, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, S.; Walsh, C.; Fraser, W.D. Mathematical study of the role of non-linear venous compliance in the cranial volume-pressure test. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2003, 41, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, D.; Berdahl, J.P.; Zaydlarova, J.; Stinnett, S.; Fautsch, M.P.; Allingham, R.R. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure decreases with older age. PLoS One 2012, 7, e52664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.L.; De Rougemont, J.; Barge, M. [Cerebral venous pressure, sinus pressure and intracranial pressure]. Neurochirurgie 1974, 20, 623–632. [Google Scholar]

- Pollay, M. The function and structure of the cerebrospinal fluid outflow system. Cerebrospinal Fluid. Res. 2010, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A.; Siddique, S.H. Cerebrospinal fluid absorption block at the vertex in chronic hydrocephalus: obstructed arachnoid granulations or elevated venous pressure? Fluids Barriers CNS 2014, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I.H.; Rowan, J.O. Raised intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow. 3. Venous outflow tract pressures and vascular resistances in experimental intracranial hypertension. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1974, 37, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Liu, P.; Kim, T.; Donahue, M.; Rane, S.; Chen, J.J.; Qin, Q.; Kim, S.G. MRI techniques to measure arterial and venous cerebral blood volume. Neuroimage 2019, 187, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez González, M. CNS Compartments: The Anatomy and Physiology of the Cerebrospinal Fluid. In Liquorpheresis: Cerebrospinal Fluid Filtration to Treat CNS Conditions, Menéndez González, M., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Qvarlander, S.; Sundstrom, N.; Malm, J.; Eklund, A. CSF formation rate-a potential glymphatic flow parameter in hydrocephalus? Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassen, J.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Panerai, R.B.; Faraci, F.M. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1487–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duelli, R.; Kuschinsky, W. Changes in brain capillary diameter during hypocapnia and hypercapnia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 1993, 13, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, D.E.S.; Ranieri, A.; Bonavita, V. Starling resistors, autoregulation of cerebral perfusion and the pathogenesis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Panminerva Med. 2017, 59, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.S.; Lythgoe, D.J.; Ostegaard, L.; O'Sullivan, M.; Williams, S.C. Reduced cerebral blood flow in white matter in ischaemic leukoaraiosis demonstrated using quantitative exogenous contrast based perfusion MRI. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. Brain Ischemia in Alzheimer’s Disease May Partly Counteract the Disruption of the Blood–Brain Barrier. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. A Lumped Parameter Modelling Study of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Suggests the CSF Formation Rate Varies with the Capillary Transmural Pressure. Brain Sci. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sadoshima, S.; Ibayashi, S.; Kuwabara, Y.; Ichiya, Y.; Fujishima, M. Leukoaraiosis and dementia in hypertensive patients. Stroke 1992, 23, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, C.D.; Johnsrude, I.; Ashburner, J.; Henson, R.N.; Friston, K.J.; Frackowiak, R.S. Cerebral asymmetry and the effects of sex and handedness on brain structure: a voxel-based morphometric analysis of 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage 2001, 14, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wan, J.; Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Zhao, S.; Sun, J.; Lin, Y.; Shen, C.; Lou, M. Increased visibility of deep medullary veins in leukoaraiosis: a 3-T MRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Huang, K.; Yang, F.; He, J.; Hu, N.; Gao, H.; Feng, S.; Qin, L.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; et al. The contribution of cerebral small vessel disease in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: Insights from a prospective cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e14395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatazawa, J.; Shimosegawa, E.; Satoh, T.; Toyoshima, H.; Okudera, T. Subcortical hypoperfusion associated with asymptomatic white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke 1997, 28, 1944–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, J.; Perkio, J.; Soinne, L.; Ostergaard, L.; Carano, R.A.; Salonen, O.; Savolainen, S.; Kaste, M.; Aronen, H.J.; Tatlisumak, T. Cerebral hemodynamics in a healthy population measured by dynamic susceptibility contrast MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 2003, 44, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinnutt, C.L.; Saha, B. Cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine 2005, 6, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, A.L.; Gutierrez, J.; Gao, F.; Igwe, K.C.; Colon, J.M.; Black, S.E.; Brickman, A.M. Increased Diameters of the Internal Cerebral Veins and the Basal Veins of Rosenthal Are Associated with White Matter Hyperintensity Volume. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 1712–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Tu, X.; Lin, Q.; Zhan, Z.; Tang, L.; Liu, J. Increased internal cerebral vein diameter is associated with age. Clin. Imaging 2021, 78, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoni, L.; Inzitari, D.; Pracucci, G.; Lolli, F.; Giordano, G.; Bracco, L.; Amaducci, L. Cerebrospinal fluid proteins in patients with leucoaraiosis: possible abnormalities in blood-brain barrier function. J. Neurol. Sci. 1993, 115, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uh, J.; Yezhuvath, U.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, H. In vivo vascular hallmarks of diffuse leukoaraiosis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2010, 32, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, m.m.; Pelz, D.M.; Hachinski, V. Proceedings of the Association of British Neurologists and the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, Bristol, 4-6 April 1990. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1990, 53, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuta, J.; Kamagata, K.; Taoka, T.; Takabayashi, K.; Uchida, W.; Saito, Y.; Andica, C.; Wada, A.; Kawamura, K.; Akiba, C.; et al. Water Diffusivity Changes Along the Perivascular Space After Lumboperitoneal Shunt Surgery in Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 843883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabayan, B.; Westendorp, R.G.J. Neurovascular-glymphatic dysfunction and white matter lesions. Geroscience 2021, 43, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, D.M.; Brown, W.R.; Challa, V.R.; Anderson, R.L. Periventricular venous collagenosis: association with leukoaraiosis. Radiology 1995, 194, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, J.; Gao, F.Q.; Noor, R.; Kiss, A.; Balasubramaniam, G.; Au, K.; Rogaeva, E.; Masellis, M.; Black, S.E. Collagenosis of the Deep Medullary Veins: An Underrecognized Pathologic Correlate of White Matter Hyperintensities and Periventricular Infarction? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Kimura, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Yoshinaga, S.; Tomonaga, M. Cerebral blood flow and autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 1997, 40, 1161–1165, discussion 1165-1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. A Lumped Parameter Modelling Study of Cerebral Autoregulation in Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: Does the Brain choose to be Ischemic? Research Square 2024, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, F.; Kleinert, R.; Offenbacher, H.; Schmidt, R.; Kleinert, G.; Payer, F.; Radner, H.; Lechner, H. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology 1993, 43, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, M.Y.; Mao, C.H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.Y.; Qian, X.J.; Ma, C.; Qiu, W.Y.; Zhu, Y.C. Arteriolosclerosis differs from venular collagenosis in relation to cerebrovascular parenchymal damages: an autopsy-based study. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2023, 8, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahna, D.; Schwartz, D.L.; Woltjer, R.; Black, S.E.; Roese, N.; Dodge, H.; Boespflug, E.L.; Keith, J.; Gao, F.; Ramirez, J.; et al. Venous Collagenosis as Pathogenesis of White Matter Hyperintensity. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 92, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Thrippleton, M.J.; Makin, S.D.; Marshall, I.; Geerlings, M.I.; de Craen, A.J.M.; van Buchem, M.A.; Wardlaw, J.M. Cerebral blood flow in small vessel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2016, 36, 1653–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A. Pulse wave encephalopathy: a spectrum hypothesis incorporating Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and normal pressure hydrocephalus. Med. Hypotheses 2004, 62, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.J.; Simoni, M.; Mazzucco, S.; Kuker, W.; Schulz, U.; Rothwell, P.M. Increased cerebral arterial pulsatility in patients with leukoaraiosis: arterial stiffness enhances transmission of aortic pulsatility. Stroke 2012, 43, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A. Pulse-wave encephalopathy: a comparative study of the hydrodynamics of leukoaraiosis and normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neuroradiology 2002, 44, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A.; Levi, C.R.; Schofield, P.; Wang, Y.; Lovett, E.C. The venous manifestations of pulse wave encephalopathy: windkessel dysfunction in normal aging and senile dementia. Neuroradiology 2008, 50, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephensen, H.; Tisell, M.; Wikkelso, C. There is no transmantle pressure gradient in communicating or noncommunicating hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2002, 50, 763–771, discussion 771-763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Pieniek, M.; Fard, A.; O'Brien, J.; Mannion, J.D.; Zalewski, A. Adventitial remodeling after coronary arterial injury. Circulation 1996, 93, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R.; Subramanian, G.M. Dilatation of the bridging cerebral cortical veins in childhood hydrocephalus suggests a malfunction of venous impedance pumping. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnoy, H.D.; Chopp, M.; Branch, C.; Shannon, M.B. Cerebrospinal fluid pulse waveform as an indicator of cerebral autoregulation. J. Neurosurg. 1982, 56, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Luan, L.; Kong, D.; Zhao, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Yu, T.; Pang, Q. MRI-based investigation on outflow segment of cerebral venous system under increased ICP condition. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2008, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Nornes, H.; Aaslid, R.; Lindegaard, K.F. Intracranial pulse pressure dynamics in patients with intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1977, 38, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachani, N.; Vijay, S.; Vyas, A.; Jadwani, J.; Panicker, G.; Lokhandwala, Y. The diastolic duration as a percentage of the cardiac cycle in healthy adults: A pilot study. Indian. Heart J. 2025, 77, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, G.A.; Ahire, C.; Csipo, T.; Tarantini, S.; Kiss, T.; Balasubramanian, P.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Farkas, E.; Toth, A.; Nyul-Toth, A.; et al. Cerebral venous congestion promotes blood-brain barrier disruption and neuroinflammation, impairing cognitive function in mice. Geroscience 2019, 41, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A. Pulse wave myelopathy: An update of an hypothesis highlighting the similarities between syringomyelia and normal pressure hydrocephalus. Med. Hypotheses 2015, 85, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Yokota, A.; Haratake, J.; Horie, A. Morphological study of experimental syringomyelia with kaolin-induced hydrocephalus in a canine model. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 84, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koueik, J.; DeSanti, R.L.; Iskandar, B.J. Posterior fossa decompression for children with Chiari I malformation and hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2022, 38, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Diehl, J.; Sklar, F.H. Subtemporal decompressions for shunt-dependent ventricles: mechanism of action. Surg. Neurol. 1983, 19, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. Is the ischemia found in normal pressure hydrocephalus secondary to venous compression or arterial constriction? A comment on Ohmura et al. Fluids Barriers CNS 2025, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).