Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Audiovisual Media and Social Construction

1.2. Representation and Discourse in Audiovisual Works

1.3. Theoretical Models of Disability and Their Impact on Representation

1.4. Need for a Scoping Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framework

2.2. Identification of Research Questions

2.3. Search Strategy

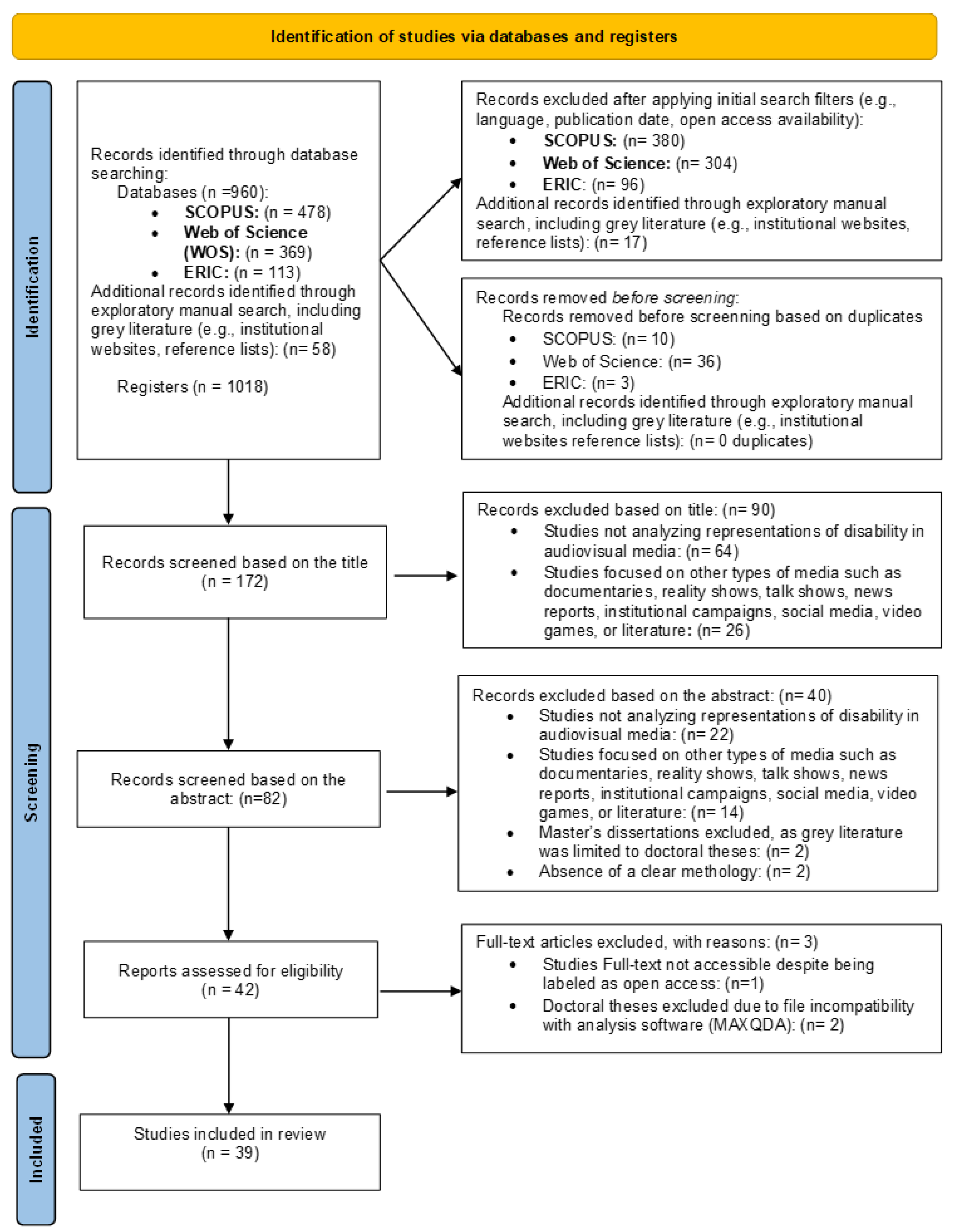

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Selection and Extraction

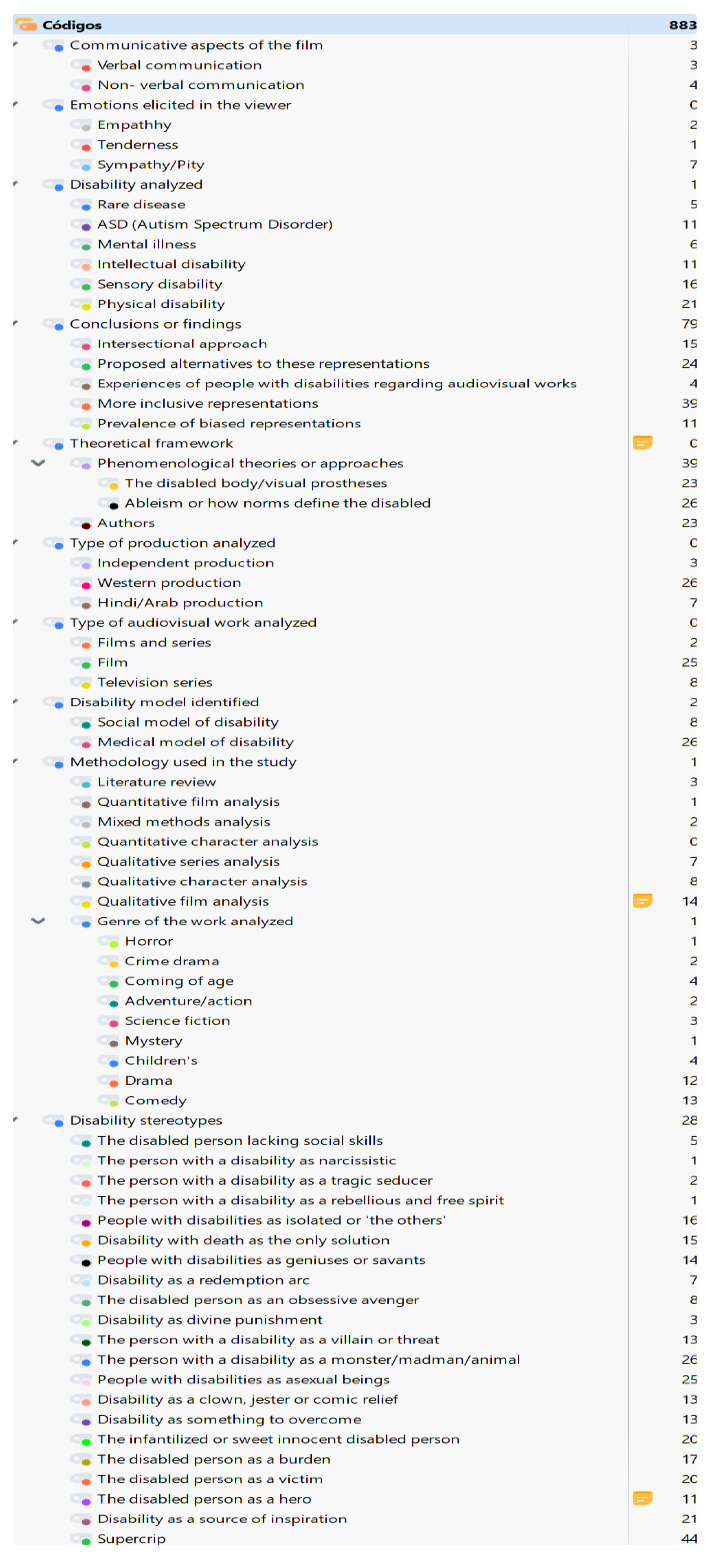

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

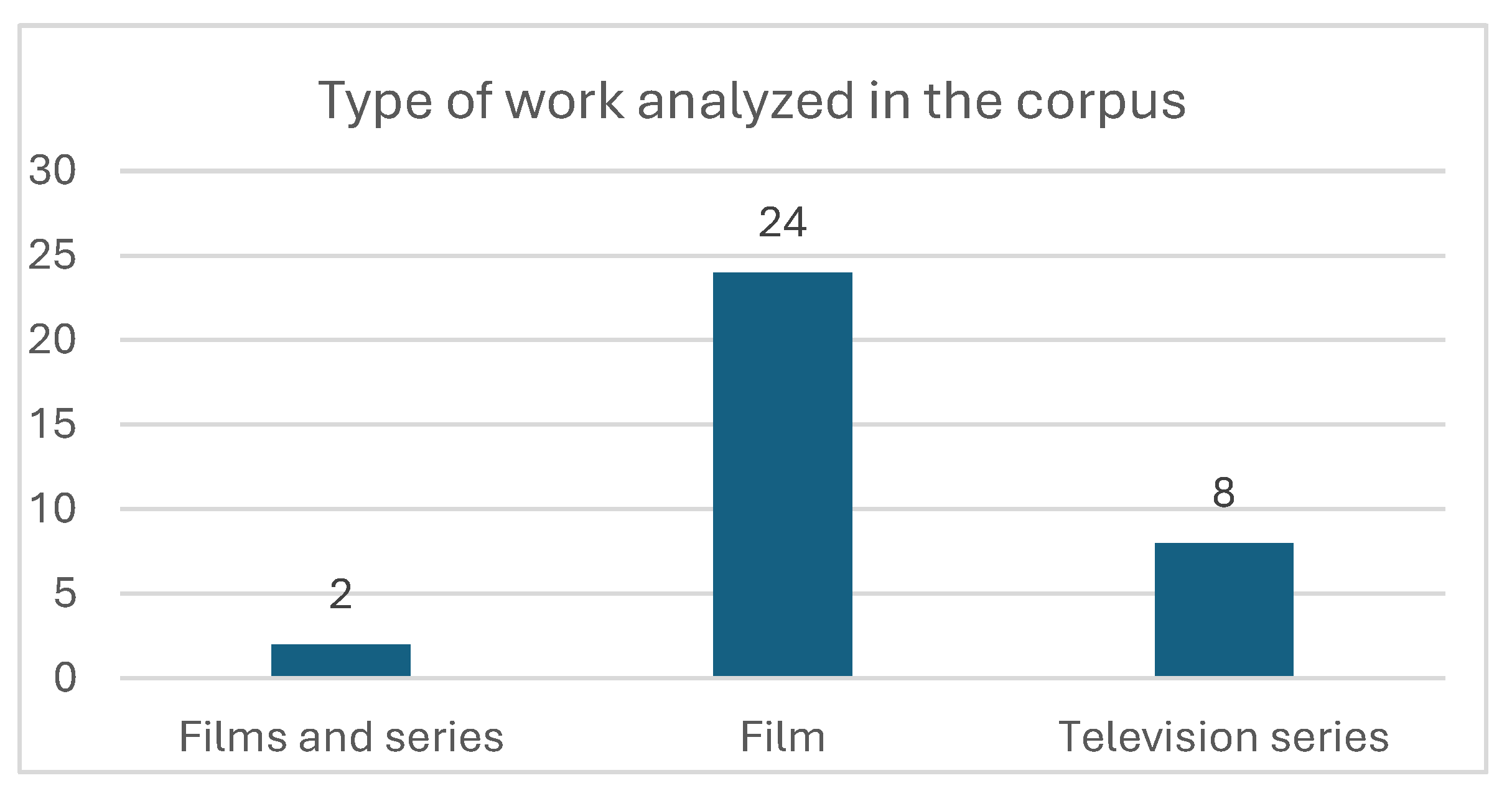

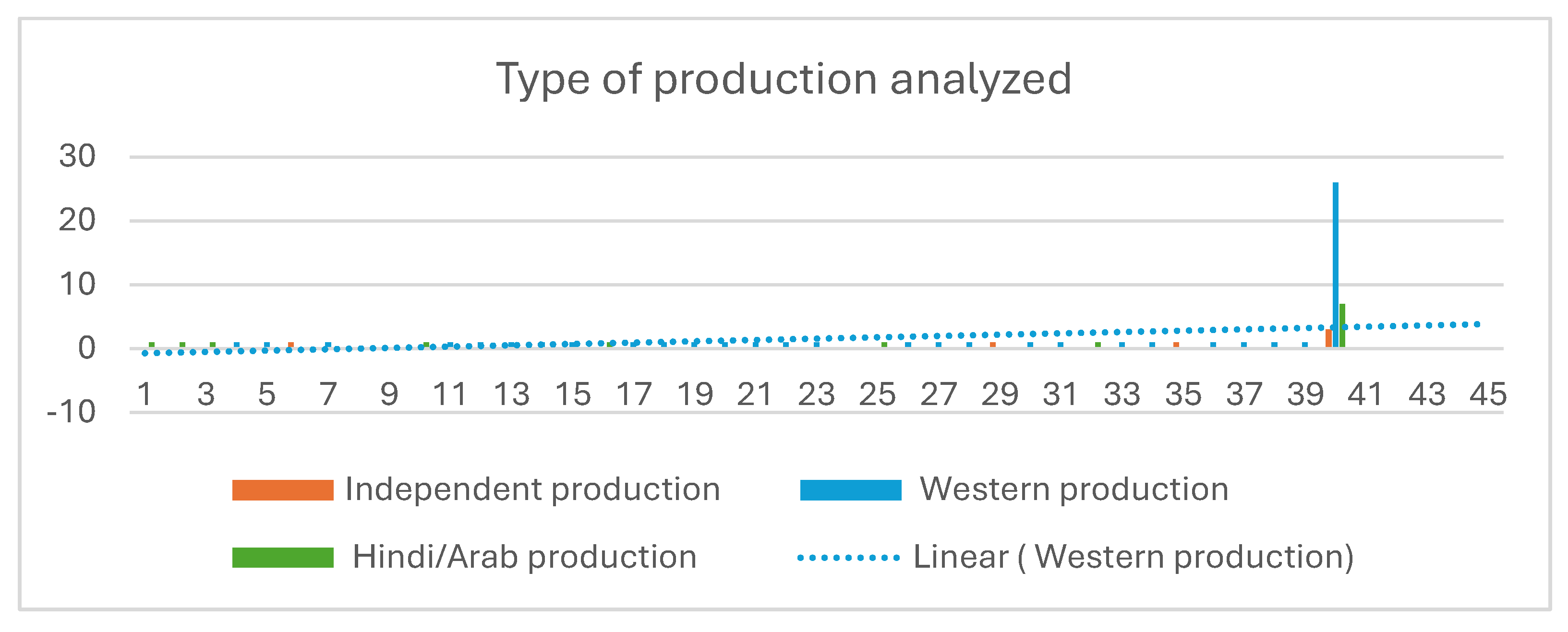

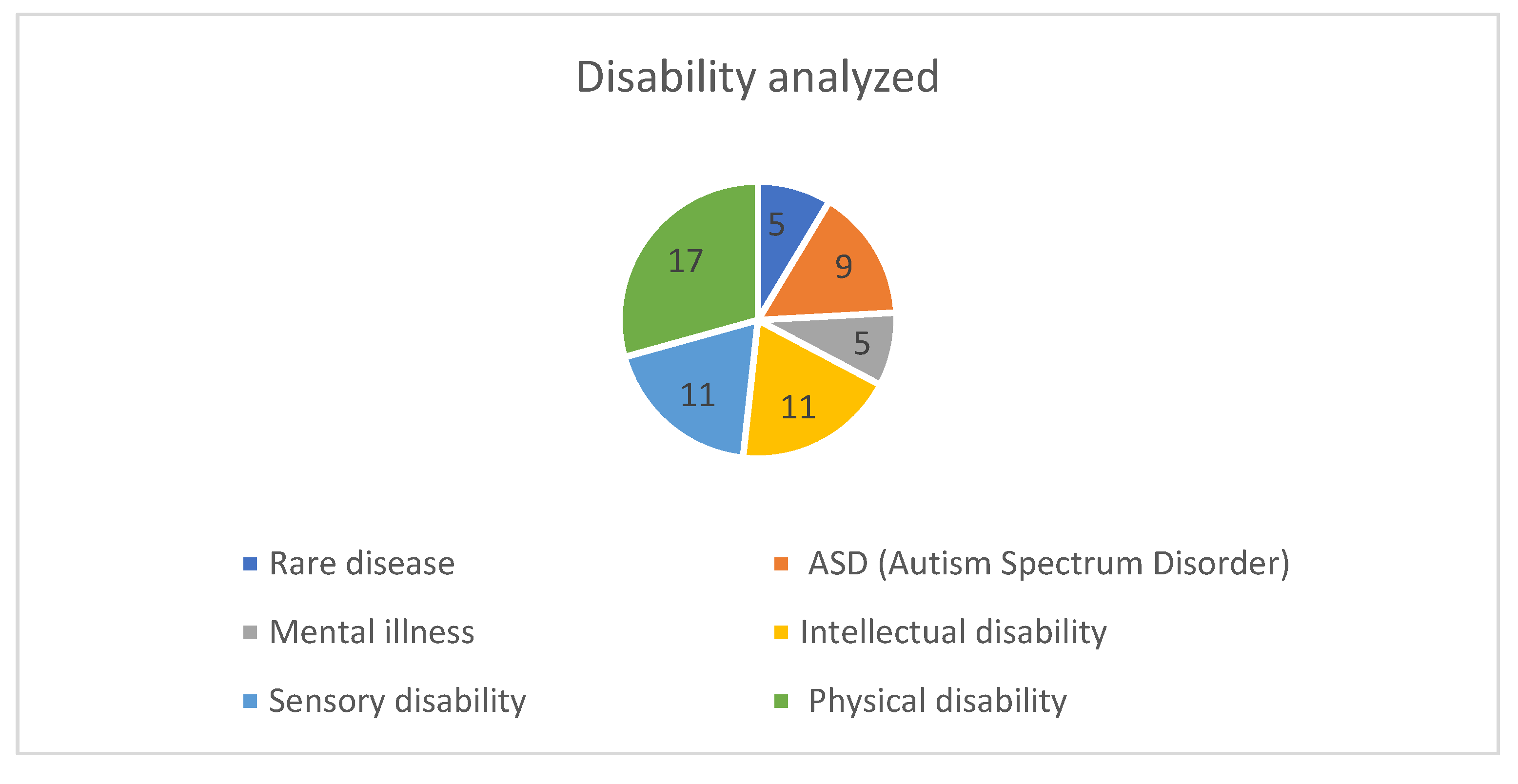

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

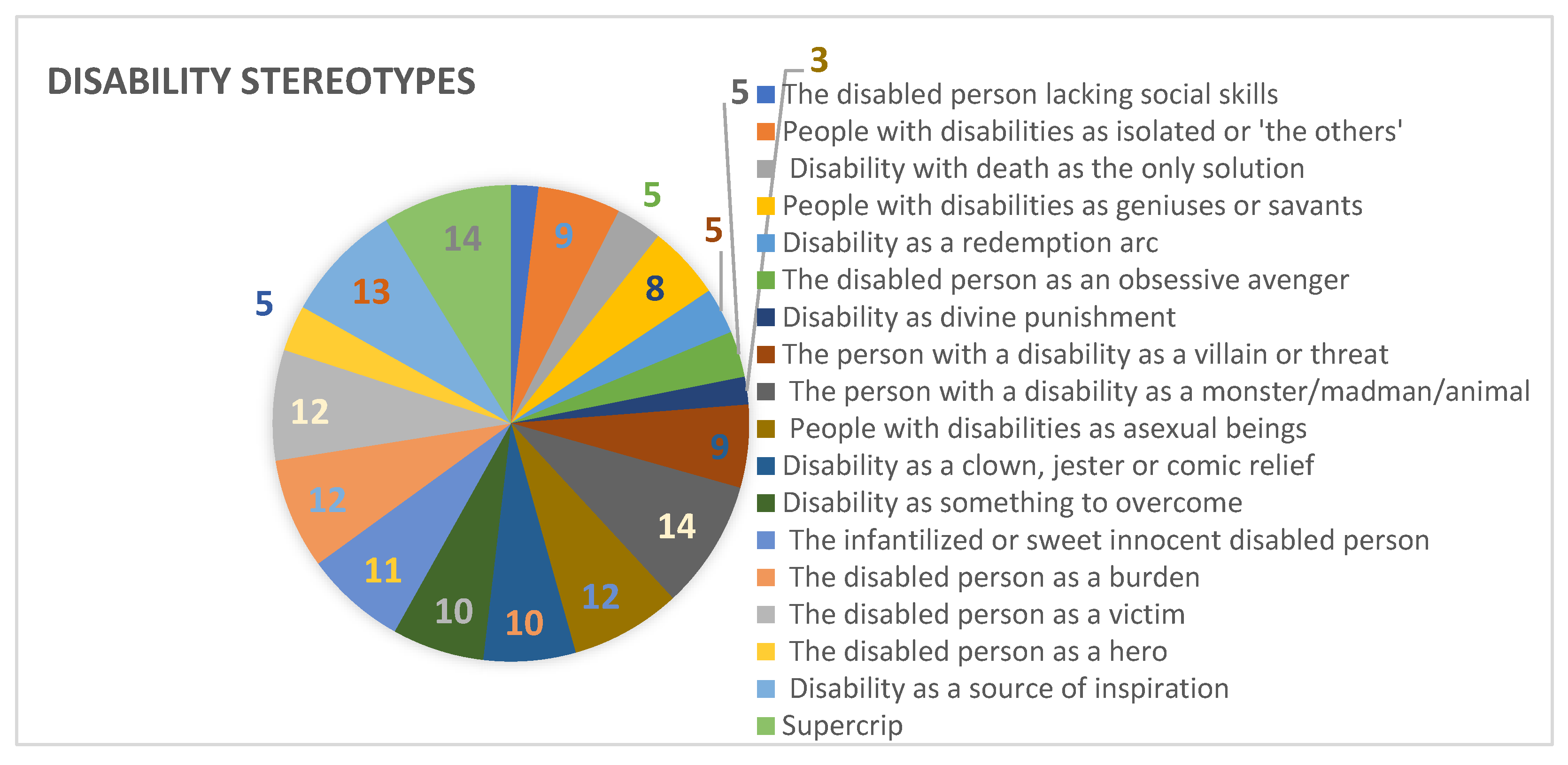

3.2. Stereotypes of Disability in Audiovisual Media

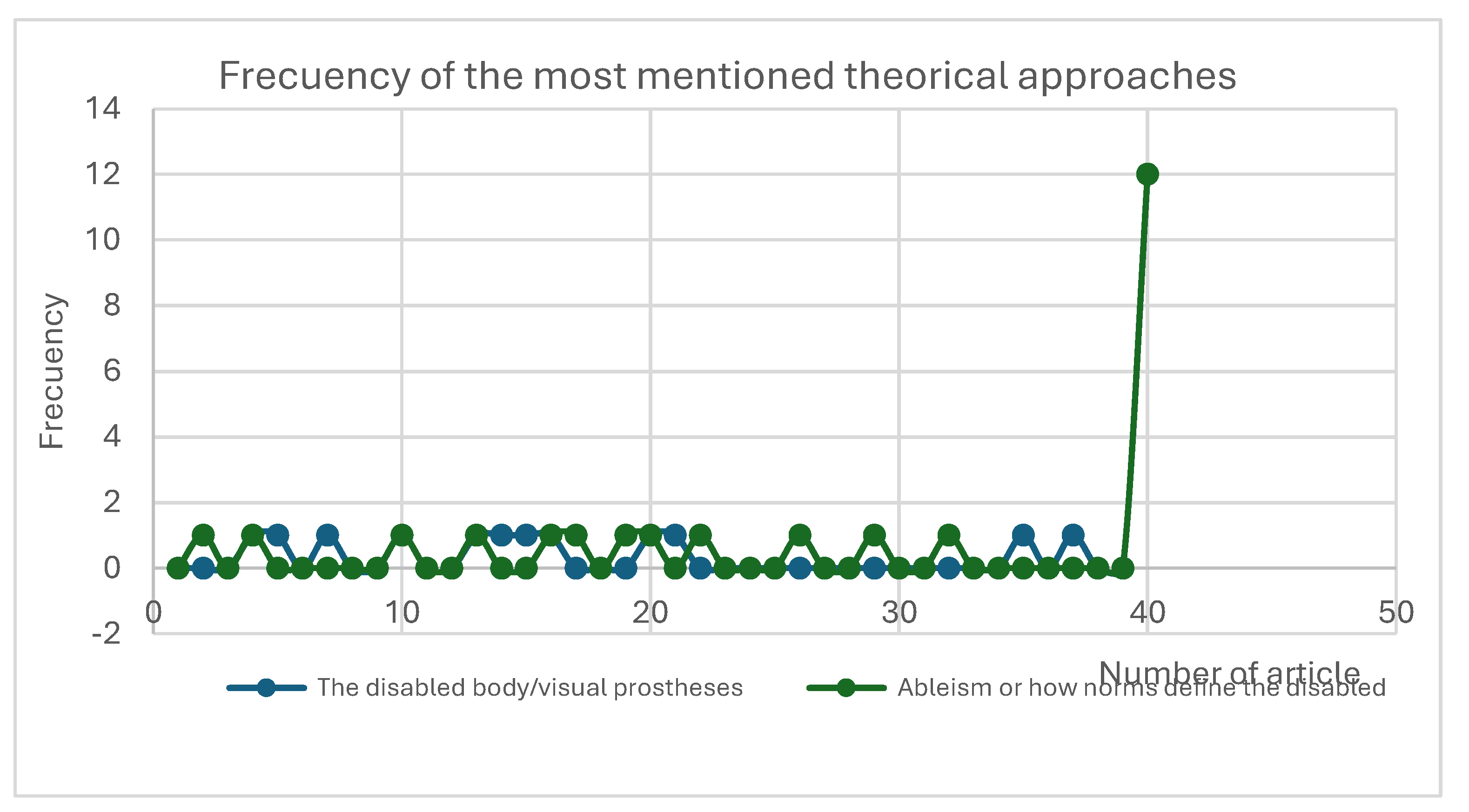

3.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Approaches

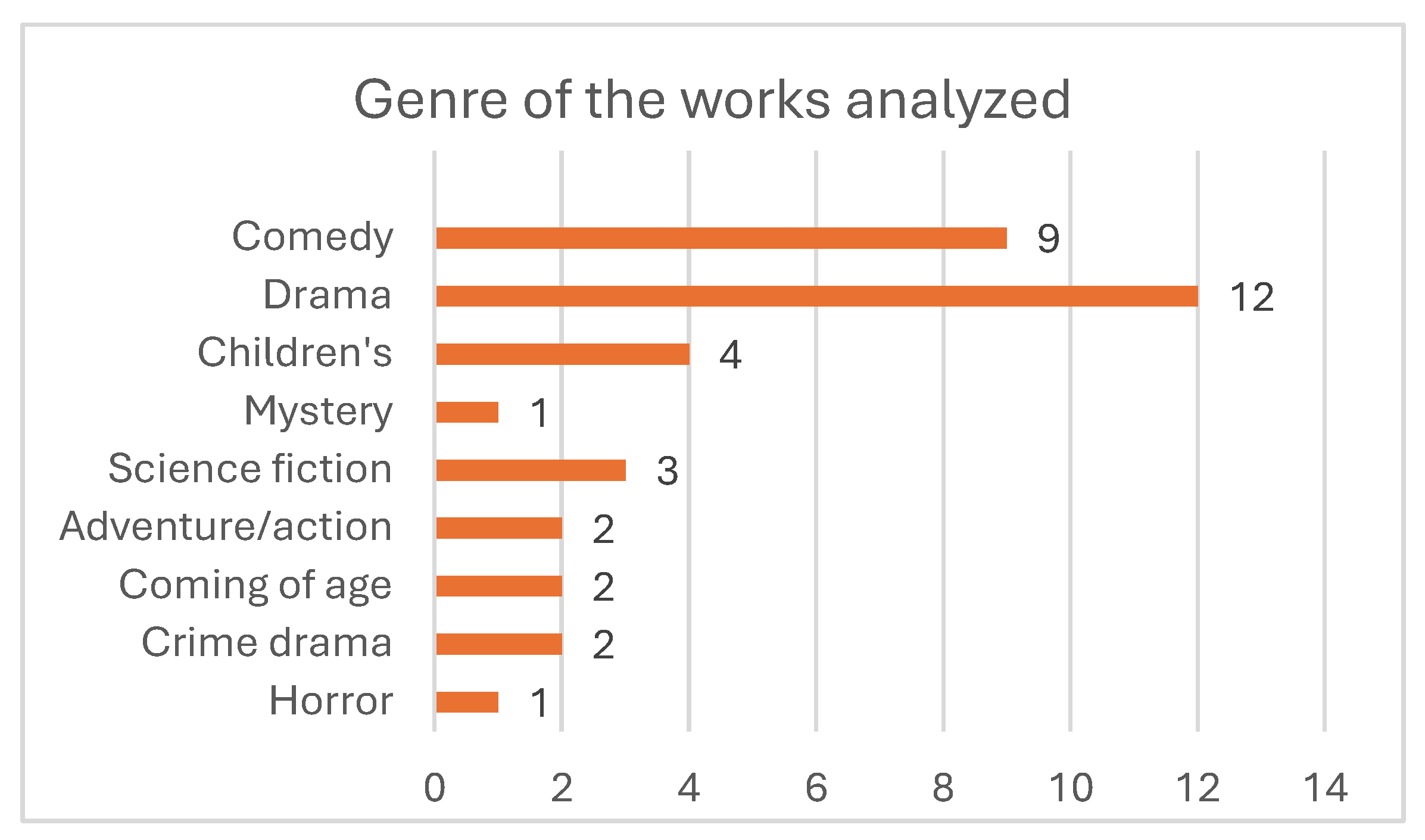

3.4. Genres, Themes, and Character Traits

3.5. Gaps and Limitations Highlighted by the Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Predominant Theoretical Approaches

4.3. Genres, Themes, and Character Representation

4.4. Identified Gaps and Future Research Directions

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Note

References

- Salar Sotillos, M.J. Cine, realidad social y educación. Docencia y Derecho 2021, 7, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furió Alarcón, A. Cinema, a Tool for Social Change. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024, 9, 01–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Amilburu, M.; De Santiago Ruiz, P.; Orte García, J.M. El Cine En 7 Películas. Guía Básica Del Lenguaje Cinematográfico; UNED: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-362-7234-5. [Google Scholar]

- Goyes Narváez, J.C. Audiovisualidad, Cultura Popular e Investigación-Creación. Cuad. Cent. Estud. Diseño Comun. 2020, 79, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo Moratalla, T. Figurarse La Vida. A Propósito de La Antropología Cinematográfica de Julián Marías. THÉMATA Rev. Filos. 2012, 46, 517–527. [Google Scholar]

- Osácar Marzal, E. La Imagen Turística de Barcelona a Través de Las Películas Internacionales. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramesco, C. Colores de Cine: La Historia Del Séptimo Arte En 50 Películas; Blume: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; ISBN 978-84-100-4819-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Couto, D. Imágenes Del Control Social. Miedo y Conmoción En El Espectador de Un Mundo Bajo Amenaza. Re-Visiones 2024, 5. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/REVI/article/view/94597.

- Aguilar Carrasco, P. El Papel de La Mujer En El Cine; Santillana Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-141-0839-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardinilo, A. La Transformación de Las Noticias: Walter Lippmann y La Opinión Pública. Rev. Estud. Socioeducativos RESED 2023, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Dalmeda, M.E.; Chhabra, G. Modelos teóricos de discapacidad: un seguimiento del desarrollo histórico del concepto de discapacidad en las últimas cinco décadas. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2019, 7, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gascón-Cuenca, A.; Bernabé Padilla, I.; Hernández Azcón, A.; Ramos Miralles, A.; Martínez Trigo, A.; Martínez Cameros, C.E.; Costa Navarro, D.; Jusue Moñino, N.G.; Muñoz Ruíz, R.; Fierrez Soria, S.; et al. El Ordenamiento Jurídico Español y Las Personas Con Discapacidad: Entre La Autodeterminación y El Paternalismo. Clínica Juríd. Justícia Soc. Inf. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud ICF : The International Classification of Functioning Disabilities and Health : Short Version; WHO, 2001; p. 228; ISBN 92-4-154544-5.

- Rodríguez Díaz, S.; Sánchez Padilla, R.; Ferreira, M.A.V. La Discapacidad Como Diversidad Funcional: Imágenes de Una Construcción Social. Intersticios Rev. Sociológica Pensam. Crít. 2024, 18, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Ramírez, G.E. El Capacitismo, Estructura Mental de Exclusión de Las Personas Con Discapacidad; CERMI, Ed.., Ediciones Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2023; ISBN 978-84-18433-67-2. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, J. Violencia, género y discapacidad: la ideología de la normalidad en el cine español. Hispanófila 2016, 177, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, J. Culture and Mood Disorders: The Effect of Abstraction in Image, Narrative and Film on Depression and Anxiety. Med. Humanit. 2020, 46, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ter Haar, A.; Hilberink, S.R.; Schippers, A. Lived Experiences of Public Disability Representations: A Scoping Review. Disabilities 2025, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cortes, O.D.; Betancourt Núñez, A.; Bernal Orozco, M.F.; Vizmanos- Lamotte, B. Scoping Reviews: Una Nueva Forma de Síntesis de La Evidencia. Investig. En Educ. Medica 2022, 11, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Borrego, M.; González-Cortés, M.E. Cultural Journalism and Disability in Cinema: A View of Its Historical Evolution through Specialized Critique. Vis. Rev. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. Vis. 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, C.W. Marketing the Prosthesis: Supercrip and Superhuman Narratives in Contemporary Cultural Representations. Philosophies 2020, 5 (3), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies5030011*.

- Maestre Limiñana, S. La Mirada Rehabilitante En Campeones y Mar Adentro. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2024, 12, 241–252. https://www.cedid.es/redis/index.php/redis/article/view/1032*.

- Martausová, M. Authenticity in Representations of down Syndrome in Contemporary Cinema: The “Supercrip” in the Peanut Butter Falcon (2019). Ekphrasis 2021, 25, 26–40. https://doi.org/10.24193/EKPHRASIS.25.3*.

- Shaji, S.; C, S. Challenging conventional heroism: redefining heroism through the representation of disabled superheroes in daredevil and x-men. ShodhKosh J. Vis. Perform. Arts 2023, 4 (2), 349-356. https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2.2023.452*.

- Gawande, V.; Kashyap, G. Discovering Impaired Superheroes in Hindi Movies: A Study of Characterization of Disabled in Movies and Its Impact on Their Social Life; Community & Communication Amity School of Communication; 2017, 5, 52-59. *.

- Solís García, P. La Visión de La Discapacidad En La Primera Etapa de Disney: Blancanieves y Los 7 Enanitos, Alicia En El País de Las Maravillas y Peter Pan. Rev. Med. Cine 2019, 15, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.14201/rmc20191527379*.

- Kramer, R. Crime Media as Cinematic “Freak Show”: Ableism and Speciesism in Retelling Dahmer. Crime Media Cult. 2024, 20, 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/17416590231218739*.

- Wischert-Zielke, M. The Impulse-Image of Vampiric Capital and the Politics of Vision and Disability: Evil and Horror in Don’t Breathe. Cinej Cine. J. 2021, 9, 492–525. https://doi.org/10.5195/cinej.2021.382*.

- Gauci, V.; Callus, A.M. Enabling Everything: Scale, Disability and the Film The Theory of Everything. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 1282–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1071942*.

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Narrative Representation of Depression, ASD, and ASPD in «Atypical», «My Mad Fat Diary» and «The End of The F***ing World». Commun. Soc. 2023, 36, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.36.1.17-34*.

- Planella Ribera, J.; Piquer, M.P.; Bartoll, Ó.C.; Escalada, M.C.M. The Vision of Disability through Cinema. The Campeones Film as a Case Study. Encuentros Maracaibo 2021, 13, 11–18.*.

- Santana Quintana, M. del P. Impossible Paradise: Sex and Functional Diversity in Oasis (Oasiseu, 2002). Anclajes 2019, 23, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.19137/anclajes-2019-2338*.

- Roshini, R.; Rajasekaran, V. An Analysis of Disability in The Little Mermaid: Examining Disparities and Similarities in the Fairytale and Its Movie Adaptation. Stud. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 220–226. https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v11i4.6128*.

- Clark, R.E. Azeem and the Witch: Race, Disability, and Medievalisms in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Open Libr. Humanit. 2023, 9, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.9796*.

- Mishra, S. Portrayal of Disability in Hindi Cinema. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i04.25030*.

- Zaptsi, A.; Vera Moreno, B.; Garrido, R. Análisis Psicosocial de La Representación Televisiva de La Diversidad Funcional Como Estrategia de Alfabetización Mediática. Ámbitos Rev. Int. Comun. 2024, 65, 32–52. https://doi.org/10.12795/ambitos.2024.i65.02*.

- Martos Contreras, E. The Treatment of Disability in El Cochecito (1960) | El tratamiento de la discapacidad en el cochecito (1960). Rev. Med. Cine 2024, 20, 257–268. https://doi.org/10.14201/rmc.31838*.

- Ressa, T. Histrionics of Autism in the Media and the Dangers of False Balance and False Identity on Neurotypical Viewers. J. Disabil. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1163/25888803-bja10009*.

- Aspler, J.; Harding, K.D.; Cascio, M.A. Representation Matters: Race, Gender, Class, and Intersectional Representations of Autistic and Disabled Characters on Television. Stud. Soc. Justice 2022, 16, 323–348. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v16i2.2702*.

- García León, D.L. Body and Disability in Recent Colombian Cinema. The Case of Porfirio (2019) by Alejandro Landes | Cuerpo y Discapacidad En El Cine Colombiano Reciente. El Caso de Porfirio (2019) de Alejandro Landes. Bull. Hisp. Stud. 2021, 98, 507–529. https://doi.org/10.3828/bhs.2021.29*.

- García León, D.L.; García León, J.E. Representing Male Disability in Colombian Audiovisual Media: The Masking of Social and Political Intersections inLos Informantes. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2022, 57, 867–886. https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2022.62*.

- Wang-Xu, S. The ambivalent vision: the “crip” invention of “blind vision” in blind massage. Int. J. Film Media Arts 2023, 8, 89–107. https://doi.org/10.24140/ijfma.v8.n2.06*.

- Biernoff, S. Sacha Polak’s Dirty God and the Politics of Authenticity. Cine. Cie 2022, 22, 21–36. https://doi.org/10.54103/2036-461X/17384*.

- Tharian, P.R.; Henderson, S.; Wathanasin, N.; Hayden, N.; Chester, V.; Tromans, S. Characters with autism spectrum disorder in fiction: Where are the women and girls? Advances in Autism 2019, 5(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0043*.

- Coronel-Hidalgo, J.; Cevallos-Solorzano, G.; Torres-Galarza, A.; Bailón-Moscoso, N. Down Syndrome Cinematography Analysis | Análisis de La Cinematografía Del Síndrome de Down. Educ. Medica 2023, 24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2023.100823*.

- Dean, M.; Nordahl-Hansen, A. A Review of Research Studying Film and Television Representations of ASD. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 9, 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00273-8*.

- Mendivelso Leal, R.; Hoyos Cuartas, L.A. Las Representaciones Sociales En La Discapacidad a Partir de La Cinematografía Infantil. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Salud UDES 2016, 3, 27.*.

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Communicating Health: Depictions of Depression, Antisocial Personality Disorder, and Autism without Intellectual Disability in British and U.S. Coming-of-Age TV Series. Humanities 2022, 11(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11030066*.

- Wohlmann, A.; Harrison, M. To Be Continued: Serial Narration, Chronic Disease, and Disability. Lit. Med. 2019, 37(1), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2019.0002*.

- Domaradzki, J. Treating Rare Diseases with the Cinema: Can Popular Movies Enhance Public Understanding of Rare Diseases? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02269-x*.

- Martínez, G.M.; Mangado, M. Stuttering in Cinema: Textual Analysis of the Paradigm Shift in Its Representation. Fonseca J. Commun. 2022, 24, 53–86. https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc.28288*.

- Deb, P. Nuances of the Unique and Evolving Conceptualisation of Intellectual Disability in India: A Study of the Changing Artistic Parlance of Representing Intellectually Disabled People in Mainstream Hindi Cinema. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2022, 50, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12467*.

- Carter-Long, L. Disability cinema’s next wave: observational agency subverts the ableist gaze. Film Q. 2022, 76, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1525/FQ.2022.76.2.55*.

- Sanz-Simón, L. The Construction of Characters with Disabilities in Film: The Importance of Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication. Vis. Rev. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. 2022, 11(4), 1- 16. https://doi.org/10.37467/revvisual.v9.3701*.

- Anand, R.; Gupta, K. From Representation to Re-Presentation: A Study of Disability in Literature and Cinema. Int. J. Innov. Multidiscip. Res. 2022, 5.*.

- Wilkins, C. Adaptation, Parody, and Disabled Masculinity in Motherless Brooklyn. Humanit. Switz. 2023, 12, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12040066*.

- Sharma, A. Representation of Disability-A Space of One’s Own in Literature and Cinema. Lapis Lazuli Int. Lit. J. 2022, 12.*.

- Alkayed, Z.S.; Kitishat, A.R. Language Teaching for Specific Purposes: A Case Study of the Degree of Accuracy in Describing the Character of Mental Disabilities in Modern Arabic Drama (Egyptian Film Toot-Toot as an Example). J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 12, 1039–1050. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1206.20*.

- Al-Zoubi, S.M.; Al-Zoubi, S.M. The Portrayal of Persons with Disabilities in Arabic Drama: A Literature Review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104221*.

| Database | Query | Results |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY(("disability" OR "disabled characters" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("stereotypes" OR "estereotipos") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "audiovisual media" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión")) | 53 |

| Web of Science (WOS) | TS=(("disability" OR "disabled characters" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("stereotypes" OR "estereotipos") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "audiovisual media" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión")) | 54 |

| ERIC | ("disability" OR "disabled characters" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("stereotypes" OR "estereotipos") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "audiovisual media" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión") | 24 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY(("disability" OR "representación de la discapacidad" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("representation" OR "depiction" OR "imagen" OR "portrayal") AND ("theory" OR "theoretical framework" OR "conceptual approach" OR "marco teórico" OR "enfoque conceptual" OR "perspective") AND ("film" OR "movie" OR "cinema" OR "television" OR "TV series" OR "media" OR "audiovisual" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión" OR "medios audiovisuales")) | 247 |

| Web of Science (WOS) | TS=(("disability" OR "representación de la discapacidad" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("representation" OR "depiction" OR "imagen" OR "portrayal") AND ("theory" OR "theoretical framework" OR "conceptual approach" OR "marco teórico" OR "enfoque conceptual" OR "perspective") AND ("film" OR "movie" OR "cinema" OR "television" OR "TV series" OR "media" OR "audiovisual" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión" OR "medios audiovisuales")) | 155 |

| ERIC | ("disability" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("representation" OR "media portrayal" OR "imagen" OR "representación") AND ("theory" OR "conceptual approach" OR "marco teórico" OR "enfoque conceptual" OR "perspective") AND ("film" OR "TV series" OR "media" OR "audiovisual" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión") | 25 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY (("disability" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("character traits" OR "rasgos de personajes" OR "genre" OR "género audiovisual" OR "themes" OR "temáticas") | 121 |

| Web of Science (WOS) | TS=(("disability" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("character traits" OR "rasgos de personajes" OR "genre" OR "género audiovisual" OR "themes" OR "temáticas") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión")) | 92 |

| ERIC | ("disability" OR "personas con discapacidad") AND ("character traits" OR "rasgos de personajes" OR "genre" OR "género audiovisual" OR "themes" OR "temáticas") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión" OR "audiovisual media") | 32 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY (("disability representation" OR "representación de la discapacidad" OR ("disability" AND "media")) AND ("review" OR "discussion" OR "limitations" OR "future research" OR "research agenda" OR "estado del arte") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "audiovisual media" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión")) | 57 |

| Web of Science (WOS) | TS=(("disability representation" OR "representación de la discapacidad" OR ("disability" AND "media")) AND ("review" OR "discussion" OR "limitations" OR "future research" OR "research agenda" OR "estado del arte") AND ("film" OR "movies" OR "TV series" OR "audiovisual media" OR "cine" OR "series de televisión")) | 68 |

| ERIC | ("disability" OR "discapacidad") AND ("media" OR "film" OR "cine" OR "audiovisual" OR "TV series" OR "series de televisión") | 32 |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Peer-reviewed journal articles, doctoral theses, or research reports with a clear methodology. | Studies that do not analyze representations of disability in audiovisual media. |

| Qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method studies analyzing disability representations in audiovisual productions. | Complete books |

| Studies examining characters with disabilities in films, television series, telenovelas, or miniseries. | Studies focusing on formats such as documentaries, talk shows, reality shows, news, institutional campaigns, social media, video games, or literature. |

| Studies addressing stereotypes, visual discourses, theoretical models such as ableism or disability models, or character traits related to disability. | Publications lacking empirical basis or an explicit methodology (e.g., essays, editorials, or opinion reviews without systematic analysis). |

| Studies published from the year 2015 onward. | Studies published before 2015. |

| Studies written in English or Spanish. | Duplicated, incomplete studies, or those without full-text access. |

| Number and title of the article | Authorship | Country | Year | Journal | SJR, quartille | Media | Disability represented |

| 1.Language Teaching for Specific Purposes: A Case Study of the Degree of Accuracy in Describing the Character of Mental Disabilities in Modern Arabic Drama (Egyptian Film Toot-Toot as an Example) | Alkayed, Z. S., & Kitishat, A. R. | United Kingdom | 2021 | Journal of Language Teaching and Research | 0.282 (Q1) | Film | Intellectual disability |

| 2.From representation to re-presentation: A study of disability in cinematic and literary text | Anand, R. & Gupta, K. | India | 2022 | International Journal of Innovation and Multidisciplinary Research | Not available | Films | Multiple |

| 3.The portrayal of persons with disabilities in Arabic drama: A literature review | Al-Zoubi,S. M. & Al-Zoubi, S. M. | United Estates | 2022 | Research in Developmental Disabilities | 0.900 (Q2) | Films and Series | Multiple |

| 4.Representation Matters: Race, Gender, Class, and Intersectional Representations of Autistic and Disabled Characters on Television | Aspler, J., Harding, K. & Cascio, M. | Canada | 2022 | Studies in Social Justice | 0.284 (Q2) | Series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) |

| 5.Sacha Polak’s Dirty God and the Politics of Authenticity | Biernoff, S. | Italy | 2022 | Cinema et Cie | 0.103 (Q3) | Film | Physical deformity after an acid attack |

| 6.Disability cinema´s next wave: observational agency subverts the ableist gaze | Carter-Long, L. | United States | 2022 | Film Quarterly | 0.342 (Q1) | Films | Physical disability |

| 7.Azeem and the Witch: Race, Disability, and Medievalisms in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves | Clark, R.E. | United Kingdom | 2023 | Open Library of Humanities | 0.225 (Q2) | Film | Physical deformity (physical disability) |

| 8.Análisis de la cinematografía del síndrome de Down | Coronel- Hidalgo, J., Cevallos-Solorzano, G., Torres-Galarza, A. & Bailón- Moscoso, N. | Spain | 2023 | Educación Médica | 0.218 (Q3) | Película | Down's syndrome (a rare disease in our coding system). |

| 9.A Review of Research Studying Film and Television Representations of ASD | Dean, M. & Nordahl- Hansen, A. | United States | 2022 | Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 1.150 (Q1) | Films and Series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) |

| 10.Nuances of the unique and evolving conceptualisation of intellectual disability in India: A study of the changing artistic parlance of representing intellectually disabled people in mainstream Hindi cinema | Deb, P. | United Kingdom | 2022 | British Journal of Learning Disabilities- Special Isue | 0.437 (Q2) | Films | Intellectual disability |

| 11.Treating rare diseases with the cinema: Can popular movies enhance public understanding of rare diseases? | Domaradzki, J. | United Kingdom | 2022 | Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases | 1.269 (Q1) | Films | Rare diseases |

| 12.Marketing the Prosthesis: Supercrip and Superhuman Narratives in Contemporary Cultural Representations | Fahn, C. W. | Switzerland | 2020 | Philosophies | 0.286 (Q2) | Films | Physical disability |

| 13.Cuerpo y discapacidad en el cine colombiano reciente. El caso de Porfirio (2019) de Alejandro Landes | García- León, L.D. | United Kingdom | 2021 | Bulletin of Hispanic Studies | 0.121 (Q2) | Film | Physical disability |

| 14.Representing male disability in colombian audiovisual media: The masking of social and political intersections in los informantes | García-León, L. D. & García-León, J.E. | United States | 2022 | Latin American Research Review | 0.442 (Q1) | Series | Physical disability and intellectual disability |

| 15.Enabling everything: scale, disability and the film The Theory of Everything | Gaucci, V. | United Kingdom | 2015 | Disability & Society | 0.951 (Q1) | Film | Physical disability |

| 16.Discovering impaired superheroes in Hindi movies: A study of characterization of disabled in movies and its impact on their social life | Gawande, V. & Kashyap, G. | India | 2017 | Journal of content, community & communication | 0.309 (Q2) | Film | Physical disability |

| 17.Crime media as cinematic “freak show”: Ableism and speciesism in retelling Dahmer | Kramer, R. | United Kingdom | 2023 | Crime, Media, Culture | 0.754 (Q1) | Series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) and intellectual disability |

| 18.Communicating Health: Depictions of Depression, Antisocial Personality Disorder, and Autism without Intellectual Disability in British and U.S. Coming-of-Age TV Series | Lopera- Mármol, M., Jiménez-Morales, M. & Jiménez- Morales, M. | Switzerland | 2022 | Hummanities | 0.155 (Q3) | Series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder)Depression, Antisocial Personality Disorder (mental illness in our coding) |

| 19.Narrative representation of depression, ASD, and ASPD in “Atypical”, “My Mad Fat Diary” and “The End of The F**ing World” * | Lopera- Mármol, M., Jiménez-Morales, M. & Jiménez- Morales, M. | Spain | 2023 | Communicatiion and Society | 0.455 (Q1) | Series | ASD (Autistic Spectrum Disorder)Depression, Antisocial Personality Disorder (mental illness in our coding) |

| 20.La mirada rehabilitante en Campeones y Mar adentro: representación de la discapacidad desde la no discapacidad | Maestre Limiñana, S. | Spain | 2024 | Revista Española de Discapacidad | Not available | Films | Physical disability and intellectual disability |

| 21.Authenticity in representations of down syndrome in contemporary cinema: The “supercrip” in the Peanut Butter Falcon (2019) | Martausová, M. | Romania | 2021 | Ekphrasis | 0.105 (Q3) | Film | Down's syndrome (a rare disease in our coding system). |

| 22.El tratamiento de la discapacidad en El cochecito (1960) | Martos Contreras, E. | Spain | 2024 | Revista de Medicina y Cine | 0.189 (Q1) | Film | Physical disability |

| 23.La tartamudez en el cine: Análisis textual del cambio de paradigma en su representación | Mejías Martínez, G. & Mangado Martínez, M. | Spain | 2022 | Fonseca, Journal of Communication | 0.239 (Q2) | Film | Stuttering (Sensory disabilitylity in our coding) |

| 24.Las representaciones sociales en la discapacidad a partir de la cinematografía infantil | Mendivelso, R & Hoyos- Cuartas, L. A. | Colombia | 2016 | Revista Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud UDES | Not available | Films | Multiple |

| 25.Portrayal of Disability in Hindi Cinema | Mishra, S. | India | 2024 | International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research | Not available | Films | Multiple |

| 26.La visión de la discapacidad a través del cine. La película “Campeones” como estudio de caso | Planella-Ribera, J., Pallarès-Piquer, M., Chiva-Bartoll, O., & Muñoz-Escalada, M. C. | Spain | 2021 | Encuentros. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, Teoría Social y Pensamiento Crítico | 0.163 (Q2) | Film | Intellectual disability |

| 27.Histrionics of Autism in the Media and the Dangers of False Balance and False Identity on Neurotypical Viewers | Ressa, T. | Netherlands | 2021 | Journal of Disability Studies in Education | 0.475 (Q2) | Series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) |

| 28.An Analysis of Disability in The Little Mermaid: Examining Disparities and Similarities in the Fairytale and Its Movie Adaptation | R. Roshini, R. & Rajasekaran, V. | United States | 2023 | Studies in Media and Communication | 0.221 (Q3) | Film | Physical disability |

| 29.Impossible Paradise: Sex and Functional Diversity in Oasis (Oasiseu, 2002) | Santana- Quintana, M.P. | Argentina | 2019 | Anclajes | 0.147 (Q2) | Film | Physical disability |

| 30.The construction of characters with disabilities in film: The importance of verbal and non-verbal communication | Sanz-Simón, L. | Spain | 2022 | Visual Review. International Visual Culture Review/Revista Internacional de Cultura | 0.166 | Films | Multiple |

| 31.Challenging conventional heroism: Redefining heroism through the representation of disabled superheroes in Daredevil and X-men | Shaji, S. & C. S. | India | 2023 | ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts | Not available | Films | Physical disability and sensory disability |

| 32.Representation of Disability- A Space of One's Own in Literature and Cinema | Sharma, A | India | 2022 | Lapis Lazuli: An International Literary Journal | Not available | Films | Sensory disability |

| 33.La visión de la discapacidad en la primera etapa de Disney: Blancanieves y los 7 enanitos, Alicia en el País de las Maravillas y Peter Pan | Solís- García, P. | Spain | 2019 | Revista de Medicina y Cine | 0.189 (Q1) | Films | Multiple |

| 34.Characters with autism spectrum disorder in fiction: where are the women and girls? | Tharian, P.R;Henderson, S., Wathanasin, N.,Hayden, N.,Chester, V. & Tromans, S. | United Kingdom | 2019 | Advances in autism | 0.530 (Q3) | Film and series | ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) |

| 35.The ambivalent vision: the “crip” invention of “blind vision” in blind massage | Wang-Xu, S. | Portugal | 2023 | International Journal of Film and Media Arts | 0.127 (Q2) | Film | Sensory disability |

| 36.Adaptation, Parody, and Disabled Masculinity in Motherless Brooklyn | Wilkins, C. | Switzerland | 2023 | Hummanities | 0.155 (Q3) | Film | Intellectual disability |

| 37.The Impulse-Image of Vampiric Capital and the Politics of Vision and Disability: Evil and Horror in Don’t Breathe | Wischert-Zielke, M. | United States | 2021 | Cinej Cinema Journal | 0.197 (Q2) | Film | Sensory disability |

| 38.To be continued: Serial narration, chronic disease, and disability | Wohlmann, A. y Harrison, M. | United States | 2019 | Literature and Medicine | 0.132 (Q2) | Series | Parkinson's (Physical disability in our codification) |

| 39.Análisis psicosocial de la representación televisiva de la diversidad funcional como estrategia de alfabetización mediática | A. Zaptsi, A., Moreno- Vera, B. & Garrido, R. | Spain | 2024 | Ámbitos | 0,109 (Q4) | Series | Multiple |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).