Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

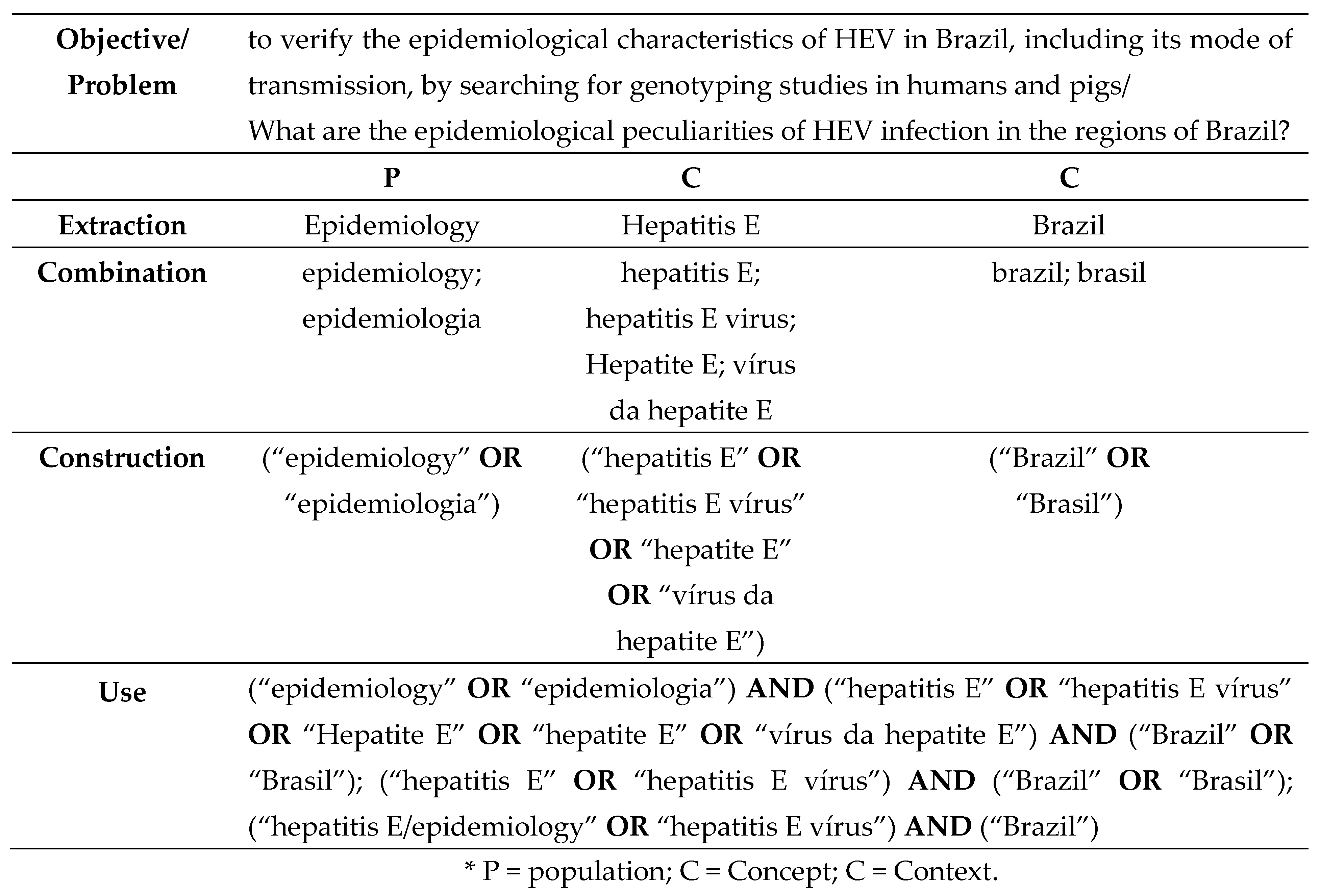

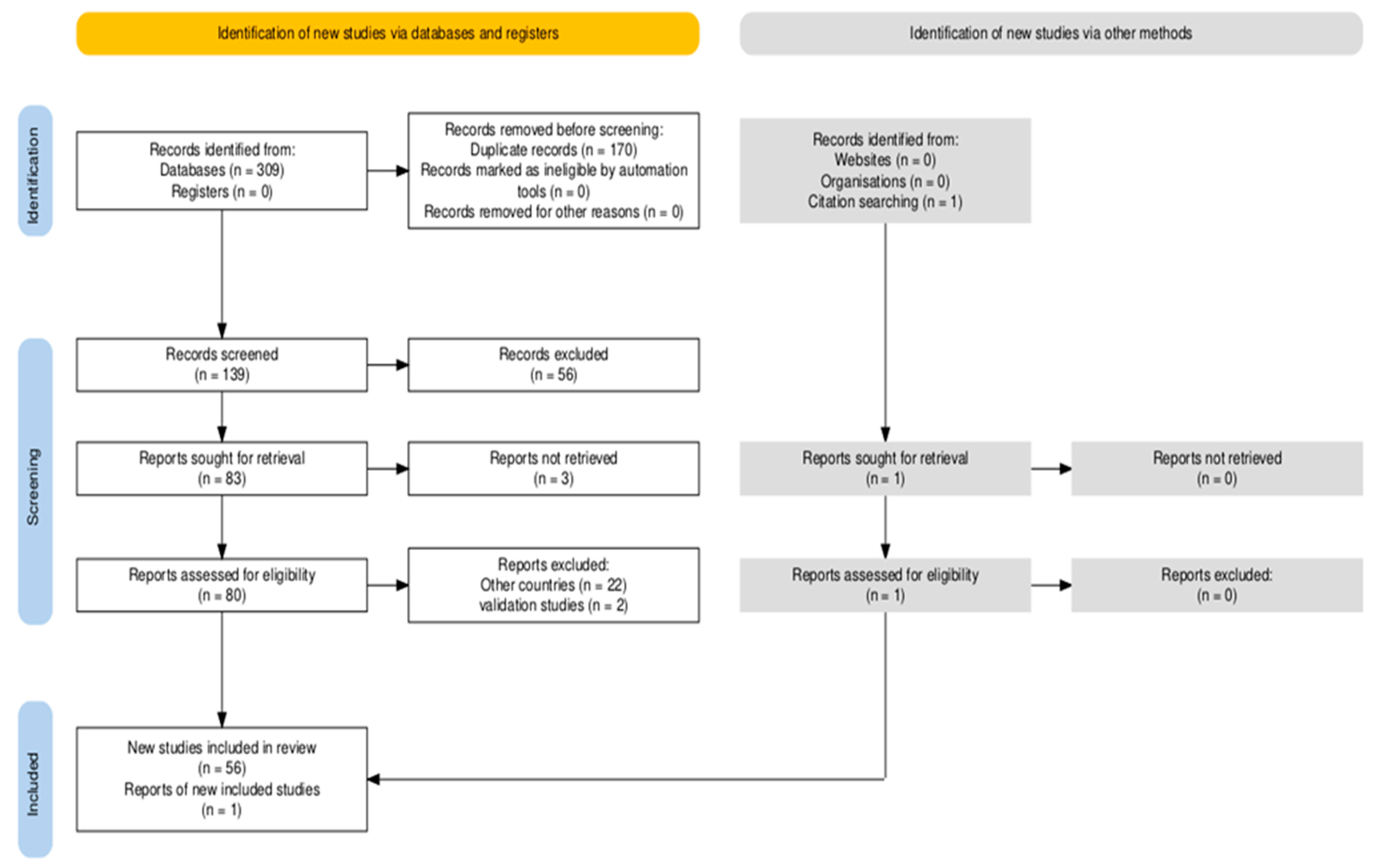

2. Materials and Methods

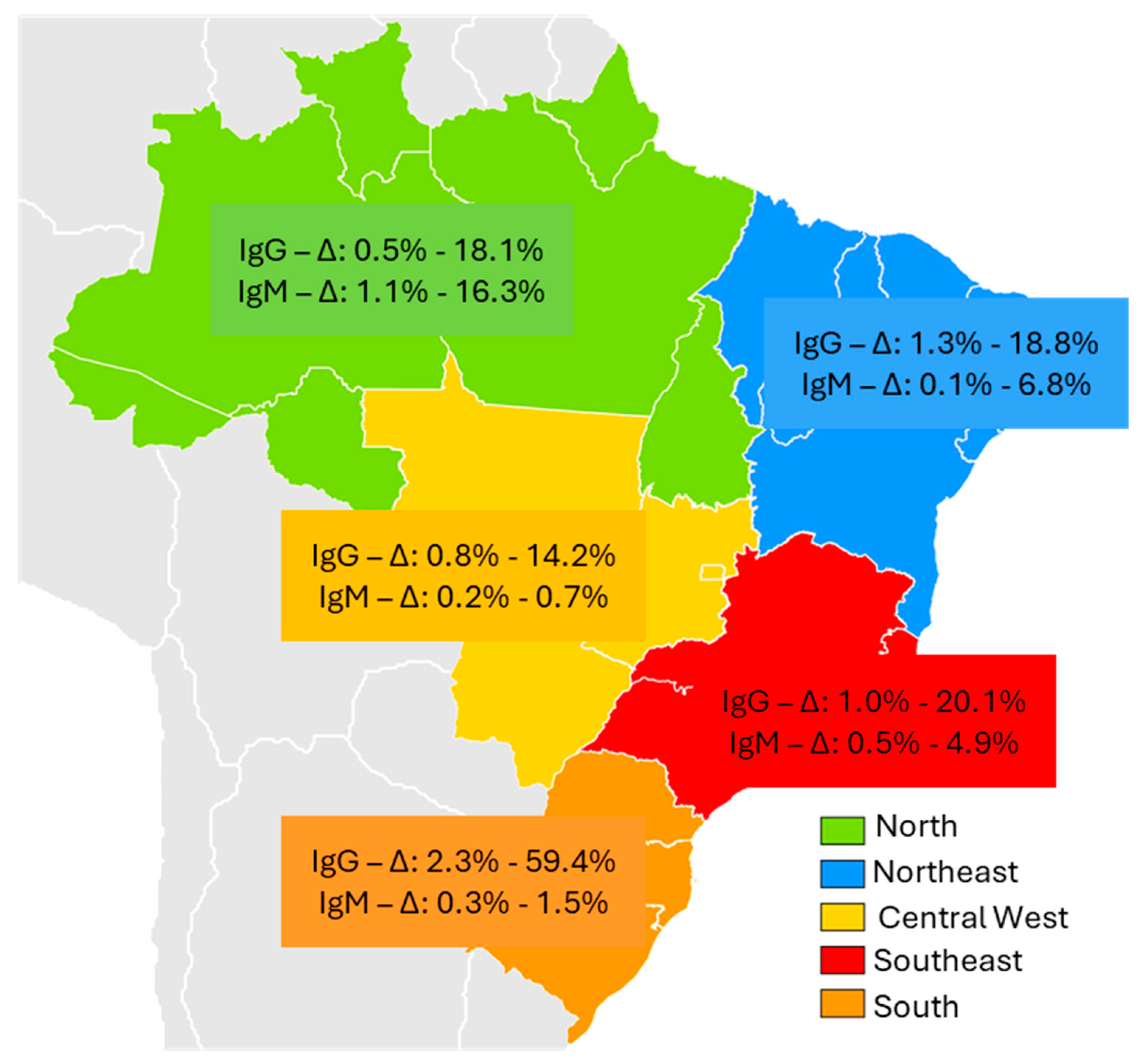

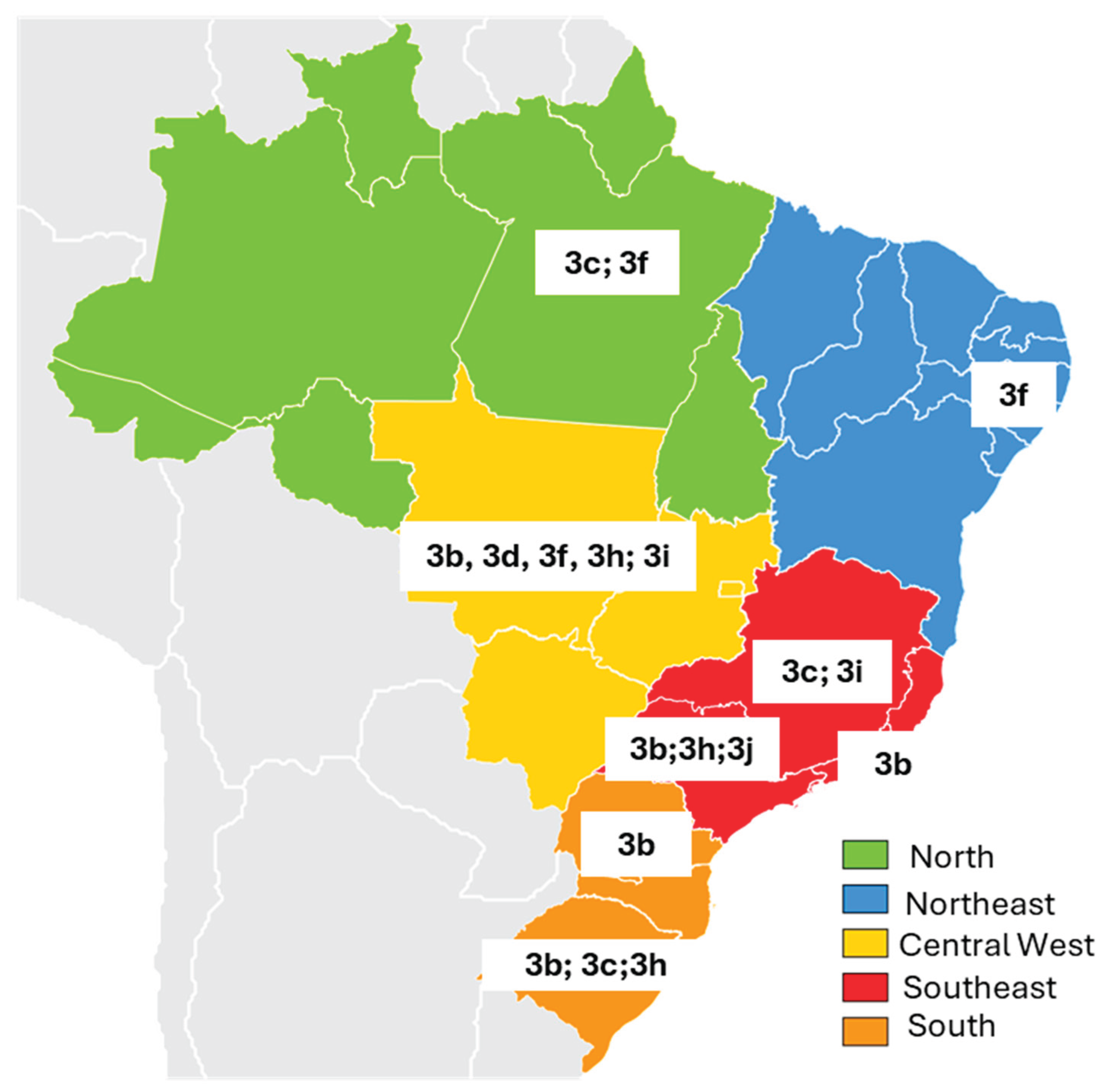

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HEV | Hepatitis E virus |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PCC | Population, Concept, and Context |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Debing, Y.; Moradpour, D.; Neyts, J.; Gouttenoire, J. Update on hepatitis E virology: Implications for clinical practice. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis E. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-e (accessed on 12 may 2025).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Acute hepatitis E—Level 4 cause. 2021. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-acute-hepatitis-e-level-4-disease (accessed on 12 may 2025).

- Purdy, M. A.; Drexler, J. F.; Meng, X. J.; Norder, H.; Okamoto, H.; Van der Poel, W. H. M.; Reuter, G.; de Souza, W. M.; Ulrich, R. G.; Smith, D. B. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Hepeviridae. The Journal of general virology 2022, 103, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E virus: host tropism and zoonotic infection. Curr Opin Microbiol 2021, 59, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamar, N.; Bendall, R.; Legrand-Abravanel, F.; Xia, N. S.; Ijaz, S.; Izopet, J.; Dalton, H. R. Hepatitis E. Lancet 2012, 379, 2477–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abravanel, F.; Lhomme, S.; El Costa, H.; Schvartz, B.; Peron, J. M.; Kamar, N.; Izopet, J. Rabbit Hepatitis E Virus Infections in Humans, France. Emerging infectious diseases 2017, 23, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T. P.; Pallerla, S. R.; Johne, R.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, E.; Schemmerer, M.; Wenzel, J. J.; Hofmann, J.; Shih, J. W. K.; Wedemeyer, H.; Bock, C. T. Hepatitis E: An update on One Health and clinical medicine. Liver international 2021, 41, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D. F. D. S. D.; Mesquita, J. R.; Dutra, V.; Nascimento, M. S. J. Systematic Review of Hepatitis E Virus in Brazil: A One-Health Approach of the Human-Animal-Environment Triad. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.; Dalton, H. R.; Abravanel, F.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis E virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014, 27, 116–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, C.; Knauf-Witzens, T.; Vahlenkamp, T.; Ulrich, R.G.; Johne, R. Hepatitis E virus and related viruses in wild, domestic and zoo animals: A review. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Ma, Z.; Bramer, W. M.; Cao, W.; de Man, R. A.; Peppelenbosch, M. P.; Pan, Q. The global epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver international 2020, 40, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, M. C.; Manchiero, C.; Dantas, B. P.; Bernardo, W. M.; Abdala, E.; Tengan, F. M. Prevalence of hepatitis E in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public health 2025, 244, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, A.M.; Heringer, T.P.; Medina-Pestana, J.O.; Ferraz, M.L.; Granato, C.F. First report and molecular characterization of hepatitis E virus infection in renal transplant recipients in Brazil. J Med Virol 2013, 85, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parana, R. , Cotrim, H. P.; Cortey-Boennec, M.L.; Trepo, C.; Lyra, L. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus IgG antibodies in patients from a referral unit of liver diseases in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1997, 57, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- de la Caridad Montalvo Villalba, M.; Owot, J. C.; Benedito, E. C.; Corredor, M. B.; Flaquet, P. P.; Frometa, S. S.; Wong, M. S.; Rodríguez Lay, L. deL. Hepatitis E virus genotype 3 in humans and swine, Cuba. Infection, genetics and evolution 2013, 14, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesslich, D.; Rocha júnior, J.E.; Crispim, M.A. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies among different groups in the Amazonian basin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2002, 96, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos-Castilho, A.M.; de Sena, A.; Geraldo, A.; Spada, C.; Granato, C.F. High prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies among blood donors in Southern Brazil. J Med Virol 2016, 88, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengan, F. M.; Figueiredo, G. M.; Nunes, A. K. S.; Manchiero, C.; Dantas, B. P.; Magri, M. C.; Prata, T. V. G.; Nascimento, M.; Mazza, C. C.; Abdala, E.; Barone, A. A.; Bernardo, W. M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E in adults in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infectious diseases of poverty 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songtanin, B.; Molehin, A. J.; Brittan, K.; Manatsathit, W.; Nugent, K. Hepatitis E Virus Infections: Epidemiology, Genetic Diversity, and Clinical Considerations. Viruses 2023, 15, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A. C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI evidence synthesis 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E. A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; … Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of internal medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R.; Page, M. J.; Pritchard, C. C.; McGuinness, L. A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18, e1230.

- Vitral, C.L.; da Silva-Nunes, M.; Pinto, M.A.; et al. Hepatitis A and E seroprevalence and associated risk factors: a community-based cross-sectional survey in rural Amazonia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.P.A.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Sánchez-Arcila, J.C.; et al. Seroprevalence of the Hepatitis E Virus in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Communities from the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.J.S.; Oliveira, C.M.A.; Sarmento, V.P.; et al. Hepatitis E virus infection among rural Afro-descendant communities from the eastern Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2018, 51, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.J.S.; Malheiros, A.P.; Sarmento, V.P.; et al. Serological and molecular retrospective analysis of hepatitis E suspected cases from the Eastern Brazilian Amazon 1993–2014. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, R.S.; Baia, K.L.N.; de Souza, S.B.; et al. Hepatitis E Virus in People Who Use Crack-Cocaine: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Remote Region of Northern Brazil. Viruses 2021, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraná, R.; Vitvitski, L.; Andrade, Z.; et al. Acute sporadic non-A, non-B hepatitis in Northeastern Brazil: etiology and natural history. Hepatology 1999, 30, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra, A.C.; Pinho, J.R.; Silva, L.K.; et al. HEV, TTV and GBV-C/HGV markers in patients with acute viral hepatitis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos-Castilho, A.M.; de Sena, A.; Domingues, A.L.; et al. Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence among schistosomiasis patients in Northeastern Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, L.A.; de Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Silva, J.V.J. Júnior; et al. Risk analysis and seroprevalence of HEV in people living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2019, 189, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, G.G.; Bezerra, L.A.; Silva Júnior, J.V.J.; Gonçales, J.P.; Montreuil, A.C.B.; Côelho, M.R.C.D. Analysis of seroprevalence and risk factors for hepatitis E virus (HEV) in donation candidates and blood donors in Northeast Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.R.M.G.; Batista, A.D.; Côelho, M.R.C.D.; et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus in patients with chronic liver disease. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.T.O.; Mariz, C.A.; Batista, A.D.; et al. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus Among Schistosomiasis mansoni Patients Residing in Endemic Zone in Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Sampaio, J.P.; Sinimbu, R.B.; Marques, J.T.; Neto, A.F.O.; Villar, L.M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus infection in blood donors from Piauí State, Northeast Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 29, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.M.; Freitas, N.R.; Kozlowski, A.; et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E antibodies in a population of recyclable waste pickers in Brazil. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 59, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.R.; Santana, E.B.; Silva, Á.M.; et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in patients with acute non-A, non-B, non-C hepatitis in Central Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.R.; Teles, S.A.; Caetano, K.A.A.; et al. Hepatitis E seroprevalence and associated factors in rural settlers in Central Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2017, 50, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.N.S.; Freitas, N.R.; Teles, S.A.; et al. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus RNA and antibodies in a cohort of kidney transplant recipients in Central Brazil. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, S. A.; Caetano, K. A. A.; Carneiro, M. A. D. S.; Villar, L. M.; Stacciarini, J. M.; Martins, R. M. B. Hepatitis E Prevalence in Vulnerable Populations in Goiânia, Central Brazil. Viruses 2023, 15, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, S.B.; Souto, F.J.; Fontes, C.J.; Gaspar, A.M. Prevalence of hepatitis A and E virus infection in school children of an Amazonian municipality in Mato Grosso State. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2002, 35, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.M.; Oliveira, J.M.; Vitral, C.L.; Vieira, K.A.; Pinto, M.A.; Souto, F.J. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies in individuals exposed to swine in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, V.O.L.; Tejada-Strop, A.; Weis, S.M.S.; et al. Evidence of hepatitis E virus infections among persons who use crack cocaine from the Midwest region of Brazil. J. Med. Virol. 2019, 91, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis-Torres, S.M.D.S.; França, A.O.; Granato, C.; Passarini, A.; Motta-Castro, A.R.C. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus infection among volunteer blood donors in Central Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focaccia, R.; da Conceição, O.J.; Sette, H. Jr.; Sabino, E.; Bassit, L.; Nitrini, D.R.; et al. Estimated Prevalence of Viral Hepatitis in the General Population of the Municipality of São Paulo, Measured by a Serologic Survey of a Stratified, Randomized and Residence-Based Population. Braz J Infect Dis 1998, 2, 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçales, N.S.; Pinho, J.R.; Moreira, R.C.; et al. Hepatitis E virus immunoglobulin G antibodies in different populations in Campinas, Brazil. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2000, 7, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, T.; Passos, A.M.; Perez, R.M.; et al. Past and current hepatitis E virus infection in renal transplant patients. J. Med. Virol. 2014, 86, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos-Castilho, A.M.; de Sena, A.; Reinaldo, M.R.; Granato, C.F. Hepatitis E virus infection in Brazil: results of laboratory-based surveillance from 1998 to 2013. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2015, 48, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos-Castilho, A.M.; Reinaldo, M.R.; Sena, A.; Granato, C.F.H. High prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies in Sao Paulo, Southeastern Brazil: analysis of a group of blood donors representative of the general population. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 21, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricks, G.; Senise, J.F.; Pott Junior, H.; et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus in chronic hepatitis C in Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.; Gomes-Gouvêa, M.S.; Lisboa-Neto, G.; et al. Serological and molecular markers of hepatitis E virus infection in HIV-infected patients in Brazil. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricks, G.; Senise, J.F.; Pott-Jr, H.; et al. Previous hepatitis E virus infection, cirrhosis and insulin resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, D.C.A.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Haddad, S.K.; et al. Declining prevalence of hepatitis A and silent circulation of hepatitis E virus infection in southeastern Brazil. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, D.D.; Luna, L.K.S.; Passarini, A.; et al. Hepatitis E virus infection among patients with altered levels of alanine aminotransferase. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 25, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, A.C.P.; Gouvea, M.G.; Ferreira, A.C.; et al. The impact of hepatitis E infection on hepatic fibrosis in liver transplanted patients for hepatitis C infection. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 25, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitelli, P.M.Y.; Gomes-Gouvêa, M.; Mazo, D.F.; et al. Hepatitis E virus infection increases the risk of diabetes and severity of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2021, 76, e3270. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, L.B.; Reche, L.A.; Nastri, A.C.S.S.; et al. Acute Hepatitis Related to Hepatitis E Virus Genotype 3f Infection in Brazil. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicker, M.; Pinho, J.R.R.; Welter, E.A.R.; et al. The Risk of Reinfection or Primary Hepatitis E Virus Infection at a Liver Transplant Center in Brazil: An Observational Cohort Study. Viruses 2024, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinta, K.S.; Liberto, M.I.; de Paula, V.S.; Yoshida, C.F.; Gaspar, A.M. Hepatitis E virus infection in selected Brazilian populations. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2001, 96, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.C.; Souto, F.J.; Santos, D.R.; Vitral, C.L.; Gaspar, A.M. Seroepidemiological markers of enterically transmitted viral hepatitis A and E in individuals living in a community located in the North Area of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2002, 97, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoliero, A.L.; Bonametti, A.M.; Morimoto, H.K.; Matsuo, T.; Reiche, E.M. Seroprevalence for hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection among volunteer blood donors of the Regional Blood Bank of Londrina, State of Paraná, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2006, 48, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardtke, S.; Rocco, R.; Ogata, J.; et al. Risk factors and seroprevalence of hepatitis E evaluated in frozen-serum samples (2002–2003) of pregnant women compared with female blood donors in a Southern region of Brazil. J. Med. Virol. 2018, 90, 1856–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss da Silva, C.; Oliveira, J.M.; Mendoza-Sassi, R.A.; et al. Detection and characterization of hepatitis E virus genotype 3 in HIV-infected patients and blood donors from southern Brazil. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.B.; Gouvêa, M.S.G.; Chuffi, S.; et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus in risk populations and blood donors in a referral hospital in the south of Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzetto, R.; Klein, R.L.; Erpen, L.M.S.; et al. Unusual high prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in South Brazil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.J.; Gomes-Gouvêa, M.S.; Soares, M.d.C.; et al. HEV infection in swine from Eastern Brazilian Amazon: evidence of co-infection by different subtypes. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 35, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Lopes, K.G.S.; Cunha, D.S.; et al. Risk Analysis and Occurrence of Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) in Domestic Swine in Northeast Brazil. Food Environ. Virol. 2017, 9, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Dos Santos, D.R.; Durães-Carvalho, R.; et al. Evolutionary study of potentially zoonotic hepatitis E virus genotype 3 from swine in Northeast Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2019, 114, e180585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Lana, M.V.; Gardinali, N.R.; da Cruz, R.A.; et al. Evaluation of hepatitis E virus infection between different production systems of pigs in Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.G.; Silveira, S.; Schenkel, D.M.; et al. Detection of hepatitis E virus genotype 3 in pigs from subsistence farms in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 58, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitral, C.L.; Pinto, M.A.; Lewis-Ximenez, L.L.; Khudyakov, Y.E.; dos Santos, D.R.; Gaspar, A.M. Serological evidence of hepatitis E virus infection in different animal species from the Southeast of Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2005, 100, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.R.; de Paula, V.S.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Marchevsky, R.S.; Pinto, M.A. Hepatitis E virus in swine and effluent samples from slaughterhouses in Brazil. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 149, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.R.; Mendes, G.S.; Pena, G.P.A.; Santos, N. Hepatitis E virus infection of slaughtered healthy pigs in Brazil. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, A.; Metorima, C.S.; Miyagi, S.A.T.; Sousa, A.O.; Peyser, A.V.; Castro, A.M.M.G.; et al. High genetic diversity of hepatitis E virus in swine in São Paulo State, Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2021, 73, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardinali, N.R.; Barry, A.F.; da Silva, P.F.; de Souza, C.; Alfieri, A.F.; Alfieri, A.A. Molecular detection and characterization of hepatitis E virus in naturally infected pigs from Brazilian herds. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 1515–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos-Castilho, A.M.; Granato, C.F.H. High frequency of hepatitis E virus infection in swine from South Brazil and close similarity to human HEV isolates. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.S.; Silveira, S.; Caron, V.S.; et al. Backyard pigs are a reservoir of zoonotic hepatitis E virus in southern Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 112, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariz, C. A.; Braga, C.; Albuquerque, M.F. P. M.; Luna, C. F.; Salustiano, D. M.; Freire, N. M.; Morais, C. N. L.; Lopes, E. P. Occurrence of hepatitis B and C virus infection in socioeconomic population strata from Recife, Pernambuco, Northeast Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Epidemiologia 2024, 27, e240033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 7, 396–415.

- Villalobos, N.V.F.; Kessel, B.; Rodiah, I.; Ott, J.J.; Lange, B.; Krause, G. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus infection in the Americas: Estimates from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J. M.; Dos Santos, D. R. L.; Pinto, M. A. Hepatitis E Virus Research in Brazil: Looking Back and Forwards. Viruses 2023, 15, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, J.; Otto, B.; Madden, R.G.; Webb, G.; Woolson, K.L.; Kriston, L.; et al. Hepatitis E seroprevalence in Europe: a meta-analysis. Viruses 2016, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brazil Region | Author/Year | Type of study | Selected population | Epidemiological Peculiarities | Sample size |

Anti-HEV prevalence |

RNA | Genotype | |

| IgG n (%) | IgM n (%) | ||||||||

| North | |||||||||

| Acre | Vitral CL et al., 2014 [24] |

Retrospective cross-sectional | Residents of an agricultural settlement in 2004 | Age > 21 years | 388 | 50 12,8% |

7 16,3% |

n/a | n/a |

| Amazônia/ Rondônia | Vasconcelos MP et al., 2024 [25] | Cross-sectional | Yanomani Indians Urban and rural areas |

HEV in urban areas (2.97%), rural areas (14.2%) and village areas (2.8%) | 811 |

556,8% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Pará | Souza AJS et al., 2018 [26] | Cross-sectional | Afro-descendant community | Young men reported eating bushmeat | 535 | 3 0,5% |

6 1,1% |

negative | n/a |

| Souza AJS et al., 2019 [27] | Cross-sectional | Suspected cases of acute hepatitis | Male gender (55.2%) | 318 | 29 9,1% |

16 5,0% |

Negative | n/a | |

| Nascimento RS et al., 2021 [28] | Cross-sectional | Crack cocaine users | Poorer and homeless; longer use of crack cocaine | 437 | 79 18,1% |

6 1,4% |

Positive | 3c | |

| Northeast | |||||||||

| Bahia | Paraná R et al., 1997 [15] | Retrospective cross-sectional | 200 Blood donors 392 hemodialyzed |

Blood donors | 200 | 4 2% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Paraná R et al. 1999 [29] | Cross-sectional | Acute sporadic non-A, non-B (NANB) | Aminotransferses elevation. | 43 |

512% |

negative | n/a | n/a | |

| Lyra AC et al., 2005 [30] | Cross-sectional | Patients with acute viral hepatitis | Higher prevalence of HEV in patients with acute hepatitis | 73 | 21 28,8% |

56.8% |

n/a | n/a | |

| Pernambuco | Passos-Castilho AM et al., 2016 [31] | Retrospective cross-sectional | Patients with schistosomiasis mansoni | Patients treated at a referral hospital with advanced forms of the disease | 80 | 15 18,8% |

negative | negative | n/a |

| Bezerra LA et al., 2019 [32] | Cross-sectional | People living with HIV/AIDS | Higher HIV infection time | 366 | 15 4,1% |

n/a | Negative | n/a | |

| Cunha GG et al., 2022 [33] | Cross-sectional | Blood candidates and donors | All male gender, consumption of pork and chicken | 996 | 9 0,9% |

n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Araújo LRMG et al., 2024 [34] | Cross-sectional | Patients with chronic liver disease | Contact with pigs and more advanced liver disease | 227 | 7 3,08% |

n/a | negative | n/a | |

| Gomes CTO et al., 2024 [35] | Retrospective cross-sectional | Patients with schistosomiasis mansoni | More advanced periportal fibrosis (Niamey D/E/F) | 286 | 15 5.24% |

Negative | Negative | n/a | |

| Piaui | Silva-Sampaio JP et al., 2025 [36] | Cross-sectional | Blood donors | 66.7% male gender, 75% age ≥ 30 years |

890 | 12 1,35% |

1 0,1% |

negative | n/a |

| Central West | |||||||||

| Goiás | Martins RM et al., 2014 [37] | Prevalence survey | Recyclable material collectors | Contact with human feces (87.5%) and animal feces (75%) | 431 | 22 5,1% |

3 0,7% |

negative | n/a |

| Freitas NR et al., 2016 [38] | Cross-sectional | Patients with acute viral hepatitis | Consumo carne de porco (95%) e animais selvagens (75%) | 379 | 20 5,3% |

1 0,3% |

negative | n/a | |

| Freitas NR et al., 2017 [39] | Cross-sectional | Rural settlement | 75% male gender, Time in rural settlement > 5 years | 464 | 16 3,4% |

n/a | negative | n/a | |

| Oliveira JMNS et al., 2018 [40] | Cohort | kidney transplant recipients | 100% Previous hemodialysis, Consumption of wild animal meat (87.5%) | 316 | 8 2,5% |

1 0,3% |

negative | n/a | |

| Teles AS et al. 2023 [41] | Cross-sectional | Recyclers, immigrants, refugees, and homeless people | Homeless; Recyclers | 459 | 4 0,87% |

1 0,2% |

negative | ||

| Mato Grosso | Assis SB et al., 2002 [42] | Prevalence survey | School children | Absence of sanitary sewage. | 487 | 22 4,5% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Silva SM et al., 2022 [43] | Cross-sectional | Pig handlers | age ≥ 50 years, Longer exposure to pigs | 310 | 26 8,4% |

n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | Castro VOL et al., 2018 [44] | Cross-sectional | Crack users | Low education level (73.7%), unprotected sexual intercourse | 698 | 99 14,2% |

2 0,28% |

negative | n/a |

| Weis-Torres SMDS et al., 2022 [45] | Retrospective cross-sectional | Blood donors | 75% male, 70% age ≥ 30 years; Lack of sewage system | 250 | 16 6.4% |

Negative | n/a | n/a | |

| Southeast | |||||||||

| São Paulo | Focaccia R et al.,1998 [46] | Prevalence survey | General population | 1,059 | 1.68% | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Gonçales NS et al., 2000 [47] | Cross-sectional | Blood donors and staff at a university hospital, | blood donors with elevated ALT, and cleaning staff | 375 | 18 4,8% |

n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Hering T et al., 2014 [48] | Cross-sectional | Kidney transplant | Transplant patients with elevated aminotransferases | 192 | 28 15% |

n/a | 20 10% |

n/a | |

| Passos-Castilho AM et al., 2015 [49] | Retrospective cross-sectional | Patients with clinical suspicion of HEV | age ≥ 40 years | 2,271 | 47 2,1% |

27 4,9% |

1 | 3b | |

| Passos-Castilho AM et al., 2017 [50] | Cross-sectional | Blood donors | age ≥45 years | 500 | 49 9,8% |

1 | negative | n/a | |

| Bricks G et al., 2018 [51] | Cross-sectional | Chronic HCV patients | contact with pigs and consumption of pork | 618 | 63 10,2% |

negative | n/a | n/a | |

| Ferreira AC et al., 2018 [52] | Cross-sectional | People living with HIV | age ≥40 years | 354 | 38 10,7% |

51,4% |

negative | n/a | |

| Bricks G et al., 2019 [53] | Cross-sectional | Chronic HCV patients | age ≥60 years; contact with pigs | 618 | 63 10,2% |

negative | n/a | n/a | |

| Araújo DCA et al., 2020 [54] | Cross-sectional | Residents of a small municipality in São Paulo | consumption of raw meat | 248 | 50 20,7% |

negative | n/a | n/a | |

| Conte DD et al., 2021 [55] | Cross-sectional | Patients in the Emergency Room with altered levels of Alanine aminotransferases | Altered levels of Alanine aminotransferases | 401 | n/a | 2 of 90 2.2% |

16of 311 5.1% |

n/a | |

| Moraes ACP et al., 2021 [56] | Cohort | Liver transplants | HBV/HCV coinfected | 294 | 24 8.2% |

6 2% |

17 5,8% |

n/a | |

| Zitelli PMY et al., 2021 [57] | Cross-sectional | Chronic HCV patients | More advanced liver disease; more Type-2DM, | 181 | 22 12% |

3 1,6% |

9 4,9% |

n/a | |

| Ribeiro LB et al., 2024 [58] | Cross-sectional | Patients with acute viral hepatitis | Elevated aminotransferases | 91 | 12 13.2% |

4 4.4% |

1 | 3f | |

| Zicker M et al., 2024 [59] | Prospective | Liver transplanted and donors | n/a | 190 | 19 10% |

1 0.53% |

negative | n/a | |

| Rio de Janeiro | Trinta KS et al., 2001 [60] | Retrospective cross-sectional | acute viral hepatitis; hemodialysis; intravenous drug users; blood donors; | n/a | 1,115 | 2.1% acute viral hepatitis 6.2% hemodialysis; 11.8% UDIVs; 4,.3% blood donors |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Santos DC et al., 2002 [61] | Cross-sectional | Manguinhos Community | age ≥40 years | 699 | 17 2.4% |

n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| South | |||||||||

| Paraná | Bortoliero AL et al., 2006 [62] | Cross-sectional | Blood donors | There was no association with sociodemographic variables | 996 | 23 2.3% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Hardtke S et al., 2018 [63] | Cross-sectional | 209 pregnant women; 199 female blood donor | age ≥40 years; >3 number of pregnancies | 408 | 91 22,5% |

n/a | negative | n/a | |

| Santa Catarina | Passos-Castilho AM et al., 2016 [18] | Cross-sectional | Blood donors | 300 | 30 10% |

1 0,3% |

negative | n/a | |

| Rio Grande do Sul | Moss da Silva SC et al., 2019 [64] | Cross-sectional | PVHIV; Blood donors | age ≥40 years; poor sanitation; alcohol use |

601 | 42 6,98% |

n/a | 8 1,33% |

3 |

| Costa et al., 2021 [65] | Cross-sectional | cirrhosis; crack users; liver transplanted; blood donors | higher in cirrhosis; crack users; liver transplanted patients and blood donors | 400 | 78 19,5% |

6 1,5% |

negative | n/a | |

| Zorzeto R et al., 2021 [66] | Cross-sectional | Blood samples were from laboratories | age ≥40 years | 3,000 | 1,783 59,4% |

n/a | negative | n/a | |

| Brazil Region | State | Author/Year | Herd Characteristics | Biological sample tested |

Total (n=) |

Prevalence HEV | RNA | Genotype | |

|

IgG n(%) |

IgM n(%) |

||||||||

| North | Pará | Souza AJ et al, 2012 [67] | Six-month-old pigs from a licensed slaughterhouse (60%) and a slaughterhouse not registered with health regulatory agencies (40%). Samples collected during slaughter. | Serum, feces and liver | 151 | 13 8.6% |

0 | 15* 9.9% |

3c; 3f |

| Northeast | Pernambuco | Oliveira-Filho EF et al., 2017 [68] | Coming from a slaughterhouse located in the metropolitan region of Recife (30%) and farms in the rural region of the state (70%) | Serum | 325 | 266 82% |

- | n/a | n/a |

| Pernambuco | Oliveira-Filho EF et al., 2019 [69] | Animals aged two to six months, from farms that use intensive and extensive production systems. | Feces | 119 | - | - | 2 (1.68%) |

3f |

|

| Central West | Mato Grosso | Costa Lana et al., 2014 [70] | Four-month-old animals from large-scale farms (50%) and family farms (50%). Overall, 18 (72%) of the 25 pigs presented microscopic liver lesions, characterized by fibrosis and portal inflammation. | Bile, liver and feces | 25 | - | - | 15** 83,3% |

3b;3f |

| Mato Grosso | Campos CG et al., 2018 [71] | Growing piglets of both sexes, between three and four months of age, and breeding females, between eight and twenty-four months of age, from subsistence farms. | Serum and feces | 150 | - | - | 12 8% |

3d; 3h;3i |

|

| Southeast | Rio de Janeiro | Vitral CL et al., 2005 [72] | Pigs ranging in age from 1 to > 25 weeks in four commercial herds | Serum | 357 | 227 63.6% |

- | n/a | n/a |

| Rio de janeiro | dos Santos DR et al., 2011 [73] | Healthy animals aged > five months, from three legal slaughterhouses. | Bile | 115 | - | - | 11*** 9.6% |

3b |

|

| Minas Gerais | Amorim AR et al., 2018 [74] | Healthy animals for slaughter at a state slaughterhouse. No macroscopic lesions were observed in the livers of slaughtered pigs during bile collection. | Bile | 335 | - | - | 51 15.2% |

3c;3i |

|

| São Paulo | Cortez A et al., 2021 [75] | Samples from a state swine biobank. | Feces | 89 | - | - | 7 7.86% |

3b; 3h; 3j |

|

| South | Paraná | Gardinali NR et al., 2012 [76] | Samples came from maturation cycle farms (58.3%) and grow-to-slaughter farms (41.7%). All pigs were asymptomatic. | Feces | 170 | - | - | 26 15.3% |

3b |

| Paraná | Passos-Castilho AM et al., 2017 [77] | Animals aged between four and 16 weeks old from a small rural property in the region. | Feces | 170 | - | - | 34 20% |

3b |

|

| Rio Grande do Sul | da Silva MS et al., 2018 [78] | Animals from farms located near peri-urban areas or landfills, indigenous reservations, and farms that feed pigs with food scraps. Samples from two different periods were analyzed: 2012 (50.6%) and 2014 (49.4%) | Serum | 1444 | 1034 71.6% |

- | 6**** 0.8% |

3b; 3c; 3h |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).