Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sensitization to house dust mites (HDM) in early life is a risk factor for poor respiratory allergy outcomes. We analyzed characteristics of HDM sIgE positive infants and compare with negative infants under the age of 2. Of the 1,793 infants who tested for HDM sIgE, 96 (5.4%) had HDM sensitization. In the HDM (+) group, atopic dermatitis was 74.0% (90.9% at the age of less than 12 months), food allergies 57.3% (<12 months, 100%), egg white sensitization 71.9% (<12 months, 90.9%), and cow’s milk sensitization 56.3% (<12 months, 81.8%). Atopic dermatitis, food allergy, ≥4 episodes of wheezing, physician-diagnosed asthma, allergic rhinitis, egg white sensitization, cow’s milk sensitization, and sensitization to three or more food allergens were significantly more frequent in the HDM (+) group compared to the HDM (-) group. The HDM sIgE and total IgE levels and HDM sIgE and egg white sIgE levels showed significant correlations. HDM sensitization in infants is mostly accompanied by atopic dermatitis and egg white sensitization. Early sensitization to HDMs should be carefully observed in infants with atopic dermatitis and food allergies, especially those with high total IgE and egg white sIgE.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Target Population

Methods

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Clinical Characteristics of the HDM-Sensitized Infants

Laboratory Data of HDM-Sensitized Infants

Comparison Between the HDM (+) and HDM (-) Groups

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDM | house dust mites |

References

- Miyamoto T, Oshima S, Ishizaki T, Sato SH. Allergenic identity between the common floor mite (Dermatophagoides farinae Hughes, 1961) and house dust as a causative antigen in bronchial asthma. J Allergy 1968;42(1):14-28.

- Sarsfield JK. Role of house-dust mites in childhood asthma. Arch Dis Child 1974;49(9):711-5.

- Ree HI, Jeon SH, Lee IY, Hong CS, Lee DK. Fauna and geographical distribution of house dust mites in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1997;35(1):9-17.

- Kim J, Hahm MI, Lee SY, Kim WK, Chae Y, Park YM, et al. Sensitization to aeroallergens in Korean children: a population-based study in 2010. J Korean Med Sci 2011;26(9):1165-72.

- Jeong KY, Park JW, Hong CS. House dust mite allergy in Korea: the most important inhalant allergen in current and future. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2012;4(6):313-25.

- Park SC, Hwang CS, Chung HJ, Purev M, Al Sharhan SS, Cho HJ, et al. Geographic and demographic variations of inhalant allergen sensitization in Koreans and non-Koreans. Allergol Int 2019;68(1):68-76.

- Dharmage SC, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, Burgess JA, Allen KJ, Abramson MJ. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march revisited. Allergy 2014;69(1):17-27.

- Gabryszewski SJ, Hill DA. One march, many paths: Insights into allergic march trajectories. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021.

- Eapen AA, Kim H. The Phenotype of the Food-Allergic Patient. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2021;41(2):165-75.

- Calderón MA, Linneberg A, Kleine-Tebbe J, De Blay F, Hernandez Fernandez de Rojas D, Virchow JC, et al. Respiratory allergy caused by house dust mites: What do we really know? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136(1):38-48.

- Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, Willart MA, Germain RN, Lambrecht BN. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med 2009;15(4):410-6.

- Sporik R, Holgate ST, Platts-Mills TAE, Cogswell JJ. Exposure to House-Dust Mite Allergen (Der p I) and the Development of Asthma in Childhood. 1990;323(8):502-7.

- Brussee JE, Smit HA, van Strien RT, Corver K, Kerkhof M, Wijga AH, et al. Allergen exposure in infancy and the development of sensitization, wheeze, and asthma at 4 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115(5):946-52.

- Celedón JC, Milton DK, Ramsey CD, Litonjua AA, Ryan L, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Exposure to dust mite allergen and endotoxin in early life and asthma and atopy in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(1):144-9.

- Su KW, Chiu CY, Tsai MH, Liao SL, Chen LC, Hua MC, et al. Asymptomatic toddlers with house dust mite sensitization at risk of asthma and abnormal lung functions at age 7 years. World Allergy Organ J 2019;12(9):100056.

- Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Niggemann B, Grüber C, Wahn U. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet 2006;368(9537):763-70.

- De Bilderling G, Mathot M, Agustsson S, Tuerlinckx D, Jamart J, Bodart E. Early skin sensitization to aeroallergens. 2008;38(4):643-8.

- Casas L, Sunyer J, Tischer C, Gehring U, Wickman M, Garcia-Esteban R, et al. Early-life house dust mite allergens, childhood mite sensitization, and respiratory outcomes. Allergy 2015;70(7):820-7.

- Lau S, Illi S, Sommerfeld C, Niggemann B, Bergmann R, von Mutius E, et al. Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: a cohort study. The Lancet 2000;356(9239):1392-7.

- Wahn U, Bergmann R, Kulig M, Forster J, Bauer CP. The natural course of sensitisation and atopic disease in infancy and childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1997;8(10 Suppl):16-20.

- Holt PG, Jones CA. The development of the immune system during pregnancy and early life. Allergy 2000;55(8):688-97.

- Brough HA, Liu AH, Sicherer S, Makinson K, Douiri A, Brown SJ, et al. Atopic dermatitis increases the effect of exposure to peanut antigen in dust on peanut sensitization and likely peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(1):164-70.

- Tham EH, Rajakulendran M, Lee BW, Van Bever HPS. Epicutaneous sensitization to food allergens in atopic dermatitis: What do we know? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2020;31(1):7-18.

- Brough HA, Nadeau KC, Sindher SB, Alkotob SS, Chan S, Bahnson HT, et al. Epicutaneous sensitization in the development of food allergy: What is the evidence and how can this be prevented? Allergy 2020;75(9):2185-205.

- Boralevi F, Hubiche T, Léauté-Labrèze C, Saubusse E, Fayon M, Roul S, et al. Epicutaneous aeroallergen sensitization in atopic dermatitis infants—determining the role of epidermal barrier impairment. Allergy 2008;63(2):205-10.

- Kimura M, Meguro T, Ito Y, Tokunaga F, Hashiguchi A, Seto S. Close Positive Correlation between the Lymphocyte Response to Hen Egg White and House Dust Mites in Infants with Atopic Dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2015;166(3):161-9.

- Christiansen ES, Kjaer HF, Eller E, Bindslev-Jensen C, Høst A, Mortz CG, et al. Early-life sensitization to hen’s egg predicts asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis at 14 years of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017;28(8):776-83.

- Yoo Y, Perzanowski MS. Allergic sensitization and the environment: latest update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014;14(10):465.

- Jeon YH, Lee YJ, Sohn MH, Lee HR. Effects of Vacuuming Mattresses on Allergic Rhinitis Symptoms in Children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11(5):655-63.

| N (%) or mean ± SD | ||

|

Infants< 24 months (N=96) |

Infants< 12 months (N=11) |

|

| Age (months) | 17.2 ± 4.3 | 10.3 ± 0.9 |

| Male | 63 (64.6%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Doctor-diagnosed allergic disease | ||

| Atopic dermatitis | 71 (74.0%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Food allergy | 55 (57.3%) | 11 (100%) |

| Anaphylaxis | 10 (10.4%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Recurrent wheezing (≥ 4 times) | 31 (32.3%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Asthma | 23 (24.2%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 30 (31.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean ± SD | |

| Infants <24 months | Infants <12 months | |

| Total IgE* (kU/L) | 415.0 ± 674.1 | 368.2 ± 718.9 |

| HDM† sIgE‡ (kU/L) | 12.4 ± 23.6 | 13.3 ± 29.5 |

| Egg whitesensitization | 69 (75.0%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Cow’s milk sIgEsensitization | 54 (62.8%) | 9 (81.8%) |

|

Multiple food sensitization (≥ 3 food allergens) |

48 (51.1%) | 8 (72.7%) |

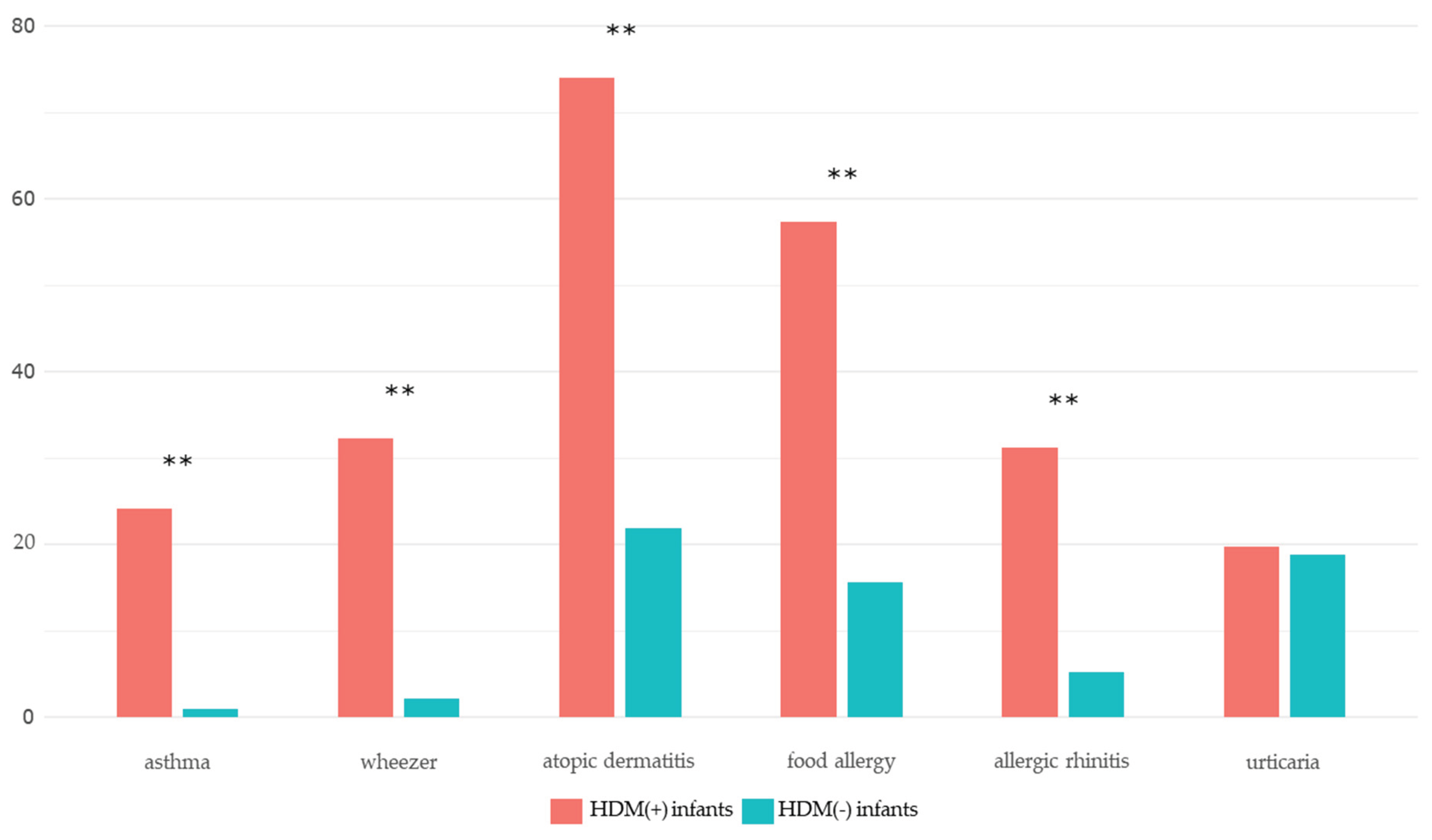

| Variables | HDM (+) group | HDM (−) group | P-value |

| Atopic dermatitis | 71 (74.0) | 21 (21.9) | <0.001*** |

| Food allergy | 55 (57.3) | 15 (15.6) | <0.001*** |

| Anaphylaxis | 10 (10.4) | 3 (3.1) | 0.096 |

| Recurrent wheezing (≥ 4 times) | 31 (32.3) | 2 (2.1) | <0.001*** |

| Asthma | 23 (24.2) | 1 (1.0) | <0.001*** |

| Allergic rhinitis | 30 (31.2) | 5 (5.2) | <0.001*** |

| Urticaria | 19 (19.8) | 18 (18.8) | 1.000 |

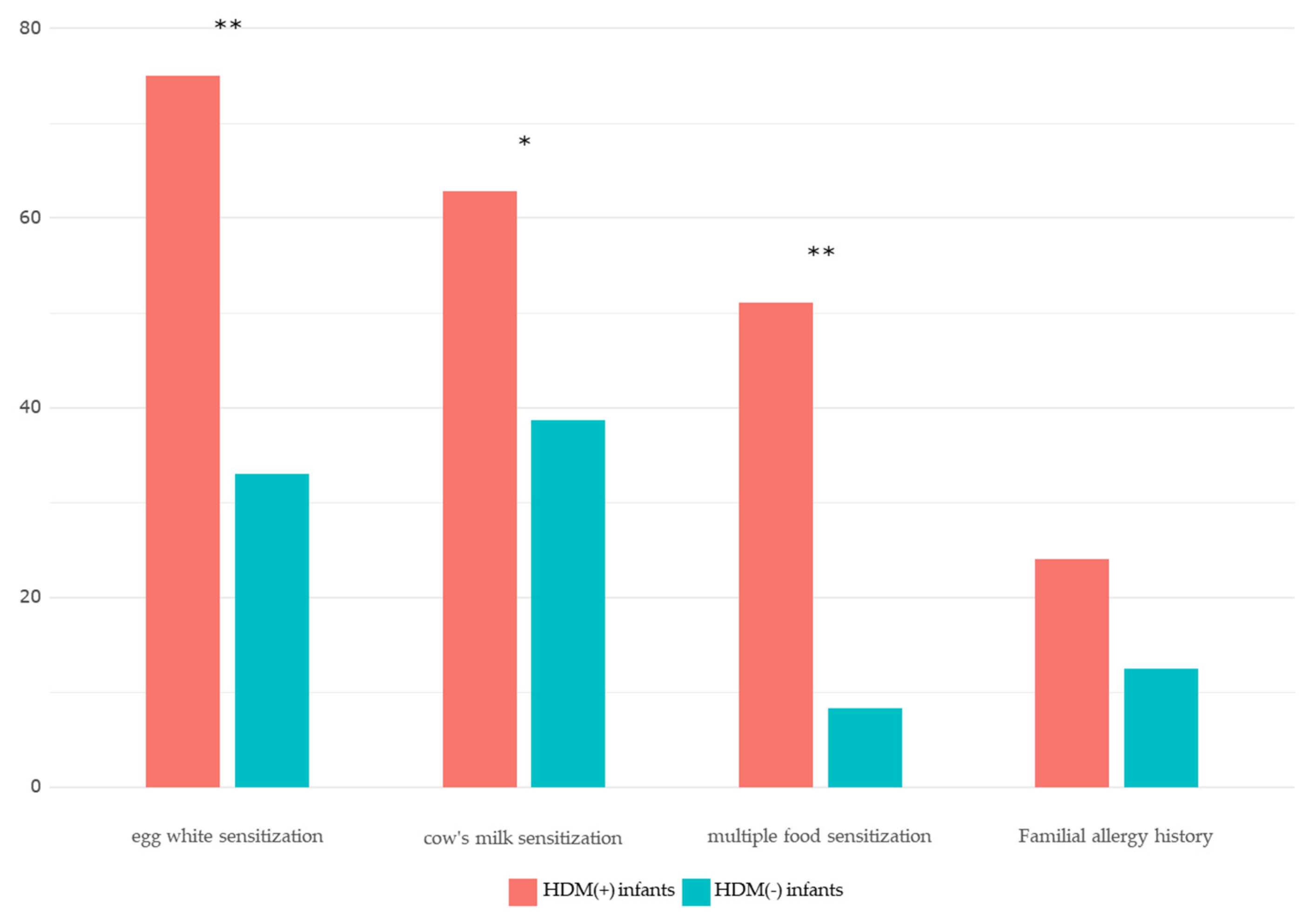

| Egg whitesensitization | 69 (75.0) | 31 (33.0) | <0.001*** |

| Milk sIgEsensitization | 54 (62.8) | 36 (38.7) | 0.007** |

|

Multiple foodsensitization (≥ 3 food allergens) |

48 (51.1) | 8 (8.3) | <0.001*** |

| Variables |

HDM (+) group (mean ± SD) |

HDM (−) group (mean ± SD) |

P-value |

| Log(total IgE+1) | 2.17 ± 0.64 | 1.57 ± 0.66 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Egg white sIgE (kU/L) | 16.13 ± 29.65 | 1.15 ± 3.30 | ≤0.001 |

| Cow’s milk sIgE (kU/L) | 6.08 ± 16.20 | 0.67 ± 1.36 | 0.001 |

|

Total IgE coefficient (P-value) |

Egg white sIgE coefficient (P-value) |

Cow’s milk sIgE coefficient (P-value) |

|

| HDM sIgE | 0.326 (0.002) | 0.312 (0.002) | 0.215 (0.047) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).