Materials and Methods

Our observational study was not randomized and involved a prospective evaluation of a cohort of 74 adult patients with multiple myeloma and indications for treatment including the antiangiogenic drug thalidomide in first-line therapy. Patients were treated at the Hematology Clinic of the Military Medical Institute in Warsaw.

The study was approved by the ethics committee KB/234/18 on January 10, 2018. The purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants, and their verbal and written informed consent was obtained. However, it should be emphasized that all patients eligible for the study had full indications for standard treatment in 2018-2019, i.e., including the use of thalidomide in first-line therapy.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has developed guidelines for the diagnosis, therapy, monitoring, and supportive care of multiple myeloma (MM). An update covering therapeutic management was published in January 2018 [

1]. NCCN experts classified drugs used in MM therapy—both for newly diagnosed patients and those with refractory/relapsed myeloma—into three groups: “preferred,” “other recommended,” and “useful in specific circumstances.” Patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ND MM) eligible for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation had preferred regimens in triple-drug therapies based on the use of bortezomib: bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd) and bortezomib/ cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone (VCd). The VCd regimen was considered the treatment of choice in patients with acute kidney injury, with the possibility of switching to VRd after improvement in kidney function.

In 2018-2019, the situation in Poland was different. First of all, it should be emphasized that first-line treatment with lenalidomide, recommended by the NCCN, was not reimbursed in Poland. According to the guidelines of the Polish Myeloma Group published in 2017, patients eligible for autoHSCT should have received induction therapy according to the VTD bortezomib/thalidomide/dexamethasone), VCD (bortezomib/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone), or PAD (bortezomib/doxorubicin/dexamethasone) protocols.

In our study, we only considered patients who were eligible for treatment with VTD or VCD therapy.

General eligibility criteria: (1) age over 18 years; (2) performance status 0–2 according to the ECOG scale (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scale); (3) diagnosis of multiple myeloma; (4) presence of indications for treatment in accordance with the guidelines Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [

1] (5) no contraindications to the use of the drug in accordance with the current summary of product characteristics; (6) no hypersensitivity to any of the drugs or any of the excipients of the drug; (7) exclusion of pregnancy and lactation; (8) patient consent to use contraception in accordance with the current summary of product characteristics; (9) no active and serious infections; and (10) no significant comorbidities or clinical conditions that are contraindications to therapy.

Important exclusion criteria: (1) occurrence of hypersensitivity symptoms to any of the drugs used or any of the excipients of the drug (2) pregnancy or breastfeeding; and (3) occurrence of diseases or conditions which, in the opinion of the attending physician, prevent continuation of treatment.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study group in terms of gender, age, ECOG performance status, and clinical stage of disease according to the Salmon-Durie classification.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study group in terms of gender, age, ECOG performance status, and clinical stage of disease according to the Salmon-Durie classification.

| Cohort |

74 |

| Sex |

|

| female |

47,3% |

| male |

52,7% |

| Age |

|

| mean |

55,5 |

| range |

48-61 |

| Diagnosis |

|

| Myeloma multiplex |

100% |

| ECOG |

|

| 0 |

2 (2,7%) |

| 1 |

42 (56,76%) |

| 2 |

30 (40,54%) |

| Durie-Salmon classification |

|

| I |

0 |

| II |

9 (12,14%) |

| III |

65 (87,86%) |

All patients underwent standard initial examinations to assess their condition, including a medical examination, physical examination, and biochemical tests, particularly those related to kidney function and electrolyte levels (sodium, potassium, calcium). Imaging tests, especially bone tomography to assess the bone osteolysis process, and bone marrow examination were also performed. The bone marrow was subjected to both a standard assessment to determine the degree of plasma cell infiltration and an additional examination of endothelial cell activity. The test was performed using flow cytometry.

Statistical Methodology

All statistical calculations were performed using the statistical package TIBCO Software Inc. (2017). Statistica (data analysis software system), version 13.

http://statistica.io.

Quantitative variables were characterized using arithmetic mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum values (range), and 95% CI (confidence interval). Qualitative variables were presented using counts and percentages (percentage).

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check whether the quantitative variable came from a normally distributed population. The Levene (Brown-Forsythe) test was used to test the hypothesis of equal variances.

The significance of differences between two groups was examined using significance tests: Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The significance of differences between more than two groups was checked using the F test (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test. In the case of statistically significant differences between groups, post hoc tests were used (Tukey’s test for F, Dunn’s test for Kruskal-Wallis).

In order to determine the relationship, strength, and direction between variables, correlation analysis was used to calculate Pearson and/or Spearman correlation coefficients. In all calculations, p=0.05 was taken as the significance level.

Flow Cytometry Medodology

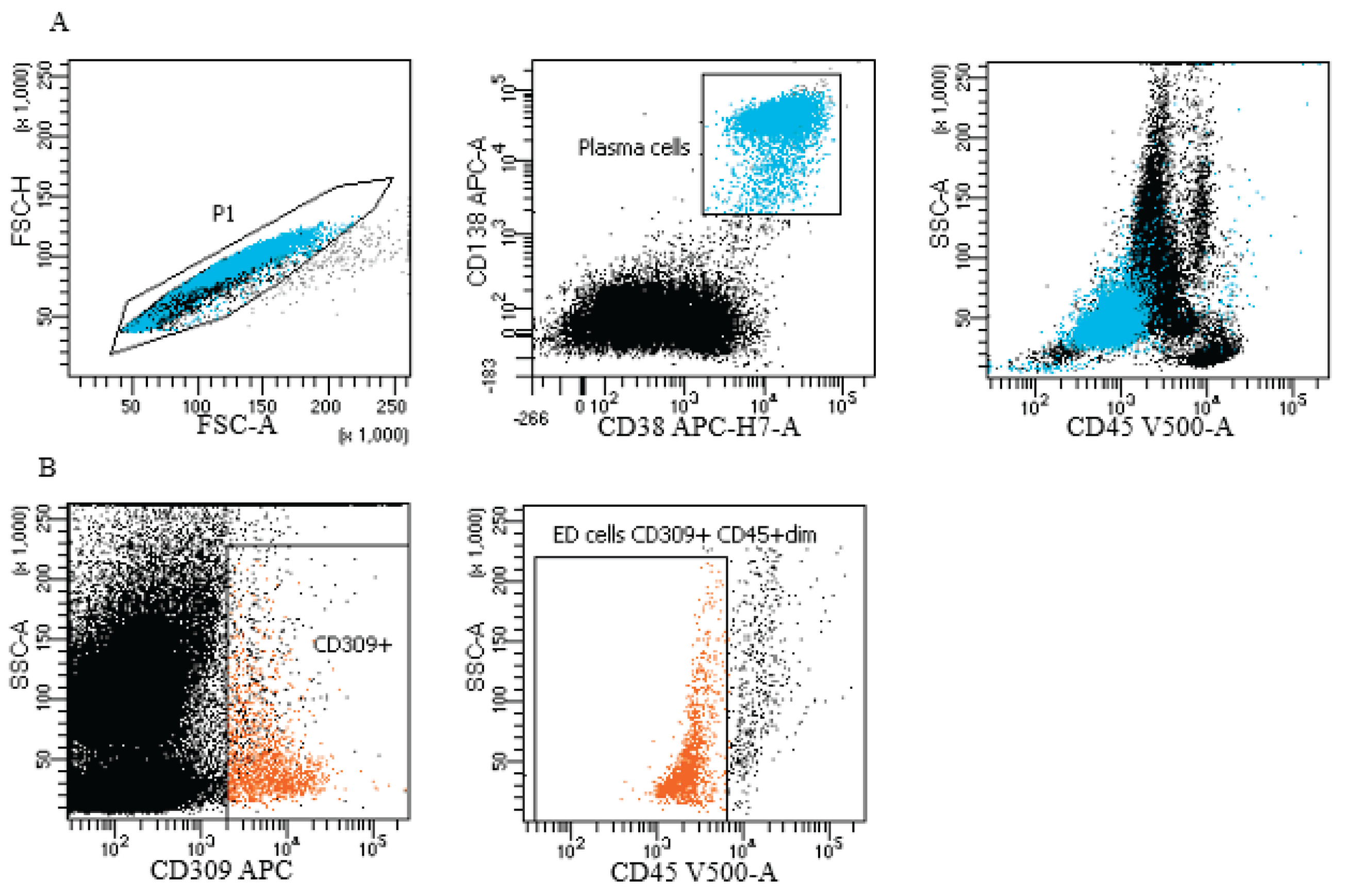

Plasma cells and endothelial cells were identified by evaluation of surface and intracellular antigens by flow cytometry using FACS Canto II BD (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). An 8-color panel of monoclonal antibodies was used. Cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies: CD45-V500, CD19 PE-Cy7, CD138-APC, CD38-APC-H7, CD20-V450, CD309-APC (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were analyzed within 2 h. For the detection of intracellular markers: lambda-FITC, kappa-PE (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), an additional step was performed with IntraStain (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) to fix and permeabilize the membrane. At least 200,000 events were collected for each sample. Data were analyzed using DIVA Analysis 8.0.1 software (Becton Dickinson) and Infinicyt 1.8 flow cytometry (Cytognos, Salamanca, Spain). Internal quality control of the cytometer was performed using CS&T IVD Beads BD FACS Diva (Becton Dickinson), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Plasma cells: CD45+dim CD138+ CD38+. Endothelial cells: CD45+dim CD309+ CD138

Figure 1.

Representative gating strategy in study group for plasma cells and endothelial cells (ED cells). (A) Plasma cells (blue color) gating strategy: FSC-A vs. FSC-H plot: Gating the cells that have an equal area and height, thus removing clumps (greater FSC-A relative to FSC-H) and debris (very low FSC) (P1 gate). CD138 APC vs. CD38 APC-H7-A plot: selection of plasma cells based on their expression of antigens. Location of plasma cells on the SSC-A vs CD45 V500-A plot. (B) Endothelial cells (orange color) gating strategy: dot plots of endothelial cells based on their SSC/CD309 APC properties, the next step - selection of endothelial cells on the SSC-A/CD45 V500-A plot (phenotypes of cells described in section: material and method).

Figure 1.

Representative gating strategy in study group for plasma cells and endothelial cells (ED cells). (A) Plasma cells (blue color) gating strategy: FSC-A vs. FSC-H plot: Gating the cells that have an equal area and height, thus removing clumps (greater FSC-A relative to FSC-H) and debris (very low FSC) (P1 gate). CD138 APC vs. CD38 APC-H7-A plot: selection of plasma cells based on their expression of antigens. Location of plasma cells on the SSC-A vs CD45 V500-A plot. (B) Endothelial cells (orange color) gating strategy: dot plots of endothelial cells based on their SSC/CD309 APC properties, the next step - selection of endothelial cells on the SSC-A/CD45 V500-A plot (phenotypes of cells described in section: material and method).

Results

Seventy-four patients with multiple myeloma were observed. All patients were eligible for VTD or VCD treatment. VCD therapy was used in 45 patients (60.81%), and VTD therapy was used in 29 patients (39.19%). In all patients, first-line therapy was completed with high-dose chemotherapy using melphalan at a dose of 100-200 mg/m2 as monotherapy, supported by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoPBSCT). In the study cohort, the percentage of women and men was 47.3% and 52.7%, respectively. The average age of patients was 55.5 years (range 48-61 years). Younger patients without serious comorbidities were specifically selected for our observation so that the predicted survival time, excluding hematological disease, would not be less than 10 years. All patients had diagnosed multiple myeloma. The stage of the disease was assessed according to the Salomon-Durie classification and was stage 2 in 13.1% of cases and stage 3 in 86.9% of cases. Patients with osteolytic bone lesions above 2 foci accounted for 84.1%, and those with 2 or fewer foci accounted for 15.9%.

Our study began in 2018 and the observation concerned patients with a confirmed diagnosis and initiation of treatment for multiple myeloma in 2018 and 2019. Subsequently, after completing treatment according to the above regimens, the patients underwent long-term observation. The type of remission achieved by the patients, whether it was complete or partial, was not analyzed, nor was the speed of disease recurrence after autologous transplantation as the final stage of first-line treatment. Among the 74 patients analyzed, 43 have died so far, i.e., between 2018 and the end of 2024, and 31 are still alive. The average survival time for deceased patients was 3.7 (0-6) years. Among the deceased patients, 26 (60.47%) received first-line VCD treatment, and 17 (39.53%) received VTD treatment.

As is well known, patients with myeloma often experience complications in the form of renal failure. Our study also took into account kidney function parameters. The mean creatinine value in the study cohort was 1.3 (range: 0.7–4.5), the mean eGFR value was 57 ml/min/m2 (range: 18–>90), the average Hb value was 11.8 (range: 9.8–14.1), the average HCT value was (14.8) (range: 0.1–51.1), the average platelet count was 84.0 (89.8) (range: 33.0–422.0), and the average hemoglobin concentration was 11.2 (2.5) (range: 7.5–15.7)

In our study patients, the value of endothelial cells in the bone marrow was assessed before the start of therapy. The test was performed using the immunophenotypic method. VTd and VCd therapy was conducted for 6 months until autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto PBSCT) was performed. We attempted to separate hematopoietic cells for autotransplantation after a maximum of four cycles of anti-myeloma therapy, as it is known that the use of thalidomide reduces the number of circulating CD34+ stem cells, which hinders the process of collecting cells from peripheral blood. Next, the survival of myeloma patients undergoing the above therapies was analyzed, and it was shown that patients with higher endothelial cell counts had higher mortality rates during long-term follow-up. In the group of deaths, the endothelial cell count was significantly higher (p=0.0235).

Table 1

Table 1.

Analysis of the relationship between endothelial cells values and mortality.

Table 1.

Analysis of the relationship between endothelial cells values and mortality.

| |

Death

(n=29) |

Survival

(n=16) |

P-value1

|

| endothelial cells |

|

|

0,0235 |

| (SD) |

0,835 (1,544) |

0,069 (0,043) |

|

| range |

0,022-5,500 |

0,003-0,134 |

|

| mediane (IQR) |

0,108 (0,777) |

0,071 (0,074) |

|

| 95%CI |

[0,248;1,423] |

[0,046;0,092] |

|

We also observed that patients who initially had osteolytic lesions > 2 also had higher endothelial cell counts (p=0.02120). However, analysis of endothelial cell counts in relation to survival in patients using antiangiogenic drugs showed that endothelial cell counts in this group of deaths were also significantly higher (p=0.0482).

Table 2.

Analysis of the relationship between endothelial cell values and survival in patients with osteolytic lesions >2.

Table 2.

Analysis of the relationship between endothelial cell values and survival in patients with osteolytic lesions >2.

| |

Zgon

(n=15) |

Przeżycie

(n=18) |

P-value1

|

| Endothelial cells |

|

|

0,0482 |

| (SD) |

0,743 (1,602) |

0,067 (0,047) |

|

| range |

0,023-5,500 |

0,003-0,127 |

|

| mediane (IQR) |

0,165 (0,614) |

0,075 (0,079) |

|

| 95%CI |

[-0,333;1,819] |

[0,030;0,103] |

|

Discussion

Understanding the molecular interactions between myeloma cells and non-hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow is also crucial for developing new strategies to improve the effectiveness of myeloma treatment.

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer characterized by the proliferation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow. Endothelial cells, in turn, are a type of cell that lines the inner surface of blood and lymphatic vessels, playing a key role in regulating blood flow, blood pressure, and the formation of new blood vessels. Multiple myeloma is still an incurable disease according to current knowledge, so any treatment method that improves prognosis, quality of life, and survival may ultimately represent progress in the treatment of this disease.

The relationship between myeloma and endothelial cells

In the context of myeloma, it has been found that endothelial cells interact with myeloma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. These interactions may promote the growth and survival of myeloma cells and contribute to the development of drug resistance. Endothelial cells can release various growth factors and cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates the proliferation of myeloma cells [

2]. In our study, we took into account the assessment of endothelial cells and the effect of the immunomodulatory antiangiogenic drug thalidomide on the survival of patients with myeloma. The drug thalidomide enhances the anti-tumor immune response, but also exhibits cytotoxic activity against multiple myeloma (MM) cells and inhibits tumor-associated angiogenesis [4]. Its newer counterparts have similar effects, but are free of many side effects.

The important role of angiogenesis in tumor development was initially described in solid tumors. It was not until the 1990s that this role was demonstrated in hematological malignancies, the first model of which was multiple myeloma [5]. Our study confirmed the importance of angiogenesis-inhibiting drugs in the treatment of multiple myeloma, as we demonstrated increased survival in patients with lower baseline endothelial cell counts and improved survival when antiangiogenic drugs were used. Morgan et al. [6] had already shown that continued use of thalidomide significantly improves PFS and may be associated with improved OS. Our observation confirmed this theory. Reyes et al. and Braunstein et al. emphasize the need to investigate the hypotheses that MM and EPC cells originate from multipotent progenitor cells [7,8] or MM stem cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation [9], or are altered by factors causing identical changes in myeloma cells and EPCs. Research is ongoing on the differentiation potential of single endothelial cells obtained from MM patients and comparing endothelial cells with cancerous plasma cells at the genetic level. The answers to these questions will allow us to better understand angiogenesis in myeloma and its significance for the treatment of this disease [10–12]. Rigolin et al. [13] published data on five patients with MM who had an identical 13q14 deletion in both circulating endothelial cells and bone marrow plasma cells. In other words, they exhibited the same chromosomal aberration as malignant plasma cells. These results suggest a possible origin of CECs from a common precursor of hemangioblasts, which may give rise to both plasma cells and endothelial cells, and indicate a direct influence of CECs derived from MM on tumor angiogenesis and possibly also on disease spread and progression. Yu M et al. demonstrated in their observation that angiogenesis was closely correlated with the prognosis of MM patients. Immunohistochemistry confirmed that high microvessel density could indicate poor prognosis. Assessment of the AAG (angiogenesis-associated genes) signature facilitated the prediction of patient response to immunotherapy and the targeting of more effective immunotherapy strategies [14]. Multiple myeloma remains an incurable disease that poses significant therapeutic challenges. Minnie et al. have already noted in their observations that a breakthrough in myeloma treatment may occur thanks to the emergence of many new immunotherapies [15]. Combining antiangiogenic therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors has become an attractive strategy, although there is still a long way to go, considering the difficulties in controlling the immune system, toxicity, side effects, etc. [16,17]. In our study we also come to conclusions about the significant importance of antiangiogenic medicines.

Conclusions

Patients with higher endothelial cell counts have higher mortality rates. Patients who did not receive antiangiogenic drugs from the start of therapy also had higher mortality rates during long-term follow-up. In everyday practice, the need to use antiangiogenic drugs as part of myeloma therapy should be taken into account. It also appears that in everyday practice, endothelial cell count may be one of many prognostic factors. It appears that patients with high endothelial cell counts should be treated with therapies that also include antiangiogenic drugs. These drugs appear to prolong overall survival in myeloma patients, especially in patients with high endothelial cell counts. Our observations indicate that bone marrow endothelial cell counts may be an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with multiple myeloma. However, our findings require longer follow-up, and perhaps multicenter studies.

References

- P Moreau, J San Miguel, P Sonneveld et al. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017 Jul 1;28(suppl_4). [CrossRef]

- Bruyne E, Menu E, Valckenborgh E et al, Myeloma Cells and Their Interactions With the Bone Marrow Endothelial Cells. Current Immunology Reviews, 2007, 3, 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H. Adair and Jean-Pierre Montani. Angiogenesis. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

- Zhu, Y.X. , Kortuem K.M., Stewart A.K. Molecular mechanism of action of immune-modulatory drugs thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide in multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2013;54:683–687. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. , Leong T., Roche P.C., Fonseca R., Dispenzieri A., Lacy M.Q. Prognostic value of bone marrow angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(8):3111–3116.

- Morgan GJ, Gregory WM, Davies FE et al. The role of maintenance thalidomide therapy in multiple myeloma: MRC Myeloma IX results and meta-analysis. Blood (2012) 119 (1): 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Reyes M, Dudek A, Jahagirdar B, Koodie L, Marker PH, Verfaillie CM. Origin of endothelial progenitors in human postnatal bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:337–346.

- Braunstein M, Özçelik T, Bağişlar S et al. Endothelial progenitor cells display clonal restriction in multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2006 Jun 22;6:161. [CrossRef]

- Matsui W, Huff CA, Wang Q, Malehorn MT, Barber J, Tanhehco Y, Smith BD, Civin CI, Jones RJ. Characterization of clonogenic multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2004;103:2332–2336. [CrossRef]

- Podar K, Anderson KC. The pathophysiologic role of VEGF in hematologic malignancies: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2005;105:1383–1395.

- Kumar S, Witzig TE, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Wellik LE, Fonseca R, Lust JA, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Greipp PR, Rajkumar SV. Effect of thalidomide therapy on bone marrow angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2004;18:624–627.

- Vacca A, Ria R, Semeraro F, Merchionne F, Coluccia M, Boccarelli A, Scavelli C, Nico B, Gernone A, Battelli F, Tabilio A, Guidolin D, Petrucci MT, Ribatti D, Dammacco F. Endothelial cells in the bone marrow of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102:3340–3348.

- Rigolin GM, Fraulini C, Ciccone M, Mauro E, Bugli AM, De Angeli C, Negrini M, Cuneo A, Castoldi G. Neoplastic circulating endothelial cells in multiple myeloma with 13q14 deletion. Blood, 2006; 107, 6, 2531–2535. [CrossRef]

- Yu M, Ming H, Xia M et al. Identification of an angiogenesis-related risk score model for survival prediction and immunosubtype screening in multiple myeloma. Aging (Albany NY). 2024 Feb 5;16(3):2657–2678. [CrossRef]

- Minnie SA, Hill GR. Immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 2020; 130:1565–75. [CrossRef]

- Görgün G, Samur MK, Cowens KB, Paula S, Bianchi G, Anderson JE, White RE, Singh A, Ohguchi H, Suzuki R, Kikuchi S, Harada T, Hideshima T, et al. Lenalidomide Enhances Immune Checkpoint Blockade-Induced Immune Response in Multiple Myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015; 21:4607–18. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, AD. Myeloma: next generation immunotherapy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2019; 2019:266–72.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).